General Douglas MacArthur was the most brilliant, most important, and most valuable military leader in American history—at least that’s what Douglas MacArthur thought. When asked by a proper British gentlewoman if he had ever met the famous general, Dwight D. Eisenhower—himself about to march into history—supposedly replied, “Not only have I met him, ma’am; I studied dramatics under him for five years in Washington and four years in the Philippines.”1

MacArthur owed his escape from the Philippines to navy PT boats, but that did not stop the general from questioning the veracity of the navy in coming to his aid or from placing the blame for the eventual fall of the islands at the navy’s door. “The Navy, being unable to maintain our supply lines,” MacArthur wrote in his memoirs, “deprived us of the maintenance, the munitions, the bombs and fuel and other necessities to operate our air arm.”

Conveniently overlooking the fact that his planes were caught sitting on the ground nine hours after the Pearl Harbor attack, MacArthur went on to assert, “The stroke at Pearl Harbor not only damaged our Pacific Fleet, but destroyed any possibility of future Philippine air power.” Still, MacArthur jabbed, “a serious naval effort might well have saved the Philippines, and stopped the Japanese drive to the south and east.”2

At his new headquarters in Melbourne, Australia, MacArthur granted Time correspondent Theodore H. White an interview and “managed to denounce all at once, and with equal gusto and abandon,” Franklin Roosevelt, George Marshall, Harry Luce (Time’s publisher), and the U.S. Navy. “White,” MacArthur lectured, “the best navy in the world is the Japanese navy. A first-class navy. Then comes the British Navy. The U.S. Navy is a fourth-class navy, not even as good as the Italian navy.”3

With such personalities at play, it was no surprise that sometimes the navy thought it was fighting MacArthur as much as the Japanese. Ernest J. King, himself of no small ego, questioned MacArthur’s views from the start, and while Admiral King enjoyed a momentary sigh of relief after the Battle of Midway, he was still livid at comments General MacArthur had made on the eve of the Battle of the Coral Sea one month before. MacArthur had warned newspapers that a major Japanese invasion fleet was bearing down on Port Moresby and possibly even Australia. Let them come, scolded King, but under no circumstances let the Japanese know we know they’re coming! To do so raised a huge flag that the Americans had succeeded in breaking the Japanese naval code.

The entire issue of American intelligence being able to read the Japanese naval code with increasing precision was a heavily guarded secret. This effort had been under way prior to Pearl Harbor, and later the intelligence had greatly aided Nimitz in making fleet deployments at Coral Sea and in particular at Midway. King strongly preferred to say as little as possible about the outcomes of these battles—positive though they were—and even less about the navy’s ability to prepare for them by reading coded intercepts.

But on the morning of Sunday, June 7, 1942—when few details of the Midway battle were known publicly—the Washington Times-Herald ran an article asserting that the Americans had known in advance that the Japanese were targeting Midway, as well as Dutch Harbor in the Aleutians. King was furious, but General Marshall was even more so. Marshall had already encouraged King to “treat the operation as a normal rather than an extraordinary effort” and to downplay for the press any spectacular intelligence success. After Marshall saw the Times-Herald on Sunday morning, he fired off a two-page memo to King, urging, “the way to handle this thing is for you to have an immediate press conference” and then practically scripting King’s remarks at the same. “I am strongly of the opinion that this should be done today,” Marshall admonished. King clearly agreed and called an unusual 5:00 p.m. Sunday press conference in his office to deal with the matter largely along the lines that Marshall had suggested.4

Recognizing the goal of news outlets “to acquaint the public in detail with news of action with the enemy at the earliest practicable date,” King nonetheless professed his very firm feeling “that military considerations outweigh the satisfying of a very natural and proper curiosity.” Then, taking Marshall’s advice and downplaying the existence of any specific intelligence pipeline, the admiral launched into a folksy description worthy of FDR, saying that military intelligence was like the piecing together of a jigsaw puzzle and that after Coral Sea, the pieces just fell into place. “Looking at the map,” King opined, “anybody could see that among our various important outposts, Dutch Harbor and Midway offered [the Japanese] the best chance of an action… with some hope of success.” Thus, U.S. naval forces were providentially placed off Midway to counter the strike.

But then King went off the record and zeroed in on the Washington Times-Herald. By publishing “an item which purported to be a ‘chapter and verse’ recital of the composition and functions of Japanese forces advancing toward Midway,” King lectured, the Times-Herald had compromised “a vital and secret source of information, which will henceforth be closed to us. The military consequences are so obvious that I do not need to dwell on them—nor to request you to be on your guard against, even inadvertently, being a party to any disclosure which will give ‘aid and comfort’ to the enemy.” The room was silent.

King then opened the press conference to questions, acknowledging to nervous chuckles that he didn’t guarantee he would answer them. A number dealt with the Japanese thrust against Alaska, bombing Dutch Harbor and invading the islands of Kiska and Attu. King again tried to downplay what was in fact the first direct invasion of American territory in North America since the War of 1812. Not wanting to be diverted from the South Pacific, King assured the reporters that “even the seizure and occupation of Dutch Harbor [which did not happen] is not a determining factor in the conduct of the war… [and that] until they have got to Kodiak I feel they have done nothing momentous. Our pride will be hurt, yes, but we have enough to go around.”

Then King repeated the doctrine of taking calculated risks with concentrated forces that Nimitz had just employed at Coral Sea and Midway. “Don’t forget the proposition,” the admiral told the reporters, “that the minute you try to be strong everywhere, you have only the men available—it means you will be weak everywhere.” Asked in conclusion if the admiral intended to hold regular press conferences, King replied, “No, indeed.”5

What King did intend to do—even as Roosevelt sent him to Great Britain with Marshall to hammer out the broader Allied strategy—was to take one of those calculated risks in the South Pacific and jab back at the Japanese. On one level, this was in keeping with King’s announced policy of going on the offensive as rapidly as possible, but on another, the Allies were left with little choice if they were to preserve the West Coast–Australia lifeline that King had proclaimed as sacrosanct.

