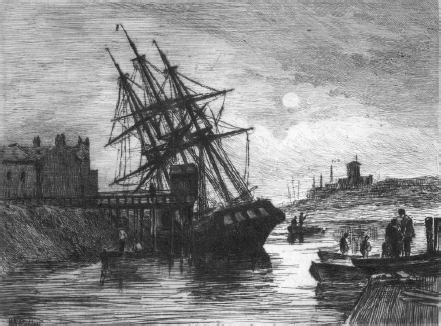

Bristol Harbour in decline, 1890. A collier stranded at low tide. Bristol Cathedral is on the hill to the right.

The coal miners built what we know as modern Britain – it was the coal-fired engines that fired the factories, fired the trains that took the goods around the country and to the ports, coal-fired ships that took our goods abroad, protected by coal-fired naval warships. So, if you object to coal-mining, you are really saying that we should have remained a little island off the north-west coast of Europe – a romantic idea. That’s what would have happened.

Tony Benn, Cornerstone magazine, Summer 2010

Unusually for him, Tony Benn was spot on. Britain’s great leaps forward were largely funded by two things: wool in the Middle Ages and the coal beneath our feet. Wool may not be so important these days, but coal is still the second-biggest source of energy in the country.

Coal is formed by long-compressed mud, jungles, dead ferns and mosses. And it just so happens that the Midlands and the north of England – like Wales – are particularly rich in that long-compressed vegetation. So the titanic industrial efforts used to extract coal from the ground – and the associated iron- and steel-making plants, and metal-bashing factories – were concentrated in the Midlands and the north.

The north–south divide – and all related ee bah gum, it’s grim up north material – was born; or, to put it more accurately, was widened. A north–south divide existed long before the first great coal mines were dug.

In the Canterbury Cathedral archives lies the 1072 Winchester Accord, signed with the mark of the illiterate William the Conqueror in the chapel of Winchester Castle. William agreed in the document that the southern province of Canterbury should take precedence over York, which had once been the capital of the Roman province of Britannia. After his savage northern campaign in 1069–70 – the Harrying of the North – he appreciated that there was a real division between the rebellious north and the more easily pacified south.

You can still see the effects of William the Conqueror’s campaign, and the divide between north and south, in medieval settlements in County Durham, planned by Norman hands in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

Norman control was imposed from above by the dirigiste construction of new villages, built on one of three different plans: two rows of buildings, often farmhouses, facing each other across a green or street; four rows of buildings ranged around a square; or single farms. The four-row developments were set up by chartered boroughs; the two-row ones by medieval villeins. Bishop Auckland and Darlington have examples of both two-row and four-row settlements.1

This was settlement by invader’s decree, as opposed to the usual, natural, organic growth of English villages. County Durham also faced border raids from Scotland; which might explain the number of villages with big greens protected by encircling settlements, like Easington, Trimdon, Hett, Hamsterley and Heighington.2

Even if it has been almost a thousand years since England was successfully invaded, war, and the fear of border invasion, has helped dictate England’s look ever since, right up until the Second World War. In 1940, 18,000 pillboxes were built after Dunkirk, and many still survive: of the 300 built for the Taunton Stop Line, a mini-Maginot line running from Seaton, Devon, to just north of Bridgwater, Somerset, two thirds remain. The Taunton Stop Line, designed to stop German armoured fighting vehicles invading from the west, was one of fifty Second World War defensive lines across the country.

Because the English are now on good terms with France, as well as Scotland and Wales, it’s hard to think of England’s northern and southern borders as either hostile or defensive. But that’s what they were for centuries – like the India–Pakistan border is today – and border counties still bear the marks of those days.

Nikolaus Pevsner called Northumberland ‘the castle county of England’, with its 500 castles, buildings and defensive pele towers (also found in the borderland of Cumbria).3 In a similar way, Kent’s identity was forged by being the closest county to the Continent. As frontier territory, it needed a military presence early on; in the second century AD, the Romans’ Classis Britannica – the British Fleet – was based at Lympne and Dover.

Kent’s closeness to the Continent meant that, when Pope Gregory sent St Augustine to England in AD 597, Canterbury was his principal outpost; it remains the centre of English Christianity. There are still remains of ten seventh-century churches built by Augustine or his converts in Kent; with another in Bradwell, Essex. Kent benefited, too, from the waves of Norman and Gothic architecture that flooded in from France after the Conquest.

