Let’s think about physics for a moment. Power. You’ll remember that power is taking a force (this happens when chemical energy is converted into mechanical energy) and moving something a particular distance in a given time. The force over a distance is called work, and power is the rate that the work gets done. If you lift a weight of 50 pounds (22 kg) up vertically 3 feet (1 m), you’ve done 150 foot-pounds (203 J) of work. If you accomplish this task in 5 seconds, the power output is 30 foot-pounds (41 J) per second. We express power in terms of watts, named after James Watt, the Scottish engineer who developed the first practical steam engine.1 As he was trying to sell his new invention, prospective buyers wanted to know how many horses his engine would replace. He estimated that a draft horse could create a 150-pound (68 kg) force (like lifting coal from a mine) while walking at 2.5 miles (4 km) an hour. This calculates out as 550 foot-pounds (745 J) per second or 33,000 foot-pounds (44,740 J) per minute. This he arbitrarily defined, for all time, as 1 horsepower.

Today, machines have an amazing ability to convert the same amount of chemical energy into mechanical energy, creating movement and generating enormous amounts of horsepower in an extremely short period of time. The extreme example is the high-end drag racing car, which can blast through a quarter-mile race distance in less than four seconds at speeds over 300 miles per hour, or mph (480 kmph). It can generate enough power, 8,000 horsepower in fact, to reach a velocity of 100 mph (160 kmph) in just one second. In doing so, it pushes the driver back with a force five times that of gravity. To keep from achieving orbital velocity, the car has airfoils that push down on the wheels and keep them on the track.

How does it do all this? First, the fuel—that’s the chemical energy—is not your 87-octane Sunoco regular, but a special brand of nitromethane that burns with an incredible kick (you probably don’t want to light a match around it). The basic structure and function of the engine is the same as the Volvo’s (pistons and all that), but in the dragster, everything is bigger. It has twice the displacement of the 1992 model. And all sorts of other modifications are present, all designed to instantaneously squeeze enormous amounts of power in just a few seconds’ time. An air pump sucks oxygen in at a rapid rate to speed the burning of the fuel. There are also impressive sounding things like radical cam profiles, programmable ignition systems, and high compression ratios.

What about animals? This is a bit more difficult to address. To start with, how would a biologist studying this question convince an animal to run at top speed? And how could you be sure it was really running at top velocity? You would certainly argue, too, that the whole issue of maximal speed must be put into the context of how long the speed can be maintained. But having said all that, we know that certain mammals are speedsters, such as cheetahs and gazelles, who can approach running speeds of 70 mph (113 kmph). It’s said that a cheetah can accelerate more rapidly than a Ferrari and can reach stride lengths up to 25 feet (8 m). Not quite like on the drag racing track, but still amazingly fast.

In proportion to size, however, lowly insects are the fastest animals on the planet. The speed title goes to the puritan tiger beetle, which can scoot after prey at a meter (that’s equal to 80 body lengths) in a single second. These guys run so fast, in fact, that their eyes can’t keep up, and they end up losing sight of their lunch. The cockroach is a close runner-up, generating speeds up to 50 body lengths per second, which is equivalent to a human sprinter reaching 200 mph (320 kmph) or finishing a 100-yard dash in less than a second.

What about human athletes? They’re machines, just like the drag racing car. When they exercise, they burn fuel with oxygen to convert chemical energy into muscular activity, creating power. Some aspect of power production is important for most sports. For the wrestler, it’s the ability to drive a resisting opponent to the mat. For the road cyclist, it’s a question of how long a certain level of power can be sustained over a particular distance. This chapter focuses on events that demand the all-out peak performance of that motor machinery. When putting their bodies into motion, what’s the maximal power that humans can generate over time? The answer, as of August 17, 2009, is one which will drive an 86-kilogram man down a 100-meter track in 0:09.58. About 10 meters per second. That’s what Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt did to set the world record at the Berlin world championships, identifying him as the world’s fastest man ever. (Afterward, I headed down to the high school track and, ignoring my wife’s snickering, tried it for myself. My time, obviously impeded by a bit of headwind, was 0:26.28.)

How much horsepower did Usain achieve? Professor Vladimir Zatsiorsky, who is a biomechanist at Penn State, informs me that you can’t tell. You aren’t able to actually calculate horsepower production during sprinting since vectors of power production (directions of body movement) occur in multiple directions (vertical, horizontal, lateral), the contributions of elastic recoil can’t be accurately quantified, and energy transfer occurs between individual body segments. Moreover, the magnitude of the leg muscles’ power production in propelling the body toward the finish line depends on the portion of the race. Much more is required in the acceleration phase, although segment energy transfer and elastic recoil largely account for propulsion once a steady speed has been attained.

But how did Usain do this? What combination of physiological, biomechanical, and psychological factors makes his machine so incredibly unique? He and I use the same fuel (unless, of course, his future drug testing finds evidence of nitromethane). We both work with arms and legs. What special features give him the ability to generate that much power? How can his central pattern generator rev up with so much speed? This chapter explores the answers.

When Usain Bolt lined up at the start in Berlin, he had just one goal in mind—to maximize his power output for a very short time. He didn’t care much about submaximal metabolic efficiency, glycogen stores, or oxygen delivery. Looking down the track from the starting blocks, he simply wanted to cover that 100 meters with the motor machinery going full blast.

In sprinting, then, the limits of muscular capacity to produce force might be expected to play a more pure role in defining performance than in distance events. That raises a whole new set of questions. Just how fast can the central pattern generator go? Since it never seems to actually come off the tracks, is there a brain governor involved here that dictates an upper limit of oscillator turnover during sprinting in the name of runner safety? How important is the tempo of stride frequency to sprinting performance versus muscular force production (stride length)? What happens if you cognitively change one or the other? What are the effects of training?

To start with, does body size have anything to do with it? If you’re bigger, can you go faster? An interesting proposal was published in 1950 by the eminent English physiologist A.V. Hill, who concluded that any two animals that were proportionally similar in body shape would have the same top running speed, regardless of their weight. That is, a mouse should have a top running speed similar to that of a bear. The reasoning was that the mouse would have to take ten strides for every one of the bear’s, but those strides would be ten times quicker than the larger animal’s. Therefore, they’d cross the finish line together.

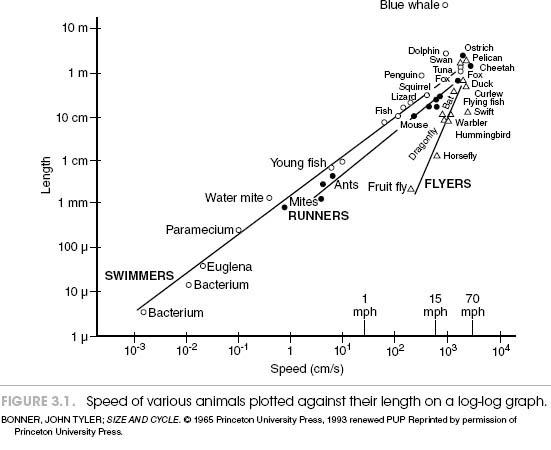

Well, that hypothetical reasoning might be based on sound mechanical ideas, but it doesn’t seem to jibe with our common expectations. The biologist John Tyler Bonner didn’t think so, either. He plotted the running speeds of animals ranging in size from bacterium to blue whales (this included results of a race created by a colleague between different types of mites) against body length. Not surprisingly, this approach showed that, in general, bigger animals are faster. Peak velocity of locomotion is directly related to animal size.

