I’ve seen the movie Giant maybe three times. So when I placed the phone call to Bob Malina down at his home in Texas, I saw the scene in my mind’s eye. Professor Malina was probably sipping lemonade out on the veranda of his sprawling ranch home. Before him were the sweeping vistas of the coastal plain, with seas of grass and cattle stretching horizon to horizon. Forests of oil derricks. Maybe Elizabeth Taylor. (No, I was later informed. The cattle ranch belongs to his mother-in-law, not Elizabeth Taylor. Oil wells are things of the past, and the local residents are trying to block a coal-fired power plant on the horizon.)

I had told Bob that I was writing this chapter on the development of athletic talent. About the time between early childhood and the early adulthood, when a training athlete’s ability to perform in sports steadily improves, a discrete window of opportunity exists for turning this rise into elite performance. The age of peak performance varies by sport and among individual athletes, yet every event presents a certain time deadline. After this time, even with continued training, performance heads south.

Many question how athletes should be trained within this time constraint. Most particularly, I was wondering about the controversial issue of if, how, and when sport training should be started with young children. Could I talk with him and get his ideas on this?

Bob was gracious enough to agree. This was a stroke of good fortune, for there probably is no one on the planet with greater expertise in the science of developing young athletes. Professor Malina has a double doctorate—one in anthropology (University of Wisconsin), the other in physical education (University of Pennsylvania). He spent much of his career at the University of Texas before moving on to Michigan State. His research has provided the details for how sport performance is related to growth and development in children. He has a teaching legacy, too. An impressive cadre of former students has achieved prominence in the scientific field of pediatric exercise.

Every time I meet up with Bob, I recall participating in a conference in Hong Kong with him a few years back. While touring the city, I made the error of treating Bob and his fellow colleague Colin Boreham to a quick cup of coffee at the Peninsula Club. My gaffe was rapidly disclosed when the check arrived bearing a demand for $35 U.S. Sadly, I could have easily avoided the error if I had noted the fleet of Rolls-Royce vehicles stationed in front of the hotel. (The astute reader will recall, in fact, that this exact scene is portrayed in the James Bond movie The Man With the Golden Gun.)

But I digress.

Rowland: Bob, this whole business of figuring out how to improve physical prowess on the athletic field in the 15 odd years that time permits is really a complicated one, isn’t it? Some exercise scientists have spent their whole professional lives trying to sort this out. At a basic level, they’ve sought to gain insights into just how our motor abilities can be improved. That has importance not only for understanding physiological principles, but also for taking care of people with all sorts of chronic diseases, like those in cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation programs, and for patients with neuromuscular disorders, such as cerebral palsy.

It’s within the world of sports, though, that the importance of success has become so crucial (dare I say exaggerated?) in contemporary society. Here, the question has gained critical importance. There’s the father who’s just fashioned a tennis ball to swing above the crib of his 6-month-old son, hoping for a head start in his son’s future entry into the Australian Open. There’s the head of the U.S. Olympic training center who needs to know how he can identify talented swimmers at an early age. The parents of a 10-year-old who just sank five shots in a row from the key in her last game can’t decide if they should let her travel with the AAU junior team or if they should enlist her in several different sports. And the director of a youth football league is up to his waist in anxious parents who don’t think his practice of matching competitors by age is appropriate.

Malina: It has to be realized that there are no simple answers to how athletic talent can or should be developed—not to mention predicted—within the time constraints of the first part of life. Many factors contribute to sport skill, many factors influence how these can be improved over time, and many factors affect how indicators of athletic performance at an early age might or might not predict later success in the competitive arena.

Rowland: But let’s see if we can tease out some of the answers, or at least talk about what researchers think about these things.

Malina: Okay.

Rowland: Because this is such a complex subject, maybe it would be best if we start at the very beginning and then build a story from there. Let’s look at figure 6.1.

Malina: I don’t see a figure 6.1.

Rowland: You’ll see it when the book is published. Trust me on this, Bob.

Malina: Okay.

Rowland: A good starting place is to state that during the growing years, physical performance steadily advances up until late adolescence, on the average, in just about every motor activity you can think of. Running a 50-meter dash, throwing or kicking a ball, lifting weights. They all improve with age. A 15-year-old boy can run a mile (1.6 km) almost twice as fast as a 6-year-old can. A 14-year-old girl can jump twice as high as she could 10 years earlier. At age 6, the average boy can throw a softball 12 meters, but he can fire it 50 meters at age 15. So, performance in basic athletic skills improves dramatically as children grow, even if they do nothing but sit in front of the television every day after school. That’s what we see in figure 6.1. The horizontal axis is age, the vertical axis is performance on a motor task. We recognize this as a basic biological trend on which we can base the rest of our discussion.

Malina: You can see that this is going to be a major challenge for those who study the effects of athletic training on children. They’ll have to be able to separate out any effect of programs of skill development and training from those that accompany the normal growth, maturation, and developmental improvements that occur during childhood and adolescence.

Rowland: What factors are most responsible for this natural improvement in motor abilities as children grow?

Malina: This increase in athletic prowess is largely due to increase in body dimensions and neuromuscular maturation. Children get stronger as they grow, largely because their muscles increase in size. They can perform better on aerobic endurance events because their legs are longer (which translates to longer strides) and they have bigger hearts and circulatory systems. And so on. So, the actions of growth hormones and other growth-promoting agents are mainly responsible for these steady improvements in sport abilities with age.

