I have distinguished two principal phases in Wilhelm Reich’s career:

Reich the body psychotherapist only existed in the transition phase between his career as a psychoanalyst and the establishment of Vegetotherapy. Among his collaborators and students, we find at least four different kinds:

It is mostly from among the third and fourth groups that we find the founders of body psychotherapy as it existed in 2000. The common goal of these approaches is the creation of a form of psychotherapy that has explicit organismic goals.

The distinction between body psychotherapy and a Reichian organismic psychotherapy is presently a work in progress. The attempt to clarify these forms of intervention is rendered more complex by the fact that psychotherapy is a recognized discipline and often reimbursed, whereas the therapy of the organism remains a field the institutions refuse to recognize. Some Reichians sought to present their work as a form of psychotherapy for political reasons. Thus, numerous schools whose goals are all of the regulatory systems of the organism promise their students a formation in psychotherapy that is not recognized by institutions. It seems to me that a clearer position would permit certain schools to fight to have organismic therapy recognized because they have a real usefulness, instead of wanting to have their approach recognized as a form of body psychotherapy.1

This sowed an important confusion in the domain. We find an analogous debate with the behavioral and systemic therapy approaches that treat behavior and not really the psyche. Again, the fact that these approaches are not psychotherapy, in the strict sense of the word, does not take anything away from their relevance.

The problem is as much on the side of the schools that could not survive in the current context without claiming that they are a psychotherapy school, as on the side of the institutions that refuse to recognize the therapies whose goals are the great regulatory systems of the organism, and opt for a fuzzy view of psychotherapy. All share in the confusion. The institutions do not know how to define psychotherapy2 and do not want to recognize work on the regulators of the organism or on behavior as different forms of intervention. Practitioners are afraid to provide an explicit definition of their field, as it might weaken the chances that their school will be included in the list of reimbursed treatments.

In the following sections, I describe the development of the neo-Reichian therapies that present themselves as having a psychotherapeutic goal by insisting on the difference between forms of treatment that mostly focus on the organism and forms of treatment that mostly focus on the psyche. It is understood that the fact of including the psyche in the dynamics of the organism and interpersonal interaction as a regulator of the organism make a sharp distinction between the two domains impossible.

If the legal repression against Reichian thought ceased at the end of the 1960s, it is still difficult to pursue an academic career in the 2000s if we accept some of Reich’s ideas.3 In the 1950s and 1960s, the political and academic repression of Orgonomy generated chaos in the field of body psychotherapy. Only now are we painfully emerging from that chaos. This situation engendered a vicious circle. It was impossible to access a serious formation; therefore, even people who wanted a serious formation were insufficiently trained. It was then easy to disqualify the clinical research on the body-mind dimension inspired by Reich, by assuming that all those who used his theory for their research were poorly trained. There were many traps set by this situation for the next generations. The more visible ones hid the more subtle ones. It is therefore as intellectual adventurers that the students of the 1960s and 1970s entered into the domain of body psychotherapy.

In the following sections, I show how body psychotherapy movement succeeded in restructuring itself without letting go of the most interesting aspects of Reich’s proposition. This endeavor required a reformulation that dealt with Reich’s Idealistic theses that impeded a serious reflection on body psychotherapy. After all, it is important to distinguish between the sympathy we may have for an individual, however brilliant he might be, and a domain that needs to develop itself for the interest of all: patients and researchers in particular.

Having showed that Orgone therapy aims at global organismic regulatory systems that are beyond the psyche, Reich demanded that only physicians be authorized to practice his approach. This requirement is not innocent. He suspected that all of the hyenas of the therapeutic marketplace would throw themselves on his carcass after his death. That is why Orgonomy remains a domain reserved, almost hidden, for a few physicians who constitute the membership of the American College of Orgonomy around personalities like Ellsworth Baker (1967). Moreover, there were good reasons for this. I even met, in the 1970s, self-taught “practitioners of Bioenergetics” who asked their patients to explore their inner fantasies on holidays in a “psychotherapy” group. They then sold the content of these fantasies to travel agencies, who wanted to know what images could be efficiently used for publicity. There certainly was a free-for-all that was created around Reich’s name after his death.

While the persecution against the Reichian movement was strong, the students of Reich were aware of the medical option. Alexander Lowen, for example, was a teacher of gymnastics and relaxation. Because he was passionate about everything that dealt with the coordination between mind and body, he underwent psychotherapy with Reich. Wanting to continue to work in this domain, he obtained his medical degree before creating Bioenergetic analysis.

In Europe, Reich was mostly represented by Ola Raknes, a psychologist in Oslo, and A. S. Neill, a famous educator. There was greater flexibility regarding the association between Orgone therapy and medicine. In autumn 1947, Gerda Boyesen attended a conference by Trygve Braatøy that was an important experience for the development of her thinking. He had then declared that to become a vegetotherapist, “it was necessary to be either a physician or a physical therapist” (Boyesen, 1985b, p. 14). Many years later, Boyesen decided to follow his advice and complement her training in clinical psychology by becoming a physical therapist. Federico Navarro (1984) is a neuropsychiatrist. He developed his view of Vegetotherapy after training with Raknes. Reich and Raknes both had had an excellent formation in Psychoanalysis. This was not the case for most physicians who were keen about Orgonomy.

The very influential David Boadella4 did university studies in pedagogy (which included studies in psychology and in the humanities). He also studied the biological bases of behavior at the Open University of London. He then studied for a dozen years with sociologist Paul Ritter, who had been trained in Vegetotherapy by a student of Reich, Constance Tracey. A personal process in Vegetotherapy with Paul Ritter (Ritter and Ritter, 1975) was part of his formation. In his writing, Ritter tries to promote a lifestyle and a libertarian and humanistic morality that he identifies as Reichian. This training is discussed in Ritter’s journal, Orgonomic Functionalism, which appeared for several years (40 issues) and in his books. We have seen how angry Reich was with some of Ritter’s propositions. He had asked Neill to warn Ritter and Boadella that they were no longer to associate his name to their school. Nonetheless, with Neill’s support, David Boadella continued to explore Reich’s thinking by undergoing Vegetotherapy with Ola Raknes (when he was in London) and with Doris Howard. He then went to the Open University to take up his studies in the biological bases of behavior. It was difficult to obtain a more rigorous course of studies for body psychotherapy in Great Britain. Boadella (1987) established a school of body psychotherapy called Biosynthesis,5 which became one of the principal neo-Reichian schools in the world (especially in Europe, the United States, Brazil, Australia, and Japan). This school attempts to synthesize, as a coherent whole, the knowledge developed in the neo-Reichian schools. To accomplish this, Boadella created the journal Energy & Character in 1970. This journal welcomed all who wanted to express themselves in it. For a long time, it was the only real intellectual link between the neo-Reichian schools and the only attempt to create a shared intellectual structure.

One of the most well-known Reichians in California was Charles R. Kelley. He had trained as an experimental psychologist and had been in therapy with Reich. He then undertook experimental research on the orgone and became an expert on the analysis of the ocular segment.

From that point forward, the Reichian methods entered into a confusing march of ideas and methods. The domain was dispersed into small schools, grouped around teachers who were more or less trained, mostly situated in California, New York, and London. It was a walk through the desert for the domain. The only place where body psychotherapy was practiced within institutions was in Scandinavia (mostly Oslo, as we will see).

