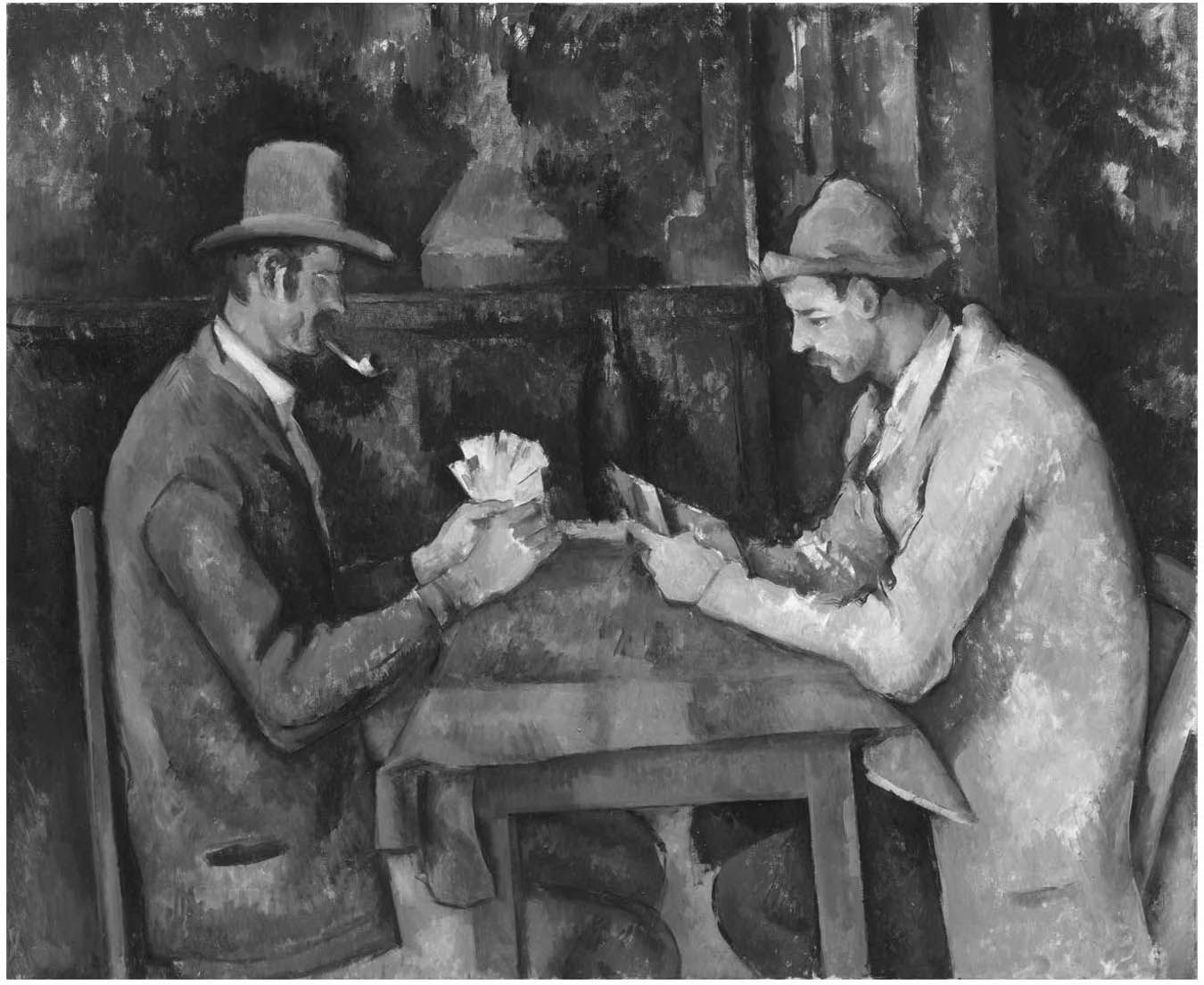

Unfortunately for the topic of this book, on first sight, the Surrealists’ ambiguous enthusiasm for Symbolist art, thought and writing, and their lesser-known favourable disposal towards the art of those who came after Impressionism, such as Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, Vincent van Gogh and even the later Pierre-Auguste Renoir – all of whom receive an auspicious outing within Surrealism at some point – were not extended to the painting of Paul Cézanne. Why this was the case among Surrealist artists and writers is probably obvious to anyone who knows anything about the movement but should be gone into briefly here for those who do not and for the historical record. More interesting is the single exception to the rule: the passage written by André Breton in 1936 for his book Mad Love (1937), which has hardly ever been commented upon. Breton attempted there to corral a number of Cézanne’s paintings including one of the two-figure compositions titled The Card Players (1892–3) into a Surrealist paradigm. In this first chapter, I will be examining the latencies of Breton’s interpretation in the context of Surrealism’s theoretical orientation in the mid-1930s. But I will also be setting a pattern for my other chapters by looking beyond the boundaries of the movement at the larger reception of the artist by modernist critics and others in the twentieth century to ask the unexpected question: why Cézanne for Surrealism in 1936?

Surrealism’s disdain for the Master of Aix is demonstrated loudly and clearly at two points in its long trajectory. In an essay on his friend André Derain, published in the periodical Littérature (thirty-three issues, 1919–24) early in 1921 while Dada was still functioning in Paris, Breton channelled the artist’s own words to refer cautiously and sceptically (and optimistically, as it turned out) to Cézanne’s glowing reputation as perhaps about to dim, and to his art as ‘flattering like make up [la poudre de riz]’.1 ‘This man,’ he continued, ‘who has captured the world’s attention, was perhaps completely mistaken.’2 A pretty, quasi-Impressionist superficiality can be read into that remark: Breton was still in the process of detaching himself from art-loving mentors like Paul Valéry on whose walls he later recalled seeing ‘[b]eautiful Impressionist canvases’,3 while articulating at the time a Dada stance that conceived of ‘art only as a means of despairing’.4 In this passage, however, it sounds like Cézanne’s mistake was to rely too heavily on the senses, whereas ‘Derain is not a subjectivist.’5

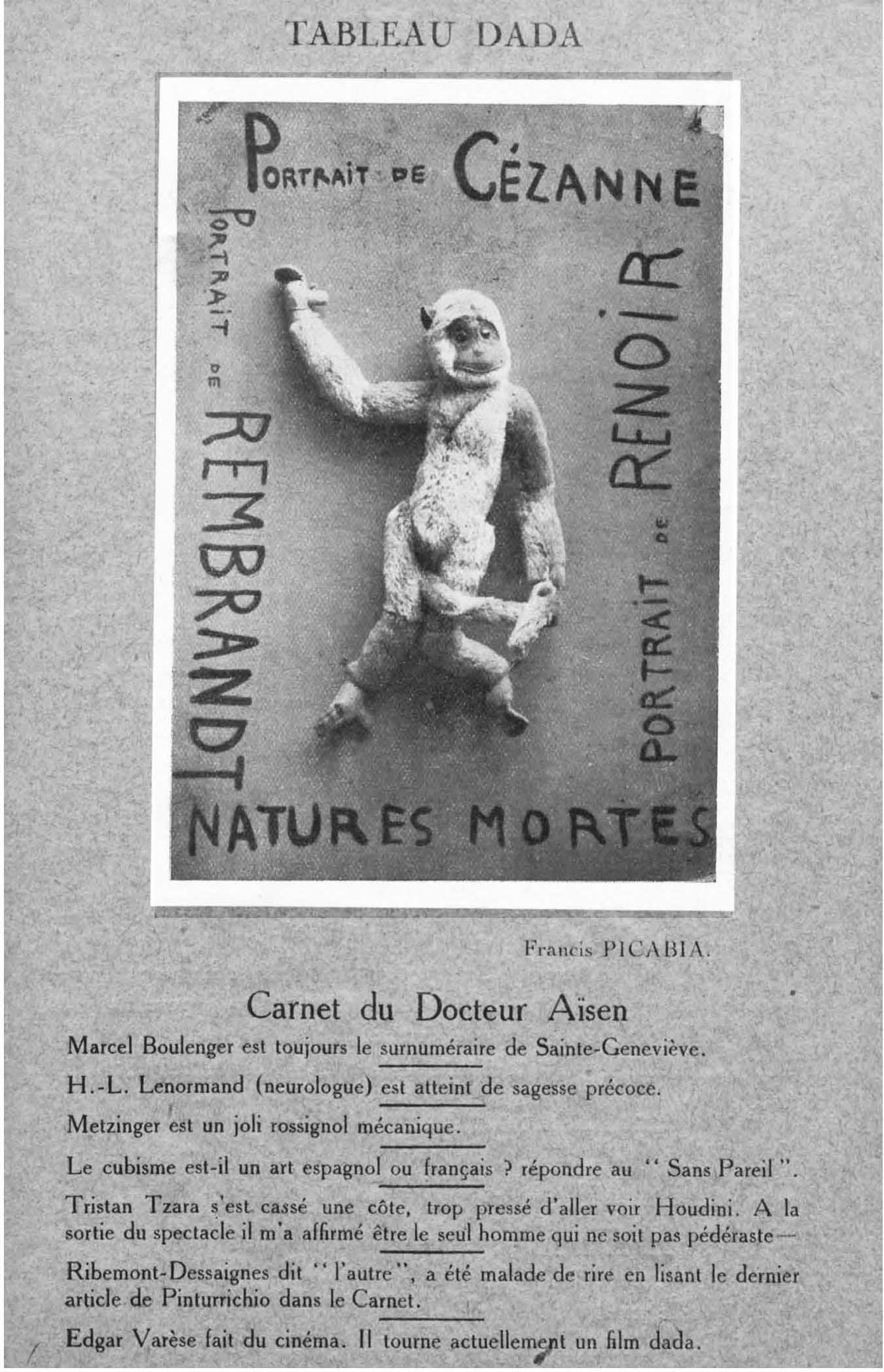

Breton’s negative take on Cézanne had been hardened by his on/off acquaintance in the first half of the 1920s with Francis Picabia. They were close at the time of the fabrication of Picabia’s ultra-Dada statement: the iconoclastic, numerously insulting Still Lives (figure 1.1, 1920), which Breton apparently had a surprising role in deradicalizing.6 This long-gone Dada masterpiece was first shown on stage at the Dada Manifestation of 27 March at the Maison de l’Oeuvre and was probably sparked quite specifically by Renoir’s recent death. That event is celebrated in the title and by the cheerfully wanking, merrily waving stuffed monkey attached to cardboard, along with the presumed or hoped for death of genre, particularly those of the portrait, still life, nude and landscape.7 A precedent can be found in February 1919 on the cover of the eighth number of Picabia’s review 391, which carried the legend ‘I have a horror of the painting/of Cézanne/it bores me’ (‘j’ai horreur de la peinture/de Cézanne/elle m’embête’) in tiny script over the editor’s name.8 A few years later in 1922, Breton puckishly reported Picabia’s remark, conveyed by the artist supposedly from its original source in ‘a member of the high Persian nobility’ (one Surkhai Sardar), who thought Cézanne’s apples, pears and lemons gave evidence of the ‘mind of a greengrocer’.9

Also that year, in his state-of-play lecture introducing Picabia’s exhibition at the Dalmau Gallery in Barcelona in November, Breton opened a parenthesis to announce that the most important contemporary art – of Pablo Picasso, Picabia, Marcel Duchamp, Giorgio de Chirico, Man Ray and Max Ernst, which then stood between Cézanne and a not-quite evolved Surrealism – owed nothing to Cézanne himself (not even Picasso’s work, apparently):

Figure 1.1 Francis Picabia, Still Lives (1920). Mixed media, dimensions unknown. Reproduced in Cannibale, no. 1, 25 April 1920. Current whereabouts unknown. Image © University of Iowa Libraries. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018.

(it would be absurd to speak in their regard of Cézanne, about whom I personally could not care less and whose human attitudes [l’attitude humaine] and artistic ambitions, despite what his flatterers say, I have always considered imbecilic – almost as imbecilic as the current need to praise him to the skies).…10

Breton went on to supplant the ubiquitous Cézanne, the painter’s painter and arty technical master – beloved of or at least respected by the likes of Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Renoir and Camille Pissarro (and most perceptively analysed early on, too, by the painters Émile Bernard and Maurice Denis) – with the artist’s obscure nineteenth-century contemporary the Comte de Lautréamont. Picasso and the others had not even read Lautréamont’s Chants de Maldoror (1869) at this stage. Yet to that long-dead, little-known writer fell ‘perhaps the greatest responsibility for the current state of affairs in poetry’, according to Breton, who then made a case for a visual art not of the senses but of the imagination as extrapolated from his avid reading of Lautréamont.11 This imagination was one of ‘hallucinations and sensory disturbances in the shadows’,12 and the Truth it sought to uncover went beyond the usual dualistic morality, displayed in an end product that ‘no longer has a right or wrong side: good so nicely brings out evil’.13

