The Two Routes to Anxiety

I

n this chapter we will dive into the anatomy of anxiety. We’ll explain where anxiety originates and how it travels throughout the brain. I’ve tried to make this chapter easy to read but didn’t want to leave out crucial details, so don’t worry if it takes a little while for you grasp some of the processes. Hang on in there. Understanding the brain structures involved can help us to work out how best to manage our anxious thoughts and feelings in social situations.

At the beginning of the second chapter we mentioned that anxiety can originate from two different areas of the brain. Anxiety produced as a result of our thoughts is initiated in the cortex

, and anxiety produced by our reaction to what is happening in our environment is initiated in the amygdala

.

From this point on I’ll refer to anxiety originating in the cortex as the ‘thought route’

and anxiety originating in the amygdala as the ‘reactive route’

. Everyone is capable of experiencing anxiety through both routes, but it’s important to recognise which route the anxiety has originated from in order to effectively manage it.

We’ll now summarise how each of the routes work and how we can best manage the anxiety that originates in each one. I recommend the book Rewire Your Anxious Brain by Catherine

Pittman

if you are interested in reading about the routes in greater detail.

In the personal examples I gave at the beginning of the book, anxiety was aroused in the thought route by my thoughts about how the receptionist at the dental surgery would react to my phone call. The anxiety produced by people looking at me as I walked past the bus stop was a result of my amygdala reacting to the environment – the reactive route. Knowing the differences between the two routes enables us to design practical interventions and exercises that are effective in changing our experience of social anxiety and modifying the circuits in the brain to help us regulate it successfully.

Over the last twenty years, neurological research has revolutionised our knowledge of the brain structures and circuits involved in producing anxiety. Most current treatments for anxiety, such as psychotherapy or Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), are based on changing and disputing thoughts, and therefore target cortex-based anxiety, often only impacting the thought route.

While they can be very effective for managing anxious thoughts, using these exercises when experiencing the reactive amygdala-based anxiety is often ineffectual, and can sometimes be detrimental. Let’s look at the two routes in more detail.

