22. ULTIMATE DIETS AD 1869

BREATHARIANISM

People in developed countries are obsessed with dieting. Mostly that is because we are anxious to lose excess weight, of which in modern economies there is a great deal around; and just how difficult this process turns out to be is evident in the soaring sales of largely unread (or unfollowed) diet books, and in the speed with which diet fads come and go.

Another major motive for eating a diet of a particular kind involves worrying about what exactly it is that one consumes. Reasons for such concerns are diverse. Some involve issues of principle and taste (with which there is famously no arguing). Others turn on questions of physiological appropriateness (though when it comes to diet humans are, like their ancient ancestors, the ultimate generalists, and nobody has been able to show that there is any such thing as an “optimal human diet”). And some people simply seem desperate to rid their bodies of “toxins.” In this last case, an uneasy relationship with the ultimate product of the alimentary canal seems to produce a yearning to empty the tract altogether, with the aim of eliminating from the shrine of the body anything that might be construed as impure.

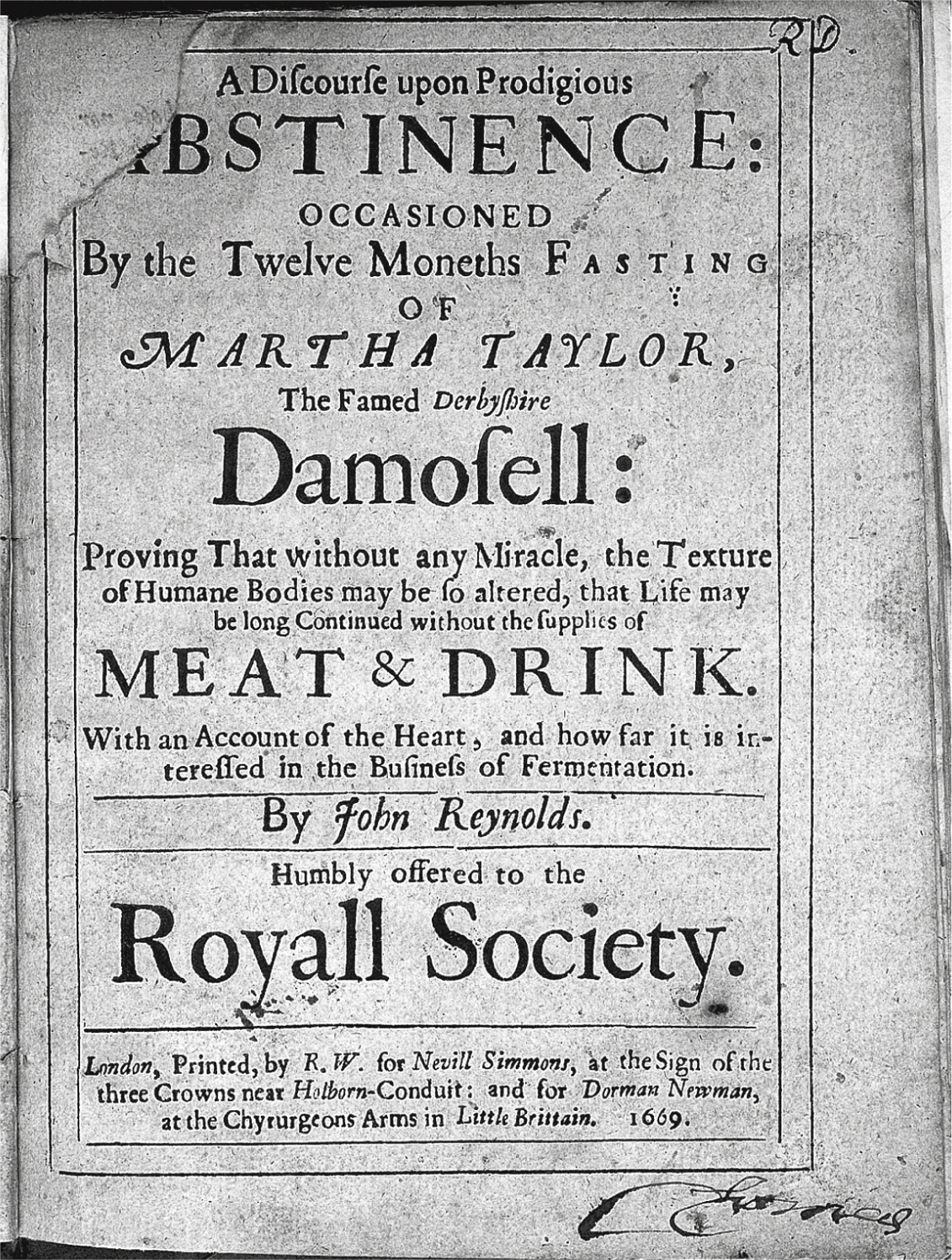

And then, of course, there are the breatharians. These are folks who, sometimes to fatal effect, have concluded that they can get by without eating at all—or who at least like to make other people think that they can. Over the years there have been enough of them to inspire a name for the state they aspire to: “inedia,” the ability to live without food. The story of inedia goes back at least to the sixth century BC Sanskrit compendium Sushruta Samhita, one of the foundational texts of Hindu medical practice.

The most celebrated nineteenth-century case of this curious condition was that of a Welsh child called Sarah Jacob, born in 1857. The story goes that, after health issues at the age of ten, the young Sarah lost her appetite and eventually gave up eating altogether. Her parents energetically publicized her “miraculous” ability to go without food, and the gaunt child eventually became a minor tourist attraction, and a source of substantial revenue for her family.

After a year or so of this, a committee was appointed to look into suspicions that Sarah might have been snacking on the quiet, and following two weeks of scanty surveillance, it reported that no cheating was involved. Sarah’s celebrity skyrocketed as a result, but substantial doubts nonetheless persisted. Accordingly, at the end of 1869 Sarah was checked into Guy’s Hospital in London to be watched continuously by a team of nurses. Soon the child grew weak, and her parents were urged to feed her. They refused, and after only eight days of fasting the poor Sarah died. Naturally enough, of starvation.

