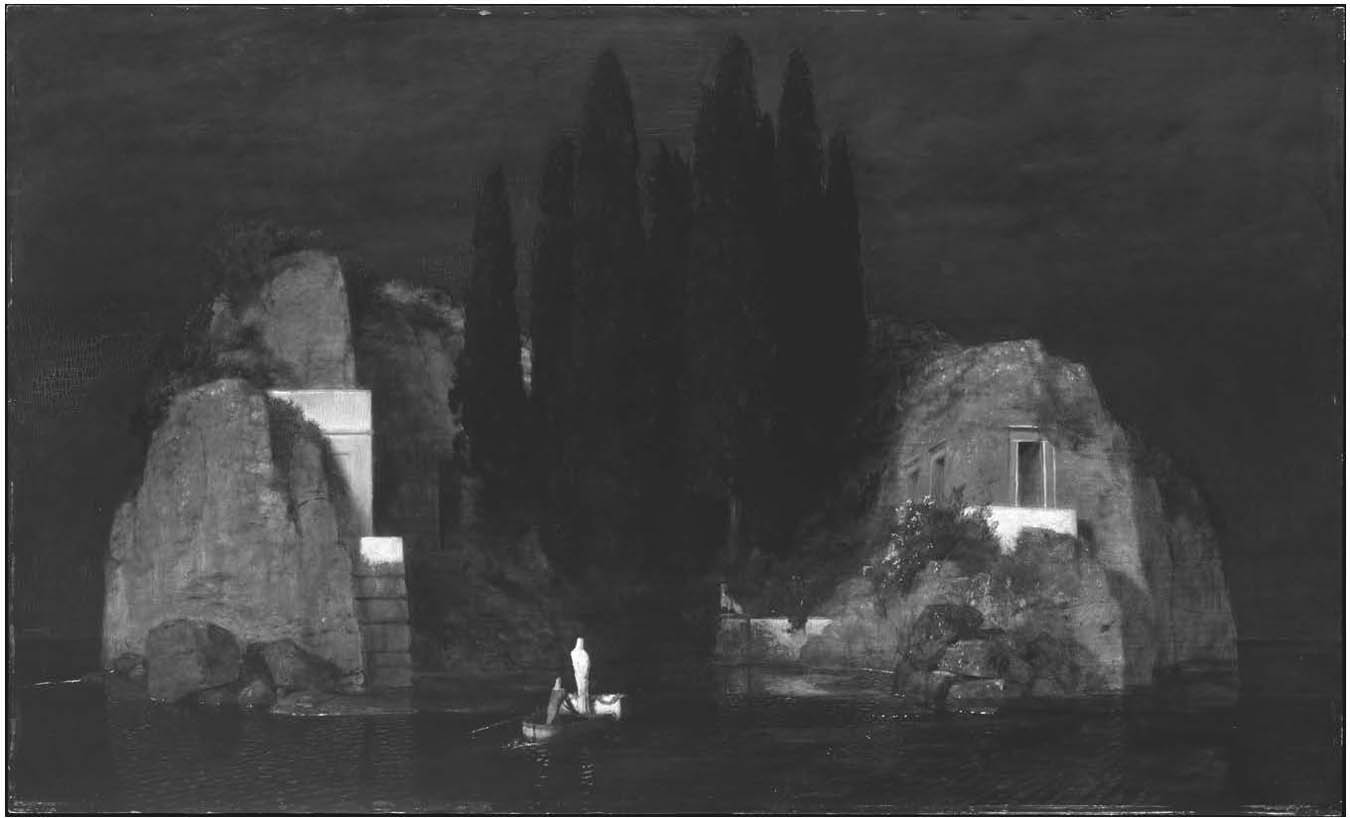

Readers of this book may well be familiar with the sections on artist ‘precursors’ that are found in the many histories, dictionaries, encyclopaedias and beginners’ guides devoted to Surrealism and its art. In those surveys, certain mid- and late nineteenth-century artists, particularly Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon as well as a few other regulars such as Arnold Böcklin (figures I.1 and I.2), Alfred Kubin, and even Fernand Khnopff, Edvard Munch, Félix Vallotton and J. J. Grandville, invariably and justifiably come in for comparison with Surrealist artists on formal, stylistic, thematic or iconographic grounds. Discussion of these commonalities is valuable and informative about both Surrealism and Symbolism and much more could be made of the suggestive resemblances between these two broad bodies of work and the fragments of text written within and about Surrealism that have been devoted to such artists and others who were earlier recognized by Symbolist writers.1

Figure I.1 Arnold Böcklin, The Isle of the Dead (1890). Oil on wood, 73.7 × 121.9 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art New York. www.metmuseum.org.

However, the attention given in the pages that follow to the painters that came to prominence in the late nineteenth century is extended only incidentally to those artists, to Symbolist painters generally, to Nabis such as Charles Filiger and Paul Sérusier, and to one-offs like Henri Rousseau, an artist who held a particular appeal for the Surrealists. My book collects and analyses, instead, the Surrealist commentary on the painters who became the canonical figures of early French modernism. This is an approach to the period that remains entirely novel at the moment of writing. Combining historiography and Surrealist theory to both review and extend the readings of that art by Surrealist writers and artists, this book submits such interpretation as an alternative to the treatments by ‘old’ and ‘new’ art histories, broadly meaning ‘formalist-modernist’, on the one hand, and the more contextual, political and theoretical approaches that enhanced the discipline from the late 1960s, on the other. The Surrealist writings revived and expanded upon here were and still are meant to compete with the former and have been suppressed by both. If they have been marginal, overlooked, ignored or derided, they were also belated, occasional, minor and ambivalent. In bringing them together and drawing out their ramifications and repercussions, I indicate significant gaps in the art historical record. My goal is to identify a Surrealist position on the foundational canon of late nineteenth-century French painting, a canon that emerged in modernist art criticism, art history and curatorship at the beginning of the twentieth century and was consolidated from then up to the mid-1950s.2 Across that era, we can track the fervent arc of historical Parisian Surrealism itself and it therefore acts as the period frame for the ‘appraisal’ of my title.

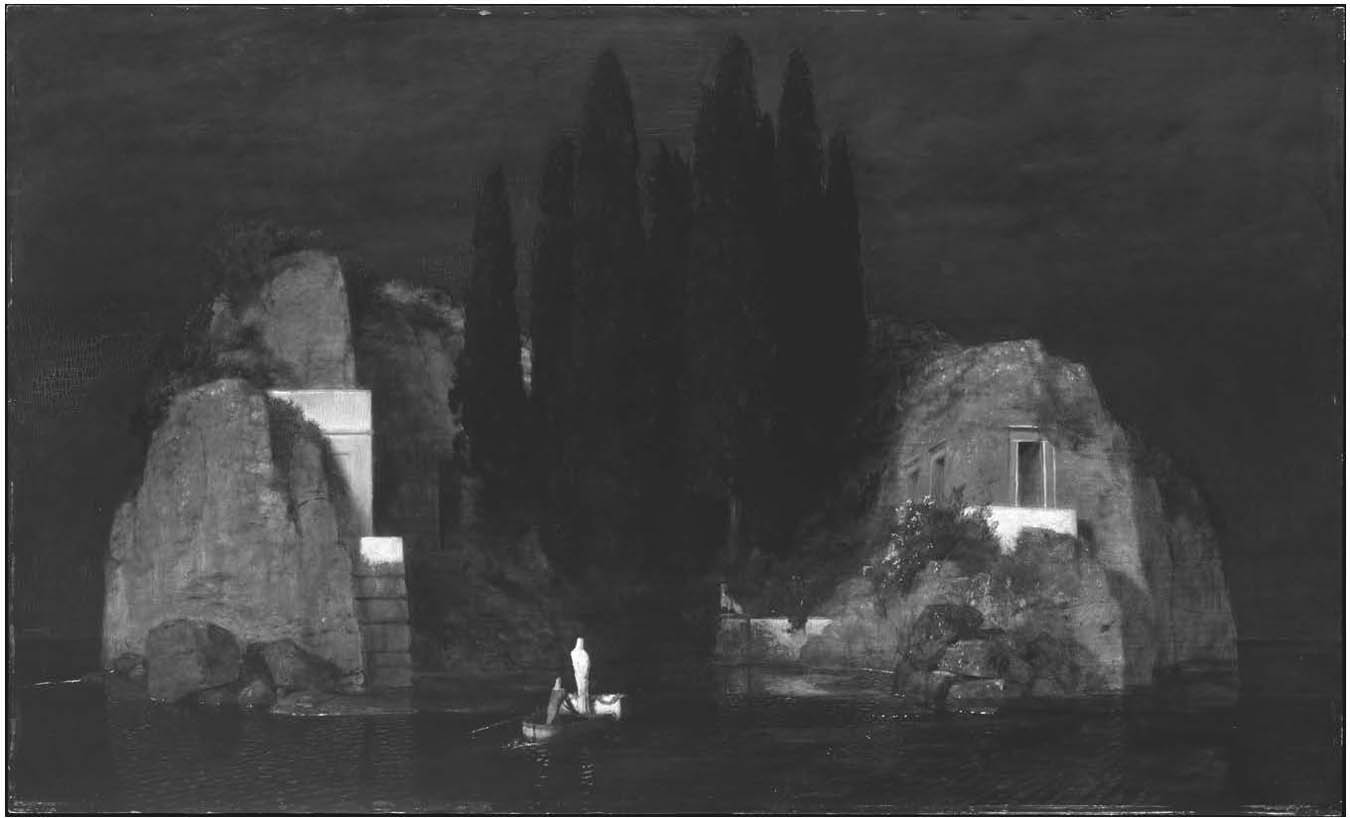

Figure I.2 Salvador Dalí, The Birth of Liquid Desires (1932). Oil and collage on canvas, 96.1 × 112.3 cm. The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice. © Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venezia (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York). © Salvador Dali, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, DACS 2018.

The idea of making a swerve from the customary artists of the late nineteenth century who are seen to predate Surrealist painting, such as Moreau, Redon and Rousseau, had a strong, counter-intuitive appeal for me. But I also found while researching and writing this book that an alternatively finessed canon to the modernist one was developed in patches in Surrealism. I believe that is worth collating and unifying for the study of modernism and for academic art history and will offer a new contribution to scholarship on Surrealism. I choose my words carefully here because Surrealism did not tender an entirely dissimilar range of artists to those privileged in modernist art criticism and art history, as I will show; rather, it filtered those who had long and not-so-long ago achieved eminence in the 1920s such as Paul Cézanne and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, those who had not (at the time) such as Georges Seurat and those well on their way to doing so such as Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh, through its own theoretical or thematic proclivities by which their reputations within the movement stood or fell. This qualitative reassessment by Surrealism is more than has been managed by contemporary art history, which tends to uphold the same canon in spite of its abjuration of the very formalist and modernist modes of writing that were instrumental in creating it.3 In this sense, my book sometimes proposes Surrealist writings on those artists as alternatives to the ones of academic art history.