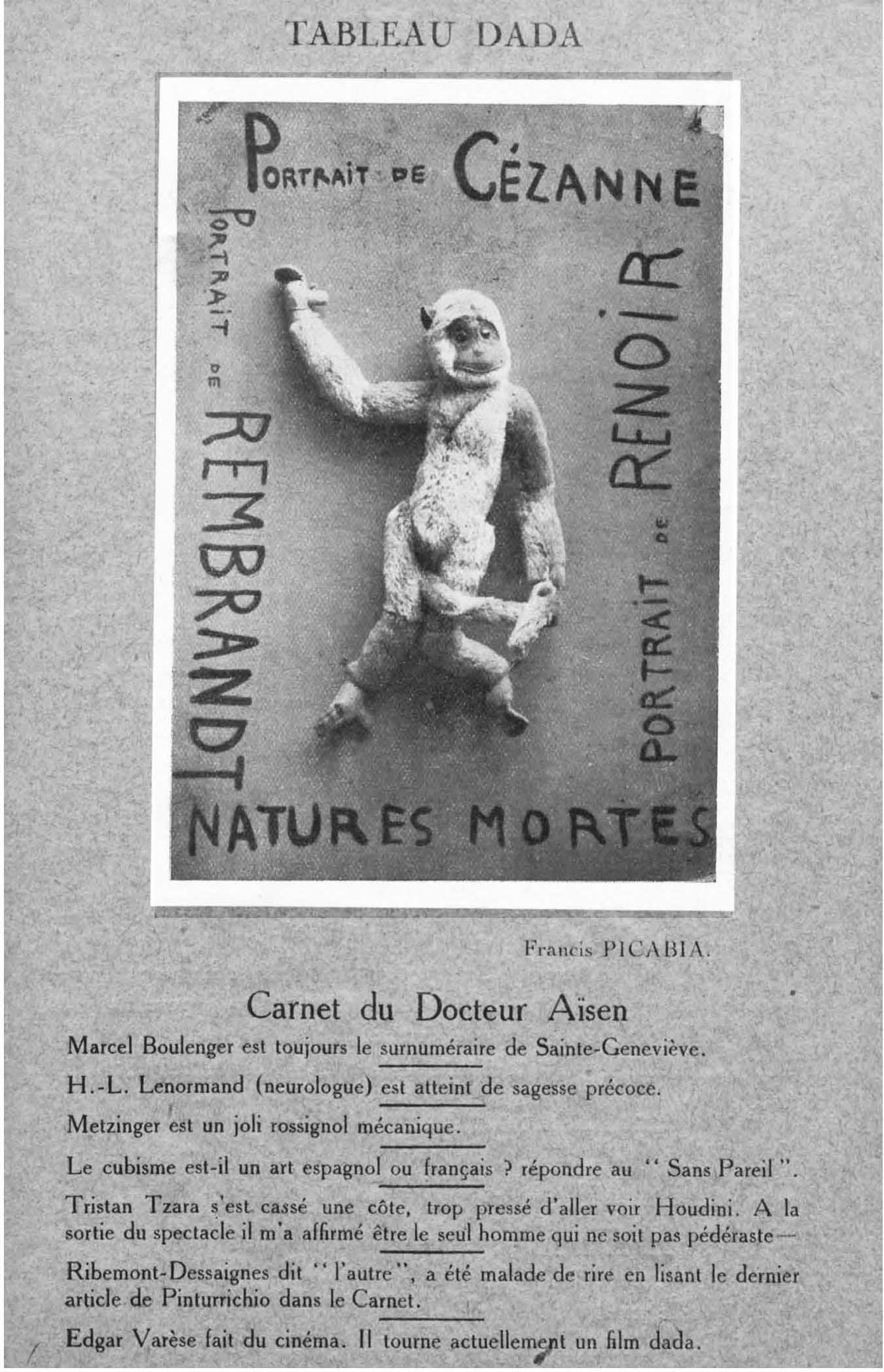

As opposed to the art of rational construction (figure 1.2), against which the success of Cézanne’s work was endlessly gauged by its admirers and which was and is the indissociable outcome of an artistic practice borne by conscious awareness (whatever the debate that has raged since Bernard through and beyond Joachim Gasquet over whether the primary sensible substance of his practice was one of ‘spontaneous finding or of controlled making’), Breton was at this stage advocating an art in which the emphasis was laid upon content at the expense of technique.14 Automatism had still not been introduced into the visual arts in 1922, and at that time the work of de Chirico was thought of by the soon-to-be Surrealists as the main source of illumination for painting, as could be seen in Ernst’s contemporary work. What Breton sought to inject into the visual arts as characteristic of the ‘modern evolution’ were those elements of modern writing that, like Lautréamont’s and those of Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud, would ‘convey that debauchery was still the rule most applicable to the mind’.15 Cézanne’s mature canvases, of course, did nothing of the kind, but there is a first hint here of the latent material that Breton would later view in Surrealist painting and subsequently dig hard to discover layered through Cézanne’s oeuvre.16

Figure 1.2 Paul Cézanne, Houses at L’Estaque (1880). Oil on canvas, 80.2 × 100.6 cm. Art Institute of Chicago. © The Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY/Scala, Florence.

Preceding the foundational Manifesto of Surrealism of 1924, Breton’s early criticism was not honed by a fully elaborated Surrealist theory, and even after Surrealism took wing from that moment, ‘[t]he continued scandals of Cézannism, of neo-academicism, or of machinism,’ as Breton put it in ‘Surrealism and Painting’ in 1926, were assumed rather than fully argued in this initial phase.17 However, the limitation such art writing already placed on the outwardly familiar pictorial language of Cézanne’s landscapes, still-lives and nudes made a sufficiently significant prejudicial contribution to the collective idea of that artist in Surrealism that he could subsequently be dismissed by those in Surrealist circles with little more than an eye-rolling groan, which would, moreover, be immediately understood by all.

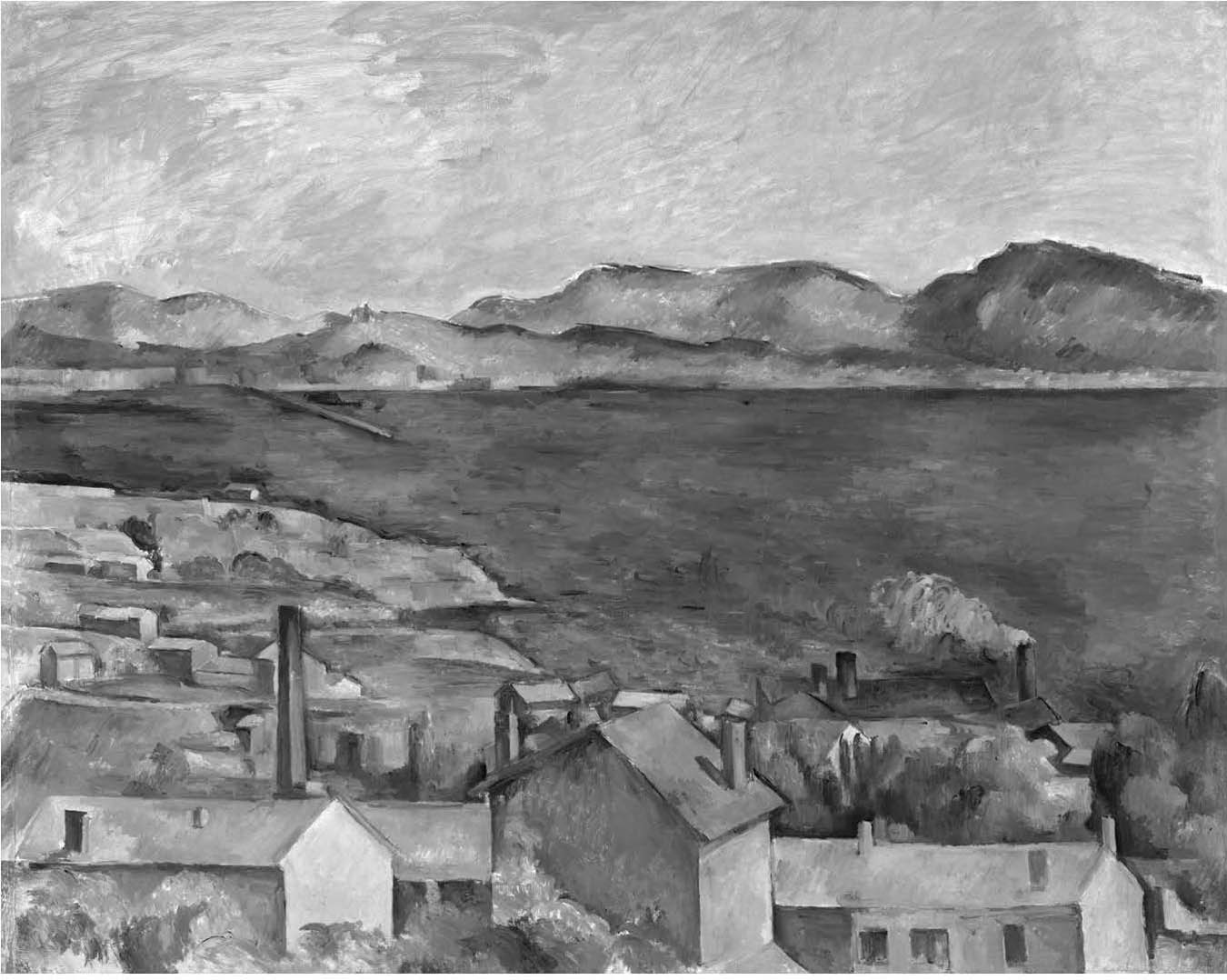

That attitude can be visited over thirty years later in the ‘precursor’ game ‘Ouvrez-vous?’ where Cézanne received such a reception on the threshold of Surrealism. Introduced in 1953 in the first number of their journal Médium: Communication surréaliste (four issues, 1953–5), ‘Ouvrez-vous?’ asks participants if and why they would open the door when visited in a dream by various long-dead ‘illustrious individuals’ (figure 1.3).18 Cézanne was poised as a potential guest among a party of thirty-four, leaning towards writers, artists and revolutionaries more or less established in the pre-Surrealist canon such as Baudelaire, Sigmund Freud, Gauguin, Goethe, Lenin, Friedrich Nietzsche, Edgar Allan Poe, Maximilien Robespierre, Seurat and van Gogh. The odds already looked stacked against him and not surprisingly the eminent artist was left standing on the doorstep more often than any other figure (receiving fifteen ‘Nons’ and only two reluctant ‘Ouis’, even fewer than Honoré de Balzac, bottom with Paul Verlaine).19 As corollaries in a game demanding speed and brevity (and, because of that, pith), the Surrealists’ reasons for cold-shouldering Cézanne are often casually and amusingly reprehensible (Jean Schuster: ‘No, because I hate apples’; Anne Seghers: ‘No, because I like apples’), demonstrating an ingrained predisposition fortified over the previous thirty years as much as anything else.20

This longstanding bias was only confirmed in the pages of the major survey L’Art magique on which Breton was beginning preparation at the time, though it would only be completed in 1957. While that book fully heralded the arrival of Gauguin into the pantheon of pre-Surrealists, as I will show, Cézanne is mentioned only in passing alongside a restatement of the dismissive 1922 ‘greengrocer’ phrase.21 In this way, Surrealism’s attitude in this later stage is doubled back onto that held in its earliest days, leaving no room for the Master of Aix in the fold.

As perhaps shown in Breton’s dismissal of the artist in the 1920s, which is robust yet lightly shaded with a youthful hesitation, Cézanne had long since reached a pre-eminent position among painters and writers on art by the time Surrealism started to bud in the period after the First World War. This was for reasons that would in no way correspond with the movement’s own idea of what painting should aspire towards. The young Surrealists’ impatience would have been compounded by the fact that Cézanne’s reputation seemed set in stone to their generation. Breton himself was born a few weeks after Cézanne achieved major recognition with his first solo exhibition at Ambroise Vollard’s in 1895 at the age of fifty-six. Surrealism’s future leader would have suffered into early adulthood the prodigious reverberations of Bernard’s 1904 article on Cézanne’s artistic methods and technical procedures, especially celebrated after it was revised and extended in 1907 for the Mercure de France (where Breton’s mentor in poetry and, to an extent, art criticism Guillaume Apollinaire also published).22 It appeared in the month following the publication of Denis’s equally laudatory piece in L’Occident.23 Breton would have known of the artist’s further rise to unquestioned greatness with the two Cézanne retrospectives at the Salon d’Automne in those years. By the time Breton began to look at art with a critical eye in 1913, Cézanne must have seemed as colossal and enduring as Mont Sainte Victoire itself, with the publication of the memoirs of Bernard and Vollard on either side of that year doing their best to bring the deceased artist back to life.24

Figure 1.3 ‘Ouvrez-vous’ in Médium: Communication surréaliste, November 1953, 1. Author’s collection.

Cézanne had by then taken posthumous paternal ownership of the keys of painting to the generation of Picasso, Georges Braque and Henri Matisse that preceded Surrealism. Yet his attitude towards his craft as ‘painting for its own sake’ (as Bernard had understood it in his earliest reflections on the artist) would never find any advocates among the Surrealists.25 As Breton had set it out in his 1920 essay on Lautréamont’s Maldoror, they believed painting could no more be reduced to a frisson that ended at the senses than poetry, but ‘must lead somewhere’, preferably all the way down to the unconscious:

It would … be a mistake to consider art an end in itself. The doctrine of ‘art for art’s sake’ is as reasonable as a doctrine of ‘life for art’s sake’ is, to my mind, insane. We now know that poetry must lead somewhere. On this certainty rests, for example, our passionate interest in Rimbaud.26

In spite of its temporary, emphatic, more commercial and populist turn towards the visual arts in the 1930s and 1940s – with its big international art exhibitions, Breton’s Galerie Gradiva and the high quality periodical Minotaure – Surrealism held to this idea of art’s purpose as a means of sounding the self and its others in the 1950s at the time that Roger Fry’s and Clive Bell’s straitlaced 1920s formalist interpretations of Cézanne as reducer and designer were extending into Clement Greenberg’s 1950s reading of the artist. As is well known, Cézanne was combatively confirmed by Greenberg at the beginning of that decade as the artist of ‘sensation’, ‘surface pattern’ and ‘two-dimensional solidity’, ‘[c]ommitted … to the motif in nature in all its givenness’ and said to have ‘cover[ed] his canvases with a mosaic of brushstrokes whose net effect was to call attention to the physical picture plane’ from the late 1870s, as though he were already laying the paving stones of the flat and even path leading to abstract expressionism (figure 1.4).27