Rowland: Now you have to picture figure 6.2, Bob, which points out the next step: This curve of improving performance abilities during childhood is affected by genetics. If you think back on the second grade, before any training whatsoever, some kids in the class were very fast or very strong, and some weren’t. Some of them inherited top-quality performance genes from their parents, others weren’t so lucky. In figure 6.2, there are some parallel lines above and below that of our average child, showing that genes that alter the physical and physiological factors that influence performance can affect the curve of motor development.

Malina: I think your readers may be surprised that you can remember back to the second grade, Tom.

Rowland: An unforgettable year. Somewhere around the dawn of electric lighting.

Malina: Now, I can guess that your next step will be what happens when the child reaches puberty.

Rowland: Right. That’s when things start getting complicated. During male puberty, surges in testosterone trigger increases in height, muscle bulk, heart size, blood volume, and hemoglobin concentration, all of which improve sport performance. (Girls, on the other hand, gain more body fat, which impedes performance in some sports like gymnastics. But let’s stick to just the males for now.) So far, that’s clear. The complicating factor is that in any group of youngsters, the pubertal events that trigger all these changes occur at different ages and at different rates. For some youths, performance-enhancing pubertal changes occur early. Others experience them later in adolescence. They also occur at different tempos. Some youths go through the process very quickly in a concentrated manner, while for others, the entire process is drawn out over time. Level of sexual development, with its implications for sport performance, does not follow the youngster’s chronological age. That’s what figure 6.3 shows.

Malina: Think about the implications here. In any group of 12-year-old boys, the early sexual maturers are generally stronger, faster, and more athletically talented. Their hormones have beat the clock, you might say. These boys will be the standout players in youth leagues of football, basketball, baseball, and soccer. It might be supposed that that the late maturers will eventually catch up. By the end of the pubertal period, the effect of differential biological maturation should be reduced, perhaps even erased. The conclusion could be made, then, that trying to predict ultimate basketball talent in college, say, by how a child performs at age 12 might be entirely treacherous, if not impossible. The same applies to other sports. Though early-and late-maturing soccer players differ considerably in size and strength at 11 or 12 years of age, they do not differ that markedly in soccer-specific skills. A key question then becomes how can we protect the small, talented youngster in a given sport?

It’s very interesting, then, that the first conclusion—early maturers will be more skillful at younger ages—is true, but maybe the second—that it all evens out in the end—is not. This comes to light when sport success is analyzed by birth date. Since competition is grouped by age category in most youth sports, a child who is born at the first part of the qualifying year can be expected to be bigger—and perhaps more skillful in strength and power activities—than one whose birth date is in the later part of the year. Yet both will be playing at the same level of team competition.

Malina: Numerous studies have documented this effect.1 Rosters of participants in youth sports, particularly hockey, are biased toward those with birth dates in the first portion of the year, as compared to the last. The usual explanation is that those who are chronologically older are also more likely to be more biologically mature—stronger, heavier, and taller—offering a competitive advantage. No surprises here. Yet it is intriguing that this same bias for early birth date is seen in highly successful young-adult athletes after puberty as well. Studies of competitors in professional baseball, ice hockey, soccer, and basketball have all indicated a skewing of birthdates toward the quarter of each sport year. Somehow, the early maturers, who are more talented early on, seem to have continued to dominate in their sport. How to explain this? I believe that the size and performance advantages of early maturing boys within their respective age groups attract the attention of coaches and others interested in the search for talent.

Rowland: Before leaving this point, it should be added that in addition to birth date, location of birth also seems to be important. If you want to be a star athlete, grow up in Austin, not New York City or Miller’s Corners. Well, that’s a bit of hyperbole, but the point is that studies indicate a disproportionate number of professional athletes grow up in cities with populations less than 500,000 but greater than 10,000. Psychosocial environment seems to have some importance in the pathway to sport success. For example, Jean Côté and coworkers reported that about half of the U.S. population lives in cities with more than 500,000 inhabitants, but these cities account for only 13% of National Hockey League players, 29% of professional basketball players, 15% of participants in major league baseball, and 13% of the players in the Professional Golf Association.2

Malina: Agreed. Did they provide any explanation for these findings?

Rowland: Well, you can pick your favorite explanation among the many offered: better physical environment of the smaller cities with more unstructured play activities permitting experience in different sports, more local support for sport teams, less competitive milieu, greater chance for early success, and so on.

Malina: So, where did you grow up, Tom?

Rowland: Alma, Michigan.

Malina: That explains everything.

Rowland: Could be. So, remember, we have been talking here about the steady, normal improvements in motor performance that occur as children grow. No training, just normal development, governed by growth-promoting hormones and affected by genetic endowment and level of sexual development.

Malina: We should add a third component, behavioral development, to this normal progression, too. This is a cultural concept. In their social milieu, children develop cognitively, socially, emotionally, and morally—they are learning to behave within the constructs of our society. This also applies to motor development and sports, specifically societal expectations and rewards associated with proficiency or lack of proficiency. The demands of sports may influence, or even sometimes conflict, with this normal behavioral development.

