Chapter 2. The Evidence?

The weight of evidence for an extraordinary claim must be proportioned to its strangeness.

— Marquis de Laplace

Given the returns that the commercial software industry has generated historically and is still generating today, the typical reaction to the hypothesis that realizable commercial values of software as a standalone entity are in decline is skepticism. Which is entirely appropriate, given the extraordinary nature of the claim.

In 2013, Microsoft’s Windows and Office (Business) divisions collectively generated $44 billion in revenue, up 4% from 2012, which was in turn up 3% from 2011. In one year, then, Microsoft generated more from two software products than VMware, Yahoo!, Salesforce, Adobe, Twitter, Nokia, Netflix, or Intuit are worth as companies. How then does one construct the argument that it’s becoming more difficult to sell software, at Microsoft or more broadly?

With Microsoft, it’s surprisingly simple. It is true that Microsoft continues to excel at generating software revenue. Even if we allow that this is largely an artifact of that rarest of achievements—a true monopoly—the company’s ability to maintain its dominance over decades despite fierce competition and an industry that is always in change around it proves one thing: Microsoft can make money with software. The question with Microsoft, therefore, isn’t whether they can make money, it’s whether they can make money as efficiently as they have in the past. Because if one looks beneath the surface of their financials, there appear to be cracks in the façade.

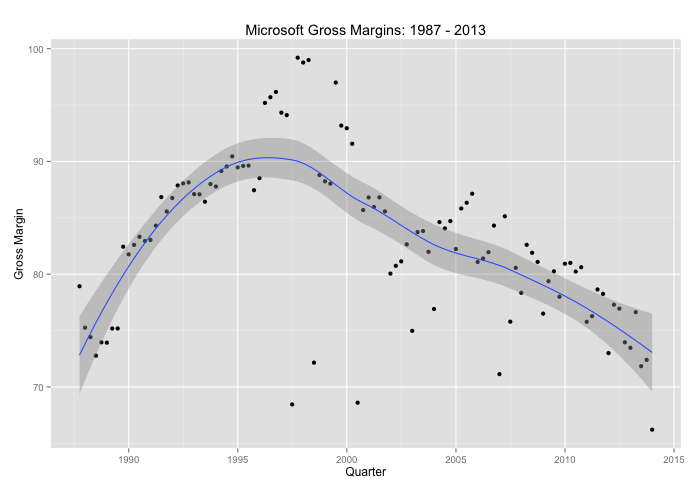

Microsoft’s ability to generate revenue remains unchallenged, but their ability to extract profit from that revenue has proven more difficult to sustain. In the third quarter of 1987, one year after going public, Microsoft posted a quarterly profit margin of 79%. At its peak in 1999, Microsoft would post an average profit margin of 93%. Since the first quarter of the year 2000, they have never again broken the 90s. Microsoft’s margin in the last quarter of 2013, meanwhile, was its worst ever at 66%. The following chart depicts Microsoft’s gross margin over time (with a line of best fit and confidence interval).

For Microsoft and its shareholders, the trajectory implied here is troubling. Microsoft retains an unparalleled ability to generate revenue from software, but given that it’s able to generate less profit from that revenue today than it did a year after going public, it seems important to question the mechanics of its model moving forward. As the company seems to be doing: it’s no accident that Steve Ballmer’s replacement, Satya Nadella, came from Microsoft’s cloud team. Nor that the company is releasing free versions of its operating system and office suite for mobile, or that it was willing to risk partner relationships and commit massive financial resources to enter hardware markets in both cloud (Azure) and mobile (Surface). It may or may not be an accident that Bill Gates is currently on track to have no direct ownership of Microsoft in four years.

Other software-first industry players are in the midst of their own transitions. For the first time in almost five years, German software provider SAP initiated widespread job cuts over the summer of 2014. Their purpose? Jim Dever, a spokesman for the company, told Bloomberg that the “company is eliminating jobs across divisions as it seeks to move faster and deliver more of its products as online cloud-computing services instead of software that runs in customers’ data centers.” As with Microsoft, which built itself on the sales of on-premise software, SAP is compelled by the market to change the very nature of its business.