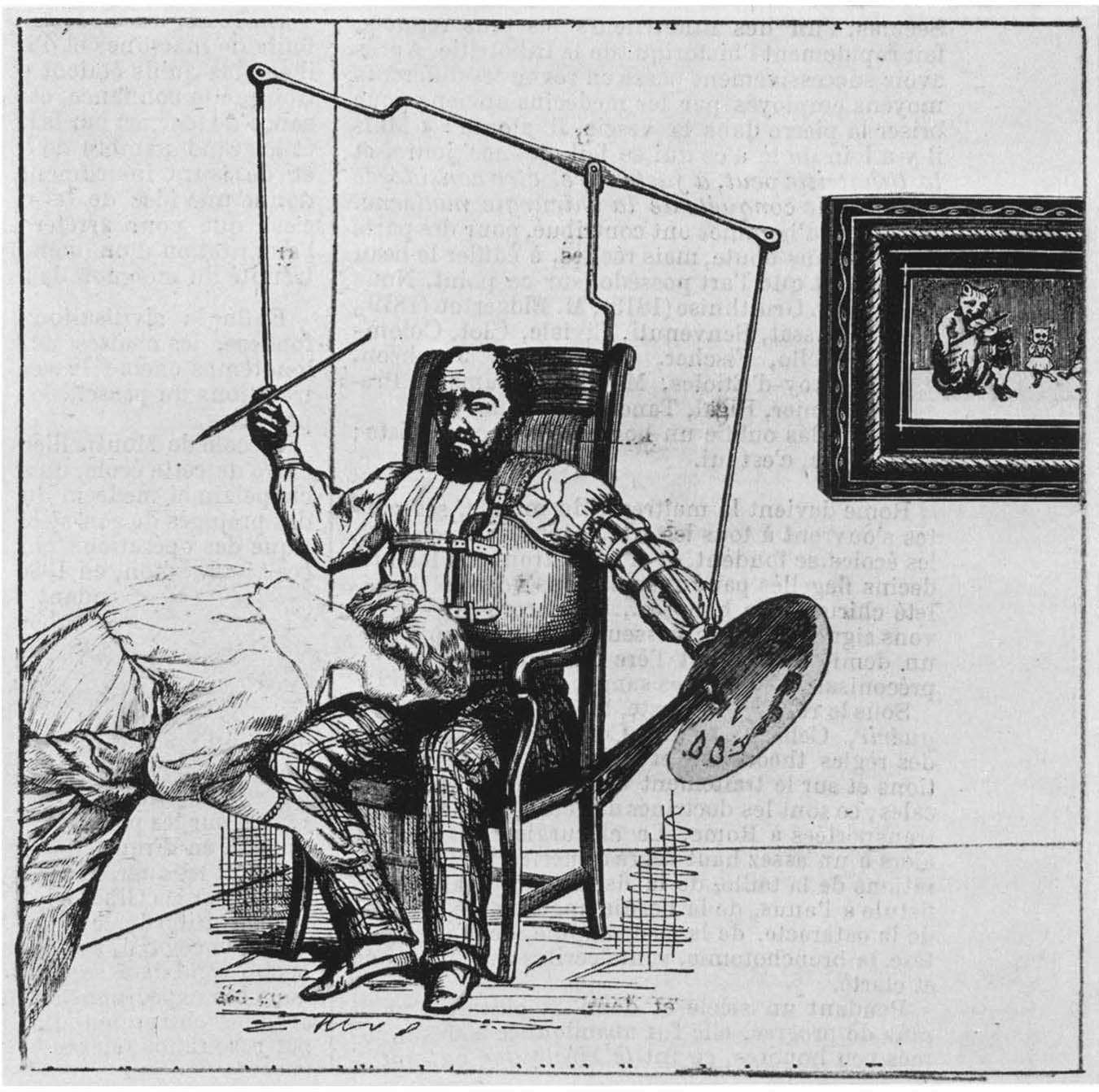

It has been stated that the Surrealists scorned Cézanne as a wealthy, Catholic, conservative bourgeois, which could be true.28 Furthermore, it might be argued that Cézanne’s frequently touted ‘classicism’ would also have turned them off and even turned them against him. Such seems to have been the case for Ernst whose cartoon depiction of the solemn, trussed up artist painting with the aid of an absurd contraption while being nearly fellated by Rosa Bonheur in the eighth chapter of his collage novel The Hundred Headless Woman (1929) is akin to Picabia’s self-consciously adolescent jibe earlier in the decade (figure 1.5).29 Yet they had their pick of many versions of the artist towards which they would have been more conducive. There was the ‘romantic’ early Cézanne, almost as enigmatic as Lautréamont; the Symbolist Cézanne of the ‘sickly retinas’ admired briefly and presciently by the exemplary pre-Surrealist Joris-Karl Huysmans, whose word they revered on Gustave Moreau;30 the asocial outsider subject to ‘mystic revelation’, as Richard Shiff put it, listing Bernard, Félix Fénéon, Gauguin and André Mellerio as followers of that creed;31 the rustic regionalist or Baudelairean ‘primitive’ described by Julius Meier-Graefe as drawing with ‘the hands of a child’;32 the Cézanne who imitated Giotto in the fabrics of his card players, as advised by Apollinaire;33 or the Cézanne in possession of ‘the ardent and naïve soul of the artists of the Middle Ages’, proposed by Georges Rivière at the very time Breton was holding forth on the artist’s ‘overestimation’ and not long before the stereotypes of medievalism began to exert their sway on the Surrealists.34

Figure 1.4 Paul Cézanne, House on the Hill (1904–6). Oil on canvas, 65.7 × 81 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., White House Collection. Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Figure 1.5 Max Ernst, ‘Cézanne et Rosa Bonheur’, collage from The Hundred Headless Woman (1929). Private collection. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018.

However, it was, firstly, the emphasis laid by the artist on his motif out in nature and, secondly, that further stress placed by his admirers and critics on what Greenberg in his other essay on the artist called Cézanne’s ‘need to enhance the unity and decorative force of the surface design [so] that he let himself sacrifice the realism of the illusion to it’, or, in other words, the denial of content, that caused them to reject his art in these two periods.35 The first was interpreted by Maurice Merleau-Ponty as a debt to the Impressionists and especially to Pissarro, thanks to whom Cézanne abandoned the ‘painted fantasies’ of his work up to about 1870 and later ‘conceived painting not as the incarnation of imagined scenes, the projection of dreams outward, but as the exact study of appearances: less a work of the studio than a working from nature’, a characterization of his later work that could now be challenged in the wake of T. J. Clark’s reading of the late Bathers paintings as ‘reach[ing] back to images and directions that had been abandoned long ago, in the 1870s and even the 1860s, as if only now the means were available to complete the dream-work then begun’.36 As for the second, content was crucial to Surrealism while it was denied in Cézanne’s painting by generations of commentary on the artist from Denis onwards. Even when it was passingly noted, as in Greenberg’s ‘sacrifice’ of ‘realism’, the results were never seen to open out into anything like the surreal world that I will show Seurat led towards in my third and fourth chapters. Since the 1980s it has been routine to comment upon content in Cézanne, in the surreal-sounding ‘mysterious, meditative mood’, for instance, the ‘inwardness and mystery’ of a ‘ceremony or ritual’ presiding over the series of card player paintings.37 Yet it was only as Greenberg lauded Cézanne and as modernist criticism and historiography reached its position of dominance in the early 1950s, while the Surrealists closed the door on him one more time, that the first murmurings could be heard of what would be, in the next decade, the full-blown psychoanalytic art writing of Meyer Schapiro, perceiving in Cézanne’s art ‘the burden of repressed emotion in this shy and anguished, powerful spirit’.38

In 1936, at the midway point of this thirty-year gap between Breton’s youthful vilification of Cézanne and the confirmation it received from the participants of ‘Ouvrez-vous?’ in 1953, a flurry of Cézanne-based activity took place within Surrealism. This can be explained partly by the movement’s greater closeness to the world of art museums and exhibitions in that decade, which I touched on above, and partly because this thirtieth anniversary of his death coincided with an important period of research and curatorship on Cézanne. In that year, the Cézanne industry moved up a notch with the publication of Lionello Venturi’s catalogue raisonné, Cézanne: son art – son oeuvre, the most thorough study to date of the artist’s paintings and the first sustained attempt to rationalize the development of his art using the language of art history.39 To accompany this, Venturi contributed an article in October on Cézanne’s last years to Minotaure, the review more or less requisitioned by the Surrealists.40 Since Vollard’s ‘Souvenirs sur Cézanne’ had appeared in Minotaure in the previous year, we can assume that these essays were accepted by the review over the complaints of most of the Surrealists on the editorial board, or that their attitude towards the artist was undergoing a temporary thaw.41 This was also the year of the first of John Rewald’s many contributions to the scholarship on Cézanne, which would have a transformative effect on the understanding of the artist. Rewald himself wrote around that time that Venturi’s book would inaugurate ‘a new era of Cézannean research’ and would be ‘at the foundation of all publications on Cézanne’.42 So the middle 1930s must be regarded as a watershed moment for scholarship on Cézanne, which helps account for the cluster of responses to the artist around Surrealism.

In 1935, the recently disaffected Surrealist Roger Caillois had attempted to delineate two recent traditions in painting, one of which ran from Cézanne to Picasso, which he thought was a ‘transformative effort on a given object’, while the other went from Moreau to Salvador Dalí, viewed by Caillois as ‘realist painting of an imagined subject’.43 In saying this, Caillois ignored the Surrealist lineage long since specified for Picasso by Breton while acknowledging the by-then well-established importance given the imagination by Surrealism, its claim to a tradition and the main exponent of Surrealist ‘realism’, Dalí. In the following year, Herbert Read offered an alternative, making a half-hearted attempt to draw Cézanne into a broad Surrealist paradigm by acknowledging ‘the imaginative range of his genius’ while complaining that ‘such an art is deceptive if it does not extend our sensibility on more than a sensational level. Cézanne himself seemed to realize this,’ he continued, ‘and was not satisfied with his apples’.44

If Read went easy on Cézanne, merely patronizing him on the basis that he got the wrong balance between the senses and the imagination, other Surrealists saw no saving grace in his work. Dalí had written of the ‘great inimitable masterworks’ of Impressionism and ‘the marvellous Renoir, Monet, Pissarro, Seurat, Cézanne, etc.’ in the monthly magazine La Nova Revista in 1927 before he left Spain to join the Paris Surrealists.45 However, his involvement with the group turned his head, somewhat, about the modernist canon. Indeed, Dalí had pitched in on Cézanne before Read, suggesting in a 1933 letter to Breton the idea of a catalogue preface to his forthcoming exhibition that began with a question in the spirit of Picabia: ‘[d]o you remember a very filthy painter who called himself Cézanne?’46

As part of an increasingly active programme to extend Surrealism historically and geographically beyond the boundaries of the Paris group, Dalí returned to the theme in 1936. In the course of an article on the women of Pre-Raphaelite art, carried by the previous number of Minotaure to the one in which Venturi’s appeared, Dalí ridiculed Cézanne’s contemplative ‘Platonic’ apple.47 Arguing for the superiority of the harder-edged ‘realist’ art of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his friends over the so-called ‘distortion’ of Cézanne’s art, lauded by Bell the previous decade, the crab-like, analogical movement of Dalí’s essay travels back and forth between the two artists. It gathers in a polemic that transforms Cézanne from a greengrocer into a builder:

If we succinctly consider Pre-Raphaelitism from the viewpoint of ‘general morphology,’ taking into account Édouard Monod-Herzen’s amazing study, we will see that its aspirations are diametrically opposed to those of Cézanne.… From the morphological viewpoint, Cézanne appears to us as a kind of Platonic bricklayer who is satisfied with a programme consisting of the straight line, circle, and regular forms in general, and who disregards the geodesic curve, which, as we know, constitutes in some respects the shortest distance from one point to another. Cézanne’s apple tends to have the same fundamental structure as that of the skeleton of siliceous sponges, which on the whole is none other than the rectilinear and orthogonal scaffolding of our bricklayers, in which one discovers with amazement numerous spicules that materially realize the ‘trirectangular dihedron’ that is so familiar to geometricians. I am saying that Cézanne’s apple tends to the orthogonal structure, because in reality, in the case of the apple, this structure is dented, deformed and denatured by the kind of ‘impatience’ that led Cézanne to so many unhappy results.48

Dalí’s paranoiac-critical mode of interpretation demanded the annexation of spontaneous irrational associations experienced by the viewer into the reading of the phenomena under observation – here, Cézanne’s apples. By means of this method, his sideways recollection of an image that accompanied the discussion by the decorator and librarian Édouard Monod-Herzen in his Principes de Morphologie Générale (1927) of the internal structure of sponges and amoeboid protozoa (figures 1.6 and 1.7), where they are compared by that author to ‘the scaffolding of our builders, rectilinear and orthogonal’, was allowed space in Dalí’s appraisal of Cézanne.49 The same is true of Monod-Herzen’s text, which he decanted more or less completely into his own.

Figure 1.6 Cover of Édouard Monod-Herzen, Principes de Morphologie Générale, vol. 1 (1927). Author’s collection.

Figure 1.7 Page from Édouard Monod-Herzen, Principes de Morphologie Générale (1927). Author’s collection.

In doing this, Dalí’s article aligned with the earlier language of some of Cézanne’s admirers, such as that of Théodore Duret thirty years before (recently retold by Shiff), which reluctantly used the same metaphor: ‘[o]ne could go so far as to say that, in certain cases, he renders his tableau with concrete.’50 Meanwhile, the double metaphor allowed by the mosaic appearance of Cézanne’s pictures, on the one hand, and the thick paint applied to the canvas (like cement trowelled onto bricks), on the other, led to the assessment in Julius Meier-Graefe’s equally favourable publication, celebrating the artist as a ‘barbaric mason’, whose paintings ‘looked like walls rather than pictures’.51 As recently shown by Anthea Callen, such terms were used for Gustave Courbet in the mid-nineteenth century, ‘frequently recurring’ for those like Cézanne who came after him, ‘in criticism of the flat, opaque, masonry-like surfaces of modern painting’.52 They were recycled here by Dalí with the aim of associating their surfaces with building and labour and through that with coarseness and even ineptitude.

But it was not only the painterly pattern-making of Cézanne’s cerebral geometricity that bothered Dalí (though like a clumsy, overworked bricklayer, the artist even messed that up) and which the Surrealist contrasted with the sharply contoured, smoothly painted (more ‘Dalinian’, in short) art of the Pre-Raphaelites, redolent, for him, of the geodesic curve described by Monod-Herzen’s book.53 No, he also objected to the lack of volume in his painting, dictated by Cézanne’s ‘accidental’ ambition, in the later words of Greenberg, to ‘give the picture surface its due as a physical entity’.54 Dalí drew a distinction between that and the corporeal presence and sensuous heft of the massy, tightly clothed Pre-Raphaelite women, appreciating them beyond any mere narrative. He spoke of them thrillingly as ‘terrifying’, situating an erotics on ‘the Adam’s apples of Rossetti’s luminous beauties’ as in Beata Beatrix (c. 1864–70, figure 1.8), which Dalí reproduced with his text and which had years earlier provided the inspiration for The Great Masturbator (1929).55 Dalí’s article lends itself to any number of psychoanalytic readings, predictive as it is of the heavy, consoling maternal bodies that René Magritte would muster in his art from 1943 in a Brussels under occupation, and of the later interpretations that art historians would devise of Renoir’s large nudes, both of which I turn to in my next chapter.

Figure 1.8 Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Beata Beatrix (c. 1864–70). Oil on canvas, 86.4 × 66 cm. Tate Gallery, London. © Tate, London 2018.

