Plate 8

GREEK ORNAMENT

Greece, or Hellas, consisted of a number of small states, speaking the same language, and worshipping the same gods. Almost the whole of the Ægean coast of Asia Minor was occupied in early times by Greek Colonies, which supplanted those of the Phœnicians of Tyre and Sidon. The southern portion of this seaboard was occupied by the Dorians, and the northern by Ionians. In the course of time other Greek settlements were made on the Black Sea and Mediterranean coast of Asia Minor, as well as at Syracuse, Gela and Agrigentum in Sicily, and in Etruria and Magna Grecia in Italy. These colonies appear to have reached a higher state of art at an earlier period than Greece itself. The ascendancy in art in Greece was enjoyed by the Dorians circa 800 B.C. ; after which Sparta took the lead but was in turn excelled by the Ionians, when Athens became the focus of Greek art, and attained a degree of perfection in that respect that has remained unequalled to this day. Athens was destroyed by the Persians under Xerxes, 480 B.C. ; but under Pericles (470-429 B.C.) Greek art reached its culmination.

The abundant, although fragmentary, remains of Grecian architecture, sculpture, and the industrial arts show most vividly the artistic feeling and culture of the early Greeks, with their great personality and religious sentiment, in which the personal interest of the gods and goddesses was brought into relation with the life and customs of the people. Their myths and traditions, their worship of legendary heroes, the perfection of their physical nature, and their intense love of the beautiful, were characteristic of the Greek people, from the siege of Troy to their subjection by Rome, 140 B.C. The almost inexhaustible store of Greek art, now gathered in the British and in other European museums, furnishes one of the most valuable illustrations of the many glorious traditions of the past. The vitality of conception, the dignity and noble grace of the gods, the consummate knowledge of the human figure, and the exquisite skill of craftsmanship, are here seen in the greatest diversity of treatment and incident.

The work of Phidias, the most renowned of Greek sculptors, is largely represented in the British Museum by noble examples, showing his great personality, wonderful power, and his remarkable influence upon contemporary and later plastic art.

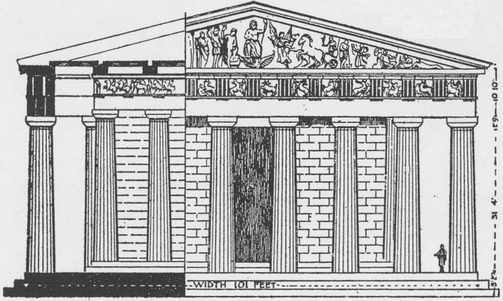

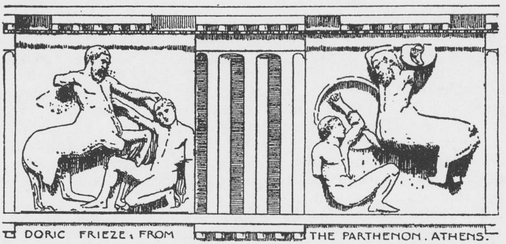

The Parthenon, or temple of the goddess Athene (plan, plate 85), which was built upon the Acropolis at Athens by Ictinus and Callicrates, 454-438 B.C., was enriched with splendid works of sculpture by Phidias. Many of the originals are now in the British Museum forming part of the Elgin Marbles, which were purchased from the Earl of Elgin in 1815. The two pediments of the temple contained figure sculpture in the round, larger than life size. The Eastern group represents the birth of Athene, and the western group the contest of Athene and Poseidon for the soil of Attica. The fragments of these pedimental groups are now in the British Museum, and though sadly mutilated, show the perfection of sculpture during the Phidian age. Of the 92 square metopes sculptured in high relief that enriched the Doric frieze, 15 are included in the Elgin Marbles. The subject represented on these metopes was the battle between the Centaurs and Lapithæ—a fine example of composition of line and mass, and dramatic power of expression.

ELEVATION OF THE PARTHENON. ATHENS.

The continuous frieze upon the upper part of the cella wall, under the colonnade or Peristyle, was 40 feet from the ground 40 inches in height, and 523 feet in length. It was carved in low relief, the subject being the Panathenaeic procession, the most sacred and splendid of the religious festivals of the Ancient Greeks. This frieze, with its rhythm of movement and unity of composition, its groups of beautiful youths and maidens, sons and daughters of noble citizens, its heroes and deities, heralds and magistrates; its sacrificial oxen, and its horses and riders is doubtless a most perfect production of the sculptors’ art. Each figure is full of life and motion, admirable in detail, having an individuality of action and expression, yet with a unity of composition, appropriate to its architectural purpose as a frieze or band.

The Parthenon, however, was but the shrine of the standing figure or statue of the goddess Athene, which was 37 feet high, and formed of plates of gold and ivory, termed Chryselephantine sculpture. Probably owing to the intrinsic value of the material, this work of Phidias disappeared at an early date.

