Straight out of rural dreamland – a First World War postcard of John Bull.

I’ve known the area between Bridlington and Wetherby for 50 years and it’s hardly changed. I found out why in the end – it’s grade one agricultural land, so the villages aren’t extended; there’s nothing for tourists, no tearooms, just these beautiful undulating hills.

David Hockney, on returning to his native Yorkshire after half a lifetime in Los Angeles. 1

It’s not just Yorkshire that has survived the modern age’s assault on the Englishness of England.

Across the country, big patches of rural land have fared much better than in, say, Ireland, where lax planning bodies have allowed all sorts of monstrosities through.

The Irish have rarely lived together in settlements along the English village model that helped keep the surrounding country untouched. Irish farmers’ deep-rooted attachment to the land – and the importance of land ownership in a place that was politically and religiously divided for so long – has meant that everyone wants a bungalow in its own field.

In Kerry, there’s a so-called ‘one-off house’ for every kilometre of road, a sad distortion of Eamon de Valera’s 1943 vision of an Ireland ‘bright with cosy homesteads’.2

The Wyndham Land Act of 1903 also allowed Irish tenants – 316,000 of them – to buy out their aristocratic landlords, leading to many more, smaller farms, proportionally speaking.

In England, more privately owned big estates have survived – leading to better preservation of the landscape, as well as larger fields. Whatever you might think of an unfair land ownership structure, it often makes things look more beautiful.

To an astonishing degree, much of the countryside retains its prewar look, despite England being the most densely populated country in Europe. Something like three quarters of all the moorland that has ever existed in Britain is still there – and the British Isles encompass the biggest area of moorland in the world.

The survival of the countryside is largely due to a series of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century rural preservation movements, begun when large-scale development was looming on the horizon.

London’s woods were protected by the Commons, Open Spaces and Footpaths Preservation Society, founded in 1865. The Guild of St George, created by John Ruskin in 1870, helped preserve the Lake District. The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, set up in 1877 by Philip Webb and William Morris, and the National Trust (1895) turned the preservation movement towards old buildings. The twentieth-century threat of urban sprawl was countered by Sir Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City Association – later, in 1941, to become the Town and Country Planning Association – and the Campaign for the Protection of Rural England (1925).

The greatest preserver of all was a piece of legislation: the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947, which outlawed ribbon development, set up green belts and imposed the obligation of planning permission. The first national park, the Peak District National Park, was set up as late as 1951, driven by the same impulse: as post-war rural England fell prey to the bulldozer, and the first motorways were planned, the imminent threat to beauty sparked off its preservation.

Urban parks, too, grew out of a desire to preserve blocks of green land against the encroaching tide of slate and bricks. Canterbury’s public park, one of the first, was set up at Dane John as early as 1790. The institution of public parks accelerated through the nineteenth century, as a direct response to spreading urbanization. In 1833, the Parliament Select Committee on Public Walks was founded to promote public parks. Until then, all parks in London were royal parks: Hyde Park had been Henry VIII’s hunting ground, expropriated from the monasteries.

You can chart the sprawling growth of London through the appearance of its parks, asymmetrical green gaps in the outwardly spreading lines of urban terrace: Regent’s Park, another royal park, was landscaped by John Nash from 1811 onwards; Victoria Park was built in the East End in the 1840s; Kennington Park was carved out of Kennington Common in 1852; Battersea Park was set up in 1861, when the flat, low-lying Battersea Fields were dramatically landscaped; Wimbledon and Putney Commons were preserved by an 1871 Act.

In Birmingham – where Victorian industrial tycoons left their suburban estates to the city – there is more parkland than anywhere in Europe. Later in the nineteenth century, local authorities took up the practice: setting up Terrace Gardens in Richmond in 1887 and Brockwell Park, Herne Hill, in 1892.

When Lord Rosebery – then Foreign Secretary, later Prime Minister – opened Brockwell Park, he said, ‘We have many parks, perhaps more parks than any capital in the world; but every day, gradually and by minute fractions, the process of building over small open spaces, the suburban gardens which are attached to the villas which are every day being pulled down, every day the process of destroying these is going on.’3

There was another burst of park-building after the war; in the 1940s came the idea of linked open spaces. This was realized in the 1970s in the Lee Valley Regional Park, stretching for twenty-six miles along the River Lee from Ware, in Hertfordshire, through Essex, before meeting the Thames at East India Dock Basin.

Victorian urban parks have survived well, while the handsome nineteenth-century buildings in the cities around them have often fallen to the wrecking ball – or the wrecking town-planner.

