I have shown that Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s canonical status within early modernism was refuted by the Surrealists on the whole, through indifference, while Paul Cézanne’s reputation was given a rough ride by them apart from the brief respite in the 1930s. However, those of Georges Seurat and Paul Gauguin would receive very different treatment within the movement. For much of the remainder of this book, I examine the interpretations of those two artists within Surrealism and expand on them.

A favourite of formalists, modernists and classicists since the 1920s, Seurat seems the far more unlikely candidate at first for retrospective surrealization. Yet in that decade, André Breton had touted the artist’s name with approval alongside that of his favourite Gustave Moreau, those of two other Symbolist-related painters, Gauguin and Odilon Redon, as well as Pablo Picasso’s in the article ‘Distance’ of March 1923 that attempted to identify what Breton perceived as the crisis in art caused by the First World War. This was the return to figuration and craft by artists through their infatuation with the classical tradition.1 Breton also tackled in that text what he called the ‘overly formal research’ in art criticism, especially as that was applied to Cubism, an approach that was just beginning a domination of the reception of Seurat that would last for over half a century.2 That sequestration is now well known, even if the detail of its history has never been fully narrated to my knowledge. The purpose of the current chapter is to demonstrate that there was a parallel Surrealist interpretation of the artist and to contextualize that within the evolution of Breton’s theoretical and critical writings over the same period, arguing for its ultimately dialectical structure.

In the year following that early mention of Seurat, the artist’s name turned up again, more notably for historians, in Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism (1924). This was in the familiar sentence referring mainly to precursors in the visual arts, appended as a footnote to supplement the proverbial list of pre-Surrealist writers that followed the definition of Surrealism as ‘[p]sychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express – verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner – the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.’3 Seurat heads the inventory of painters ‘in the modern era’ whom Breton regarded as close to Surrealism yet ‘had not heard the Surrealist voice’.4 That is to say, those individuals had not obeyed their own inner voice, the one by which Breton detected ‘authentic’ Surrealism, synonymous with authentic writing and art. It is tempting to match Seurat’s proclaimed aim made to the Belgian poet Émile Verhaeren to thwart ‘efforts restricted by routine and dreary practices’5 with Breton’s insistence in the Manifesto that automatism guaranteed its user liberation from the ‘preconceived ideas’ still clung to even by the movement’s precursors.6 However, it could not be clearer that Seurat strayed far from the creative programme posted there.

The techniques or enquiries that characterize Surrealism’s interventions in art at its beginnings in the Manifesto of Surrealism and subsequently as they changed with the development of the movement through the 1930s – the speed, spontaneity and licence one witnesses in the ‘literary’ or poetic art of André Masson and often in that of Joan Miró; the adaptation of or to the unconscious, dream or psychoanalytic theory in that of Giorgio de Chirico, Salvador Dalí or Max Ernst; or the outright philosophical reflection on the nature of words and things that drove the painting of René Magritte even during the period in which he adopted a thin version of Renoir’s brushstroke – must be set against the purely painterly, scrupulous and methodical practice of the artist whom Edgar Degas called ‘the notary’.7 Seurat’s theoretical interests lay less in books of literature, poetry or philosophy than in theories of colour and form more directly yoked to the act of painting. His custom was to create studies of his major paintings, many in the case of the earliest important statements Bathers at Asnières (1883–4) and A Sunday on La Grande Jatte – 1884 (1884–6). Seurat’s first truly perceptive supporter Félix Fénéon wrote in 1886 following the display of the second of these at the eighth Impressionist exhibition of 15 May to 15 June of the ‘deliberate and scientific manner’ of the Neo-impressionists.8 Four years after the appearance of Breton’s Manifesto, Seurat’s friend the Symbolist poet Gustave Kahn testified to the artist’s fastidiousness by recalling that he ‘completed a large canvas every two years’.9

Seurat’s process of painting, then, as much as his preparatory method, was slow and steady. As another friend the Symbolist writer Teodor de Wyzewa recalled soon after his death: ‘[h]e wanted to make of painting a more logical art, more systematic, where less room would be left for chance effects.’10 Even Breton himself would later concede that ‘[n]othing could be more premeditated than his enterprise’.11 Once the extensive studies he made were drafted onto canvas as in the Grande Jatte, Seurat was prepared to ‘sign on to years of probing’ in the words of Richard Shiff who adds rather ominously: ‘[t]he depths he attempted to explore were indeterminate.’12 The darkening mood of Shiff’s phrase opens a passage of a sort into the shadow land of Surrealism. In this chapter, though, it will be necessary to take a scenic route through abstract art to get there, in search of a definition of the ‘Surrealist Seurat’ that the Surrealists themselves were reluctant to give.

The logical, disciplined attention paid by the ‘rigidly proper’ Seurat to his regulated and precise craft, apparently at the expense of intuition and accident, makes all the more remarkable his continual presence throughout Breton’s Surrealism and Painting (1965), where only Marcel Duchamp and Picasso are cited with greater frequency.13 Admittedly, no single essay is devoted entirely to the artist in that volume, yet Seurat’s attendance at all in Breton’s writings on art spanning 1925 to 1965 went against the main current of the art market as well as state-sponsored and popular taste in France for most of that period. This might already go some way towards explaining the enthusiasm shown towards Seurat by the Surrealists. Their proclamations of hostility towards nationalism and the state were frequent and given most fervently and enduringly at the time of the riot at the banquet held for the poet Saint-Pol-Roux in July 1925.14 As detailed by Françoise Cachin, the official evaluation of Seurat’s significance in his own country following his death was subdued in comparison with the recognition of the artist’s achievement elsewhere.15 France finally bought its first Seurats in 1947 (three panels for the Poseuses of 1887–8 purchased at the second, posthumous sale of Fénéon’s collection) and Seurat could be described by one writer as France’s Leonardo at the time of the major retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago early in 1958.16 However, his reputation was still mixed at the official level compared to those of the generation after Impressionism – Cézanne, Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh – towards the end of the period covered by Surrealism and Painting.

In the decades after Seurat’s death, the promotional and critical efforts of his friends Fénéon and Paul Signac, who had been appointed by the family to arrange the artist’s professional affairs with another painter Maximilien Luce, led to few sales of his work in France outside of the circle of his contemporaries.17 In 1900, his family sold the Grande Jatte for 800 francs and Circus (1890–1) for 500 (roughly £2,341 and £1,463 respectively in today’s currency).18 Duchamp’s recollection late in life of the period around 1907 was that ‘Seurat was completely ignored’ by his own friends and acquaintances in Montmartre – ‘one barely knew his name’ – though there is some conflict within the personal and historical accounts of Seurat’s status among artists at the time.19 It is usually conceded that his paintings or technique were admired or even partly emulated by some Fauves in the early years of the twentieth century and by abstract artists, Cubists, Futurists and Purists in the years following the large showing of 205 paintings, studies and drawings at the Bernheim-Jeune galleries from 14 December 1908 to 9 January 1909.20 All of the major works except the Poseuses were displayed at that event, coordinated by Fénéon, who oversaw the exhibition and transaction of contemporary works at the gallery from 1906 till he retired in 1924.

In 1910, Duchamp’s friend Guillaume Apollinaire could still refer briefly and flippantly in his art criticism to Seurat as ‘the microbiologist of painting’,21 but after he read Signac’s republished D’Eugène Delacroix au néo-impressionisme (1899) in 1911 Apollinaire revised his opinion, writing of Seurat as a ‘great painter’ whose ‘importance has not yet been fully appreciated’.22 Later that year in a review of an exhibition from which the artist’s work had been excluded he referred to ‘the great painter Seurat, whose name I wish particularly to emphasize’.23 From that point up to the First World War, Seurat’s status only grew in the estimation of Apollinaire perhaps due to further discussion with his artist friends. Soon he was calling him ‘one of the greatest French painters’24 and ‘one of the greatest painters of the nineteenth century and an innovator whose reputation will grow with the centuries’,25 before bemoaning his absence from the walls of the Musée du Luxembourg in 1914 as part of his ongoing campaign against the conservatism of that institution.26 Apollinaire’s insightful appraisal of Seurat and glowing enthusiasm for the artist were no doubt communicated to his protégé Breton in the three years they knew each other from 1915–18, but his art criticism failed to reconcile a larger audience to the artist. There were no solo exhibitions given over to his art in that decade, no books and only four articles, according to Kenneth Silver.27 As Breton would later complain, the general public in France had greeted Seurat’s art with jeering disdain before the First World War.28

The reputation of Seurat truly reached its nadir among museums and collectors in the 1920s in his own country, at the very moment Breton began to cite him and as his stock began to rise among artists and critics. His work was shown by Fénéon at Bernheim-Jeune again when sixty-two paintings and drawings were hung in a solo exhibition of 15–31 January 1920. Probably because of that event, Apollinaire’s friend the poet André Salmon eulogized Seurat, in a way that would hardly have appealed to Breton, as part of ‘the great tradition’, as a link in the distinguished chain of French classicism that included former Fauves André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck and reached back to the Renaissance via Jean-Dominique-Auguste Ingres, Eugène Delacroix and Jacques-Louis David to Raphael.29

Yet in that decade all of Seurat’s major paintings were sold to collections abroad: Chahut (1889–90) to the Netherlands in 1922 (the Louvre had turned it down in 1914); Bathers at Asnières to England from Fénéon’s collection and the Grande Jatte to America both in 1924; and Young Woman Powdering Herself (1889–90) and Poseuses to England and the United States respectively in 1926. John Quinn had purchased Circus in 1923 on the advice of Duchamp’s close friend Henri-Pierre Roché who acted as the American collector’s European art buying agent.30 Bequeathed by Quinn to the Louvre upon his death in 1924, the painting returned to France in 1927, presumably met by an embarrassed or bemused silence within that venerable institution since the critic Florent Fels marked its homecoming with the words ‘Seurat is unknown to the general public’.31 The absence of all these major works from France meant that as late as 1957 Germain Bazin could lament the impossibility of organizing a Seurat retrospective in that country in spite of his efforts and those of René Huyghe since the war.32 From 1908 to 1928, Parade de Cirque (1887–8) hung around on sale at Bernheim-Jeune with Fénéon in attendance for most of that time.33 Breton must have seen the forlorn masterpiece there because as a teenager around 1910 or 1911 ‘he sometimes stopped to exchange a few words’ with Fénéon according to his biographer.34 He might even have seen it when it was shown in the 1908–9 Seurat exhibition held at the gallery. It eventually followed the Grande Jatte and Poseuses into the welcoming arms of American collectors in 1930.