These Surrealist tendencies against which earlier artists were judged did not merely differ from the accents placed by modernists, they represented an entirely different system of values for interpreting and evaluating art. There is much complexity and nuance on both sides and their edges even touch at certain points. However, a way of broaching this divergence in a manner easy to understand is to say that the well-known prominence given in the first two-thirds of the twentieth century by formalist and modernist critics and writers, art historians and curators to the formal, aesthetic and stylistic elements of works of art (qualitative judgements on colour, line, shading, volume, space, composition and other perceptual material-based aspects of art) at the expense of consideration of recognizable, representational content was almost entirely reversed by Surrealism’s devotion from its beginnings in the early 1920s to a poetics of art, and increasingly from the late 1930s to how that poetics incubated eroticism, occultism and magic.4 For this reason, I chose a term from an 1889 letter from van Gogh that I quote from in this introduction and will return to a few times in my book, meant by that artist to affirm his practice as a mode of realism and not fantasy, giving me a way of thinking about this alternative Surrealist reception and also providing me with my accidentally surrealist and perhaps Magrittean title Enchanted Ground.5

Although I will have something to say about the (no doubt unexpected) ‘surrealism’ of the pioneers of modernist painting – Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet and the early Cézanne – I take the art that followed in France immediately after Impressionism, repudiating that movement to a greater or lesser extent, as that which the Surrealists came to see in terms of their own ends, as the most relevant of the second half of the nineteenth century. What form did that complaint against Impressionism take and how was it processed in Surrealism?

By the early 1890s, Impressionism was being challenged by alternative forms of modern art that saw painting as the vehicle for other kinds of knowledge, and by Symbolist supporters such as writer-critics Félix Fénéon and Gustave Kahn, anxious to dissociate the generation of Neo-impressionists from it.6 Of the cohort of painters critical of the Paris Salon who came to prominence after the Impressionists, Gauguin was the one who came to reject their attitudes most violently in the wake of Symbolism. This was carried out with an ideological fervour in the widely quoted passage with which ‘the Surrealists would have agreed without hesitation’, according to José Pierre7:

They studied color, and color alone, as a decorative effect, but they did so without freedom, remaining bound by the shackles of verisimilitude. For them there is no such thing as a landscape that has been dreamed, created from nothing. They looked, and they saw, harmoniously, but without any goal: they did not build their edifice on any sturdy foundation of reasoning as to why feelings are perceived through color.

They focused their efforts around the eye, not in the mysterious center of thought, and from there they slipped into scientific reasons.… Intellect and sweet mystery were neither the pretext nor the conclusions; what they painted was the nightingale’s song. … Dazzled by their first triumph, their vanity made them believe it was the be-all and the end-all. It is they who will be the official painters of tomorrow, far more dangerous than yesterday’s.8

Although Gauguin recognized some of the initial achievements of the Impressionists, especially those of Claude Monet, his conclusions were unsparing: ‘[w]hen they talk about their art, what exactly are they talking about? An entirely superficial art, nothing but affectation and materialism; the intellect has no place in it.’9

These lines would eventually appear in Diverses Choses written in 1896–8 around the time Gauguin painted Te Rerioa (The Dream), Nevermore and Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (which the Surrealists would come to revere).10 It has been argued that they are implicitly evoked in André Breton’s attempt as early as 1923 in the essay ‘Distance’ to prioritize the art of Gauguin and Seurat over that of Cézanne at the origins of twentieth-century art.11 In any case, they make an evidently neat fit with Breton’s founding statement, first uttered in 1925, about the demand made by Surrealism on the visual arts, which forms the most important, theoretical opening part of Surrealism and Painting (1928). Appealing there for recourse to ‘a purely internal model’, at a time when, he said, philosophy and science were making ‘the external world … increasingly suspect’, Breton asserted: ‘to make the magic power of figuration with which certain people are endowed serve the purpose of preserving and reinforcing what would exist without them anyway, is to make wretched use of that power’.12 No wonder Breton would quote Gauguin’s ‘mysterious centre of thought’ in years to come in support of this opinion.

Even at this early stage in Breton’s thinking about the visual arts, then, for him as for Gauguin, ‘magic’ in art was meant to bring forth the invisible not represent the visible. In spite of the period and cultural contexts (and the different vocations of poet and painter) that separated them, it was a shared position that articulates starkly their remoteness not just from Impressionism, but also from some artists who came after the Impressionists and equally painted from nature. This brings me to the famous letter by van Gogh the realist who wrote to Émile Bernard in November 1889 using the term ‘abstraction’ to denote and critically defame the limitative intrusion of the imagination in painting along these paradoxical lines: ‘[w]hen Gauguin was in Arles, I once or twice allowed myself to be led into abstraction, as you know … and at that time abstraction seemed an attractive route to me. But that’s enchanted ground [terrain enchanté], – my good fellow – and one soon finds oneself up against a wall.’13 Van Gogh’s judgement on the recourse to imagination in painting as alluring but inevitably constrained throws into relief the shared ground of Breton and Gauguin. It is the firm but fantastic terrain that underlies the polemic of the former in the Manifesto of Surrealism (1924) against the contraction of the imagination from childhood on by the social utilitarianism entailed by capitalism, and the one that bears Gauguin’s abrupt shelving of the ‘exactitude’ insisted upon by realism in an earlier letter to Bernard of November 1888.14

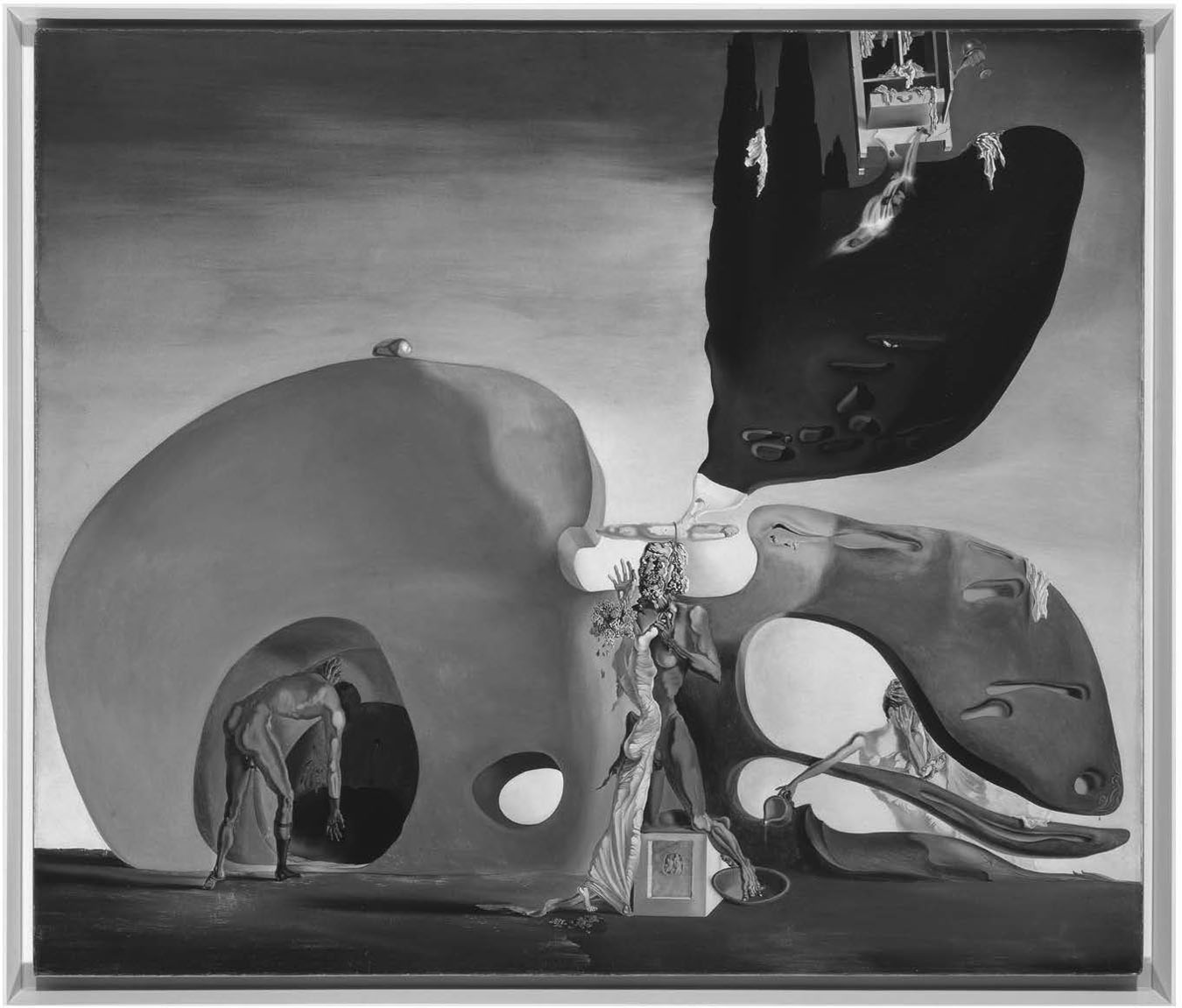

Yet in spite of a common outlook held between Breton and Gauguin on the task of painting, it would be a long time before Gauguin received any concerted attention in Surrealism. At first, Breton saw the late nineteenth-century precursors of the movement as poets not painters: the Comte de Lautréamont (Isidore Ducasse), Arthur Rimbaud and Stéphane Mallarmé.15 Then in his subsequent writing of the 1920s and for some time after, it was the Cubist-era Pablo Picasso who acted as his chronological point of departure for the important and up-and-coming art of that decade. At that point, already in conflict with the emerging formalism, art was seen by Breton to be less about experiments with form than with an ‘inwardly’ directed examination that indicates a ‘future’ or beyond shared with poetry and even the ‘literature’ usually derided by the Surrealists:

We leave behind us the great grey beige ‘scaffoldings’ of 1912, the most perfect example of which is undoubtedly the fabulously elegant Man with a Clarinet [figure I.3, 1911–12], whose ‘parallel’ existence must remain a subject for endless meditation. … The Man with a Clarinet remains as a tangible proof of our unwavering proposition that the mind talks stubbornly to us of a future continent, and that everyone has the power to accompany an ever more beautiful Alice in Wonderland.16

Breton would continue to hold Cubism and especially the Man with a Clarinet in very high esteem up to his last major word on art in L’Art magique (1957). By then, however, it was Gauguin’s imagining of an alternative to plain reality in pursuit of a personal myth that would draw the greater attention of Surrealism, even though mythic themes took on an entirely different appearance in Gauguin’s art to Picasso’s and even the Surrealists’.