All three of these trends—physical growth, biological maturation, and behavioral development—are in a state of constant change and interaction during childhood and adolescence, and the rates of change and interactions vary greatly from one child to the next. So when thinking about the effects of sport training on children, we must appreciate that adult-organized programs are superimposed on a constantly changing base.

Rowland: Let’s turn now to the effect of athletic training on the natural progression of events. To what extent can athletic training accelerate the normal improvements in physical performance of children and adolescents as they grow (that is, beyond the stimuli provided by Mother Nature)? And, as a corollary, can a child’s ultimate development into a performing athlete be enhanced by early sport training?

Just to be clear, by training, we mean a program of systematic instruction and practice of certain frequency, intensity, and duration. That improvement in sport skill should be achieved through training is based on the precept that regular exercise stresses body tissues, which, in response, compensate by improving function. That function is then translated into greater performance outcomes. Also, in sports involving complex neuromuscular skill, such as tennis, there is the concept that repeated practice grooves neuromuscular connections, providing a kind of muscle memory.

Malina: It should be readily apparent that when thinking about the applicability of these principles to youth, a number of considerations are important. For instance, are the children at a proper stage of readiness or preparedness to respond to such stimuli in terms of their personal stages of growth and development? Are there critical periods when children are optimally sensitive to improvements associated with instruction and practice (in the case of sport skills) and physical training (regarding biological dimensions and functions)? How do differences in coaching strategies and instructional techniques at different ages make a difference? Our understanding of these issues is very limited.

At what age should highly trained athletes be expected to reach their peak performance? Obviously, it depends on the sport, and many exceptions to the rule exist. But researchers have committed serious effort trying to pinpoint these average ages. As you thumb through the literature, here’s what you’ll find:

Baseball players tend to reach their peak pitching and hitting capabilities at 28 or 29 years of age. In tennis, top performance is typically reached at age 24, in golf at 31. In track-and-field events like the shot put, high jump, and pole vault, the peak is usually in the mid 20s. Figure skaters, early 20s. As a general statement, females tend to peak earlier than their male counterparts. There has been a recent trend—tennis is a good example—for greater expertise in younger competitors.

Gymnastics has an interesting story. Many years ago, champions in women’s gymnastics were typically in their 20s, and some were much older. In the 1956 Olympics, the individual gold medal went to Hungarian gymnast Agnes Keleti, who was 35 years old. As time went on, the average age of female Olympic gymnasts fell, and medal winners in their mid and late teens were common. As the difficulty in gymnastics increased, so did the intensity of training. In response to concerns of exploitation as well as physical and psychological injury, a rule was instituted in 1976 that competitors had to have reached their 14th birthday. The minimum age for competition in senior-level events has since been raised to 16 years.

In 1994, before the latest age restriction, the average age of international gymnasts was 16.5 years. In 2005, after the new limit, it was 18.1 years. Not all have been in favor of the new minimum age. For gymnastics success, girls need to be favored by small stature, light weight, low body fat, flexibility, and what is called a good strength-to-weight ratio. All of these features can be unfavorably altered at puberty, when the body’s center of gravity also changes. Peak performance, at least from a physical standpoint, might occur not long after—if not before—the age of 16 years. Male gymnasts, on the other hand, have a later development of strength-to-weight ratio that is optimal in their early 20s.

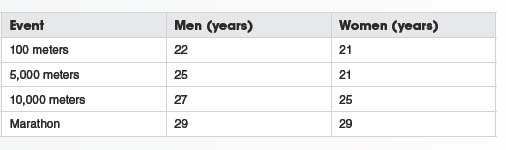

One of the most intriguing observations lies in the realm of peak performance in running events. Although some discrepancies among different reports exist, here are the average reported ages by gender:

Notice any trends here? Again, the women seem to peak earlier than the men. But you’ll also see that the longer the race, the older the peak performers. (Those readers approaching the later decades of life can do some arithmetic to figure out at which distance they should now peak out.)

Rowland: Let’s begin by considering some examples of physiological fitness. Like muscle strength. It wasn’t that long ago that people felt that it was impossible, and maybe even dangerous, for children to try to improve their muscle strength with resistance training, like lifting weights, before puberty. It was thought that you had to have circulating testosterone to do this. But now we know this is false. A good number of studies have documented that children, both boys and girls, gain strength in properly designed programs, just as adults do. So, we should expect that weight training would help children improve performance in sporting events where strength is an issue, most directly in, say, wrestling or powerlifting, but also in football, swimming, and even baseball. The studies haven’t been done yet to really prove this, but it makes sense.

Aerobic endurance performance, like distance running, is associated with  O2max, the highest amount of oxygen utilized by the body in an exercise test on a cycle or treadmill. With a period of aerobic endurance training, children typically show a rise in

O2max, the highest amount of oxygen utilized by the body in an exercise test on a cycle or treadmill. With a period of aerobic endurance training, children typically show a rise in  O2max, on the average about 5 to 6%. Since that number is less than what is observed in adults (15-20%), some have suggested that this implies that prepubescent children might be less trainable than adults in aerobic endurance sports. But it is not clear if the dampened response of

O2max, on the average about 5 to 6%. Since that number is less than what is observed in adults (15-20%), some have suggested that this implies that prepubescent children might be less trainable than adults in aerobic endurance sports. But it is not clear if the dampened response of  O2max to training in children can be translated into a similarly limited increase in aerobic endurance performance itself. That’s because performance on, say, a 5K road race is dependent not only on

O2max to training in children can be translated into a similarly limited increase in aerobic endurance performance itself. That’s because performance on, say, a 5K road race is dependent not only on  O2max but also on factors like economy of running energy.