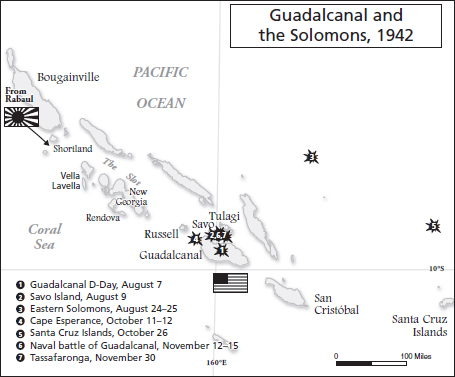

The problem was that despite their setback at Coral Sea, the Japanese were consolidating their hold on the Solomon Islands. If they succeeded in establishing strong airfields there, this airpower would threaten the heart of the West Coast–Australia sea-lanes running past the New Hebrides and Ellice Islands and New Caledonia. Once fortified in the Solomons, the Japanese might well attack these outposts or even New Caledonia itself and disrupt if not sever the link. When the Japanese began to construct a seaplane base on the tiny island of Tulagi, just north of Guadalcanal, in May 1942, King knew that such action required an immediate Allied response.

General MacArthur’s solution right after the Midway victory was to boast that if given the First Marine Division and two carriers with appropriate escorts, he would add three army divisions under his command and attack the main Japanese base at Rabaul in the Bismarck Archipelago, about a thousand miles west of Guadalcanal. King and Nimitz looked at the map and were appalled—not so much by MacArthur’s audacity, but by his total lack of regard for what might happen to the navy’s precious few carriers. They would be put into the center of poorly charted, reef-strewn waters that were surrounded by a complex of Japanese bases, from which would come waves upon waves of land-based aircraft.

A strike at Rabaul was clearly premature, and King advocated approaching the stronghold through a series of island conquests starting in the Solomons. Not only would this begin an advance on Rabaul and launch King’s cherished offensive strategy, but most important to the immediate situation, it would stop the Japanese sweep through the Solomons and safeguard the lifeline to Australia.

King argued that the new seaplane base at Tulagi had to be captured in a matter of weeks. But General Marshall and the army didn’t concur and wanted to postpone any invasion of the Solomons three to four months, “when we would be in a better situation.” King snorted and supposedly replied, “If we were to wait until that time, every exact button of their gaiters would be buttoned up.”6

So as soon as the Midway outcome became clear, King pushed ahead with his plan, asking Marshall, “When will the time be ripe since we have just defeated a major part of the ‘enemy’s’ fleet?” Nimitz, who was always the loyal subordinate whenever King issued a direct order, professed eagerness to get on with it. By contrast, Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley, who had immediate command of the South Pacific Area, pleaded for “more time and more ships, planes, and troops and also supplies and munitions, etc. just as the J.C.S. had,” which, King recalled, “I didn’t like.”7

Part of Marshall’s reluctance was that unlike King with Nimitz, Marshall did not have a willing subordinate in that part of the world. George Marshall had been only a long-term colonel when Douglas MacArthur had served as army chief of staff during the 1930s. Thanks to MacArthur’s own press releases, the public sang his praises and Marshall more often than not cajoled MacArthur in the desired direction rather than issued him direct orders. Now MacArthur stormed to Marshall that the navy was making every effort to subordinate the army’s role in the Pacific. Never mind Rabaul; if there was to be an invasion of the Solomons, he, Douglas MacArthur, must be in command of it.

One can almost hear the hawklike Ernie King laugh in reply. There was no way, short of the eternal fires, that King was going to turn over command of major naval vessels and marines to MacArthur—or any other soldier—particularly in the first major offensive of the war. Marshall and MacArthur further complicated matters by evidencing in memos their shortcomings in understanding command and control for ship deployments and amphibious operations.

King had agreed to the wisdom of an army officer having supreme command (“unity of command” was the catchphrase) of theater operations in Europe, where most of the fighting was to be on land. After some heated discussions, Marshall was forced to acknowledge that there was little he could do but acquiesce to the reverse in the South Pacific, where so many of the operations were to be on or near water. King later described these discussions as having “to ‘educate’ the Army people.”8

When MacArthur squinted at the line along 160° east longitude dividing MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area from Ghormley’s South Pacific Area and found it bisecting Guadalcanal, he still insisted on command of any operation there. King and Marshall solved that problem by simply moving the dividing line west 1 degree of longitude (about seventy miles near the equator) and left Guadalcanal entirely in Ghormley’s theater of operations. (MacArthur would soon have his hands full, as contemporaneous with their move to secure Guadalcanal, the Japanese also launched an overland attack on Port Moresby from Buna, across the rugged Owen Stanley Range.)

With the row over Guadalcanal settled, King hurried to San Francisco to meet with Nimitz to review the details of the planned operation. Nimitz almost didn’t get there. Leaving Pearl Harbor with his immediate aides, he flew east on a four-engine flying boat. This airplane was a one-of-a-kind prototype built by Sikorsky in 1935 to win a navy contract that eventually went to Consolidated Aircraft for the PB2Y Coronado. The Sikorsky XPBS-1 could accommodate forty passengers on short hops, but it was outfitted with sixteen bunks for the 2,500-mile, 15-hour trip—at about 160 miles per hour—between Honolulu and Naval Air Station Alameda, just north of San Francisco.

As the plane made its approach into Alameda, Nimitz and Captain Lynde D. McCormick were ready in their blues for the reception, but busy playing a last game of cribbage. Commander Preston V. Mercer, the admiral’s flag secretary, sat by the window cradling an all-important briefcase containing the after-action report from the Battle of Midway for King. Others in the cabin were relief pilots, crew members, and an officer bumming a ride to a new stateside assignment. As the plane neared its splashdown, Mercer suddenly mumbled, “Oh-oh!”

The big flying boat hit the water a little down in the nose, but the cause of Mercer’s concern was debris floating in the landing area. The plane immediately struck a piling the size of a telegraph pole. Its bow shot skyward, the plane flipped over onto its back, and the fuselage cracked in half. As passengers scrambled out a freight hatch onto what moments before had been the underside of a wing, Mercer anxiously asked Nimitz his condition. “I’m all right,” muttered the admiral, “but for God’s sake save that briefcase.”