For that reason, Breton quoted from the closing part of Gauguin’s refutation of Impressionist opticality – about superficiality, affectation and materialism – in one of the lectures he gave on his pedagogical visit to Port-au-Prince in Haiti in 1945–6, taking it as a general denunciation of the ‘occidental’ art of Gauguin’s day.17 Earlier in that lecture, which was given over entirely to the art of the second half of the nineteenth century but remained unpublished in his lifetime (and will be discussed at length in my second and, especially, third chapters), Breton made his own most extensive comments to date on Impressionism. Crediting Eugène Delacroix with the invention of the modern spirit in painting as that had culminated in Surrealism, while acclaiming Courbet as the inventor of an oneiric atmosphere in painting that would be inherited by the equally mediumistic though stylistically entirely dissimilar canvases of Giorgio de Chirico, Breton turned briefly and with reservations towards the Monet–Renoir wing of Impressionism:

Figure I.3 Pablo Picasso, Man with a Clarinet (1911–12). Oil on canvas, 106 × 69 cm. Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. © Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza/Scala, Florence. © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2018.

Impressionism, as a movement in reaction against those that had preceded it, repudiated, in fact, the Romantic imagination and all that which painters named with ill-will literature. Indifferent to philosophy and poetry, the Impressionist painters claim to paint only what they see and as they see it, focussing above all on water, the sky and mists, or in other words on everything that time makes and unmakes indefinitely. The unsolicited find [trouvaille], fruit of simple chance as almost always, which gave flight to Impressionism, seems to have been the initially vague and completely involuntary observation of the reflection of a landscape on the water of a river.18

This was a well-worn take on Impressionism that had its source in Symbolist circles in the early 1890s, but was redeemed at least a little in Breton’s rendering by his refusal to lump every non-Symbolist from Courbet and Manet through to Seurat with Impressionist ‘materialism’ or ‘positivism’. Beyond this, however, he gave his attentive Haitian audience hungry for culture only an abbreviated introduction to the Impressionists as artists preoccupied with temporality and light and too tied to the surfaces of objects to create anything more decisive than a ‘visual revolution’.19

No doubt Breton had always thought of Impressionism in this way. But it is significant that he stated only in the mid-1940s that it was a kind of aberration in the recent history of art, in reaction to that which had come before it and in poor contrast especially to what came after it, an opinion that had been consolidated through conversations with Marcel Duchamp in New York during the Second World War.20 In a similar fashion, and not coincidentally, Clement Greenberg had pronounced Magrittean and Dalinian ‘academic’ Surrealism a deviation from the historical logic of avant-garde painting a little over a year earlier.21 Breton and Greenberg would continue to devise competing lineages of the most important modern art during the Cold War, through the 1950s driven by a mutual detestation of socialist realism, and into the 1960s. In the Surrealist account, Impressionist opticality made no sense to the validation of a metaphorical and increasingly magical content in art, while in the modernist narrative, much Surrealist art was excused from a canon formed in the wake of Impressionist truth-to-materials as ‘academic’, ‘kitsch’ or, yes, ‘literary’.

Breton would protest again the ‘literary’ label given by some to any art that was neither realist nor merely for visual delectation on the occasion of Dessins Symbolistes, the 1958 exhibition he curated with the collector and gallery owner Mira Jacob at the Bateau-Lavoir gallery, which had opened three years earlier specializing in works on paper from the late nineteenth century onwards.22 After a dip in its critical fortunes in the 1920s and 1930s, Monet’s painting had been thoroughly revived by then, largely thanks to the success of abstract expressionism. This trend had been helped along by the recent opinion given prominently by the former Surrealist André Masson in which Monet was viewed as a revolutionary who created a ‘[n]ew way to see, to feel and to love nature’, with an illustrious phrase from Breton’s Manifesto cheekily dropped in to make the case: ‘here the imagination regains its rights’.23 Breton used his essay in the catalogue of Dessins Symbolistes to try to tip the historical record back in favour of Symbolism and Surrealism. However, he must have had the modernist defence of US abstraction in mind as much as Impressionism when he complained that Symbolist art ‘appeared for a long time to have been swept away entirely by the tide of Impressionism’, quoting again for support from the conclusion of Gauguin’s dismissive remarks about that movement.24 In that text, Breton also roped in the equally disparaging observations made by the chronicler of Gauguin and Symbolism, Charles Chassé, and the one by Redon whose quip about not embarking on the Impressionist boat, ‘because I found the ceiling too low’, had been repeatedly cited by Sérusier to Chassé.25 Breton had never had much time for the Fauves who had failed to live up to the example set by Moreau, the one-time teacher of several of them, referred to in Dessins Symbolistes as the ‘great visionary and magician’.26 More unexpectedly, his old confidence in the capacity of Cubism to transport its audience to another world had gone by that time and it had been brought equally low as Impressionism in his estimation (caused partly by Picasso’s all-too-real conversion in this world to Soviet communism). Breton now saw both Fauvism and Cubism as mere ‘off-shoots’ of Impressionism, ‘limit[ing] themselves strictly to an external view and insist[ing] on wasting our time with trivial objects physically within reach’.27

When considered alongside the title of Breton’s catalogue essay, ‘Préface-Manifeste’, the 1958 exhibition Dessins Symbolistes points to a wish to counter both the modernist canon and the formalist means by which it was validated by the dominant modernist criticism and writing. The continued vigour of the latter could be viewed in that very year where the supposed proto-modernism of Seurat was restated by Robert L. Herbert, at the time of the slightly early ‘centenary’ exhibition held for the artist in Chicago, which ended on the day Dessins Symbolistes began.28 In conjunction with the attention they gave to Symbolist art, the Surrealists’ make-over of Gauguin had been underway for nearly a decade by then and the stronger case they made for the Surrealist Seurat for much longer in the face of the modernist account that had increasingly shaped the institutional narrative of modern art history. Breton would have become more aware of that orthodoxy while in New York during the Second World War. He could have witnessed since then the growing interest shown in, and bigger exhibitions given to the work of Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat and van Gogh by modernist critics, art historians and curators. Accordingly, he attempted to appropriate Gauguin and Seurat in Dessins Symbolistes, stating that ‘the whole exhibition hinges upon this deliberate juxtaposition of the work of these two masters’.29 In this way, he returned them to Symbolism and therefore to a history that was relevant to Surrealism even as Breton and the Surrealists modified the canon through their elimination of Cézanne and resistance to van Gogh.

Given this leaning, it is mildly ironic that the status of those four artists as the patriarchs of modern painting was achieved partly by writers dear to Breton, long before the advent of formalist modernism, as he knew. In the article he wrote for the weekly cultural newspaper Arts in November 1951, ‘Alfred Jarry as Precursor and Initiator’, which responded to the recent publication of the Oeuvres complètes of Jarry by surveying what was, till then, the little-known range of his writing, Breton gave prominence to the exceptional foresight of Jarry’s understanding of art, since he was the first to predict the largely post-Impressionist litany of Cézanne, Renoir, Manet, Gauguin, van Gogh and Rousseau in the 1890s.30 Much earlier and more important than this, it must have been through Guillaume Apollinaire by whom he was mentored as a poet from late 1915 to 1918 that Breton became comprehensively apprised of that emerging canon in his pre-Surrealist years for, remarkably, as early as 1907, Apollinaire’s hit-and-miss art criticism had lined up and isolated the four pioneering early modernists in a single sentence at a time when only Cézanne’s reputation was secure.31

By then, the modernist canon was already bound to an early variety of formalism, helped along by the writings of Maurice Denis on the Impressionists, Symbolists, Cézanne, Gauguin, van Gogh and others, fronted by the artist-theorist’s declaration of 1890, which became a sort of axiom: ‘Remember that a picture – before being a horse in wartime, a nude or some anecdote or other – is essentially a plane surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order.’32 Breton’s interest in Denis as an artist would remain minor due mainly to his ‘eventual surrender to religious stereotype’, as Breton put it; he would harbour a similar reservation about Bernard who also played a significant role in the standardization of the early modernist canon (and was powerfully present in the Dessins Symbolistes project through the twenty-four-run limited edition of the catalogue, twelve of which each contained an original drawing by him).33 His opinion on Denis had remained firm in the face of the efforts of the critic Charles Estienne in the late 1940s to turn the famous quotation towards ends favourable to a Surrealist reading, by means of a triangulation of Denis’s ‘subjective conception’ and Wassily Kandinsky’s ‘inner need’ with Breton’s ‘purely internal model’.34 In the end, Denis’s writings received a wholly different emphasis to their nascent formalist one from the Surrealists, who seem to have overlooked the equal invitations to enchantment they offer. An example of this can be found in the conclusion of the same introduction to Théories 1890–1910 (1912), for instance, where Denis saved his formalism from mere materialism by speaking of great art from the ancients to the moderns as ‘the disguise of natural objects, with their vulgar sensations, as icons that are sacred, hermetic and commanding’.35 Instead of capitalizing on such remarks, the Surrealists gave prominence to Denis’s commentary on the spiritual qualities of Gauguin’s teaching and leadership, as I detail in the fifth chapter of this book.

Perhaps the key early event in the history of the creation of the genetic modernist canon was the curatorial primacy given Cézanne, Gauguin and van Gogh in the exhibition of 1910 Manet and the Post-Impressionists, organized by Roger Fry and held at the Grafton Galleries in London. That is because the event drew the three artists together under a theory that placed the accent on the formal concerns of their art through a standardized, bureaucratic language. This lay in the ‘simplification of planes’, ‘design’, ‘architectural effect’, ‘geometrical simplicity’, ‘fundamental laws of abstract form’, ‘rhythm’ and ‘abstract harmony of line’ (even as that other modernist preoccupation with what Fry called the ‘principle of expression’ was shared by the Surrealists who sought the source of it in the unconscious).36 It was a means of understanding the importance of Cézanne, Gauguin and van Gogh that Fry would extend to Seurat in the 1920s.