However, if you focus just on mammals, a somewhat different picture emerges. Look at the graph in figure 3.1, which plots the peak running velocity of these larger animals against the logarithm of body mass.2 There’s not much of a relationship to be seen. It would appear, then, that top running speed among mammals relates primarily to specific adaptations that equip them for high running velocity.

Note, too, that the human sprinter does not stack up very well against his fellow mammalian athletes. Although Usain Bolt can reach a top speed of about 30 mph (48 kmph) briefly during a 100-meter sprint, a pronghorn antelope can sustain 40 mph (65 kmph) for at least 20 minutes. A greyhound can sprint 100 meters in 5.33 seconds, beating Usain’s 9.58. The 200-meter sprint record for a thoroughbred race horse is 11.49 seconds. For a human being, it’s 19.19. Indeed, all sorts of animals are faster than humans, even the household cat, who can achieve speeds of 30 mph.3

If you want to propel yourself as fast as possible down a 100-meter track, you can only do it in certain ways. For starters, there are two basic means—you can increase the frequency of your stride or you can push off harder to lengthen each stride. Your top speed would be governed, then, by how fast you can crank up the CPG and by how much force you can apply to joint extension (in this case, mainly at the hip and ankle).

Beyond this, however, things get more complicated. For example, you can achieve a greater stride frequency by either repositioning your legs more rapidly or by limiting the time that your foot is in contact with the ground. Besides applying force, stride distance can be lengthened with elastic recoil forces. The speed of forward propulsion—the direction you want to go—can be altered by applying different horizontal and vertical vectors of force. A number of extrinsic factors can potentially affect sprint performance, such as terrain, shoes, weather, motivation, and wind resistance.

Let’s start this analysis of time as it affects sprinting performance by simply observing what happens to runners when they perform a short all-out sprint. Average sports fans who are sitting in front of the television watching a 100-meter sprint see a frantic blur of windmilling legs just after the crack of the starter’s gun. Just when they have figured out who’s leading, the runners burst across the finish line, and it’s all over. If they play the race back in slow motion, however, this event of about 10 seconds can be broken down into distinct phases. First is the starting block phase, which is the time it takes to leave the blocks. The time of progressive increase in speed, or the acceleration phase, comes next. This takes up the first 30 to 40 meters of a 100-meter event. This is followed by a period of constant top speed and a late phase of deceleration just before the finish line is crossed. When Usain Bolt won the 100-meter Olympic gold medal in Beijing, for example, his split times broken down into 20-meter segments were typical of this pattern (figure 3.2).

As the sprinter’s velocity changes during a 100-meter event, then, we can identify a time-velocity curve like this. Since the relative contributions of stride frequency and force production for stride length may differ for each phase, we can examine the running dynamics for each portion of the race.

Obviously, the less time spent getting out of the starting blocks at the sound of the gun, the better. This should be particularly true in sprints of short duration, like the 100-meter, where hundredths of a second may separate the winner from the runner-up. Reports have indicated that sprinters’ reaction times are not related to their finish times. And there have certainly been world-champion sprinters who did not start strongly. But in races this brief, it doesn’t often pay to have a sluggish start. So, sprinters work hard to minimize their time getting out of the blocks.

When researchers study simple reaction times, like how long it takes to push a button in response to a light signal, the value is usually about 0.235 seconds. The time is greater if the responsive act is complex or if some decision making is involved. Simple reaction times in trained sprinters seem to be much shorter. A group of French investigators found that the average time to press a button in response to an auditory stimulus was nearly three times quicker for sprinters than for nonathletes (0.128 compared to 0.352 milliseconds, respectively), while physical education students had intermittent values.4

Interestingly, then, sprinters’ reaction time (from the firing of the starter’s gun to leg push-off) is generally very short. Reaction times at the start of a 100-meter sprint are shorter for elite runners than for those with less experience. When defined as the time between when the gun is fired and when 10 kilograms of force are applied to the blocks, 100-meter sprinters typically have about a reaction time of 0.15 seconds.

The issue bears importance, since track-and-field organizations have defined a start less than 0.1 seconds after the gun as a false start. They level out punishment—disqualification—based on this criterion. This assumes that any time lag less than 0.1 seconds is incompatible with sprinters’ physiological reaction time. Therefore, their start would have preceded the gun.

Alexander Brown and colleagues at the University of Alberta analyzed starts for 100-meter events at both the 1996 and 2004 Olympic Games and found a relationship between reaction times and lane assignment. In these events, the starter fired the gun from a position inside the track and adjacent to lane 1. The signal and the voice commands of the starter were transmitted through loudspeakers that were placed behind each sprinter. This measure was to avoid any possible differential in start detection that might be caused by a delay of direct sound transmission. (That is, the sprinter in lane 1 would hear it first.) Brown and colleagues found that even with this system in place, the average reaction times of runners starting farther away from lane 1 were generally slower. The average reaction time in lane 1 was 0.160 seconds. For the other lanes, it ranged from 0.171 to 0.185 seconds. Out in lane 7, the mean reaction time was 0.185 seconds.

Investigators suggested that the sprinters starting closer to the starter had faster reaction times due to the greater volume and startle effect of the gun. (This doesn’t seem out of the question, since the bang can reach an intensity of 180 decibels.) They pointed out that “the difference in mean reaction time for runners in lane 1 compared to all other lanes was not trivial, given the fact that first and second places in the men’s 100-meter sprint final in 2004 were separated by only 10 milliseconds.”5

After the start, it may take the 100-meter sprinter as long as half the event just to get up to speed. It takes this long to overcome a number of forces that are acting to oppose the sprinter’s forward motion, including joint friction, muscle viscosity, gravity, and air resistance. It’s a very expensive start in terms of energy, too, since accelerating costs much more than maintaining a constant pace. Both the tempo of the CPG and the force directed per stride increase. That is, increases in both stride frequency and stride length contribute to the quickening of pace.

There is, of course, no way to get around this slower acceleration phase, although training may reduce its duration. The fixed contribution of time required to accelerate accounts for the interesting observation that a world-class sprinter can run a 200-meter event in less than twice the time it takes to finish a 100-meter race. For example, Bolt’s Olympic record times in the 100-meter and 200-meter events were 0:09.69 and 0:19.30, respectively.

