20. DIDDLING AD 1849

THE ORIGINAL CON MAN

No book dealing with frauds, fakes, and fallacies could avoid eventually mentioning the original confidence man, baptized with that title by the New York Herald back in 1849. The con man’s name was actually William Thompson, and by today’s standards, his scam was laughably simple. As the Herald put it, “He would go up to a perfect stranger in the street, and being a man of genteel appearance… would say after some little conversation, ‘have you confidence in me to trust me with your watch until tomorrow’… the stranger… supposing him to be some old acquaintance not at that moment recollected, allows him to take the watch.”

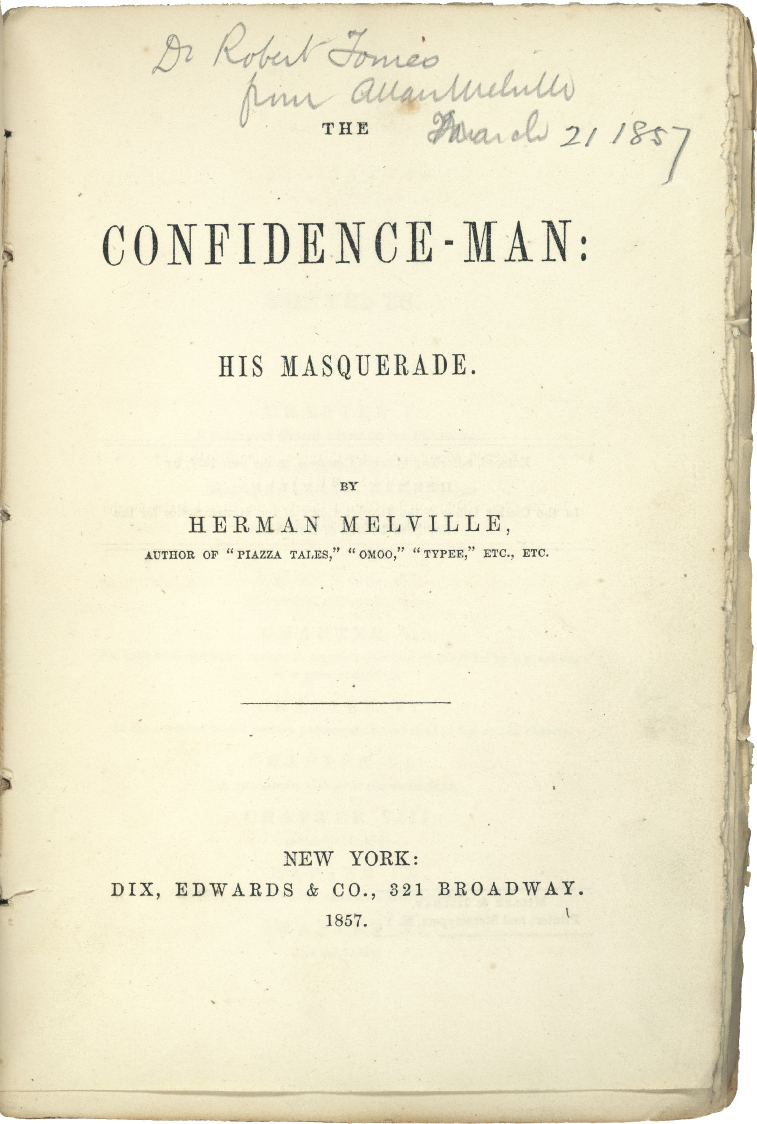

Herman Melville’s The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade borrowed its title from the headline of the New York Herald’s 1849 story about William Thompson. Set on a Mississippi steamboat on April Fool’s Day, Melville’s last novel satirized several nineteenth-century literary celebrities including Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Edgar Allan Poe.

One reader who was impressed by the Herald’s story of “The Arrest of the Confidence-Man” was Herman Melville, who went on to enshrine the profession’s newly acquired name in the title of his otherwise fairly unsuccessful novel The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade, published in 1857. Earlier in the nineteenth century, practitioners of the craft had often been known as “diddlers,” for the character Jeremy Diddler in James Kenney’s 1803 farce Raising the Wind; and their skills had already been subjected to literary scrutiny at the hands of no less than Edgar Allan Poe.

Poe clearly considered the practice of deception to be hard-wired into the human condition. Indeed, he not only went so far as to define “man… as an animal that diddles,” but also suggested that “had Plato but hit upon” this formulation after he had been reproached for defining humans as featherless bipeds, “he would have been spared the affront of the plucked chicken.”

It is hard to imagine anyone falling for William Thompson’s rather crude ploy today. Or is it? Maybe it was all in the performance, something that is hardly captured in the brusque newspaper report. After all, it is the job of the con man to conscript his mark into a conspiracy, or at least into an implicit mutual understanding of some kind. Over the years, the stories told by petty con artists have tended to become more elaborate; but in many ways the story itself is just the icing on the cake, or the means to the end; it is the relationship it helps create between fraudster and mark that is the critical thing.

Edgar Allan Poe, not above a good hoax himself (see chapter 18, Aerial Feats), understood that very well. In an 1843 essay, inspired by Kenney’s character and subtitled “Diddling Considered as One of the Exact Sciences,” he nailed the essential qualities of a successful diddler. These included what he called minuteness (keep the scale small—an injunction since widely honored in the breach); a keen sense of self-interest (to keep the conscience at bay); ingenuity and audacity; and perseverance, nonchalance, impertinence, and cheerfulness (all key elements in the performance). Despite his subtitle, Poe clearly considered diddling to be, in essence, one of the dramatic arts.

The most famous list of rules for successful con artistry, “Ten Commandments for Con Men,” is attributed to Victor Lustig, a polyglot Austrian who certainly knew what he was talking about. Knowing that the relationship between the scammer and the mark was the key to any successful fraud, Lustig framed his rules to apply to the performance, rather than to the product—though in his view, fast talking was for magicians, not for con men. Indeed, Lustig’s first two commandments are to be a patient listener, and to never look bored. He understood that any relationship is a two-way street, and his third and fourth rules involve taking note of the mark’s religious and political opinions, and agreeing with them. Most of the other commandments involved commonsense advice about appearance and demeanor.

Lustig is famous for selling fake money-printing machines to clients who were necessarily of questionable probity. But without doubt his greatest coup was selling the Eiffel Tower for scrap. The tower had been built specifically for the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris, and had been scheduled for dismantling in 1909; but in 1925 it was still there, and in fairly poor condition. Posing as a ministry official, Lustig invited six scrap metal dealers to submit bids, and selected one as the winning bidder.