IT’S CALLED ART THERAPY!

To make prison life even worse, Richard discovered his precious comic books were forbidden as reading material because they were not considered “educational” in nature.

“They had a rule, at least in California prisons, which quit allowing comics to be shipped in sometime in the ’90s. Periodicals had to be mostly text so that they’d be ‘educational.’ The hypocrisy of it was they’d allow guys subscriptions to magazines like Maxim and FHM, yeah, they’re educational, OK. There were some old comics in there from the ’80s that guys kept and would trade.”

Eventually, he was able to get a subscription to Wizard magazine after pleading his case with prison officials, explaining that it wasn’t a comic book, but a magazine devoted to news of the comic industry.

“They held my first issue about three months deciding if they were going to let me have it or not,” Richard says. After they forked it over, Richard soon found that his stack of Wizard back issues and his creative art ability became a commodity for him.

“Once I had them a couple months, I would trade them for food or whatever to the guys that did tattoos—they’d trace the pictures and use them as patterns, or use them to make birthday cards for their kids, tracing Batman or Spider-Man,” Richard told me in an interview. “I made a little money doing that, drawing cards for guys. I don’t remember what the going rate was. One of the big currencies was Top Ramen, and guys would buy those by the caseload at the prison store. I wasn’t a fan—the salt content alone will kill you—but Joe ate one every day. I don’t know how he kept from dying from a heart attack.” Richard added that other popular trade items were Sriracha and peanut butter packets. Food was valued in prison because good food was rare. Richard says he lost 15 pounds off his lean frame while in Soledad, his least favorite memory being the prison bologna.

“True mystery meat,” he said. “We had stray cats that would come around the yard to be fed. They would not touch the bologna.”

Another currency, but one Richard didn’t truck in, was Pruno.

“Toilet wine,” Richard said with a laugh. “They wouldn’t give you much juice, because guys would turn it into Pruno. They’d ferment it three days in the toilet, they’d steal yeast from the kitchen, that’s what they call the ‘kicker,’ they’d put in a plastic bag, and they’d hide it in the ceiling tiles of the dorm. They’d let it sit up there at least three days, then drink what I’d call furniture polish. No matter how many times the guards went around and found these bags, the dorm always smelt like Pruno. Always.”

ALTHOUGH COMIC BOOKS WEREN’T allowed in, there was no rule about creating them. Richard was approved art supplies like paper and colored pencils, and filled his spare time drawing. He began work on a major project: his graphic novel-length comic book titled Prison Penned Comics. The first major story in the book is an autobiographical comic, “Phantom Patriot: The Skeleton in America’s Closet,” which details his motivations and raid on the Bohemian Grove, and his court date. The comic storyline is accurate about how the events went down but filtered with his own spin.

Richard joined the prison art program and began creating his comic using available supplies, and would spend time drawing on a clipboard in his bunk. He scoured the prison’s magazines and books for visual references and sent Lon a long list of pictures he was looking for. He made do with what he had. One panel shows a skyline of Austin, which Richard created by speed-sketching during the opening credits of PBS’ Austin City Limits. Richard was hoping this autobiography would finally get his story attention. As he started the project in 2005, he wrote to Lon that the book “could become one of the most unique comic books/graphic novels in the artform. I can’t remember seeing or hearing about any comic book based on a true story that was actually written and drawn by the vigilante himself. Also, there may be comics about prison, from time to time, but how many of them are actually created there?”

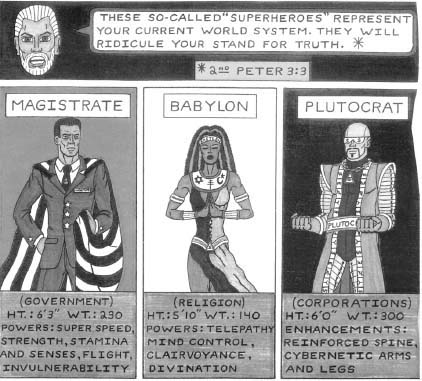

The second major story in Prison Penned Comics, “Agent of Armageddon,” is a wild, trippy fictional story starring himself, drawn during his last year in prison. Richard made a drastic (but short-lived) life change—he converted to become a Jehovah’s Witness. He decided it was time to adopt a new superhero persona to reflect this metamorphosis, and from the confines of Soledad came up with a Jehovah’s Witness superhero persona on paper: The Revelator.

“Prison is where they get a lot of guys,” Richard would later tell me, shaking his head remembering his conversion. “They had weekly meetings, and I went to one because I was curious.”