Only one sale of a Seurat was made in the 1920s in France. That was the sparsely drawn red, yellow and mainly blue oil on canvas sketch for Circus dated 1890–1 (figure 3.1) that had been on display at the 1908–9 show. It was purchased from Fénéon by the fashion designer Jacques Doucet in 1924 on the razor-sharp advice of his young librarian and art adviser, the author that year of the Manifesto of Surrealism, André Breton.35

In spite of the trusted Apollinaire’s advocacy of Seurat, Breton’s quick wittedness and curiosity about the artist who prioritized ‘exacting logic’, as Roger Fry put it,36 are not at all easy to explain in the shadow thrown by the Manifesto across ‘logical methods’, which, according to Breton, were ‘applicable only to solving problems of secondary interest’.37 It is true that in the years after the appearance of the Manifesto, in his earliest extended discussions of art and Surrealism in La Révolution surréaliste (twelve issues, 1924–9), Breton observed Seurat’s deployment of what he called ‘the litho [ce chromo] … used so mockingly and so literally as the basis of inspiration for his painting Le Cirque’.38 The elusive, sardonic humour he and others have perceived there would eventually lead Breton to a theory of the artist inclusive to Surrealism, as I show later in this chapter. Yet to this he added hesitantly in parentheses: ‘it is open to question whether what he is generally considered to have achieved technically in the field of “composition” is truly significant.’39 This doubt was expressed in the face of what was already being lauded as the ‘formal design’ of Seurat’s work. But there is open-mindedness here, as opposed to the incomprehension Breton had conveyed and the tone of outright censure he had chosen a few years earlier in speaking of Cézanne’s reputation. Nevertheless, we are still left wondering along with Breton at this juncture as to where the ‘surrealist’ elements lie in the art of Seurat.

Figure 3.1 Georges Seurat, sketch for Circus (1890–1). Oil on canvas, 55 × 46 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. © Photo Josse/Scala, Florence.

His vacillation over the artist and our own reservations about the task he had set himself are perfectly warranted given the historical evidence. It demonstrates that Breton’s query, first raised in La Révolution surréaliste in 1927, took place in the midst of enthusiasm for Seurat’s work in France by those advancing and defending what Alfred H. Barr, Jr. called at the time, in accounting for Seurat’s prominence at the end of the decade, ‘the so-called neo-classic phase [of vanguard art] of the last ten years’.40 This goes some way further towards making a Surrealist Seurat incomprehensible. Silver has charted the ‘new esteem’ achieved by Seurat’s art with the advent of the classical revival of the 1920s, arguing ‘the degree to which Cézanne was devalued was the degree to which Seurat gained new prestige’.41 There was, for instance, Salmon’s 1920 Burlington article on the artist, written by a critic who thought revolutionary art ‘tended only towards the rediscovery of the ways of Classicism’, and who imagined even Cubism had classical roots.42 Further tributes to Seurat came in the pages of Purism’s mouthpiece L’Esprit nouveau in 1920. A colour reproduction of Young Woman Powdering Herself was used to exemplify the idea insisted upon in the dry statement that opened the first issue of the journal that ‘the spirit of construction is as necessary to create a painting or a poem as it is to build a bridge’ (figure 3.2).43 This was followed by the heavily illustrated article on Seurat in that same number of the journal by the artist Roger Bissière aligning him (and Cézanne) with Giotto, Nicolas Poussin, Jean-Antoine Watteau, Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, David and Ingres.44 Meanwhile, Lucie Cousturier’s 1921 monograph reasonably compared Seurat to Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and in the same breath hypothesized the relationship between the structure of his compositions and those of Greek architecture.45 Amédée Ozenfant compared his composition to that of the ‘old Greek geometers’, claiming his landscapes had ‘the dryness of the great French tradition’, while paying homage in a telling phrase to Seurat’s ‘common sense’ in Cahiers d’Art in 1926.46 Finally, Waldemar George praised his ‘classic style, of a modern sentiment’ in a monograph in popular format on Seurat that Breton owned, and which appeared exactly contemporary with Breton’s tentative note on the artist’s composition when it was reprinted from La Révolution surréaliste in Surrealism and Painting.47

These opinions could be found among the eight monographs and thirty-four articles that accompanied the five solo exhibitions devoted to Seurat in the 1920s.48 They represent a complete revision of opinion of his work among critics and collectors if not yet at the level of France’s institutions and that of the general public. This change of heart registered the mood of a postwar cultural elite in that devastated nation that found in Seurat’s art ‘an image of the world’, in Silver’s words, ‘that they found reassuringly ordered, geometric, and much like the world that they themselves hoped to reconstruct’.49 The awakening to Seurat as a modern classic was perfectly consistent with the artist’s obvious interest in classicism fed by his time at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1878–9, an education that had led to deep suspicion among his own circle of painters.50 However, such features of his art are entirely irreconcilable with Breton’s counter-argument against the shortsighted ideology of clarity, order, reason and progress inherited from the same tradition, which the Surrealists blamed for the war. This was displayed in Breton’s protest of the 1920s aimed in the Manifesto against the ‘absolute rationalism that is still in vogue’, his impatient claim there that ‘experience … leans for support on what is most immediately expedient … protected by the sentinels of common sense’,51 and his advancement of hallucination, fantasy, superstition, the unconscious, dream and the marvellous (‘romantic ruins, the modern mannequin’) as the bases for a new epistemology.52 Breton’s budding enthusiasm for Seurat seems willfully contrary if not perverse in the midst of the conflicting cultural remedies touted in the 1920s that helped recuperate the artist. Indeed, his attitude towards Seurat remained intuitive and largely unexplored in his own writings in that decade. Where might we find a space for Seurat in Surrealism given these incompatibilities?

Figure 3.2 Reproduction of Young Woman Powdering Herself as it appeared in L’Esprit nouveau no. 1, 1920.

The beginning of an answer to this question can be found given accidentally in a 1936 article in the Burlington Magazine by the then-abstract painter Jean Hélion whose work carried occasional glimpses of content indebted to Surrealism but who was closer stylistically to Fernand Léger in the 1930s. In fact, as a founder member of the Association Abstraction-Création set up in 1931, he was more alarmed than anything else at the growing importance of Surrealist painting internationally and, as seen in my first chapter, he had been implicitly subject to derision by Salvador Dalí’s ridicule of Abstraction-Création only recently.53

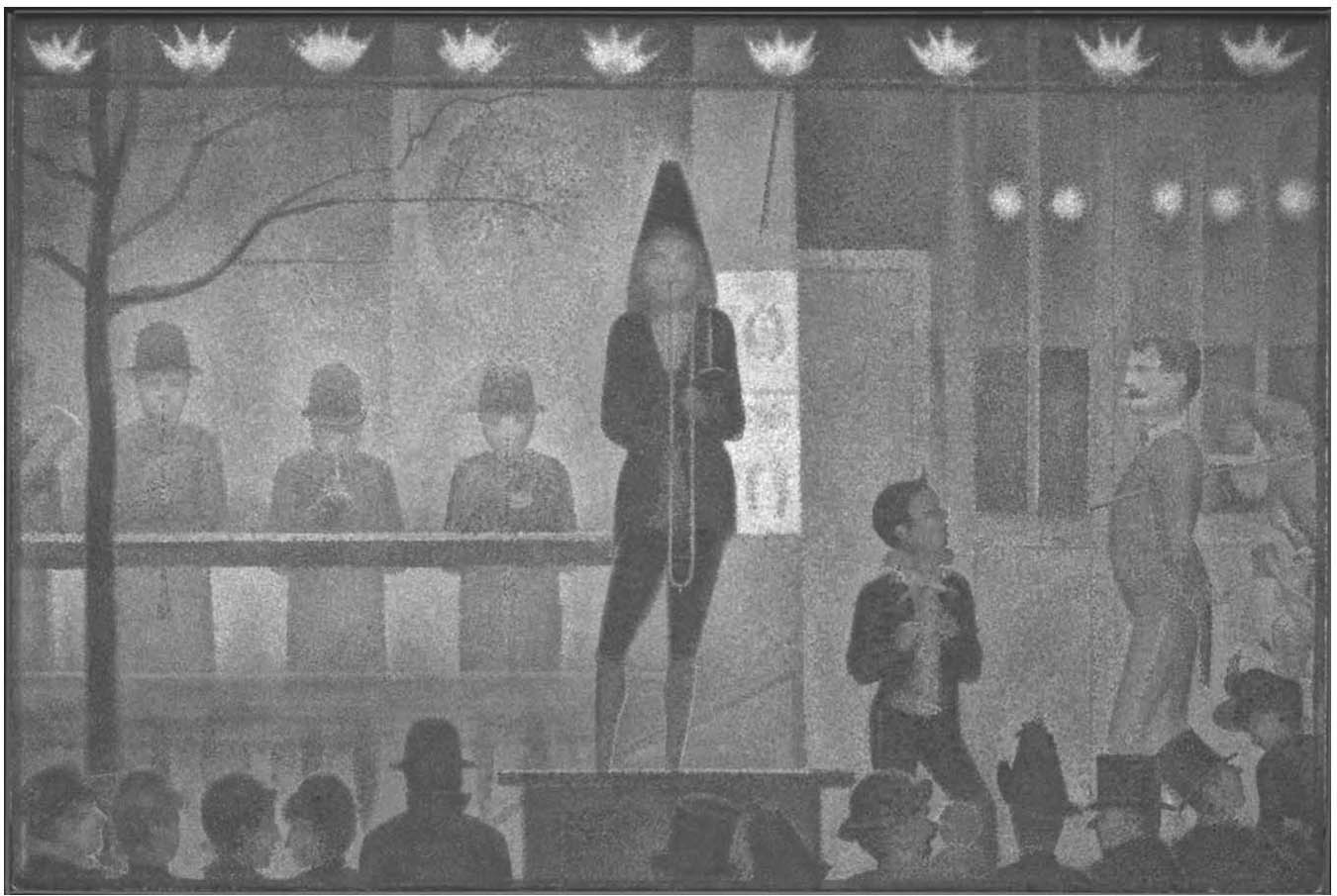

The teleological assimilation of Seurat’s work to abstract art that would be carried out by Hélion was typical of arguments privileging form, abstraction or both and they dominated in the period I am looking at in this chapter. Hélion’s name by no means heads the list of these chronologically. They had begun in the second half of the 1920s when Parade de Cirque (figure 3.3) had been called by Roger Fry ‘as abstract, as universal and as unconditioned as pictorial art ever attained to, at least, before the days of Cubism’.54

Comparable arguments isolating form, style or geometry continued to lead the scholarship on Seurat from the 1930s (with the exception, as we will see, of the writing of Meyer Schapiro). This is evident, for instance, in the schematic drawings of the ‘straight-line’ and ‘curved line’ organization of the Grande Jatte published by Daniel Catton Rich in 1935.55 Hélion’s Burlington article was published only three months after the closure of Cubism and Abstract Art at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York, which featured three small oils and a drawing by Seurat as well as two paintings by Hélion himself, so he might have seen the exhibition.56 He would certainly have known its catalogue, which integrated Seurat into MOMA’s expanding modernist teleology by claiming that his theory of art was ‘as abstract as that of the later Cubists, Suprematists or Neo-plasticists’.57 In later years, Clement Greenberg, Robert L. Herbert and Norma Broude repeated Hélion’s view that the obvious ‘outcome’ of Seurat’s sometimes flattish and caricatural, even cartoon-like style was abstract art in Europe and America, an opinion that was shared in France by the mid-1950s.58 The habit has been hard to break in the years after modernism. In a review of Seurat’s drawings at MOMA in 2008, Yve-Alain Bois attacked this precursor game as ‘seriously flawed’, and even ‘toxic’ and ‘utterly useless’ while outdoing his predecessors by adding a whole roster of European artists to the post-Seurat canon, such as Robert Delaunay, Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian and American ones like Sol LeWitt, Agnes Martin, Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Ryman and Richard Serra (ending his review essay with the inert observation: ‘Seurat, we could say, invented process art’).59

Figure 3.3 Georges Seurat, Parade de Cirque (1887–8). Oil on canvas, 99.5 × 150. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. www.metmuseum.org.