1. The Reactive Route

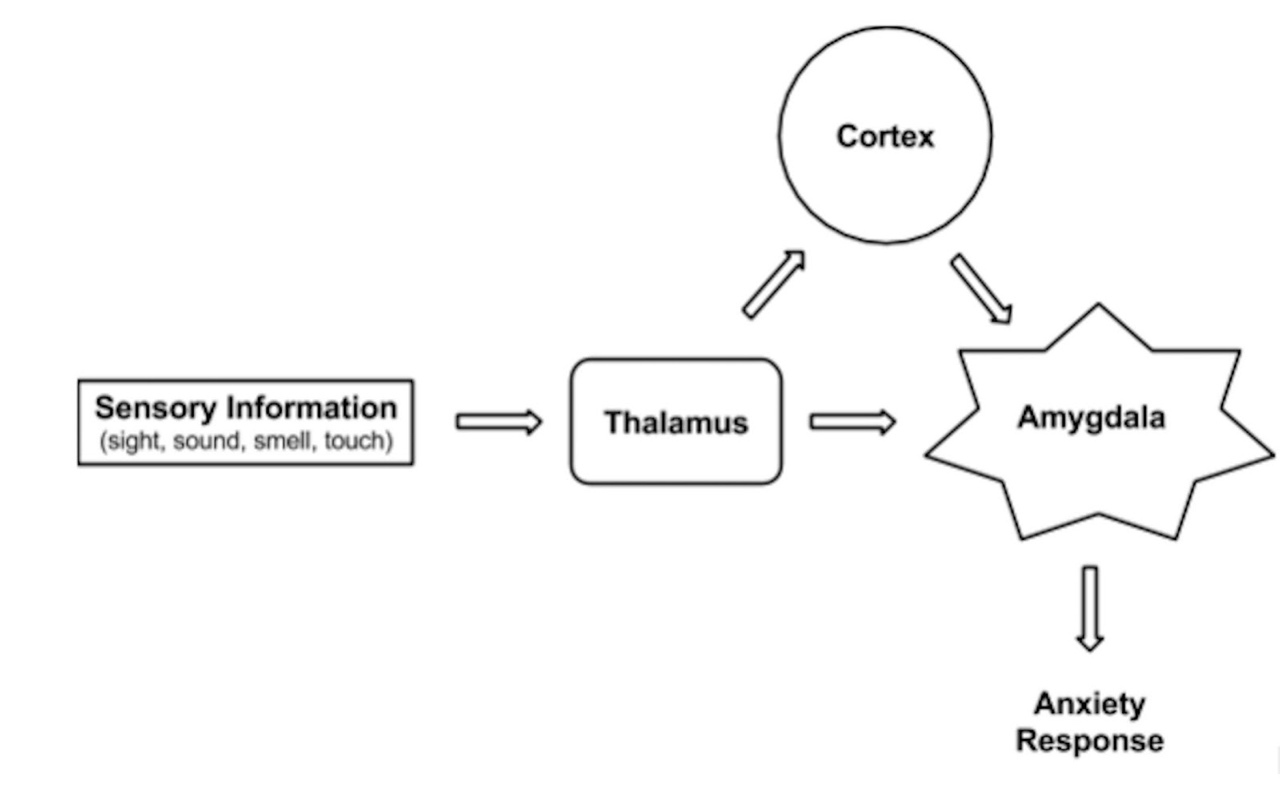

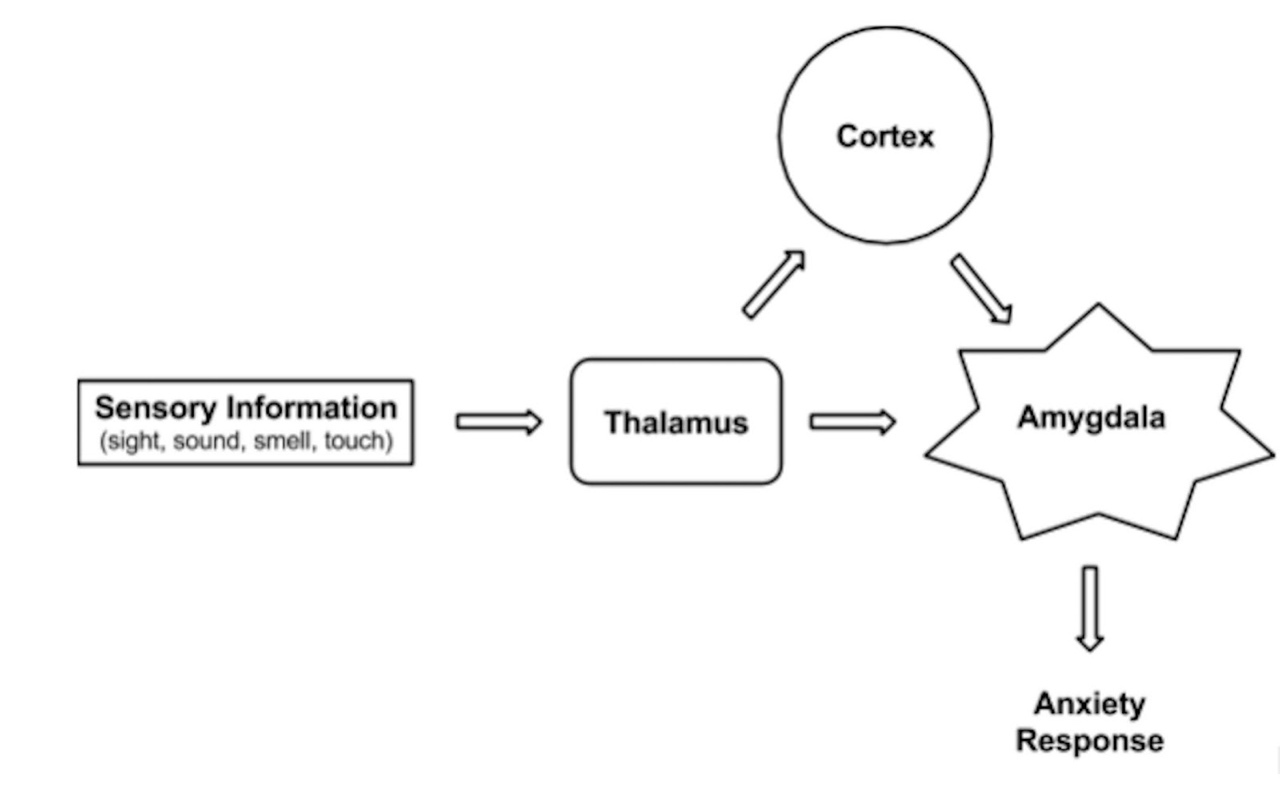

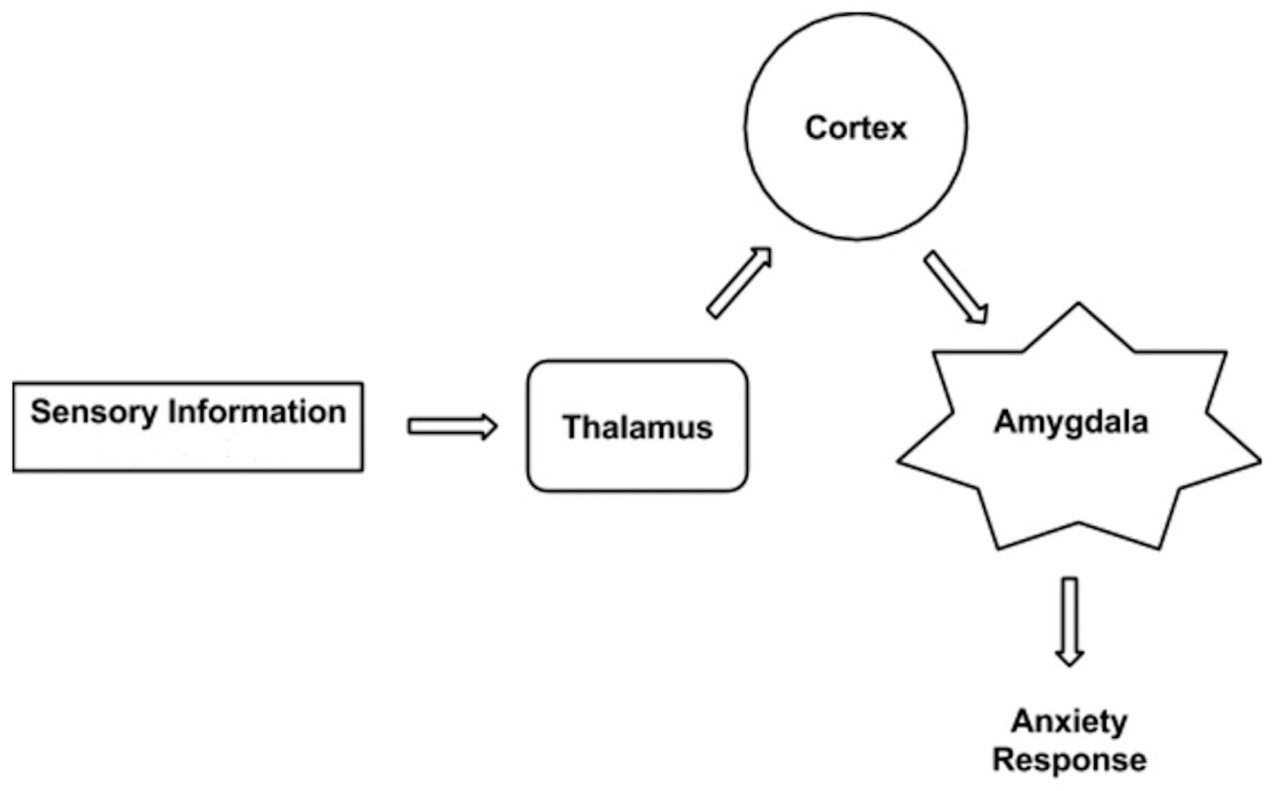

The amygdala is located centrally in the brain and involved in both routes to anxiety. Like a built in security system, it scans the environment for any sign of danger, getting its sensory information (sights, sounds, smells, touch) from another structure in the brain called the thalamus. The thalamus sends the sensory information to both the cortex and the amygdala, but crucially, the amygdala receives this information first (see next diagram).

This is because the amygdala is wired to respond rapidly to save your life; it’s an evolution-based safety measure. If the

amygdala recognises the information received as dangerous, it acts immediately and triggers the emergency arousal system: the fight, flight, or freeze response.

The arousal response energises the sympathetic nervous system, which produces a rapid cascade of physiological arousal, resulting in several changes in the body to ensure we are primed for action. This means your amygdala can react to protect you from danger before your cortex is even aware of what the danger is. This is why we can react by jumping out of the way of a speeding car or rapidly pulling back our hand when it touches a hot surface before we have time to understand what we’re reacting to.

It takes a little more time for the cortex to receive this information and for us to understand what is happening. So we may quickly jump away from a tomato stem that looks like a spider, but then recover almost immediately when the information reaches the cortex, is assessed, and recognised as a harmless tomato stem. For our early ancestors, it was safer for the amygdala to mistake a plant stem for a poisonous spider, than wait for