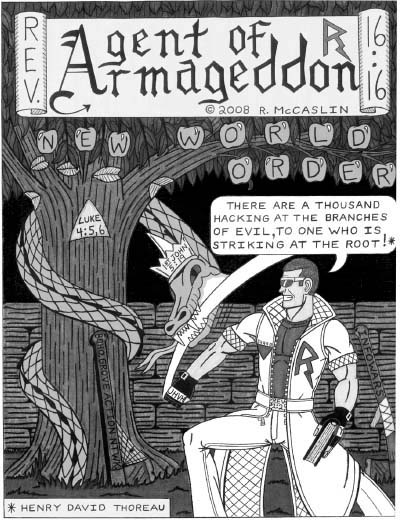

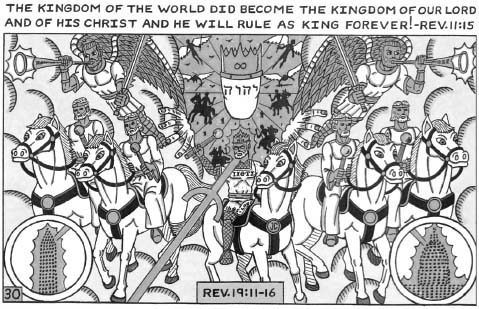

Splash page for “Agent of Armageddon,” Prison Penned Comics,2008, Richard McCaslin.

This new character wore white-rimmed sunglasses, a popped collar on a shirt with a purple triangle (the symbol Nazis marked Jehovah’s Witnesses with), and held a Bible. The Revelator looks like a cross between a street-corner preacher and a keyboardist for an ’80s New Wave band.

“This issue is what I’m sure most psychologists would call my ‘apocalyptic revenge fantasy against the Bohemian Club,’” Richard told me about the “Agent of Armageddon” comic. “Hey… I had to work through the anger and frustration of being locked up for taking on the mission of going after the real ‘Lex Luthors’ and ‘Norman Osborns’4 of this world! It’s called art therapy!”

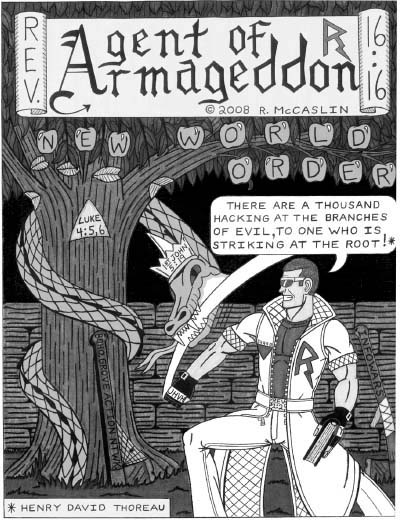

The comic starts with Richard drifting off in his bunk in Soledad. Waking up, he finds himself in the prison yard, surrounded by folk heroes Uncle Sam, Pecos Bill, John Henry, and Paul Bunyan. Also present in the roll call is the grinning, empty-eyed Phantom Patriot, who has been embraced into the league of American folk heroes. These assembled heroes offer Richard encouraging words to keep him going when he complains about the treatment his legacy has received.

“You’ve put your ax to a pretty big tree! It’s going to take a while to chop it down,” Paul Bunyan tells Richard, paraphrasing Matthew 3:10.

“What my ‘folktale fraternity’ is getting at, is this, Rich,” the Phantom Patriot says, putting a consoling hand on cartoon Richard’s shoulder. “I lost the ‘Battle of Bohemia,’ but you must press on!”

Next, Richard is visited by a glowing angel, Regnessem (read it backward) who tells Richard he has been chosen to be THE REVELATOR.

Perhaps the most “art therapy” or “revenge fantasy” scene, depending on how you look at it, is Regnessem’s and The Revelator’s wild flaming chariot ride through the Bohemian Grove. Here, the story does not end with Richard face down on the asphalt, handcuffs clipped on his wrists and four cop knees in his back. Instead, Richard and his angel find Bohos in the midst of sacrificing a baby to the Great Owl of Bohemia. The Revelator and Regnessem’s chariot obliterates the security guards with holy fire, as Revelator shouts “Woe to the wicked!” They then confront the monk-robe-clad Bohemians. Their leader’s name is Illuminus and he wears a giant eyeball on his head, a villain Richard would go on to use in several future projects as his archenemy representing the New World Order.

Richard punches him, shattering his eyeball mask, then pins his neck underneath a rope wrapped around the Great Owl. Richard saves the baby while Regnessem lifts the 40-foot statue out of the ground, flies into the air, and hurls it (struggling Illuminus and all) into the Pacific Ocean.