The endeavours of the essential artists privileged by Fry and Bell were buried deep among the 1,300 works shown at the massive Armory Show held in New York in 1913: Cézanne was represented by sixteen, Gauguin by fourteen (‘one’ of which was a set of lithographs), van Gogh by eighteen and Seurat by a paltry two. Their appearance came as a surprise to Americans still hooked on Impressionism, according to Meyer Schapiro, who wrote in the early 1950s once their pre-eminence was secure: ‘we had ignored the art of van Gogh, Gauguin, Seurat, and the later Cézanne’.37 That situation soon changed, aided by the fundamental approach taken by Fry and Bell into the 1920s and beyond, which undermined Impressionist ‘objectivity’, a strategy plausibly and ironically linked by Mary Tompkins Lewis to the rise of Surrealism.38 It was confirmed, consolidated and amplified in the English-speaking world in 1929 by the earliest activities of the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York, which opened its curatorial programme with an exhibition of those artists that would be the highest attended show in the first ten years of the museum. Through that event, a recently triumphant German Expressionism rather than a yet-to-be-validated Surrealism was viewed by Alfred H. Barr, Jr. as the historical outcome of the work of Gauguin and van Gogh. This was argued in a hyperbolic catalogue essay that had not yet fully succumbed to formalism but did bear evidence of Barr’s admiration for the way of writing about art popularized by Fry (whom Barr had met two years earlier).39

The remarkable success of that exhibition of 1929 gives some credence to Isabelle Cahn’s assertion that Cézanne, Gauguin and van Gogh had been the key figures for modernist writers since the 1930s.40 The concerted revival of classicism in modern art in Europe around the beginning of the First World War had not checked this; that style and ideology demanded only that the inconvenient van Gogh should be replaced in the narrative by Seurat on certain occasions. The ‘classicism’ of Seurat, as it was recognized from the 1920s by conservative critics and writers such as Robert Rey, did nothing to prevent the beginnings of his surrealization in the same period, as I show in my third and fourth chapters.41

Following the relative hiatus in publishing and exhibiting caused by the Second World War, the canon was consolidated through the attention given those artists by American critics, collectors and curators. Initially, in a review of the Gauguin exhibition held at the Wildenstein Gallery in New York in April 1946, Greenberg suggested a decline in that artist’s repute in the preceding years.42 This could not have been much more than a wartime blip because the historical record shows a slow and steady escalation in the visibility of Gauguin’s paintings. This was about to accelerate, as I show in my fifth chapter, partly due to the efforts of Breton who returned to France from New York later in April that year at the end of his wartime stay in America soon after viewing the same Wildenstein exhibition.43 The reassessment was piloted in France by the 1949 ‘centenary’ exhibition Gauguin, held at the then Orangerie des Tuileries, at which time the curator and art historian René Huyghe had Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat and van Gogh down with Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec as the most important artists after Impressionism.44 By the 1950s, this hierarchy was so beyond dispute in Europe and America that Robert Goldwater could lead out his 1957 monograph on Gauguin with the apparently incontestable declaration that the artist was one of ‘[t]he four fathers of modern painting’.45 In a now-familiar teleology, he went on to assert that Cubism and abstraction in the twentieth century were the whole point of late nineteenth-century art: ‘[t]here is an intimate connection between Gauguin’s strong reaction against Impressionism and his subsequent influence. The analytic approach of Cézanne and Seurat bore its fruit in Cubism and geometric abstraction.’46

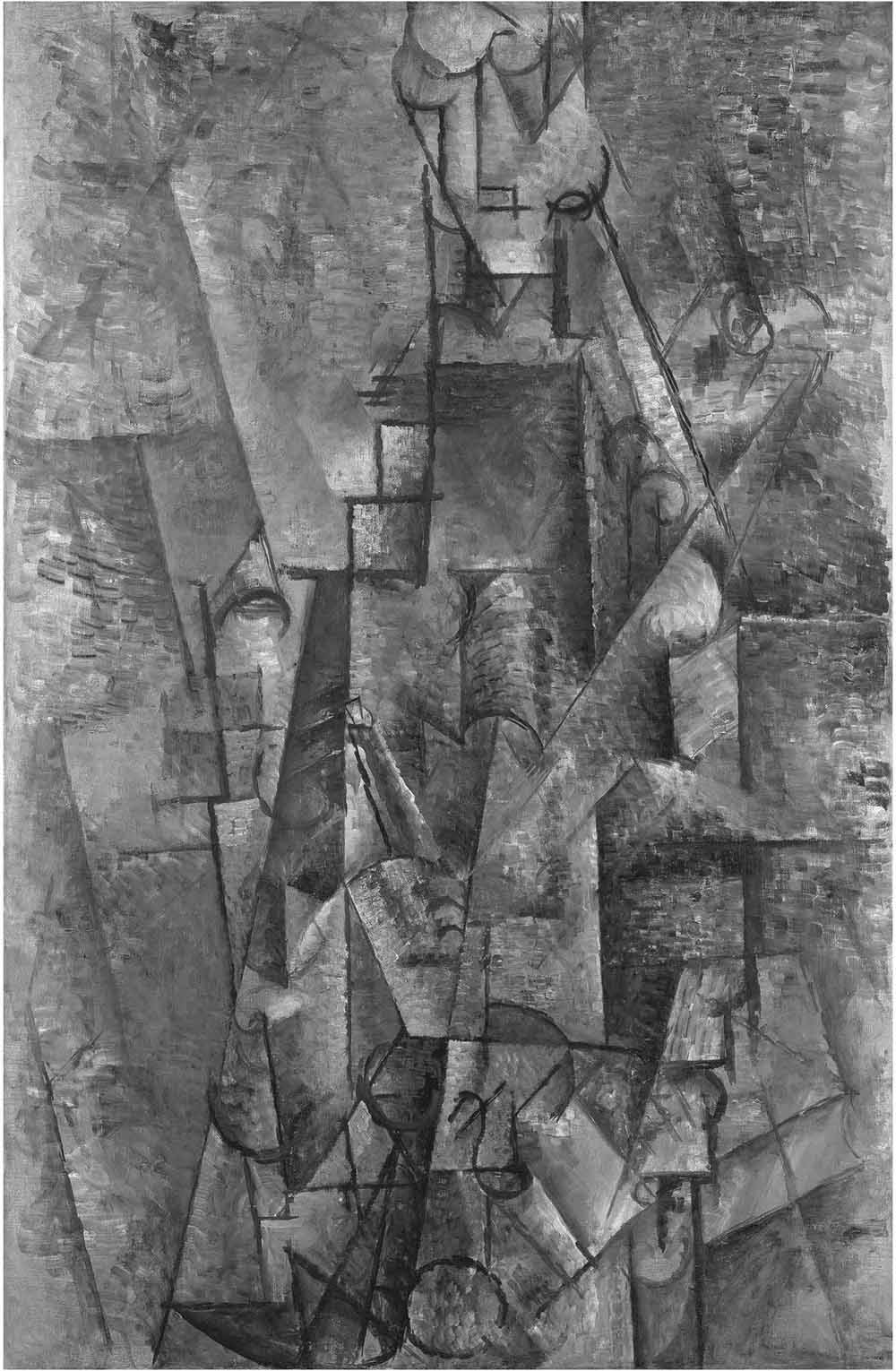

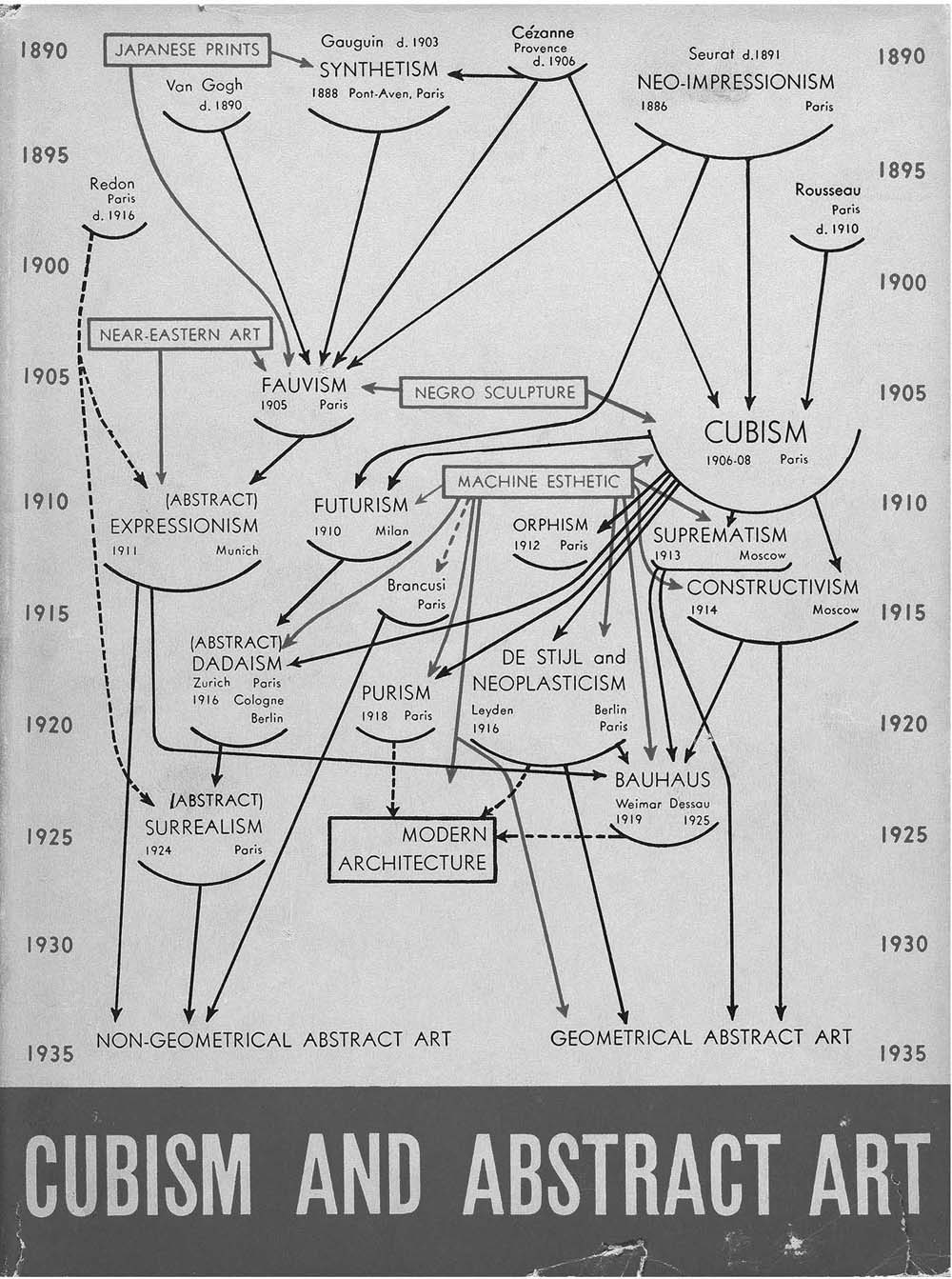

Barr ceased to be director of MOMA in 1943 but stayed on at the museum till 1968. In the period between, Goldwater, Greenberg, John Rewald and Herbert were chief among those art historians and critics in the US who helped seal through formalist means the reputations of Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat and van Gogh. Breton had plenty of dealings (most of them fractious) with Barr during the organization of the 1936–7 MOMA-organized travelling exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism so he must have known about formalism before the Second World War.47 This is especially the case since the museum’s modernist ideology was aggressively on display in the event that preceded it, Cubism and Abstract Art, for which Barr’s diagram (figure I.4), in which all of twentieth-century art tumbles mainly out of the achievements of the four artists from ‘1890’, provided Goldwater with his cue about their paternity. However, that bias was not evident in the Surrealism show or reflected in the booklet by Barr that went with it and was referred to only by contrast with the (unspecified) ‘fantastic’, ‘irrational’, ‘spontaneous’, ‘marvellous’, ‘enigmatic’ and ‘dreamlike’ content of Surrealist art in the pamphlet distributed as a guide at the exhibition.48

Figure I.4 Alfred Barr diagram for exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1936. © Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence.