the cortex to assess the situation before reacting. It could be the difference between life and death.

Being aware of these rapid responses initiated by the reactive route can help us to understand and cope with the symptoms created by the fight, flight, or freeze response, including the most extreme reaction: a panic attack. The amygdala not only reacts faster than the cortex, but there are more connections running from the amygdala to the cortex than the other way around. This enables the amygdala to hijack our thinking, overriding other responses, so there is no logical reasoning, just an automatic reaction.

This is vital when saving our lives (we don’t want to notice the nice tailored jacket of an attacker when he is is running towards us) but it makes it almost impossible for us to reason away this type of anxiety and make sense of why it is happening.

So while cortex-based strategies are more popular, it is essential to also practise strategies that can counter reactive pathway anxiety and train our brain to stop responding unnecessarily in the future.

HOW THE REACTIVE ROUTE LEARNS WHAT IS DANGEROUS

1. Instinct

What sort of information does the amygdala respond to? Research shows we appear to be predisposed to some dangers that have helped us survive and evolve. We tend to react rapidly to snakes, insects, animals, angry faces, and contamination with little hesitation.6

However, with training and experience, even these instinctual fears can be overcome. It’s now common to have animals living with us in our houses as pets, and also for people to handle snakes and spiders without fear.

2

. Emotional Memories

In addition to these predisposed fears, the main way the amygdala learns about what is dangerous is through emotional memories using the process of association. These could be emotional memories you may or may not remember, as the cortex and the amygdala use separate memory systems.

The memory system the amygdala uses doesn’t contain images or verbal information; instead you experience it directly as an emotional state. This is why you sometimes may experience anxiety without knowing why. Maybe a certain smell, location, situation, or object may make you feel anxious for no logical reason that comes to mind. This is the emotional memory of the amygdala at work.

So an object may not be threatening in itself for fear to be associated with it as the amygdala can link it to an emotional memory. If a person was ridiculed by others at a party, while a particular song was playing in the room, just hearing that song in the future may make that person feel anxious, even if they do not recall why.

It can also work the other way, in that a smell, sight, object, or situation may be associated with positive feelings. A loving grandmother may have worn a certain fragrance when handling you as a baby, and now you come to associate that smell with the feeling of love and security, even though you may have no conscious recollection of your grandmother wearing that perfume or even picking you up as baby. So the reactive pathway is responsible for many of our emotional reactions, both positive and negative.