The county’s nearness to France led to the import of French building materials – particularly the excellent Caen oolitic limestone from Normandy – by the Normans, through the Middle Ages, and on into the Victorian age. This expensive stone is often used as trimming on window frames, doorways, gargoyles, pinnacles and finials. Bell Harry tower, the central tower of Canterbury Cathedral, has a core of half a million bricks wrapped in Caen stone.

Today, there are more castles in Kent than any other southern county. Rochester Castle has the highest keep in England. In Essex, another international border county, the biggest keep in Europe is at Colchester Castle, built in the late eleventh century on the Roman foundations of the Emperor Claudius’s first-century temple.

The Welsh border was also defensive for centuries. Herefordshire has a chain of castles running through the county, continuing into Monmouthshire to the south, and Shropshire to the north, where the medieval frontier architecture is similar to that of the northern borderlands. Church towers on the Welsh borders have such thick walls that they were probably also military refuges. The church at Ewyas Harold, Herefordshire, has 7ft-thick walls, and Monnington-on-Wye Church, also in Herefordshire, has battlements and cross-shaped arrow-slits.

For all the talk about England being full of castles, plenty of counties don’t have many of them. Hampshire, a coastline border county like Kent, needed fewer castles, because it was naturally protected by its thick woods; and its chalk uplands were underpopulated and relatively poor.

Castles thrive where battles are threatened. Somewhere like Oxfordshire may be in the heart of England, but it was never the country’s military cockpit; so the county is light on Norman castles. After the Conquest, the Thames was defended further east, on the banks at Windsor and Wallingford, in Berkshire, and, further afield, at Buckingham, Canterbury, Winchester and Cambridge.

Norfolk has no Norman castles, apart from Norwich, because the county had little tactical advantage, moored as it is on the north-eastern edge of East Anglia. Bedfordshire has no castles at all, except for Norman motte and baileys. These were the simple early-Norman castles – with a motte (a giant artificial earth mound with a wooden tower) next to a bailey (an enclosure formed by steep banks and ditches). It’s a safe bet that any surviving motte dates to within a century of 1066.

Southern border counties were even more heavily fortified in the early nineteenth century, as fears of a Napoleonic invasion grew. In 1806, the Martello towers at Folkestone, Dymchurch, went up; Fort Clarence, Rochester, was built in 1812. The Western Heights at Dover – which could accommodate 4,000 soldiers, buried within the hillside – were built in 1814.

Another chain of southern forts – Palmerston forts – was thrown up around Portsmouth in 1859, with the renewed threat of French invasion. Further forts were built around the British coast through the 1860s, from the Bristol Channel to Chatham, from Plymouth to Sunderland.

Throughout the medieval period, the divide between north and south persisted. Fertile southern areas that were rich then remain rich today. In 1334, Berkshire and Oxfordshire, then worth £20 per square mile, were two of the richest counties in England, as they still are. In the 2001 census, a third of households in Oxfordshire had three cars or more; Oxford had the third-highest proportion of professionals in England and Wales, 23.4 per cent of the employed population.

Until the Industrial Revolution, the south was much more heavily populated than the north, and more generally in the swing of things – even in the late seventeenth century, only a quarter of the English population lived north-west of the line from Boston, Lincolnshire, to Gloucester.

Before the modern age, the north was considered remote, colder, on the way to the Arctic. To the south lay Europe – or pretty much the rest of the world, as we then knew it, until the discovery of America in the late fifteenth century and the expansion of trade links with the east in the sixteenth century.

A reverse pattern existed – and exists – in Italy, where the more temperate north looks down on the intense heat, supposed laziness and fecklessness of those in the Mezzogiorno, down in the barbarous south. Both England and Italy consider themselves more civilized the further they get from harsh weather.

It is in the south that the Cinque Ports were set up by Royal Charter in 1155, for trade and defence. Two of them, Sandwich and Hythe, have particularly grand churches as a result. Medieval prosperity is still apparent in Kent: there are more monumental brasses in Kent churches than in any other county; Cobham, with sixteen brasses, has more than any other English church.

The shape of England, with pretty much a linear outline heading north–south, leads neatly to north–south splits; as it does in Italy, also built along a rough north–south spine. Countries aligned along an east–west axis, like America, are more likely to define themselves by those compass points.

Admittedly, there are strong east–west splits, too, along the length of England. Rivers naturally flow to east or west from the country’s central spine. In the Midlands, the Arrow, Alne and Avon rivers drain west into the Bristol Channel and the Atlantic; the Cole, Blythe and Anker rivers head east to the North Sea, via the Humber and the Trent.