McCormick and the other passengers weren’t as lucky. McCormick suffered head lacerations and two cracked vertebrae. Everyone else had at least one broken bone, and the copilot, twenty-nine-year-old Lieutenant Thomas M. Roscoe of Oakland, California, was killed. As crash boats and navy corpsmen arrived, Nimitz, despite his share of bumps and bruises, insisted on remaining on the sinking wing while there were still men inside the plane. Each time a corpsman draped a blanket around the admiral’s shoulders, he promptly removed it and wrapped it around an injured man.

Concerned for those around him, Nimitz kept avoiding the hands that attempted to steer him off the wing and into a crash boat. Finally, an eighteen-year-old seaman second class lost patience with the white-haired gentleman, and knowing neither his identity nor his rank, he shouted out, “Commander, if you would only get the hell out of the way, maybe we could get something done around here.” Nimitz merely nodded and finally clambered into the waiting boat.

Draped with a blanket that this time stayed around his shoulders, Nimitz stood up to survey the scene as the boat backed away from the wreckage. “Sit down, you!” yelled the angry coxswain. Nimitz again obeyed, and in doing so caused the blanket to fall, revealing his uniform sleeve. Seeing the rows of gold braid, the coxswain tried to stammer an apology, but Nimitz cut him short. “Stick to your guns, sailor,” the four-star admiral replied. “You were quite right.”9

Reportedly, a strong tailwind had sped the airplane along to arrive well ahead of schedule, and the naval air station crew had been lax in monitoring the landing zone. Nimitz took the accident in stride and even got to spend a couple of days recuperating with Catherine, who was living in temporary quarters—as were so many military wives—at the Hotel Durant in Berkeley.

King, who had almost lost his valued commander in chief, Pacific, took a different view. He circulated a memo to all commands, demanding more vigilance in the “Policing of Seaplane Landing and Take-off Areas.” King included paragraphs from the official report and concluded that the extracts, “representing as they do a case of ‘it did happen here’ are forwarded as being illustrative of what may be expected when those duties are neglected.”10

Finally, after King’s delays with Marshall and Nimitz’s near-disaster landing, the two admirals met at the St. Francis hotel for their second face-to-face meeting of the war. There was much to discuss about the Solomons operation, but King was his usual expansive self in looking far ahead. He sketched out the long-range, next phase of operations against Japan by outlining an advance directly west across the Central Pacific via Truk, Guam, and Saipan once the initial drive through the Solomons and New Guinea had secured the southern flank. Later, MacArthur would have plenty to say about this strategy.

But meanwhile, King and Nimitz had received intelligence reports that Japanese construction battalions had landed on Guadalcanal and were busy constructing an airfield. King now ordered that both Tulagi and Guadalcanal had to be captured before any Japanese airfield became operational on the latter—quite possibly within the month.

The clock was ticking, and King picked an assault date of no later than August 1, 1942. Everything was in short supply. There was a frantic rush of men and materiel, coordination between ship and shore commands was still in its infancy, and even the veteran First Marine Division had yet to make an amphibious landing under enemy fire. But in all instances, it was a situation where the best training might well come by doing the real thing.

Ostensibly, Vice Admiral Ghormley was in overall command of the operation as commander in chief, South Pacific. With Bill Halsey still in Virginia recuperating from dermatitis, Frank Jack Fletcher, newly promoted to vice admiral, would command three carrier task forces centered around Enterprise, indefatigable as always; Wasp, newly arrived from the Atlantic; and Saratoga, back in action after torpedo damage the previous January. Nimitz had finally succeeded in getting Fletcher his third star despite King’s continued ambivalence.

Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, an attendee at the King-Nimitz conference and recently King’s chief of the War Plans Division, was to command the amphibious forces. Turner had a tough-as-nails reputation and in temperament usually deserved his nickname “Terrible.” Marine Major General Alexander Archer “Archie” Vandegrift led the reinforced First Marine Division and would assume command of the ground forces.

A week after the King-Nimitz conference, Ghormley flew from his temporary headquarters in Auckland, New Zealand, to confer with General MacArthur in Australia and coordinate MacArthur’s operations in defense of Port Moresby with the attack on the Solomons. Not much came of the meeting except for Ghormley to get a case of “the slows” from MacArthur. MacArthur had talked brashly about attacking the stronghold of Rabaul, but now he wanted to delay the Guadalcanal and Tulagi landings—code-named Watchtower—until greater Allied strength could be marshaled.

When King heard this, his opinion of MacArthur sank lower, taking Ghormley’s down a notch with it. Only two weeks earlier, MacArthur had been all for charging into Rabaul, King raved to Marshall, but now, when “confronted with the concrete aspects of the task, he… feels he not only cannot undertake this extended operation [Rabaul] but not even the Tulagi operation.” King’s only concession was begrudgingly to grant Ghormley a one-week reprieve and move D-day back one week to August 7.11

So, on this new schedule, the first of sixteen thousand marines splashed ashore to moderate resistance on Tulagi and initial light resistance on Guadalcanal, succeeding in capturing the uncompleted airfield, soon renamed Henderson Field, on D-day plus one. Fletcher’s three carrier groups paraded south of the island, providing air cover. But by late afternoon of that same day, August 8, Fletcher asked Ghormley for permission to withdraw his carriers farther southward, citing a need to refuel and concerns about a presumed Japanese counterattack. Ghormley replied in the affirmative very early on the morning of August 9, and at 4:30 a.m., Fletcher led his carriers southward toward a refueling rendezvous.

Turner, Vandegrift, and many sailors and marines left on or near the Guadalcanal beachhead would later claim that Fletcher deserted them. In fact, Fletcher had told Turner and Ghormley while planning the operation that he intended to remain on station off Guadalcanal with his carriers only two to three days after the landings. Nimitz, too, in the initial planning of the invasion after his early July meeting with King, had envisioned only “about three days” of close-in carrier support off Guadalcanal.12

A large part of the angst at Guadalcanal came from an unexpected and ferocious battle between cruisers and destroyers that occurred in the wee hours of August 9 around Savo Island, at the western entrance to the sound between Tulagi and Guadalcanal. A substantial force of one Australian and four American heavy cruisers and four destroyers had been positioned to plug the approaches to what became known as Ironbottom Sound in order to protect the transports and cargo ships unloading at the beachheads.