MANAGING REACTIVE ROUTE ANXIETY

The amygdala learns through experience that something is dangerous or upsetting, so using therapies or interventions that target anxious thinking to overcome anxieties caused by the amygdala route aren’t likely to be successful. We’re focusing on

the wrong route. So how do we learn to effectively manage amygdala-based anxiety? There are two main ways.

1. Managing Through Awareness

First of all we must recognise it’s amygdala-based anxiety we’re experiencing and understand that using the cortex to provide logical explanations for this type of anxiety isn’t likely to help, on the contrary it can often make the anxiety worse.

A person attending a large social gathering or party may feel their heart rate rapidly increasing, their breathing becoming shallower, and their hands shaking as they enter a room full of strangers. This is the reactive route at work. What is the amygdala trying to protect this person from? As mentioned earlier, bumping into a group of strangers in prehistoric times was uncommon and dangerous, and there was a good chance we would be robbed, beaten or even murdered. One of the amygdala’s roles is to prevent us from being prey to a predator, and it can often mistake a safe, modern-day environment, for a dangerous one. The anxious reaction may also be the result of an emotional memory of a time when the person had a negative experience in a similar situation in the past.

The person attending the party is unaware the amygdala is automatically reacting to protect them from perceived danger, and in a situation like this, the thought route will use the cortex to create reasons for the anxious reaction, such as ‘I feel this way because I’m worried people will ignore me if I introduce myself

’, ‘ They all seem more competent than me, I’m likely to make a fool of myself if I talk to someone

.’ The more the person focuses on these logical cortex-based explanations for their anxiety, the more anxiety they will create, adding to the original problem. So being aware of the amygdala’s ability to take charge is essential.

If we find ourselves in a situation like this we need to be aware our amygdala is trying to protect us, but what we’re experiencing isn’t life threatening. In the previous example, the party may have

been important, but it was unlikely to mean life or death. So the person must accept the physical reactions were due to the amygdala trying to protect them. While these reactions would be helpful if they needed to fight or flee, this isn’t a dangerous situation, and coming up with logical explanations for it will only add to the anxiety. This is why, when people experience panic attacks, having someone logically explain why they shouldn’t be panicking doesn’t help. They’re talking to a cortex that is switched off or overpowered by the amygdala.

So recognise your amygdala is trying to protect you, but it can often be wrong. You don’t want your thinking to add fire to the flames. We need to recognise when the amygdala is misreading the situation and sounding the alarm for no reason. I’ll explain how we can quieten these thoughts from the cortex and reduce their influence later, in the Three Key Skills: Dealing with Anxious Thoughts and Feelings part of the book. Also, if your reaction isn’t overwhelmingly strong, it’s likely to be a challenge response, and the challenge response can help us to perform better in challenging circumstances. We’ll discuss this in more detail in Chapter 7: The Power of Mindset.

Awareness that the situation is not dangerous and it’s just your amygdala kicking in and raising the alarm won’t always remedy the situation and stop an overwhelming response. However, awareness is a key first step. In some situations, a further successful approach is to use deep breathing techniques or to engage in physical activity; these techniques can engage the parasympathetic nervous system and bring you out of the fight, flight, or freeze response, calming the mind. We go through these and other effective exercises in more detail in the Emergency Exercises: Managing Fight, Flight, or Freeze part of the book.

2. Managing by Learning Through Experience

In order to further reduce or eliminate unhelpful amygdala-based anxiety, you have to use the language of the amygdala rather than

the cortex, and that means learning through experience. If, for example, you want to change the amygdala's anxiety response to talking to a stranger at a party, you must activate the memory circuits that relate to talking to strangers, and only then can new connections be made and the amygdala taught to respond differently. If you want to change the amygdala’s anxiety response to public speaking, you must activate the memory circuits that relate to public speaking.

We mentioned experience-dependent neuroplasticity earlier on in the book, and it is this process that allows the brain to make new connections, alter the circuitry, and change the amygdala’s future responses.