Of course, like those critics and artists who were inclined towards modernism as an ideology, Surrealism, too, would seek to rationalize and strengthen its position by de-specifying itself historically. As I am showing, this was carried out with reference to precursors such as Seurat and Gauguin mainly after the Second World War in the wake of the canonical status achieved by those artists, largely through the efforts of American museums, critics and collectors. Once that historical specificity is returned, modernist abstraction and Surrealism can be seen to inform each other and Hélion’s interpretation of Seurat clarifies Breton’s early, against-the-odds interest in the artist.

Whatever the lines of inquiry it helps extend, the point of Hélion’s article was to give abstract art some historical foundations in earlier modern art by arguing for the pure opticality of Seurat’s work. The spare and orderly painting The Gravelines Canal, Evening (figure 3.4, 1890), for instance, ‘has no other reality than that of its optical existence’, Hélion commented.60 Although it begins by taking elements from the outside world such as boats, a lamp post, the sky, a building, a harbour and anchors, these are only the raw materials for an art that adapts and arranges unstructured nature. These rudiments are taken, oriented, refined, ‘reformed, rebuilt, reconceived’ and ‘written’ for sight, not for the body, Hélion asserted:

Seurat’s picture goes entirely through my eyes. I feel no resistance, no difficulty of accommodation, no need to walk into it. It makes me live entirely through sight. It is organized for sight as a radio-set for waves. Its organization is not like mine, but compatible with mine. It is intelligible, it is within the range of man’s means, of man’s intelligence, the way it has been formed and developed by our culture, a culture that is not natural, but proper to man.61

Figure 3.4 Georges Seurat, The Gravelines Canal, Evening (1890). Oil on canvas, 65.4 × 81.9 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence.

The weight placed on the optical in painting here could not be greater – ‘it makes me live entirely through sight’ – and it seems at first that because of this, equally, such an art could not be further from the ambition held by Surrealism. As I noted already, Breton argued in his first dedicated writings on Surrealism and painting in 1925 that the decoration of the ‘external world’ through painting was a waste of the artist’s gifts. He set out his differences with realism and Impressionism by insisting ‘the plastic work of art will either refer to a purely internal model or will cease to exist’.62 It was exactly the emphasis on ‘mere’ opticality, then, that Surrealism sought to overturn by transforming or re-infusing art with poetics or more precisely with metaphor to create an art not simply of perception but of allusion; one that did not rest as surface pattern on the retina but pointed beyond itself. It was for this reason that Breton did not question Seurat’s actual achievement in supremely gridded compositions such as The Bridge at Courbevoie (figure 3.5, 1886–7) in the same extended essay in La Révolution surréaliste. Rather, he wondered whether that accomplishment mattered. Surely art should be doing something else?

Figure 3.5 Georges Seurat, The Bridge at Courbevoie (1886–7). Oil on canvas, 46.5 × 53.5 cm. The Courtauld Gallery, London. © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London.

Well it turns out that it was through his prioritization of specifically painterly opticality taken to an extreme degree – noted and honoured by Hélion in the context of the abstraction dreaded by Surrealism, ironically – that Seurat achieved this ‘something else’. It was by this process that his painting was nudged by degrees away from external reality and closer to the dialectical surreality that is both derived by the imagination from that material and imposed by the mind upon it. Here is Hélion on Seurat again:

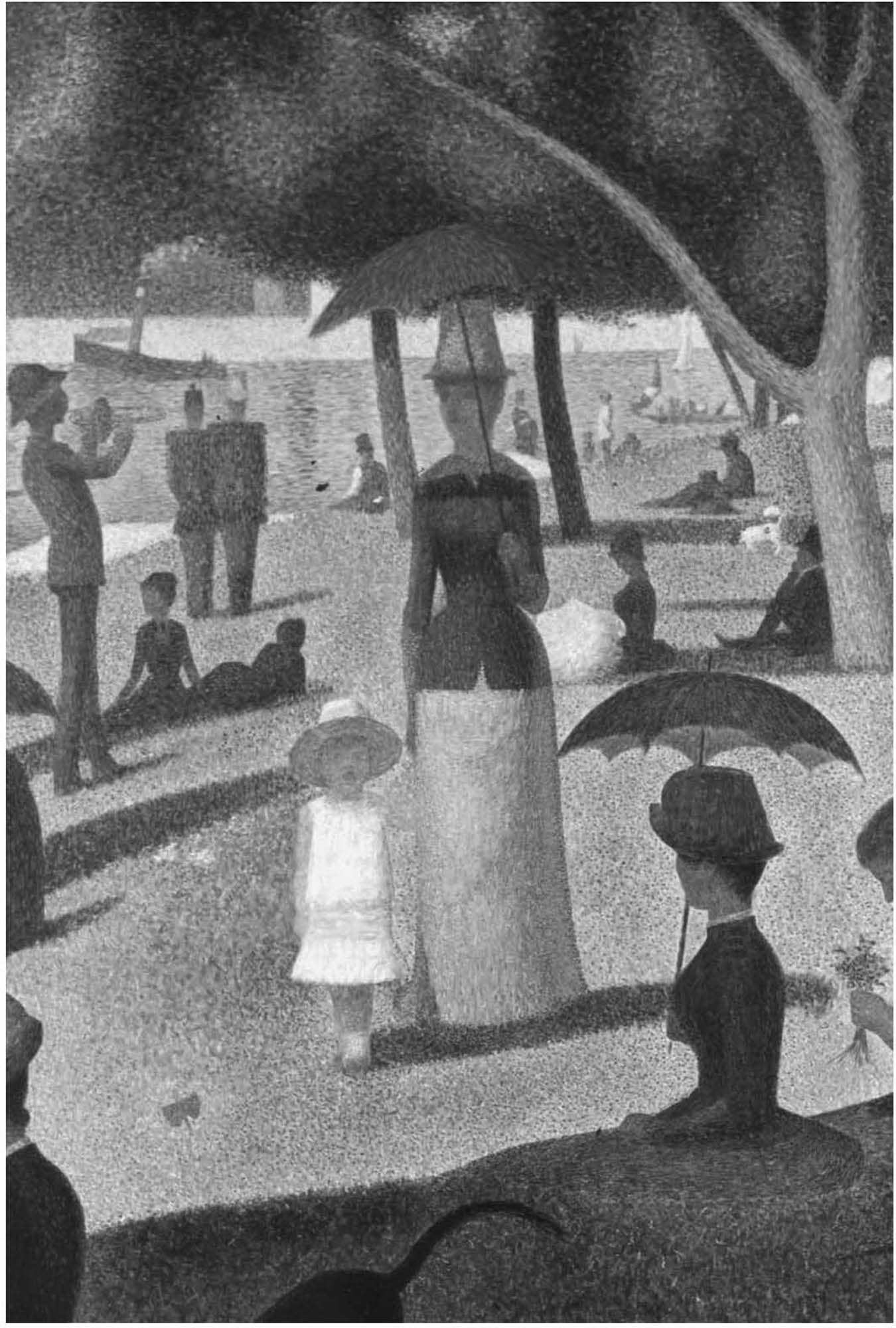

Once he has seized the elements, he stylizes them beyond all resemblance, even to caricature, without consideration for taste, prettiness, normality. The appearance of his picture is never compatible with that of nature. Compared with figures by Courbet or even the deformed figures of Cézanne, Seurat’s personages look like pictures of dummies full of straw. He did not care.… [The figures in the Grande Jatte, plate 5] exist entirely in sight, no more referring to any possible existence outside the picture.63

This excellent description of the purely painterly, non-representational purpose of Seurat’s art is close to Fry’s earlier observation that the ‘syntax of actual life’ in Parade de Cirque ‘has been broken up and replaced by Seurat’s own peculiar syntax with all its strange, remote and unforeseen implications’.64 It strikes me as closer to defining the active–passive procedure his method surely demanded than Tamar Garb’s agenda-driven half-truth that ‘Pointillism posited an authorial subject who was entirely in control.’65 But as Fry lets on here, it is equally if accidentally a definition of the surreal, as another modernist critic T. J. Clark also unintentionally revealed in his Rimbauldian observation that Seurat’s technique ‘show[s] us a world where “Je est un autre.”’66 This was perhaps irresistibly so for Hélion given the ubiquity of Surrealist painting by the time he wrote about the artist in 1936, the year of the International Surrealist Exhibition at the temporary New Burlington Galleries in London and of Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism at MOMA. Hélion was rejecting reference to nature and diminishing the significance for abstraction even of Cézanne, as still too governed by the world beyond the painting – ‘Cézanne looks at the motif. Seurat looks at his canvas’ – and the resulting departure from outer reality achieved by Seurat led to some eccentric results conducive to the Surrealists and their friends.67