The feared attack came, but the Allied ships reacted slowly and suffered great losses against a lightning assault by five Japanese heavy cruisers and two light cruisers. The Australian Canberra and three American cruisers—Astoria, Vincennes, and Quincy—sank with considerable loss of life, while the Chicago took a torpedo in the bow and two destroyers also were damaged. It was “the severest defeat in battle ever suffered by the U.S. Navy.”13

The only good news was that the Japanese cruisers had circled Savo Island and returned westward rather than pushing east and attacking the undefended transports off the beachheads. But the naval losses were so great—six ships and upwards of a thousand men—that King’s duty officer woke him in the middle of the night when the news finally reached Washington. King read the dispatch several times before asking that it be decoded again in hopes that there was an error. But the news was correct, and King called it “the blackest day of the war,” not to mention a clear setback for his policy of attack, attack, attack.14

Characteristically, Nimitz’s first reaction was calmly to rally his subordinates. Radio communications with Ghormley were wretched and were equally so among Ghormley’s commands. Adding to Nimitz’s confusion was the fact that the Japanese had changed their naval code. He was getting little information from his forces, little insight from Japanese code intercepts, and a steady stream of queries from King as to what was happening. As late as August 19, with Turner’s amphibious ships back in New Caledonia and sixteen thousand marines temporarily isolated on Guadalcanal and Tulagi, Nimitz could send King little more information than “our losses were heavy and there is still no explanation of why. The enemy seems to have suffered little or no damage.”15

Meanwhile, Japanese destroyers had landed nine hundred troops near the American beachhead on Guadalcanal. Turner desperately directed reinforcements of his own to the island, particularly marine fighters to the hurriedly completed airstrip at Henderson Field. Fletcher maneuvered his carriers out of range of Japanese land-based aircraft, but close enough to counter any assault by a major Japanese carrier force that was rumored to be forming at Truk, fifteen hundred miles to the north-northwest. The most nagging question was, when might an attack come?

Through this uncertainty, Fletcher began to rotate his three carrier groups one at a time to the south to refuel as conditions permitted. When aerial reconnaissance and radio intercepts seemed to indicate no immediate Japanese threat from Truk, Fletcher dispatched the Wasp group south to refuel, only to learn that a major Japanese force with the repaired Coral Sea carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku, the light carrier Ryujo, and substantial surface ships was bearing down on the eastern end of the Solomons.

Enterprise and Saratoga steamed to engage, and their planes sank the Ryujo before a counterstrike from the main Japanese carriers severely damaged Enterprise. The “Big E” made for Pearl Harbor under its own steam, but a week later, a Japanese submarine torpedoed Fletcher’s flagship, Saratoga, and this carrier, too, was forced to limp to Pearl Harbor for repairs. That left Wasp and Hornet, the latter already en route south before the Enterprise was damaged, as the only two American carriers operational in the entire Pacific. Fletcher returned to Pearl Harbor with Saratoga, while Rear Admiral Leigh Noyes assumed Fletcher’s carrier command.

Once again, the Japanese had been beaten back, though with tough American losses. Some, particularly in hindsight, seized on Fletcher’s untimely refueling of the Wasp task force as evidence of his incompetence. If three American carriers had been on station and the right intelligence had been received, Fletcher’s fleet would have outnumbered the Japanese and perhaps won another battle of the proportions of Midway.

At the very least, King was again certain that Fletcher should have used his destroyers to make a surface attack against the Japanese, even as Fletcher withdrew his own carriers. Though a strong proponent of airpower, King was also always urging more aggressive surface actions. Barely had the Saratoga recovered its planes when Fletcher collapsed into a chair on its flag bridge and remarked to his staff, “Boys, I’m going to get two dispatches tonight, one from Admiral Nimitz telling me what a wonderful job we did, and one from King saying, ‘Why in hell didn’t you use your destroyers and make torpedo attacks?’ and by God, they’ll both be right.”16

When Saratoga reached Pearl Harbor, Nimitz promptly gave Fletcher, who had been slightly hurt in the carrier’s torpedoing, a much-needed leave. Nimitz continued to feel that Fletcher had acquitted himself well and quite likely would have kept him in the heat of the Pacific action. King continued to feel quite differently. He had never forgiven Fletcher for the loss of Lexington at Coral Sea or Yorktown at Midway, and now there was the appearance—warranted or not—of Fletcher’s having abandoned the Guadalcanal beachhead and misjudged his carrier deployments at what came to be known as the Battle of the Eastern Solomons.

Frank Jack Fletcher would subsequently be portrayed by a long list of military historians as somewhat bumbling and inept, preoccupied with refueling operations, and reluctant to risk his carriers for a knockout punch. Nimitz stood by Fletcher, particularly after Coral Sea, but King seems to have lacked confidence in him from the start. But whatever his perceived shortcomings and less-than-generous press, Fletcher was at the center of the three great naval battles that stopped the Japanese advance in 1942 and turned the tide of the war in the Pacific. Yes, he lost King’s beloved Lexington and the Yorktown, but in exchange he sent six Japanese carriers to the bottom. Fletcher, because of the gentleman sailor he was, would serve without complaint or any subsequent attempt at vindication.

Fletcher was exiled to command the Thirteenth Naval District (Pacific Northwest) and the Northwest Sea Frontier, the coastal waters of Oregon, Washington, and Alaska. He would be eclipsed by the operations of Bill Halsey and Raymond Spruance, but they both owed much to his steady, tactical competence throughout the pivotal year of 1942, and, so too, did Nimitz and King.

Nimitz later gave Fletcher a photo of himself autographed “11 Nov. 42, Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, A fine fighting admiral and a splendid shipmate, with much affection, C. W. Nimitz.” Their letters throughout the war and afterward were frequently addressed “Dear Chester” and “Dear Frank Jack.” Nimitz even once sent Fletcher “a fine safety razor with accompanying brushless cream,” for which Fletcher was “very grateful to be remembered by you.” King, for his part, made only passing reference in his memoirs to Fletcher being at Coral Sea, a circumstance repeated by King’s principal biographer.17

In early September, King headed west to confer once again with Nimitz in San Francisco. But this time he brought a surprise with him. Bill Halsey was rested and well and itching only to get back into the fight. Just the week before, Halsey had told a packed auditorium of midshipmen at Annapolis, “Missing the Battle of Midway, has been the greatest disappointment of my life, but I am going back to the Pacific where I intend personally to have a crack at those yellow-bellied sons of bitches and their carriers.”18

At their three-day conference, King and Nimitz spent considerable time dissecting the disastrous cruiser defeat at Savo Island, and, with Halsey’s return, it was only natural that they would start with Ghormley and review the entire command structure in the Pacific. Halsey was to have his old job back as commander of the Enterprise task force and assume Fletcher’s role as senior tactical commander whenever the dwindling carrier forces acted in concert. If King had been suspicious of Fletcher’s command abilities, he had quickly grown equally so of Ghormley’s, even though both he and Nimitz had initially agreed on Ghormley’s appointment as COMSOPAC.