But is the Software Paradox truly a systemic, industry-wide issue, or is it better characterized as mere failures of execution? To explore this question, we need to broaden our scope. In May 2013, the consultancy PwC compiled a list of the Top 100 companies in the world as measured by software revenue, the Global 100 Software Leaders. Here are the top 25:

- Microsoft

- IBM

- Oracle

- SAP

- Ericsson

- Symantec

- HP

- EMC

- Computer Associates

- Adobe

- VMware

- Fujitsu

- SAS

- Intuit

- Siemens

- Dassault Systemes

- Autodesk

- Salesforce

- BMC

- Hitachi

- Infor

- Sage

- Cisco

- Intel

- Citrix

If you examine the companies that make up that list, one commonality that leaps out is their age. The average Top 25 software company, by PwC’s metrics at least, is around 46 years old. But that’s admittedly skewed by outliers such as IBM, which is 103 years old, or Siemens, which is somewhat incredibly 167. The skew-resistant median, however, is 34 years of age, which means that the average large software company was founded the year that John Lennon was shot and killed, the year Tim Berners-Lee began work on the system that would lead to the World Wide Web, and the year that Lucas’ The Empire Strikes Back hit theaters.

The fact that the largest companies in a given industry are some of its oldest is, to be sure, hardly unusual. Growth through acquisition is a common pattern in most industries, and is particularly popular in technology. This is even more common in markets where high and low margin opportunities exist; the former tend to use their economic advantages to “compete” against the latter by purchasing them. From a pure development model perspective, larger technology vendors have long outsourced research and development to startups, believing that the cost of the acquisition premium is more than offset by lowered risk and costs with better product predictability. Paul Graham described this process well in a 2005 essay entitled “Hiring is Obsolete.”

Big companies also lose because they usually only build one of each thing. When you only have one Web browser, you can’t do anything really risky with it. If ten different startups design ten different Web browsers and you take the best, you’ll probably get something better.

The more general version of this problem is that there are too many new ideas for companies to explore them all. There might be 500 startups right now who think they’re making something Microsoft might buy. Even Microsoft probably couldn’t manage 500 development projects in-house.

— Paul Graham

But in a such a dynamic industry, the age of its largest entities is still something of a surprise. It should be difficult to build a long-lived software company, given the engineering preference for new problems over old ones.

Technology businesses have tended to be more vulnerable to disruption than their counterparts from other industries, as sudden advances in technology within or adjacent to a particular market can obsolete a given business’s products almost overnight. While GM has not had to worry, for the most part, about the automobile being replaced by an alternative means of transportation, technology industry players have had to weather tectonic shifts from mainframes to mini-computers, PCs to mobile, servers to cloud, and so on. Technology disruption is in part what has permitted Facebook, Google, LinkedIn, and Twitter to generate over $600 billion in collective market value in 16 years, or just about half the time the average PwC software vendor has been in existence. It’s important to note that none of Facebook, Google, et al., are included on PwC’s list, however, due to the simple fact that none of them happen to sell software directly.

Of the large, mature organizations with large software revenue streams on PwC’s Top 25, just how critical is software to their overall balance sheet? Is it their primary income stream, or merely one of multiple large sources of revenue? One would assume that because these are the 25 largest companies in the world as measured by software revenue, software would be the dominant business model among the majority of the members of the list. As in fact it is, if only a slight majority. Of PwC’s Top 25 software players, 15 (or 60%) derive the majority of their income from distributed software sales. Another way of stating that, however, is that of the 25 largest software vendors in the world, almost half do not make the majority of their money from software.