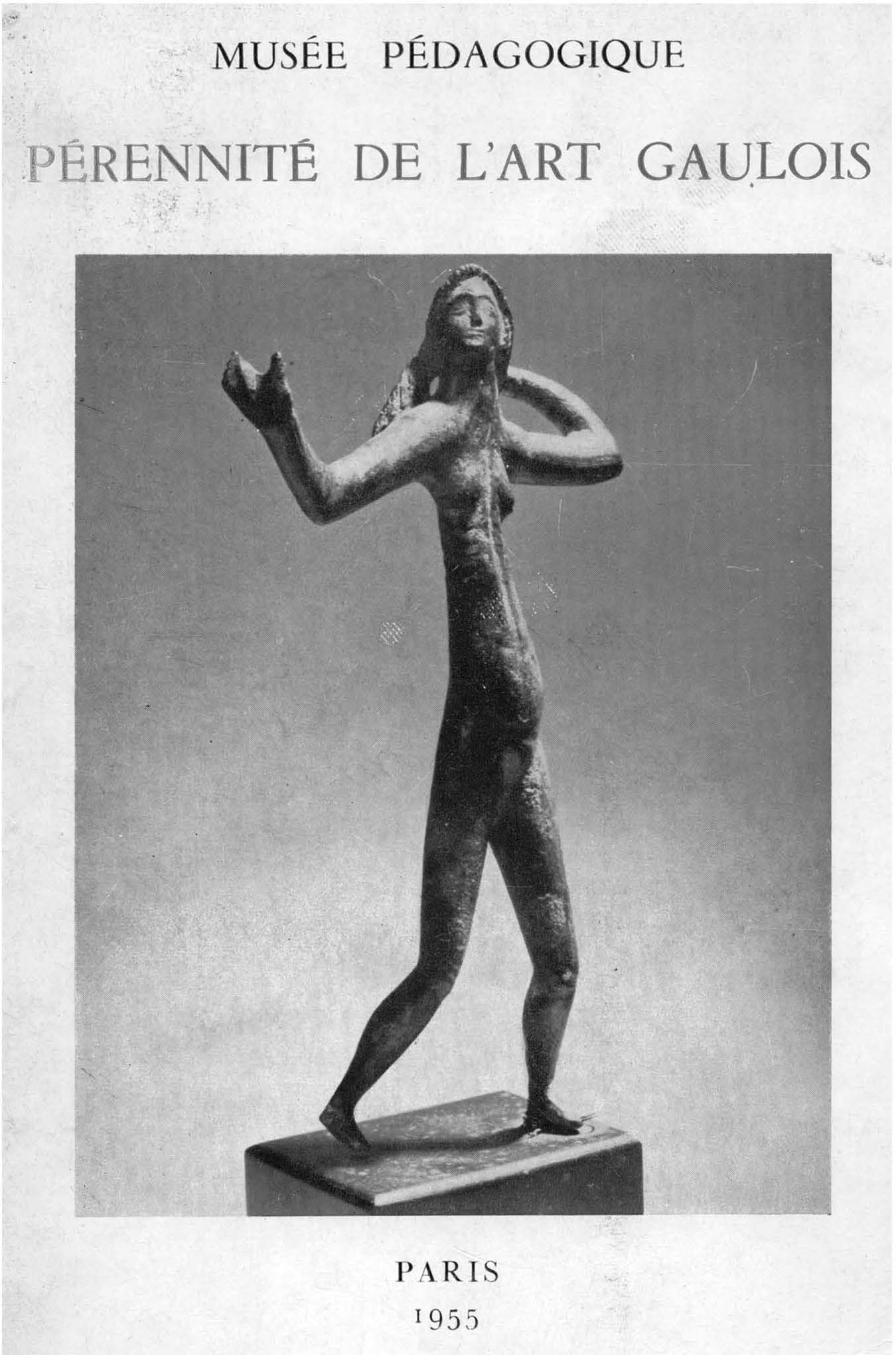

Since Breton’s view on the ‘correct’ subject matter for art did not change substantially over the years – after all, he republished Surrealism and Painting with the same core argument in augmented editions in 1945 and 1965 after its first 1928 outing – we can explore this further by moving forward to the postwar period to look at Marcel Duchamp’s repudiation of ‘retinal painting’ made in an interview in Arts late in 1954, which would become a touchstone for the Surrealists and would be quoted admiringly by Breton in later life. The first time he did this was only a few weeks after Duchamp’s remarks had appeared in print. Breton’s aim was to give some justification for the inclusion of ostensibly motley works in the exhibition Pérennité de l’art gaulois (figure 3.6, 1955) by Impressionists, ‘Post-’ and Neo-impressionists. These included, unusually, Claude Monet (five paintings), Renoir (his Woman Reading of 1874–6 discussed in my chapter on Magritte) and Cézanne (the two-figure Card Players of 1892–3 then in the Louvre), as well as Gauguin, Seurat and van Gogh, and Kandinsky, contemporary abstract artists and Surrealists, alongside the Gaulish coins equally and thankfully free ‘from Graeco-Latin contagion’ in Breton’s words.68 This massive and now-forgotten exhibition was held in 1955 at the Musée pédagogique in Paris’s Latin Quarter, the modern art half of which Breton had helped curate with the art critic and Gauguin specialist Charles Estienne and the expert on Celtic art Lancelot Lengyel. This is what Breton wrote:

The organizers [of the exhibition] thought that it might be fruitful to allow certain aspects of contemporary art to benefit from this very particular scrutiny. The criterion which presided over the choice and presentation of the works of this nature is exactly that which emerges from some remarks made very recently by Marcel Duchamp: ‘Since the advent of Impressionism, the new works of art halt at the retina. Impressionism, Fauvism, abstraction, consist always of retinal painting. Their physical preoccupations – the reactions of colours etc. – put the reactions of the grey matter into the background. This does not apply to all the protagonists of these movements, a few of whom have gone beyond the retina.… Men like Seurat or Mondrian were not retinal painters even though they appeared to be so.’69

Breton was becoming immersed alongside Estienne at the time, not just in Celtic art but in the promotion, partly through the gallery À l’Étoile Scellée, of the abstract art of Jean Degottex (whose February 1955 exhibition at the gallery overlapped with Pérennité de l’art gaulois), René Duvillier, Marcelle Loubchansky and the now entirely obscure André Pouget, as well as others.70 That is why he added a footnote to Duchamp’s designation of retinal painting to clarify what he assumed was the latter’s usage of the term ‘abstraction’, namely, it was meant as ‘the label for a school of art and not in its general acceptation’.71

Figure 3.6 Cover of catalogue for Pérennité de l’art gaulois (1955). Author’s collection.

This is to say that optical painting as figurative art like Seurat’s or even abstract art in the way Hélion had expressed it (if not exactly in the way he meant it) is not retinal. That remains so even if Seurat himself in his notes on artistic method advanced the importance of the ‘synthesis’ of tonal values and colours caused by ‘the phenomena of the duration of the impression of light on the retina’.72 The paintings that result from the method are not mere pattern but are allusive and metaphorical. At the very least, humans are transformed by it into dummies by Seurat (figure 3.7) – archetypes of the Surrealist imaginary – at the most, the world we live in becomes irrelevant to those paintings.73

Figure 3.7 Georges Seurat, detail (of woman and child at centre) of A Sunday on La Grande Jatte – 1884 (1884–6). Oil on canvas, 207 × 308 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago. © The Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY/Scala, Florence.

That is why Breton could also detach Gauguin, Redon and Seurat from Impressionism’s ‘retinal’ opticality a few years later in March–April 1958 on the occasion of the exhibition Dessins Symbolistes by quoting Duchamp’s notion again in order to explain the criticism pitched at such artists by purveyors of colour from Fauvism to abstract expressionism. The latter had long been in the ascendancy in the US by then and Breton probably had its promoters in mind as he wrote these words: ‘it was only to be expected that the belated followers of what Marcel Duchamp once called, with his most disdainful smile, “retinal” art should have reacted extremely violently [against Gauguin, Redon and Seurat].’74 It also explains why Clement Greenberg and Duchamp could use the same language to praise Seurat as a revolutionary yet from entirely dissimilar points of view.75

Duchamp’s own admiration for Seurat is usually explicated by art historians through comparison with the ‘scientific’ aspect of his work and Seurat’s own apparent interest in the science of colour, or through Duchamp’s curiosity about the machine from 1912 alongside the ‘mechanical’ technique of ‘Pointillism’ (as that method was understood by some).76 But Duchamp himself seems to have changed his mind over this. In 1915, he rather grandiosely called Seurat ‘[t]he greatest scientific spirit of the nineteenth century, greater in that sense than Cézanne’,77 before averring much later in the 1960s after a lifetime of iconoclasm: ‘[a]ll painting, beginning with Impressionism, is anti-scientific, even Seurat’,78 at the same time remarking ‘I like Seurat a lot’79 and affirming, as Hélion had, ‘Seurat interests me more than Cézanne.’80 Duchamp and the Surrealists could not have conceded a limited version of Hélion’s argument for Seurat’s opticality, then, the one that made him a retinal painter. They could accept that interpretation only at its most extreme. In the case of Duchamp, who once reportedly proclaimed ‘I have forced myself to contradict myself in order to avoid conforming to my own taste’,81 that extreme was where the rigid truth to opticality built on his method ultimately led beyond the discernment of the eye to the subversion of ‘routine and outmoded practices’, or in the words of Robert J. Goldwater, writing of Seurat, to ‘some means other than his own taste, sensibility, and judgment by which to produce a good work of art’ (or as Hélion put it, ‘he did not care’ where his procedure took him).82 In the case of the Surrealists, that extreme was where his art made contact with another, metaphorical dimension that was indifferent and even blind to the world. It is unlikely that Hélion would have wanted his argument to be taken so far into ‘poetry’, but for the Surrealists there was nowhere else to go.

From here, I want to move towards a major case study in Breton’s later writing where a fully developed dialectical theory of Seurat’s art, which has remained unexamined till now, confirms the dialectical surreality that I have drawn out with reference to Hélion in order to bridge Breton’s early, unformulated interest for Seurat to his later, Duchamp-inspired advocacy. Although he would not have known of Hélion’s 1936 Burlington article, it came at a time that Breton’s interest in Seurat was growing to a noteworthy extent in resistance to the enduring version of the artist as a modern French painter in the ‘classical’ mould of Ingres and Puvis de Chavannes. This understanding of Seurat overlapped elsewhere, and more prominently in English language art history, with formalist accounts of the artist’s significance. By contrast, we can designate Breton’s enthusiasm for Seurat as initially poetic, allusive, metaphorical and analogical. This was registered programmatically and unequivocally in the lecture ‘Qu’est-ce que le surréalisme?’ given on 1 June 1934 in Brussels in which Breton submitted an account of the origins and theoretical development of Surrealism, quoting extensively from publications by the Surrealists including his own Manifesto of Surrealism where the precursor list was amended to reflect his reading of the intervening ten years and his increasing knowledge of art. To that end, Picasso and Seurat were promoted from the footnote to the main text, the former being ‘Surrealist in Cubism’ while Seurat is called ‘Surrealist in design/pattern [le motif].’83

Breton’s interest in Seurat would be unflagging from this point on and well into the 1950s, linked more than once to the similar talented youth and early deaths of established pre-Surrealists the Comte de Lautréamont and Arthur Rimbaud.84 It might have been stepped up in the Brussels lecture due to the exhibition Seurat et ses amis: La Suite de l’impressionisme, which took place in December 1933 and January 1934 at the address of the Gazette des Beaux-Arts on rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré and was accompanied by an article by Signac in that periodical apparently known to Breton judging from textual evidence of the 1940s.85 The title of this exhibition alone demonstrates the new centrality given Seurat in histories of art after Impressionism. Forty-six of his paintings, studies and drawings were shown (though only one major work, Circus) out of 177 in total while presenting the artist as the leader of a ‘school’, confirmed in the introduction penned as a kind of final testament by Signac who would die a few months after the event.86 In addition, Breton must have seen the exhibition Seurat that took place from 3 to 29 February 1936 at Paul Rosenberg’s gallery on the Rue de Boëtie because he owned the slim booklet of the show where fifty-one mainly small oil paintings are catalogued with sixty mature drawings and some other works.87 Furthermore, it is almost certain that he would have seen the massive historical exhibition of French art mounted at the new Musée d’Art moderne in the Palais de Tokyo to coincide with the 1937 Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne titled Chefs-d’Oeuvre de l’Art français in which the Grande Jatte was shown with six other smaller paintings and a drawing by Seurat.