Among the examples of sculptured marbles in the British Museum is the beautiful frieze from the interior of the Temple of Apollo at Bassae or Phigaleia erected by Ictinus, 430 B.C. This frieze, which shows an extraordinary vitality and movement, is 101 feet long and consists of 23 slabs  inches in width, the incidents depicted being the battle of the Greeks and the Amazons, and the contest between the Centaurs and the Lapithae. The dignity and reserve of the Parthenon frieze is here replaced by activity and energy of line and an exuberance of modelling.

inches in width, the incidents depicted being the battle of the Greeks and the Amazons, and the contest between the Centaurs and the Lapithae. The dignity and reserve of the Parthenon frieze is here replaced by activity and energy of line and an exuberance of modelling.

Some of the marbles in the British Museum are from the Nereid Monument of Xanthos, 327 B.C., so called because the female figures display moist clinging garments, and have fishes and seabirds between their feet. These sculptures show a high degree of perfection, and were probably the work of the Athenian sculptor, Bryaxis.

Among other examples of the Greek treatment of the frieze, is that of the Erechtheum, 409 B.C., with its black Eleusinian stone background, and white marble reliefs. The Temple of Nike Apteros, of about the same date, is noted for the beautiful reliefs from the balustrade which crowned the lofty bastion on which the temple stands. An example of Nike or victory, adjusting her sandal is here given. These reliefs are remarkable for their delicacy and refinement of treatment, and the exquisite rendering of the draped female figure. Other friezes now in the British Museum are from the Mausoleum erected by Artemisia to her husband, Mausolus, 357-348 B.C. This tomb consisted of a solid basement of masonry, supporting a cella surrounded by a colonnade of 36 columns. The upper part of the basement was enriched with a frieze illustrating the battle of the Centaurs and Lapithæ ; the frieze of the cella was illustrated with funeral games in honour of Mausolus. Seventeen slabs of the frieze of the order from the colonnade are in the British Museum ; they represent the battle of the Greeks and Amazons. In their composition these slabs show extraordinary energy of movement and richness of invention. This frieze differs absolutely from the Parthenon frieze in its fertility of incident and intensity of action. Bryaxis, the sculptor of the Nereid monument executed the north frieze, while the south was by Timotheus, the east by Scopas, and the west by Leochares.

A remarkable building, where again the frieze was an important feature, was the great altar at Pergamos, erected by Eumenes II., 168 B.C. This had a basement of masonry 160 feet by 160 feet, and 16 feet high, enriched with a sculptured frieze  feet high. The subject is the Gigantomachia, or battle of the gods and giants ; the treatment being characterized by passionate energy and expression, and daring skill in grouping and technique. Ninety-four of the original slabs of this frieze are now in the Berlin Museum.

feet high. The subject is the Gigantomachia, or battle of the gods and giants ; the treatment being characterized by passionate energy and expression, and daring skill in grouping and technique. Ninety-four of the original slabs of this frieze are now in the Berlin Museum.

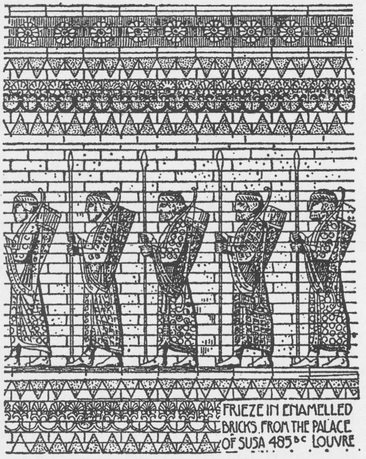

The frieze was an important decorative feature with the Assyrians and Greeks. The continuity of incident and rhythm of movement that was possible with the continuous frieze, together with its functional use of banding, no doubt tended to preserve its traditional form, hence we have many remains from antiquity of this beautiful decorative treatment. An early and fine example is the frieze of Archers from the palace of Susa, 485 B.C., now in the Louvre. This frieze, of which an illustration is here given, was executed in enamel on beton. A dignity of conception and unity of composition were here combined with skilful modelling of relief work, and fine colouring of blue, turquoise and yellow. This treatment of the frieze no doubt influenced the later work of the Greeks, who so nobly carried on this tradition of the frieze.