A new conception that concerns man’s destiny in the world and is not alien to the cultural movements of the ‘60s has given rise to the emergence of an extensive range of techniques of self-actualization and personal growth. A common radical to all these techniques is the anti-intellectualism that stresses emotional development. Some of these techniques are based on psychoanalysis; others have a strong oriental flavor. Some body-centered techniques have even introduced the use of drugs and sexual contact with the clients. . . . The boundaries of psychotherapy have become blurred. Not only encounter groups, but also jogging, aerobics and even golf could be considered psychotherapies in this context. (Jose Guimon, 1997b, The Body in Psychotherapy, p. 3f)

The youth movements that arose as early as 1966 in the United States and then Europe brought Reich’s work back into fashion. It was a tidal wave that forced the authorities to moderate their persecution of the Reichian milieus. The academic milieus adopted an attitude that blended a pitiful smile, irony, and disdain. Body psychotherapy has to have recourse to a sort of popular suffrage to resist political and academic repression. This strategy paid off! Body psychotherapy became a social phenomenon. A form of impulsive speculation, often imaginative and rarely well framed, became fashionable with the neo-Reichians of the day.6 Without an ethical backbone, these movements associated themselves to different fashionable methods, sometimes to drug use (especially hashish and LSD) and to popular gurus.7 Sexual ethics became as blurred as it was at the beginning of psychoanalysis, because some profited from a reflection on the taboos to promote as an expression of emotional health their perverse sexual attraction for their patients.

Reich could have easily agreed with the youth movements of the ‘60s but probably not with the “New Age” movements of the ‘80s. The generation of Gerda Boyesen and Alexander Lowen had just a humanitarian interest for leftist theses and were astonished to see hundreds of long-haired intellectuals enter their training programs. Up until then, they only had had as students a few well-educated individuals, deeply interested in approaches such as those of Reich. There was a bit of everything in this new generation. Some were really interested in the notion of body psychotherapy, while some wanted to earn as much as a psychiatrist by completing just a few workshops a year for training.8 Gerda Boyesen and Alexander Lowen surfed this wave without really understanding what was happening to them, but they appreciated the fame, admiration, and money this fashion brought them. These students can be grouped into three basic categories:9

This list indicates to what extent training programs of the period attracted a heteroclite population. Training was open to anyone who could pay. The courses were good enough to allow some of these students to become excellent psychotherapists. However, the criteria for selection were low.

For some individuals with a university education, the formulations advanced in the schools of body psychotherapy in the 1970s were embarrassing, given to what extent they had become folkloric.10 However, they admired what could be experienced, thanks to these approaches. The basic strategy of these intellectuals was to learn what there was to learn in the schools of body psychotherapy of the time, while seeking to participate in the new developments in psychology and psychotherapy. One of the reasons the schools of body psychotherapy could not be ignored was the way they approached problems associated with the affects. The permission to experience one’s organism and the forces that animate it intensely was far beyond what traditional systems of education allowed one to imagine. Sustained by a spirit of discovery associated to student movements of the 1960s, a number of intellectuals explored these pathways with a creative passion.11

In all of this chaos, a new way of approaching psychology begins to emerge in what is known as humanistic psychotherapies. To be trained, students now need to integrate a variety of relevant set of concepts, techniques, and personal experiences. Experiential workshops became a source of information as crucial as books and courses. It is no longer enough to be familiar with one approach, as required by the traditional psychotherapies. Students learn to know their field by participating in experiential workshops given by a variety of schools. They want to integrate in their personal development a combination of habits, theories, and beliefs.

Distressed by the reactions incited by new developments in body psychotherapy, most Scandinavians withdrew into their shell. There, body-mind therapeutic interventions remain anchored in institutions. In Oslo, practitioners abstain from publishing in a language other than their own. Thus, they preserve an island of competence and tranquility. The Danes are more willing to present their work to the world. That is especially the case for the Bodynamic School (MacNaughton, 2004; Marcher and Fich, 2010), founded by Lisbeth Marcher with, among others, Marianne Bentzen, Peter Bernhardt, Erik Jarlnaes, Peter Levine, Ian MacNaughton, and Lennart Ollars.

In 1980, it became quite evident to some new members of the domain of body psychotherapy that their domain was going to sink if it were not supported by knowledge based on a more robust ethic of knowledge (Heller, 1993d). Numerous individuals attempted to reconstruct a connection between the human sciences of the time and the practices of body psychotherapy. Here are a few representative names of this movement who influenced the thinking in this text: Maarten Aalberse, Jacqueline and Yves Brault, Christine Caldwell, Jacqueline A. Carlton, George Downing, Alison Duguid, Peter Levine, Mark Ludwig, John May, Gustl Marlock, Pat Ogden, and Luciano Rispoli. This is not an exhaustive list. Most of them published in Energy & Character, Adire,12 or USA Body Psychotherapy Journal. The expansion of basic references in body psychotherapy that followed developed in two directions: toward science and toward spirituality. The source reference for the second was Jung, for whom all available theories and knowledge can become useful and relevant for the development of psychotherapy.

The founding of the European Association of Body Psychotherapy (EABP) on December 20, 1988, by Bjørn Blumenthal, Malcolm Brown, and Jay Stattman13 allowed for strengthening this attempt at reformulation by bringing members from most of the schools together to meet and dialogue with each other. A similar association was founded in the United States in 1996: The United States Association for Body Psychotherapy (USABP). Finally, body psychotherapists were able to differentiate the particularities of their approach from what could be considered a common ground of knowledge. This font of knowledge is in fact only partially in common, because most ideas are used differently in several schools, but none by every school.

The authors I have just mentioned continued their work of reconstruction in the 1990s.14 The strategy that is taken is to establish a dialogue with the different ways of approaching the human being that they learned to appreciate in becoming body psychotherapists and the knowledge established in other approaches. The critics in medical and academic milieus are confronted head on. The standout event of this endeavor was the publication of Körper und Wort in der Psychotherapie: Leitlinien für der Praxis[Body and Word in Psychotherapy: Guidelines for a Practice] by George Downing in 1996.15 The work set in motion by this generation of body psychotherapists is analogous to that undertaken by the generation of Otto Fenichel in Psychoanalysis in the 1930s. They were trying to reformulate the psychoanalytic theory by stripping it of its mystical origins (hypnosis and mesmerism) and creating some bridges between clinical work and the recent formulation from the sciences: “Psychoanalysis as it is now constituted undoubtedly contains mystic elements, the rudiments of its past, as well as natural-scientific elements toward which it is striving” (Fenichel, 1945a, p. 5).

Since the 1990s, the whole world of psychotherapy has been trying to free itself from the constraints of particular schools without losing what makes certain methods so valuable. Such an endeavor is risky, because the methods, spirit, and theory of an approach make up a coherent entity. A psychoanalytic method (e.g., free association) used in another setting may lose or modify its relevance. Nevertheless, the need to go beyond a form of knowledge structured by particular schools became a necessity.

This reflection is supported by setting up diverse ethics committees capable of ruling on complaints made by colleagues or by patients. One of the discoveries made by these committees is that, contrary to what rumors led some to believe,16 there did not seem to be more sexual boundary violations between psychotherapist and patients among body psychotherapists than in verbal approaches. The phenomenon of patient abuse seems to be a sadly human inclination that is relatively rare but persistent. These ethics committees deal with complaints of patient abuse more directly and publicly than most other therapeutic approaches do. As soon as touch and trust become an important mode of intervention, a particularly rigorous ethic and deontology become indispensable. Setting up these ethical standards is a central issue for the European Association of Body Psychotherapy (EABP).17

Imagine how it must have been fascinating for a psychotherapist to be in Oslo in 1934. The insatiable Fenichel and Reich delved with pleasure into countless arguments. They discussed not only with colleagues but also mingled with the artistic and intellectual life of the city. I imagine that Clare Fenichel and Elsa Lindenberg sometimes brought the debates back to the use of the body in psychotherapy or to the relevance of Vegetotherapy to understand what is going on for a ballet dancer.

The debate between Fenichel and Reich on the way to include the body in psychotherapy became a subject that could not be overlooked. The Scandinavians have a tradition of body techniques so anchored in the customs of their culture that the subject imposed itself. Reich’s and Fenichel’s colleagues were certainly interested in Elsa Gindler’s and Rudolf Laban’s approaches such as they were described by Clare Fenichel and Elsa Lindenberg, but they also incorporated the entirety of the body methods appreciated in these regions. The idea of situating the affects, the thoughts, and gymnastics as different ways of approaching the regulators of the organism was, in any case, fashionable because Cannon’s books were representing recent medical developments in the United States for the European medicine of the day. The connection between Cannon’s theories and the body-mind approaches was Edmund Jacobson’s relaxation. The Autogenic training of German psychiatrist Johann Heinrich Schultz was also often used.

