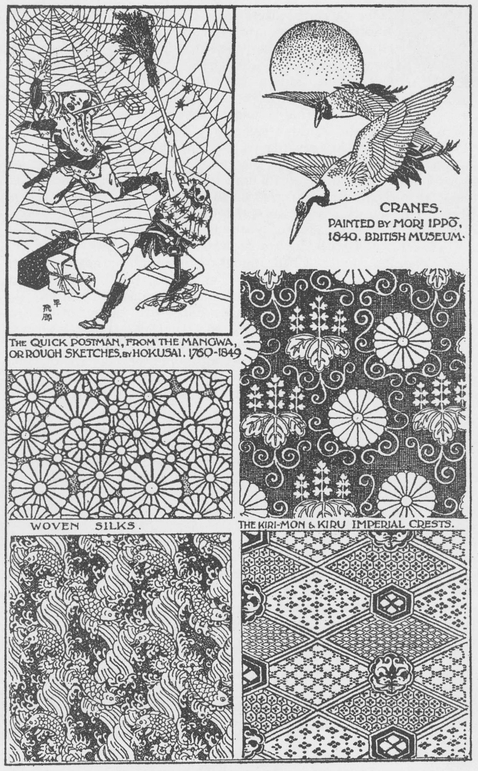

Plate 53

JAPANESE ORNAMENT

The arts of Japan, though doubtless owing their origin to China, are differentiated by a keener observation of nature and a more literal treatment of landscape, bird and animal life, and the beautiful flora of the country—the “ kiku ” or chrysanthemum, the “ botan ” or peony, the “ kosai ” or iris, the “ yuri ” or lily, the “ kiri ” or paulawina imperialis (somewhat resembling our horse chestnut), the “ matsu ” or fir, and the “ take ” or bamboo—likewise the peacock, the crane, the duck, the pheasant, and many smaller beautiful birds, together with reptiles, insects, and fishes ; all are elements in the decorative arts, being rendered with remarkable fidelity and delicacy of touch, united with a fine feeling for composition of line.

Physical phenomena, such as the snow-clad mountain, Fujiyama, have always exercised considerable influence upon the Japanese mind. This may be readily seen in the thirty colour prints by Hiroshige, and the hundred views of this mountain by Hokusai. The cherry and plum blossoms, emblems of the beauty and purity of spring, are also intimately associated with the life and the ornament of the people. It is this literal treatment of natural types, the marvellous technique, and especially the significance of the forms chosen, that constitutes the charm of the earlier Japanese art. It is singular that the materials used by the Japanese should be of little intrinsic value. Having no jewellery, they use little of the precious metals ; iron, bronze, enamels, clay, wood, and lac being the chief materials utilized in the decorative arts of Japan. Bronze is one of the earliest materials used in the arts of Japan, and their large statue of Buddha at Kamakura, cast in A.D. 748, rests upon a lotus flower with fifty-six petals, 10 ft. by 6 ft., and the height from base to top of figure is 63 ft.

Pottery made but little development until the 13th century, when a coloured earthenware, having but little decoration, was produced at Seto, in Owari, and it was not until 1513 that porcelain was introduced from China into Arita, by Shondzui ; and at the commencement of the 17th century a fine porcelain, decorated with birds and flowers in blue, red, and gold, now known as “ Old Japan ” or “ Old Hizen,” was produced. Kioto, Seto, and Arita were also noted for the production of a fine blue-and-white porcelain.

Cloisonné enamels, introduced in the 17th century, reached a high degree of technical excellence, but never quite reached the beauty, purity, and harmony of colour that characterized the old Chinese cloisonné.

Lacquer developed in Japan during the Heian period (A.D. 782-1192). The Ashikaga period (A.D. 1336-1573) saw the rise and progress of lacquer decoration in relief; and in the Tokugarva period (1615-1867) the technical skill of the craftsmen reached a high water mark. Towards the middle years of the 18th century an abundance of detail overwhelmed the old simplicity of motif.