Coal deposits aren’t restricted to the Midlands and the north, either. Coal is found in Kent and the south-west, particularly in Somerset.

But it’s that much harder to get the stuff out of the ground in the West Country. When south-west England was twisted and crushed 250 million years ago by the geological phenomenon known as the Hercynian orogeny, the Somerset coal seams were flipped on their head, at hard-to-get-at distorted angles; certainly much harder to get at than the seams in the Midlands and the north.

Rural Somerset might well look like the industrial north today if its coal had been easier to extract; County Durham was all high moors and rolling hills until coal was discovered and industry invaded the landscape.

And Devon and Cornwall might have looked like Sheffield if they’d found coal there, not tin. Disused West Country tin mines don’t spoil the modern landscape; with their derelict chimneys and engine houses for hauling up water and waste rock, they even add a maudlin, faded grandeur to the scene.

The heaps of spoil left by early ‘streaming’ tin-miners, who picked ore from streams, were relatively small. Later tin-miners cut tunnels and sank shafts into hillsides, particularly in Cornwall and on Dartmoor. But time has softened these minor scars, and the landscape has if anything gained drama from this minor surgery.

Copper mining in Cornwall, which peaked between 1700 and 1870, didn’t destroy the landscape, either, not least because the ore was shipped to Swansea for the messy process of smelting, and south Wales took the aesthetic hit instead.

Industrial effects on the landscape can occasionally be enormous outside the north. The china clay mines in Cornwall produced a new geological layer of mining spoil, moulded into streaky brown and white moonscapes. In St Austell, mining for kaolin, a type of aluminium silicate, formed its own set of mini-Alps from the spoil. Excavation also produced its own distinctive landscape: the Eden Project in Cornwall is built in a disused china-clay pit.

There are industrial remnants left, too, in the supposedly pampered urban south. The old workers’ leisure club from the Huntley and Palmer biscuit factory still survives in Reading, once known as Biscuit Town (with Reading FC known as the Biscuit Men, and Reading Prison as the Biscuit Factory). The art deco Hoover Factory on Western Avenue, Perivale, Middlesex, built in 1935, is now a supermarket.

The large-scale effects of the Industrial Revolution may have dodged much of the south – there was never much heavy industry going on in, say, Thomas Hardy’s Dorset. But that’s not to say that southern, and western, counties didn’t have their great industries, too. It’s just that those industries were either cleaner, or belonged to an earlier age, when the effect on the landscape was on a smaller scale.

Or, indeed, to a later age, when technological advances restricted the effect on the landscape. When the first black-and-white, live satellite television pictures from America arrived here in 1962, there had to be a receiving dish to catch them. That relatively unobtrusive dish was at Goonhilly Downs Earth Station, on the Lizard, Cornwall; as close as possible to America. The Lizard – at Poldhu – was also where Marconi did his first radio experiments in 1901.

These modern innovations, carried through the air, or along cables on the seabed, don’t disturb the landscape the way large-scale mining did.

Britain’s modern oil industry, too, leaves barely a mark on the landscape. In January 2011, 6 million barrels of crude oil were discovered beneath the thatched cottages, rolling fields and ancient coppiced woodland of the West Sussex hills. Walking around the picture postcard hamlet of Forestside, on the edge of the South Downs, by the Hampshire border, there’s not much to show that you’re in the Klondike of south-east England.

Horses and sheep graze the fields round the drilling site in Markwells Wood. All you can hear is a birdscarer, the occasional pheasant flushed from the undergrowth, and the odd bang from a nearby shoot.

In a clearing in the hanging woods, fringed with bracken and silver birch and beech trees, invisible from all directions, is a flat, square patch of gravel.

About the size of three tennis courts, this gravel patch, bordered by a 6ft-high mesh fence, juts out over the edge of the hill. In the middle of that gravel is a 12 by 12 feet concrete platform, with a bright-red stopper at its centre, like a giant New York fire hydrant. Hundreds of millions of gallons of oil come gushing through this tiny little puncture in the earth’s surface.

Pre-drilling surveys revealed that the oil was trapped in a fault in the Great Oolite stone stratum below; a fault running east–west across the county – the reason they’ve been striking oil in this corner of England since 1980.

There are ten oilfields in the Weald basin, with the oilfields running into East Sussex, in Storrington, and all the way to neighbouring Surrey, at Bletchingley, by the M25. Further north, in Berkshire, in 1994, the Queen gave permission for exploratory drilling in the grounds of Windsor Castle.