During the middle portion of the sprint, most runners reach and maintain a peak velocity. Studies of the athletes running at various speeds have been performed to determine the relative contributions of stride frequency and length to velocity during this portion of the race. At relatively slow speeds (below 7 meters per second, or m/s), both stride rate and stride length increase in a linear fashion with rise in velocity. Increases in stride length are, as expected, accompanied by parallel rise in production of muscle force. Above this speed, however, stride rate increases more for a given increase in velocity. To achieve high speeds (as much as 12 m/s), runners typically rely mainly on heightening the tempo of the CPG, increasing the rate of leg turnover. Top stride frequencies during this phase for highly talented sprinters are usually 4.1 to 4.7 steps per minute (or hertz, Hz) but can reach as high as 5 Hz (300 steps per minute), which is equivalent to 150 full strides. So, we can be immediately suspicious that factors that limit the top tempo of the CPG might be critical for maximizing sprinting performance.

The stride rate during sprinting competition is the same for both men and women. Here, we have at least some mechanistic insight: Sex-related factors (such as sex hormones) do not affect the top firing rate of the CPG. On the average, elite male sprinters have faster sprinting times than their female counterparts by about 7%. This has been attributed to their longer stride length and their ability to generate greater ground reaction forces.

Men’s longer stride length is at least partially related to morphological differences, since the correlation between maximal stride length, body height, and leg length is generally high (with a correlation coefficient r = 0.60 to 0.70) among groups of both male and female sprinters. When measured in the laboratory with a 30-second, all-out Wingate cycling test, power is greater in males. This finding is explained by greater leg-muscle mass. That is, peak power adjusted for lean leg-muscle mass is equal in men and women. But, in one study, this couldn’t be verified with sprinting. The investigators examined body composition and 30-meter sprinting times in 123 men and 32 women. (It should be noted that the subjects were drafted from college physical education classes. They were not trained sprinters.) Mean sprinting times were 4.4 ± 0.2 seconds and 5.0 ± 0.2 seconds for the males and females, respectively. Finish time for the 30-meter sprint adjusted for lean-muscle mass of the lower extremities was actually lower for the men than for the women.6

Suffice it to say that overall faster sprinting times for men than for women may not be explained simply by differences in body dimension or even composition (leg-muscle mass). Other factors, including elastic recoil (women are more flexible), fiber length, velocity of muscle contraction, and anatomy of muscle fibers (angle of attachment) may be involved as well.

It is probable that the power production during the constant velocity phase of a short sprint (50 or 100 meters) must be close to the peak power that one can generate in the laboratory on a 30-second all-out Wingate cycling test, in which subjects are told to pedal as hard as they can. In such a test, power rapidly and progressively declines after about 5 seconds. It has generally been considered that the best sprinters can maintain a maximal effort for a similar period of about 5 to 6 seconds.

Runners’ speed slows near the end of a sprint, with loss of velocity from peak value of as much as 9% in a 100-meter event. The cause of this retardation has not been clearly defined. However, the toxic effect of accumulating lactic acid (a by-product of anaerobic metabolism) on skeletal muscle function has always been considered an important determinant. When velocity falls off while approaching the finish, a fall in stride frequency is usually responsible. Stride length may actually increase slightly. Coaches generally consider the most successful sprinters as those who slow down the least at the end, not those who start faster.

Performance determinants for the sprint can then be linked to each of these stages. Finish times can be influenced by reaction time (quicker times off the blocks), speed acquisition (shortening the acceleration phase), reaching and maintaining a maximal speed (the constant velocity portion), and minimizing loss of velocity when approaching the finish. Training strategies have been focused on each of these elements.

Steven Headley came to Springfield College equipped with some Caribbean genes that help him run fast. Very fast. As in 6.24 seconds in the indoor 55-meter dash or 10.51 seconds for the 100 meters outdoors. Both results are good enough to make him two-time NCAA Division III national champion in 2008-2009. (He did, in fact, pick the right parents. In Barbados, his mother was a sprinter, his father a first-class cricketer.)

Steven and I sat in the campus library one day amid a crowd of bleary-eyed students cramming for finals, chatting quietly about what it takes to be a champion sprinter.

Headley: When people watch a 100-meter race, they think everybody is just sprinting the whole time. But it’s a lot more complicated than that. You can’t run all out for more than about 4 or 5 seconds. That’s less than half the race. The guy who wins is usually the one who can sustain that top pace for the longest time, at the highest velocity.

After that, everybody slows down. At the finish line, it looks like some of the runners are putting on a burst of speed, surging past the others. But that’s not it. What’s really happening is those runners looking strong at the finish are actually not slowing down as much as the others. I really don’t know what causes me to slow at the finish. Sometimes I’m not even aware of it.

So, you really don’t want to accelerate up to top sprint speed too quickly at the beginning. If you do that, you won’t be able to sustain your maximum speed as long, and you’ll slow down sooner at the end. You don’t want to be sprinting until 50 to 60 meters into a 100-meter race. Also, a fast takeoff from the blocks is good, but if you can’t do that, it might not be a tragedy. One hundred meters is a long way. You can make up the time later. In shorter sprints (like the 55 meters indoors), of course, everything I’ve just said isn’t quite so true. There’s not much time to waste getting up to speed!

Rowland: Speaking of time, does it flow differently in your mind during, say, a 100-meter sprint?

Headley: It sure does. Ten seconds. That doesn’t sound like a long time. But when I stand at the blocks and stare down at the finish, it looks like a long distance away. And it sure feels like it takes a long time to get there. Time seems to get extended. But that doesn’t matter. I’ve got to be concentrating like mad the whole race. The mechanics have to be correct, the arms have to be pumping right, the body stable, the energy being sent down to my legs, keeping them low at the start. Just the tiniest mistake in all of this can cost you a good time, or even a win.

Of course, that kind of concentration is important in all sports, but with the sprints, it’s a bit different. You have to be focusing just on what you’re doing the whole time. You can’t do anything about how your opponents are racing. It’s not like football or tennis or almost every other sport in which you can try to out-maneuver or outsmart somebody else. In sprinting, it’s just you.

Rowland: Does that mean that you don’t think about the other sprinters as you head down the track?

Headley: Well, if you’re up against somebody who just nipped you at the tape last year, you can’t help being aware of him a little. But you’d never turn to look at him!

So, what’s more important to sprinters’ performance? Is it how quickly they can move their legs (stride frequency)? How much force they can generate on leg push-off (stride length)? How can they best spend those 10 seconds that will get them to the finish lines faster? Training strategies hinge on the answers.

Not surprisingly, like most questions about the limits of physiological function, the answer is not altogether clear. Alas, the whole matter is once again much more complicated than we might have hoped. Consequently, researchers are lining up on the side of stride frequency, stride length, or both as being most critical to sprinting performance.

Just to start with, stride frequency and stride length can be reciprocal. That is, if you increase your rate of striding but do not provide a parallel rise in muscle contractile force to lengthen your stride, the length of each stride will shorten. And vice versa. If this occurs, increasing either stride frequency or stride length will not affect your overall running velocity. And if you’re coaching your sprinters to work on improving one or the other, all their work will be for naught.