Even if Reich pretended to be interested only in the organism, many in his entourage were psychotherapists and psychiatrists for whom the use of body techniques with their patients one way or another had become an important research topic. For most psys stimulated by this debate, the emerging discipline evoked by the discussions between Fenichel and Reich was important, not necessarily their proposals. Vegetotherapy was a reference because it was the first body-mind technique developed by a psychotherapist; once the interest in integrating body and psyche became manifest, it was this theme (more than Reich’s technique) that was explored. It was evident for the people educated in body techniques that Wilhelm Reich was a brilliant beginner. His proposition was convincing, but it had to be refined.

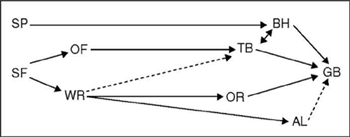

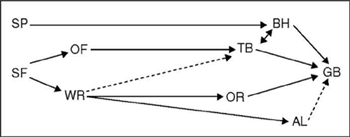

FIGURE 19.1. Affiliations of the Oslo schools in the 1960s. SF = Sigmund Freud; SP = Scandinavian physiotherapy; OF = Otto Fenichel; WR = Wilhelm Reich; TB = Trygve Braatøy; OR = Ola Raknes; BH = Bulow-Hansen; GB = Gerda Boyesen; AL = Alexander Lowen. Dotted arrows indicate indirect influences.

For the protagonists in Oslo in 1950, the technical developments they were making were integrated into a vision focused on the notion of psychotherapy. Their work focused on the same clientele as that of the psychiatrists of the day who were psychoanalysts. They considered themselves simply psychotherapists, but ones who explicitly included the psyche in the dynamics of the organism. This new way to approach the individual, fashionable since the work of Kurt Goldstein (1939) on the organism, necessarily opened up a new way to envision psychotherapy. They did not see the necessity to distinguish themselves by calling themselves body psychotherapists. Not all of them considered themselves Reichians. As soon as we admit that the psyche is part of the regulators of the organism, it becomes almost natural to approach the psyche by observing how it relates with the behavioral, bodily, and physiological dimensions.18 They did not oppose body and verbal therapy, because speech is only one of the behaviors of the human organism.

I illustrate this development by taking a few important personalities as an example—mostly Nic Waal and Trygve Braatøy, who introduced Reich’s and Fenichel’s points of view to psychiatric institutions to develop modes of interventions that combine different body and psychotherapeutic methods. I then speak of Gerda Boyesen, who introduced a synthesis of the Fenichel-Reich debate, as well as other Scandinavian approaches, in body psychotherapy. That is why she did not like that I referred to her, in my earlier writings, as a representative of the neo-Reichian movement. Gerda Boyesen synthesized what was said and practiced around her without knowing that her proposition was influenced by the teachings of Fenichel in Oslo when she was twelve years old.

After World War II, we witnessed a kind of trench warfare between the psychiatrists who were psychoanalysts in dominant positions and the movements in psychotherapy breaking away from psychoanalysis, like Jungian analysis and Reichian Vegetotherapy. Oslo is one of the rare places where the discussion between Fenichel and Reich concerning the body in psychotherapy could survive within the academic institutions.

Nic Waal19 (1905-1960) was a psychiatrist who used body-oriented techniques such as Vegetotherapy in a psychiatric institution. She trained in child psychiatry and became a psychoanalyst in the Berlin Institute, where she also joined communist-oriented psychoanalysts such as Otto Fenichel, Wilhelm Reich and Edith Jacobson. She had worked with Reich in the Berlin psychoanalytic clinic. In Oslo, she actively helped Jewish children escape from Nazi persecution. She became the head of the child psychiatry department at Oslo University. In Copenhagen, she trained child psychiatrists in the state hospital and at the university. At the end of her life, she created a Nic Waal Institute, designed to help handicapped children.20

With Ola Raknes, Nic Waal used Vegetotherapy in Gaustad and Ulevaal psychiatric hospitals. They remained in contact with Reich.21 She also undertook clinical research with other colleagues to demonstrate the utility of using body techniques as a form of psychiatric intervention. Like Trygve Braatøy, she collaborated with research projects in Rappaport’s Menninger Clinic, Kansas (USA).22 In Oslo, some of her research attempted to validate the use of the following forms of intervention in psychiatry:

In the Reichian world, Nic Waal is known mostly for the detailed techniques of body analysis that she developed for Vegetotherapists. Recently, Berit Bunkan23 has included Waal’s system in a synthesis of body analysis techniques created in Oslo.

Nic Waal also found ways of using the classical technique of passive movements developed by physiotherapists to analyze the psychological state of patients and their way of relating to their therapists. A passive movement occurs when a therapist moves a segment of the patient’s body. This technique is mostly used to evaluate the state of joints, tendons, and certain reflexes. Arms, legs, or head are moved relatively slowly to observe how respiration responds to this mobilization. Both the patient and the therapist can observe these reactions simultaneously. It is thus easy, as in Reich’s jellyfish exercises, to create a co-conscious experience of the patient’s body responses. The patient’s reactions allow the therapist to generate a form of diagnosis that captures what is happening during the exercise, and the patient can therefore grasp it as well. This type of “local” operational diagnosis is different from the more global forms of diagnoses that were in use in psychiatry in those days. As an example, I describe different responses that are observable when a patient allows the therapist to move his right arm:

Probably influenced by Fenichel’s remarks on hypotone, Nic Waal, like other Norwegian colleagues working in therapies that combine body techniques with psychotherapeutic intentions, included an analysis of hypotone in her work with passive movements: “one does not find resistance, but a characteristic looseness and slackness. It can vary between lazy, dull, ‘dead’ or can be recognized by a strange lightness” (Waal et al., 1976, p. 274). When touched, hypotonic muscles feel gelatinous.

Trygve Braatøy (1904-1953) was born in the Norwegian community of Minneapolis, Minnesota (USA), where his father was a Protestant minister. He studied neurology in Paris and trained as a psychoanalyst in the Berlin Institute, mostly with Fenichel, in the early 1930s. There, he was also influenced by Wilhelm Reich’s psychoanalytic ideas and the Gindlerian discussions on the body. In 1933, he went to Oslo, where he worked as a psychoanalytic psychiatrist in the Ulevaal psychiatric hospital. He was actively engaged in combating Norwegian movements that sympathized with the Nazis by publishing his opinions in the “illegal press.” With Waal, among others, he also helped people running away from occupied Sweden by giving them a diagnosis that justified their hospitalization until it was safe for them to flee.24 In 1954, he published Fundamentals of Psychoanalytic Technique, which is his testament. Fenichel only mentions Braatøy for his psychoanalytic publications on adolescence and schizophrenia.25

In Norway, Trygve Braatøy (1942, 1947, 1948, 1954) tried to develop a way of introducing the body in a psychoanalytic framework that is compatible with Ferenczi and Fenichel’s technical propositions. However, he also agreed with Reich that psychoanalysts should find ways of including some “hands-on” work during psychotherapy. After World War II, there were two main groups of body psychotherapists in Oslo:26

This division lasted for the rest of the century. Fenichel’s group was strengthened when Trygve Braatøy became professor of psychiatry and head of Oslo’s psychiatric institutions in 1945. One reason for his nomination may have been his capacity to integrate the work of Reichians working in these institutions, such as Nic Waal.27 Braatøy saw himself as (a) a practitioner with a broad and humanistic approach to patients with (b) a psychoanalytic specialization. For him, patients were more important than theory. He did not participate in the bitter wars between psychoanalytic clans. He explored ways of associating knowledge on body techniques that was available around him, with a classical but flexible psychoanalytical setting. For example, he analyzed the biomechanical implications of having patients lie on a couch. He made explicit descriptions of the influence of this posture on the mind of patients and their way of communicating with a psychotherapist. He would discuss with patients some of their motor patterns; sometimes he would touch a patient who needed comfort. He also included the analysis of patient breathing patterns in his psychoanalytic work. Although Braatøy acknowledged Reich’s contribution to discussions on the association of body techniques and psychotherapy, he seldom used Vegetotherapy techniques. He preferred other body-mind approaches:28 Ferenczi’s active technique, yoga, or the relaxation methods of Schultz and Edmund Jacobson.