O2max but also on factors like economy of running energy.

Malina: Youth athletic programs place a major emphasis on improving motor skills that are more specific to sports, such as throwing, jumping, and ball kicking. Given this focus, it is rather surprising that a very limited amount of research exists on the trainability of such abilities in children. Equally lacking are data to indicate whether particular instructional techniques are more effective than others. And we know little about the influence of variables such as environmental constraints, peer influence, and parent modeling. But from the few investigations that have been done, it does seem that instruction and practice on early acquisition of motor skills is beneficial in improving motor performances in early childhood years (ages 3 to 7).3

Even less scientific data exist on the effect of specific instruction and training on gains in sport skills at later and higher levels of competition. It is taken for granted, even by the casual observer, that sport-specific skills generally improve during the course of a season. But, again, the available studies generally support trainability in older children of capabilities in activities, such as baseball pitching, basketball shooting, and soccer skills. Certainly the skill development that appears to occur in the setting of dedicated intensive sport schools involving tennis, skating, and gymnastics would support the meager scientific evidence that youths can respond with significant improvements in performance following appropriate training regimens.

An important area that has lacked previous attention here is the environment of instruction, practice, and coaching in highly specialized programs in all sports. Moreover, I doubt that high-level coaches want their programs systematically studied! If you follow media reports, you’ll see that there is much to be desired.

Rowland: So, to sum this up, it does appear that children and adolescents can, in fact, respond with improvements in athletic performance in response to adult-organized training programs. It is reasonable to conclude that the effectiveness of such training depends on the physical and cognitive readiness of the individual child, and that youth training programs need to be designed with this in mind.

But a good many questions remain. If your goal is to produce a high-performance athlete, when in the course of childhood should intensive training be instituted? How can the child who has the capacity for such development be identified? What about the concerns regarding the ethical aspects of early, intense sport training in children? That is, maybe we can train children, but should we? Bob, I hope you have the answers to all these questions.

Malina: Right. And I would add another aspect to your summary—that distinct individual differences exist in responsiveness to instruction, practice, and training programs.

To start with, we can talk all day about these issues, but, in fact, the reality is that the rush to train child athletes continues unabated. We only need to consider parents awakening at 5:00 a.m. to drive their 7-year-old to the hockey rink, the national traveling teams for 10-year-old basketball players, the private coaches and training programs focused on developing child talent, parents holding their children back a year in school to gain an athletic advantage. As Dan Gould has put it, whether we like it or not, we are witnessing the “professionalism of child sports.” You can also add the influence of the sporting goods industry to the mix.

Rowland: And whether we are witnessing parents’ laudable desires to have their children enjoy themselves and fulfill their physical abilities or, beyond certain limits, children being placed in highly intensive sport training to satisfy the vicarious needs of parents and coaches (in fact violating child labor laws and constituting child abuse) is open to acrimonious debate. So, as we discuss the scientific merits (or lack thereof) of training children, we need to keep in mind the strong cultural and societal forces and sharp controversies that exist on these matters beyond the simply scientific.

Malina: Let’s pretend for a moment that we have the luxury of avoiding such conflicts, and dispassionately examine some ideas about what might be the wisest approach, from a scientific standpoint, to developing young talent. There are, in fact, two major camps on this issue. One holds that a certain amount of practice and training is obligatory for talent development. This must be accomplished in a finite amount of time. Consequently, early sport specialization in the growing years is requisite for high-level play, particularly in sports in which peak performance occurs early, like the teen years for gymnastics. The other camp argues that basic steps of developing athletic skill during childhood must occur in stages that incorporate early generalized exposure to different physical activities. This concentration in a particular sport should not occur until later childhood, early adolescence, or perhaps later, depending on the sport. These people argue, too, that “too much, too soon” results in burnout and injuries that will inhibit long-standing participation in sports, rather than encourage it.

Rowland: Let me talk about the first point of view and then get your opinion. Let’s suppose I’m, say, 16 years old, and in the excitement of watching the summer Olympic Games on television, I’m struck with the idea of training hard to become a medal winner in the 5,000-meter run. So, I start a training regimen of regular running, increasing my distance. What will happen to my 5K race times? At the start, I will find rather dramatic improvement from race to race, but as time goes on, that rise in performance will slow. After a few months, I will probably see little change over time, even though I’m still training. And, guess what? My 5K time for that plateau will not be anywhere near what I saw at the Olympic event.

This is the pattern of the typical power law of practice. By the traditional explanation, I have reached my genetic limit for distance running performance. By hereditary constraints, I can never match those Ethiopian runners taking the medals at the 5,000-meter event. I’ve reached the upper limits of my inherited capabilities and can’t surpass them, even with training.