Nimitz promised to check out Ghormley in his usual low-key fashion and invited Halsey to accompany him on an inspection tour of the Enterprise after they both returned to Pearl Harbor. The “Big E” was in port being repaired after the damage it had suffered during the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. Nimitz had medals to present, including the Medal of Honor to Chief Petty Officer John William Finn for his inspired machine-gun defense of PBYs at Kaneohe Bay on December 7, and an announcement to make.

Halsey’s bulldog-like face was not yet well known, but his name was already well recognized throughout the navy as a fighting admiral, both for his early raid in the Marshall Islands and his daring delivery of the Doolittle Raiders. Looking lean and fit, he received little attention as he marched aboard the carrier behind Nimitz. But then Nimitz stepped to the microphone and motioned Halsey forward. “Boys,” Nimitz told the assembled sailors, “I’ve got a surprise for you. Bill Halsey’s back!” A roar went up along the flight deck. There was no hint of defeatism among this ship’s company. They were only too willing to embrace a fighter, and Halsey’s eyes brimmed with tears at the tribute.19

But there was a strong sense of defeatism in the South Pacific, and Nimitz’s next task was to ferret it out. The day before Nimitz hailed Halsey on board Enterprise, the Wasp had been sunk by three torpedoes fired from the Japanese submarine I-19 while the carrier was escorting the Seventh Marine Regiment to Guadalcanal as reinforcements, and Hornet was now the only operational American carrier remaining in the Pacific.

On September 24, Nimitz and his staff, including the faithful Hal Lamar, who was once again serving as his flag lieutenant, left Pearl Harbor in a PB2Y Coronado and flew south. After an unexpected overnight on the island of Canton because a bearing in one of the Coronado’s engines burned out, Nimitz arrived at Ghormley’s sweltering headquarters on the aging transport Argonne in the port of Nouméa, New Caledonia. Ghormley had not even managed to convince the French, who nominally controlled the island, to provide suitable headquarters space ashore. There was indeed defeatism in the air, but it certainly didn’t come from the marines dug in on Guadalcanal. In almost two months since its invasion, Ghormley had never visited Guadalcanal.

Having flown almost four thousand miles from Pearl Harbor, Nimitz invited MacArthur to join him in Nouméa for a joint planning session. MacArthur, only a thousand miles away in Brisbane, Australia, declined. Nimitz was welcome in Brisbane, MacArthur said, but the general was simply too busy to make the trip to Nouméa. Instead, MacArthur dispatched his chief of staff, Major General Richard K. Sutherland, and Lieutenant General George Kenney, the chief of his air forces, to meet with Nimitz.

CINCPAC had plenty of questions for all concerned. Why were Japanese reinforcements flowing through MacArthur’s territory to Guadalcanal with such impunity that the beleaguered marines there called the convoys “the Tokyo Express”? And if the situation on Guadalcanal was so desperate, why weren’t army troops arriving in New Caledonia being immediately sent to bolster them? Perhaps most disconcerting, twice during the conference at Ghormley’s headquarters a SOPAC staff officer delivered high-priority radio dispatches to Ghormley, only to have him mutter, “My God, what are we going to do about this?”20

Nimitz decided to see for himself—a courageous decision given the situation there. After flying north in the Coronado to Espíritu Santo in the New Hebrides, the admiral, joined by Commander Ralph Ofstie and Lieutenant Lamar, took off for Guadalcanal in a four-engine B-17 bomber because there was no suitable seaplane landing zone on the island. The pilot was young and a little green—as were so many men in those early days of the war—and he finally admitted to being lost, in part because there were no adequate charts of the Solomons. Lamar solved the problem by producing a National Geographic map of the South Pacific from his bag, and in the pouring rain, the big bomber touched down on the matted runway of Henderson Field.

The marines’ Archie Vandegrift was on hand to greet the admiral and tell him “hell, yes,” they could hold, but since Henderson Field was the key to Guadalcanal and Guadalcanal the key to that end of the Solomons, the airfield had to be made a strongpoint at all costs. There could be no more talk—as had come from both MacArthur and Ghormley—about pulling out.

And there was one more thing. Over a quiet, private drink later that night, Vandegrift bluntly told Nimitz that there were too many navy commanders in the theater acting timid and shying away from a fight because they were afraid of losing their ships. What was needed, Vandegrift said, were commanders who weren’t going to be taken to task by desk admirals just because they lost a ship by fighting it hard—a lesson that appeared to have been lacking around Savo Island.

Nimitz nodded. He could relate. He remembered that day long ago in the Philippines when as a young ensign with a destroyer entrusted to his command, he had run it aground and might well have sunk his career save for understanding superiors who looked beyond that one incident to see his total worth.

The next morning, Nimitz handed out medals and engaged in his usual folksy banter with the marines. Then it was time to go. In the laid-back, hard-pressed South Pacific, a barefoot Army Air Corps major with a black beard and grungy coveralls stepped forward to pilot the admiral’s return B-17. Two thousand feet of the Henderson runway was covered with metal matting; the other thousand feet, extended to accommodate B-17s, was dirt turned into mud by the rain. The departing bomber would need every foot to get airborne.

Looking over plane and pilot, Nimitz asked how he intended to take off. “Admiral,” drawled the pilot, “I thought I’d start at this end, even though it’s downwind. I can get up to flying speed easy here on the metal matting. I’ll probably be up to flying speed before I reach the dirt section.”