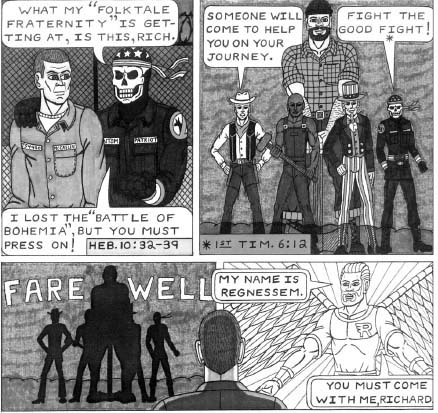

With that all wrapped up, the duo then speeds to Washington, D.C., to take on an assembly of political dynasties at the White House. Assembled in the White House’s Situation Room are George and Laura Bush and Al and Tipper Gore, two sides of the same coin. All four have the mark of the beast, 666, burnt onto their foreheads. The Revelator soon encounters a trio of false superheroes who serve as White House protectors—Magistrate, Babylon, and Plutocrat, representatives of corrupt government, false religion, and greedy corporations, respectively.

“These so-called ‘superheroes’ represent your current world system. They will ridicule your stand for truth,” Regnessem warns. Richard beats them all.

Richard helps fight in a just battle, and soon the armies of heaven join him on Earth in a battle of Armageddon, attacking the legions of hell and the corrupt United Nations army. The angel Michael leads the fight. After Satan, depicted as a multi-headed dragon, is hurled back to the depths of hell, Richard asks Michael if he will see his parents in the resurrection.

“Richard, they are in Jehovah’s memory,” Michael informs him, as his parents appear in a vision, surrounded by a holy light. Richard has a tear streaming down his face.

So there it is, neatly wrapped up in a 33-page comic: Richard finally saves a baby from sacrifice at the Bohemian Grove and destroys the Great Owl statue, Satan is defeated, the corrupt White House is overthrown, and he gets to see his parents one last time.

At the end of the comic, Richard wakes up in his bunk in Soledad. A note is next to him that reads “Keep looking, keep awake; for you do not know when the appointed time is!—Mark 13:33” Signed: “JC.”

THE PSYCHOLOGY Of CONSPIRACY

RICHARD CALLS HIS WORK “art therapy.” Court-appointed psychologists said he was “delusional.”

In their psychological profile of Richard, the Secret Service reported that his “psycho-environmental stressors” were rated as “severe” and listed his psychological abuse by his father, poor self-image, shyness, awkwardness toward women, unhappiness with his time in the Marines, lack of satisfying employment, the death of his parents, his “unsuccessful reconnaissance foray to the Bohemian Grove” and his failure to establish “a mutually satisfying personal relationship with a country singer on whom he had a crush,” as well as his legal difficulties, as impacting his mental state. The Secret Service psychologist lists in his report insight on the Phantom Patriot and the Bohemian Grove raid:

“Having grown up with an over-controlling and physically abusive father, it is perhaps not particularly surprising that Mr. McCaslin should want to come to rescue or otherwise intervene in the case of children whom he saw as enslaved or physically abused by those who are older or more powerful than they are. This seems to have made him, then, particularly vulnerable to the message of radio commentator Alex Jones about the Bohemian Grove and the supposed videotaping of child sacrifice and child slavery rituals at that location.”

The psychologist also notes that the Phantom Patriot and other superhero personas might have derived from Richard’s shyness and feelings of inadequacy with women.

“Mr. McCaslin’s report of going into the darkness of the night with his skeleton mask and in the garb of the ‘Phantom Patriot’ is reminiscent of schoolboy rescue fantasies for young damsels whom he felt too shy to approach, but with whom he was utterly fascinated,” the report notes.

The report indicates that the psychologist did not feel Richard was an excessively violent individual and noted he had been able to channel his energy into things like high school football and joining the Marines, but didn’t eliminate him as a potential threat.

“While Mr. McCaslin does not single out President Bush as being even a leader at this perceived evil band at the Bohemian Grove,” the Secret Service psychologist noted, and someone at the Secret Service reading the report highlighted the rest of the sentence, “he is quite clear he would kill anyone, including President Bush if he were to verify his suspicions that President Bush (or anyone else) is actively involved with the enslavement or murder of children.”

I WANTED TO GET more insight into how conspiracists think, and I knew someone who would be uniquely qualified to talk about Richard, as well as offer insight on similar attributes that conspiracy theorists might share.