But what about the companies not on PwC’s list? If we acknowledge that the importance of software as a revenue stream is something less than dominant within the largest software earners in the world, the next logical question is what role software plays within the technology market as a whole. What if, for example, the scope was expanded yet again, this time beyond PwC’s strict subset of software-oriented vendors? If we looked for the largest “technology companies” rather than the largest “software companies,” for example, we would be able to add large players like Apple or Google. If we then sorted by market capitalization rather than estimated software revenues, that list might look something like this:

- Apple

- Microsoft

- Samsung (Consumer)

- Verizon

- IBM

- Oracle

- AT&T

- Amazon

- Samsung (LCD)

- Qualcomm

- Intel

- Cisco

- Siemens

- SAP

- Taiwanese Semiconductor

- Baidu

- HP

- EMC

- Texas Instruments

- VMware

- Ericsson

- Yahoo!

- Salesforce

This list is even more interesting with respect to the role of software. Of the 25 largest technology companies in the world on this list, 21 (or 84%) derive the majority of their revenue from something other than traditional software licensing and sales (i.e., not hardware, SaaS, or services). Broadly speaking, then, it seems clear that as important as software is to the technology industry—and make no mistake, it is fundamentally crucial—it is directly responsible for a distinct minority of the revenue, at least when sold as a standalone product.

If the macro evidence is suggestive, what about the micropicture? What about, for example, the software products themselves? Is there any evidence that the Software Paradox is manifesting itself directly within current product pricing? In nearly all industry categories, the answer to this question is yes. Consider the PC operating system market. In March of 2001, Apple debuted OS X 10.0, the first major release of its current desktop operating system. The retail cost for the product at the time was $129, or around $173 in 2014 dollars. A decade later in 2011, version 10.7, code-named Lion, was made available via Apple’s Mac App Store for $29.99. Two years after that, 10.9, also referred to as “Mavericks,” was released via the same channel at no cost.

It seems reasonable to assume that the cost of production for OS X did not suddenly drop to zero over the course of 12 years, which implies that this is a statement from Apple about the commercial value of the software. Specifically, that the company no longer felt that the operating system was monetizable. Even Microsoft, whose market capitalization was built in part on the back of operating system licensing fees, is said to be planning a free version of same.

Nor is the decline in realizable PC operating system revenue simply a consequence of the decline in importance of that market. If this were true, the category making the biggest gains at the PC market’s expense, mobile, would be expected to be a major new source of operating system licensing revenue. We would simply see a wealth transfer between PC operating system players to mobile operating system providers. Instead, the availability of Android source code and the success of Apple’s integrated hardware and software strategy has made it difficult if not impossible for vendors to replicate the retail operating system model in mobile. Microsoft has had some success generating a licensing-like revenue stream by virtue of intellectual property and patent licensing, but the viability and growth potential of that approach longer term is questionable. As for licensing of its own operating system, Microsoft has acknowledged that the market value for that is zero: it announced in April of 2014 that for devices with a screen size of 9 inches or less, its mobile operating system would be available at no cost. As explosive as the growth in mobile has been then, software licensing revenue has not been a major beneficiary. Even for mobile apps, the revenue opportunities have been limited. As Instapaper creator Marco Arment said in 2013, “Paid-up-front iOS apps had a great run, but it’s over. Time to make other plans.”

Whether the lens used is market conditions, or the performance of bellwether software entities, or even individual products, the trend is the same: it is growing more difficult to sell software up front, on a standalone basis. More important, however, the market appears to be pricing this into its valuations, favoring models that make money with software over those attempting to make money from the sales of software.

The Four Generations of Software Valuation

While this sustained decline in what has been a lucrative market for multiple decades might come as a surprise to many, the truth is that this is merely the return arc of a pendulum swing, one in which the price of software has swung wildly in one direction and now is on a return path. Consider the following generational attitudes toward software:

- First Generation (1950–1986)

- Best characterized by IBM, this type of technology provider firmly believed that software was a means to an end rather than an end in and of itself. Which, given the difficulties and expense associated with manufacturing physical hardware, was understandable. The SHARE user group founded in 1955 by IBM 701 users was one of the manifestations of this attitude; one of its major resources was its library, which consisted of patches to the operating system that were possible only because IBM made the source code for its operating system available to users. Why? Because the money was in the hardware, not the software, and anything that would improve the company’s ability to sell its hardware, such as software optimized by the users themselves, was perfectly logical. It was not until 1968, in fact, and only under pressure from the US government, that IBM began to charge separately for its software. This strategy left a variety of players vulnerable to the succeeding generation’s software monetization efforts.