The offshore oilfields in the North Sea are well-known. Our onshore sites aren’t so familiar but, in fact, prospectors have been finding oil under British soil since 1945. There’s oil, too, in Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Lincolnshire and Yorkshire, although, admittedly, in small amounts: the only large onshore site in Britain is at Wytch Farm, Poole, Dorset, the biggest onshore oilfield in Western Europe.

Once the oil is drawn from over a mile beneath the earth’s crust at Forestside, the well will be capped, and the patch of gravel returned to woodland. The only manmade structures on the horizon will again be the ancient houses of Forestside: with distinctly unindustrial names like Glebe View Cottage, the Willows and Virginia Cottage.

The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century iron industry in the neighbouring East Sussex Weald left a much deeper mark on the countryside than modern oil exploration ever will. The county is still scattered with old hammerponds, formed by dams that powered hammers for crushing iron ore. The surrounding forests supplied the timber, burnt for smelting the metal from the local ironstone.

If the modern oil industry leaves the land almost untouched, the non-mineral industries of the Industrial Revolution often enhance the look of a place. In genteel Bradford on Avon, Wiltshire, you can still see the fetching water- and steam-powered mills – there were thirty of them in the town – which became defunct in the late nineteenth century when the wool industry migrated to Yorkshire.

The Cotswolds were once an industrial heartland, also devoted to wool production. Cotswold is thought to mean ‘sheep enclosure in the rolling hillsides’; sheep were so valuable there in the Middle Ages that they were known as the Cotswold Lion. Old mills survive in Wotton-under-Edge and Painswick. There are still signs of industry around the rivers, required for fulling (or washing) wool, particularly in the Little Avon, Ewelme and Frome valleys. These date from the days before steam power replaced water power, allowing cotton and wool mills to leave the river valleys. The local towns – Tetbury, Cirencester and Stroud – and their churches expanded on the back of the wool industry.

As late as 1801, the fabric towns of the Cotswolds – Witney, with its blankets; Chipping Campden, with its silk and wool – were some of the most heavily populated in England. Fewer people live in the Cotswolds now than in the Middle Ages.

The industry’s effects on the landscape, though, are that much less than in the north because its source materials – sheep and grass – were agricultural, not mineral. You didn’t need to gouge into the landscape and there was barely any spoil to deal with.

Leicestershire’s industry also grew out of sheep-farming. In 1724, Daniel Defoe wrote, ‘The whole county seems to be taken up in country business. The largest sheep and horses are found here, and hence it comes to pass, too, that they are in consequence a vast magasine of wool for the rest of the nation.’

Because of all that wool money, there are plenty of large fourteenth- and fifteenth-century churches in Leicestershire. The trade also led to the growth of wool-combing and spinning in the county in the fifteenth century; and in turn to the hosiery industry moving there from London in the seventeenth century.

Plenty of light was needed, and so extra windows were put into hosiery workers’ cottages – you can still see the long, top-floor windows on the houses in the village of Shepshed. The textile industry expanded in Leicestershire well into the nineteenth century, with large steam-powered mills built in Leicester, Loughborough and Hinckley.

Alongside Leicester’s canal, heartland of the city’s industry, the old dyeing factories survive, fitted with louvred roofs to let the fumes disperse. Industry was boosted by cheap coal transport along the River Soar, made navigable as far as Leicester in 1794, and Loughborough in 1777.

Fumes from those dyeing factories apart, Leicester’s industries were relatively clean and small-scale – meaning the city wasn’t transformed to the degree that northern cities were by the Industrial Revolution.

The grim clichés of northern life are deepened by the wildness of northern landscapes.

Wuthering Heights can only wuther – the word means ‘howl’ or ‘eddy’ – if there are some moors for the wind to go wuthering through. Heathcliff’s gritstone moors of Yorkshire are open, bare land with black hollows and crags, where the wind and rain can wuther away to their hearts’ content.

Bleak, wuthering weather depends on being high on the hills. Dip down from the moors, head east of Knaresborough, and you hit the rolling, wooded farming country of the Vale of York, west of the Jurassic hills made of sandstone and limestone. The vale lies on a flat bed of Magnesian limestone – known also as Redlands limestone, it’s responsible for the fertile, red soil of the area. It’s also wonderful building stone – used to build Ripon and York Minsters. All around is rich agricultural land supporting prosperous farmers, chocolate box villages and picturesque market towns.