Then there is the fact that in providing an isolated increase in stride frequency (without an increase in stride length), the requirements for force production per step rises. That’s because as stride rate increases, the duration of the support phase (when the foot is in contact with the ground) progressively shortens. Since the amount of force required to propel body mass stays constant, a greater rate of force over time is required for each step. So, it’s not just the speed of leg turnover that increases as stride frequency rises, but also the rate of muscle force produced against the ground. Thus, as the rate of the CPG clock accelerates, the nervous system must transmit messages to the leg muscles to increase force as well, even if it is simply the stride frequency that is altered. It also follows that the runner is obliged to increase the strength of leg muscle contraction to effect both a rise in stride frequency and longer stride length.

In a particularly illuminating study, Joseph Hunter and his colleagues in New Zealand studied the mechanics of athletes who performed three maximal 25-meter sprints on a synthetic track that actually passed right through the middle of their laboratory. Sprinting velocities ranged from 7.44 to 8.80 meters per second. When analyzing the entire group of 36 subjects, a wide variety of ratios of stride frequency to stride length was found. The subjects with greater stride length had the highest velocities.

So, that means that stride length is more important than generating stride frequency when performing short sprints, right? Not so fast. When the authors examined stride frequency, stride length, and velocity within the three trials in each of the subjects, the results were different. In fact, the fastest trial times were related to the subjects’ highest stride frequencies. The times bore no relationship to stride length. (This is consistent with research findings indicating that over the course of a competitive season, runners accomplish their best sprinting times with a higher stride frequency. Stride length doesn’t change much.)

So, Hunter and coworkers found that the same runners used changes in stride frequency to effect changes in speed, while comparisons between runners indicated that alterations in stride frequency were more important. It seems difficult to reconcile these conflicting findings. The authors offered the possibility (which they admitted requires further examination) that “achievement of a greater sprint velocity via a longer step requires long-term development of strength and power, whereas step rate may be a more decisive factor in the short term.”7

Based on these data, it is difficult to offer a firm recommendation regarding the relative merits of optimizing either stride length or stride frequency in sprinting training regimens. The data supporting a contributing role of muscle strength and rate of force production to sprinting performance, on the other hand, are quite convincing. As the preceding information shows, such factors may have a determining role in increasing both rate of leg turnover and length of stride during sprinting performance.

Cross-sectional research studies have verified the importance of a number of variables for muscle function. For example, significant correlations with sprinting performance have been reported for explosive strength (as indicated by height of vertical jump), strength on squat lifts, drop jumps, force production on a platform, and measures of both isometric and isokinetic strength. Findings in such studies need to take in account the muscle groups tested, since the contribution of specific muscles to forward propulsion varies in the different phases of the sprint.

A.I. Bissas and K. Havendeditis found that the ability to rapidly generate muscular force was closely related to 35-meter sprinting performance (correlation coefficient of r = −0.73). They found that the time required to reach 60% of a maximum voluntary contraction during strength testing in the laboratory accounted for 35% of the differences in sprinting times.

Important in this discussion, too, is a consideration of type of muscle fiber. Sprinters tend to possess a higher proportion of what are called fast-twitch, or Type II, fibers in their leg muscles than the rest of us do. These fibers are specialists in facilitating short bursts of high-intensity activities by their rapid contraction times and use of anaerobic metabolism. The calf (gastrocnemius) muscle of nonathletes is made up of about 50% fast-twitch fibers. The same muscle in a typical elite sprinter has about 75%. As expected, studies indicate a close relationship between sprinting performance and percentage of Type II fibers in the muscles of the lower extremities. Your proportion of such fibers can only be blamed on your parents, though, since muscle-fiber composition is genetically based and is probably fixed at birth.

If fiber type of skeletal muscles serves as a major determinant of how fast one can run 100 meters, we would expect sprinting performance to be largely inherited. Claude Bouchard and Bob Malina reviewed the research studies addressing this question and concluded that a considerable variability exists in the degree of genetic contribution to running performance in short dashes. This included reports of heritabilities (here, a value of 1.0 indicates a trait that is entirely genetic) of 0.83 for 20 meters, 0.62 and 0.81 for 30 meters, and 0.45, 0.72, 0.80, and 0.91 for 60 meters. You might conclude, though, that these values are pretty high and would therefore support the idea that muscle fiber type plays an important role in sprinting performance (and also that this portion of your sprinting skill is already fixed before you even show up for track tryouts).

The elasticity of muscles and their connecting tendons provides a spring effect that allows the sprinter to bounce faster down the track. The exact contribution of this elastic effect to running velocity is difficult to pin down, but it is considered to be substantial. Writing in the Journal of Physiology (217: 709-721), G. Cavanga and colleagues found that muscle contractile function of the legs increased in parallel with running velocity up to speeds of 5 meters per second. They suggested that elasticity of the legs was largely responsible for further increases in their subjects’ speed up to a maximum of 9.4 meters per second.

Some interesting issues have been addressed regarding external influences on sprinting performance. For example, does the type of track surface affect sprinting times? If your high school decides to invest large sums of tax dollars in replacing the old cinder track with a synthetic rubberized surface, will the record you set for the 100-meter dash in 1970 fall? Maybe or maybe not. The issue is a complicated one. Synthetic rubberized tracks are more compliant—spongier—than the old dirt and cinder tracks. That might reduce the risk of injuries. However, if a track is too soft, it takes longer for your legs to rebound, and your sprinting times will be slower. On the other hand, if a track is hard, like concrete, there is no spring effect to propel you forward. Thus, a particular track compliance—not too hard, not too soft—will be just right for optimizing racing speed.

In 1977, Harvard University was in the process of building a 220-yard indoor running track with a wooden base and synthetic covering. They sent researchers Thomas McMahon and Peter Greene down to the gait analysis laboratory at Children’s Hospital in Boston to come up with some mathematical models of running mechanics that would enable them to calculate the right degree of track compliance to be tuned to its runners. Their calculations turned out to be spot-on. In competition that year, the average best time of the Harvard runners was 2% greater than the year before. Other schools followed suit with similar improvements. Moreover, running injuries on the new tracks were said to be reduced by 50%. So, synthetic tracks may offer improved performance by augmenting energy rebound (and thus enhancing energy economy) and decreasing injury rate. (Of course, opponents would accrue the same advantages.)

However, the distance of the race might have an effect on these findings. Researchers at the German Sport University in Cologne found no significant differences in 60-yard sprinting times when the run was performed on hard, soft, or springy track surfaces. They concluded that the differences between track surfaces are sufficiently small as to have little impact on sprinting times.8

Steven Headley, though, has no doubt from his personal experience about the faster times he attains on newer high-tech synthetic tracks. “Improvements in sprint times can be due in part to better training,” he says, “but there’s no question that changes in track surfaces have a lot do with it. If I run 55 meters in 6.3 seconds at Boston University and then come home and do the same time at the Springfield track, people know that I really had a better day in Boston because the track there is slower.”