Like Fenichel (1935), Braatøy admired Reich’s Character analysis. He often used it to begin a psychotherapy process. It could help a patient become aware of how he presented himself. The content of the representations was only discussed later. According to Braatøy, it is easier to explore a patient’s anger once he has experienced his ways of controlling it. Braatøy was irritated by Reich’s constant need to seduce everyone and his need to be every one’s boss. After 1933, “he, in his impatience with our slow progress, changed into a trinity of Freud, Einstein, and Wilhelm der Grosse29 and must be read accordingly” (Braatøy, 1954, p. 101).

Braatøy did not have the time to acquire knowledge of physical therapy. He preferred to collaborate with people who had knowledge of the same caliber as Elsa Gindler. According to him, Reich’s Vegetotherapy mixed simplistic body and psychological techniques in an unsophisticated way.30 Vegetotherapists tend to overestimate the need to support emotional expression and underestimate the need to strengthen the patient’s capacity for insight.31 Braatøy thought that if a patient needs to explore himself using body and psychotherapy techniques, he might get a better treatment if he sees a competent physical therapist and a trained psychotherapist who work as a team. To develop a form of body treatment that could be used as a complement to a psychotherapeutic approach, Braatøy collaborated with an impressive Scandinavian orthopedic physiotherapist, Aadel Bülow-Hansen. She developed forms of massage that could be used in a complementary way with a psychoanalytically oriented psychotherapy. Like Fenichel and Reich before him, Braatøy followed the standard practice of not mentioning his team’s body experts. Even Nic Waal does not appear in his references. Like his colleagues, he presents his thoughts and methods as if he had developed them alone.

Although Braatøy had the impression that he was proposing a reasonable way of integrating bodywork in a psychoanalytical process, his synthesis was different from most discussions in psychoanalytic circles. Like other psychoanalysts of his generation, trained in Berlin, he often used notions associated to regulation systems and was less interested by the more fashionable terminology of object-oriented psychoanalysis. He avoided reducing what patients experienced to Freud’s second topographical model or too simplistic sexual metaphors. He was of course familiar with Freudian dichotomies (e.g., narcissism/object relation, id/super-ego, Eros/Thanatos.), but they did not strike him as particularly useful for his work with psychiatric patients. This choice led him to pay particular attention to how individuals, such as a patient and a therapist, auto-regulate and regulate each other. This approach is closer to the one recently developed by psychoanalysts such as Daniel Stern and Beatrice Beebe32 than the one by Melanie Klein.33 Today, for most psychotherapists, the importance of regulation systems is so obvious that the notion is considered standard professional terminology.

Braatøy34 is also prudently interested in Groddeck’s and Reich’s need to make the patient’s negative transference apparent as soon as possible. It is possible that this urge could be a part of their need to charm patients. For Braatøy, it is obvious that at the end of a successful analysis, a patient should be able to speak his mind, but this does not mean that every disagreement in the course of treatment is necessarily resistance. The patient, who is an adult human being, should be able to express resentment and other reactions directly.35 However, by entering too quickly into an analysis of negative transference, the therapist may restrain the patient’s spontaneity and prevent him from discovering that even positive transference may incorporate critical stances, while negative attitudes are always a “part of one’s love” (Braatøy, 1954, p. 304).

Developing a critical form of thinking, respecting one’s ambivalence, and even open resistance to some proposals made by one’s psychotherapist is part of the psychoanalytical process. Learning to integrate such abilities can have “high survival values” (Braatøy, 1954, p. 304).

TRANSFERENCE AND CHARACTER

Laplanche and Pontalis (1967, p. 492) distinguish a general meaning of transference and countertransference from narrower and more specific uses of the terms. The wider meaning designates everything that is experienced by a patient and a therapist for each other. In its narrower meaning, the term transference only designates instances when a patient unconsciously assimilates his therapist into to a scheme constructed with someone else. For example, there is transference when a patient reacts to the therapist with the representations and behaviors he, the patient, developed to deal with his mother. This transference can activate a set of unconscious experiences within the therapist that consists of what he experienced with his own mother. Today, it is well understood that anyone can transfer and countertransfer, even a therapist. The important point is that one person experiences transference, and this triggers a countertransference in another person. The structure of transference is like that of a dream: unconscious material activates preconscious affects and representations. Often, a therapist is aware of the manifest preconscious dimension of his countertransference and forgets that the unconscious is really unconscious. Only during supervision can he become aware of the unconscious dimensions of his counter-transference.

Braatøy mostly used the narrower definition of these terms, because he wanted to differentiate transference from other nonconscious relational dynamics that can also occur during a therapeutic interaction. For example, he wants to differentiate transferential dynamics from projections or the impact of character as clearly as possible. An example of an interaction with a communicative strategy, activated by a character structure is that of a patient who has a characteristic tendency to sulk with everyone. He will therefore also sulk with his therapist. Braatøy tries to experience the impact of this sulking behavior on the way he perceives the patient, and then talk about the impression this habitual behavior has on his way of interacting with the patient. For Braatøy, this form of habitual behavior is a character trait but not transference. Braatøy sometime supported various forms of bodily activity during a session, as these could facilitate the analysis of how a patient deals with others, by default. It is not really transference, because the therapist is not identified to another person. It is the patient’s standardized form of adaptation.

Character traits, like other patterns observed in studies of nonverbal communication, are mostly regulated by nonconscious mechanisms. Only their manifestation can reach consciousness. On the other hand, transferential phenomena are principally regulated by the unconscious dynamics described by psychodynamic models. For example, every time his patient sulked, Braatøy noticed a characteristic tightening of the lips. This is clearly a form of automatic reflex. This reaction may have a history that might be discovered by looking at photographs or films taken by the family and sometimes by interviewing the parents. Braatøy asked his patient to explore this tightness in various ways—exaggerating it, doing the opposite, and so on. It is only a manifestation of transference when there is evidence to show that this tightening expresses an affect that was constructed in the patient’s past within a specific relational scenario.

To summarize, Braatøy thinks that a psychotherapist needs to differentiate at least two types of communication patterns that are triggered by a patient’s habitual way of functioning:

The structure of transference and its analysis is thus more complex than what occurs with character traits. In a study on suicide attempts, carried out with my colleagues of the Laboratory of Affect and Communication (LAC), we37 isolated behaviors that could differentiate the following two groups of patients, all of whom were interviewed by the same psychiatrist:

These behaviors had a systematic impact on their therapists’ nonconscious behavior. The therapist was not aware of (a) the patient’s behaviors that varied in function of suicidal risk, and (b) the impact of these behaviors on her. We then showed our films to the therapist and pointed out the behaviors of the patient and the therapist that varied in function of the patient’s suicidal risk. These behaviors had no apparent meaning for her.38 Nonconscious processes had probably activated the structure of these behaviors. These behaviors are differentiated in function of a diagnosis and may have been generated by organismic regulation systems.39 However, it is highly unlikely that all reattempters had a particular type of transference on the therapist and that all attempters had another common transference.