The landscape is far from uniform in the industrial areas of the north. In the West Riding of Yorkshire, the steel and coal works in Sheffield and Rotherham may have scarred the land; but the wool and worsted mills around Bradford, Halifax and Huddersfield laid down a handsome, robust, architectural relief over the natural beauty of the country.

Whether for good or ill effect, the greater scale of the industries of the Midlands and the north altered the lie of the land that much more deeply than southern industries. The changes were so deep that echoes survive of the first industrial landscapes of the 1760s and 1770s – particularly in the ironworks at Coalbrookdale, Shropshire, Richard Arkwright’s spinning mill in Nottingham, and Josiah Wedgwood’s factory at Etruria in the Potteries.

Victorian social division can still be spotted today in the layout of industrial towns and cities. In these hilly northern areas, it was easier to build on the flat valley floor. But living in the depths of the valley, where water gathered and natural drainage was bad, wasn’t healthy. Manufacturing tycoons gravitated to mansions on top of the hill; working-class housing was consigned to the valley floor. The word slum, first used at the height of the residential building boom in the 1820s, is derived from the Low German slam, meaning mire.

The population expansion brought by industry was staggering. London may have grown sixfold from 1800 to 1900, but that was nothing compared to the growth of the northern industrial cities. Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool and Sheffield, once small medieval towns, became colossal cities on the back of unprecedented volumes of trade and manufacture.

There had been coal-mining and weaving in Lancashire since the thirteenth century; by 1375, Edward III had set up a colony of Flemish weavers in Manchester. Cotton was imported to Lancashire from Cyprus and Smyrna as early as 1600.

But the industrial identity of the north, and the deepening of the north–south divide, only really set in during the late eighteenth century, when the weaving of cloth from cotton began in Lancashire, helped by the 1774 reduction of tax on cotton goods from 6d to 3d a yard.

A quick succession of revolutionary inventions intensified the northern wool industry: John Kay’s fly-shuttle in 1733, followed by Hargreaves’s spinning jenny in 1765, Arkwright’s water-frame and Crompton’s mule in 1780, and Boulton and Watt’s steam engine in 1787.

The effect on the look of the north was immediate, and on an unprecedented scale.

Before cotton-spinning arrived in Preston in 1777, it was a small Lancashire town of 6,000. By 1877, once industry had got a foothold, its population was 90,000.

In 1829, Middlesbrough was a hamlet of forty people, centred around a single farmhouse on the River Tees. The 1845 extension of the Stockton to Darlington railway to Middlesbrough singled it out for expansion (on a carefully planned grid, incidentally). The fastest-growing town in British history, Middlesbrough was nicknamed the ‘Infant Hercules’ by Gladstone. The first blast furnace was built in 1851; in 1875, the first steel plant opened. By 1901, once iron ore was discovered in the neighbouring Eston Hills, 90,000 workers lived in ‘Ironopolis’.

Wordsworth described the effect:

Meanwhile, at social industry’s command,

How quick, how vast an increase!

From the germ

Of some poor hamlet, rapidly produced

Here a huge town, continuous and compact,

Hiding the face of earth for leagues.

The Excursion (1814)

The power of industry was so great that, while Middlesbrough grew at a lightning rate, non-industrial cities nearby were barely changed. Durham’s population in 2001 (29,091) was barely bigger than in 1900 (20,000), and not much more than in 1840 (17,000).

Birmingham began life as an Anglo-Saxon hamlet, named after the Anglo-Saxon Beorma tribe who settled there. Built on poor soil at an awkward splitting point in the River Rea, it first expanded because it was a handy meeting point for farmers from nearby richer villages.

Between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries, Birmingham grew from a small Midlands town into one of the world’s leading centres of manufacture, the ‘city of a thousand trades’. Now, it’s the second-biggest city in Britain, with a population of 977,087 in 2001. You can diagnose the late date of the city’s development by its lack of medieval churches; particularly when compared to medieval metropolises such as York or the City of London.

Birmingham is neither on the sea nor on a navigable river, but it did have two minor advantages. It got its market charter in 1166, but was never incorporated as a borough. That meant it was open to outside labourers and craftsmen, but had none of the constraints on trade imposed by a traditional burgess system.

The city was also an early industrial centre, if a small one. In the Middle Ages, Birmingham was one of a handful of Black Country villages at the centre of iron and coal production. It helped, too, that the city was on the south-eastern edge of these villages – and so closer to London.