Dr. Daniel White has a Bachelor of Science and two Ph.D.s in Psychology and Biological Anthropology. I first met him online when he was working on his Psychology Ph.D. at the University of Sydney and working on his final paper (along with five other authors) about the psychology of Real-Life Superheroes. It was published in 2016 and titled “Look Up in the Sky: Latent Content Analysis of the Real-Life Superhero Community.”

“The objective was to identify how it was possible for individuals to act in what was technically an anti-social way—for example, violating social norms by expressing extreme altruism—literally what made these individuals go above and beyond what a normal person would do,” Dr. White says on the paper. “I suspect that while many RLSH would not consider themselves anti-social, they would definitely say they are not your ordinary citizen, for pro-social goals (helping other people). In other words, how do you get pro-social anti-social behavior?”

Dr. White’s examinations of conspiracy theories have tied into his study of subcultures, and he told me he used conspiracy theories in the classroom to teach aspects of social psychology.

To help understand the id of a conspiracy theorist, I asked Dr. White what studies have shown about their personalities.

“There has been quite a bit of research into the personality of someone who believes conspiracy theories, ranging from high levels of paranoia, proneness to cognitive fallacies (such as conjunction fallacy) or even a higher tolerance for cognitive dissonance, high levels of narcissism (after all the idea that the government is spending millions spying on yourself requires a certain level of perceived self-worth), a tendency toward teleological explanations,” Dr. White explains. Teleology refers to the purpose of something’s end game: an acorn wants to become an oak tree, for example.

“There was a recent study published (in the Journal of Individual Differences) that suggests that individuals who believe in conspiracies have a lot in common with personality traits found in the schizotypy constellation; i.e. have low levels of trust, eccentric in terms of ideology, and have a higher likelihood of having unusual perceptual experiences,” Dr. White continued. “The study also said there was a strong need to feel important or unique, which might be expressed as narcissism.”

Dr. White said that he’s attended several conspiracy-themed talks and group meetings and believed everything he laid out “does sound like a very good fit.” All of what Dr. White has told me also seems to match Richard.

He mentions the study also found conspiracists “infer meaning where others do not” and that “they consider the world a much more dangerous place than it really is.”

But Dr. White also thinks there’s an essential aspect to conspiracy theorists not mentioned—a curious, truth-seeking mind.

“I’m more inclined towards a description featured in a recent Netflix documentary, Behind the Curve [about people who believe the earth is flat], in it a scientist suggests a conspiracy theorist should be considered as someone who questions (similar to a scientist—I wonder how many scientists would appear to express traits similar to those found in the schizotypy constellation) and trying to make sense of the world, who doesn’t take the ‘because that’s how it is’ approach and wants to know more, but simply doesn’t have the training or tools to explore their area of interest correctly.”

Dr. White feels the lack of skills needed to critically examine sources is the first of three reasons people believe poorly sourced, and logical fallacy-filled theories.

“Secondly, we are so used to following authority figures or perceived authority figures, that as soon as someone claims to be one, we immediately believe them. ‘Ufologist’ sounds way more impressive than ‘nutjob with an aluminum foil hat’ after all,” Dr. White says. “Those ‘selling’ conspiracy theories are better at selling themselves as experts than their mainstream alternatives, as well as what their ‘research’ finds. Science is very self-doubting in its presentation; usually, a finding is put forward as something along the lines of ‘based on our findings we can predict that the most likely explanation is…. however here are the limitations of our study.’ Compare that to ‘the government is tracking you through your mobile phone, this is a fact, and I have absolute proof of it.’”

The third and last factor Dr. White suggests is that a lot of conspiracy fits on our outlook on the world.

“(Conspiracy) often fits with preconceived notions of the world—no matter who we are or what our beliefs are—we always find first and foremost evidence to support our preconceived notions—and conversely we have a huge tendency to disregard information that disagrees with what we believe.”

Dr. White’s last statement made me realize how many people hold some conspiracy beliefs. It might not be extreme, like 9/11 false flags or fake moon landings, but everyday workplace theories of co-workers secretly conspiring against one another and keeping secrets.

HOW MANY PEOPLE OUT there are true conspiracy believers? Polls tend to vary, but many of them point to a significant part of the population who believes in at least one conspiracy. Chapman University’s 2016 3rd Annual Survey of American Fears found that when participants were asked if the government was concealing what it knew, 54.3 percent said “agree” or “strongly agree” when that statement was applied to the 9/11 attacks, 49.6 percent answered similarly to the JFK assassination, 42.6 believing there was an alien encounters cover-up, and 30.2 percent believing there was a conspiracy about Obama’s birth certificate. Interestingly, one-third of the people polled also thought there was a cover-up of the “North Dakota Crash.” If you’re not familiar with that theory, it’s because the pollsters made it up to see how people would respond to a nonexistent conspiracy.