Quite apart from these events in Paris and his growing involvement in art exhibitions, there is another reason for Breton’s enhanced understanding and citation of Seurat in his writings from the mid-1930s. Even though Parade de Cirque had finally disappeared from the walls of Bernheim-Jeune and only Circus was now permanently on display in Paris, he would have uncommon opportunities to view again over the next decade several of Seurat’s major paintings that had been dispersed abroad in the 1920s. He spent at least a fortnight in London in June 1936 organizing and opening the International Surrealist Exhibition, which was only a fifteen-minute walk from the National Gallery where the Bathers at Asnières resides. While in the capital, Breton could also have gone to see the Courtauld collection of Édouard Manet and the Impressionists in Home House at 20 Portman Square where among the Cézannes, Gauguins, Renoirs and van Goghs hung Seurat’s Young Woman Powdering Herself (figure 3.8) (in the front parlour on the ground floor in the early 1930s (figure 3.9) when the permanent collection could be viewed for free on Saturdays).88 Furthermore, while in America during the Second World War, Breton would certainly have seen the Grande Jatte again when he passed through Chicago on the way to Reno in 1945.89

Figure 3.8 Georges Seurat, Young Woman Powdering Herself (1889–90). Oil on canvas, 95.5 × 79.5 cm. The Courtauld Gallery, London. © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London.

Breton’s developed knowledge and increased appreciation of the art of Seurat were aired before his return to Europe from the Americas in the lectures he gave in Haiti in late 1945 and early 1946, mentioned in my Introduction and second chapter. The texts remained unpublished in his lifetime; among them is his major statement on Seurat. Under the guise of an art historian complete with colour slides, Breton imparted a steady, conventional, simplified introduction to modern art since 1880 for a large, professionally mixed audience. His main aim was to provide an overview of the art of the painters who followed Impressionism and to this end Breton gave his lengthiest analysis of Seurat’s work. This would be a dialectical reading and it is signalled initially by a unification of Seurat’s painting with Henri Rousseau’s at the origins of modernism, or, as Breton reasoned it: ‘the modern taste in art fluctuates between an intellectually evolved oeuvre’, such as that of Seurat, and ‘a totally instinctive oeuvre’, like Rousseau’s.90

Figure 3.9 Photograph of the interior of Home House in the early 1930s. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Image courtesy of the Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. © Country Life.

That fallacious appraisal of Rousseau’s sophisticated project demonstrates that Breton’s presentation of early modernism carried as many misleadingly compressed judgements as any university survey course, alongside its expected surrealist biases, omissions and emphases. However, its lengthy passages on Seurat, supported by Breton’s reading of Signac’s D’Eugène Delacroix au néo-impressionisme, were introduced by way of an original thesis that enriches and gives a historico-theoretical rationale based in dialectics for the hypothesis of the abstract-made-surreal that I made earlier in this chapter. Breton approached this initially by asking: ‘what idea is formed, at the beginning, in the sensibility of Seurat?’91 This is his answer:

It is during his military service in a Brittany port at Brest that Seurat assumes, I am arguing, his taste for a visuality of the sea. From that date, in fact, he would opt for the little ports and beaches as motifs. He knew the boat by heart. His correspondence, moreover, bears witness to a complete knowledge of boats:

‘The masts,’ he wrote, ‘are so slender, so fine, so graciously arranged in the air. And those yards that make a cross shape with them at intervals and that rise thinner and thinner and shorter and shorter up to their spindly summits; those lattice tops whose whiteness stands out among the guy ropes, like the wooden part of a harp under these inverted strings; and those thousands of tensed ropes in every direction, from high to low, from starboard to port, from fore to aft, separated, mingling, parallel, oblique, perpendicular, intersecting in a hundred ways, and all fixed, appropriate, tidy, vibrating at the slightest breath of air; all this so harmonious, so complete, so admirably matched in its least details, that a coquette could not invest more art and magic in the sensual arrangement of her evening preparations.’92

Breton takes what he calls ‘an animism’ from this.93 It is surely drawn from the third chapter of Freud’s Totem and Taboo (1913) where animism is associated with magic to this extent: ‘the principle governing magic, the technique of the animistic mode of thinking, is the principle of the “omnipotence of thoughts.”’94 Animism, in this sense, is said by Freud to have survived the succeeding epochs (religious and scientific) in only one field in our civilization, namely, art.

As I noted in my introduction to this book, Benjamin Péret had recently called on both Freud and J. G. Frazer to theorize a modern relevance for magic in La Parole est à Péret (1943).95 Although Breton would bring the relevant chapter from Totem and Taboo to bear on the thorny task of defining ‘magic art’ in tribal societies later on in the 1950s, Freud went unmentioned in his Haiti lecture.96 Rather, he extrapolated this animism of Seurat’s initially by means of an interpretation indebted to ‘mechanical selection’, the notion developed by Le Corbusier and Ozenfant in L’Esprit nouveau arguing that objects constructed by the human hand acquire beauty through their ‘request’ for refinement in their structure as that is determined by their function.97 However, Breton then adds a proviso that draws Seurat in the direction of Surrealist poetics and dialectics:

But this idea, if it were not strongly underlaid by a poetic view of things, would risk leading to an emaciated conception of the work of art, reduced to relying essentially on mechanical progress. Consequently, Seurat, his thought gliding from the boat that drifts far out at sea to the woman devotedly immersed in her mirror in the evening, utters the words magic and sensuality. Magic and sensuality, which are indeed the most valued assets [plus hautes ressources], entail here the intermingling [confondre] on the emotional level of the boat and the woman in their so different attire, the relations between them supporting each other from the fact that the one and the other at that instant help in their better fulfillment of life.98

Whether arguing for a ‘fluctuation’ between Seurat’s intellect and Rousseau’s instinct as the synthesizing movement in the history of modern art, or a ‘fusing’, ‘intermingling’ or ‘merger’ – or even an ‘interpenetration’ to use one of Friedrich Engels’ terms for the operation of the dialectic – of boat and woman expounding a hitherto concealed erotic relationship between the two, it is clear that Breton was seeking a dialectical language here.99 Breton owned the Dialectics of Nature and numerous other volumes by both Engels and Karl Marx. They obviously informed his own conception of dialectics, which is not, however, reducible to their definitions and terminology, especially by the 1940s when Breton was distancing himself from Marxism. Moreover, as is now well known, he had been a close reader of Hegel since at least 1919 and had long been aware of the adaptation of Hegel’s dialectic in a tradition of writing on aesthetics extending from German Romanticism through the work of Victor Hugo and Charles Baudelaire to that of Apollinaire.100

Indeed, Breton’s terminological inconsistency or imprecision might be the outcome of his free recollection of various sources of the dialectical method in social science, philosophy and mysticism. In December 1942, he had stressed the centrality of the dialectic, ‘that of Heraclitus, of Meister Eckhart, of Hegel’, in his lecture ‘Situation of Surrealism Between the Two Wars’ given at Yale University;101 at the beginning of his stay in Haiti, he continued to sponsor ‘true dialectical materialism’ – while ‘reserv[ing] possible rights for the sacred’ – when he welcomed (and perhaps scripted) as an interviewee the poet René Bélance’s statement that ‘Surrealism is the application of dialectical materialism to the realm of art’;102 and he would highlight the importance of dialectics again with reference to his recent discovery of Charles Fourier in the interview with Jean Duché of October 1946 that I referred to in my last chapter.103 In the midst of these statements, we see in this lecture an explicit formulation of the dialectic of Seurat’s art, from the diverse, public, rational and mechanical subject matter of the sails and masts of marines such as The ‘Maria’, Honfleur (figure 3.10, 1886) that ‘interpenetrates’ in Breton’s term with the warm and tender image of the self-absorbed preparation of the coquette, lovingly portrayed in Young Woman Powdering Herself. This is achieved within the scope of Breton’s dialectical notion of ‘convulsive beauty’ theorized in his Mad Love of 1937 – two of the three conditions of which beauty are ‘erotic-veiled’ and ‘magic-circumstantial’, meaning that it arouses passionate feelings and is the outcome of a meaningful encounter (of the kind I referred to in my chapter on Cézanne) – condensing Seurat’s dialectic poetically in a single punning sentence: ‘he knew the boat by heart.’104

Figure 3.10 Georges Seurat, The ‘Maria’, Honfleur (1886). Oil on canvas, 53 × 63.5 cm. The National Gallery, Prague. © DeAgostini Picture Library/Scala, Florence.

There is more to it than this, however. Breton’s main enquiry into the dialectical function of the art of Seurat, inferred from the lengthy passage attributed to the artist, implicitly sustains and is enhanced by its potential extension into a historico-theoretical interpretation of Surrealism’s contradictory aesthetic position to Purism’s, as well as the inner logic of Surrealist art itself. But it only achieves these on the way to its more notable and expansive historical construal of the inner logic of the competing claims on Seurat in the twentieth century between classicism and Surrealism, as I set them out earlier in this chapter.105 Ultimately it even accommodates Seurat’s frequently quoted remark made of literary people and critics to Charles Angrand and much later recalled by Angrand for Gustave Coquiot, which had entertained only one half of the dialectic: ‘they see poetry in what I do. No, I apply my method and that’s all.’106 No, the Surrealist would have countered: your method is the very means by which your work is invested with poetry.107

Breton’s formidable and comprehensive proposal of a dialectical motor driving content, creation and reception of Seurat’s art as well as the historical logic of modern art itself is all the more remarkable for being based on thoroughly erroneous information. Firstly, the quotation he attributed to the artist is not in Seurat’s correspondence, as he thought, but was republished from the writing found among the remaining pages of the notebook he kept during his year of military service in Brest (beginning in November 1879) in the 1924 monograph by Coquiot that Breton owned.108 Secondly, and more importantly, Fénéon had told John Rewald at some point in the years just preceding Breton’s quotation of the passage in 1946 that the descriptions of boats in the notebooks were not Seurat’s own at all but ‘copied by him from some publication’.109 This becomes obvious when its lyrical manner is compared to the telegrammatic style of the artist’s mainly staccato, blunt and factual letters.