What happens when you sprint around the curve of an oval track compared to running down a straightaway? Your velocity around the curve will fall off, with the extent of the decrease related to the sharpness of the curve. Researchers have found that in 200-meter competitions, runners are up to 0.4 seconds slower on a curve compared to a straight portion of the track. The amount of the delay is directly related to the curvature of the track. The greater the curvature, the slower the time. Thus, the runner in an outside lane has a potential advantage over competitors on the inside. One study compared sprinting velocities when subjects were running down a straight track with performances on circular tracks with radii of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 meters. Velocity progressively fell as the sharpness of the turn increased. It has traditionally been supposed that this occurs because on a curve, an application of a lateral ground-reaction force causes a decrease in peak vertical ground-reaction force, which is really the direction you want to go (figure 3.3). That is, if you have to turn, some of the force of your leg extension must be used for this purpose, which steals force away from forward propulsion.

Findings in this study, however, support another possibility. The authors found that you may slow as you round a curve because smaller peak forces are generated by the inside leg than by the outside one. This all has to do with complicated concepts of centripetal force, rotational velocities, and biomechanical restraints. Indoors, tracks can be designed with banked turns to reduce this effect, but this technique usually only works for a specific speed (for example, quarter-mile, or half-kilometer, competitions).

The authors noted that quadrupeds (four-legged animals) are able to decouple such constraints, and so they handle curves better. More than one researcher, it seems, has committed professional time to actually documenting that mice and dogs can round a curve at relatively greater speeds than sprinting humans.

The starter’s gun fires, and they’re off the blocks! For the first 30 meters, the CPG system of each runner revs up, driving the frenzied running tempo at increasing rates. At that point, it plateaus off, and then remains pretty stable to the 100-meter finish line. There seems to be a ceiling above which the CPG pacer and corresponding stride frequency for a particular athlete cannot go. Why can’t it go faster? What factor or factors limit leg turnover rate? Some of the observations outlined above would have us believe that one’s ability to generate stride frequency might play a serious role defining sprinting abilities. If so, coaches and athletes might well benefit from an understanding of just what creates the apparent limits to stride frequency during these events. In trying to do so, we are clearly in terra incognita here—the descriptive or experimental research is extremely scant. But let’s consider some ideas.

Harkening back to our CPG model from the previous chapter, we can consider components of this automatic oscillatory system, driven by internal clocks, that generates the rhythm, tempo, and force of muscular activity during the dash to the finish tape. Viewed in a simplistic way, the basic oscillator resides at the level of the spinal cord, the force and tempo are controlled from the lower brain centers, and, in humans, cognitive and subconscious cerebral input provides information as well. Where in this system might we identify factors that would define the upper limits of its cycling rate?

You will remember that the principal actor in the CPG is the spontaneous, automatic, regular-like-clockwork electrical firing of single nerve cells within the central nervous system. The automaticity of these neurons occurs from movement of electrolytes (sodium, potassium, calcium) across the cell membrane. Although, like the sinus node pacemaker of the heart, these neurons possess an intrinsic firing rate, the rate of spontaneous firing (and therefore the rate of impulse generation) is clearly influenced by a number of external factors. In the portion of the CPG in the spinal cord, the rate of firing is dictated by higher brain centers (much as the sympathetic nervous system speeds up the spontaneously firing of the sinus node of the heart when you’re frightened). What determines the maximal firing speed of these pacemaker neurons is not known, but obviously there must exist upper physical-chemical limits to rates of electrolyte movement across membranes (intrinsic control) and the commands of brain governors that influence pacemaker firing rate (extrinsic control).

As noted previously, biopsy data indicate that sprinters possess a greater percentage of fast-twitch Type II fibers than distance runners (who have more Type I, or slow-twitch fibers) or nonathletes do. Type II fibers are particular adept at the kind of work required for sprinting performance. They possess a greater metabolic capacity for anaerobic metabolism, generate high muscular force over brief periods, and—pertinent to this discussion—they can contract at a velocity that is twice as fast as that of slow-twitch fibers. For example, the twitch contraction times for a cat’s calf muscle are 75 and 40 milliseconds in slow-and fast-twitch fibers, respectively.

The greater the percentage of Type II fibers, the better the sprinting performance. It can readily be suggested that the upper limits of stride frequency could be defined by one’s percentage of fast-twitch fibers in the critical leg muscles (the more fast contractors you’ve got, the faster your legs can cycle). In this case, the limiting factor for stride frequency during the constant speed phase of a sprint would be the number of fast-twitch fibers and the ability of individual Type II muscle fibers to speed up their contractions. The nature of that mechanism might be sought in an understanding of why Type II fibers can contract faster than Type I.

That makes for a nice segue to a consideration of the possible role of limitations in nerve conduction velocity for defining maximal CPG tempo. The speed at which electrical impulses are transmitted in neurons is quicker in those supplying Type II muscle fibers than Type I. That’s because the axons of Type II motor neurons are larger. (We know this from studies of neurons in the giant squid, whose enormous axons—up to 1,000 times thicker than yours and mine—provide it with lightning-quick impulses that generate explosive contraction of its mantle musculature for propulsion. Consider this the next time you’re enjoying a pile of fried calamari.)

As expected, then, sprinters have greater velocities of nerve conduction than athletes in other sports. Can this be improved with training? Who knows? Studies have described increases, decreases, and no change in axon diameter of motor nerves following training.

Chapter 1 discusses the concept that the brain, acting subconsciously, might limit distance-running effort to protect an athlete from the potential risks of overexertion (heat stroke, coronary insufficiency, muscle tetany). In this model, the central nervous system acts to create those intolerable sensations of fatigue that make you stop with your well-being in mind. Could this same self-appointed governor limit stride frequency and velocity during sprinting as well?

St. Clair Gibson and his colleagues thought this could be the case. While noting that no direct evidence for this exists, they felt that certain observations supporting the role of a CNS governor during maximal muscle contractions might apply to sprinting activity as well. This makes some sense, since we’ve seen that force production (both its extent and rapidity) also contribute to sprinting performance.

For example, if you contract your abductor pollucis longus (thumb) muscle as hard as you can, force output steadily declines over time. After 60 seconds, it will fall to about one-third of its original value. The same pattern is mimicked if you simply decrease an externally applied electrical stimulation to the same muscle by a third. This suggests that human motor units do the same thing. That is, they reduce their firing rates during sustained maximal muscular contractions. To St. Clair Gibson and his colleagues, this suggested that “the decrease in firing frequency may therefore be a centrally controlled mechanism to maintain force output while protecting fatiguing fibers from damage incurred by ongoing muscle contraction and ATP and phosphocreatine depletion.”

They interpreted the progressive decline in power typically observed when a runner completes a series of sprints, one after the other, in the same way. The pattern of performance falloff in repeated sprints is, in fact, very similar to that observed in the model of force production over time in the single sustained maximal contraction of the thumb muscle described previously. Such decreases have traditionally been attributed to local metabolic changes, but St. Clair Gibson and colleagues contended that the decline in performance in repeated sprints is not necessarily tightly related to these factors. They proposed that the brain may sense that repeated sprinting with fatigued muscles might cause damage. In response, it may deregulate central command to limit force production and sprinting performance on subsequent repetitions.9

If such a governor did exist for stride frequency during sprinting, what adverse outcomes would it be protecting us from? That is, what possible harm would we risk by pushing stride frequency beyond some certain apparent upper limit? The most obvious possibility would seem to be risk of musculoskeletal damage. Increasing stride frequency shortens time of foot contact. Since total force must be approximately constant for each foot strike, the peak force the foot applies to the ground can be expected to be directly related to stride frequency (assuming a stable stride length and ignoring other factors, such as change in force vectors and elastic recoil).