People will, understandably, often try to avoid these challenging and anxiety-inducing situations, but avoiding them stops the amygdala from forming new connections and responding differently. The amygdala tries to preserve learned emotional reactions by avoiding exposure to the triggers. This decreases the likelihood of any neural changes or the anxiety being eliminated. By exposing ourselves to situations or objects that make us anxious, but challenging that association – by realising nothing bad happens – we can develop new connections in the amygdala that compete with and eventually overpower those that create fear and anxiety.

If we can see anxiety-inducing situations as an opportunity to learn, change, and rewire our neural pathways, we can motivate ourselves to confront them. Although difficult, if we nurture an opportunity mindset, and understand that exposing ourselves to the anxiety that arises will produce positive neuroplastic changes, we can grasp the courage to face our fears and become unstuck. We’ll address how to take action despite feeling anxiety and fear in Part 4: Action Mode: A Step-By-Step Social Anxiety Action Plan

.

2. The Thought Route

When we think of anxiety, we normally associate it with cortex-based anxiety, the type of anxiety created by anxious thinking. We’re more consciously aware of this type of anxiety and can recognise it in our thoughts and feelings. This is because the cortex is more directly under our control than the amygdala. As a result, we’re able to train ourselves to be aware of, interrupt, and change anxious thoughts and images, and therefore reduce our anxiety. However, this isn’t always easy, as we develop longstanding patterns of thinking and ingrained habits.

