I will now describe a few static positions, used by numerous body psychotherapists as references or positions to use by default. They are compatible with the requirements of orthopedics, physical therapy, and hatha yoga. It is usually asked of the person who is using these postures that he maintains the natural curvature of spine. This requires a tonic balance between the muscular chains that structure the front and back of the body. These are all ideal postures that are promoted by experts.

Some may need to consult a book on anatomy or an online search engine for definitions and illustrations. I do not know of a book that contains all of these notions.

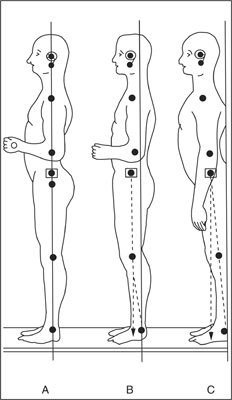

The physical therapists often evaluate a static standing posture with the plumb-line method (see figure A.l).1 They ask an individual to stand as straight as possible, knees unlocked, with the nape of the neck elongated. The feet are parallel or in the shape of a V (heels touching). In this posture, all of the muscles that permit this stretching (feet, legs, pelvis, back, nape of the neck, cranium, abdominal muscles, etc.) must be toned but not tense. The muscle tone in the front and in the back of the body is in balance. If the required muscle tone is present, and there is no skeletal deviation, the body segments align themselves automatically to provide the best possible balance. Ensuring a minimum of tension in the muscular system in all of the muscles is the criterion.2

FIGURE A.1. Reading of the posture using the “plumb line” method. (A) An ideal vertical standing position; (B) a restful standing position; (C) a standing-at-attention position. Source: Bonnett and Millet (1971, p. 695).

This ideal alignment places the ear, shoulder, pelvis, and middle of the foot on the same axis. A plumb-line that is held up to the side of the body from the profile ought to pass in front of the ear, the shoulder, the articulation of the pelvis, and arrive somewhat in front of the ankle. With practice, the physical therapist abandons the use of the plumb-line, because he has learned to analyze the alignment of the body as if there were a plumb-line. He will mostly use this device so that patients can learn to analyze their alignment when they are standing in front of a mirror.

Most Europeans are aligned toward the back: the plumb-line passes in front of the pelvis, shoulders, and ears. If you place these individuals in an ideal vertical standing position, they generally have the impression of leaning forward; they are afraid of falling. Yet if you test their balance by lightly pushing the chest backward, or the shoulder blades forward, they discover that they are more solidly anchored to the ground in this position. We thus notice that to align an individual also requires a reeducation of bodily sensations.

The Hindus and the Egyptians of old were already marvelous architects and had mastered geometry. They used the plumb-line to construct their homes. They imagined that the body balanced itself around an invisible axis that passes through the body’s center of gravity while standing. This center is situated in the middle of the abdomen, under the navel (a bit lower for a woman because, on average, her pelvis is heavier than a man’s). For the standing position, it therefore consists in aligning the perineum, the belly, and the fontanel, as if a perfectly vertical axis traversed the middle of all these body segments, and planted itself into the ground in between the soles of the feet. This imaginary axis of the vertical body that passes through the body’s center of gravity is referred to by the body specialists of almost all cultures, from yoga up to the theories used by the whirling dervishes of Turkey. We encounter this metaphor in several schools of dance that teach the necessity of sensing in oneself an axis that stretches out, in psychomotor schools of scientific inspiration, and in most schools of body-mind aproaches.3 For example, we ask some people to stand up, eyes closed, and imagine roots coming out of their feet and reaching deep into the earth. To regulate the position of the head, it is often suggested to imagine that a thread ties the fontanel to a star above the fontanel, and this thread tugs in such a way as to elongate the nape of the neck and the spine between the shoulder blades, which induces a lowering of the external part of the clavicles.4 Ideally, the clavicles form a straight line. It often happens, when we take a workshop in bodywork, that the instructors suggest that you feel your feet getting heavy around the axis and your head rising toward the star you were asked to imagine.

In this kind of work, it is often asked of the individual carrying out the exercise to sense the lateral distribution of body weight on the soles of the feet. Does the right or left foot carry more of the weight? Is the weight more on the inside or the outside of the feet? In both cases, it is the balance between the feet that is sought, with a weight that anchors itself at the center of each foot.

With his colleagues, Alexander Lowen established a series of postures that allowed patients to increase their awareness of a series of connections between impressions, breathing and postures (Lowen and Lowen, 1977). The posture that is most often used is called “grounding” (see figure A.2). It was already used in the Chinese martial arts, but Lowen works with it in his own fashion. The basic bioenergetic position is described as follows:

FIGURE A.2. The basic grounding position in bioenergetics.

By default, Lowen asks the patient to be as relaxed as possible, let go of his breathing, and breathe with an open mouth. Breathing through the mouth encourages the advent of vegetative reactions and emotional expressions. Breathing from the nose is a way to diminish these reactions when it is necessary. In tai chi chuan, it is often recommended to breathe in from the nose and to breathe out by the mouth.

There are two basic criteria to characterize sitting:

From an orthopedic point of view, there is only one way to sit. It is roughly the one that is automatically set in place by a person who sits comfortably in a lotus position: the person is sitting on the ground, the right foot high up on top of the left thigh, the left foot high up on top of the right thigh, in such a way the heel of the right foot is near the navel.6

The physical therapist7 typically proposes that an individual sit on a horizontal seat, a bit higher than the knees. The “correct” position of the pelvis is to imagine that the base of the pelvis is a three-legged stool that supports the weight of the upper body. The two “back feet” are the ischia, and the third is an imaginary extension of the perineum when it is as close as possible to the seat. The dorsal face of the pelvis8 is roughly at a 90° angle to the support surface. The two bones of the pelvis that frame the lower abdomen and the genital region are leaning slightly forward.9 This position of the pelvis is the best possible base to sustain the flexibility of the spinal column when someone is sitting, and it does not block any ongoing respiratory movements. Furthermore, the vertical position of the hip bone supports the uprightness of the lower back and imposes the necessary curvature. This position also tones up the rectus and obliquus abdominal muscles—just what is needed.

In Europe, many people have difficulty staying in this position for any length of time. In talking with them about their discomfort, it is possible to obtain a lot of information pertaining to their habits and muscular tension. It is sometime useful to recommend an approach to reeducate the relevant muscles and sensory-motor circuits (hatha yoga, the Mathias Alexander technique, Feldenkrais schools, Rolfing, etc.).

Going from psychoanalysis to body psychotherapy, Reich kept one constant variable: the patient is, more often than not, lying down on his back on a couch. Yet the therapist is now sitting next to the patient and even sometimes invites a visual contact.

When I speak of the basic Reichian posture (see Figure A.3), I refer to the following position:

I have not found any text in which Reich describes this position. I have reconstructed it from discussions with individuals who worked with Ola Raknes (e.g., Gerda Boyesen, Bjørn Blumenthal), and with Eva Reich. This posture is also compatible with all of the cases described since 1933. This was Reich’s default position; he sometimes observed someone standing or conversed with a patient who was sitting down.

FIGURE A.3. The basic vegetotherapy position.