Breton must have come into contact directly or through their writings with art historians or critics in New York during the war. He could earlier have met Goldwater who was in Paris in 1937–8 as a student researching what would become his best-known book Primitivism and Modern Painting (1938), containing a section on Dada and (mainly) Surrealism. In that period, Goldwater met his future wife Louise Bourgeois who had lived in the same building that housed Breton’s Galerie Gradiva for a little over a year from the beginning of 1937, so there were opportunities to meet.49 In New York Breton got to know very well personally the French-speaking Schapiro who was so close to Goldwater that the prefatory note in Primitivism and Modern Painting could state that he had ‘followed the work from its beginning’.50 Others available for discussion on trends in criticism and historiography at the time included artists, critics and writers in the vicinity of Surrealism such as Lionel Abel, David Hare, Gerome Kamrowski, Robert Motherwell and Harold Rosenberg, as well as the collector, writer on contemporary art and future dealer Sidney Janis. From these and other sources, Breton knew at first hand despite his limited English about the formalist justification of the modern canon.

As I already noted and will show in detail in this book, Surrealism had its own ideas about those artists, refusing to endorse the same canon. However, it should be conceded that Breton could be moved under certain circumstances, such as those created by Soviet cultural policy, to toe the line of modernist institutional convention. One example of his compliance can be found in this typically calculated roll call from the early 1950s given in a statement in Arts about ‘the concept of a living art, in the sense of a passionate quest for a new vital link between man and things’, as opposed to the deadness he thought to be innate to socialist realism:

All those who have some notion of what this art is about understand that what is at stake is a spiritual adventure that simply cannot be interrupted at any price. They know that it is along that royal road that are inscribed in modern times the names of [William] Blake, Delacroix, Géricault, [Henry] Fuseli, Courbet, Manet, Cézanne, Gauguin, van Gogh, Seurat and that it extends magnificently all the way to us.51

This ‘royal road’ (voie royale) (with Impressionism-shaped breach, but rare inclusion of Cézanne and van Gogh as stones upon it) bears in its terminology the prioritization that is always given in Surrealism of the ‘interiority’ of the subject as opposed to formal concerns.52 This had been sought in dreams before the war, which had been important to its painting and pivotal to the Surrealist object, while the route to the self would be signposted by the languages of esotericism in the postwar period. The Surrealist assessment of the canon instituted by modernism – unusually proffered without demurral in the names tacked onto the lineage in that declaration – has never been cogently given, with the exception, perhaps, of certain passages in Breton’s own L’Art magique, which was commissioned the year after those remarks appeared. That book can be viewed as Breton’s own fullest attempt to counter formalism, which by then was well and truly prevailing.

Such can be verified through Herbert’s apologetically stated avowal made while writing on Seurat in 1962 in a formalist manner only fringed by the barest contextualism, at the very moment modernist art and criticism were finally coming into question, that the twentieth century had been ‘dominated by formalistic considerations.… We delight in investigating the abstract components of art, and too often give a secondary place to the artist’s ties with the tangible world.’53 The elevation of Seurat’s reputation among critics from Fry’s late discovery of the artist, probably towards the end of the First World War or shortly thereafter, up to the moment Herbert was writing, was, of course, more down to the rise and rise of varieties of formalism than of the 1920s classicism that had initially bolstered it. This was carried out most blatantly in the numerous analyses of Seurat’s work using diagrams, schematic drawings and grids as though to distract from or obscure the actual content of the paintings. These ranged from the comparison of the ‘straight line organisation’ of A Sunday on La Grande Jatte – 1884 (1884–6) with its ‘curved line organisation’ by Daniel Catton Rich in the mid-1930s, through Germain Seligman’s investigation of Seurat’s drawings with bespoke linear illustrations in the mid-1940s and Henri Dorra’s grids at the end of the 1950s, up to Niels Luning Prak’s use of Gestalt figures in his consideration of the Grande Jatte and other paintings at the beginning of the 1970s.54

By the 1950s, the retrospective term ‘post-impressionism’, which had been introduced reluctantly by Fry in 1910 almost simultaneously with his announcement of the essential quality of the form of works of art and taken up in Britain and America and more rarely in France, was equally well established.55 Although Rewald also demonstrated hesitancy and caution when writing of it in 1956 as ‘not a very precise term’, he concluded that it is ‘certainly a very convenient one’ in the still useful though much maligned study Post-Impressionism: From Van Gogh to Gauguin in which the key artists are three of the four (minus Cézanne because of his slightly later prominence among artists and dealers).56 In spite of Rewald’s monumental effort, it was asserted by Alan Bowness in 1979 that ‘no serious comprehensive history of post-impressionism has been written, and perhaps none can be written because the unity of an artistic movement is quite simply lacking’, while Bowness himself made an attempt to begin a history of the term.57 Soon after those words appeared, Rewald and Bowness received a thorough going-over from Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock for being joint contrivers of the simplifying-by-chronologizing habits of modernist art history.58 I assess critically their important article at some length in the sixth chapter of this book then return to it in my last chapter under the shadow of a folk Surrealism I infer as shared by Breton and Gauguin.

My assessment through Surrealism of Pollock and Orton’s interpretation of Gauguin’s Brittany entails no retrieval of the old art history or the term ‘post-impressionism’, which was used only rarely by Breton and the other Surrealists.59 I have avoided exercising it here mainly because of its historical suggestion of some kind of agreement among artists (stylistic, methodical, critical, generally intentional or other) when that was only available here and there. However, I have kept to the key figures of the modernist canon it demarcates since the whole point of this book is to highlight and evaluate critical responses to those artist and contributions to their reputations from the perspective of the Surrealists. For them, art was meant to aspire to the condition of poetry. Increasingly, during and after the war, this was a poetry found less through dreams and the unconscious than by recourse to magic.

By these two terms ‘poetry’ and ‘magic’, I mean to refer initially to the responsibility heaped on metaphor in Surrealism, as determined unequivocally by Breton in ‘Surrealist Situation of the Object’ (1935):

The poet, whose role it is to express himself in a more and more highly evolved social state, must recapture the concrete vitality that logical habits of thought are about to cause him to lose. To this end he must dig the trench that separated poetry from prose even deeper; he has for that purpose one tool, and one tool only, capable of boring deeper and deeper, and that is the image, and among all type of images, metaphor.60

Along what path did poetry/metaphor meet magic in Surrealism? Odd, local events of action-at-a-distance that evaded contemporary rationalist causality had been identified and circulated in the 1920s among Surrealists as an effect of the unconscious, like the turbulent metaphorical imagery obtained by automatism (the best known can be found in Breton’s Nadja of 1928). These could already be situated in a framework of esoteric knowledge given by their contemporary reading of J. G. Frazer (whose vast repository The Golden Bough of 1890/1906–15 was translated into French in 1911–15) and Sigmund Freud’s Totem and Taboo (1913, French translation 1923, where Frazer is an important source), as well as Éliphas Lévi, Lucien Lévy-Bruhl and perhaps Marcel Mauss, who were also read by former friends and enemies of Surrealism.61

By 1930, Louis Aragon could write of the re-enchantment of the world brought about by the modern marvellous, of which collage was one of the chief exemplars, ‘recall[ing] more the procedures of magic than those of painting.’62 Aragon’s promotion of collage was meant to counter what it lamented as the ‘success of Cézannism’ for the visual arts and is saturated with references to magic and enchantment.63 It asserts that beginning with Duchamp and Francis Picabia, these ‘new magicians have reinvented incantation’, and collage itself had replaced painting by ‘restoring its true meaning to the ancient pictorial act’, leading the artist ‘back to magical practices, origin and justification of that plastic representation forbidden by many religions’.64 In fact, as Mauss had argued, ‘[m]agic includes … a whole group of practices which we seem to compare with those of religion’.65 The entire panoply of the activities of the modern shaman and medieval magician that he gathers under his theory of magic – rites and ceremonies, incantations and spells, shape shifting, totemism, the varieties of mediumism, astrological prediction and other divination, sympathetic contiguity, the creation of magical recipes and talismans – would be carried out, engaged in, theorized, considered or represented in some way by Surrealists.66 As demonstrated by Aragon’s essay, however, there is no evidence in Surrealism’s trajectory up to 1930 of any serious reading in, or understanding and application of magic. Rather, Aragon seems to have been sharing in and contributing to an emerging language within the Paris group that made the movement’s growing interest in alchemy and magic more visible and positioned Surrealism as the palpable heir to occultism (or hermeticism) as traditionally understood and practiced. This is particularly marked in a text that was exactly contemporary with Aragon’s, namely Breton’s Second Manifesto of Surrealism (1930).67

Alchemy, clairvoyance and magic had been important to understanding creativity and practice for artists such as Victor Brauner, Max Ernst and Masson in the 1920s and 1930s.68 However it was only from the later 1930s, following their unhealable rift with organized communism, that the Surrealists’ own and others’ writing, art and experiences were consistently theorized by members of the group in a detailed manner. This took place through their increasing knowledge of pre-modern belief systems and greater understanding of the ways alchemy, the occult and magic had informed modern poetry, especially that of Victor Hugo, Charles Baudelaire, Mallarmé and Rimbaud. Ultimately, this would happen through recourse to Surrealist texts that identified and could potentially comprehend such phenomena (initially, unexplainable action-at-a-distance, second sight or precognition) through alternative causalities that were the domain of magic. As Mauss had pointed out with reference to Frazer: ‘magic gives every outward appearance of being a gigantic variation on the theme of the principle of causality’.69 Freud understood that, too, allowing the Surrealists to root coincidences in art and life in their own early exploration of the unconscious through automatic writing and drawing, and accordingly perceive them as forms of clairvoyance close to mediumism.70

In the absence of just about any feature of Cézanne’s art that could be latched onto positively by Surrealism, ‘magic’ in this sense became an inferential tool by which it could be assessed in the second half of the 1930s. I look at this subtext of Surrealist interpretation in my first chapter. The apparently unassailable ‘father’ of early twentieth-century art according to painters of that period and modernist critics who came after is well and truly berated there by Surrealists while functioning momentarily as an initial, revisionist test case for reimagining the nineteenth-century canonical artist as seer by none other than Breton himself in his Mad Love (1937).71 By then, the word ‘myth’ was virtually interchangeable with ‘metaphor’ in the movement due to those important writings by Breton from 1935 on myth, poetry, art and predestination, to be discussed in my second chapter, on René Magritte and Renoir.72