K. Anders Ericsson and his colleagues at Florida State University, among others, have challenged this premise. They would tell me I reached my limit, not because I hit a genetic-determined ceiling, but rather because I failed to employ proper training techniques. They argue that “distinctive characteristics of exceptional performers are results of adaptations to extended and intense practice activities that selectively activate dormant genes that are contained with all healthy individuals’ DNA.”4 Those potentiating training techniques are labeled deliberate practice, meaning highly focused coach-guided sessions that solely concentrate on improving certain aspects of performance. Simply repeatedly performing the activity, the way I did with my daily runs, will not get me by the plateau. But, with sustained deliberate practice, high levels of performance can be attained.4

How long does this take? Ericsson and his coworkers developed their ideas from their studies of musicians—pianists and violinists—showing that performers at the highest level exhibited more deliberate practice patterns. These elite players started training at an earlier age than less-talented performers. A retrospective analysis indicated that these top musicians had accumulated a greater number of practice hours—approximately 10,000 by the time they reached 20 years of age.

Previous studies of chess players suggest that it takes about 10 years to develop the highest levels of grand master expertise. That number was consistent with what Ericsson and colleagues saw with the musicians. The 10-year rule (minimum for this threshold) for achieving elite expertise seems to hold up for athletes, too. People who have examined the courses of development of champion swimmers, distance runners, and tennis players have observed the same thing—elite performance requires at least 10 years of deliberate practice. Researchers have estimated the number of training hours for elite athletes that might be involved over this time span, and it also comes out to somewhere around 10,000. So, we have the popular notion that 10 years and 10,000 hours of practice—the right kind of practice—are necessary to make you a champion athlete.

As the last chapter notes, the weakness of this numerical reasoning is that it is based on a retrospective analysis. Nothing in this information tells us about causality. It could be that naturally highly talented performers are motivated, or have greater opportunities, to practice more.

Anyway, if you believe all this, it is apparent that commitment to sport specialization and intensive training would need to begin early in childhood. Athletes in most sports should be at high levels of performance at least by the time they reach their 20s (and in some cases, like gymnastics, tennis, and figure skating, much earlier). So, a little arithmetic tells us that if would-be champions have to get in all those years and hours, they should be in the gym regularly, with structured coaching, early in their elementary school years.

That parents should believe in this idea is fueled, of course, by the stories we all know of some of the world’s very greatest athletes—Andre Agassi, Tiger Woods—whose parents had them training regularly from the time they were toddlers. (I understand that Tiger once beat the comedian Bob Hope in a putting contest on a TV show when he was only 3 years old.) What is ignored here, obviously, is the denominator in such stories. How many 4-year-olds who took daily private tennis lessons at the local club never achieved success?

Perhaps it should be pointed out here that the reader should not confuse the train-them-early approach to sport success with attempts to identify child sport prodigies (we’ll be discussing this more a bit later on). When those researchers looked at the course of development of eventual star athletes, they generally found that these elite competitors were not exceptionally gifted early on. They didn’t make accelerated improvements in performance with training, either. Their success was gradual. Instead, it seemed related to starting early, gaining access to superior training opportunities, and having the advantage of talented coaches and supportive parents and siblings.

Malina: I wonder if the impact of early sport success is not underrated in these kinds of analyses. Children who find themselves doing well when first getting into a particular sport get a lot of ego-fulfilling feedback and, often, the indulgence (wanted or not) of coaches and other adults. Children who start out playing poorly are not motivated to continue and are often eliminated from the sport system—either voluntarily (dropping out) or involuntarily (being cut from the team). Children, like adults, do what they’re good at and what they enjoy doing.

Rowland: So, Bob, I have lots of questions for you. What do think of these rules of 10 and early sport specialization in children? Let me really pin you down on this: The father of a 3-year-old who lives next door is determined that she be an Olympic gymnast. He asks you if it’s too early to get her into a training program at the local sport club. What do you tell him?

Malina: Tom, I would first ask the father to think about the following questions: Is this for his child or for himself? How does he evaluate the adults who run the program? If it is a developmental gymnastics program that is child-centered and emphasizes basic movement skills, I would have no trouble recommending that he enroll his child. However, he should be sensitive to his daughter’s response to the program. Is she really enjoying it? (Young children will not often let on directly, since they want to keep their parents happy. She will, however, tell you indirectly with behavior, comments, and play activities with toys at home.) Try to find out if she really wants to do this. Unfortunately most parents do not listen to their children, talking at them rather than with them.

When I talk to parents about early initiation of sport training during the preschool years, I raise issues (actually red flags) related to the careers of Michael Jackson, Tiger Woods, and other elite individuals who attained success at a relatively young age. I am convinced that preoccupation with a single activity beginning at a very early age, attainment of success at a young age, preferential treatment and indulgence by adults, and the entertainment or sport systems, all influence and perhaps lead to the arrest of other dimensions of normal behavioral development. It is likely that athletes who became successful and specialized at young ages have missed out on many valuable experiences in the normal process of growing up.

To make a long story short, I would encourage the father not to enroll his child in a program aimed at sport specialization at an early age. Childhood should be a smorgasbord of experiences—group and solitary play, social interactions, school, and so on—from which children can learn the broad range of behaviors expected of society.