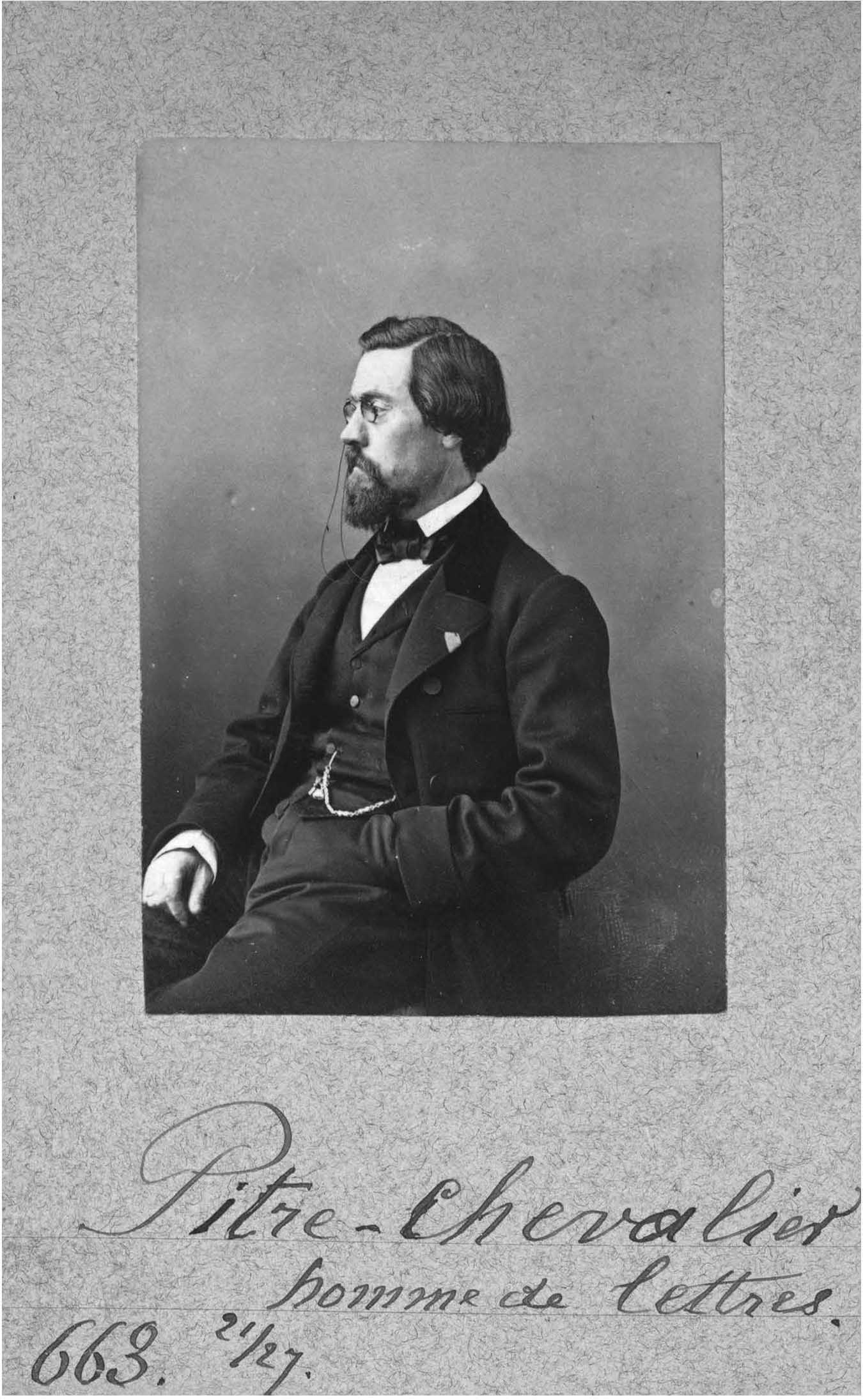

That publication, which has remained obscure to this day in the scholarship on Seurat, can now be identified as the first instalment of the four-volume history of the French at sea, edited and partly authored by Amédée Gréhan and titled La France maritime, which appeared in 1837 and was republished several times from 1848 (figure 3.11). Each volume contained a set of accounts of maritime life, biographical, anecdotal, descriptive or historical, edited by Gréhan to create a general impression of how the French have viewed the experience of the sea. The poetic passage accurately transcribed by Seurat (except for a slight edit towards the end) was taken from page twelve of the first volume and is from a text of three pages, each of two columns, titled ‘Le navire’ (‘The Ship’) and signed ‘Chevalier’.110 This was the work of the journalist, novelist and historian of Brittany, Pierre-Michel-François Chevalier, called Pitre-Chevalier (figure 3.12). Future editor of the popular magazine Musée des familles, where he had written similarly at the time on maritime themes, exploration, colonization, the slave trade and local history (and where Jules Verne published his earliest stories), Pitre-Chevalier knew the history, geography and politics of the north west region and coast of France well.111 He would later author La Bretagne ancienne et moderne (1844) and the weighty tome Nantes et la Loire-Inférieure (1850, co-edited with the folklorist Émile Souvestre). Pitre-Chevalier made further contributions to this first volume of La France maritime as a naval historian under the title ‘Combat du Mars contre le Northumberland, 19 May 1744’ (signed ‘L. Chevallier’),112 and again to the third volume (as ‘P. Chevalier’), the second of which was an essay on Nantes, obviously a trailer for his later book on Verne’s birthplace (it was a hypnotically interesting city for Breton, too).113

Figure 3.11 Title page of Amédée Gréhan (ed.), La France maritime, vol. 1, Paris: Dutertre, 1853. Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon. Image courtesy BML.

Figure 3.12 Photograph of Pitre-Chevalier, Atelier Nadar, 1861. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. © BNF.

Proposing to examine ‘in its details and in its totality, at rest and in action, this marvellous floating machine’,114 ‘Le navire’ is an ornate eulogy to the ship and initially and particularly to the charms of ‘the French schooner’.115 In Pitre-Chevalier’s text it is remorselessly and tiresomely characterized as a dainty coquette:

light, elegant, neatly formed, soaring like a little fish; the schooner with its sheer gently lowered in the middle and raised coquettishly towards the rear like the arched back of a Creole; with all of its harmonious proportion; its elongated shoulders, its sharp poulaine and its hips shaped like a heart above the water. The schooner is the little mistress of our ports; whether she flies on the waves where her wake leaves no traces, or glides and frolics among reefs, she is the swallow of the sea.

A ship such as the brig of Le Havre or of Nantes is less attractive, less elegant, less coquettish than the schooner.…116

Effusive and adoring throughout, we discover that it was in fact Pitre-Chevalier who knew the ship ‘by heart’ not Seurat. We also learn the importance to Pitre-Chevalier of the relationship between utility and beauty in the vessel when, just before he plunges into the passionate accolade that captured Seurat’s attention, he writes of the extraordinarily complex equipment as it meets the eye: ‘each part of this machinery is necessary’, he declares, yet ‘the beauty found there is so intimately linked to utility that at first sight one sees only, in place of design, an elegant coquetry, and one is carried away by the well-groomed appearance of the ship, that which is, above all, for its protection and is its indispensable attire.’117 The argument is so oddly close to Breton’s, given after Le Corbusier and Ozenfant’s on mechanical selection, that it is almost as though the Surrealist read the whole text and not just the fragment copied out by Seurat.

This and the other three volumes of La France maritime are illustrated throughout with etchings of ships of various kinds that frequently demonstrate the delicate complexity of naval equipment that Pitre-Chevalier indicated (figure 3.13). No doubt the book supplemented for Seurat historically and technically the Impressionist imagery of boating on the Seine that he would have known well. But it also introduced him to harbour drawing and etching, the subgenre of maritime visual culture, even though he did not sketch any ships at the time. He would only embark on the marines in 1885 after making his name as a painter of modern life in Paris and at five years distance from his military service, not in Brest but further east along the Channel coast at Grandcamp, Honfleur, Port-en-Bessin, Le Crotoy and Gravelines (all some way north of Pitre-Chevalier’s beloved Nantes). It is not unreasonable to view those paintings as the realization of a long-held aspiration to paint the sea that began while Seurat was in Brest at the beginning of the decade. More confident appraisal of his marines alongside the engravings in La France maritime is enticing and even cautiously rewarding. This is especially the case for comparison of those illustrations with his marine harbour paintings containing ambitious renderings of masts and rigging such as The ‘Maria’, Honfleur and Corner of a Dock, Honfleur (1886). In these, the technical detail of the various boats shows a truer co-existence of industry and leisure than that sought hard for by T. J. Clark in Monet’s 1870s paintings of the river at Argenteuil, one easily associable with the reciprocity of utility and beauty that I just showed Breton extending dialectically into a poetics of the image.118

Figure 3.13 From Amédée Gréhan (ed.), La France maritime, vol. 1, Paris: Chez Postel, 1837. Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon. Image courtesy BML.

It matters little that the poetic passage quoted by Breton was not Seurat’s own; it obviously held some value for the artist and presumably reflected his own feelings since he took the trouble to transcribe it to his notebook and retain it. Furthermore, Rewald, Kenneth Clark and others have made comparable speculations to Breton’s about the formative nature of Seurat’s brief period of military service.119 We might even surmise that the pleasure Seurat took from the elaborate passage stood in for that he normally gained from his artistic practice since he did not paint and sketched little during that year. If Breton’s interpretation made accidentally via Pitre-Chevalier receives substantial weight from the subsequent importance Seurat gave to marine painting, it takes on remarkable resonance for the closeness of the Young Woman Powdering Herself to the description of the coquette found by Seurat and written out by him in this passage. Although Breton does not mention the Courtauld painting in the Haiti lecture, it was obviously on his mind as he expanded the fragment from the notebook into a theory of the artist.120

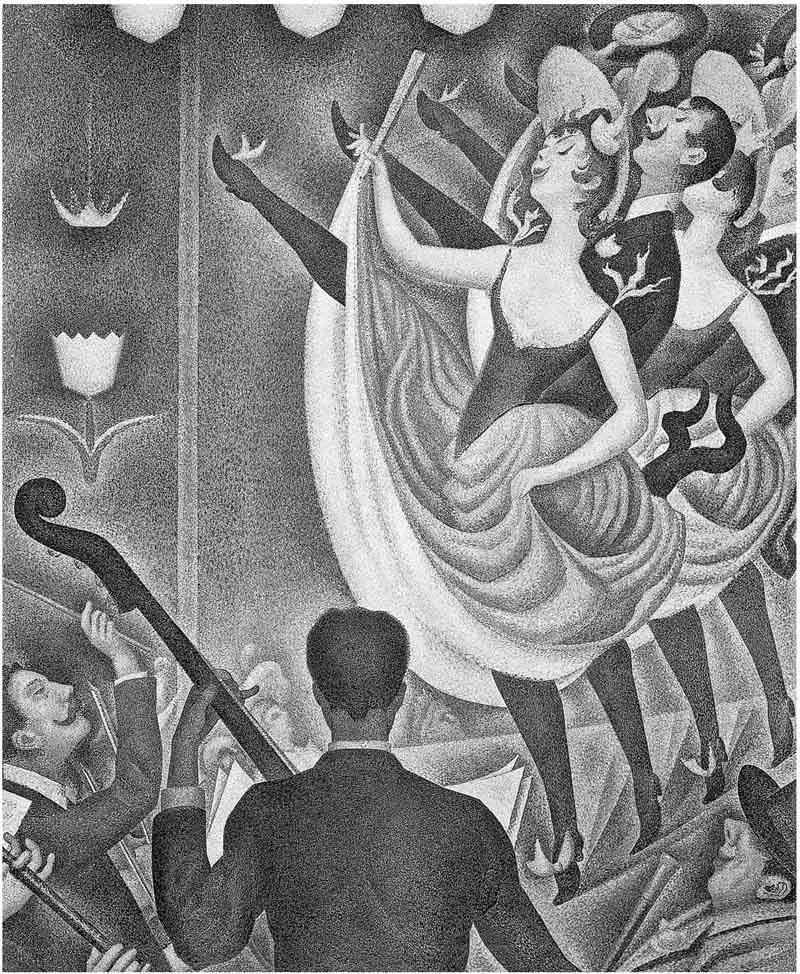

In the Haiti lecture, Breton remained initially within his dialectical reading of Seurat’s painting in viewing Chahut (figure 3.14) as another ‘synthetic conception’ in the sense that it arrested the gestures of the dancers at their very extremity.121 This was in keeping with the third condition of convulsive beauty, ‘exploding-fixed’, where movement expires at its limit, illustrated in Mad Love by the photograph by Man Ray that immobilizes a dancer (figure 3.15).122 Yet Breton broke off because he wanted to pin down the mocking humour he had discerned in Seurat’s work since his earliest writings on the artist in the 1920s, returned to recently in his Anthology of Black Humour (1945). Distribution of the book had been prevented in 1940 by the Vichy government in France and it was just out as he arrived to speak in Port-au-Prince. In the introduction to the Anthology, Breton had referred to art in which ‘humour can be sensed but at best remains hypothetical – such as in the quasi-totality of Seurat’s painted opus.’123 He then examined the humour of Chahut in the 1946 lecture as follows:

Figure 3.14 Georges Seurat, Chahut (1889–90). Oil on canvas, 171.5 × 140.5 cm. Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo. © DeAgostini Picture Library/Scala, Florence.

this painting seems to me to shelter a good many other intentions, which have not yet been aired and make it one of the works whose impact is still in large part to come. Not enough has been made in La Chahut [sic] of its contribution to an icy humour that is entirely modern, which, freezing here impossibly the scene which insists upon the most boisterous treatment, engenders a feeling of extreme vanity and absurdity, corroborated by the inane or blissfully satisfied expressions of one and all.124

Figure 3.15 Man Ray, ‘explosive fixed’, 1937, photograph from André Breton, L’amour fou (1937). Collection Man Ray Trust. © Man Ray Trust/ADAGP-DACS/Telimage 2018.

Figure 3.16 Georges Seurat, detail (of shoe with bow of foremost dancer of) Chahut (1889–90). Oil on canvas, 171.5 × 140.5 cm. Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo. © DeAgostini Picture Library/Scala, Florence.

The ‘exploding-fixed’ humour was extended towards the ‘magic-circumstantial’ through the isolation by Breton of the brightly lit bow on the shoe of the foremost dancer (figure 3.16), which for him was the key component in the composition. He perceived in this bow the ‘entirely poetic heroine’ of Chahut, as a core form insofar as it binds the painting analogically.125 Its ‘wings’ compliment and even reinforce the movement of the dancer’s raised leg; they match the shapes of the upturned corners of the mouths and moustaches of the figures in the painting, as well as the leaves of the tulip-shaped gas jet at centre left; and its colouration harmonizes with the wall lighting. It is as though it were a ‘Will-o’-the-wisp’, in Breton’s words, which ‘communicates to the canvas its exorbitant life’, and it is ‘these elements of great humour and the magic of certain lighting bringing about the strange distribution of organic elements’ that establish synthesis in Seurat’s later work.126 This is a reading Breton extended to Parade de Cirque in which he acclaimed the artist’s rendering of the light of the acetylene gas jets then still in use in Paris and it is one we will see is of value for my next chapter in comprehending the Surrealist reception of Seurat’s drawings.127

It is perhaps not surprising that Seurat’s work was available to Breton’s dialectical reading, nor in that case that those paintings could be esteemed by critics of art who were ideologically diametrically at odds, given the artist’s admiration from an early age for both Ingres and Delacroix and the usually stereotypical ways in which those artists were opposed to each other in the claims made upon them by competing camps of artists and writers. In the early 1960s, Robert L. Herbert hinted at the possibility that Seurat’s exceptional drawings could also be seen in divergent terms, perhaps recalling the presence of the artist’s work at Cubism and Abstract Art. Adopting the art historical language of that period, which just about remained that of his own time, Herbert saw them as each two things:

an arrangement of certain flat forms and a number of illusionary realities which those forms suggest. In the twentieth century, dominated by formalistic considerations, the former has assumed such prominence that our view of the latter has been prejudiced. We delight in investigating the abstract components of art, and too often give a secondary place to the artist’s ties with the tangible world. Because Seurat did not deal in anecdote, because he seldom showed the features of his subjects, he is too readily presumed to have been interested only in form for its own sake.128

While pointing in the direction of a more content-led means of interpreting the artist, Herbert’s subject is not the Surrealist Seurat, naturally. Although ‘illusionary realities’ might be taken to imply a proto-Surrealist sensibility in the drawings, this is then corrected by reference to ‘the artist’s ties with the tangible world’ to designate Seurat the political artist or at least the social historian who painted peasants as ‘simple people of immense dignity, always at work’.129

Written at the time that the challenge to the dominance of formalism in modernist art history was beginning, Herbert’s passage revealed at once the possibilities held by Seurat’s drawings for discussion beyond their formal properties and the suppression of such interpretation by art historians. It also helped make possible later remarks close to Surrealism once the battle had been won, like John Russell’s accreditation of Seurat as ‘a supreme master of the poetic imagination’.130 However, neither Herbert nor Russell was aware that Surrealism had long since reached that conclusion, partly through Breton’s fascination for the paintings, as I detailed in this chapter, but also by means of the surrealization of those peerless drawings. This extended quite beyond their formal geometries, of course, and it was an interpretation less attuned to the local connection with the social world that Herbert thought they made available than to their ‘indeterminate depths’ advertised by Seurat and remarked much later by Shiff. I look at them in the context of Surrealism in my next chapter.

1André Breton, ‘Distance’ [1923], The Lost Steps [1924], trans. Mark Polizzotti, Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1996, 103–6.

2Breton, Lost Steps, 106. His editors allege that it was L’Esprit nouveau, the periodical of Purism, that Breton had in mind here: André Breton, Oeuvres complètes, vol. 1, Paris: Gallimard, 1988, 1321.

3André Breton, ‘Manifesto of Surrealism’ [1924], Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972, 1–47, 27.

4Breton, Manifestoes, 27 n. 1.

5‘efforts vinculés par les routines et les pratiques mornes’, Émile Verhaeren, ‘Georges Seurat’, La Société nouvelle, vol. 7, no. 1, 1891, 429–38, 432.

6Breton, Manifestoes, 27.

7‘Degas appelait Seurat le notaire’, Gustave Kahn, ‘Au temps du pointillisme’, Mercure de France, tome 171, no. 619, 1 April–1 May 1924, 5–22, 13.

8‘manière consciente et scientifique’, Félix Fénéon, ‘VIIIe Exposition Impressionniste, du 15 Mai au 15 Juin, Rue Laffitte, 1’ [1886], Oeuvres plus que complètes, vol. 1, ed. Joan U. Halperin, Geneva and Paris: Librairie Droz, 1970, 29–38, 35.

9Gustave Kahn, ‘Georges Seurat, 1859–1891’ [1928], The Drawings of Georges Seurat, New York: Dover, 1971, v–xiii, vi.

10‘Il voulait faire de la peinture un art plus logique, plus systématique, où moins de place serait laissé au hasard de l’effet’, Teodor de Wyzewa, ‘Georges Seurat’, L’Art dans les deux mondes, no. 22, 18 April 1891, 263–4, 263.

11‘Rien de plus prémédité que son entreprise’, André Breton, ‘Conférences d’Haïti, III’ [1946], André Breton, Oeuvres complètes, vol. 3, Paris: Gallimard, 1999, 233–51, 239. Breton repeats almost word-for-word the phrase of Roger Fry who came late to Seurat a few years before the arrival of Bathers at Asnières at the National Gallery in London: ‘Nothing can be imagined more deliberate, more pre-ordained than this method’, Roger Fry, ‘Seurat’, Transformations: Critical and Speculative Essays on Art, London: Chatto & Windus, 1926, 96, 189. An earlier statement by Fry of 1920 was meant as a personal view of his taste of the preceding decade given in the language of formalism but it was, rather, the opinion of history: ‘my most serious lapse was the failure to discover the genius of Seurat, whose supreme merits as a designer I had every reason to acclaim’, Roger Fry, ‘Retrospect’ [1920], Vision and Design [1920], Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1961, 222–37, 226.

12Richard Shiff, ‘Seurat Distracted’, Jodi Hauptman (ed.), Georges Seurat: The Drawings, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2007, 16–29, 18.

13The phrase comes from Richard Thomson, Seurat, Oxford and New York: Phaidon, 1985, 11.

14The protest against nationalism, xenophobia and colonialism at the banquet for Saint-Pol-Roux is fondly recalled in André Breton, Conversations: The Autobiography of Surrealism [1952], trans. Mark Polizzotti, New York: Paragon House, 1993, 87–9; recorded in Gérard Durozoi, History of the Surrealist Movement [1997], trans. Alison Anderson, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2004, 90–2; and in Mark Polizzotti, Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton, revised and updated, Boston: Black Widow Press, 2009, 210–13. Also see the report of the incident, which includes the main eyewitness and historical accounts, in Raymond Spiteri and Donald LaCoss, ‘Introduction: Revolution by Night: Surrealism, Politics and Culture’, Surrealism, Politics and Culture, Aldershot and Burlington VT: Ashgate, 2003, 1–17.

15Françoise Cachin, ‘Seurat in France’, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Georges Seurat: 1859–1891, 1991, 423–4.

16Germain Bazin, ‘Seurat est le Vinci français’, Arts, no. 654, 22–28 January 1958, 14.

17Joan Ungersma Halperin, Félix Fénéon: Aesthete & Anarchist in Fin-de-Siècle Paris, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1988, 211.

18John Rewald, Post-Impressionism: From Van Gogh to Gauguin, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1956, 426.

19Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp [1967], trans. Ron Padgett, London: Thames and Hudson, 1971, 22.

20See the brief account of the study of Seurat by artists of that generation given by Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Cubism and Abstract Art, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1936, 22.

21Guillaume Apollinaire, ‘The Art World’ [1910], Apollinaire on Art: Essays and Reviews 1902–1918 [1960], ed. Leroy C. Breunig, trans. Susan Suleiman, Boston, Mass: MFA, 2001, 100–5, 101.

22Guillaume Apollinaire, ‘From Eugène Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism’ (book review) [1911], Apollinaire on Art, 176–7, 176.

23Guillaume Apollinaire, ‘An Opening’ [1911], Apollinaire on Art, 188.