The outbreak of war forced consideration along the lines of esotericism of the epistemic failure of European civilization as it had during and after the First World War. The creation of a card pack following Breton’s research into the tarot at the time of the Surrealists’ passage through Marseille between 1939 and 1942, and Breton’s re-encounters with black writers soon after in Martinique, would ultimately lead to efforts to bridge the European and non-European traditions of magic. This endeavour was carried out by anti-colonial Surrealists who, at the time, perceived individuals of Afro-Caribbean descent, such as Wifredo Lam and Aimé Césaire, to be ancestrally close to magic. Breton’s text titled ‘De la survivance de certains mythes et de quelques autres mythes en croissance ou en formation’/‘On the Survival of Certain Myths and on Some Other Myths in Growth or Formation’, inserted into the catalogue of the exhibition First Papers of Surrealism mounted in 1942 in New York, introduced brief consideration of the Philosopher’s Stone, the Androgyne and tarot in connection with the poetry of Rimbaud and Gérard de Nerval, as well as the occultist apparition of the ‘new myth’ of the ‘Great Invisibles’, all of which would receive theoretical elaboration later.73

However, it was really the poet Benjamin Péret who extended Surrealist poetic theory fully from prophecy to non-modern magic specifically. This took place in his loosely written 1943 volume La Parole est à Péret, translated in an abridged form in the New York poets’ magazine View as ‘Magic: The Flesh and Blood of Poetry.’74 Composed in Mexico and meant as an introduction to a collection of myths, legends and folktales from Latin America, it presents an instance of Péret’s own purported precognition alongside the claim that ‘[t]he common denominator of the sorcerer, the poet and the madman cannot be anything else but magic’, in which the sorcerer is both the tribal shaman and medieval magician, as he had been for Mauss.75 ‘Primitive myths are largely made up of the residue of poetic illuminations, intuitions or omens’, Péret insisted, ‘confirmed in such a brilliant manner that they instantaneously penetrated to the depths of these peoples’ consciousness’.76 Heavily informed by Péret’s reading since at least 1931 of The Golden Bough, Totem and Taboo and probably Lévy-Bruhl, this publication was prefaced by a statement of solidarity that declared agreement with Péret’s conclusions, signed by seventeen Surrealists in nine countries in their absence and by Breton, Duchamp, Charles Duits, Ernst, Matta and Yves Tanguy in New York.77

The paradigm apparently established by Péret here was immediately taken up by View. In fact, that publication had affirmed in the leader of its previous number that the ‘artist should be understood as a contemporary magician’, ending with the declaration: ‘[s]eers, we are for the magic view of life’, presumably influenced by Péret’s recent text, which was advertised as forthcoming in the review on the back of that issue.78 It was explored further in Surrealism’s wartime periodical in America VVV (four issues, 1942–4). Meanwhile Breton’s book Arcane 17 took a major step towards formulating the movement’s shift towards esotericism by reinforcing in 1944 the charges made by the Manifesto of Surrealism twenty years earlier against ‘the realistic attitude, inspired by positivism’,79 through denunciation of the ‘monopolistic and intolerant character’ of the ‘positivist interpretation of myths’,80 declaring that, by contrast:

Esotericism, with all due reservations about its basic principle, at least has the immense advantage of maintaining in a dynamic state the system of comparison, boundless in scope, available to man, which allows him to make connections linking objects that appear to be farthest apart and partially unveils to him the mechanism of universal symbolism.81

Here Breton meant to place under the care of esotericism not only the longstanding complaint first made in the Manifesto against positivism, soon developed to encompass art in Surrealism and Painting,82 but also the definition of the image established in that document (after Pierre Reverdy) as ‘a juxtaposition of two more or less distant realities’.83 Following this intervention, the movement’s concerted shift towards magic, superstition and occultism or esotericism generally reached a wider public in the form of the International Exhibition of Surrealism or Le Surréalisme en 1947 held in Paris. Indeed, occultism specifically became a means of comprehending the totality of Surrealism in the writing of Michael Carrouges from that year.84

Let us remind ourselves that this culmination took place in the very year that Greenberg came to see as the one in which an American school of abstract artists was established.85 At the time, a few months after the closure of Le Surréalisme en 1947, he wrote as follows in an important statement that aspired towards what is now to us a familiar formulation of the logical extension of the French avant-garde into the contemporary American vanguard, along with an attempt to identify the predicament of the latter:

The Impressionists and those who came after them in France put themselves in accord with the situation [created by ‘bourgeois industrialism’] by implicitly accepting its materialism – the fact, that is, that modern life can be radically confronted, understood and dealt with only in material terms.… From now on you had nothing to go on but your states of mind and your naked sensations, of which structural, but not religious, metaphysical or historico-philosophical, interpretations were alone permissible. It is its materialism, or positivism … that made painting the most advanced and hopeful art in the West between 1860 and 1914 … The School of Paris rested on a sufficient acceptance of the world as it must be, and it delighted in the world’s very disenchantment, seeing it as evidence of man’s triumph over it. We, confronted more immediately by the paraphernalia of industrialism, see the situation as too overwhelming to come to terms with, and look for an escape in transcendent exceptions and aberrated states. True, it was a Frenchman who eminently taught the modern world this way out – but one suspects that one of the reasons for which Rimbaud abandoned his own path was the realization that it was an evasion, not a solution, and already on the point of becoming, in the profoundest sense, academic.86

Given the dominant themes of Surrealism’s Paris show and Breton’s standard references in his introductory catalogue essay to Rimbaud in his inventory of pre-Surrealist ‘visionaries’, this could almost be read as a direct rebuttal of Surrealism’s esotericism in 1947 if Surrealism had still mattered to Greenberg by that year.87 In fact, Greenberg had started to use the term ‘positivism’ to characterize modernism in 1944 at the time he launched his landmark attack on Surrealism.88 Although he was capable of acknowledging the importance of Surrealist painting to Jackson Pollock when it suited him, here in 1947 Pollock’s work was cordoned off as ‘positivist, concrete’ in spite of its quasi-Surrealist debt to ‘intuition’.89

A few months earlier, Greenberg had even managed to extend the opinion given here, that ‘in all great periods of art, scepticism and matter-of-factness take charge of everything in the end’, to a favourable but very strange review of the recent oeuvre of Victor Brauner.90 Shown at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York from 15 April till 1 May 1947, signature works on display were all from the previous two years and inspired by Brauner’s interest in mediumism and magic since 1939. However, this went entirely unmentioned by Greenberg in favour of their ‘flatter and tighter handling’ afforded by their main material, wax, and the ‘flat-patterned, ornamental, emblematic kind of painting’ on view, ‘that clings as closely to the picture surface as inlay work’, even as it is Paul Klee’s influence that takes up virtually all of the review.91 The suppression of their content by Greenberg extended to the text by Breton that was included in the catalogue for this first solo show of Brauner’s in America. It was ignored by Greenberg no doubt for its equally objectionable, reverie-like style and comparison of poets and artists with ‘mages, heretics [and] “initiates” of all sects’, and more so for Breton’s claim that the wax in Brauner’s pictures possessed the power of exorcism.92 Those were views entirely aligned with the current direction of Surrealism and supported by the artist’s own esoteric musings in the same catalogue.

In spite of the fragmentation of the Surrealist group during the war over the period of that recent work, the activities of Brauner had confirmed the new bearing of the movement. In the ‘altar’ he created for Le Surréalisme en 1947 he would construct (on Breton’s suggestion) a three-dimensional version of the ‘wolf-table’ that had appeared in two earlier paintings, called ‘neo-academic’ by Greenberg but thought divinatory by Breton.93 The same important role in Surrealism was played by the presence in America in the 1940s of the Swiss artist Kurt Seligmann. His wide-ranging knowledge of the history, theory and practice of magic accrued since the 1930s is confirmed in Seligmann’s articles in View and VVV from 1942, foreshadowing his major though often criticized study The Mirror of Magic (1948).94 They secured a central if temporary place for him in the movement in this transitional period, while he went completely uncited in Greenberg’s writings.

Seligmann’s disappearance from the history of art was confirmed by his omission from Breton’s L’Art magique. That absence would be baffling were it not for the disagreement between the artist and Breton early in 1943 over an interpretation of the tarot and Seligmann’s subsequent ejection from the Surrealist group, just as it was turning resolutely towards magic. Revising the Western canon and, more specifically, the modernist one, L’Art magique relocated both on the high altar of magic and it stands as the main statement on the subject within Surrealism. Breton’s introduction to the book leans heavily initially on Paracelsus and especially Novalis to trace a path for occultism and magic through the reading of Lévi in the modern period by poets Baudelaire, Mallarmé and Rimbaud, and the reception of the same ideas by Hugo, Nerval and Lautréamont.95 Breton opposed the functionalism, positivism and objectivism of Frazer, Mauss, Durkheim and even Freud by drawing upon the writings of those who were immersed in magic such as Lévi and Louis Chochod.96 This familiar difference between the academic study and rationalization of a subject area, on the one hand, and a purported practice by or experience of writers, artists and initiates, on the other, was also played out in the enquiry that accompanied the book. The difficulties Breton acknowledged in defining magic art in his introduction to L’Art magique are plain for all to see in his efforts to adapt to the theme a voluminous quantity of objects from across the world from prehistory to modernity, ending, of course, with Surrealism where magic is ‘rediscovered’. This along with Breton’s conclusion could have been predicted by anyone who had read his previous writings: magic in art was to be found in the same place as magic in poetry, in ‘the magico-biological character of metaphors’.97

Throughout Surrealism from the mid-1940s, then, culminating in L’Art magique, magic and (poetic) enchantment as traditionally understood, but substantiated often with reference to psychoanalysis, became the ground upon which Surrealist art criticism and art history could contest what the movement perceived broadly to be the ‘positivism’ of naturalism, Impressionism, classicism and socialist realism, and especially modernist formalism.98 By these alternative means, it reassessed and even claimed to return the unease to the art of some of those painters already domesticated by modernism. It is modernity we have to thank for those too-expansive categories as much as modernism as a critical paradigm itself. And because of that it was modernist positivism and modernity conceived as ‘the disenchantment of the world’ in Max Weber’s well-worn phrase – meaning secularization and the decline of magic with the escalation and intensification of capitalist utilitarianism, intellectualization and scientific, bureaucratic, legal and political rationalism under the banner of ‘progress’ – that Surrealism aimed to combat in its take up of magic and the occult and its location of a future for the human race in the past.