- Second Generation (1986–1998)

- While IBM’s prior experience with hardware and operating systems had led it to conclude that the money was in the former rather than the latter, Microsoft’s unique realization was that the reverse might in fact be true. Believing that software represented a classic under-appreciated asset, Microsoft seized on this opportunity and built itself into one of the largest companies in history, almost strictly through revenue generated from the sales of the software it created. Just as IBM’s experiences led it to believe that the real revenue opportunity lay in hardware, however, Microsoft’s dramatic software-fueled growth led it to conclude that software was the once and future revenue opportunity, which opened the door to the next generation of provider, who again had differing ideas on the value of software in economic terms.

- Third Generation (1998–2004)

With Microsoft absorbing a disproportionate share of revenues and well placed strategically and financially to respond to competitive threats in the area of software, a new class of technology provider emerged that was built off of software, but in a fundamentally different way. By engaging directly with users via a browser, Google was able to effectively bypass Microsoft’s dominant positions in various software markets and build itself into one of the largest technology companies in the world today—all without selling so much as a single license of distributed software. Core to its success was the realization that the economics of scaling itself to a worldwide audience using proprietary software were untenable, which led the company to build itself upon open source software. This ability to construct a massive, global technical infrastructure using little-to-no proprietary software naturally led to questions about what software was actually worth. Cowen & Co. analyst Peter Goldmacher estimated in 2011, as an example, that Google-owned YouTube would have spent nearly six times as much building out its infrastructure on Oracle Exadata versus open source software and commodity hardware alternatives. But while Google was not built upon a model of monetizing software directly, as was Microsoft before it, its behavior suggests that the firm does believe software can still be differentiating. Instead of directly open sourcing pieces of its infrastructure like Dremel, Pregel, or Spanner, Google instead publishes publicly the details required to implement them, giving the community the opportunity to implement their own version, as it did with Hadoop following the Google Filesystem and MapReduce papers.

Amazon, though founded four years before Google in 1994, shares the search provider’s core philosophies in terms of the importance of open source code and the need to protect its own innovations. Amazon.com and its AWS subsidiary are voracious consumers of open source code, and have not only built their own infrastructure on top of it but created a line of business in Amazon Web Services to sell a set of services, all of which run on open source software on some level, to other companies. It is, however, very reluctant to disclose details in terms of its usage, and is not a major contributor to open source more broadly. From this, it is easy to conclude that the company believes that software innovation is still worth protecting. This semi-opaque model differentiates companies of this generation from the fourth, or current, generation of software creators.

- Fourth Generation (2004–present)

- Like Google, the group of Facebook, GitHub, LinkedIn, and Twitter are all principally built on open source software as opposed to proprietary alternatives, in large part because the economics of licensing software at extreme scale remain problematic. Unlike Google, however, Facebook, GitHub, LinkedIn, and Twitter tend to operate as if internally developed software is less of a differentiator or competitive advantage. Each has released sizable internally created projects as open source. GitHub founder Tom Preston-Werner summed up that company’s justifications in a 2011 piece, “Open Source (Almost) Everything,” detailing the perceived benefits of open sourcing noncore assets, which include better efficiency in hiring and retention, improvements in visibility, less duplication of effort, and more. What these and other justifications imply, however, is simple: in cases where source code does not represent a competitive advantage—which is most cases in most companies—the benefits of releasing source code far outweigh the costs of keeping it proprietary.

We have come full circle, in other words. Software, once an enabler rather than a product, is headed back in that direction. There are and will continue to be large software licensing revenue streams available, but traditional high margin, paid upfront pricing will become less dominant by the year, gradually giving way to alternative models we’ll discuss later in this book.