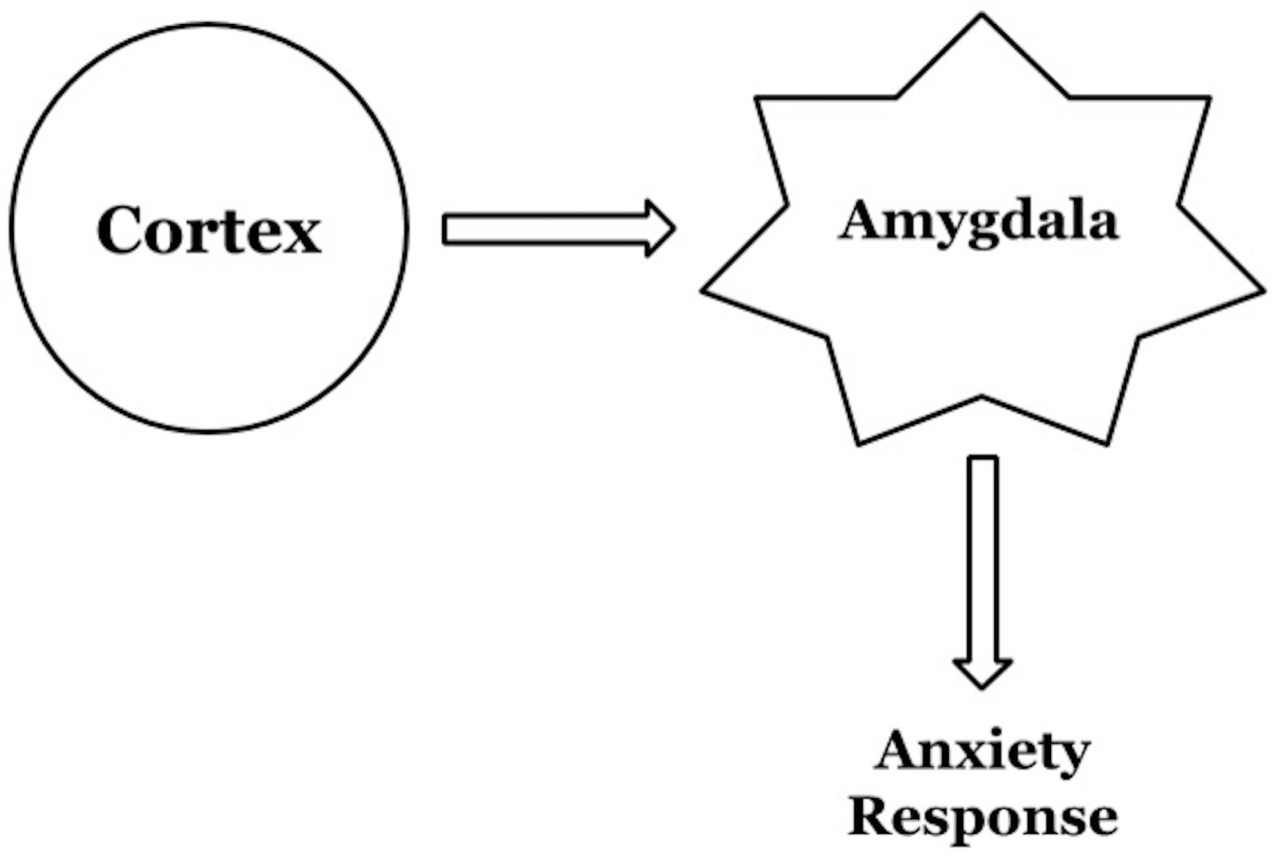

The cortex can influence our anxiety in two main ways. Firstly, as described earlier, it can worsen anxiety in the amygdala by creating unhelpful and inaccurate reasons for our anxious feelings, and secondly, it can independently initiate unnecessary anxiety using thoughts and images.

HOW THE CORTEX INITIATES ANXIETY

The cortex can initiate unnecessary anxiety using thoughts and images in two main ways.

Firstly, by interpreting neutral or harmless sensory information (sights, sounds, smells, touch) provided to it by the thalamus as threatening, and then sending this information onto the amygdala to produce anxiety.

For example, you’re walking through a restaurant when you notice someone look up at you, smirk, and shake their head. You immediately wonder why they don’t like you, what they find so amusing, and why they’re being so dismissive of you. You get closer to the person and realise that they’re in deep conversation on their phone and not aware of you at all.

The second way the cortex initiates anxiety using thoughts and images is by independently producing it’s own distressing thoughts, without receiving sensory information.

You’re due to deliver a presentation at work in a few days time and while lying in bed you imagine that you’ll forget some of your main points and panic in front of everyone. Your cortex sends this information onto your amygdala and an anxiety response is triggered, even though there has been no sensory information provided about your presentation.

The amygdala responds to imaginary information in the same way it responds to a real situation, so anxiety brought about by thoughts and images created in the cortex is just as strong as the anxiety you will experience from a real situation or threat.

We often worry in this way, hoping the rumination will lead to a solution or will help to guard us against future negative

events. We can sometimes come up with novel solutions through worrying, but rarely do. More often than not we strengthen the neural pathways in the cortex that create worry. Due to neuroplasticity, whatever you devote a lot of time to thinking about in great detail is more likely to be strengthened, creating a vicious circle.

MANAGING THOUGHT ROUTE ANXIETY

There are a number of key skills we can learn to help us effectively manage anxious thinking. Remember, in the thought route, the cortex initiates anxiety in one of two ways; by interpreting neutral sensory information as dangerous, and sending this information to the amygdala to produce anxiety; or by creating anxious thoughts and feelings on it’s own, without sensory information, and again, sending this information to the amygdala to produce anxiety.

So we need to learn to manage unhelpful thoughts and images in a way that will eliminate the anxiety response of the amygdala or reduce its strength. This will enable us to take control of our behaviour and engage fully with our actions, rather than entering safety mode and allowing our anxiety to lead the way.

Before we outline these keys skills, let’s investigate some of the other, more common solutions we are told can help reduce negative thoughts. The advice often tells us to:

-

Challenge or dispute the thoughts by looking for evidence to demonstrate that they aren’t true.

-

Replace negative thoughts with positive thoughts.

-

Distract ourselves from these thoughts.

You may have tried one or more of these strategies before, and if so, you may have recognised some common problems with these approaches:

-

They require a lot of effort and energy and can divert you from your original intention.

-

They focus your mind on the negative thoughts.

-

They only tend to give you temporary relief before your mind comes up with new negative thoughts.