Surrealism’s first historian Walter Benjamin read Weber closely and one other sympathizer of the movement recently evoked this central critique of Weber’s to set up his defence of Surrealism as a ‘precise instrument’ for escape from the ‘rigid and narrow-minded confines of use value’.99 However, there is no evidence that Breton, Aragon or any other first generation Surrealist knew of Weber’s assertion of the dissolution of ‘mysterious incalculable forces’ with ‘increasing intellectualization and rationalization’ in what he called ‘Occidental culture’, entailing a society and civilization in which ‘one can, in principle, master all things by calculation’.100 Yet, like Surrealism itself, it was a contention determined by the mechanized catastrophe of the First World War. Made at the very moment Surrealism was being born, Weber’s interpretation of modernity diagnosed the movement’s future theoretical orientation, which would in turn determine a unique and still-obscure critical history of fin-de-siècle painting fashioned from poetry, psychoanalysis, dialectics and ultimately, and most significantly, a range of esoteric theories. Its reconstruction in the pages that follow is shaped by the diverse tools made available by art history, literary theory and social and intellectual history, mainly, and is meant to acknowledge and engage with contemporary scholarship in those fields, as well, more specifically, as with the histories and theories of Surrealism, modernism and studies of enchantment, magic and occultism.

1See José Pierre, André Breton et la peinture, Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme, 1987, 20–3. Redon’s work left its trace in that of Marcel Duchamp (the paintings of 1910–11), André Masson and Yves Tanguy, yet André Breton’s attraction to Moreau is much better known and more often explained than his resistance to Redon, which José Pierre failed to break: Pierre, André Breton et la peinture, 23. For Surrealists, it seems that the resemblance between Redon’s work and Surrealist painting was superficial, like the comparison with Grandville’s, and, worse, ‘aestheticist’, decorative and a mere fabrication of mysteries and dreams, complaints that were documented most comprehensively soon after the Redon exhibition held at what was then the Orangerie des Tuileries from October 1956 till January 1957 (and made in contrast with the art of Moreau, Kubin and Munch) by the Surrealist Jean-Louis Bédouin, ‘Trop d’honneur’, Le Surréalisme, même, no. 2, spring 1957, 100–4. Years later, Redon came out second best to Moreau on mainly formal grounds in a survey of pre-Surrealist art by José Pierre, L’Univers surréaliste, Paris: Somogy, 1983, 56–7. Also see the alternative (meaning more favourable) discussion of Redon and Grandville by Stefanie Heraeus, ‘Artists and the Dream in Nineteenth-Century Paris: Towards a Prehistory of Surrealism’, trans. Deborah Laurie Cohen, History Workshop Journal, no. 48, autumn 1999, 151–68.

Obviously, Symbolist poetry and theory are important to this book but they are diverted to its aims, which are to rethink early modernist art after Surrealism; so in my fourth and fifth chapters, for instance, I construe the ‘surrealist’ qualities of the work of Georges Seurat and Paul Gauguin partly by recourse to an essay by Breton devoted to Symbolist poetry that assessed its relevance in the twentieth century according to how far it adhered to the Surrealist marvellous as against the manufactured ‘mystery’ of Symbolism (which the dated work of the ‘bourgeois’ ‘pseudo voyant’ Redon fell foul of in Bédouin’s analysis): André Breton, ‘Marvellous versus Mystery’ [1936], Free Rein [1953], trans Michel Parmentier and Jacqueline d’Amboise, Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1995, 1–6.

2The nearest to a joined up discussion are the passages given over mainly to Gauguin in Pierre, André Breton et la peinture, 26–8, 31–2. Also see the equally brief material on Seurat and mainly Gauguin in Pierre, L’Univers surréaliste, 57–61.

3See, for instance, the monographic chapters that uncritically assess van Gogh, Seurat, Cézanne and Gauguin along contextual lines (scientific, political, ideological and occultist) while leaving the canon secure in Albert Boime, Revelation of Modernism: Responses to Cultural Crises in Fin de Siècle Painting, Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press, 2008.

4For a more detailed account than is possible or necessary here of the history, intricacies and fate of ‘formalism’, mainly in the writings of Clement Greenberg, see Caroline A. Jones, Eyesight Alone: Clement Greenberg’s Modernism and the Bureaucratization of the Senses, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2005, 60–95.

5I am thinking primarily of the major exhibition, both historical and contemporary, organized by the movement and titled Surrealist Intrusion in the Enchanters’ Domain held at the D’Arcy Galleries on Madison Avenue in New York from 28 November 1960 till 14 January 1961; also the influential article questioning any possibility of a Surrealist painting based on technique by Max Morise, ‘Enchanted Eyes’ [‘Les Yeux enchantés’] [1924], Mary Ann Caws (ed.), Manifesto: A Century of Isms, Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2001, 478–81; and even René Magritte’s major commission executed for the casino at Knocke-le-Zoute in Brussels in 1953 consisting of reheated Magrittean iconography and titled The Enchanted Realm or Domain (Le Domaine enchanté). There was also the major exhibition and catalogue that partly revived Surrealism in Britain: The Enchanted Domain, Exeter: Exe Gallery, 1967.

6See the remarks on Fénéon and Kahn made by Sven Lövgren, The Genesis of Modernism: Seurat, Gauguin, van Gogh and French Symbolism in the 1880s, trans. Albert Read, Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1959, 63, 66. For the significance of the year 1891 in this and the role of Camille Pissarro, see T. J. Clark, Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999, 71–7.

7‘les surréalistes auraient souscrit sans hésiter’, Pierre, L’Univers surréaliste, 57.

8Paul Gauguin, The Writings of a Savage [1974], ed. Daniel Guérin, trans. Eleanor Levieux, New York: The Viking Press, 1978, 140–1. Further discussion and approval within Surrealism, beyond Pierre’s remark, of Gauguin’s rejection of Impressionism can be found in Gérard Legrand, Gauguin, Paris: Club d’Art Bordas, 1966, 43–4. For a full study of Gauguin’s six years as an Impressionist up to 1885, see Richard R. Brettell and Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark, Gauguin and Impressionism, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2005.

9Gauguin, Writings of a Savage, 141.

10Gauguin’s statement about the Impressionist artists were first put into circulation in 1906 when quoted in the very early monograph on the artist by Jean de Rotonchamp, Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903, Paris: Édouard Druet et Cie, 1906, 210. For the Surrealists’ reverence for the great tableau as ‘une des plus grandes peintures de tous les temps’, see Legrand, Gauguin, 31.

11See the editor’s remarks in André Breton, Oeuvres complètes, vol. 1, Paris: Gallimard, 1988, 1317, 1320.

12André Breton, ‘Surrealism and Painting’ [1925–8], Surrealism and Painting [1965], trans. Simon Watson Taylor, New York: Harper & Row, 1972, 1–48, 4.

13Letter to Émile Bernard of about 26 November 1889 in Vincent van Gogh, The Letters: The Complete Illustrated and Annotated Edition, Vol. 5: Saint-Rémy-Auvers 1889–1890, eds Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten and Nienke Bakker, London and New York: Thames & Hudson, 2009, letter 822, 146–53, 148. This approach to art lamented by van Gogh was characteristic of Gauguin: before going to meet van Gogh in Arles, he had offered the following patronizing advice in a letter to his friend Émile Schuffenecker on 14 August the previous year: ‘A hint – don’t paint too much direct from nature. Art is an abstraction! study [sic] nature then brood on it and treasure the creation which will result, which is the only way to ascend towards God – to create like our Divine Master’, Paul Gauguin, Letters to his Wife and Friends [1946], ed. Maurice Malingue, trans. Henry J. Stenning, Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2003, 100–1, 100. Evidence that Gauguin’s position as spelt out here was known to the Surrealists can be found in Legrand, Gauguin, 11.

14‘Threat is piled upon threat, one yields, abandons a portion of the terrain to be conquered. This imagination which knows no bounds is henceforth allowed to be exercised only in strict accordance with the laws of an arbitrary utility’, André Breton, ‘Manifesto of Surrealism’ [1924], Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972, 1–47, 4; Victor Merlhès, Correspondance de Paul Gauguin: Documents, témoignages, Paris: Fondation Singer-Polignac, 1984, 275.

15Breton, Surrealism and Painting, 4.

16Breton, Surrealism and Painting, 6.

17André Breton, ‘Conférences d’Haïti, III’ [1946], André Breton, Oeuvres complètes, vol. 3, Paris: Gallimard, 1999, 233–51, 237.

18‘L’impressionnisme, comme mouvement de réaction contre ceux qui l’ont précédé, répudie en effet l’imagination romantique et tout ce que les peintres nomment en mauvaise part la littérature. Indifférents à la philosophie comme à la poésie, les peintres impressionnistes prétendent ne peindre que ce qu’ils voient et comme ils le voient, en s’attachant surtout à l’eau, au ciel et aux brumes, autrement dit à tout ce que le temps fait et défait indéfiniment. La trouvaille, fruit du simple hasard comme presque toujours, qui a donné essor à l’impressionnisme semble bien avoir été l’observation d’abord distraite et tout involontaire du reflet d’un paysage dans l’eau d’une rivière’, Breton, Oeuvres complètes, vol. 3, 235–6. Breton was referring at the end of this passage to the studies of water carried out by Monet and Renoir at the floating restaurant and bathing place La Grenouillère late in 1869: John Rewald, The History of Impressionism [1946], New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1973, 226–32.

19‘révolution visuelle’, Breton, Oeuvres complètes, vol. 3, 236.

20See the letter of 27 October 1945 sent to Victor Brauner in which Breton writes of himself and Duchamp leafing through Cahiers d’Art before concluding ‘all works of art which make the slightest concession to the physical, to the physical aspect of things, to models nude or dressed, landscapes, still-lives, etc. … and whatever distortion to which they may give rise, must be pitilessly shunned. All of that smacks of the vainest sort of Impressionism. Today, this must be the sole measure of judgement’, quoted in Didier Semin, ‘Victor Brauner and the Surrealist Movement’, The Menil Collection (ed.), Victor Brauner: Surrealist Hieroglyphs, Hatje Cantz: Ostfildern-Ruit, 2001, 23–41, 34 (translation slightly modified).

21Clement Greenberg, ‘Surrealist Painting’ [1944], The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 1, Perceptions and Judgements, 1939–1944, ed. John O’Brian, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1986, 225–31. For Greenberg’s measured ‘banishment’ of Surrealism in the 1940s, in which ‘[f]ormalist innovation trumps Surrealist malingering’, see Jones, Eyesight Alone, 67–9.

22André Breton, ‘Concerning Symbolism’ [1958], Surrealism and Painting, 357–62, 357.