This division, between heavily knocked-about buildings and highly protected green space, is unusually English – and fits with a long-standing national rural obsession.

A preference for ancient rural Arcadia over urban modernism has been around for centuries. Most archetypal English views over the last millennium or so, in pictures, prose and poetry, have been rural. Most books about England are drenched, too, in rural sepia.

The Batsford guidebooks to Britain, which crystallized the typical view of the countryside in rich, travel-poster colour, from the 1930s to the 1950s, dipped into towns and villages; but only rarely, and then to examine medieval churches and inns, not cinemas, libraries or market halls.

This English obsession with the countryside is caught in Richard Ingrams’s England, written in 1990. It’s a witty, cynical compendium of all the things – run-down, urban and squalid, as well as rustic and wholesome – that are idiosyncratically English.

Ingrams said that he could easily have compiled a book called Going to the Dogs, reflecting the long-held English conviction that we are all irrevocably doomed. Just look at the index to the 1892, two-volume edition of Dr Johnson’s letters.

ENGLAND, all trade dead II 120; poverty and degradation, 150; sinking, 264; fear of a civil war, 286; times dismal and gloomy, 370; see also INVASIONS.

Still, for all its gritty realness, Ingrams’s book has a more-English-than-English cover – of evening light cast over a wooded valley, dappling the shaggy outline of an oak. The image of blissful, bucolic England triumphs again.

Our long-held obsession with the country helps explain why we produce so many good landscape painters, like Samuel Palmer, Paul Nash, John Constable, J. M. W. Turner and John Piper.

And it’s why, studies show, our favourite pictures are landscapes, with water, open spaces, animals and low-branched trees. They are often in watercolour, too; much more frequently than on the Continent.

Perhaps this is self-evident, an example of the Kingsley Amis Principle of Aesthetic Preference: nice things are nicer than nasty ones.4 But there’s another phenomenon lurking behind the popularity of landscapes. The English idealize the country in a way seen nowhere else in the world; even though – or perhaps because – since around 1850 more of us have lived in the town than the country.

Our love of the country is not just visible on book jackets. It’s there in the weekend sections of the newspapers, the countless articles on the joy of downsizing, on the nagging longing to chuck in city life and shift to a slower, more aesthetic, rural existence. When newspaper editors run a piece on quintessential England, it is invariably illustrated with a rural photograph.

This England, the quarterly illustrated magazine popular among expats – ‘For all who love our green and pleasant land’ – is an England of Palladian bridges in Wiltshire, island castles off Northumberland and cricket greens in Hampshire.

The images slip easily into the Big Book of English Clichés – an easy, fatal volume to draw from. The English have a devout faith in the existence of nice, but mythological, English characteristics, particularly the ones about us being eccentric, fair, polite, shy and decent. The idea of an unwrecked England fits neatly into the same anthology of national fairytales.

Terraced houses and Victorian town halls – things that are just as English as rectories and village greens – don’t get into This England because they are urban. They belong to That England, where things aren’t so picture postcard pretty.

We are the only nation – even in the English-speaking world – that refers to the rural part of our nation as ‘the country’; as if England only consists of fields, rivers, mountains and moorland; as if the urban bits don’t really count. We persist with the delusion, even while we secretly know it’s the urban bits that really count financially: that’s why we’re prepared to pay so much for our houses the closer we get to the middle of a city.

This division between town and country has been around since England was absorbed into the Roman Empire – itself really an urban civilization, living off cheap corn grown in the country. Country life is only idealized in predominantly urban civilizations like ours – where we are detached from the back-breaking work in fields that were, until recently, little more than factories with the lid off.

Rural idealization doesn’t happen in countries that remain essentially rural. The phenomenon doesn’t exist in France, where they still regard the country as a place for working farms, not for leisure.5

There’s a similar distinction in England between farmers who work the land and weekenders who use it for pleasure. Farmers, who view the land as a workplace, are unlikely to go for a walk – it’s like visiting your office at the weekend. Only rural weekenders see a country walk as a treat.

Our rural fantasies extend to our national figure. John Bull is a stout, red-cheeked farmer straight out of the hallowed, mythical countryside; and, all the while, real farmers are becoming an endangered species – the number of British farmers has tumbled over the last two decades, from 477,000 to 353,000.

John Bull was himself an artificial creation, invented in 1712 by a Scot, John Arbuthnot, who described him as an ‘honest, plain-dealing fellow, choleric, bold, and of a very inconstant temper’.6

Straight out of rural dreamland – a First World War postcard of John Bull.

This rural fixation is not always a fantasy, an artificial longing for a rural idyll that no longer exists. The country really does trump the town in the minds of real people, too, particularly among the upper classes.