If velocity is constant, increasing stride frequency does nothing more than shorten stride length (one is the reciprocal of the other). As sprint speeds increase, though, we’ve seen that both stride length and stride frequency can contribute. There may be some upper limit, however, in which the stride distance can no longer be lengthened, or even maintained. In that case, increasing frequency would be of no value to the runner, since velocity would not be increased.

We can see that, for the most part, the essential factors contributing to top speed in the several seconds of sprinting time are reasonably well recognized. We know that the strength, explosiveness, and velocity of muscle contraction, flexibility (elastic recoil), and rate of leg turnover (stride frequency) are all important. It is recognized, too, that such factors may not contribute in the same way in the different phases of the sprint.

Particularly relevant are the findings of French researchers who looked at the contribution of leg strength and flexibility to velocity in each third of a 100-meter sprint in experienced runners. They showed that strength (as measured by half-squats with loaded barbells) was a predictor of total 100-meter time as well as performance in each of the three separate 30-meter phases. Explosive power, which was assessed by a countermovement jump, was also associated with both 100-meter time and with velocity in the first segment. A hopping test was connected to performance in the latter portion of the race. Those who had greatest leg stiffness increased their speed the most between the first and second phases, but slowed down more at the end.10

This study suggested that particular motor tests could be useful in identifying an individual sprinter’s strengths and weaknesses in the different portions of the sprint. Moreover, its implications for specific training strategies might be effective in improving performance in particular race segments.

The bottom line, then, is that appropriate training regimens are best designed with the idea of maximizing all components of sprinting fitness. Traditionally, this is what coaches have done. Standard methods of resistance training (particularly weighted squats or dead lifts) have been used to improve muscle strength. They are designed to avoid increasing muscle bulk or decreasing flexibility. Speed drills (that is, those that mimic race conditions) are deemed essential. Plyometric exercises are commonly employed, although it remains controversial whether jumping on or off boxes is really useful in optimizing sprinting times. Skipping, hopping, and quick-recovery high-knee running are designed to improve contraction velocity, flexibility, and strength.

What about stride frequency? The preceding discussion suggests the importance of leg turnover rate in sprinting performance, but also makes the observation that a ceiling of stride frequency during sprinting seems to exist (perhaps beneficially dictated by a CNS governor). Can the intrinsic clocks that dictate cyclical rhythms of leg muscle contraction be convinced to go faster? Should they be convinced to do so? Is it wise? (We’ve already mentioned some potential risks.) How might one go about increasing stride frequency during sprints?

At the least, we can respond to the last question. A number of training methods have been suggested to augment stride frequency. The easiest is simply running downhill at a very slight decline. You can perform sprints with the wind at your back. Certain devices will tow a runner. Coaches have advised caution when attempting to increase cadence with training, however. They warn that musculoskeletal injury and damage from falling can occur, particularly if the runner lacks trunk stability or good form. As to whether these methods really work to increase stride frequency and whether any such increases translate into improved performance does not seem to have been well documented. (Some reports have confirmed training-induced increases in stride frequency, albeit with a compensatory decrease in stride length.)

Indeed, this last comment appears to apply to the entire question of whether sprinting performance can be trained. We are accustomed to the concept that repeated, activity-specific exercise (training) triggers adaptive physical and physiological responses that translate into improved sport performance. The magnitude of such training responses in sprinting, though, has always been difficult to pin down. Considering variability of individual performance and the fact that the differences between being super and mediocre are in the range of tenths or even hundredths of a second, it is difficult to document training responses, much less to identify the training methods that might be the most effective. Indeed, a strong genetic influence on being quick, as manifested by an abundance of fast-twitch fibers in a runner’s leg muscles, leads many to suggest that a superior sprinting ability is largely handed down from the runner’s parents. It is not simply a result of intensive and extended training.

However, the old idea that great sprinters are born, not made, has gone by the wayside. Most coaches would agree that appropriate training regimens are critical for developing sprinting success. Given this, it is surprising that very few studies have been performed to see if gains from training techniques that are designed to enhance muscular strength, explosive strength, and velocity of contraction serve to actually improve sprinting performance. A group of Belgian investigators did demonstrate that nine weeks of high-velocity training (with plyometric exercises, jumping, and hopping) resulted in improved initial acceleration, greater maximal velocity, and better 100-meter times, as compared to a control group. The only effect of training with resistance exercise was an improved acceleration phase. No decrease in overall sprinting time was observed compared to the controls. Other studies have had mixed findings.11

Through the years—and particularly when the Olympic Games roll around—scientists have raised the question of the limits of running speed. Just how fast can human beings go? Since recorded history, winning sprint times have continued to improve, but is there a limit? What’s the very fastest that humans can propel themselves down a 100-meter straightaway? So, investigators plot world-record sprinting times against race competition dates, connect the dots, extrapolate to the future, and attempt to draw conclusions.

The issue is far from trivial. Indeed, it can be viewed from a variety of mathematical, physiological, sociological, and even philosophical perspectives. It has bearing on such weighty questions as sexual equality, ethics of genetic engineering, and the essence of what it means to be human. For this book considering time, it asks us to think about the maximal potential of a central pattern generator to drive a muscle motor against a few clicks of the clock.

Think about historical plaques for a moment. There’s one at the University of Chicago where the old football stadium once stood indicating the site of Enrico Fermi’s first achievement of a controlled nuclear chain reaction. There’s one at 74 rue du Cardinal-Lemoine in Paris, where Ernest Hemingway wrote A Moveable Feast in his upper-floor flat. And one in Lexington, where the “shot heard around the world” set off the American Revolution. But for an homage to sports and time, nothing is more moving, more stirring, than the plaque standing in Armory Square in Syracuse, New York, commemorating—what else?—the invention of the basketball shot clock.

The inscription reads:

This clock honors the rule that changed basketball and saved the National Basketball Association. The 24-second shot clock, which put an end to stalling tactics that were threatening the league, was used for the first time in an NBA scrimmage organized by Danny Biasone on August 10,1954 at Blodgett Vocational High School in Syracuse. In the first season with the clock, league scoring would rise by 13.6 points per game.

Reading on, you learn that coach Howard Hobson (Oregon State, Yale) first thought up the idea of the shot clock, but Emil Barboni and Leo Ferris were responsible for coming up with the 24 seconds. You had to get a shot off before it expired. It seems they took the number of seconds in a 48-minute game (2,880) and divided it by 120, the average number of shots taken in a game at that time. (In collegiate competition now, it’s 35 seconds for men and 30 seconds for women.)