The public was outraged. Sarah’s parents were put on trial and were jailed following a verdict of criminal negligence. Not only science and common sense but also the courts had finally affirmed the amazing truth that people cannot go long without food. It is no coincidence that it was shortly after this episode, in 1873, that the renowned physician Sir William Gull first diagnosed anorexia nervosa as a pathological condition.

But of course, we are dealing here with Homo sapiens, and it is a well-known trait of members of that species never to learn from experience, especially that of others. Extreme fasting, recognized since antiquity as a method of attaining religious enlightenment, or at least as a fast track to hallucination, has been co-opted in the service of any number of bizarre belief systems. Among the most radical such expressions is the aforementioned breatharianism, named for the declaration, made in the early 1920s by the German Catholic nun Therese Neumann, that “one can live by the Holy Breath alone.” By any standard this was an immoderate formulation, eliminating water as well as food from the diet.

Since Therese survived to die of a heart attack in 1962, one might be forgiven for wondering if she actually practiced to the letter what she preached; nonetheless, according to an article in London’s Daily Mail, by 2007 the world had an estimated five thousand breatharians and “light nutritionists,” the latter imbibing the occasional glass of diluted fruit juice—strictly to eliminate toxins, you understand.

One of the most prominent breatharians of recent times was an Australian financial adviser named Ellen Greve—or, as she preferred to be known, Jasmuheen. She lectured worldwide on the subject and gained a quite extensive following. Rather embarrassingly, in the late 1990s a reporter discovered that her home refrigerator was packed with food (which she said was for her convicted fraudster husband); as a result, she was challenged by the Australian TV program 60 Minutes to prove that she could live for a mere week with no nutrients other than air.

After two days under medical supervision in a hotel room Jasmuheen began showing signs of physiological stress. Blaming this on polluted air from a nearby highway, she demanded a change of venue, to a remote mountainside. But her condition continued to deteriorate until the TV people discontinued the experiment after a total of four days, fearing for her life—although Jasmuheen claimed it was because they “feared it would be successful.” Sadly, not long afterward the starved and emaciated corpse of an Australian environmentalist called Verity Linn was found on a lakeside in Scotland. Her diary revealed her devotion to Jasmuheen’s teachings.