-

When you leave your comfort zone to enter a challenging situation they don’t work.

If these methods don’t work as long-term strategies, what’s the alternative? Well, there’s a radically different way of responding to negative thoughts that may seem counterintuitive.

The approach comes from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (often abbreviated to ACT) — an evidenced-based psychological intervention that uses acceptance and mindfulness strategies to overcome anxiety and manage stress.7

ACT suggests we can reduce the influence of negative thoughts and anxious feelings without trying to get rid of them. This method works even though it makes no effort to reduce, challenge, eliminate, or change negative thoughts. Why? Because it starts from the assumption that negative thoughts are not inherently problematic.

In his book, The Happiness Trap

, leading ACT practitioner Dr Russ Harris, explains that negative thoughts are only considered problematic if we get caught up in them, give them all of our attention, treat them as the absolute truth, allow them to control us, or get in a fight with them. You may remember from earlier that when we get caught up in our thoughts, give them all of our attention, and consider them to be the absolute truth, we’re considered to be FUSING with them. When two things fuse they become joined together as one. When we’re caught up in our thoughts in this way we are cut off or disconnected from what is happening right in front of us, and this makes it difficult to engage with our environment. Our anxious thoughts become our reality and dominate our behaviour.

The ACT approach teaches three key skills to help us effectively manage cortex-based anxiety: defusion

, expansion

, and

engagement

. We’ll briefly outline these skills next and go back to them later on in the book to explain how we can apply them.

1. Defusion

To counteract unhelpful thoughts, we can defuse, or separate, from them. When we defuse from thoughts we become aware they are nothing more or less than words and pictures, and can have little or no effect on us, even if they are true.

As an analogy, imagine you’re driving a bus, while all the passengers (thoughts) are noisily chattering, being critical, or shouting out directions. You can allow them to shout, but choose not to engage with them, keeping your attention focused on the road ahead. If you turn around and argue with the passengers, you may have to stop the bus, or become distracted and make a wrong turn. So you keep driving, allowing them to shout, but safe in the knowledge they can’t hurt you. You defuse from them.

2. Expansion

When our cortex provides us with unhelpful thoughts we will often experience uncomfortable feelings as a result. As mentioned earlier, we normally do our best to avoid these feelings or sensations, we try to distract ourselves from them, or get rid of them. However, we can learn to deal with them effectively by using expansion – this is the ability to open up and make room for emotions, sensations, and feelings.

So we accept they are there, and allow them to pass through without impacting our behaviour. When we experience anxious feelings, we don’t battle with them, but we accommodate them and allow them to come and go in their own time. It doesn’t mean we want them, like them, or approve of them, but we stop investing our time and effort in fighting them. The more space we can give the difficult feelings, the smaller their influence and impact on our lives

.

3. Engagement

The next step is engaging with experiences, tasks, and situations, despite unhelpful thoughts and uncomfortable feelings. Engagement is being present and actively involved in what we are doing – not lost in our thoughts. Being anxious is not a problem, but disengaging from our experience is.

The more we focus on unhelpful thoughts and unpleasant feelings, the more we disconnect from the present moment. This particularly tends to happen with social anxiety; we get hooked on stories about the future, about how things might go wrong, and how badly we will handle them. We don’t have to be connected to the present moment all the time, but it is particularly useful to do so in a number of situations, particularly when anxiety is diverting us away from our desired behaviour.

We will get into the detail and practicalities of defusion, expansion, and engagement in Three Key Skills: Dealing with Anxious Thoughts and Feelings

, and also go through a number of different of exercises to see what works best for you.

So far we’ve discussed how and why anxiety develops, described the routes it takes, and outlined how we can start to manage our anxiety. Before starting the practical journey and beginning the exercises, we’re first going to raise awareness of how anxiety can progress in a way that seriously impacts our lives. Shining a light on how anxiety can become a disorder can help to take us out of automatic pilot and stop our anxiety in its tracks before it becomes a major problem.