Early in its history, Birmingham had established itself as a place for metal manufacture, helped by plenty of streams and water mills. A Birmingham goldsmith is recorded in 1406. By 1643, Prince Rupert, Charles I’s commander in the Civil War, sacked Birmingham because its gunmakers were supplying Parliament’s armies.

You can see this process – of medieval, small-scale industry leading to exponential development and diversification – in Sheffield, where cutlery was made as early as 1540, when the antiquary John Leland wrote of ‘many Smiths and Cuttelars in Hallamshire [the parishes of Bradfield, Ecclesfield and Sheffield]’.

The same went for Coventry – which made cutlery in the thirteenth century, cloth in the fourteenth century, gloves in the fifteenth century, buttons in the sixteenth century, clocks in the seventeenth century and ribbons in the eighteenth century. Weavers’ houses still survive in the city, their close-set second-floor windows positioned in front of the looms.

Coventry’s diversification didn’t stop there. It moved from ribbons in the early nineteenth century, via watch-making and sewing machine manufacture, into bicycle-making in the 1870s, and then on to cars; William Morris’s Oxford factory made the same jump from bicycles, via motorbikes, to cars in 1913, with the manufacture of the first Morris Oxford. Coventry’s Daimler factory was built in 1896, laying the foundations for the city’s long car-making history.

Back in Birmingham, the metal industry diversified from metal toys, trinkets and boxes, into electroplating – invented by Elkington’s of Newhall Street – along with diamond trading and case-making in the Jewellery Quarter. Small-scale manufacture in Birmingham’s houses-cum-workshops flourished from 1830 until 1880. In the early twentieth century, bigger T-plan factories were built, with long workshops stretching at right angles to the front office, casting as much light as possible on to the factory floor.

The expansion of Birmingham and the diversification of its industries were accelerated by the railways. The London and Birmingham Railway, opened in 1837, was the first main line in Britain. As a result, Birmingham’s population grew from 86,000 in 1801 to 147,000 in 1831, and 233,000 in 1851.

As industry increased and diversified, those workers had to be housed. Birmingham’s twentieth-century municipal housing programme – 50,000 houses built in 1939, mostly plain brick cottages in pairs and rows – was the biggest in England.

Looking at these vast population movements, it seems odd that our Industrial Revolution was smaller than that of many of our Continental neighbours, even if it was the first.

We were the first in so many ways – the first to develop the industrial architecture of the iron bridge, the first to pioneer dock warehouses on a grand scale, the first to use ornamental cast iron so widely. A lot of it is still visible in the iron railings in front of so many terraced houses; some of those railings have remained black ever since they were repainted in 1861 to mourn Prince Albert.

To begin with, Europeans were staggered by the size of British industry. The Prussian architect, Karl Friedrich Schinkel, said of Manchester in 1826, ‘400 large new factories for cotton-spinning have been built, several of them the size of the Royal Palace in Berlin, and thousands of smoking obelisks of the steam engines 80 to 180 feet high destroy all impression of church steeples.’4

Still, we never had the really enormous factories on the scale of those built in the later nineteenth century, and the twentieth century, in Germany and Russia; the factories that helped foster the mass labour movements which became fertile breeding grounds for Communism.

We were, though, extremely competitive when it came to the scale of the industrial recession that so deepened the north–south divide in the late twentieth century. Cities, so quickly pumped up by the industrial boom, deflated just as dramatically when recession hit.

The 1980s recession is the one that sticks in our minds; the one that has had the most powerful psychological effect on the north–south divide.

But there were earlier recessions. In 1675, Bristol was the second city of Britain, having accelerated ahead of its medieval rivals, Norwich and York. Its maritime trade was hampered, though, by the River Severn’s vast tidal range, which made it tricky for ships to reach Bristol’s port. They sometimes waited for a month for a strong enough wind to carry them up the Avon.5 When transatlantic steamships arrived in the mid-nineteenth century, Bristol was just too far from the ocean; and Liverpool increasingly took over its sea traffic.

Bristol Harbour in decline, 1890. A collier stranded at low tide. Bristol Cathedral is on the hill to the right.

Things got worse for Bristol with the end of the slave trade in 1807; a noble moment in British history, certainly, but it didn’t do much good for the balance sheet of Bristol’s port, largely built on slave-trading money. In 1809, Bristol had a floating harbour installed – eighty acres of tidal river were enclosed, at a cost of £600,000, allowing ships to remain constantly afloat – but it still wasn’t enough to match Liverpool’s growth. With the arrival of Liverpool’s deepwater port, along with the Bridgewater Canal and subsequent north-western canals, Bristol lost even more Atlantic trade.