From the early twentieth century onwards, the land-owning families of England demolished their London homes rather than sell their country houses. If Lord Sebastian Flyte’s family had held on to their London house and sold their country one, Evelyn Waugh’s novel would have been called Marchmain Revisited. But it is the city pile, Marchmain House, they sell when the current account begins to dwindle.

The Royal Family still choose Balmoral over the south of France for their summer holidays. In 1825, when George IV made Buckingham House his London palace, he plumped for an old country-house-style building, in a rural setting, rather than a new ordered urban palace, like Versailles or the Louvre. Buckingham Palace still has its distinctly Picturesque country house garden, with winding paths, a serpentine lake wrapped round an island, and a spreading lawn.

Country estates remained, and remain, the beating heart of the English aristocracy, while French nobles gathered round the court in Paris. With the monarch holding absolute power on much of the Continent, power accumulated around the urban court. In a parliamentary democracy like ours, power diffused into the regions, where landowners built their country houses and chose to be buried in the local parish church.

There’s a charming theory that English horse-racing was born the day Charles I was beheaded. Royalists retreated to their country estates and devoted themselves to horse-breeding. Meanwhile, Oliver Cromwell improved the bloodline of English horses by importing purebreds from the Middle East and Italy.7 When the revolution hit France 130 or so years later, the grander families, if they escaped the guillotine, sold the country château and hung on to the hôtel particulier in Paris.

Rural idealization was helped by country living standards, higher here than on the Continent. The rural life was a less bleak, more comfortable prospect in Britain at a much earlier stage than in other countries. By the end of the nineteenth century, most of the country was in reach of the new rash of railway lines, and so never far from London. The arrival of the car brought the metropolis even closer.

‘Here today – in next week tomorrow!’ booms Toad in The Wind in the Willows, as he dons his driving gloves and careers through Edwardian Berkshire.

Throw in several daily postal deliveries in Victorian England, and you need never feel very far from the action, however remote your house. Because the whole country had been so heavily settled, the chances of complete isolation, unless you went in active search of it, were low.

And, because England had been settled for so many centuries, there was usually a sophisticated social structure in place. Even in the furthest corners of the country, the ever-present infrastructure of big house, church, parsonage and market town produced a mix of classes and fortunes, providing a secure berth for people of any background. Practically all 1,600 market towns in Britain had this infrastructure established by the eighteenth century.

This complex, ancient social structure, combined with England’s smallness and hospitable weather, mean the English tend to stay close to where they were born; despite the ease of movement that comes with a small country and extensive transport links.

At a New York talk in 2006, Tom Wolfe was asked what he thought the biggest technological innovation of the last century had been.

‘I know I should be saying the internet or the computer or something,’ he said, ‘but, actually, for me, it’s still the car. Until the middle of the twentieth century, my ancestors had lived in the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia, ever since the late eighteenth century.’

‘Because of the car, and the social acceptance of moving, my family now all live in far-flung parts of the United States. Something like 20 per cent of Americans live within fifty miles of where they were born.’

In an increasingly mobile society, the English, too, are beginning to move further from their birthplaces; but, still, not to the same degree as in America.

We have largely stayed in the same place for generations: in 1997, scientists discovered that Adrian Targett, a 42-year-old history teacher, living near Cheddar, Somerset, was a direct descendant of Cheddar Man – Britain’s oldest complete skeleton, who’d lived in Cheddar in around 7150 BC.8

Part of the reason is that family roots were planted that much earlier here. In the American Midwest and beyond, those states were only substantially settled in the last century and a half. Few of today’s Midwesterners are likely to have lived there even as long as that. Even on the East Coast, settled for 400 or so years, not many Americans have lived in the same state for more than a century.

When, in 1985, Route 66 – the 1926 road running across America from Chicago to LA – was superseded by a number of interstate highways, towns that had only recently been built to service the road died. Empire, Nevada, a company town built by the United States Gypsum Corporation in 1923, was completely shut down in 2011, when the gypsum business collapsed in the construction recession.

But when the Cornish tin mine industry disappeared in the last century, the towns that had flourished on the back of it clung on. Their medieval roots had been put down before the tin industry boomed; they survived long after the mining had gone.

This lack of mobility explains why English regional accents survive, and differ over such short distances. Reading is only forty miles from London along the M4 corridor, and yet a distinctive rustic burr still survives in the old Berkshire market town. In America, you have to drive 225 miles south of New York before you hit Washington DC and encounter the semblance of a southern accent. In England, 100 years is nothing, and 100 miles is enormous; in America, it’s the other way round.