VEGETATIVE IDENTIFICATION OR ORGANIC TRANSFERENCE

Reich describes yet another form of nonconscious interaction between a patient and a therapist:

The patient’s expressive movements involuntarily bring about an imitation in our own organism. By imitating these movements, we “sense” and understand the expression in ourselves and, consequently, in the patient. When we use the term “character attitude,” what we have in mind is the total expression of an organism. This is literally the same as the total impression that the organism makes on us. (Wilhelm Reich, 1949a, Character Analysis, III.XIV.2, p. 363)

This relational effect was later called vegetative identification.40

Influenced by studies on nonverbal behavior,41 Bjørn Blumenthal assumes that a psychotherapist can only perceive a small part of the complex system that regulates his interaction with a patient.42 Consciousness can only focus on a few, relatively simple, events.43 It is incapable of perceiving something as complex as a set of communication strategies that often co-occur. We therefore need to distinguish the following forms of data management:

There is thus a bottom-up and a top-down interaction that is constantly occurring. This explains why the conscious explanations provided by a therapist or a patient relative to a given set of behaviors (a) does not have the means to propose a robust analysis of what is happening, but (b) may have a form of relevance that cannot be explained by the explicit rational being used.

For example, a patient’s breathing pattern may influence the therapist’s breathing pattern. Most of the time, neither the patient nor the therapist is aware that their way of breathing is under some mutual influence. In group therapy, however, sometimes a third person notices the phenomenon. He may share his impression that the breathing of two persons who are interacting with each other has become shallower, in a coordinated manner. The patient and the therapist may then become aware of a form of interpersonal “resonance”44 between each other’s breathing patterns. Body psychotherapists have thus learned to become aware of such moments. They do not understand how this mutual regulation occurs, but they learn to notice it, as if from the outside. It is a bit like a person who notices that his shirt has a spot on it when he passes in front of a mirror. Some vegetotherapists call this type of mutual quasi-physiological interpersonal regulation vegetative identification. Having learned to notice these forms of physiological interpersonal impacts, the therapist can also become aware of certain fuzzy variables, like the particular atmosphere of a relationship that may correlate with such adaptations. He then tries to specify some characteristics of this atmosphere, like vocal tone, the rhythm of gestures or affects.45 David Boadella regularly stresses that these forms of resonance are a form of contact. They emerge in the background while conscious dynamics are focusing on an explicit content. For example, I may be discussing a dream with a patient, and in the background a kind of sympathy is emerging.

At the end of his life, Braatøy discovered that he could use films to notice such forms of mutual nonconscious adaptation between therapist and patient: adaptations that could not have been noticed otherwise.46 What we are dealing with, in such cases, is a form of automatic coordination of numerous organismic skills situated in different dimensions of the organism (mind, affects, behavior, physiology, body). Jay Stattman (1987) also talks of organic transference. Here is an example:

Vignette on organic transference. A psychotherapist, who is using massage, feels with his hands that his patient’s skin is cold. This therapist has a history in which cold skin has played an important role. The therapist has worked on this issue during his personal psychotherapeutic process. He is aware of how he automatically reacts when his hands contact a certain type of cold skin. However, he cannot prevent his hands from moving in ways that convey anxiety. The therapist decides that with this patient, massage is not a tool that he can use. He has a negative organic transference with this patient. However, the patient responds to this decision as a failure, just like the therapist’s father experienced failure and rejection when his child began to avoid contact with him. The patient wants the massage to continue. He becomes furious when the therapist insists that he wants to continue the therapy with other methods.

This is an example in which the therapist is transferring, while the patient is experiencing a countertransference. In such a situation, vegetative identification and psychodynamic transference are both active. To understand this situation, it is useful to have a working model that allows the therapist and his supervisor to distinguish the different mechanisms involved. The difficulty in this situation is that the patient has an affective countertransference triggered by the therapist’s organic transference.

The psychoanalyst’s automatic fear of “acting out” is a form of rigidity that Braatøy criticizes (Braatøy, 1954, V.4, p. 134). If one assumes that a psychoanalytic cure may influence the dynamics of the organism, one can expect that a patient will develop a more varied and comfortable postural repertoire when the psychotherapy is effective. This modification of the patient’s body dynamics are activated by mechanisms that are different from those on which a physical therapist tends to work.47 When a patient feels better, he needs to explore more comfortable and open ways of expressing himself. For Reich and Braatøy, the phrase “acting out” only applies when the therapist can demonstrate that what the patient is doing is a form of resistance against the therapy. For example, they do not consider that making love with one’s lover during the psychotherapy process is necessarily a form of “acting out.” This analysis is close to Fenichel’s (1945a, p. 246), who thought that sensorimotor inhibition could be a part of a defense that protects a psychological incapacity to integrate an emotion. Less interested by the more cognitive aspects of the psychoanalytic technique, Braatøy sometimes forgets that it is difficult simultaneously to (a) integrate all aspects of a person and (b) focus on the delicate and complex intricacies of thoughts and affects.

Psychoanalysis begins its liberating influence by requiring that the patient lie on a couch. This position was used in hypnosis and in relaxation, and it is recommended because it allows maximum relaxation of all the muscles. It minimizes the pull of gravity on posture. The patient can then breathe more easily, his defense system will relax, and his emotions will enter more easily into the realm of thoughts and behavior.48 The main physiological function of lying on the couch is that this posture supports a process that enhances the coordination among muscles, breathing, guts, and somatic reflexes. “This is the physiological raison d’être of the couch in psychotherapy” (Braatøy, 1954, VI.2-3, p. 169). This process is an efficient way of loosening the defense system that may activate a need to move and change position—precisely the sort of spontaneous behavior a psychotherapist may want to support. In clinical approaches, no rule is absolute. There are always cases in which such a development could be harmful.

Another implication of the standard psychoanalytical setting is that lying on the couch may induce more vulnerability in fragile patients. Today, most psychoanalysts use a similar analysis and recommend that fragile patients (e.g., narcissistic and borderline patients) remain seated during therapy. In this way, the back muscles and the muscular defenses remain mobilized. Others work with fragile patients lying on the couch but personalize the contact by using techniques such as Ajuriaguerra’s relaxation method.49 For psychiatric treatment, Braatøy recommends an adaptation of a basic posture (lying, sitting, standing, etc.) to the therapeutic needs of the moment. Here are a few examples:

What was, in Braatøy’s professional environment, daring psychotherapeutic proposals have become relatively standard in contemporary body psychotherapy. Physiotherapists and osteopaths often notice that their work elicits intense emotional reactions, but they do not have a frame of reference that allows them to deal adequately with such events.53 When Braatøy tried to loosen a jaw, he would use “a firm pressure against the masseter muscles blocking a specific way of conducting the jaw and mouth, or a similar pressure under the chin against persistent tension in the jaw openers” (Braatøy, 1954, V.7, p. 144; VIII.l, p. 235). These interventions, close to the techniques used by Reich in Berlin and Oslo, could release deep respiration and crying, as well as other forms of intense expressions.54 This analysis was confirmed when he analyzed a film of a psychotherapy session given by Paul Roland to a schizophrenic patient.55 Braatøy observed that Roland helped the patient by “gently but firmly stroking his back and neck. He asked the patient at the same time to relax and told him he wanted to help him.” He noted that a key feature of this intervention was that the therapist spoke with a very low voice, moving close to the patient. In that particular case, the therapist’s tone of voice was so soft that the microphones could not record it clearly. Braatøy’s comments about this film mentions that Pavlov had also noticed that when a therapist asked his questions “very softly in very quiet surroundings,” a frightened schizophrenic patient would answer. He made a similar observation when talking to infants. Finally, he quotes a study published in 1885 by Weir Mitchell, showing that softening one’s approach to patients who suffer from anorexia nervosa could also be effective. For Braatøy, it was important to make this point in his textbook for psychoanalysts because it was not the current practice in his day to accommodate one’s behavior to the needs of a patient.