By the early nineteenth century, the trading fortunes of Birmingham and Manchester had eclipsed Bristol’s. The collapse of Bristol’s port trade was deepened by the 1908 expansion of the Avonmouth Docks at the mouth of the River Avon, which could accommodate much bigger ships. The city docks finally closed in 1973.

You can diagnose industrial rise and decline in the civic monuments of the various cities. Birmingham and Manchester are largely nineteenth-century metropolises, their town halls and civic buildings planned on a vast scale; in a mixture of Gothic Revival, like Manchester’s Town Hall, built in 1877 by Alfred Waterhouse, and high classical, like Birmingham’s 1834 Town Hall, a gigantic, delicate Greek temple.

Bristol’s architectural treasures date from its eighteenth-century golden days – and preceding centuries, right back to the discovery of America – before it lost out to the north. Its golden years are reflected in the name of the streets: Washington Breach, Newfoundland Lane and Jamaica Street, recalling the profits made from shipping slaves to the West Indies, and bringing tobacco and sugar back to Bristol.

The best of Bristol’s terraces, particularly in Clifton, are late eighteenth century, before the financial collapse of 1793 brought on by the Napoleonic Wars. Credit was withdrawn and Bristol, on the cusp of a building boom, suffered badly. More than sixty builders and developers went out of business. The recession lingered on as late as 1828, when a cash-strapped developer applied to the Merchant Venturers, the entrepreneurial society that ran much of Bristol, for a licence to build much smaller houses on Cornwallis Crescent, in Clifton.6

Bristol’s industrial decline in the early nineteenth century came early enough for it to diversify. In 1934, despite the recent depression, J. B. Priestley described Bristol’s recovery:

[The city had achieved] a new prosperity, by selling us Gold Flake and Fry’s chocolate and soap and clothes and a hundred other things. And the smoke from a million gold flakes solidifies into a new Gothic Tower for the university; and the chocolate melts away, only to leave behind it all the fine big shops down Park Street, the pleasant villas out at Clifton, and an occasional glass of Harvey’s Bristol Milk for nearly everybody.7

When the modern industrial recession came in the second half of the last century, Bristol was better insulated than the colossal cities built on the back of the Victorian industrial boom. Because Bristol’s docks began their steep decline much earlier, the city wasn’t as badly affected as London and Liverpool by the British dock collapse of the 1960s and 1970s.

Since 1648, Liverpool had traded in slaves, cotton, tobacco and sugar. Through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, its trade with the West Indies and Virginia flourished. But Liverpool’s really golden days were that much later, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when it became Britain’s greatest Atlantic port: its docks received the bulk of American cotton for the Lancashire mills; in the 1840s, Liverpool began to develop its Atlantic liner business. The city’s population was 118,972 in 1821; 286,487 by 1841.

The fortunes of British docks weren’t helped by container ships, which first arrived in 1963. Thanks to containerization, companies could pre-pack goods in identical containers, which were then rolled on and off ships at both ends by lorries.

Gone were the days of dockers loading, say, 200,000 individual items on to a single small ship; thousands of dockers were left with nothing to do. These days, 27 million tons of containerized trade, 40 per cent of all British seaborne imports, arrives through a single dock, Felixstowe, every year.

Recessions struck the Midlands and the north from the 1930s onwards. By 1933, half of Lancashire’s prewar cotton trade had disappeared. Blackburn became known as Dole Town. In the late 1960s, British steel production began its decline, due to cheap foreign imports, with the national steel workforce collapsing to 16,000. By the time the Redcar furnace closed in February 2010, steel-making in Britain had shrunk to a small hub of works in Scunthorpe, Newport and Port Talbot.

In the 1980–82 recession, the West Midlands were hit much harder than anywhere else by the contraction in manufacture. Unemployment in Birmingham rose from 7 per cent in 1979 to 20 per cent in 1982.

This succession of body blows over half a century exacerbated the divide between north and south; one that survives today, even with the recovery of many northern cities.

New factories, in the genuine mass-production sense of the word, are rare but not unfindable. The JCB factory in Rocester, Staffordshire, and the Honda car factory in Swindon, Wiltshire, are both built on a grand scale. The 200 ceramics factories in the Potteries in the 1970s have now shrunk to thirty; but several of them, like the Emma Bridgewater factory, founded in 1985, are thriving.