Rowland: Another school of thought holds that this emphasis on early sport specialization by young children is misguided and may even be detrimental to their future athletic success. The argument is that, yes, elite athletes often have started sport involvement at an early age. Most typically, though, they participated in a variety of activities, not just one, and specialized intensive training in a particular sport did not occur until later on. This pattern of delayed specialization, its advocates contend, provides for better overall development of fitness and motor skills, preventing early athlete burnout and injuries.5

In sports like figure skating and gymnastics, in which performance must peak in the teen years, early specialization would seem to be required. But for most other sports, this isn’t true. Research bears witness to participants in tennis, field hockey, and soccer who accelerate their training to reach elite levels during the teen years. Competitors who turn out to be expert baseball, rowing, and basketball players have usually involved themselves in a number of different sports early on.

The advantages of this early diversification are supported by certain developmental constructs that cite the value of generalized (rather than specific) motor skills, of playlike participation, and physiological cross-training between activities. As the argument goes, it provides time for the development of intrinsic motivation and other psychological skills important for high-level training (self-confidence, ability to concentrate, capacity for strategizing, and so on).

This approach, its proponents contend, avoids certain risks associated with early sport specialization during childhood. These include impaired psychosocial development from the social isolation that occurs with early training, overuse injuries, and rates of burning out or dropping out.

Tudor Bompa, the famous sport coach who developed young athletes in Romania behind the Iron Curtain in the 1960s, has been one of the strongest advocates for multilateral sport involvement for children at young ages. His experience in the Soviet Union at that time shows the following:

• Most young athletes had a diversified early involvement in sports

• Specialized programs were commonly withheld until 15 to 17 years of age

• Peak performances were achieved 5 to 8 years after specialized training

The children who began sport specialization at an early age demonstrated peak performances at a junior age level. However, these performances were not duplicated when they reached maturity (18 years). Many, in fact, dropped out of sports. Those who had a diversified early sport experience had a slower rate of improvement in performance, peaking at a later age, but demonstrated a high level of persistence and fewer injuries.6

Bompa comments, “Specificity training results in faster adaptation, leading to faster increments of performance. But that does not mean that coaches and athletes have to follow it from an early age to physical maturation. This is the narrow approach applied to children’s sports, in which the only scope of training is achieving quick results, irrespective of what may happen in the future of the young athlete. It’s important for young children to develop a variety of fundamental skills to help them become good general athletes before they start training in a specific sport.”

Malina: I agree with Tudor Bompa on multilateral training and the importance of learning a variety of basic skills. But in the former Eastern European sport systems, the multilateral training was essentially under adult supervision at all times. The youth trained within specific sport programs. What is lacking in this approach is time for the youngster to be a child or adolescent, which means participation in informal street games.

Unstructured sport activities are by definition uncharacterized by explicit teaching and adult supervision. They involve much trial and error, experimentation, and unstructured repetition, or practice. It is postulated that skills learned under informal conditions are influenced less by fatigue and stress. Street sports and other unstructured activities obviously vary with the number of youths available and generally change with the season, exposing them to different skills and rules. Such activities in all likelihood involve the learning of sport skills without awareness or explicit knowledge of them. The same can probably be said for social interactions and development.

Rowland: I like Jean Côté’s take on this issue. He and his colleagues have emphasized that in the optimal approach to early training, sport skills are learned that are appropriate to the child’s stage of growth and development. They believe that the essence of deliberate practice, with its hours of focused work, delayed gratification, and need for self-control, is not yet in the grasp of most preadolescent athletes. “By the time athletes reach adolescence,” they say, “they will have acquired fundamental movement skills though deliberate play and will have developed mature cognitive skills. At this point, an appropriate shift in training would include more complex kinds of learning and deliberate practice activities.”7 So, they’re saying that, yes, sustained deliberate practice is important, but, no, young children are not yet developmentally ready for this type of commitment.

So, what we’ve been discussing here is talent development, how athletic potential can best be realized through training, all within a limited time span. You can see that no one’s quite sure. If I might be so bold as to try to summarize: It seems the conflict lies between constraints of time available for deliberate practice and the developmental readiness of the young child. If all children were the same in such developmental progress—physically, psychologically, socially—it would all be at least a bit easier. But, no.

Malina: I, too, agree with the approach of Jean Côté, but the issue goes beyond the relatively simple dichotomy of time constraints for deliberate practice and developmental readiness. This viewpoint overlooks the normal demands of growth, maturation, and development—that is, the normal demands of growing up. I personally believe it is abnormal for a child to willingly and knowingly devote several hours per day to the specific repetitive practice of a sport or musical instrument. If it truly was the child’s choice—and not that of an overinvolved parent—I might modify my view. But it seems to me that children have too much else to do, engaging in play that is free, imaginative, and social.

Rowland: Now that we’ve got that all nailed down, let’s move on and talk a bit about early talent identification. How can we initially identify the special child who is ultimately destined for athletic stardom, the one who deserves coaching and developmental training programs? Certainly it would be hard to overstate the importance of this issue to those whose careers—reflecting the success of teams, their universities, cities, and nations—are focused on producing elite athletic talent.

Malina: There are a variety of approaches to early talent identification, but the structured approach that was characteristic of Eastern European countries and, more recently, of China has received the most attention. In this method, which is sometimes labeled the scientific approach, young children are identified through screening at an early age, usually on the basis of general motor proficiency (motor development) and physical characteristics. Those doing the screening have a general idea of the physical characteristics associated with specific sports. Those who are so identified are then directed into specific programs for more specialized evaluation. Ages at screening, it should be noted, vary with the sport.