Braatøy found ways of analyzing behavior in a more fluid and precise way than Ferenczi. He is sensitive to small variations of the voice, as when a voice becomes irritating once it becomes high pitched and overeager,56 or when the flow of words becomes particularly rapid. He is attentive to various forms of gazes and to how the patient manages to capture the therapist’s visual attention. Quoting one of Reich’s cases, Braatøy shows that words and gestures may be indicative of different layers of the patient’s character. In such cases, it would be clumsy to attract the patient’s attention to both these phenomena, as the patient may then receive more information than he can handle. Often, a high-pitched voice is a sign of defense against emotions, as when an adult woman absolutely wants to maintain a girlish stance, a “good-little-girl eagerness” (Braatøy, 1954, V.6, p. 141). When a female patient passes from high pitch to a lower pitch and develops a “Marlene Dietrich” kind of voice, it is often because her vocal apparatus has relaxed. “A deeper, more adult voice, results in a radical new sort of feedback from her own behavior. The tone of voice may be of basic importance in changing the patient’s patterns” (Braatøy, 1954, p. 141).

This analysis was often taught by Gerda Boyesen during the 1970s, in her training courses. It is also close to some of Downing’s observations, described in his 1996 book, The Body and the Word. These are but two examples showing that Braatøy already explored techniques that became popular during the second half of the century. Once again, I am not saying that Braatøy is at the origin of Downing’s formulations, as it is by following different routes that Downing arrived at the conclusion that working on the connection between words and gestures in this way is a particularly useful psychotherapeutic method.

BREATHING, TRANSFERENTIAL DYNAMICS, AND YAWNING

Chronic muscular tensions may repress certain forms of emotional expression in a relatively direct way (e.g., when a person tightens the jaws to inhibit a need to shout or cry) or inhibit emotional dynamics in indirect ways (e.g., by reducing breathing motility):57

When such a person practices coitus interruptus, an eager and potent—or non-frigid—person tries to counter an intense sexual excitement with an even more intense holding-back attitude, blocking the panting and the sexual outcry at the height of the acme; that is, his sexual blocking includes an abrupt and intense blocking of respiration. By observing and describing these manifest phenomena, one can connect specific aspects of his sexual behavior with his respiratory tenseness and precordial and shoulder myalgia. (Braatøy, 1954, X.5, p. 326f)

Most psychotherapists, even those who have no training in body dynamics, intuitively perceive that a patient feels better when his breathing becomes more relaxed and variable.58 For Braatøy, breathing is a part of the regulation system that deals with attention and affects. When a person becomes attentive, she often breathes less; when she cries the breathing becomes intense. Influenced by Edmund Jacobson’s progressive relaxation technique,59 Braatøy was particularly interested in spontaneous respiratory changes, as in the following example of an explicit way of working with breathing:

When I work in this way with patients, I continually observe their breathing and always fit the suggestion, “Relax!” to the beginning of expiration. By that, I intend to call forth a summation of the local relaxation of the muscle group we work with and the general relaxation that goes with the expiration. If one does not in this way “dance with the rhythm and relaxation of expiration,” one risks giving the specific suggestion, “Relax!” at a time when the respiratory muscles tense themselves in inspiration. This produces then an interference. (Wolfgang Kohlrausch 1940, quoted in Braatøy, 1954, p. 166)

Gerda Boyesen often taught this method in her training courses during the 1970s. It is close to Gindler’s need to avoid constricted breathing. This same type of analysis may have been introduced in Oslo by Clare Fenichel and Elsa Lindenberg, and/or it may be obvious to any person who knows how to work with the complexity of respiration. This is an example of a technique that Braatøy must have calibrated with experts of bodywork he does not quote.

Braatøy (1954) was also attentive to moments when yawning manifests itself spontaneously, because it can be a “compensatory respiration when opportunity for relaxation arises” (p. 165). In some cases, yawning may become so intense that it will drag “the whole body with it in a global cat-like stretching-yawning movement” (p. 165). When yawning is associated with deep relaxation, it is often accompanied by “rumbling in the abdomen” (p. 169) and stretching.

This is also true for therapists, as attention tends to reduce breathing. The young and eager therapist’s continuous attention may become harmful for him. Thus, professional habits may generate harmful chronic forms of tensions (Blumenthal, 2001). This is another reason why the therapist’s floating attention, recommended by Freud, is beneficial—not only as a way of listening to what the patient is saying but also to the psychotherapist’s own auto-regulation.

One day, Braatøy60 noticed that a patient’s yawning reaction was partially blocked. She had an apparent stretch-and-yawn reaction,61 but the inspiration was weak: “Charles Darwin . . . said that yawning may appear as a symptom of a slight fright. The slight fear induces alert, watchful attention and thereby restricts breathing; but because it is slight, it permits the oxygen need to break through from time to time in yawning” (Braatøy, 1954, p. 167).

SUDDEN SURPRISE, FEAR, AND RELEASE

Braatøy and Bülow-Hansen opposed the startle reflex to the orgastic reflex, as if they formed a polarity. They gradually constructed a new version of the Reichian expansion (healthy)-contraction (unhealthy) opposition. A startle reaction is mostly connected to fear and anxiety, whereas yawning and stretching is manifestly a way of being more comfortable and alive. Like other colleagues, I have integrated in my clinical work this modification of Reich’s rigid way of associating contraction and anxiety.

For Trygve Braatøy, the need to avoid surprise seems to be the nucleus around which a neurotic psychosomatic regulation organizes itself.62 Surprise is then experienced as the risk of losing control and a general feeling of insecurity. At the age when a child’s perception of the world is full of magical notions, the child does not yet have the capacity to master his behavior or hide an expression of surprise when adults display unexpected behaviors. The fear of expressing surprise is particularly strong in a strict environment that does not tolerate uncontrolled childish forms of behavior. Yet children cannot control their behavior when unexpected situations arise.

Gradually, the child develops an anxiety and even a fear of being caught using forms of behavior that adults do not tolerate. He is afraid of not behaving as he should. In such moments of shock, when caught doing what is forbidden, a crucial knot of neurotic regulation is formed. The compulsive neurotic’s stubborn behavior, which persists on all levels, including his doubts and objections, expresses his attempt to control all situations. If he does not control the situation, he may run up against a surprise and then—bang—lose control of himself: “Discussing this attitude on the verbal psychological level, to point out that this is ‘intellectual resistance’ does not get anybody anywhere. The therapist must be able to bring out in a convincing way that it is the bump, the surprise, that the patient is afraid of—and for good reasons!” (Braatøy, 1954, VIII.3, p. 261). This model is useful to explain the behavior of patients who are apparently in control of everything they do, and then suddenly surprise everyone by becoming dispersed and impulsive, often for irrational reasons.

The startle reaction is the prime archaic reaction when a child is surprised doing something that meets the disapproval of others.63 The startle is at first so intense that it mobilizes the whole body. Therefore, the vegetative and body dimensions of neurosis structure themselves around this reflex. At first, the child’s repeated startle response mobilizes many parts of the body. Gradually, the startle reaction tenses those muscles that are most often used to control its expression: the eyes, the neck muscles, reduction of mobility, and of the postural repertoire are involved in the formation of a more detailed description of what Reich called the neurotic armor. This analysis, which combines neurological, body, and psychological dynamics, led Braatøy to recommend to young psychoanalysts that they should learn to become attentive to the following points when they use character analysis:

During such delicate moments, Braatøy uses his model of the startle reflex to guide his interventions. As the startle shortens most extensors, he tries to counter that effect by seeking to activate a pleasurable stretch-yawn reflex and the affective feelings that tend to associate themselves with this reaction (Braatøy, 1954, VI.2-3, p. 168f). In her courses, Gerda Boyesen mentioned that when such an intervention is efficient, the patient would report that he has the impression of melting.

As long as a person stretches without pleasure and without yawning, Braatøy assumes that the startle reaction is still active. Thus, when a patient stretches without pleasure, he can look for already active chronic startle reactions responses. For this, he will use his knowledge of body reading and the patient’s introspective powers. For Braatøy, a startle reflex is the somatic part of a more general fear response that also includes affective and psychological regulators.

Aadel Bulow-Hansen (1906-2001) was a physical therapist trained to use Scandinavian massage techniques for orthopedic purposes. She was also evidently influenced by the psychophysiology of her day, as she adopted a holistic organismic stance developed by researchers such as Walter B. Cannon (1932) and Kurt Goldstein (1939). The colleagues whom she trained in her school are still highly appreciated in Norwegian hospital services.