This cultural and aesthetic worship of the country meant rural England became more than an agricultural factory for producing food. It was necessary that it should be beautiful, too. In other countries, food production and scenic beauty are different things. When Americans talk about the countryside, they mean the Rockies or the Great Lakes, not the wheat-growing prairies. On the Continent, landscape means the mountains or the lakes, not the agricultural areas. Here, beauty and agricultural productivity are combined.

The urban–rural split determines which towns are thought right for day trips, too – Oxford, Cambridge and York, say, untouched by the Industrial Revolution, with the Cowley car works nicely tucked away on the outer fringes of Oxford.

Who goes on a day trip to marvellous industrial and trading cities, like Manchester, Leeds or Cardiff, kept off the tourist schedules because they are too modern and urban, and not medieval, rural and undeveloped enough?

As part of the reaction against the Industrial Revolution, not only did we fetishize the country, but we also tried to ruralize the city, with our cult of the back garden, and our invention of the first garden cities.

The three most popular house names in Britain are The Cottage, Rose Cottage and The Bungalow. Even just having a name – any name, but particularly a rural name – makes your property 40 per cent more likely to be viewed by prospective buyers. There is still a rarity value attached to addresses without a number in them: only 1.4 million of the 26 million houses in Britain are named.9

A similar rural dream dictates the English lifetime structure of working in the city in your prime, before retiring to the promised land – the country – in old age. At the heart of the daily commute, too, there lies a deep-seated desire for the country, along with the availability of cheaper house prices. It’s worth a daily three-hour return trip, so the thinking goes, to glimpse the sun set over the neighbouring field, before you go to bed at nine to prepare for the dawn commute.

Still, despite the cherished place of the country in English hearts, very few of us ever do end up downshifting. Town mice may dream of being country mice, but it remains a dream.

The overwhelming feature of modern England, ever since the Industrial Revolution, has been rampant migration from country to town, the explosion of the suburbs, and the emptying of the countryside. Eighty-six per cent of England is rural, and less than 8 per cent of the country is under concrete. But only 20 per cent of the population live in the countryside.

That urbanization process is intensifying across the planet, as Third World countries industrialize, and their populations begin to appreciate the greater riches and opportunities offered by cities. Cities reduce poverty and cut population growth, with people swapping big agrarian families for the smaller families found in the urban West.

The urban migration phenomenon applies not just to people in Third World rural areas moving to Third World cities; it also applies to Third World farmers moving to Western cities. There’s a story of a teenage girl in Tower Hamlets, east London, who tells her sister how she longs to go back to the family farm in Bangladesh.

‘You’re welcome to it,’ says her sister. ‘By the time you get there, everyone else in the village will have left to come here.’10

The population shift from country to town is starkly clear on any rural train ride. After taking a five-hour train journey from Pembroke to a party in Dorset recently, I asked the Polish lawyer next to me at dinner what made the fields so English-looking.

‘The huge difference between rural Poland and rural England is how empty the English countryside is,’ she said. ‘Go through fields in a train in Poland and they’re still being worked on by the people who own them. Take a train through rural England and you might not see a single person in a field for several hours.’

She was right. I remembered only one person in a field on my train journey from Wales: a man with his dog, out for a walk, using the country for pleasure, not a farmer working his land.

Britain industrialized – and was heavily urbanized – that much earlier than Poland. Its individual landholdings are much bigger, too, with major landowners farming as much as 100,000 acres, and cutting down on manpower as a result. In Poland, peasants might still live off a third of an acre, and cultivation is much more labour intensive and much less mechanized.

Still, this one-way traffic to the city doesn’t stop us mythologizing the countryside, and equating it with the nation as a whole.

‘It was a sweet view, sweet to the eye and the mind,’ Jane Austen wrote in Emma, ‘English verdure, English culture, English comfort, seen under a sun bright without being oppressive.’

‘English’ here means ‘rural English’. That was understandable in 1815; the Industrial Revolution may have been in full swing, but towns and cities were yet to dominate England. But, even in the modern age, the equation between England and rural England has continued, an equation that hasn’t been accurate for at least 250 years. It doesn’t stop us believing in it.

The English attachment to the countryside and its ancient buildings is manifested in the vast membership of the National Trust. With 4 million members, it is the biggest heritage membership society in the country; much bigger, proportionally, than any other national conservation group in the world. It has overseas arms, too, like the Royal Oak Foundation, which gives Americans membership of the Trust – and a shared delusion in England as a predominantly rural country.