Take diving, for example. In addition to height, weight, and physique, strength, speed, power, muscular endurance, and flexibility are basic components of fitness required for the sport. You could also add spatial orientation, balance control, rhythmic sensitivity, and acoustic and optical reactions as being important perceptuomotor characteristics of a talented diver. Youths who score well on tests for these characteristics may be selected for diving development programs.

The same may be done for team sports. Soccer, for example, requires speed, power, agility, and aerobic endurance, in addition to control of the feet and body, accuracy in shooting and passing, and perceptuocognitive skills. Youths who score well on a battery of tests of these abilities would likely be identified for soccer development programs.

This is a classic approach that’s been used for many sports, especially in the selection programs in Eastern European countries. It is being used now in some sports in Australia and China. On the surface, at least, it seems to have shown success. However, you only hear about the successes, and you don’t know the denominator in the equation to calculate success. The basis of this approach, of course, lies in the assumption that early sport-related traits are predictive of those later on. The problem is, as noted above, there is no way such a supposition can be expected.

Here’s a word of caution about the sport selection programs in Eastern Europe. Tudor Bompa has highlighted the success of the talent identification programs in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR) and Bulgaria, in which 80% of the medalists came from this type of program. The success of the GDR athletes was especially evident in swimming, particularly for females. However, 12 years later, attention was brought to records of hormonal doping of these competitors. One can thus ask, were the athletes selected or were they experimental subjects?

Rowland: So, I would guess that with this approach, there would be a large number of dropouts, or failures. At the same time, some athletes who matured later but had the potential for success would be missed altogether.

Malina: You are correct. In the structured systems, you only hear about the successes, and you do not know the denominator for the equation to calculate success. Nonetheless, sport governing bodies have made major investments in the method. It’s not difficult to see that a good number of other problems exist in taking this route to identify early signs of athletic talent. Clearly, the physical and physiological measures that are being used don’t really get at all the factors that go into talent. Sometimes athletes can be very successful by compensating in one area for another in which they aren’t so strong. Yet, they’d flunk the testing battery based on that weakness. And psychological qualities, which are so critical for sport success, are generally totally ignored. Of relevance for team sports, too, is game intelligence. A youngster may have the requisite physical and skill characteristics, but may not be able to see the field in soccer, anticipate a pass, move to a space, and so on. Overall, the predictive value of early testing batteries has to be very low. Obviously, the older the child when such testing is undertaken, the better the results in terms of predictability.

Rowland: Attempts at early identification of sport talent are extraordinarily complex. We’ve got all these determinant variables that are changing as the child grows. Between different youngsters, the rate of change varies and the outcome level of skill and its timing seems quite unpredictable. It’s interesting that people who have a keen interest in analyzing multilayered, multifaceted problems like this—they’re called dynamic system theorists—have actually given a good deal of thought to the issue of early talent identification. They’ve likened the nonlinear dynamics of talent development to chaos theory, in which very small perturbations in initial conditions can create major amplifying effects. That makes outcome prediction essentially impossible (long-term weather forecasting being the model).

Writing in the journal Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, Angela Abbott and her coworkers in Edinburgh have commented that “while this message suggests a rather bleak outlook for those wishing to predict future characteristics or behaviors of an athlete (that accurate long-term predictions are impossible), an important distinction must be made. Human performers possess a critical quality (to a greater extent than other chaotic systems) in their ability to display intentional, goal-directed behavior. Humans can be seen as deterministic organisms…. and individuals with sufficient drive and determination are more likely to overcome barriers and physical shortcomings in order to be successful in the future than those who do not possess such qualities.”8

Malina: If I understand the dynamic systems approach to motor development and skill acquisition correctly, the process involves the interactions of three constraints: the child or performer, the environments (natural, manmade, and social), and the specific movement task. These all change and interact as the child grows. Specific instruction and practice represent a manipulation of only one component of the environment. This element is undoubtedly important in skill development, but it cannot be treated in isolation from other components of the environment and, of course, from the child himself.

Rowland: The other major approach is more informal, promoting mass participation in a sport by young children and then letting those with the most talent identify themselves as they grow older. This method has been called weeding out, letting the cream rise to the top, or the last man standing.

Malina: This is the usual early-selection process in the United States and westernized countries (one thinks particularly of swimming, soccer, and baseball) in which there is a large pool of young athletes. The focus is more on demonstrated performance rather than on physical characteristics and specific test skills that characterize the more structured approach.

American football and basketball are somewhat in between, given the emphasis on size as a selective factor. So, the seemingly informal programs may be more formal than meets the eye. Youngsters participating in these sports are under constant observation and scrutiny, especially by other coaches, interested adults, school and club administrators, potential agents, and athletic management programs. These adults are looking for talent, which from their perspective is essentially a commodity to be marketed. Once athletically gifted children are noted, these adults may try to enroll them in select programs or on a travel team. In some cases, they may encourage parents to enroll their children in a specific middle or high school. What I am trying to say here is that the seemingly informal programs have a very formal dimension when it comes to youths who have demonstrated their talent in local competitions.