Bülow-Hansen collaborated with Braatøy from 1947 to 1953 to develop a massage method as a complement to the psychoanalytic treatments proposed by Braatøy and his team. This treatment was developed within a frame compatible with current scientific and clinical knowledge of the time. Its aim was to support freeing the physiological and body dynamic involved in the regulation and inhibition of emotional experience. It aimed at a relaxation state, induced by reducing muscular tensions and increasing the flexibility of breathing patterns in patients who were characterized as particularly rigid (or armored, to use Reich’s terminology).67 As the method developed, it was gradually able to deal with a wider set of symptoms. The treatment was at first called the Braatøy-Bülow-Hansen therapy, and then Psychomotor therapy.68

When Aadel Bülow-Hansen left the psychiatric institutions, she continued to train highly competent physical therapists who, like Berit Heir Bunkan (2003), continued to incorporate this method and its new developments in the Norwegian health system. A third generation of active practitioners is developing the work of Bülow-Hansen in the largest Norwegian towns and institutions. Having participated in a reunion in Oslo in 2005 with presentations given by psychomotor therapists who demonstrated how physiotherapists can become involved in a psychotherapeutic process, I consider it one of the leading massage schools in the world. This was also made possible by therapists who trained in psychology and physiotherapy, like Berit Heir Bunkan and Gerda Boyesen.

The Braatøy-Hansen combination of (a) psychotherapy and (b) bodywork by a team of people specialized in each form of intervention is what I call the Fenichel-Gindler option for body psychotherapy, in opposition to the Reichian option, in which one therapist combines intervention on all of the organismic dimensions. For the moment, only the second option is considered body psychotherapy. However, the Fenichel option is used by many psychiatric services. For example, I have observed it in the Psychosomatic Gynecology and Sexology Unit, in the Geneva Department of Psychiatry, when Willy Pasini directed it in the 1980s.69 The team combined several approaches, such as psychomotricity70 and behavior therapy, in association with a type of psychotherapy based on psychodynamic principles and on the Ajuriaguerra psychodynamic relaxation technique.

Aadel Bülow-Hansen created an efficient way of working on the dissolutions of tensions that participate in the maintenance of a chronic startle reflex. She found ways of detecting muscular tensions and restrictions in breathing that could be associated with such a reflex. This enabled her to describe and define them with more precision. Most of the time, it is not the whole startle mobilization that is activated in a system of chronic tensions, but only “remnants” (M.-L. Boyesen, 1976). Here are examples of techniques used to find these remnants.

Vignette on body reading and startle reflex. The patient lies on his back on a flat firm surface (e.g., a massage table or a couch). Each time there is an empty space, an arch, between a part of the body and the flat surface, analysis begins. The higher the empty space, the more one can suspect shortened extensor muscles that could be associated to a chronic startle reflex. This is most frequently the case under the following parts of the body: neck, shoulders, wrists, shoulder blades, lower back, thigh, knees, ankles, and soles of the feet. The length of an arch (e.g., from hip to shoulder blades) is also a sign of the importance of chronic tensions of the extensors. The suspicion that one is facing a chronic startle reflex increases when these tensions are associated to a mainly thoracic form of breathing. The more the abdominal breathing is inhibited, the more one can suspect fear. A difficulty in having a relaxed deep expiration is also a criterion of the same. Other signs of fear are eyes that are chronically wide open or eyes tensely shut (Brakel, 2006; Hillman et al., 2005).

There are often several possible causes contributing to a body profile. The practitioner who notices such a configuration must then begin an inquiry to ascertain that a chronic startle reflex is present. He may, for example, ask the patient what is experienced when an arch is artificially amplified or reduced. In such cases, I often ask the patient to explore what happens when he coordinates this movement with his breathing (e.g., what happens when he extends the wrist at each expiration).

Separate your lips slightly. Let your lower jaw drop as much as possible. Close your eyes. Slowly tilt your head backwards until it delicately touches the back of the neck. At the same time, gradually open your mouth as much as possible “as if to swallow a peach.”

You are yawning. That is the aim of the exercise. . . .

N.B. yawning is the most efficient cure for nervous tension and fatigue. (Wespin, 1973, on tai chi, p. 60; translated by Marcel Duclos)

In collaboration with Braatøy, Bülow-Hansen developed methods that stimulate the pleasure of yawing and stretching oneself out of one’s shell of fear: “If you did not feel like stretching, then try another way of releasing respiration and the stretch impulses: wriggle your jaw from side to side, spread your fingers and toes and move your tongue around” (Thornquist and Bunkan, 1991, p. 79).

Bülow-Hansen also welcomes sighs and farts.71 The aim is to lower the inhibition of the vegetative dynamics of the affects and strengthen their capacity to participate in organismic regulations during an interaction. In other words, these methods attempt to help people experience themselves as an emotional and sexualized being with vegetative needs. When a patient expresses affective arousal during a psychomotor session, the physiotherapist steps back and supports whatever forms of expressions that need to become manifest. For Bülow-Hansen, the psychotherapist is the one who may propose interpretations of the emerging process and help the patient manage whatever complications arise in his mind and his environments. This technical point may seem trivial to some, but it often happens that I must repeatedly emphasize it during supervision. Those who use massage as a way of strengthening affective dynamics often find it difficult not to become psychotherapeutic. The basic rule, in such cases, is to allow affects to appear in the room but resist the urge to provide an interpretation or solicit its expression. Being aware of such limitations is a way of not strengthening emerging transferential processes. As soon as a psychomotor therapist goes beyond this frame, he often finds himself involved in relational dynamics that neither he nor his patients know how to manage (Thornquist and Bunkan, 1991, 9, p. 116f).

A useful ritual is to let a patient alone for a while at the end of each session to decompress. If ever the libido pressure becomes stronger than can be handled in such a setting, the therapists trained in Biodynamic Psychology will say that it is time to employ the decompression ritual and leave the patient alone so that he can regulate his sexuality privately. I do not know how psychomotor therapists manage such moments, which are not frequent but nonetheless exist. The aim of such treatments is to help a patient express the released emotional and libidinous impulses outside of the massage sessions. These issues can be processed in psychotherapy sessions if they become problematic. When such events repeat themselves during massage sessions, massage is not presently a recommended approach for this patient.

For Braatøy and Bülow-Hansen, Reich’s use of cosmic energy made no sense. The only bioenergy that exists for them is that produced by metabolic biochemical processes. Body sensations, like circulating warmth, can always be explained by mechanisms such as the dynamics of body fluids (e.g., cardiovascular system). Even when there is no adequate explanation for such a sensation, this does not imply that a reference to cosmic energy is relevant or useful. Many sensations that are activated by a breathing exercise, associated by Reichians to orgone, can be more easily understood as the activated metabolic dynamic consequences of internal breathing. This analysis is the same as that proposed by body psychotherapists such as Downing (1996,1.4).

Bülow-Hansen believed that a treatment only acquires a lasting effect if the masseur integrates the symptomatic part of the body in the global postural dynamics. When one focuses on a scoliosis, one should also take into account the fact that this symptom creates disturbances in the global alignment of the body. When a masseur works on the tensions that maintain a scoliosis, he also influences the muscular dorsal chains, from head to toe.72 This is why Aadel Bülow-Hansen taught her pupils to always massage the whole body and integrate in each session some direct work on the symptomatic part of the body that justifies the session. This principle, which was followed by Gerda Boyesen and adopted by her students, is different from the Reichian tendency to focus on a single body block during several sessions.

Vignette on a massage demonstration given by Bülow-Hansen.73 Bülow-Hansen’s way of dealing with the “whole body” is not necessarily that of dealing with every muscle. She tackles a general postural issue and analyzes a muscular chain from several angles, focusing on key points. In the case of a woman who could not touch her feet, she massages the muscles behind the legs, some muscles of the belly, and then the throat. She then coordinates the massage of the throat with the breathing behavior of the upper half of the thoracic cage. From that point, she supports the abdominal breathing. Having loosened the muscular chain and the corresponding breathing pattern, she asks the patient to explore how her belly muscles and breathing are integrated when she tries to bend her body again. Finally, she discusses with the patient what she experiences when the patient stands. For example, she asks the patient to become aware of how the tone of certain body parts is integrated in the global posture.