The mid-1930s was the period of Surrealism’s and, specifically, Dalí’s most intense attack on abstract art. Once pointed out, that historical context reveals that Dalí’s and Greenberg’s remarks emerge from competing attitudes towards abstraction, but a shared understanding of the causal role played in its rise by Cézanne.56 And even if we go only some way (not all the way) along with Greenberg’s later observation that ‘[l]oyalty to his sensations’ led Cézanne into ‘disregarding the texture, the smoothness and roughness, hardness and softness, the tactile feel of objects and seeing colour exclusively as a determinant of spatial position’,57 we can still easily comprehend Dalí’s ‘hypermaterialist’ contrast of that artist’s ‘inedible’ apples with the too-real ‘carnal concretions of excessively ideal women, these feverish and panting materializations’, producing ‘the same effect of terror and unequivocal alluring repugnance [sic] as that of the soft belly of a butterfly seen between the luminescences of its wings’.58 We can also take in just how opposed in its preference such psychoanalytically inflected, Surrealist pictorial analysis was to the high modernism to come and why Greenberg, perfectly aware of Dalí’s one-of-a-kind contributions to art criticism, would himself make a comparison between Pre-Raphaelitism and Surrealism in which neither came out well, in the hypnotically repudiatory essay written a few years later that consigned most of Surrealism to ‘academic’ status and refused to take Dalí seriously.59 Fascinated by the often curvaceous structures of art nouveau, Dalí had already declared himself the first artist of the époque de mou in Minotaure in 1934, so what he saw as the erasure of the supple erotic body at the expense of the physicality of medium in Cézanne’s painting did little to recommend itself to his innovative interpretations, which were as heavily directed by psychoanalytic theory in their form as in their content.60 Indeed, the point is that here are two different methods of writing on art – not two different kinds of art – that turn on interpretation by means of the psychoanalytic body, on the one hand, and visual sensation, on the other. Therefore, the question Dalí inadvertently raised was: might the interpretation of Cézanne, too, be turned from visual sensation and go all the way down to the unconscious?

Still in the year 1936, Breton was pulling together the texts that would soon be published as his third (non-anthologized) major book Mad Love. The main purpose of this poetic, theoretical tract was to give a Surrealist account of the ways in which love, as the most powerful concrete representative of unconscious desire, can be the luminous guide by which people can comprehend the partly conscious and partly unconscious motivations that lie behind everyday events, relationships, behaviour, acts, decisions and coincidences. It maintains that this is love rooted in eroticism, exceeding the common, sentimental, socially and psychologically delimited version of love. If the signposts it creates are followed, it can give the same remarkable access to ways of understanding the world and the mind as dreams and magic.

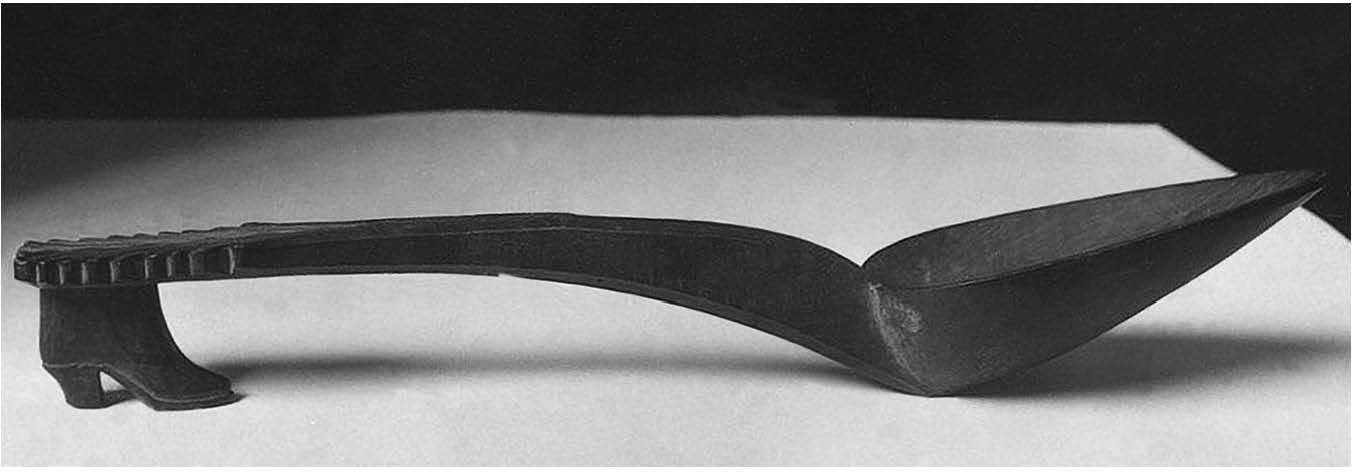

The two most repeated anecdotes in Mad Love are meant to illustrate this and can be sketched briefly. In the third section of the book, Breton detailed a visit he made with Alberto Giacometti to the flea market at Saint-Ouen to the north of Paris, where both men buy objects to which they are powerfully attracted: a large wooden spoon with a small shoe at the end of the handle for Breton; a metal, slatted mask for the eyes and nose for Giacometti (figures 1.9 and 1.10). Breton interprets them in the way Freud had treated dreams, as condensed, manifest material, the latencies of which bespoke, in both cases, inner erotic necessity. The discovery of the two objects was determined, he maintained, by unconscious wishes on the part of the poet and the sculptor to address and overcome obstacles related to love.61

The second, equally well-known episode appears in the fourth section of Mad Love and is that of Breton’s first encounter and euphoric nocturnal stroll in Paris with his future wife Jacqueline Lamba on 29 May 1934, followed a few days later by his rediscovery of his 1923 poem ‘Sunflower’, which he re-read as a point-by-point precognitive account of the events of that evening.62 Breton drew attention to these two incidents in Mad Love to argue that the strength of feeling associated with love heightens the events, relationships, objects and so on that surround it, making them perfect analytical material for fathoming the capricious orbits of the mind. Like much of Breton’s work, the whole book is an attempt to salvage predestination as a material possibility that can be understood as the province of poetry and not as mere superstition or a fantasy of magic, corroborated through events heightened by love by means of methods and a language developed from psychoanalysis.

Figure 1.9 Man Ray, photograph of ‘slipper spoon’, 1937 (published in André Breton, L’amour fou, 1937). © Man Ray Trust/ADAGP-DACS/Telimage 2018.

Figure 1.10 Man Ray, photograph of mask, 1937 (published in André Breton, L’amour fou, 1937). Collection Man Ray Trust. © Man Ray Trust/ADAGP-DACS/Telimage 2018.

Brought together from a set of essays written (and some of them published) over a four-year period, Mad Love was some way into the publication process when Breton decided to add as section six a further anecdote relating a recent event, which has been barely discussed in the scholarship on Surrealism.63 Concerned with temporary discord in love, ‘a banal theme of popular songs’ as Breton put it, this section of Mad Love is situated in Lorient on the southern coast of Brittany where his parents lived, and where he was holidaying as usual in the summer of 1936.64 On the afternoon of 20 July, a bus sets him and Lamba down at the beach location of Le Fort-Bloqué, about seven miles west of Lorient. The weather is poor, the landscape uninteresting and the married pair bored. When they set off walking in search of some signs of life they are directed towards Le Pouldu, ten miles away, made famous by Gauguin’s time there with Charles Filiger and others in the late 1880s (but not enough by the 1930s for Breton to mention it). As they skirt the monotonous shoreline, Breton’s boredom turns to irritation and he begins uncharacteristically pelting seagulls with stones. The stilted conversation of the fed up couple turns to sullen silence as they approach a building:

Would this day never end! The presence of an apparently uninhabited house a hundred metres along on the right added to the absurd and unjustifiable nature of our walking along in a setting like this. This house, recently built, had nothing to compensate the watching eye for its isolation. It opened out on a rather large enclosure stretching down to the sea and bordered, it seemed to me, by a metallic trellis, which, given the prodigious avarice of the land in such a place, had a lugubrious effect on me, without my stopping to analyze it.65

Some minor squabbling with Lamba takes place as their grim promenade progresses. It is all so dissimilar to the euphoric stroll of the ‘Night of the Sunflower’ recorded in the earlier section of Mad Love, which it is meant to meet dialectically as the abrasive, hidden underside of the harmonious aspect of love. Breton feels a ‘panicked desire to turn back on my steps’ as he crosses a stream in that terrain, believing it is getting too late to reach their destination, then the holiday reaches its nadir as the unhappy couple separate to walk around either side of a small fort, also abandoned.66 Soon after, the barren, deserted landscape recedes, they reach an attractive area of beach, and good contact is resumed. Refusing to accept anything so commonplace as ordinary discord between individuals, Breton insists of those moments, ‘we could only have been under the sway of some delirium’.67

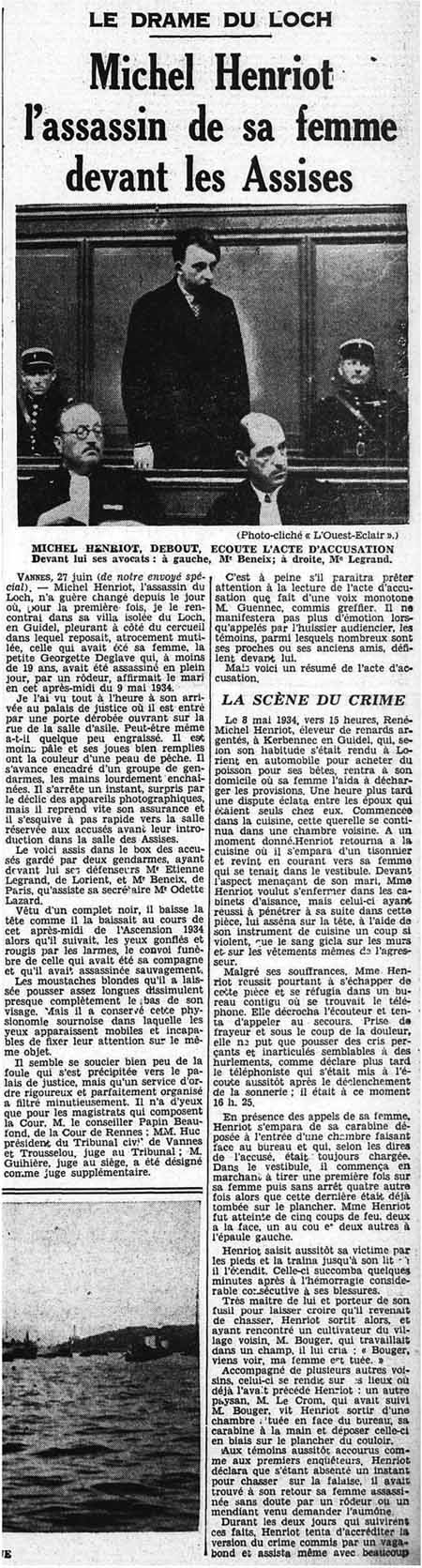

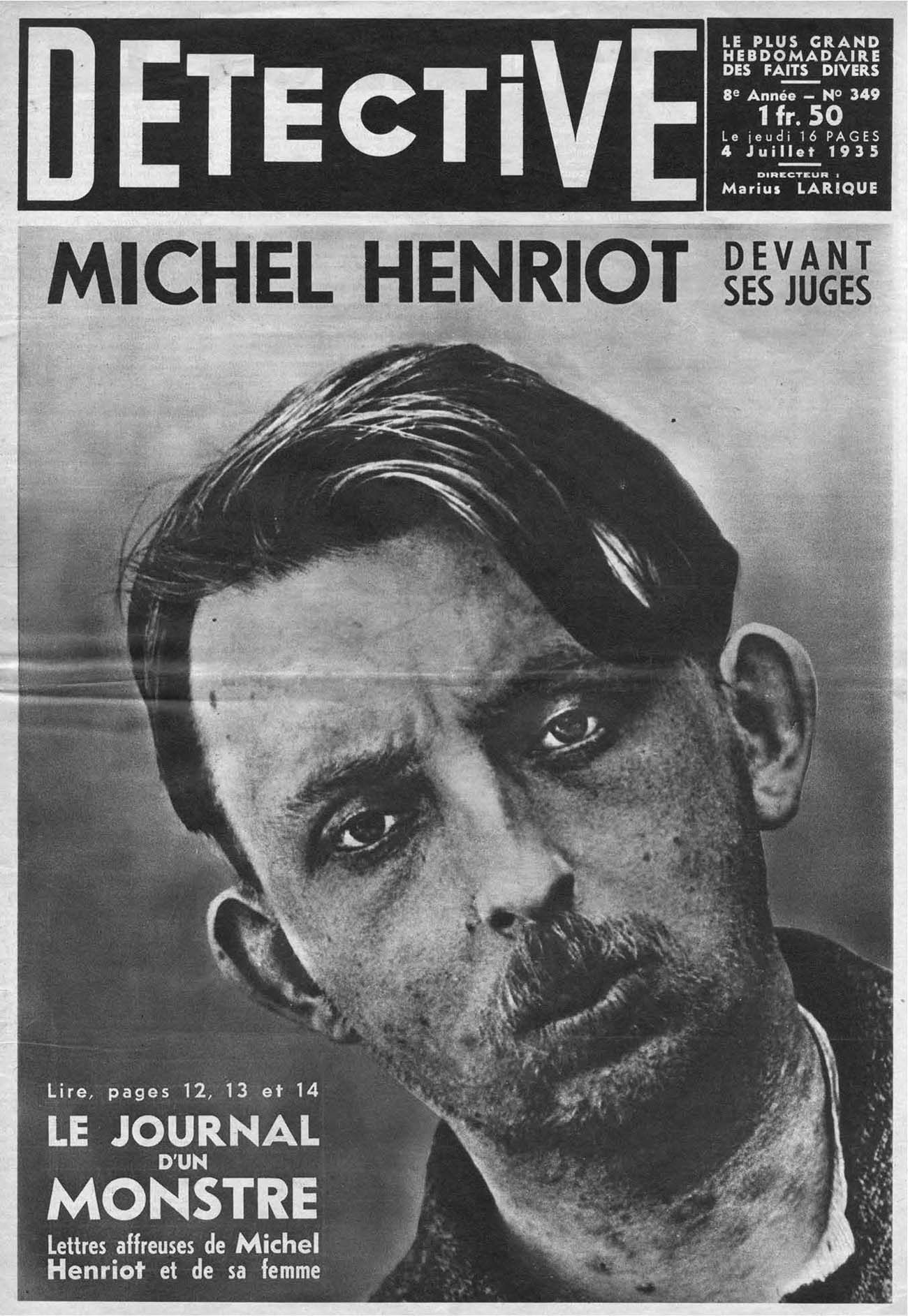

That hypothesis was verified as far as Breton was concerned when he recounted the last few miserable hours to his parents back at their house, at which point his father intervened to remind him that the empty house they passed had been that of Michel Henriot, which lay at the centre of the notorious ‘drame du loch’ (figure 1.11).68 Breton instantly recalled that banal yet spectacular rural incident and its vivid narrative because the trial had been headline or front page news in the local, national, international and specialist press the previous summer (figure 1.12):

Figure 1.11 L’Ouest-Éclair, report of ‘the affair of the loch’, 28 June 1935.