Basketball fans over the age of 50 or 60 remember what the game was like before all this happened. A team would get ahead in the second half, and the four-corner offense would begin, a contest of keep-away in which the leading team would try to stall the game out to the end. It included lots of fouling, and was incredibly b-o-r-i-n-g. You’d see scores like the 19-18 win by the Fort Wayne Pistons over the Minneapolis Lakers in November of 1950. Well, with the advent of the shot clock, the game picked up pace, and, so they say, the NBA was saved.

For sports history buffs seeking a pilgrimage, I understand the original shot clock is located at Le Moyne College in Syracuse.

When Usain Bolt set his 100-meter records, he was dubbed the world’s fastest human. No doubt, that’s an electric statement—in the millions of years of human existence, no person has ever run that distance faster, and we were here to witness it. But what does this really mean in respect to the limits of what the human machine can do? What is it telling us about human potential? Let’s consider two perspectives—two very different concepts that would, in fact, seem to be polar opposites.

Idea 1. A world record of running performance time is a numerical indicator, a quantification of the functional limits of the human body. The sliding of actin-myosin filaments in response to electro-chemical stimulation can only occur so fast. There is a maximum rate, based on biophysical principles, at which neurons can repetitively fire in the brain, at which electrolytes can move across cell membranes in response to electrical gradients to permit nerve conduction, at which chemical energy can be converted into mechanical work. Laws of physics, of chemistry, of biology place a limit on how fast the human machine can go. This is objective reality. World sprinting records are set by extraordinarily rare individuals who can take these processes to the extreme.

Idea 2. Every human athletic performance, including the world record in the 100-meter sprint, is a second-best effort. There is always a reserve. Usain Bolt could have gone faster. We know this because at the finish line, he suffered no critical body damage—his heart, lungs, muscles, bones, and brains were all intact. Our bodies (read central governors) protect us from the true risks that would occur with a maximal performance. It does this by diminishing signals from the brain that lessen the force of muscle contraction and by overwhelming us with disagreeable sensations of fatigue that cause us to slow down or stop.

Humans are machines with functional limitations, yes, but they are apparatus with a safety governor. World-record sprinting times are set by people with the capacity to make the most of these limitations.

Solomon-like wisdom from the Great Conciliator. Maybe both ideas are valid.

When people have plotted winning Olympic times for the 100-meter sprint against dates, they show what looks like a straight line of improvement throughout the years. That is, they report a linear relationship between year and gold-medal times. In the last century, this has amounted to a full second of improvement in 100-meter sprinting times for men. When these findings are compared between men and women, things get interesting. The slope of the line, or the rate of improvement, is greater for females than for males. In fact, Andrew Tatum and his research group in the United Kingdom predicted the two lines would intersect in the year 2156. After that, based on their projections, women would run the 100 meters faster than men. “Only time will tell,” they conclude, “whether in the 66th Olympiad, the fastest human on the planet will be female.”12 (Whether this will actually occur, of course, no one knows. But, here’s a clue. Based on a similar analysis of marathon performance by sex, it was once predicted that women would outrun men in the marathon by the year 1998.)

Alan Nevill and Greg Whyte, another pair of British investigators, claimed such analysis suffered from methodological pitfalls. With polite restraint, they pointed out that the linear modeling of trace performance cannot be correct, since it implied no ultimate limit of sprinting times. Moreover, it led to the obvious conclusion that sprinting performances would eventually result in negative world-record times. That would mean that the sprinter would finish the 100 meters a certain time before the starter’s gun sounded.12

These authors suggested that, instead, performance records plotted as velocity versus date actually followed a flattened, S-shaped curve. By this analysis, they said, there are limits to sprint performance, represented as the asymptote of this curve. They thought, too, that the greater improvement in women’s records reflected the fact that the more recent participation by females placed them on the accelerated portion of the curve.

Thinking about this, it seems obvious that there must be a limit, an absolute time below which no human will ever be able to run 100 meters. Here’s the argument. Would you accept that a 100-meter record will never be less than, say, 4.0 seconds? Sure. Okay, how about 9.0 seconds? No, it’s not unreasonable that someday that barrier will be broken. The conclusion, then, is that somewhere between 4 and 9 seconds is a certain absolute limit that will never, ever be broken.

Having settled that an ultimate limit for the 100 meters exists doesn’t mean, though, that humans might not continue to improve 100-meter sprinting performance. If a runner has an accurate enough clock and the willingness to add decimal points, performance can continue to improve, even if an absolute lower limit exists. Let’s just say that no man or woman will ever run a 100-meter sprint in 8.0 seconds. But, in successive Olympic competitions, gold medal times could be 8.01, then 8.009, then 8.0009, ad infinitum.

None other than Andy Warhol made note of this. In his Philosophy, the artist talks about his musing when watching Olympic meets. “If somebody runs at 2.2, does that mean that people will next be able to do it at 2.1 and 2.0 and 1.9 and so on until they can do it in 0.0? So, at what point will they not break a record? Will they have to change the time or change the record?”13

Some have suggested that increases in sprinting record times reflect improvements in the biophysical properties of runners (for example, improvements in the capacity to generate energy by anaerobic metabolism). This could occur from factors such as improved training techniques or early identification of talent. Societal factors could also be involved. Giuseppi Lippi and colleagues have written that “economic advances and broader coverage of sports by the media have contributed to enhance the base number of athletes, including those at higher levels. This has increased the chance that ‘extreme outliers’ will occur in a normal distribution of athletes, and may partly account for an improvement in records.”14

The Italian physiologist Piero Mognoni has emphasized the importance of training in accounting for improvement of world running records. He points out some interesting comparisons of human sprinters with race horses, whose capabilities are more related to selective breeding than to intensive training regimens. Over a distance of a mile (1.6 km), a race horse can gallop 2.47 times faster than a man can run, but horse-racing records are seldom broken. Over the past 20 years, 1-mile speed records have increased by 11.2% for humans, but only by 2.8% for horses. The conclusion? “An inadequate improvement in training techniques seems the easiest explanation of the history of equine records.”15

Other external influences have clearly contributed to trends of improvement in record-breaking sprinting performance. It has been considered that the switch from manual to electric timing reduced times in the 100-meter event by 0.24 seconds and in the 200 meters by 0.14 seconds. Also, before 1930, sprinting times were recorded to the nearest 0.2 seconds, to the nearest 0.1 seconds from 1930 to 1964, and to .01 seconds after that. Changes in nutritional strategies, track surfaces, and training opportunities have been influential. Sadly, we must also include on this list the use of illegal (as well as legal) performance enhancement substances.

An undercurrent of sentiment in all such discussions holds that, according to Lippi and colleagues, “future limits to athletic performance will be determined less and less by the innate physiology of the athlete, and more and more by scientific and technological advances and by the still evolving judgment on where to draw the line between what is ‘natural’ and what is artificially enhanced.”14

Also, on the horizon are the approaching dark clouds of genetic selection and manipulation that will tax our ideas of the meaning of sports talent and performance as they touch all other aspects of human existence. We’re not there yet, but the number of genes identified as being associated with physical fitness and performance continues to grow each year. In 2008, Greek investigators reported that a piece of chromosomal material called the ACTN3 gene was more than twice as common in elite sprinters as in nonathletes. One could suspect that once this substance becomes covered by insurance, a million Usain Bolts could emerge.