24Guillaume Apollinaire, ‘New Trends and Artistic Personalities’ [1912], Apollinaire on Art, 217–20, 219. See, for instance, his extensive quotation of Robert Delaunay on Seurat’s importance: Guillaume Apollinaire, ‘Reality, Pure Painting’ [1912], Apollinaire on Art, 262–5.

25Guillaume Apollinaire, ‘The Salon des Artistes Français’, [1914], Apollinaire on Art, 367–70, 369.

26Guillaume Apollinaire, ‘Seurat’s Drawings’ [1914], Apollinaire on Art, 379–80, 380.

27Kenneth E. Silver, Esprit de Corps: The Art of the Parisian Avant-Garde and the First World War, 1914–1925, Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989, 337.

28Breton, Conversations, 246. Also see the remarks made a few years after Breton, reporting the ‘laughing crowd’ that had assembled around the Grande Jatte at the eighth and last Impressionist exhibition in 1886, and the ‘incredible abuse’ heaped on Seurat’s innovations by press and public alike, given by Rewald, Post-Impressionism, 90, 97.

29André Salmon, ‘Georges Seurat’, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, vol. 37, no. 210, September 1920, 115–17 and 120–2, 116.

30Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp: A Biography, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1996, 218; Metropolitan Museum of Art, Georges Seurat, 363.

31‘Seurat est inconnu du grand public’, Florent Fels, ‘Seurat entre au Louvre’, Nouvelles littéraires, 22 November 1924, 3. Apparently, on his first trip to Paris in 1924 ten years before he joined the Surrealists, Hans Bellmer ‘concentrated his attention on the works of Seurat’, which barely affected his own later paintings and drawings but at least gave him a last sighting of several of those unwanted works before they were shipped out of France: Peter Webb with Robert Short, Hans Bellmer, London, Melbourne, New York: Quartet, 1985, 21.

32Bazin, ‘Seurat est le Vinci français’, 14.

33Halperin, Félix Fénéon, 385.

34Polizzotti, Revolution of the Mind, 18. More work should be done on Fénéon as potentially an intellectual mentor for Breton and Surrealism, especially since Breton compared his own early art criticism to Fénéon’s prescient appreciation of Seurat and Paul Valéry’s of Renoir when he wrote in later life of the importance of ‘l’oeil de la jeunesse’, André Breton, ‘“C’est à vous de parler, jeune voyant des choses”’ [1952], Perspective cavalière, Paris: Gallimard, 1970, 13–20, 14. A renowned anarchist in spite of his self-effacement, known to Alfred Jarry and Apollinaire, publisher of Arthur Rimbaud and responsible in 1890 for ‘the first generally circulated edition’ of Les Chants de Maldoror (1869) by the Comte de Lautréamont, Fénéon could not have failed to make a mark on Breton who with Louis Aragon in January 1925 made a note of his address (appropriately, it was 15 rue Eugène Carrière at the time) in the collective notebook of the Bureau de recherches surréalistes to ensure he was added to the ‘liste de services de la revue’ and years later wrote warmly to Jean Paulhan that he ‘got to know [Fénéon], was amazed by him, admired and loved him’ on receiving a copy of Paulhan’s edition of the writings of Fénéon in 1949: quoted in Halperin, Félix Fénéon, 172, 11; Paule Thévenin (ed.), Bureau de recherches surréalistes: cahier de la permanence, octobre 1924-avril 1925, Paris: Gallimard, 1988, 79. As late as 1951, Breton was privileging Fénéon’s authoritative scholarship on Rimbaud: André Breton, ‘Foreword to the Germain Nouveau Exhibition’ [1951], Free Rein [1952], trans Michel Parmentier and Jacqueline d’Amboise, Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1995, 241–3, 241; also see André Breton, ‘Caught in the Act’ [1949], Free Rein, 125–69, 130–1. In addition to Halperin, see the two articles by John Rewald, ‘Félix Fénéon (1)’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, vol. 32, July–December 1947, 45–62 and ‘Félix Fénéon (2)’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, vol. 33, January–June 1948, 107–26.

35See Breton, Conversations, 76. Breton had urged Doucet to purchase work by Seurat in 1923: see Breton, Oeuvres complètes, vol. 3, 1232. Breton had known Duchamp for a few years by then; alongside Duchamp’s friendship with Quinn’s agent Roché, this helps explain the letter Duchamp sent on 22 December 1923 to Doucet who collected and commissioned his work (for which we do not have Doucet’s letter in which a request for information about Seurat must have been made) where he expressed some admiration for Seurat’s painting, especially Chahut, ‘which, in my view, is his best’, and contempt for Paul Signac and Lucie Cousturier ‘his vile imitators/wigmakers’, alongside ignorance as to the whereabouts of his paintings (this is odd, since he must have known through Roché or through his acquaintance with Quinn that the collector had owned Circus since January that year), which must have been the substance of Doucet’s inquiry: Marcel Duchamp, Affectt Marcel._ The Selected Correspondence of Marcel Duchamp, eds Francis M. Naumann and Hector Obalk, trans. Jill Taylor, London: Thames and Hudson, 2000, 139. For Duchamp’s activities in the art market following Quinn’s death, see Tomkins, Duchamp, 270–4.

36Fry, Transformations, 195.

37Breton, Manifestoes, 9.

38See André Breton, ‘Surrealism and Painting’ [1925–8], Surrealism and Painting [1965], trans. Simon Watson Taylor, New York: Harper & Row, 1972, 1–48, 24 (translation modified); ‘ce chromo dont Seurat semble s’être si moqueusement, si littéralement inspiré pour peindre Le Cirque’, André Breton, ‘Le Surréalisme et la peinture’, La Révolution surréaliste, no. 9/10, 1 October 1927, 36–43, 38. In the full passage, Breton writes ‘pinned on the wall of Picasso’s studio, the litho which Seurat used …’, Breton, Surrealism and Painting, 24 (translation modified). Breton was referring to Seurat’s admiration for the posters of Jules Chéret; the inspiration he drew from them was widely reported from as early as 1889 and the comparisons were commonplace: see Robert L. Herbert, ‘Seurat and Jules Chéret’ [1958], Norma Broude (ed.), Seurat in Perspective, Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc., 1978, 111–15; Thomson, Seurat, 204, 207, 212–21. For an objection to Herbert’s cuddly Chéret, see Jonathan Crary, Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle, and Modern Culture, Cambridge, Mass. and London: MIT, 1999, 269 n. 273. Picasso was a step ahead of other Cubists into Seurat’s own sources: as recorded by André Salmon in 1920 about his contemporaries: ‘the first Cubist studios were hung with photographs of works by Ingres and Seurat, notably the Chahut, one of the great icons of the new devotion’, Salmon, ‘Georges Seurat’, 115; and as also witnessed a few years later by Florent Fels around the time Breton was writing: ‘une reproduction de son oeuvre Le Cirque qui entre au Louvre, est épinglée au mur des ateliers des peintres du monde entier’, Fels, ‘Seurat entre au Louvre’, 3. Reproductions of both Chahut and Circus appeared ‘entre deux bois nègres’ in the studios of young artists around 1910 (which might confirm the importance of the 1908–9 Bernheim-Jeune exhibition) according to Claude Roger-Marx, Seurat, Paris: Les Éditions G. Crès & Co., 1931, 8.

39Breton, Surrealism and Painting, 24.

40Alfred H. Barr, Jr., The Museum of Modern Art First Loan Exhibition, New York, November 1929: Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, van Gogh, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1929, 26.

41Silver, Esprit de Corps, 336.

42Salmon quoted from 1925 in Christopher Green, Cubism and its Enemies: Modern Movements and Reaction in French Art, 1916–1928, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1987, 188, 59.

43‘l’esprit constructif est aussi nécessaire pour créer un tableau ou un poème que pour bâtir un pont’, ‘L’Esprit nouveau’, L’Esprit nouveau, no. 1, 1920, 3–4, 3.

44Roger Bissière, ‘Notes sur l’art de Seurat’, L’Esprit nouveau, no. 1, 1920, 13–28.

45Lucie Cousturier, Seurat [1921], Paris: Les Éditions Georges Crès & Co., 1926, 18. Comparison of Seurat with both Ingres and Puvis had been commonplace among his acquaintances; for the ‘classicism’ of his work as understood in the 1930s, see Robert Rey, La Renaissance du sentiment classique: Degas, Renoir, Gauguin, Cézanne, Seurat, Paris: Beaux-Arts, 1931, 94–137.

46‘les vieux géomètres grecs’, ‘le sec de la grande tradition française’, ‘bon sens’, Amédée Ozenfant, ‘Seurat’, Cahiers d’Art, no. 7, September 1926, 172. Ozenfant had sought alignment for Cubism and, implicitly, his new aesthetic, with Ingres, Cézanne, Seurat and Henri Matisse as early as 1916: Amédée Ozenfant, ‘Notes on Cubism’ [1916], Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (eds), Art in Theory, 1900–1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, Oxford and Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1992, 223–5, 224; and explicitly so later by returning to the same artists and reproducing alongside Ingres’ work Seurat’s Young Woman Powdering Herself and several of the other later masterpieces with Cézanne’s five figure Card Players (1890–2) in Amédée Ozenfant and Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, La Peinture modern, Paris: Les Éditions G. Crès & Co., 1925 (Chahut adorns the book jacket in a kind of photomontage, supposedly illustrating the relationship between form and colour, which had been used originally in the first Seurat-heavy number of L’Esprit nouveau).

47‘style classique, d’un sentiment moderne’, Waldemar George, Seurat, Paris: Librairie de France, 1928, n.p.

48Silver, Esprit de Corps, 337.

49Silver, Esprit de Corps, 337.

50I refer to the well-known remark in the letter from Camille Pissarro to Signac made at a low point in their relations with the ambitious younger artist in 1888: ‘Seurat est de l’École des Beaux-Arts, il en est impregné … Prenons donc garde, là est le danger’, quoted (with ellipsis) in John Rewald, Georges Seurat, Paris: Éditions Albin Michel, 1948, 115.

51Breton, Manifestoes, 9, 10.

52Breton, Manifestoes, 16.

53Salvador Dalí, ‘Abjection et Misère de l’Abstraction-Création’, La Conquête de l’irrationnel, Paris: Éditions Surréalistes, 1935, 19–20.

54Roger Fry, ‘Seurat’s La Parade’, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, vol. 55, no. 321, December 1929, 289–91 and 293, 290.

55Daniel Catton Rich, Seurat and the Evolution of La Grande Jatte, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1935, 27, 29. Also see Robert J. Goldwater, ‘Some Aspects of the Development of Seurat’s Style’, The Art Bulletin, vol. 23, no. 2, June 1941, 117–30; and Lionello Venturi, ‘Piero della Francesca-Seurat-Gris’ [1953], Broude (ed.), Seurat in Perspective, 108–10.

56Hélion’s biographical entry in the book of the exhibition reads ‘[l]ives in Paris’, though he was in the process of moving to New York at that time: Barr, Cubism and Abstract Art, 211.