Figure 1.12 Cover of Détective, year 8, no. 349, 4 July 1935.

the whole criminal case reconstituted itself under my eyes, one of the most singular, the most picturesque cases imaginable. It had indeed in its time occasioned much discussion. … the exterior appearance of this house, even with the halo I had found myself attributing to it, is so everyday that you could not possibly recognize it from the pictures published in the papers.69

Henriot was the son of the procureur de la République or local public prosecutor of Lorient (figure 1.13). Initially, he suggested to the police that the murder of his wife, Georgette Deglave, on 8 May 1934 by shots from a hunting rifle, had been carried out in his absence by a homeless drifter. Suspicion soon fell upon Henriot when it was discovered that he had taken out a life insurance policy on her to the tune of 800,000 francs should she die before him. Following his peremptory confession under questioning on 11 May (in which he claimed the motivation for the murder was not greed but his wife refusing him sex), Henriot’s parents made pathetic appeals on his behalf at the brief trial of 27 June–1 July 1935. Over the course of those days, it was heard that the marriage of Michel and Georgette was not founded on love but was the outcome of their parents’ desire to bring together two fortunes. Deeply distressed letters sent more or less daily by the unfortunate Deglave to her sister Marie from October 1933 until two days before her fatal shooting were read out in court. Several times they predicted her murder at the hands of Henriot, linked to the insurance policy, by detailing his death threats, physical abuse and neglect of her in favour of the silver foxes he reared.70 This correspondence had no effect whatsoever on her relatives and failed to save Deglave’s life: ‘[a] lovely testimony in honour of the bourgeois family’, concluded Breton.71

All of this set up Breton’s argument that the temporary disenchantment between himself and Lamba was caused by the geographical locale in which these events took place. Henriot’s habit of shooting at seagulls for the pleasure of seeing them die slowly, as reported in the press, was revisited in Breton’s own impatient behaviour of that day. Deglave’s funeral procession led by the sobbing Henriot and attended by most of the townspeople of Lorient (figure 1.14) had initially followed the same lugubrious path as that taken by Breton and Lamba where they first fell into frustrated silence. The acrimonious, blighted liaison in that isolated house built by Henriot after his marriage degraded Breton and Lamba’s loving relationship when they drew near to it. Finally, the ground between the ‘villa of the Loch’ and the small fort, where it was reported that the Henriots had set up temporary home until building on the villa was completed, was for Breton ‘that afternoon such an exceptional place of disgrace’.72

Although Breton reserved judgement as to whether the bleak atmosphere of the area was determined by the murder carried out by Henriot or whether that fatal incident was itself the outcome of a locale previously saturated for some reason and in some way with malevolence, he was in no doubt that the disturbance that entered into the love between himself and his wife was caused by a malicious frequency generated by the history of that part of Brittany. The couple had merely tuned into it innocently and accidentally that unhappy day, no matter, he writes, ‘how medieval such a way of seeing, in the eyes of certain positivistic minds, may seem.’73

Figure 1.13 Dans la région, report of ‘the affair of the loch’, 29 June 1935.

Figure 1.14 L’Ouest-Éclair, report of the confession of Michel Henriot and funeral of Georgette Deglave, 12 May 1934.

Now, in between Breton’s first mention of the Henriot affair in Mad Love and his subsequent detailed report of the crime and its aftermath in the book, comes a sudden and perplexing digression. This is given over to a sympathetic assessment of the painting of Cézanne, an artist usually thought of as reviled by the Surrealists for reasons to do with craft, as we have seen, to which Breton alludes at the outset of his aside:

Here I open a parenthesis to declare that contrary to the current interpretation, I think Cézanne is not above all a painter of apples, but the painter of The House of the Hanged Man [La Maison du pendu]. I insist that the technical preoccupations, which everyone starts to talk about as soon as it is a question of Cézanne, make us too systematically forget the concern he showed, on several occasions, to treat those subjects having a halo [ces subjets à halo] from Murder of 1870, which bears witness to this concern with evidence, up to the [Card] Players of 1892, around which there floats a half-tragic, half-guignolesque menace in every point resembling the one pictured in the card game of Chaplin’s film A Dog’s Life, without forgetting the Young Man before a Skull of 1890, in its apparent conception of an ultra-conventional romanticism, but in its execution extending far beyond this romanticism: the metaphysical unease falls on the painting through the pleats of the curtain.74

Breton joined the exactly contemporary reinterpretation of Cézanne close to the Surrealist group here. Although he did not mention it, he must have had in mind Dalí’s recent broadside against Cézanne’s architectural apples because it had appeared only two months earlier in Minotaure. Still active in Surrealism, Dalí had been pushed to the outer circle of the group over the preceding two years due to his fascination with Adolph Hitler and somewhat ill-judged rendering of Lenin in his paintings (as far as Breton and his friends were concerned), all of which no doubt helped spur Breton’s alternative reading in this digression. By reminding him of the painting by Cézanne in which another death had seemingly taken place, what Breton saw as the ‘halo’ surrounding the former home of Michel Henriot and his wife and the source of his recent tense and uncanny experience, filtered through reflections on violence and chance in a rural setting, nudged him further into rethinking Cézanne within the larger concerns of the Surrealists.75 That is why he inserted these thoughts self-consciously into his book in the most abrupt manner as a kind of textual aperçu. But in Breton’s compressed reading (covering only just over a page) these are implied rather than stated outright, so for clarification I will draw them out here in relation to the main concerns of Mad Love and view them in the ways in which they connect to the experience near Lorient that he describes.

In fact, as Marguerite Bonnet pointed out, the painting by Cézanne that Breton reproduced in Mad Love is not commonly known under the title The House of the Hanged Man but as the less evocative (though not much less relevant to his anecdote) The Abandoned House (La Maison abandonée, 1878–9) (figure 1.15 and plate 1a).76 Although it is not one of Cézanne’s best known paintings, it is certain that The Abandoned House, reproduced in all subsequent editions of Mad Love, is the painting Breton had in mind, because this is the tableau he describes slightly further along:

The House of the Hanged Man, in particular, has always seemed to me very singularly placed on the canvas of 1885 [sic], placed so as to render an account of something else entirely than its exterior aspect as a house, at least to present it under its most suspect angle: the horizontal black patch above the window, the crumbling, towards the left, of the wall on the first level. It is not a matter of anecdote, here: it is a question, within painting for example, of the necessity of expressing the relationship which cannot fail to exist between the fall of a human body, a cord strung around its neck, into emptiness, and the place itself where this drama has come to pass, a place which it is, moreover, human nature to come and inspect. Consciousness of this relation for Cézanne suffices to explain to me why he pushed back the building on the right in such a way as to hide it in part and, consequently, to make it appear higher. I willingly admit that, because of his particular aptitude to perceive these halos and to concentrate his attention on them, Cézanne was led to study them in their immediacy, considering them in their most elementary structure.77

Figure 1.15 Page from André Breton, L’amour fou (1937) showing reproduction of The Abandoned House (1878–9).

The much better-known, entirely dissimilar painting by Cézanne bearing the title The House of the Hanged Man, Auvers-sur-Oise (La Maison du pendu, Auvers-sur-Oise) (plate 1b) – shown in the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874 and at many others since – was dated c. 1873 by John Rewald, while The Abandoned House reproduced in Mad Love was dated by Rewald 1878–9. Right painting, wrong title, wrong date; the house in this canvas prioritized by Breton to demonstrate his thesis that Cézanne had the sensitivity and insight of a seer, a property long claimed by Surrealist poets and painters such as Breton himself, Victor Brauner, Ernst and André Masson, supposedly finely tuned to the disjointed language of the unconscious (or ‘mouth of shadows’ as Breton termed it after Victor Hugo), had nothing to do with hanged men.78 It might have had no sinister aspect at all for all we know. The ‘halo’ reading is Breton’s of this painting, not Cézanne’s of his motif.

What is more puzzling about Breton’s slip on the title and its extension into his interpretation of the painting – even if it does not achieve the same proportions as Freud’s considerably more repercussive gaffe in his essay on Leonardo da Vinci – is that he must have known the heavily worked and textured House of the Hanged Man because in the 1930s it usually hung in the Louvre (it is now in the Musée d’Orsay).79 This is still more the case because at the moment he was in Lorient with Lamba and as he wrote up their ‘villa of the Loch’ experience for inclusion in Mad Love (between 28 August and 1 September), the squarish, grainy painting was on display under its own correct title at the Orangerie in the large 1936 Cézanne retrospective that ran from May till October (correctly dated there 1873).80 The summer exhibition began before he went to Lorient and ended after his return. It could have been a third prompt – alongside the ‘delirious’ episode at Le Fort-Bloqué and the general debate on Cézanne in Surrealist circles – for the peculiar note on the artist slipped into the book in the midst of the Henriot section (the avant-propos in the exhibition booklet by Jacques-Émile Blanche titled ‘Les Techniques de Cézanne’ covers exactly the ground on the artist that Breton thought was most overworked).81

Bonnet has given a reason for Breton’s lapse: The Abandoned House appeared under the title Das Haus des Gehängten when reproduced in the 1918 book by Meier-Graefe, Cézanne und sein Kreis dated ‘gegen 1885’.82 This is the same incorrect year used and title translated by Breton. Since the other three paintings he mentioned in his Cézanne sidebar in Mad Love are all reproduced by Meier-Graefe with the titles and dates he gave, we can assume with Bonnet that this was the reference source he had to hand; either that or its 1927 English-language equivalent.83 Meier-Graefe’s is a far more passionate and sensual Cézanne than is commonplace in the literature on the artist and he is delivered in an elevated prose style. This would have been agreeable to the ‘Romantic’ ear of Breton who, as well as having an extremely high regard for the art and writing of Germany, had a good understanding of the language. Roger Fry, on the other hand, found Meier-Graefe’s ‘rather breathless and involved phrasing’, which had been conscientiously translated, a little too coarse for the English ear84:

One day he considered himself as the chosen, and the next he grovelled on the floor contemplating suicide. A man in search of God whom he does not find, capable of smashing the world if he does not find Him, a Gothic creature. At times one could have taken him for one of the zealous partisans of the Huguenot period. He was possessed by an absolutism of ideas for which no sacrifice was too great; he was dangerously overwrought, naïve to the point of being ludicrous and withal incalculable. What he really wanted remained vague, and his picture did not contribute to supply enlightenment; awkward deformations painted from memory on principle, directed against nature, in opposition to every form of tradition. All that was evident was the intention to give something different from what had hitherto been considered as art. Nothing was less Gothic than the savage form of these pictures. Only his spirit was Gothic, his incorruptible Protestantism, the refusal to learn from others anything which one must find out for oneself, the determination to begin at the beginning and to build the road to heaven with his own hands.85

Overwrought is the word. As well as showing through in such histrionic passages, Meier-Graefe’s day jobs as novelist and playwright are evident in the total absence of visual analysis in his writing; in fact, he rarely refers to actual paintings at all in the book. His Romantic leanings come through in his use of the terms ‘romanticism’ for certain of Cézanne’s ‘black idylls around 1870’,86 and ‘Baroque’ for some of the works of that period such as Murder,87 as well as in the unexpected attribution here of a ‘Gothic nature’ to Cézanne.88 This is as close as the Provençal artist ever came to a German makeover. Breton would have loved it.

As demonstrated by its inclusion within the discussion of the goings-on in Lorient, underlying the near-anthropomorphic metaphor of a hanged man erroneously projected by Breton onto certain details of The Abandoned House – in the decaying wall to the left as we look at the painting and in the air of suspension and semi-concealment carried by the house itself to the right (an argument that might have been strengthened had Breton not limply rendered the beam sticking out of the front of the house, used for drawing hay up into the opening below it, as a ‘horizontal black patch’) – is Breton’s inquiry into the epistemology of chance.89 This is his proposition that unacknowledged feelings might be the causal template for what are thought of as chance events, which tilt an individual’s life one way or another, and their till-now unfathomable relation with place. Inherited from Dada though rooted in Symbolist poetry, the hand played by chance in matters of love, death and violence had long preoccupied Breton. Accordingly, he argued in Mad Love in the language of clairvoyance that the apparently arbitrary cards dealt by life to an individual were in fact susceptible to interpretation: ‘[e]very life contains these homogeneous patterns of facts, whose surface is cracked or cloudy’, he wrote, ‘[e]ach person has only to stare at them fixedly in order to read his own future.’90 As Breton wrote, the idea of ‘objective chance’ within Surrealism lies in incidents recounted in his Nadja (1928) and its first extension into a theory is in Communicating Vessels (1932) where it is closely associated with a statement credited by Breton to Friedrich Engels: ‘“Causality cannot be understood except as it is linked with the category of objective chance, a form of the manifestation of necessity.”’91 This led to Breton’s own definition of chance in Mad Love as ‘“the encounter of an external causality and an internal finality.”’92