Finally, we can use the example of Boston College football receiver Gerard Phelan to point out that firing the CPG up to warp speed is critical for sports other than sprinting. Phelan, football fans don’t need to be reminded, was on the receiving end of Doug Flutie’s miracle pass that beat Miami on that game’s unbelievable final play in 1984. Trailing 45-41 with a mere 28 seconds left, Flutie directed the Eagles to the Miami 48-yard line. There, with just six ticks left on the clock, time remained for one last desperation pass. Flutie dropped straight back, then scrambled to the right. With one second remaining, from his own 37-yard line, he sailed a pass that seemed to fly forever, over the outstretched hands of the Miami defenders in the end zone and—plop!—right into Phelan’s arms for the incredible touchdown and victory.

John Eric Goff is chair of the physics department at Lynchburg College, and he’s clearly taken great delight in figuring out the physics that explain how this magical moment took place. If you’re into heavy math, check out his analysis in Gold Medal Physics. The Science of Sports (Johns Hopkins Press, 2010). For the rest of us, here’s the summary.

From the snap of the ball, it took Flutie five seconds to release his pass, and the ball was in flight for around three seconds. So, Phelan had eight seconds to put himself into position to catch the ball in the end zone, 50 yards away. Dr. Goff estimates that the acceleration phase of this sprint (remember, wearing 15 pounds, or 7 kilograms, of equipment) lasted two seconds, and this carried him 10 yards. With his CPG now at full blast, Phelan maintained a constant velocity to cover the remaining 40-yard sprint in less than six seconds. (A possible deceleration at the end is unknown.) Now, at this point, when you and I would have collapsed in exhaustive agony, Phelan had to look alive and gather in the game-winning pass.

Flutie’s performance at the launching end, of course, was no less impressive. Just how did he heave a perfect spiral 62 yards to the exact right spot, into a headwind no less? Goff thinks that the angle of launch was about 38 degrees, with an ejection speed of at least 58 mph, enough to reach the end zone in three seconds. And, if the ball were not thrown in an aerodynamically perfect spiral, it would have encountered so much wind resistance that it never would have gotten there.

Some have considered this the greatest college football play of all time. We know, of course, that more accurately, it was just the synchronization of two highly efficient neuromuscular systems, their central pattern generators, and a pair of finely tuned intrinsic biological clocks.

1. He is not infrequently confused with Isaac Watts, the English clergyman who wrote the Christmas hymn “Joy to the World.” His history has nothing to do with steam engines and is a different tale altogether.

2. Read about animal speed versus body size in the following sources: Bonner, J.T. 2006. Why size matters. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. van Ingen, S., J.J. de Koning, and G. de Groot. 1994. “Optimization of sprinting performance in running, cycling, and speed skating.” Sports Medicine 17: 259-275.

3. After Usain Bolt set sprinting track records in the summer of 2009, his performance was analyzed against members of the animal kingdom in the following article: Stracher, Cameron. 2009. “Usain Bolt versus the house cat.” The Wall Street Journal, August 24.

4. Hamon, J.F., B. Seri B, and B. Camara. 1989. “Motor skill acquisition influences brain responsiveness in sprinters.” Activitas Nervosa Superior 31:1-6. A study of city bus and taxi drivers in downtown Belgrade also suggested that quick reaction times can be learned from repeated experience (such as sprint training). These drivers, whose occupations require rapid responses to sensory signals, were found in laboratory testing to have heightened sensitivity to visual stimuli. (Remember this the next time you’re trying to hail a taxi in a rainstorm in downtown Manhattan.)

5. A consideration of the effect of lane position on sprint reaction times can be found in this source: Brown, A.M. et al. 2008. “‘Go’ signal intensity influences the sprint start.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 40: 1142-114.

6. Perez-Gomez, J., G.V. Rodriguez, I. Ara et al. 2008. “Role of muscle mass on sprint performance: Gender differences.” European Journal of Applied Physiology 102: 685-694.

7. For further reading, see the following articles: Hoffman, K. 1971. “Stature, leg length, and stride frequency.” Track technology 43: 1463-1469. Hunter, J.P., R.N. Marshall, and J.P McNair. 2004. “Interaction of step length and step rate during sprint running.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 36: 261-271.

8. Read about track surfaces in the following articles: McMahon, T.A., and P.R. Greene. 1978. “Fast running tracks.” Science American 239: 148-63. Stafilidis, S., and A. Arampatzis. 2007. “Track compliance does not affect sprinting performance.” Journal of Sports Sciences 25: 1479-90.

9. St. Clair Gibson, A., M.I. Lambert, and T.D. Noakes. 2001. “Neural control of force output during maximal and submaximal exercise.” Sports Medicine 31: 637-650.

10. Bret, C., A. Rahmani, A.B. Dufour et al. 2002. “Leg strength and stiffness as ability factors in 100-meter sprint running.” Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 42: 274-81.

11. References for effects of motor fitness on sprinting performance: Delecluse, C. 1997. “Influence of strength training on sprint running performance.” Sports Medicine 24: 147-156. Dintman, G.B. 1964. “Effect of various training programs on running speeds.” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 35: 456-463. Wilson, G.J., R.U. Newton, A.J. Murphy et al. 1993. “The optimal training load for the development of dynamic performance.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 25: 1279-1286.

12. See the following articles: Nevill, A.M., and G. Whyte G. 2005. “Are there limits to running world records?” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 37: 1785-1788. Tatem, A.J., C.A. Guerra, P.M. Atkinson et al. 2004. “Momentous sprint at the 2156 Olympics?” Nature 431: 525. Whipp, B.J., and S.A. Ward. 1992. “Will women soon outrun men?” Nature 25: 355.

13. Warhol, Andy. 1975. The philosophy of Andy Warhol. From A to B and back again. Orlando, FL: Harcourt.

14. Lippi, G., G. Banfi, E.J. Favaloro et al. 2008. “Updates on improvement of human athletic performance: Focus on world records in athletics.” British Medical Bulletin 87: 7-15.

15. Mognoni, P., C. Lafortuna, G. Russo et al. 1982. “An analysis of world records in three types of locomotion.” European Journal of Applied Physiology 49: 287-299.

1. Specific training for different segments of the sprint—start, acceleration, top velocity, deceleration—with attention to technical aspects of each is critical for sprinting success.

2. Sprinting performance calls for optimizing the velocity and force of muscular contraction, as well as cranking up the central pattern generator to full speed (maximizing stride frequency).

3. In the past, such capabilities were considered mainly genetically based, and it was generally thought that few improvements could be attained by sprinting training. Currently, coaches feel that specific techniques to improve each of these determinants, including increasing the peak tempo of the CPG, can enhance sprinting times. There is, however, little scientific documentation of these gains.