Several in Nimitz’s group eased into the background and made toward a second B-17, but Nimitz merely said, “All right,” and climbed right into the bombardier’s area in the Plexiglas nose of the plane. Those who were going with him got aboard as well, and the pilot gunned the B-17 down the matted runway. The jungle on either side rolled by, but when the plane hit the last thousand feet of dirt, the pilot decided that he couldn’t get airborne and aborted the takeoff. The bomber lugged into the mud, skidded toward the end of the runway, and finally ground-looped to a stop at the very end, with its tail at the edge of a steep ravine.

The pilot nonetheless restarted his engines and taxied back through the quagmire to the rest of Nimitz’s party. The admiral, as usual, was nonplussed. Climbing down from his nose perch, he simply suggested they adjourn to Vandegrift’s quarters for lunch before trying again.

By the second try, the rain had let up, and the wind freshened from the matted end of the runway. This time, Lamar saw to it that Nimitz was in a more secure seat in the fuselage. The pilot in his coveralls taxied the bomber down to the dirt end of the strip, turned into the wind, and roared down the meager runway. This time, the plane climbed into the sky, and Nimitz was on his way back to Espíritu Santo. There had been a couple of dicey moments, but Nimitz’s show of concern on Guadalcanal was a huge boost to marine morale, as well as indicative of his own style of leadership. When he returned to Pearl Harbor, he realized that he had to infuse more of the same in the South Pacific.21

By then, Bill Halsey had been growing anxious waiting around Pearl Harbor while repairs to Enterprise were completed. Finally, Nimitz ordered him south on October 15 to review the situation before Enterprise arrived on station. After stopping at Canton Island as Nimitz had just done, Halsey’s PB2Y Coronado continued on to Nouméa and had barely landed and shut down its engines when a navy whaleboat came alongside, and Admiral Ghormley’s flag lieutenant passed Halsey a sealed envelope. Inside was another sealed envelope marked SECRET.

With King’s hearty concurrence, Nimitz advised Halsey, “You will take command of the South Pacific Area and South Pacific forces immediately.” Halsey read the dispatch twice and then handed it to an aide, exclaiming, “Jesus Christ and General Jackson! This is the hottest potato they ever handed me!”22

Nimitz had become convinced that Ghormley “was on the verge of a nervous breakdown” and that the “panicky and desperate tone” of his dispatches left no doubt that he needed to be replaced immediately. If the situation was as bad as Ghormley indicated, Nimitz “needed the very best man we had to hold down that critical area.”23

In more diplomatic terms, Nimitz advised Ghormley, “After carefully weighing all factors, have decided that talents and previous experience of Halsey can best be applied to the situation by having him take over duties of ComSoPac as soon as practicable after his arrival Noumea [October] 18th your date.”24 Nimitz went on to voice his appreciation for Ghormley’s “loyal and devoted efforts,” but in a private letter to Catherine, he expressed his “hours of anguished consideration.” It was a “sore mental struggle,” but “Ghormley was too immersed in detail and not sufficiently bold and aggressive at the right times.” With the decision made, he confessed to his wife, “I feel better now that it has been done.”25

The South Pacific Area would soon feel better, too. It was certainly not all Admiral Ghormley’s fault, but the navy needed a leader who understood that “you can’t make an omelet without breaking the eggs.” Bill Halsey fit the bill. Time magazine described him as looking “saltier than sodium chloride” and “known throughout the Navy as a tough, aggressive, restless man.”26

Those who knew Halsey at all or had heard of him were quick to embrace the change. “I’ll never forget it!” exclaimed one muddy and exhausted air combat intelligence officer on Guadalcanal. “One minute we were too limp with malaria to crawl out of our foxholes; the next we were running around whooping like kids.”27

But in the beginning, Halsey would not have an easy time. In fact, his first month on the SOPAC job—late October to early November 1942—was one disaster after another. Halsey prepared to build a new airfield on Ndeni, in the Santa Cruz Islands, but Japanese pressure on Guadalcanal forced him to reconsider. General Vandegrift flew south to Nouméa to confer with Halsey and hear him ask the pointed question face-to-face: “Are we going to evacuate or hold?” Never one to equivocate, Vandegrift, whom Halsey later called “my other self,” growled back, “I can hold, but I’ve got to have more active support than I’ve been getting.” Promising Vandegrift everything he had, Halsey immediately canceled the Ndeni operation and poured all of his available resources into reinforcing the marines on Guadalcanal.28

Scarcely had this decision been made when a major Japanese force of carriers, battleships, and cruisers attempted another end run around the eastern Solomons, similar to the one that Fletcher’s carriers had met and repulsed two months before. Patched-up Enterprise, back on station in the South Pacific, moved with Hornet to intercept. Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid was in command of the combined Enterprise and Hornet task forces, and Halsey exhorted him, “Strike—Repeat—Strike.”

A PBY Catalina from Espíritu Santo found the Japanese fleet just before dawn, but a mix-up in radio communications delayed the news at Kinkaid’s carriers for a full two hours, giving the Japanese a head start in attacking the Americans. Enterprise came away damaged, but Hornet took the brunt of the blows, and Kinkaid was forced to order the ship sunk. Halsey never forgave him—neither did a host of naval aviators.

The general feeling was that in directing control of both Hornet and Enterprise, Kinkaid, a battleship admiral, had allowed the combat air patrol (CAP) being flown by Enterprise for both carriers to drift away from Hornet. Halsey simply thought that Kinkaid had not been aggressive enough in launching preemptive attacks. But Halsey also came under subsequent criticism for having pushed his carriers too far north, near the limit of Allied land-based air support, instead of keeping them south of Guadalcanal and focusing on its defense. In any event, this action was part of the growing pains of multiple-carrier operations. It was the last time a non-aviator commanded a carrier task force, but equally important, it put Halsey and Kinkaid on less-than-friendly terms.29

Tactically, the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands was a Japanese victory, but improved American antiaircraft batteries and fighter pilots took such a heavy toll on Japanese carrier-based planes that all three Japanese carriers, among them the heavily damaged light carrier Zuiho, were forced to return to Japan for more planes and pilots. Japan could not match the ever-increasing supply of both warplanes and pilots beginning to flow from the United States.

The fight for Guadalcanal was far from over, but at least Japanese carriers would no longer play a role. After being on the SOPAC job two weeks, Halsey sent an eight-page, single-spaced “Dear Chester” letter to Nimitz. It was full of information and analysis, but short on complaining—exactly as Nimitz had hoped. “I have been fairly well occupied,” Halsey told Nimitz, and “as a consequence, this is one of the first opportunities I have had to write.