23‘Nouvelle manière de voir, de sentir, d’aimer la nature’, ‘ici l’imagination reprend ses droits’, André Masson, ‘Monet le fondateur’, Verve, vol. 7, nos. 27/28, December 1952, 68. ‘The imagination is perhaps on the point of reclaiming its rights’, Breton, Manifestoes, 10 (translation modified). His editor has expressed the view that Masson’s enthusiasm for Impressionism was affected by renewed debates about automatism in France due to the advent of ‘lyrical abstraction’ (to be surveyed in my fifth chapter): André Masson, Le rebelle du surréalisme: écrits, ed. Françoise Will-Levaillant, Paris: Hermann, 1976, 195 n. 127. Masson was quoted a few years later in the formalist account of Monet as one of ‘the great precursors who put forth the premises which culminated in abstract painting’ and viewed ‘[t]he optical qualities of Impressionism’ as ‘integral to the abstract painting of the forties and fifties’, William Seitz, ‘Monet and Abstract Painting’, College Art Journal, vol. 16, no. 1, Autumn 1956, 34–46, 45, 34, 35. Seitz was probably prompted by the ‘late’ Monet exhibition at Knoedler in New York as was another champion of abstract expressionism who also mentioned Masson’s text and viewed the vogue for Monet as a change of heart by formalist criticism brought about by the success of American abstraction: Thomas B. Hess, ‘Monet: Tithonus at Giverny’, Art News, vol. 55, no. 6, October 1956, 42. See the text that dates the origin of the Monet revival in America to 1955 and its culmination in exhibitions in 1957 and the major Monet show of 1960 at MOMA in New York that went to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art: Michael Leja, ‘The Monet Revival and New York School Abstraction’, London: Royal Academy of Arts, Monet in the 20th Century, 1998, 98–108 and 291–3, 103. For the critical reception of Impressionism before and after abstract expressionism, see Mary Tompkins Lewis, ‘Introduction: The Critical History of Impressionism: An Overview’, Mary Tompkins Lewis (ed.), Critical Readings in Impressionism and Post-Impressionism: An Anthology, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2007, 1–19, 10–14. Greenberg’s main contribution to the reconsideration of Monet and Impressionism can be found in Clement Greenberg, ‘“American-Type” Painting’ [1955], The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 3, Affirmations and Refusals, 1950–1956, ed. John O’Brian, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1993, 217–36, 228, 229–32.

24Breton, Surrealism and Painting, 360. The deep roots of the advancement of Gauguin ahead of Impressionism, as Breton must have been aware as a reader of the Mercure de France, lie in the article by Albert Aurier, ‘Le Symbolisme en peinture: Paul Gauguin’, Mercure de France, tome 2, March 1891, 155–65.

25Impressionism, Breton wrote, ‘shares with naturalism the characteristic of attempting to achieve a position of subservience in relation to positivism: “It is a question of painting humbly, stupidly, the plays of light which pass before the artist’s eyes,”’ Breton, Surrealism and Painting, 360. Breton was quoting here from the passage in which Impressionism was viewed as ‘une des phases du mouvement positiviste’ and the Impressionist painter said to paint ‘humblement, bêtement’ the play of light: Charles Chassé, Le Mouvement symboliste dans l’art du XIXe siècle, Paris: Librairie Floury, 1947, 19. For a rejection of the crudeness of such pronouncements as Chassé’s (made by some as early as the 1890s), channelled through Camille Pissarro, along with the counter-intuitive suggestion that ‘Monet’s art is driven not so much by a version of positivism as by a cult of art as immolation’ that is flavoured by the mood evoked by the likes of (Surrealist hero) Gérard de Nerval, see Clark, Farewell to an Idea, 71, 129, 12; and for a longer discussion of positivism, Impressionism and Symbolism embedded in a larger argument stating that ‘Symbolism and Impressionism, as understood around 1890, were not antithetical’, see Richard Shiff, Cézanne and the End of Impressionism: A Study of the Theory, Technique, and Critical Evaluation of Modern Art, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1984, 7, 11, 23–6. Breton quoted Odilon Redon from the book he owned by Chassé, Le Mouvement symboliste, 48; Chassé repeated it a few years later in another book Breton owned (signed by the author), Les Nabis et leur temps (1960): ‘Paul Sérusier several times repeated to me this sentence of Redon’s: “I refused to embark on the Impressionist boat because I found the ceiling too low”’, Charles Chassé, The Nabis & their Period [1960], trans. Michael Bullock, London: Lund Humphries, 1969, 26; Redon’s quotation showed its durability by appearing yet again in the survey of pre-Surrealist art by Pierre, L’Univers surréaliste, 57. In 1913, Redon held forth on the artists of his generation as follows: ‘True parasites of the object, they cultivated art on a uniquely visual field, and in a certain way, closed it off from that which goes beyond it, and which might bring the light of spirituality into the most modest trials’, Odilon Redon, To Myself: Notes on Life, Art and Artists [1979], trans Mira Jacob and Jeanne L. Wasserman, New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1986, 110. Redon can be found debating the point with the Nabis led by Sérusier at the Galerie Vollard in Maurice Denis’s 1900 painting Homage to Cézanne, in which canvases by Renoir and Gauguin also appear (it was painted in the midst of Denis’s attempt to accommodate theoretically the early moderns to classicism: Maurice Denis, Théories, 1890–1910: Du symbolisme et de Gauguin vers un nouvel ordre classique [1912], Paris: L. Rouart et J. Watelin, 1920). Redon was considered as equally parasitical as the Impressionists by Bédouin who aimed to demonstrate this by contrast with Gauguin and with reference to that artist’s letter of August 1901 sent to Daniel de Monfreid in which Gauguin avowed: ‘il y a en somme en peinture plus à chercher la suggestion que la description, comme le fait d’ailleurs la musique’ (oddly, Bédouin omitted Gauguin’s joke about Redon being senile and possessed of a depleted, one-note imagination that led up to this famous, Symbolism-inspired passage): Bédouin, ‘Trop d’honneur’, 101–2; Paul Gauguin, Lettres de Gauguin à Daniel de Monfreid, Paris and Zurich: Éditions Georges Crès et Cie, 1918, 321–8, 325–6.

26Breton, Surrealism and Painting, 361.

27Breton, Surrealism and Painting, 360.

28‘Seurat’s planar and often geometric forms encourage us to stress his importance as a forebear of modern abstract art’, Robert L. Herbert, ‘Seurat’s Drawings’, Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, Seurat: Paintings and Drawings, 1958, 22–5, 24. I note in my third chapter the important scholarship on Seurat and Jules Chéret by Herbert who was by no means a passive formalist, as underlined by Paul Smith, ‘Introduction’, Paul Smith (ed.), Seurat Re-Viewed, University Park PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009, 1–13, 5–6.

29Breton, Surrealism and Painting, 361.

30André Breton, ‘Alfred Jarry as Precursor and Initiator’ [1951], Free Rein, 247–56, 252–3. Jarry had met Gauguin with the poet Léon-Paul Fargue in 1893 and devoted three poems to paintings by Gauguin that year: Alastair Brotchie, Alfred Jarry: A Pataphysical Life, Cambridge, Mass. and London: MIT, 2011, 41. His esteem for the artist is declared in chapter 17 of Alfred Jarry, Exploits & Opinions of Doctor Faustroll, Pataphysician [pub. 1911], trans. Simon Watson Taylor, Boston: Exact Change, 1996, 43–4 (Denis and Bernard are also noted in passing or among the many dedicatees in the book). It should be added that critics such as André Fontainas and Jules Antoine also isolated the same four artists among a few others in the 1890s as recorded by Nathalie Heinich, The Glory of Van Gogh: An Anthropology of Admiration, trans. Paul Leduc Browne, Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996, 15, 23.

31Guillaume Apollinaire, ‘Bernheim-Wagram’ [1907], Apollinaire on Art: Essays and Reviews 1902–1918 [1960], ed. Leroy C. Breunig, trans. Susan Suleiman, Boston, Mass: MFA, 2001, 17–18, 18. For the importance of Apollinaire as an art critic to Breton, see Pierre, André Breton et la peinture, 36–50.

32‘Se rappeler qu’un tableau – avant d’être un cheval de bataille, une femme nue, ou une quelconque anecdote – est essentiellement une surface plane recouverte de couleurs en un certain ordre assemblées’, Maurice Denis, ‘Définition du néo-traditionnisme’ [1890], Théories, 1–13, 1.

33Breton, Surrealism and Painting, 362.

34Charles Estienne, ‘De Sérusier le nordique à Kandinsky l’oriental’, Combat, no. 880, 7 May 1947, 2. The legendary quotation was mobilized by a former Surrealist in the 1970s to assert what Breton claimed, more or less, in Dessins Symbolistes, that formalism since Denis ‘tends to regard [Symbolism/Surrealism] with extreme disdain even to the point of trying to eliminate [them] historically’, José Pierre, Symbolism, [1976], trans. Désirée Moorhead, London: Eyre Methuen, 1979, n.p.

35‘le travestissement des sensations vulgaires – des objets naturels, – en icons sacrées, hermétiques, imposantes’, Denis, Théories, 12.

36Roger Fry, ‘The Post-Impressionists’, London: Grafton Galleries, Manet and the Post-Impressionists, 1910, 7–13, 10, 11. Its sequel of 1912, the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition, was subtitled British, French and Russian Artists and gave equal coverage and pre-eminence to Cézanne but not the others (van Gogh has only one work listed in the catalogue and there are none by Gauguin), since the intention was to display the ‘moderns’ not the ‘masters’. Nevertheless, the essays on those moderns by Clive Bell and Fry revelled in the victory of ‘simplification and plastic design’, ‘logical structure’ and ‘closely-knit unity of texture’ over content (though not the one on Russian art by the mosaicist Boris von Anrep, which included some cultural context for the Russian works on show and gave notice of the importance of the imagination in their creation) to the point that Bell’s bathetic coal-scuttle has no symbolism for artists let alone ‘magic’ worth reporting and its significance for them lies only in its form and what that can ‘express’ of ‘the toes of the family circle and the paws of the watchdog’, Clive Bell, ‘The English Group’ and Roger Fry ‘The French Group’, London: Grafton Galleries, Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition, 1912, 21–4, 22; 25–9, 26. For some contrast, see the remarks made the following year on the chimney flue as ‘“the most strange, the most bizarre subject”’ to the painter of ‘two realities’, as stated by Rodolphe Bresdin in 1864 and recalled by his student Redon, To Myself, 109, 110. Van Gogh and Gauguin were the two main artists treated as ‘post-impressionists’ by Albert Barnes in 1927; Barnes gave Cézanne a section of his own with some reservations while Seurat is alluded to only briefly and it is Courbet, Manet, Monet and Pissarro who are said to be the initiators of modern art through this phrase: ‘[t]he chief point of difference between the old and the new may be said to be that the moderns exhibit greater interest in relatively pure design’, after which the typically formalist language of ‘plastic elements’, ‘structural values’, ‘organic wholes’ and so on ensues: Albert C. Barnes, The Art in Painting, London: Jonathan Cape, 1927, 239.

37Meyer Schapiro, ‘The Introduction of Modern Art in America: The Armory Show’ [1952], Modern Art, 19th and 20th Centuries: Selected Papers, vol. 2, London: Chatto & Windus, 1978, 135–78, 160.

38Lewis (ed.), Critical Readings in Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, 12.