Tudor Bompa has correctly noted that there is an element of chance here—the development of a child’s athletic potential would rest on the chance that he chose to participate early on in a sport for which he had ultimate talent. How many extraordinary lugers are there in the United States who never participated in the sport? How many Michael Jordans are hidden in the Inuit population?

Rowland: Which approach do you think is best?

Malina: There’s no simple answer to this question. There are too many variables involved in this process of talent identification and development, most of which are beyond the control of coaches, the sport system, and even the athletes themselves. To start with, how would we even define success? Many would look at the medal count in the Olympic Games. But what we’re seeing there is only the numerator of our question—those who are successful. We usually don’t have information regarding the denominator, or the total number of athletes identified and selected.

What is the chance of success from participation in youth sport at the elite level? It’s not very high! Here’s an example. In Russia in the 1990s, 2 million youths 6 to 15 years old were said to be participating in sports, which was around 10% of that age group. Of these, 35,000 enlisted in specific sport-training schools. This number was narrowed down to 2,700 who competed on national teams. Of these, 49 were considered to be competing at elite levels. That turns out to be 0.14% of the athletes who were enrolled in intensive sport training. People have done this kind of analysis and found similar success rates for the Chinese at the Beijing Olympics in 2009, elite sport schools in Germany, and the probability that a high-school athlete in the United States will move into the professional ranks. The nature of sport is selective and exclusive!

Tom, I don’t think we can allow ourselves to close this topic without offering a summary of personal opinion.

Rowland: Let’s do it. We’re probably safe. Most readers have probably dropped out a few pages back, anyway.

Malina: Early specialization in a year-round sport has become increasingly common for talented young children. Many factors are responsible for this trend, including pressure from parents, the desire for scholarships or professional contracts, the goals of the sporting goods and services industry, and even ourselves, the sport scientists. The early careers of most high-level athletes, on the other hand, are marked by experiences in a variety of sports before specialization. The risks of doing too much, too soon are great—social isolation and manipulation, burnout, and overuse injuries. It’s important for us to keep youth sport in perspective. Young athletes are children and adolescents who have the needs of children and adolescents.

1. A review of the age effect on youth sports can be found in the following article: Musch, J., and S. Grondin. 2001. “Unequal competition as an impediment to personal development: A review of the relative age effect in sport.” Developmental Review 21:147-167.

2. Côté, J., D.J. MacDonald, J. Baker, and B. Abernethy. 2006. “When ‘where’ is more important than ‘when’: Birthplace and birth date effects on the achievement of sporting expertise.” Journal of Sports Sciences 2: 1065-1073.

3. For a review of studies examining the acquisition of motor skills in youth through sports training, see the following article: Malina, R.M. 2008. “Skill acquisition in childhood and adolescence.” In The Young Athlete, ed. H. Hebe-streit and O. Bar-Or, 96-111. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

4. Anders Ericsson, K., K. Nandagopal, and R.W. Roring. 2009. “Toward a science of exceptional achievement.” Annals of New York Academy of Sciences 1172:199-217. Ericsson, K.A., R.T. Krampe, and C. Tesch-Romer. 1993. “The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance,” Psychological Review 100: 363-406.

5. This article gives a nice outline of the early specialization versus early diversification debate: Baker, Joseph. 2003. “Early specialization in youth sport: A requirement for adult expertise?” High Ability Studies, 14: 85-94.

6. Bompa, Tudor. 2000. Total training for young champions. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

7. For an argument against early sport specialization, read the following: Côté, Jean, Joseph Baker, and Bruce Abernethy. 2003. “From play to practice: A developmental framework for the acquisition of expertise in team sports.” In Expert Performance in Sports, ed. J.L. Starkes and K. Anders Ericsson, 89-114. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

8. Read about theoretical models of sport talent identification in the following articles: Abbott, A., C. Button, G.J. Pepping, and D. Collins. 2005. “Unnatural selection: Talent identification and development in sport.” Nonlinear Dynamics Psychology and Life Sciences 9: 61-88. Vaeyens, R., M. Lenoir, A.M. Williams, and R.M. Philippaerts. 2008. “Talent identification and development programmes in sport.” Sports Medicine 38: 703-714.

1. Athletic performance reaches a peak during the first portion of life despite continued training. The age at that zenith varies by sport, but all competitors have a certain limited time for optimizing success.

2. Most of the improvements in athletic performance with training occur during the growing years of childhood and adolescence. During this period, motor abilities normally improve due to physical growth and sexual development, though the rate of such gains varies considerably from child to child.

3. Limited data suggest that children can respond with improvements in fundamental and sport-specific motor skills with appropriate sport training.

4. Variations in timing (when) and tempo (how rapidly or slowly) of biological development that are associated with increases in size and strength (males) and body fat content (females) at the time of puberty can affect prediction of future sport success.

5. Two schools of thought dominate talent development: early specialization necessitated by a limited time for skill development (particularly in sports like gymnastics, in which performance peak is early) and early multilateral involvement in sports with later specialization to allow overall fitness gains and to lessen risk of dropout and injuries.

6. Early identification of sport talent is considered important by adults involved in sports but is, in fact, difficult to achieve. The two most common approaches are (a) use of sport-specific physical and physiological profiles and (b) identification of superior performers out of mass participation. Shades of variation exist between the two extremes. The relative success of these two strategies is difficult to ascertain. There are simply too many intervening factors.