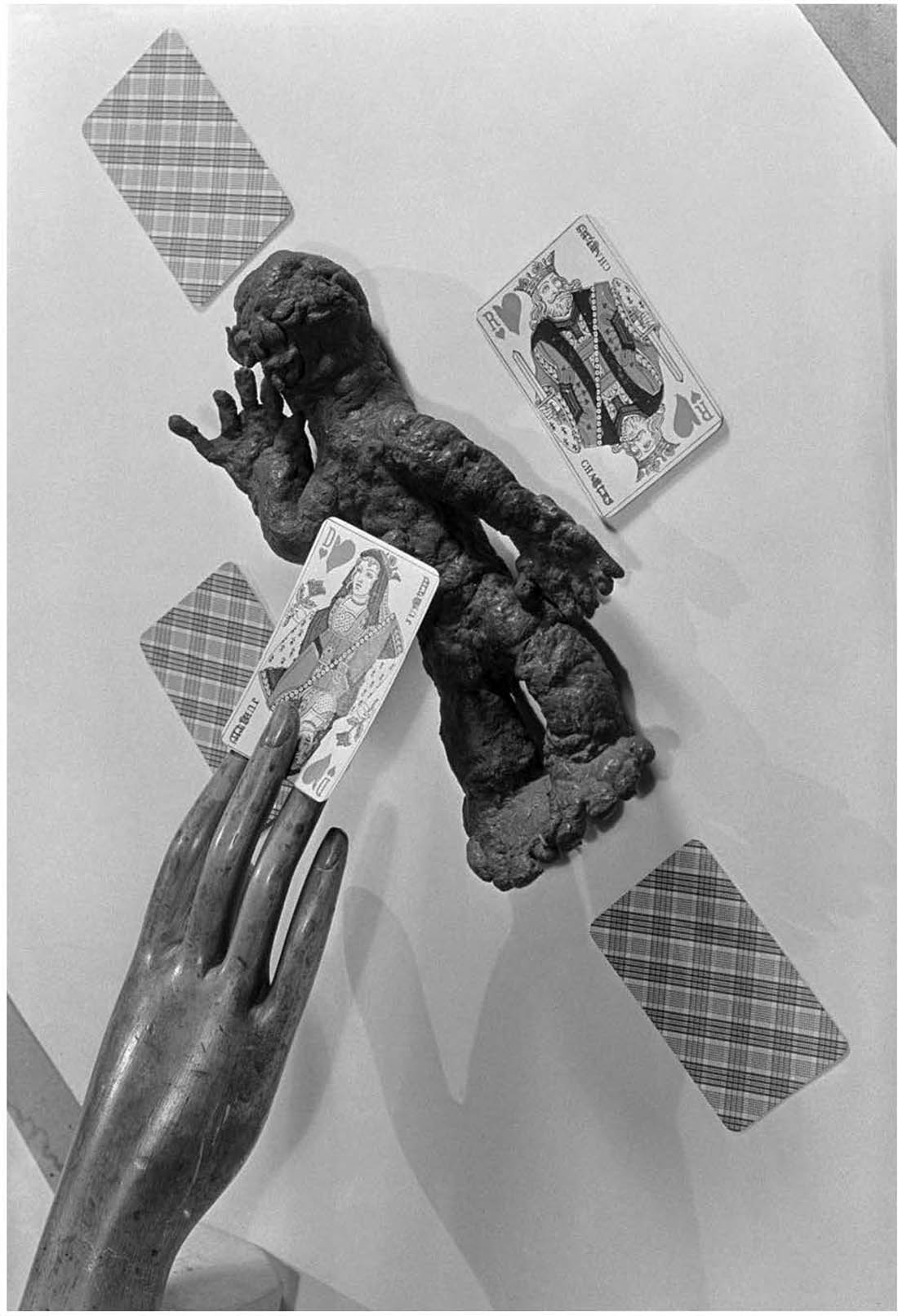

The experience of coincidence and exploration of chance took place within Surrealist art and writing from their beginnings and meant that cards, card games and cartomancy held a particular, ritualistic place of significance among the individual and collective activities that focused the life of Surrealist groups. In Mad Love, Breton described whimsically how some days he sought to fathom the wishes, intentions and movements of women in his life by rearranging objects in his apartment and selecting sentences from books opened at random. ‘Other days,’ he continued, ‘I used to consult my cards, interrogating them far beyond the rules of the game, although according to an invariable personal code, precise enough, trying to obtain from them for now and the future a clear view of my fortune and my misfortune.’93 Sometimes, Breton sought ‘better results’ by including personal items among the configuration of cards, including a small statuette in raw rubber oozing a black liquid with its hand to its ear as though listening (figure 1.16): ‘nothing prevents my declaring,’ he wrote, ‘that this last object, mediated by my cards, has never told me about anything other than myself, bringing me back always to the living centre of my life.’94

Figure 1.16 Man Ray, Myself and her (Moi, elle), 1934 (photograph published in André Breton, L’amour fou, 1937). © Man Ray Trust/ADAGP-DACS/Telimage 2018.

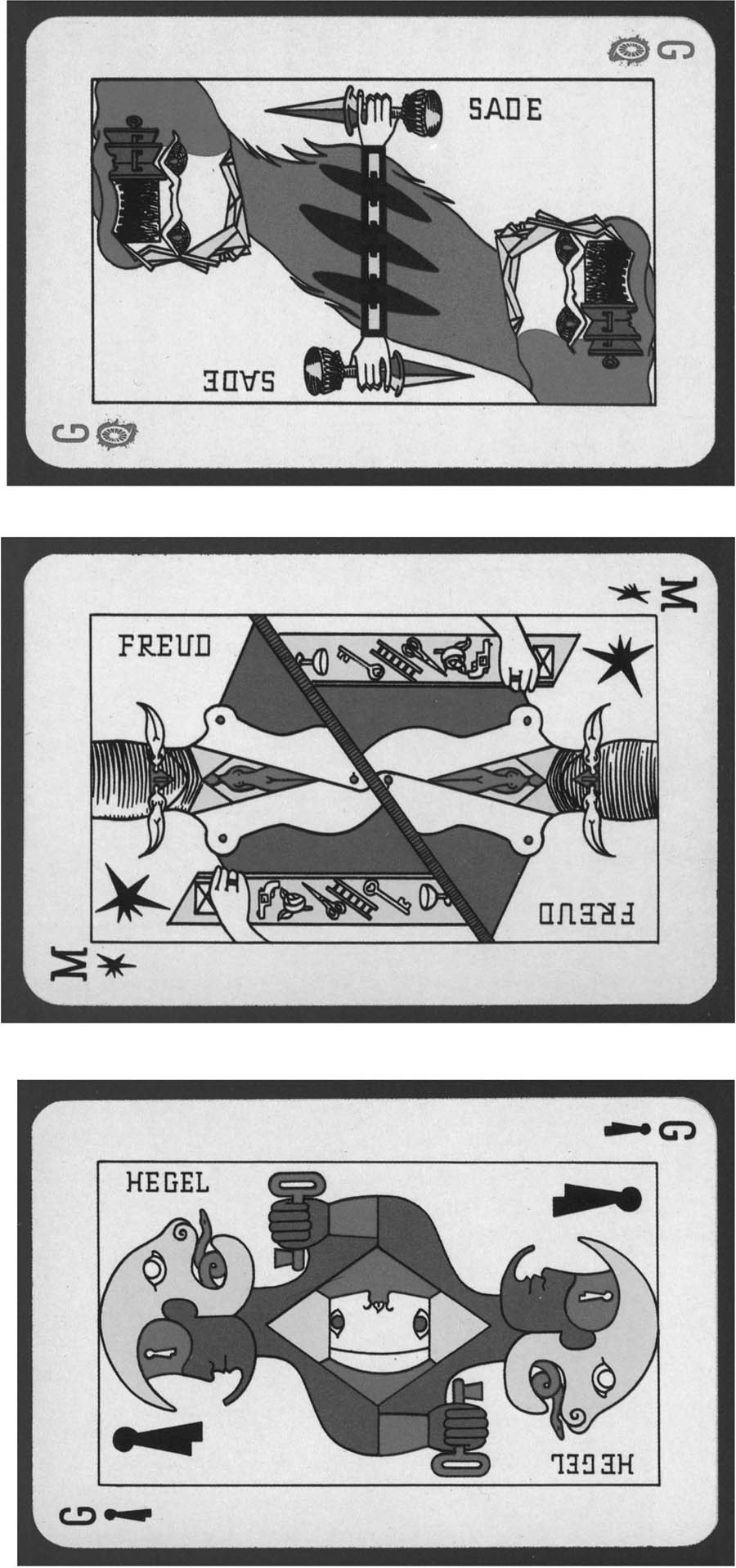

Breton and the Surrealists carried out research on playing cards while in Marseille awaiting transport out of Vichy France between 1939 and 1942.95 The design of their own 1940–1 Marseille cards (figures 1.17 a, b and c) display a coalition of the traditional pack and the tarot (they were partly modelled on the frequently copied, late fifteenth-century Tarot de Marseille). On the one hand, the set retained the structure of the first by replacing the four familiar suits with Love, Dream, Revolution and Knowledge, and the Kings, Queens and Jacks with Geniuses, Sirens and Magi; on the other, it was accompanied by a symbolic language resonant of magic and the occult.96

Figure 1.17 (a, b, c) Cards from the Surrealist ‘Marseille Pack’, 1940–1. Author’s collection.

The Surrealists’ enthusiasm for the poetic properties and divinatory reputation of the tarot had been advertised on the cover of the joint third and fourth number of Minotaure as early as December 1933 when Breton’s by-then former friend Derain, who was familiar with such practices and had read the cards to Breton during their acquaintance (at some point between 1919 and 1921, probably), created a cover that included four tarot cards.97 Later, Kurt Seligmann devoted a lengthy and flatly credulous section of his 1948 Mirror of Magic to the tarot in which he wrote of the seer-like properties of those who read the cards and of the role of the appearance of the tarot in stimulating foresight:

Who has not, even if only once in his life, had that sensation called foreknowledge? Some future event is witnessed so clearly, so plastically, that its beholder knows immediately and with absolute certainty this will happen. And it does!

There are people specially gifted with such prescience or premonition, the born diviners. They stimulate their abnormal sensibility in many ways. Gazing at the crystal produces an autohypnotic condition; in fact, any glistening or colourful object when stared at for a time, may become equally stimulating to the imagination. Some clairvoyant people are able to tell where the stone which they press against their forehead was found. They can describe the landscape in which the stone lay, as well as the person who picked it up, etc.

The primary function of the tarot cards seems to be such stimulation. In scrutinizing the vividly coloured images, the diviner will provoke a kind of autohypnosis, or if he is less gifted, a concentration of the mind resulting in a profound mental absorption. The tarot’s virtue is thus to induce that psychic or mental state favourable to divination.

The striking tarot figures, specially the trumps or major arcana, appeal mysteriously and waken in us the images of our subconscious.98

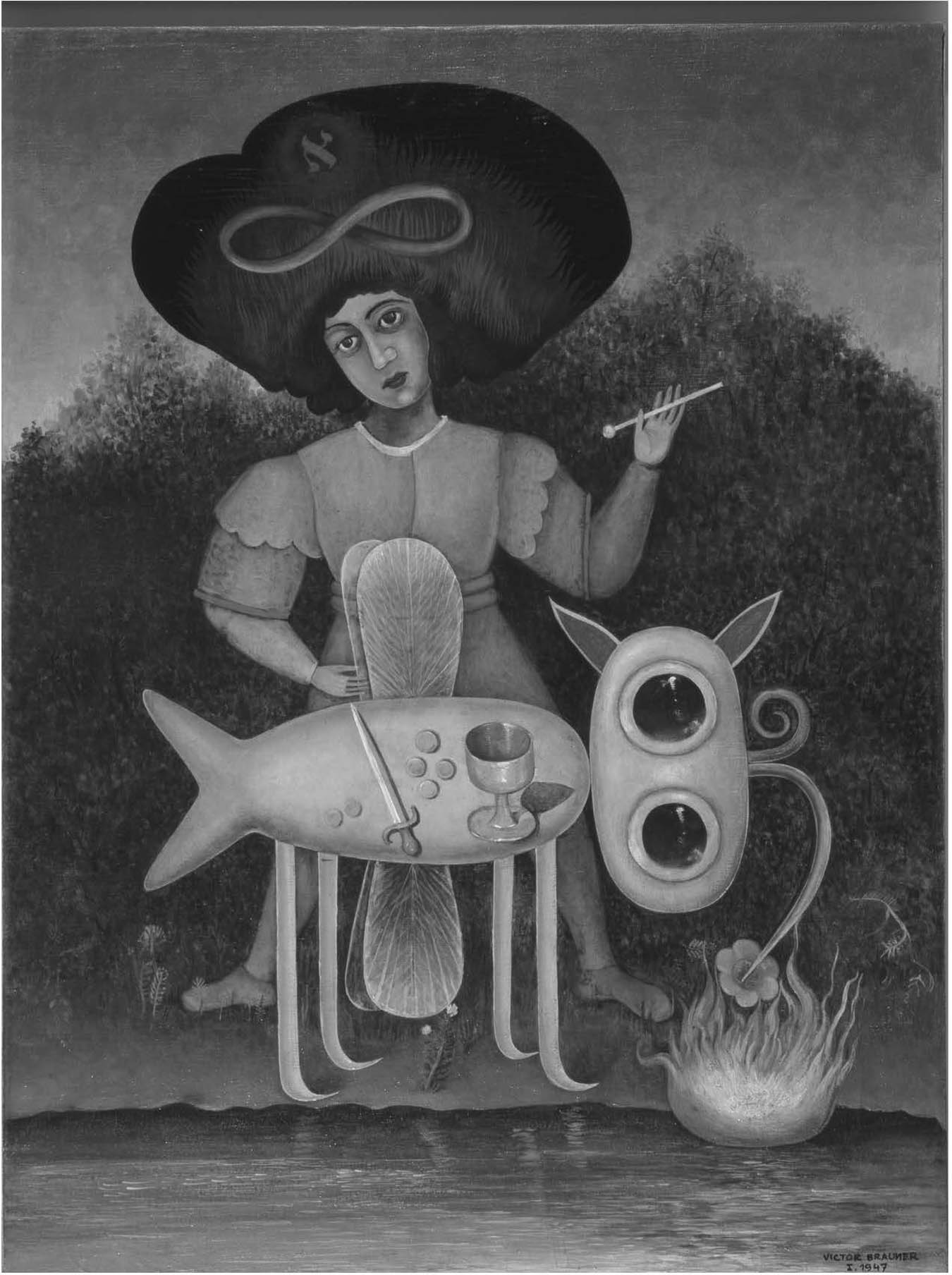

As Simone Perks has suggested, by ‘associating the visions received by the diviner with images of the subconscious, Seligmann gives a Surrealist inflection to divination’.99 If it already sounds like a concoction forcing alignment of magic with Surrealist ideas sourced in psychoanalysis, Seligmann did not stop there, stating further along in The Mirror of Magic that the power of stimulation held by tarot cards made them ‘the “poetry made by all” of the Surrealist postulate’.100 Indeed, the identification between Surrealism and the tarot was so close at that time that Brauner based his painting The Surrealist of 1947 (figure 1.18) on The Magician, Magus or Juggler, the first card of the major arcana (to which Seligmann gave over a subsection of his book), and would paint a symbolic portrait of Breton that year combining that card with the one of The Popess, titling it after the sixth card of the major arcana, The Lovers.101