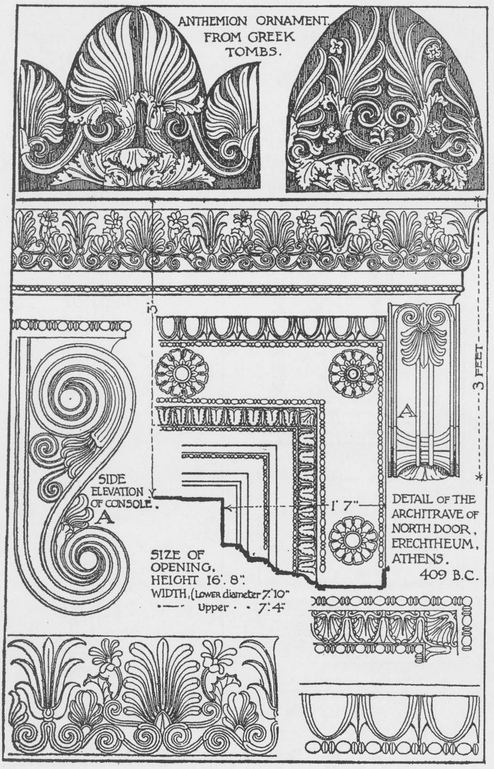

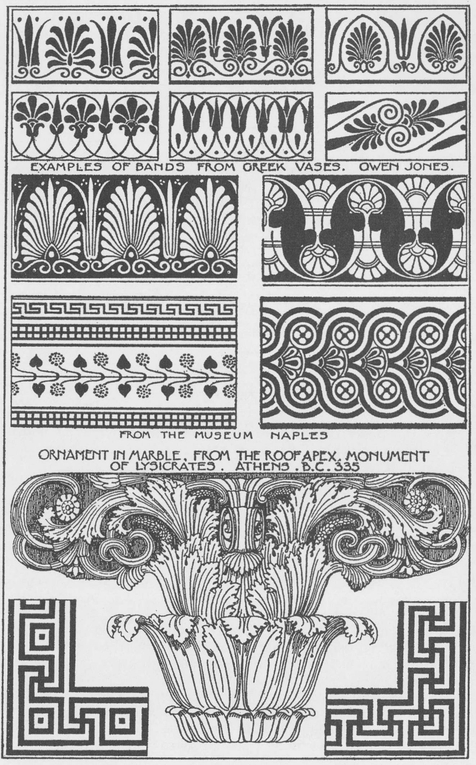

Greek ornament is distinguished by simplicity of line, refinement of detail, radiation of parts, unity of composition, and perfect symmetry. The anthemion, which is the typical form, differs from the earlier Lotus type in its more abstract rendering and its absence of symbolism ; it has a charm of composition and a unity and balance of parts.

The anthemion was sculptured upon the top of the funeral stele (figs. 1, 2, and 5, plate 8), upon the architrave of doorways (fig. 6), and above the necking of the Ionic columns (plate 6), or painted upon the panels of the deep coffered ceilings. It was also used in a thousand ways upon the many fine vases and other ceramic wares of that period. The simplicity and beauty of the anthemion and its ready adaptability, has doubtless rendered it one of the best known types of ornament. Like the Egyptian and Assyrian prototypes the Greek anthemion is usually arranged with alternate flower and bud, connected by a curved line or more frequently by a double spiral. Illustrations are given on plates 8 and 9 of a few typical examples, where the rhythm and beauty of composition are indicative of the culture and perfection of Greek craftsmanship.

Another feature, which at a later period received considerable development, was the scroll given on plate 9, which is a fine example from the roof of the monument to Lysicrates. The scrolls, cut with V-shaped sections, spring from a nest of sharp acanthus foliage. This scroll is formed of a series of spirals springing from each other, the junction of the spiral being covered by a sheath or flower ; the spiral itself being often broken by a similar sheath.

Plate 9

This spiral form, with its sheathing, is the basis of the Roman and Italian Renascence styles, and sharply differentiates them from the Gothic ornament, in which the construction line is continuous and unbroken.

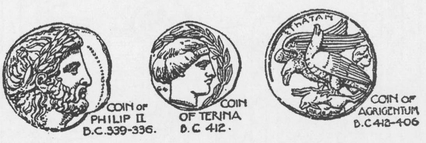

The rosette, a survival of the early Greek form, found at Crete, (1600 B.C.) was frequently used upon the funeral stele and the Architrave (plate 8) where its circular and radiating form contrasts beautifully with the functional straight lines of architectural design. The extraordinary vitality and versatility of the Greek craftsman may be traced through a magnificent series of coins dating from 700 B.C. to 280 B.C. The interest of subject, beauty of composition and largeness of style, combined with the utmost delicacy of technique, of these gold, silver, and electrum coins, are a reflex of the artistic feeling for beauty of the early Greeks.

Colour, as well as form, was a great factor in the art of the Greeks ; their architecture and sculpture were enriched and accentuated by the judicious use of beautiful colour. The Parthenon, with its simple and refined Doric architecture and magnifi-cent sculpture by Phidias, was enhanced by colour, which was introduced in the background of the pediment and the frieze, and also upon the borders and accessories of the draperies. The “ Lacunaria,” or sunk panels of the ceilings, were frequently enhanced with blue, having rosettes or stars in gold or colour. A frank use of pure colour was almost universal in early Egyptian and Assyrian art, and the Greeks were not slow to avail themselves of any art that was beautiful.

GREEK VASE OF THE STYLE OF NICOSTHENES (v. p. 107).