A 2018 Monmouth University poll showed that 27 percent of people said a Deep State shadow government secretly running things “definitely existed,” with a 47 percent saying it “probably exists,” though they struggled to define what the Deep State was.

These numbers in the polls seem to indicate the theories have become more popular, but an approaching conspiracy Dark Age is something that’s been heralded for decades. As Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in a 2019 New Yorker article (“What’s New About Conspiracy Theories?”) the theme repeats itself often:

“‘It’s official: America is becoming a conspiratocracy,’ the Daily News announced in 2011. ‘Are we living in the Golden Age of conspiracy?’ the Boston Globe wondered in 2004. ‘It’s the dawn of a new age of conspiracy theory,’ the Washington Post declared in 1994.

“I have to wonder if it has become more popular or if it has always been there. After all distrust of the government is not a new thing and choosing alternative medicine over mainstream has always been around,” Dr. White says. “Certainly, it seems ‘louder’ now, but perhaps that is just a consequence of the more connected world we live in. I would agree that it does seem to be becoming a more popular way of thinking. There could be many factors—life is faster, perceived as more chaotic than ever before, there seem to be so many factors affecting every person—perhaps with so much information, it is easier to infer meaning when there is none. Maybe the reason is that modern society provides too much information and not enough tools to understand it.”

THE FUSION MINDSET

IN THE CASE OF extreme conspiracists like Richard, there is something stronger at work than run-of-the-mill cognitive dissonance. A 2019 article for The Atlantic by James Hamblin talks about something called “identity fusion.” This term describes when people strive to “create a world in which their ideas of themselves make sense.” Creating this world gives us “a sense of order, even if it means doing things the rest of the world would see as counterproductive,” Hamblin writes.

Counterproductive things a person might do to stay in this identity include self-sabotaging relationships and acting against their self-interests to maintain their beliefs about themselves.

“Fundamentally, fusion is an opportunity to realign the sense of self. It creates new systems by which people can value themselves,” Hamblin reports. “A life that consists of living up to negative ideas about yourself does not end well. Nor does a life marked by failing to live up to a positive self-vision. But adopting the values of someone who is doing well is an escape.”

This is where a charismatic leader comes in, someone to fuse identities with. It could be a cult leader like Jim Jones, but it could also be a self-described vocal “truth seeker” like Alex Jones or a personality like Donald Trump. These people loudly enter a person’s life, grab their attention like glue, and transform them. This new identity taken on as one’s own becomes unshakable. A person who puts on a MAGA hat and becomes an InfoWars devotee is rarely going back. Identity fusion is a rejection of anything that conflicts with this new reality.

“As opposed to cognitive dissonance—the psychological unease that drives people to alter their interpretation of the world to create a sense of consistency—self-verification says that we try to bring reality into harmony with our long-standing beliefs about ourselves,” Hamblin writes. “Once you step inside the fusion mindset, there is no contradiction.”

IN 2005, RICHARD RECEIVED what might have been his first good news in a long time.

“Judge Daum had illegally over-sentenced me,” Richard wrote. His new release date was in 2008, for a total of six years in prison, followed by three years parole. He wrote to Lon a couple of months before his release, telling him he was looking forward to getting a hotel room when he got out, so he could have his own space.

“I’m just sick and tired of smelling armpits, a-holes and cigarette smoke!” Richard wrote.

Richard was released from Soledad on May 19, 2008. He was a free man. He spent “about half the day” waiting for paperwork to be filled out, then had a prison guard escort him to a bus station in “a little town, I can’t remember the name.” The guard waited until Richard got on a bus out of there.

“It’s funny now when you look back at it, but not when you’re living it. I guess you can get used to anything, and you get in a routine. I sure wouldn’t want to go back,” Richard told me. “If something happened and the cops caught me, they’d have to shoot me, because I would not go back there. I was making a statement the first time I went to prison. Anything past that is a waste of time, a waste of life. I remember the first time I drove past San Quentin and Soledad, and it felt weird, you look over and say, ‘I spent several years of my life in there, and now I can drive right on by it.’”

4 If you aren’t a comic book fan, Lex Luthor is the archnemesis of Superman; Norman Osborn is the wealthy scientist who becomes the Green Goblin villain in the Spider-Man stories.