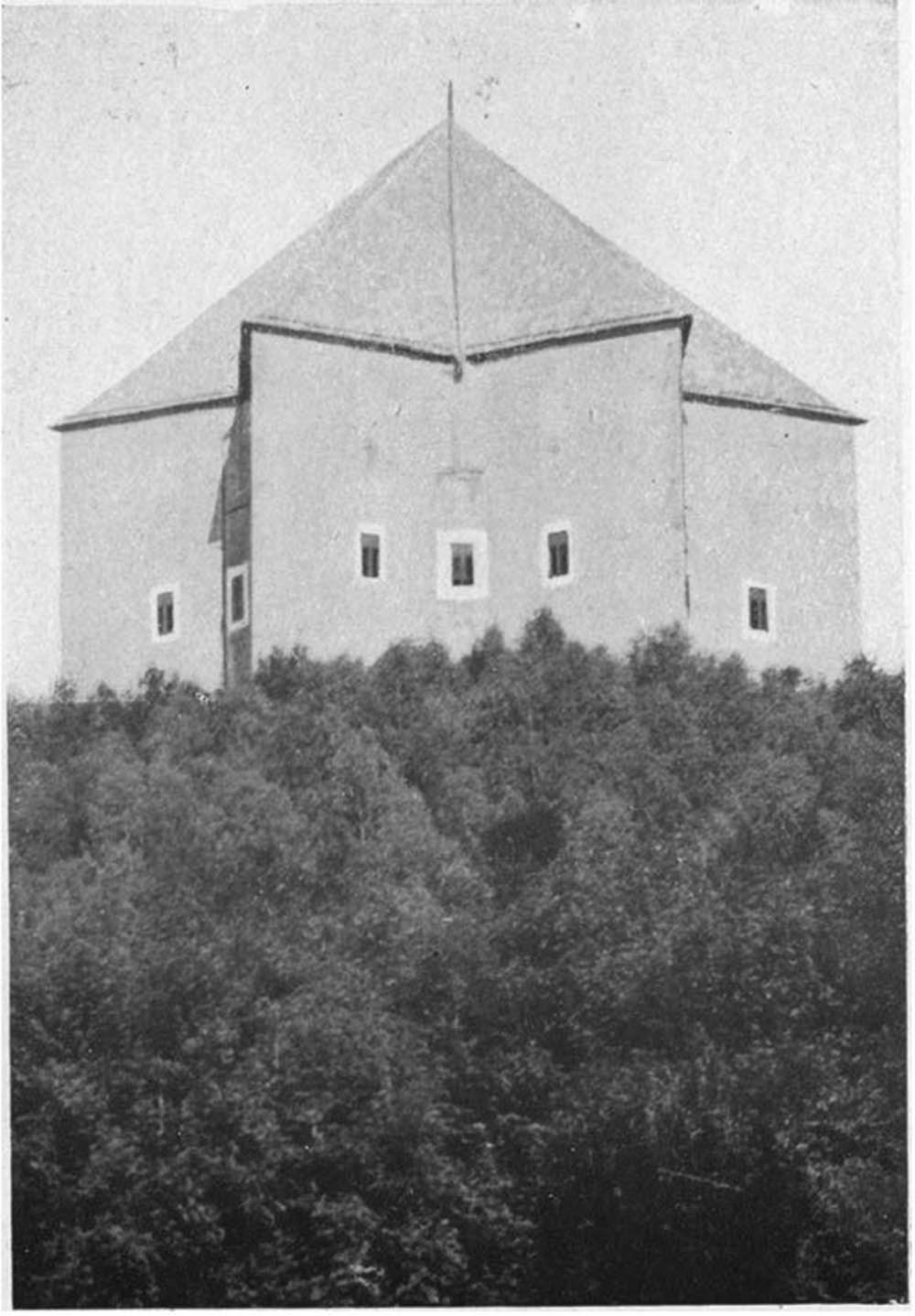

Because Breton had long been interested in divination and the tarot by the time he wrote Mad Love, it is no great leap to the conclusion that his attraction to and interpretation of the painting by Cézanne that he called The House of the Hanged Man was determined not just by an atmosphere evoked by that title, but the enhancement it underwent through its rhyme with The Hanged Man, the twelfth card of the major arcana of the tarot pack, which adds metaphorical layers of gaming and destiny to the painting brought to mind by the Henriot house.102 This is confirmed by Breton’s decision to place the reproduction of that painting back-to-back in Mad Love with the postcard of a building he directly associated with esotericism, the sixteenth-century star-shaped edifice a few miles outside Prague that he had visited in 1935, captioned here ‘A FLANC D’ABIME, CONSTRUIT EN PIERRE PHILOSOPHALE.… ’103 (figure 1.19). The Hanged Man is the most enigmatic card of the tarot (‘in some packs,’ writes one specialist, ‘his head is surrounded by a halo’104) and was reproduced years later in Breton’s L’Art magique on the page facing some examples from the Tarot de Marseille. Breton demonstrated there his reading of the scholarship on the tarot by mentioning the eighteenth-century ‘correction’ of The Hanged Man as Prudence or Man with a Raised Foot (pede suspenso) in the famous essay of Antoine Court de Gébelin.105

Figure 1.18 Victor Brauner, The Surrealist (1947). Oil on canvas, 60 × 45 cm. The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018.

Figure 1.19 Page from André Breton, L’amour fou (1937) showing reproduction of postcard with star-shaped building.

Figure 1.20 Paul Cézanne, The Card Players (1892–3). Oil on canvas, 60 × 73 cm. The Courtauld Gallery, London. © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London.

The themes of chance and fate with which Mad Love is largely taken up, and Surrealism’s longstanding meditation on card playing as emblematic of these, no doubt informed Breton’s characterization of Cézanne’s Card Players (figure 1.20) as one of the paintings among those that were the outcome of a subject with a ‘halo’. Breton could have seen two paintings from the two Card Players series at the 1936 Cézanne show at the Orangerie. One was the 1890–2 New York Metropolitan Museum group of three players watched over by a fourth male, dated 1890 in the Orangerie booklet, and the other was one of the three compositions with two figures of 1892–6, then in the Paris collection of Auguste Pellerin (now in a private collection in Switzerland) and dated by Rewald 1892–3. Well before the Orangerie exhibition, Breton had access to the 1892–3 version of the two-figure Card Players that hung in the Louvre (now in the Musée d’Orsay). Although he did not go into detail (beyond the 1892 date he gave, which I am assuming was taken from Meier-Graefe), as to which Card Players represents the ‘haloed’ subject perceived by Cézanne, Bonnet argues that it was one of the two-figure compositions, ‘due to their background, gloomier and more complex than that of the two other paintings [of three players] where the individuals stand out against a rather light wall, which is hard to place among those works in the category of “subjects with a halo.”’106

This conjecture gains some credence from Breton’s estimation that around The Card Players ‘floats a half-tragic, half-guignolesque menace in every point resembling the one pictured in the card game of Chaplin’s film A Dog’s Life.…’107 As Bonnet notes, this was another error on Breton’s part because although there is indeed a scene in the 1918 film of that title where two men in hats and jackets, one with a moustache, sit opposite each other at a table comparable with the one in The Card Players, upon which, for a short time, a bottle stands between them pushed back towards its farther edge as we look, there is no card game (figures 1.21 and 1.22). This is the scene in which Charlie retrieves the wallet that two thieves have stolen from him by knocking one of them unconscious and performing his gestures to his partner from behind by shoving his arms beneath those of the comatose thief while concealed by a curtain. Given Breton’s frequently expressed fascination with the curtain as a metaphor, we might assume that his remark about the other painting with a ‘halo’ subject by Cézanne, the Young Man before a Skull, in which ‘metaphysical unease falls on the painting through the pleats of the curtain’, was the memory trigger that brought that not very menacing scene from A Dog’s Life inaccurately back to his mind.108

Therefore, if we accept that Breton was thinking of one of the two-figure Card Players in his discussion of the ‘menace’ that surrounds the ‘halo’ paintings, and if we can say further that his main reference source was the German version of Meier-Graefe’s book, then we can add that it was probably the Courtauld Card Players that Breton found disquieting, for that is the version reproduced there (oddly, the English language version reproduces a different Card Players, the one then in the Pellerin collection, which was also shown at the Orangerie and reproduced in the exhibition booklet).109

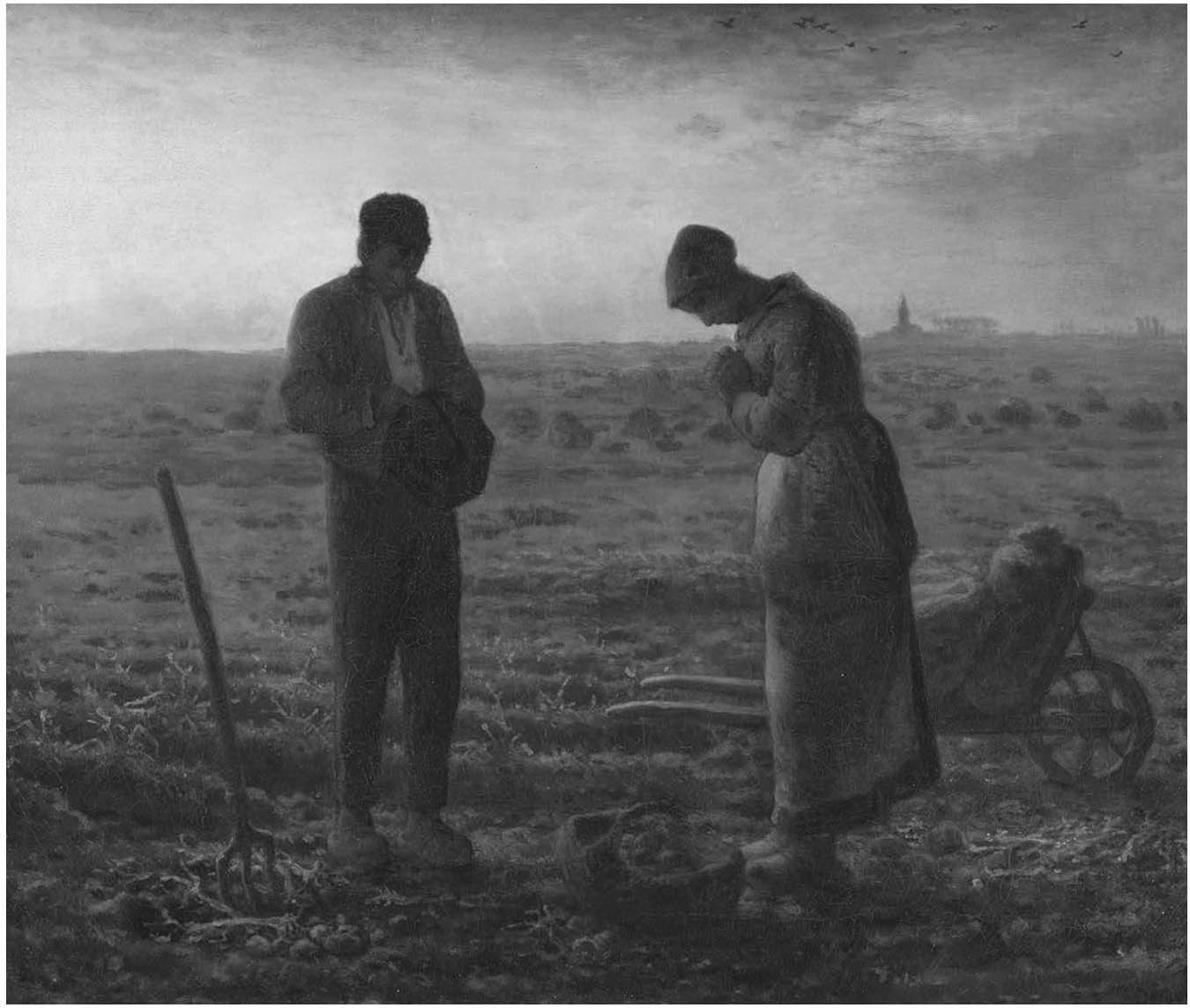

I want to argue in conclusion that it is the two-figure composition and ‘innocent’ rurality of the Card Players, whichever version of the painting we choose, that is relevant to Breton’s interpretation of the picture. I mentioned earlier that his temporary rethinking of Cézanne in the 1930s responded to Dalí’s recent pronouncements on that artist’s apples in his essay on the Pre-Raphaelites in the same number of Minotaure as Breton’s own article on desire and love (framed by his visit the previous year to Tenerife, soon to become part five of Mad Love).110 But there was another source for Breton’s volte-face: Dalí was concurrently poking around in the supposed depths of Jean-François Millet’s pious, sentimental image of rural labour, The Angelus (figure 1.23, 1857–9) and coming up with plenty to talk about. Attracted to the ‘bad taste’ of The Angelus and its endless reproduction on postcards, tea sets, cushion covers, ink wells and so on, which obscured the original painting behind a screen of over-familiarity, Dalí aimed his Oedipal reading of The Angelus at the simpering admirers who crowded around it, exposing the lurid underside of the painting’s manifest drama as though he were turning a stone over with his foot. Freely layering interpretations across The Angelus through associations that accrued to his own anxieties and childhood memories, dipped in the developing fluid of Freudian psychoanalysis, Dalí reached the extravagant conclusion (heavily abbreviated here) that the two figures are praying over the corpse of their buried son; moreover, he added that the female figure to the right of the Angelus is a cannibalistic maternal variant of Saturn, Abraham, William Tell and others, who, in the manner of the praying mantis, is about to devour her son to the left, who anticipates this in a state of arousal that is concealed, in Dalí’s reading, by the hat he holds.111

Figure 1.21 Screen capture from Charlie Chaplin, A Dog’s Life (1918). © Roy Export SAS.

Figure 1.22 Screen capture from Charlie Chaplin, A Dog’s Life (1918). © Roy Export SAS.

Figure 1.23 Jean-François Millet, The Angelus (1857–9). Oil on canvas, 56 × 66 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. © Photo Josse/Scala, Florence.