“As you may well imagine,” Halsey continued, “I was completely taken aback when I received your orders on my arrival here. I took over a strange job with a strange staff and I had to begin throwing punches almost immediately.” First, there was the issue of a proper headquarters ashore. “The so-called Fighting French,” as Halsey called them, were still playing “a Ring around the Rosey,” but he intended to have all headquarters elements of the various commands moved into one building ashore within the week, because “as you must have seen, while here, it is perfectly impossible, to carry on efficiently on this ship [the Argonne].”

Nor did Halsey intend to waste precious time sending ships back to Pearl Harbor for repairs. “It will be my utmost endeavor,” Halsey assured Nimitz, “to patch up what we have and go with them… This may mean operating the Enterprise with a slightly reduced complement of planes and under difficulties, but under the present circumstances, a half a loaf is better than none.”

And “Fighting Bill,” as at least one newspaper report had already labeled him, was determined to keep that half loaf intact. Maintaining battleships and carriers continuously at sea in submarine-infested waters was a mistake—a deadly mistake, Halsey might have said, remembering Wasp caught sailing the same support area. “On every occasion so far our intelligence has given us two or more days notice of impending attack. At present it is my intention to hold heavy ships out of the area and to depend on these reports for bringing them in when the necessity arises.” In pencil in the margin of Halsey’s letter, Nimitz wrote, “I agree,” and initialed the comment “CWN.”

But how was this son of a sailor getting on with the army? The army, Halsey wrote, was “the biggest and best thing… They have made available to us various mechanics, electricians and welders, and I would like to see it widely advertised that the Army is helping us here. I have never seen anything like the spirit there is in this neck of the woods.” This time, Nimitz’s initialed margin note called for a letter to King quoting the appropriate text.

Wrapping up with a paragraph that would have done an FDR fireside chat proud, Halsey assured Nimitz that while “we are in need of everything we can get,” such a reminder was “not offered in complaint or as an excuse but just to keep the pot boiling.” The men around him were “superb,” Halsey concluded, and “not in the least downhearted or upset by our difficulties, but obsessed with one idea only, to kill the yellow bastards and we shall do it.” Alongside which Nimitz scrawled in the margin, “This is the spirit desired.”30

And it would take more of that spirit, because despite having turned their carriers around after the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, the Japanese were still making a major effort to capture Guadalcanal. Halsey learned of their latest thrust on November 10 and sent Kinkaid hurrying north with Task Force 16—two battleships, one heavy cruiser, one light cruiser, and eight destroyers grouped around the partially repaired Enterprise.

But before Kinkaid could get within range, Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner ordered Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan and Rear Admiral Norman Scott to lead five cruisers and eight destroyers against the advancing Japanese in order once again to save the beachhead and Henderson Field. Callaghan and Scott paid for the effort with their lives, but by November 14–15, Kinkaid’s battleships and planes flying from both Henderson Field and Enterprise had inflicted heavy losses among the Japanese convoy and its escorts.31

Although American cruisers would take one more beating, again at the western end of Ironbottom Sound from Japanese torpedoes at the Battle of Tassafaronga at the end of November, this marked the end of Japanese attempts to capture Guadalcanal. King’s strategy of taking the offensive to protect the West Coast–Australia sea-lanes and build a stronghold from which to start the drive toward Japan had worked after a frightful cost—twelve hundred American marines lay dead on Guadalcanal, and upwards of four thousand American sailors rested beneath the surrounding seas.32 But the tide had been turned. In recognition of his “can-do” leadership and the mounting forces under his command, Bill Halsey was promoted to the four stars of full admiral, joining Leahy, King, Nimitz, Stark, and the Atlantic Fleet’s Royal Ingersoll in that rank.

The promotion and his success in the Solomons put Halsey on the cover of Time, although the magazine was quick to point out that the painting depicting Halsey with only three stars had been commissioned before his promotion. This was the American public’s first really good look at Bill Halsey, who had a “pugnacious” nose, “aggressive” eyes, and eyebrows “as impressive and busy-looking as a couple of task forces.” It is important to note that no one had as yet called him “Bull.” Instead, the article reiterated Halsey’s mantra: “Hit Hard, Hit Fast, Hit Often.”

Nimitz’s own comments in the cover article did much to cement Halsey’s image with Time’s readers. “Halsey’s conduct of his present command leaves nothing to be desired,” Time quoted Nimitz. “He is professionally competent and militarily aggressive without being reckless or foolhardy [and] he has that rare combination of intellectual capacity and military audacity and can calculate to a cat’s whisker the risk involved…” His nomination to admiral by the president, Nimitz concluded, was a reward “he richly deserves.”33

Four-star insignia were nonexistent in the supply-short South Pacific, but two rear admiral two-star insignia were quickly welded together. Halsey removed his vice admiral’s stars, handed them to an aide, and reportedly said, “Send one of these to Mrs. Scott and the other to Mrs. Callaghan. Tell them it was their husbands’ bravery that got me my new ones.”34

In a lengthy letter to Nimitz that same month, Halsey stressed “a crying need for boats of all kinds,” including “some of the laid up boats in Pearl.” Nimitz’s margin note was again to the point: “Send them,” he ordered. A tank farm was under construction on Guadalcanal, and once it was completed, Halsey expected “to be able to blast hell out of the Japs in the Shortland [western Solomons] area and later on at Rabaul.” Signing himself, “As ever, cheerfully yours, Bill H.,” Halsey reiterated that his command was “not in the least downhearted” and “as you may rightly interpret, my growls and grouches are the privileges of an old sailorman.”35

But Halsey had more requirements to wage war than just men and ships. In the same letter to Nimitz, Halsey wrote, “Please tell Raymond [Spruance] to discontinue personal shipments to me. We have made other arrangements here. In the meantime, I am deeply appreciative for what he has done.”

And just what was that? In addition to now serving as Nimitz’s chief of staff and housemate, Spruance had also had the job of keeping Halsey supplied with alcoholic refreshment in the first weeks after he was dispatched to the South Pacific. Henceforth, another Halsey buddy, Rear Admiral C. W. Crosse, in the Service Force of the Pacific Fleet, would handle that task. “A little preliminary dope so that you won’t get nervous,” Crosse told Halsey in a “Dear Bill” letter. “I have your verbal directive (threat) via Mason, namely ten cases of scotch and five cases of bourbon monthly. Can do.”