This technique emphasizes connections between different parts of the body and tries to avoid the impression that the body is a construction of disconnected parts. Body reading is usually conducted with the patient standing, so that the connection between body parts can be situated in relation to the pressure of gravity. This strategy helps the therapist be clearly aware that loosening one part of the body may create tensions in other parts.74 Sometimes a tension may move from an easily accessible part, situated on the surface of the body (e.g., the shoulders), to a less accessible part (e.g., the diaphragm or the psoas). This must be avoided, for one would then be creating a greater problem than the one the patient originally presented. A typical example is that of a patient who is submitted to a painful muscular massage. The masseur may soften the original tension, but to bear the pain of the massage, the patient may have tensed other parts of the body (sometimes most of the body). In the 1970s, Gerda Boyesen regularly used this argument in her criticism of methods developed in the United States, such as Orgonomy, Rolfing, and Bioenergetics.

A holistic approach to body tensions, such as the ones proposed by Rolfing and Bülow-Hansen’s method, often creates a modification of postural dynamics and therefore of the body’s alignment in the field of gravity.75 The neck, back, and legs may become longer, the shoulder may move backward, and the feet may then need bigger shoes. These modifications are not only muscular. They also influence the fascia76 and postural sensorimotor circuits. Technically, this means that the physiotherapist will focus on how the tone of several muscles interacts, rather than on a single muscle.77 For example, Bülow-Hansen focused on the capacity muscles have to not only initiate movement but also inhibit them.78

Aadel Bülow-Hansen often observed how a body movement or a behavior (even verbal) interacts with vegetative dynamics.79 Breathing is the most visible part of vegetative dynamics. An individual’s breathing pattern can vary at any moment in a visible way. These modifications influence the rhythm, amplitude, and shape of external breathing patterns. If the patient has a rapid shallow breathing movement at the beginning of a session, the therapist can observe if his interventions have an impact that creates an even stronger inhibition of the breathing pattern, or on the contrary, creates more amplitude (a) in the thorax, belly, or diaphragm; and (b) mostly on the front, side, or back of the torso. At each moment, the therapist can modify his way of touching, in support of these modifications of the breathing pattern, and thus learn what helps a person or frightens her. Some therapists (like Gerald Kogan and Jay Stattman, trained in Gestalt therapy), modify their verbal interventions in function of such modifications.

According to Thornquist and Bunkan, Braatøy distinguished “breathing in fear” and “breathing to prevent fear” in his work on the startle reflex:

The person who is “breathing to prevent the fear” who does not accept his feelings, has a breathing pattern characterized by active use of muscles and steering throughout the respiratory cycle. There is no exchange between tension and relaxation; there is constant, if varying muscular control. Breathing is restrained. Respiratory movement is mainly abdominal. In this “stomach breathing”, expansion takes place in the sagittal plane only. Respiratory frequency is low with an even rhythm. The pause at the end of expiration is longer than normal, and there is little ability to adapt to either physical or psychological stress. Breathing does not change spontaneously but is controlled the whole time. This way of breathing shows that feelings are shut off. Fear is held outside the consciousness and is not allowed in the open to become an experience.

The person who is “breathing in fear” has superficial rapid respiration. Movement is taking place primarily in the upper chest, with neck and shoulder muscles taking an active part in the work of respiration. Breathing is rapid and often uneven. This way of breathing tells us that this person is in contact with and experiences fear. (Thornquist and Bunkan 1991, 3, p. 25)

Some of Aadel Bülow-Hansen’s pupils further developed her work in collaboration with body psychotherapists. Lillemor Johnsen (1976a, 1976b, 1979) has taught her work to founders of the Danish body psychotherapy school called Bodynamic (MacNaughton, 2004). Their work has been widespread in the United States by therapists such as Peter Levine (2004) and Babette Rothschild (2000), who have developed particularly efficient ways of working with trauma using body psychotherapy techniques. Gerda Boyesen is another pupil of Bülow-Hansen who integrated psychomotoric work in body psychotherapy. (I say more about her work in the following sections.)

Gerda Boyesen (1922-2005)80 is often acclaimed as one of the important European body psychotherapist of the 1970s. Roz Carroll presents her as “the mother of body psychotherapy” (Carroll, 2002, p. 87). Although she mostly focused on the vegetative dynamics and how they are experienced, she approached the phenomenon from several points of view, developed in psychology, physiotherapy, and schools of spirituality. This type of synthesis is not only a good example of the theories in body psychotherapy that emerged in the 1970s, but also an example of why it so difficult to characterize this discipline.

She first trained as clinical psychologist in Oslo in the late 1940s. She then worked in psychiatric institutions that were still influenced by Trygve Braatøy. The content of the courses she followed can be situated somewhere between Freud and Jung, Pavlov and Cannon. Boyesen was manifestly interested by some psychological dynamics, but not in psychology as a field. For example, she was not interested in the issues raised by cognitive psychology pertaining to the dynamics of representations. The only aspect of Piaget’s theory that might have interested her was the idea that children learn most efficiently when they can become active, playful participants in their learning process. On the other hand, she was constantly working with an individual’s capacity to visualize body sensations and situations. This interest kept her close to the techniques of Jungian dream analysis and Gestalt therapy. In her classes, she often mentioned Freud’s two topical models, but she did so in a rather simplistic way. She began her career as a clinical psychologist in psychiatric institutions.

Ola Raknes was Gerda Boyesen’s principal psychotherapist. At the first session, he asked her to say a few words about her life history; then he asked her to explore Reich’s jellyfish exercise:81

Then it was breathing: imagine you are a jellyfish. Moreover, it is with this simple proposal that the dynamic began. Imagine you are a jellyfish . . . let movement and breathing move freely. . . . I had read books on psychoanalysis, but I had never imagined that a psychotherapy treatment could become something like that. I thus let my body move with my breathing: as I exhaled, my head would advance forward, and my chest would sink. It was a pulsation movement of the whole body. An extremely intense dynamic process began. (Gerda Boyesen, 1985a, 1.2, p. 161; translated by Michael Heller)

Raknes had an ambivalent relationship with Boyesen. He never recognized her as fully trained in the Reichian method he taught; however, when he left London, he asked her to replace him in his English practice. After this relatively psychological phase of her life, she focused on the vegetative dimensions of affective dynamics.

Fascinated by Reich’s proposal, she remembered a conference given by Braatøy in 1947, when she was a student.82 During this conference, he said that to become a vegetotherapist, one had to be a medical doctor or at least trained in physiotherapy. It is impossible to become a body psychotherapist without having a good understanding of how a body functions. Because she did not have the courage to begin medical studies at her age, she trained in physiotherapy and chose the Bülow-Hansen Institute for her specialization in this domain. Bülow-Hansen required therapy of the students in her method of training; Boyesen received psychomotor treatment. During this process she acquired deep experiences of what Reich called the vegetative process. Bülow-Hansen’s work on her activated powerful emotional and bodily mobilizations and discharges. This experience was crucial. She not only received an excellent training in physiotherapy, she also felt an urge to explore and understand the vegetative dynamics of the self. She associated these dynamics with various theories of life energy such as Reich’s Orgonomy taught by Raknes. One of the reasons Gerda Boyesen became so famous is that she spent her life transmitting to others her hypnotic fascination for the vegetative dimensions of affective experience. For her, as for Lowen, identity is rooted in these vegetative dynamics. Influenced by other Scandinavian teachers, Boyesen also integrated work on the fluids of the organism, mostly venous blood and the moisture of the skin. She talks of “energetic fluids,” where, in Cannon’s style, I would be content with “biologically regulated fluids.”