In the old industrial heartland, the north’s cityscapes have survived through diversification: the art deco Wills tobacco factory in Newcastle, derelict for a decade after its 1986 closure, is now a chic block of flats. The Wills tobacco factories in Bristol have also been converted into flats, clustered round the Tobacco Factory Theatre.

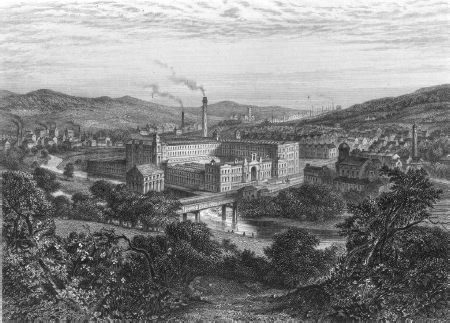

Post-industrial renaissance – Sir Titus Salt’s textile mill on the banks of the River Aire, built near Shipley, West Yorkshire, in 1851. The mill now houses companies, shops, restaurants and a David Hockney gallery.

Small-scale workshops are more the order of the day now, even if they are sometimes housed in old factories, like those in the old Bryant and May match factory in Garston, Liverpool. The factory now has a thousand more people, employed in dozens of small businesses, than it did in the original, single-use factory.

Still, for all its recovery, the north remains more dependent on government money and jobs than the south; the state stepped in to fill the gap when the industrial jobs vanished.

Coalition cuts, of roughly 410,000 public-sector jobs and £81bn of spending, will be felt that much more in the north, which has the highest levels of public-sector jobs in England. In the north-east, around 23 per cent of the workforce are on the public payroll; the figure is 21 per cent in the north-west.

The effects of the Industrial Revolution – and the Industrial Recession – still ripple through the housing sector, too. New housing developments in the north-west fell by 59.1 per cent in 2010, compared to pre-crunch levels. That figure fell by only 29.1 per cent in the south-east. Despite the national housing shortage, in Newcastle in 2011 there were still boarded-up terraces that once belonged to steel, coal and shipbuilding workers. In October 2011, the average house price in the south was more than double that in the north.8

Wherever house prices are higher, wherever private-sector employment is higher, and the closer you get to London, the more manicured the countryside is, after generations of cultivation and gentrification.

Political differences also shadow the north–south divide. The 2010 election divided rural Britain in two: largely Labour, SNP and Liberal Democrat north of north Yorkshire, largely Conservative anywhere further south, until you hit Wales and the West Country.9

That political division was even represented in the number of street parties held for Prince William’s wedding in April 2011. The Local Government Association reported that there were just four party applications in Liverpool, eleven in Newcastle and thirteen in Manchester. In the small borough of Richmond, south-west London, there were forty-four.

The north–south divide is deepened by the London effect – the magnetic power the capital has not just over Britain, but over the world. Before William the Conqueror invaded, London was neither the formal nor informal capital of England. Canterbury was the religious capital, Winchester the secular one. It was only in the eleventh century that London became first the informal capital of England, as the country’s biggest, richest city, and then the formal one. As late as 1338, London still had a population of less than 40,000; in the same year, Florence’s population was 95,000.

In the last thousand years, London’s supremacy over the rest of England – and Europe – has only intensified. London has become a vortex for the young and talented, sucking them away from other English cities; and for immigrants, too, who think of England as London and vice versa. London is now an international city, drawing in the super-rich: more than half the homes sold in London in 2010 worth £1m or more were sold to foreign buyers.10

London’s economy moves independently of the rest of England. During recessions, London is always first in and first out of a housing downturn, with the regions usually lagging by a year or two. The richest 10 per cent in Britain are more than 100 times richer than the poorest 10 per cent; the richest 10 per cent in London are more than 250 times richer than the poorest 10 per cent. Without London – taking out the richest and the poorest in the country – you end up with a much smaller divide between north and south.

As someone born and brought up in London, I find it harder and harder to find born-and-bred Londoners living in the city – and people are increasingly surprised to hear that I am one of them. I found it just as unusual trying to meet a native New Yorker when I lived in the city five years ago.

But even New York doesn’t dominate America, the way London does Britain. In 2011, there were almost as many annual daily trips on the Tube, 1.1 billion, as there are on the entire national overground rail network. Roughly half of all English bus journeys take place in London.

The north–south divide that has split England for a millennium has deepened dramatically over the last eighty years, with the decline of northern industry. Over the last twenty years, the divide has also shifted: these days, it isn’t so much between north and south, as between London and Not-London.