The shipments, charged to Halsey’s personal account, were to be “marked with the usual shipping indicators for Nouméa but will also have three stars stenciled on the cases to indicate the consignee as old Killer Bill.” By the time this letter reached Halsey, Crosse was one star short and someone, perhaps Halsey himself, penciled “4 stars” in the margin of the letter. Crosse went on to propose a code for future correspondence, including a promised radio message whereby a reference to “urser ten dash five” would mean ten cases of Scotch and five cases of bourbon. War or not, someone, it seemed, had time on his hands. In a postscript, Crosse noted, “Your crowd at Nouméa were sadly lacking in any recreational equipment,” and he promised to send along baseball gear to distribute “among the boys and let ’em go to it.”36

A week later, Crosse wrote Halsey the “latest dope on ‘10-5,’ advising, “Ten cases of Black & White are loaded in the S. S. JOHN BABCOCK, scheduled to leave here the 28th and ETA EPIC [Nouméa] is December 20th.” Crosse gave Halsey the name of the chief mate who had signed for the special cargo and told him, “In case you are thirsty and can hardly wait, it is stowed in a locker on the boat deck, starboard side, aft.”37

Alcohol was a cherished commodity in all commands and all theaters throughout the war and a much-sought-after form of unwinding after the stress of battle, whether in the cockpit of an F4F Wildcat or a sweltering office nervously awaiting radiograms describing the action. Ironically, one of the few top commanders who usually eschewed hard liquor—save maybe a rum punch—was Raymond Spruance, Halsey’s early supplier.

Later, when it became easier logistically to supply all commands with a liquor ration, many commanders, Halsey included, continued to get their own personal shipments. As a COMSOPAC directive pointed out some months later, these shipments to Halsey were outside the scope of the regular shipments to Nouméa because “such stores [Halsey’s personal supply] are maintained largely for the purposes and needs of official and semi-official entertaining.” Weekly consumption was estimated “to be approximately limited to one bottle per regular mess member, which is, however, exclusive of entertainment requirements.”38

And so, as 1942 drew to a close, Allied troops around the globe paused to celebrate another wartime Christmas. It had been a year in which the issue had been in doubt more times than not. But in hindsight, despite ferocious losses of men, ships, and planes, it was remarkable what the entire Allied effort had accomplished in just one year’s time, since the attack on Pearl Harbor.

In the South Pacific, Guadalcanal was secure. MacArthur’s forces had saved Port Moresby and pushed the Japanese back across the Owen Stanley Range. The British had won a decisive victory in Egypt at El Alamein and were pursuing Rommel’s Afrika Korps across North Africa toward the Allied forces landed under Operation Torch. In Russia, the expanse of that country and the determined resistance of its soldiers had worn down the German onslaught, and the Russians had entrapped a portion of the German forces at Stalingrad.

There would be many more moments of high drama and uncertainty, but on all fronts, November 1942 had been a watershed that forecast a hint of victory. It was far from the beginning of the end, but it was, as Winston Churchill opined, “perhaps, the end of the beginning.”39

Ernest King’s portrait appeared on the cover of Time the week after Halsey’s. The cover date was December 7, 1942. “I’d say they started something at Pearl Harbor that they are not going to finish,” remarked the admiral. “We are going to win this war.” Indicative of the general measure of increasing confidence, King talked more freely than usual with the press about the year’s successes as well as its losses. Perhaps most important, he repeated what he had said at the beginning of the year: “Our days of victory are in the making.”40

When Chester Nimitz was asked which moment during the war had scared him the most, he replied, “The whole first six months.”41 But now to all of his fighting men in the Pacific, he sent this Christmas greeting: “To all fighting men in the Pacific X On this holiest of days I extend my greetings with admiration of your brave deeds of the past year X The victories you have won, the sacrifices you have made, the ordeals you now endure, are an inspiration to the Christian world X As you meet the Jap along this vast battle line from the Aleutians to the Solomons, remember, liberty is in every blow you strike X Nimitz”42

There was a momentary lull in the interservice wars in Washington as well. Having begrudgingly come to respect each other, General Marshall and Admiral King exchanged cordial Christmas notes. “Dear King,” wrote Marshall, “This is a note of Christmas greetings to you, with my thanks for the manner in which you have cooperated with me to meet our extremely difficult problems of the past year. With assurance of my regard and esteem, and full confidence in the prospects for the New Year, Faithfully yours, George Marshall.”

“Dear Marshall,” King responded a day later, “I wish to thank you for your kind note of Christmas greetings and to express my hearty reciprocation of your views as to the manner and extent of our cooperation throughout the past year. With the background we have, I am confident that we will go on to even closer cooperation in the conduct of the war. With renewed assurance of my respect and esteem, I am, faithfully yours, E. J. King.”43

The momentary pause on all fronts even caused a lull in the ongoing feud with MacArthur, although King, for one, would never be taken with him. King always resented MacArthur’s sharp criticism of the early efforts of Admiral Thomas Hart’s tiny Asiatic Fleet against the Japanese onslaught—something akin to stopping a flood with a paper towel. Then, too, King was used to being his own favorite martinet. Neither he nor MacArthur was accustomed to sharing the stage with anyone.

Halsey would come to seek his own moments in the sun, but he would do so much more as “one of the guys”—the top guy to be sure—but his demeanor was far friendlier and folksier than anything King or MacArthur evidenced. King’s cameo roles as “one of the guys” during his prewar partying had long since stopped, and Douglas MacArthur was never one to have really close friends. Ironically, one of those historically closest to him—other than MacArthur’s similarly self-important wartime chief of staff, Richard Sutherland—may have been Dwight Eisenhower, because of their long association in Washington and the Philippines.

Halsey, who had yet to meet MacArthur face-to-face, couldn’t resist tweaking the general just a little for his rather plush headquarters in Brisbane. “Would not MacArthur enjoy knowing,” Halsey asked Nimitz parenthetically in one of his letters, “that we are sending people from the combat zone for rest and recuperation, in sight of his headquarters?”44