Most importantly, however, in his quest to show that an offensively inoffensive painting could be taken by the Surrealists and turned to their own purposes – carried out in his writing about The Angelus and also in the ten or so oil paintings he completed between 1929 and 1935 that refer to it, as well as his 1934 etchings illustrating Les Chants de Maldoror – Dalí blended Millet and Lautréamont:

No image seems to be capable of illustrating more ‘literally’, in a more delirious way, Lautréamont and, in particular, Les Chants de Maldoror, than the one done about 70 years ago by the painter of tragic cannibalistic atavisms.… It is precisely Millet’s Angelus, a painting famous all over, which in my opinion would be tantamount in painting to the well-known and sublime ‘fortuitous encounter on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella.’ Nothing seems to me, indeed, to be able to illustrate this encounter as literally, in as horrifying and ultra-obvious a way, as the obsessive image of The Angelus.112

Breton read those words in the booklet that accompanied the exhibition of Dalí’s celebrated Maldoror illustrations in 1934 at the Galerie Quatre Chemins. No doubt he had stayed abreast of the artist’s outlandish findings on The Angelus up to then, which were first aired in Minotaure in 1933 (some of Dalí’s etchings were reproduced in the joint third and fourth number of the review under Derain’s tarot cover at the end of that year and others appeared when the collection was advertised for sale in Minotaure in 1934).113

A profound, violent tension undercut the seemingly modest, becalmed attitudes of the peasants in The Angelus in Dalí’s interpretation. It was the same just-hidden menace that impressed itself on Breton in the emaciated, caricatural features of the Card Players against the background of his recent memory of the murder near Lorient, as though one player were about to eviscerate the other. Breton had no intention of following Dalí in seeking a narrative, psychoanalytic or otherwise, of the relations between Cézanne’s peasant card players or in other paintings by the artist; he states clearly enough that his interest in The Abandoned House/The House of the Hanged Man ‘is not a matter of anecdote’.114 Yet Dalí’s discovery that even Millet’s paintings might harbour ‘hallucinations and sensory disturbances in the shadows’,115 and that ‘good so nicely brings out evil’116 – the terms the younger Breton had used to privilege Lautréamont’s writing over modernist art like Cézanne’s – must have made him realize in the midst of his later discussion of chance and divination in Mad Love, just for a brief moment in 1936, that a Surrealist interpretation of Cézanne-as-seer was possible over that of greengrocer or bricklayer, and had to go all the way down to the unconscious.117

1André Breton, ‘Ideas of a Painter’ [1921], The Lost Steps [1924], trans. Mark Polizzotti, Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1996, 62–6, 64 (translation slightly modified). Whether Cézanne’s ‘reputation’ dimmed or not depends on whether we take Breton to mean by this his fame or his influence, for as late as 1946 he could speak of the artist as ‘le mieux connu de tous les peintres modernes’, while reporting ‘l’influence de Cézanne a été très largement prépondérante en France de 1906 à 1918’, André Breton, ‘Conférences d’Haïti, III’ [1946], André Breton, Oeuvres complètes, vol. 3, Paris: Gallimard, 1999, 233–51, 237, 238.

2Breton, Lost Steps, 64.

3André Breton, Conversations: The Autobiography of Surrealism [1952], trans. Mark Polizzotti, New York: Paragon House, 1993, 10.

4Breton, Lost Steps, 64.

5Breton, Lost Steps, 64.

6See the brief account of its errant fabrication in André Breton, ‘Artistic Genesis and Perspective of Surrealism’ (1941), Surealism and Painting [1965], trans. Simon Watson Taylor, New York: Harper & Row, 1972, 49–82, 60 n.1.

7For a lengthy interpretation, see George Baker, The Artwork Caught by the Tail: Francis Picabia and Dada in Paris, Cambridge, Mass. and London: MIT, 2007, 99–118.

8The sentiment was shared by all Dadas judging from Max Ernst’s sarcastic remarks broadcast from Cologne the same year in Bulletin D: ‘“That paaynting! Ooo that paaynting!” Je m’en fous de Cézanne’, Max Ernst, ‘On Cézanne’ [1919], Lucy R. Lippard (ed.), Dadas on Art: Tzara, Arp, Duchamp and Others [1971], Mineola NY: Dover, 2007, 125.

9Breton, ‘Francis Picabia’ [1922], Lost Steps, 96–9, 97. Breton was quoting from a letter of 15 October 1922 that he received from Picabia, which was eventually reproduced in Michel Sanouillet, Dada in Paris [1965], trans. Sharmila Ganguly, Cambridge, Mass. and London: MIT, 2009, 444.

10Breton, ‘Characteristics of the Modern Evolution and What it Consists Of’ [1922–4], Lost Steps, 107–25, 117 (translation modified). Breton’s exasperation was recapitulated by Aragon at the end of the decade in the important essay that I mentioned in my Introduction complaining about the ‘success of Cézannism’ and viewing collage as the means by which the pictorial tradition exemplified by Cézanne would be overturned: Louis Aragon, ‘The Challenge to Painting’ [1930], Pontus Hulten (ed.), The Surrealists Look at Art, trans Michael Palmer and Norma Cole, Venice CA: Lapis Press, 1990, 47–72, 55.

11Breton, ‘Characteristics’, Lost Steps, 117.

12Breton, ‘Characteristics’, Lost Steps, 117.

13Breton, ‘Characteristics’, Lost Steps, 117–18.

14Richard Shiff, Cézanne and the End of Impressionism: A Study of the Theory, Technique, and Critical Evaluation of Modern Art, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1984, 132.

15Breton, ‘Characteristics’, Lost Steps, 118.

16The former Surrealist Nicolas Calas must have been thinking of this text when he recalled at the time of Breton’s death: ‘[i]n the twenties he had upset Cézanne’s apple cart’ by means of the prioritization he gave dialectical poetics over traditional aesthetics: Nicolas Calas, ‘The Point of the Mind: André Breton’ [1966], Art in the Age of Risk, New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1968, 100–3, 100.

17André Breton, ‘Surrealism and Painting’ [1925–8], Surrealism and Painting, 1–48, 9.

18‘illustres personnages’, The Surrealist Group, ‘Ouvrez-vous?’ Médium: Communication surréaliste, no. 1, November 1953, 1 and 11–13, 1.

19Breton’s response sounds bored: ‘Non, rien à se dire’, Surrealist Group, ‘Ouvrez-vous?’ 11.

20‘Non, par haine des pommes (J. S.). – Non, parce que j’aime les pommes (A. S.)’, Surrealist Group, ‘Ouvrez-vous?’ 11. As in other Surrealist games, the speed of response was meant to undercut too much conscious deliberation: see Penelope Rosemont, ‘Time-Travelers’ Potlatch’, Surrealist Experiences: 1001 Dawns, 221 Midnights, Chicago: Black Swan Press, 2000, 109–15.

21André Breton, L’Art magique [1957], Paris: Éditions Phébus, 1991, 237.

22See Émile Bernard, ‘Souvenirs sur Paul Cézanne et Lettres inédites (I–III)’, Mercure de France, no. 247, vol. 69, 1 October 1907, 385–404; Émile Bernard, ‘Souvenirs sur Paul Cézanne et Lettres inédites (IV–V, fin)’, Mercure de France, no. 248, vol. 69, 16 October 1907, 606–27.

23Denis’s 1907 essay was republished in Maurice Denis, Théories, 1890–1910: Du symbolisme et de Gauguin vers un nouvel ordre classique [1912], Paris: L. Rouart et J. Watelin, 1920, 245–61.

24Émile Bernard, Souvenirs sur Paul Cézanne, Paris: Société des Trente, 1912; Ambroise Vollard, Paul Cézanne, Paris: Galerie A. Vollard, 1914. Breton, who would use the second of these as a reference source, marked his own maturity at 1913 at the beginning of Breton, Conversations, 3. Also see his remarks about his ‘first encounter with Picasso’s work’ in 1913: Breton, Surrealism and Painting, 116.

25‘la peinture pour elle-même’, Émile Bernard, ‘Paul Cézanne’, Les Hommes d’aujourd’hui, vol. 8, no. 387, 1891, n.p.

26André Breton, ‘Les Chants de Maldoror by the Comte de Lautréamont’ [1920], Lost Steps, 47–50, 47 (translation slightly modified).

27Clement Greenberg, ‘Cézanne and the Unity of Modern Art’ [1951], The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 3, Affirmations and Refusals, 1950–1956, ed. John O’Brian, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1993, 82–91, 87, 86, 87, 84, 85.

28This view of the Surrealists (which sounds perfectly plausible and compares with their prejudice against Henri Bergson) is stated without evidence by Françoise Cachin, ‘A Century of Cézanne Criticism 1: From 1865 to 1906’, London: Tate Gallery, Cézanne, 1996, 24–43, 43.

29Also see Breton’s foreword to this volume in which Ernst is credited with the repudiation of form, ‘in regard to which all compliance leads to chanting the idiotic hymn of the “three apples” perpetrated, in the final analysis, all the more grotesquely for their manners, by Cézanne and Renoir’, André Breton, ‘Foreword’ in Max Ernst, The Hundred Headless Woman [1929], trans. Dorothea Tanning, New York: George Braziller, 1981, 7–11, 10.

30‘rétines maladies’, Joris-Karl Huysmans, ‘Cézanne’, Certains [1889], Paris: Tresse & Stock, 1894, 41–3, 43.

31Shiff, Cézanne and the End of Impressionism, 164.

32Julius Meier-Graefe, Cézanne, trans. J. Holroyd-Reece, London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1927, 59.

33Guillaume Apollinaire, ‘The Cézanne Exhibition: Bernheim Gallery’ [1910], Apollinaire on Art: Essays and Reviews 1902–1918 [1960], ed. Leroy C. Breunig, trans. Susan Suleiman, Boston, Mass: MFA, 2001, 57–8, 57.

34‘l’âme ardente et naïve des artistes du Moyen Age’, Georges Rivière, Le Maitre Paul Cézanne, Paris: Henri Floury, 1923, 130. For medievalism, see especially André Breton, ‘Introduction to the Discourse on the Paucity of Reality’ [1924], Break of Day [1934], trans Mark Polizzotti and Mary Ann Caws, Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1999, 3–20.

35Clement Greenberg, ‘Cézanne: Gateway to Contemporary Painting’ [1952], Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 3, 113–18, 118.

36Maurice Merleau-Ponty, ‘Cézanne’s Doubt’ [1945], Sense and Non-Sense [1948], trans Hubert L. Dreyfus and Patricia Allen Dreyfus, Evanston IL: Northwestern University Press, 1964, 9–25, 11; T. J. Clark, Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999, 140. An alternative and very strange interpretation of the latencies of Cézanne’s painting that was made through the discovery of ‘cryptomorphs’ or hidden faces and rebuses among their unconscious symbolism, which might not have been possible without the art historical scholarship on Salvador Dalí and Ernst, was given by Sidney Geist, Interpreting Cézanne, Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press, 1988; a sceptical rehearsal of one of Geist’s ‘almost Surrealist’ readings of Cézanne’s paintings can be found in James Elkins, Why Are Our Pictures Puzzles? On the Modern Origins of Pictorial Complexity, New York and London: Routledge, 1999, 213–15. Another book that has similar claims about a whole roster of late nineteenth- and twentieth-century artists makes available another means of approaching the relationship between Surrealism and fin-de-siècle art: Dario Gamboni, Potential Images: Ambiguity and Indeterminacy in Modern Art, trans. Mark Treharne, London: Reaktion, 2002.

37Theodore Reff, ‘Cézanne’s Card Players and their Sources’, Arts Magazine, vol. 55, no. 3, November 1980, 104–17, 105.

38Meyer Schapiro, Cézanne, London: Thames and Hudson, 1952, 2. For his later view, that ‘one may suppose that in Cézanne’s habitual representation of the apples as a theme by itself there is a latent erotic sense, an unconscious symbolizing of a repressed desire’, see Meyer Schapiro, ‘The Apples of Cézanne: An Essay on the Meaning of Still-Life’ [1968], Modern Art, 19th and 20th Centuries: Selected Papers, vol. 2, London: Chatto & Windus, 1978, 1–38, 12.

39Lionello Venturi, Cézanne: son art – son oeuvre, two vols., Paris: Paul Rosenberg, 1936.

40Lionello Venturi, ‘Sur les dernières années de Cézanne’, Minotaure, no. 9, October 1936, 33–9.

41Ambroise Vollard, ‘Souvenirs sur Cézanne’, Minotaure, no. 6, winter 1935, 13–16. For the limited powers of the Surrealists to veto contributions to Minotaure, see Brassaï, Conversations with Picasso [1964], trans. Jane Marie Todd, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1999, 32.

42John Rewald, Cézanne et Zola, Paris: Éditions A. Sedrowski, 1936; ‘une nouvelle ère des récherches cézanniennes’, ‘à la base de toutes les publications sur Cézanne’, John Rewald, ‘A propos du catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre de Paul Cézanne et de la chronologie de cette oeuvre’, La Renaissance, vol. 20, no. 3/4, March–April 1937, 53–6, 53.

43‘effort de transformation d’un objet donné’, ‘peinture réaliste d’un sujet imagine’, Roger Caillois, Procès intellectuel de l’art, Marseille: Les Cahiers du Sud, 1935, 22 n. 1.

44Herbert Read (ed.), Surrealism, London: Faber and Faber, 1936, 62.

45Salvador Dalí, ‘Current Topics: Right and Left’ [1927], The Collected Writings of Salvador Dalí, ed. and trans. Haim Finkelstein, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998, 49–50, 50.

46Dalí quoted in Marcel Jean with Arpad Mezei, The History of Surrealist Painting [1959], trans. Simon Watson Taylor, New York: Grove Press, 1960, 219.

47Salvador Dalí, ‘Le Surréalisme spectrale de l’Éternel Féminin préraphaélite’, Minotaure, no. 8, June 1936, 46–9.

48Salvador Dalí, ‘The Spectral Surrealism of the Pre-Raphaelite Eternal Feminine’ [1936], Collected Writings, 310–14, 312 (translation slightly modified).

49‘un échafaudage de nos maçons, rectiligne et orthogonale’, Édouard Monod-Herzen, Principes de Morphologie Générale, two vols., Paris: Gautier-Villars et Cie., 1927, vol. 1, 2–3.

50‘[o]n peut aller jusqu’à dire que, dans certain cas, il maçonnait son tableau’, Théodore Duret, Histoire des peintres impressionnistes, Paris: H. Floury, 1906, 178. See the remarks by Richard Shiff, ‘He Painted’, London: Courtauld Institute of Art, Cézanne’s Card Players, 2010, 73–91, 73.

51Meier-Graefe, Cézanne, 21, 21–2. Also see the extended metaphor in which Cézanne is described painting ‘with the blows of a stonemason’ and that of him building ‘like a child with cubes and bricks’, Meier-Graefe, Cézanne, 40, 59. An article on Seurat by another artist that was almost exactly contemporary with Dalí’s in Minotaure asserts: ‘Cézanne is a mason, masoning, touch by touch, with no plans, only sketches. Great mason, certainly, and great sketches’, Jean Hélion, ‘Seurat as a Predecessor’, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, vol. 69, no. 44, July 1936, 4 and 8–11 and 13–14, 10.

52Anthea Callen, The Work of Art: Plein-Air Painting and Artistic Identity in Nineteenth-Century France, London: Reaktion, 2015, 120.

53Monod-Herzen, Principes de Morphologie Générale, vol. 1, 89–99.

54Greenberg, ‘Cézanne and the Unity of Modern Art’, Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 3, 86.

55Dalí, Collected Writings, 312.