1,800 English country houses may have been demolished since 1800 but, still, 50 million people visit one of the surviving stately homes every year; even if most of those visitors, after a day in the country, return to an urban home. Our national parks are just as adored. The Peak District in north Derbyshire is the second most visited national park in the world, after Mount Fuji in Japan.

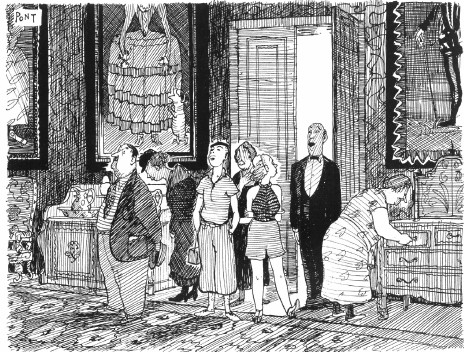

‘The British Character. Keen interest in historic houses’, by Pont in Punch, 8 July 1936.

We may not be the best country at producing artistic or musical geniuses. No Beethovens or Mozarts have sprung from ‘Das Land ohne Musik’ – the land without music – as England was called in a 1904 book by a German writer, Oskar Adolf Hermann Schmitz. But no country has as many individual rural preservation and conservation societies.

One art we are exceptional at is preserving rural beauty. Our poets and writers are still concerned with the pastoral, as they have been for centuries. No other European country publishes as many bird and plant books; no other similar-sized country has a million-strong bird appreciation society; no other country has an allotment system on such a vast scale; no other country is as obsessed with gardening.

While we have ring-fenced the beauties of the country, much of the best of urban England has gone – particularly its once untouched market towns and cathedral cities. But, then again, it’s debatable whether the best of England ever really existed in the first place. In England, the good has always driven out the best. We never hit the heights of urban beauty seen in, say, Renaissance Florence. The English mind is too cautious – and sometimes too philistine – for that sort of grand-scale beauty.

Because of our make-do-and-mend, hodgepodge approach to urban planning, the idea of recasting a whole city in Renaissance style is anathema. But, so, too is the CeauŞescu School of Architecture – razing most of Bucharest to inflict a new brutalist landscape on the Romanian people; even if England’s own CeauŞescu, John Prescott, had a pretty good go at it, paving Kent with building developments, tearing up decent Victorian terraced housing in the north-west with his grotesque Pathfinder project.

We are just too used to muddling through, incapable of seeing the grand projet through to the end. Just look at the results of the biggest national architectural project of the last half-century – the Dome. Weep by all means, but be grateful that we don’t try large-scale architectural projects too often.

It’s the same reason why Nazism never took off here – the bloody-minded, lazy, don’t-tell-me-what-to-do, obsessive privacy of the English, combined with the tendency to mock anyone who does tell us what to do.

The English are tolerant, unconfrontational and, on occasion, unpleasant enough to let an Oswald Mosley, or a Nick Griffin, come to prominence. But they’ll only let them get so far before they take against being shouted at.

And the same goes for the ugly changes to our urban landscape. Most cities and provincial towns have been scarred in some way, but the decline has only gone so far. Eventually, slowly, we come to our senses; and that widespread English love of the old, the picturesque and the asymmetrical ends up eclipsing the fashionable, small but powerful lobby behind the new, right-angled, ahistorical ugliness.

England is now a sort of halfway house – between modern uglification and ancient beauty; between shabbiness and neutered cleanliness; between Ye Olde Preserved Rural England and a rather less dazzling urban truth.

Halfway houses are difficult to describe. It’s not so much ‘How long is a piece of English string?’ as ‘Which piece of the string are you looking at?’ The manicured section of country house life laid on for the benefit of Japanese tourists and members of the National Trust? Or the steel, concrete and glass, light-industrial estates that flank the railway line from Liverpool Street to Cambridge?

When I asked Norman Stone, a former Professor of Modern History at Oxford, about the relationship between the English and the look of England, he paused for a moment and then said, ‘Well, I was struck by the quality of the flowers when I first came down from Glasgow on holiday in Lincolnshire, with some cousins in 1954, when I was thirteen. But then I can’t really answer that question without getting very boring about medieval landholding laws.’

That, perhaps, is as good an answer as any. England has got some very good flowers and some very old laws.

On the surface, the two things have little in common; but they both grow out of a shared soil, climate, geology and geography; an unusually beneficial combination for the stable, long-term survival of Homo Britannicus, his legal system and his national flora.

A variety of flowers and a long-standing legal infrastructure. It’s hardly as poetic as a ‘precious stone set in the silver sea’. But it’s a rather more down-to-earth, more accurate description of a place where people still just about rub along together; a place that still looks pretty unusual and – still, sometimes – unusually pretty.