32. FAKE MUSIC AD 1913

FRITZ KREISLER

Music is almost certainly as old as humankind itself. A vulture-bone flute made more than forty thousand years ago is known from an Ice Age cave in Germany, but it’s just the earliest proof we currently have that people were making music back in the Old Stone Age. It’s a safe bet that the roots of music itself run much deeper in time.

For most of that long history, music presented rather strictly limited opportunities for fraud—although “faking it” as a musician’s technique certainly has a respectable history. But particularly once individual composers and performers had gained mass audiences through recordings and video, the calculation changed.

Fritz Kreisler is regarded as one of the greatest violin masters of all time. Known for his mellifluous tones and nuanced phrasing, he produced a sound that was immediately recognizable as his own. His 1920s performances of the Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Brahms violin concertos with the Berlin State Opera Orchestra are considered his finest. The two most popular compositions he wrote under his own name are “Liebesfreud” (“Love’s Joy”) and its companion “Liebesleid” (“Love’s Sorrow”).

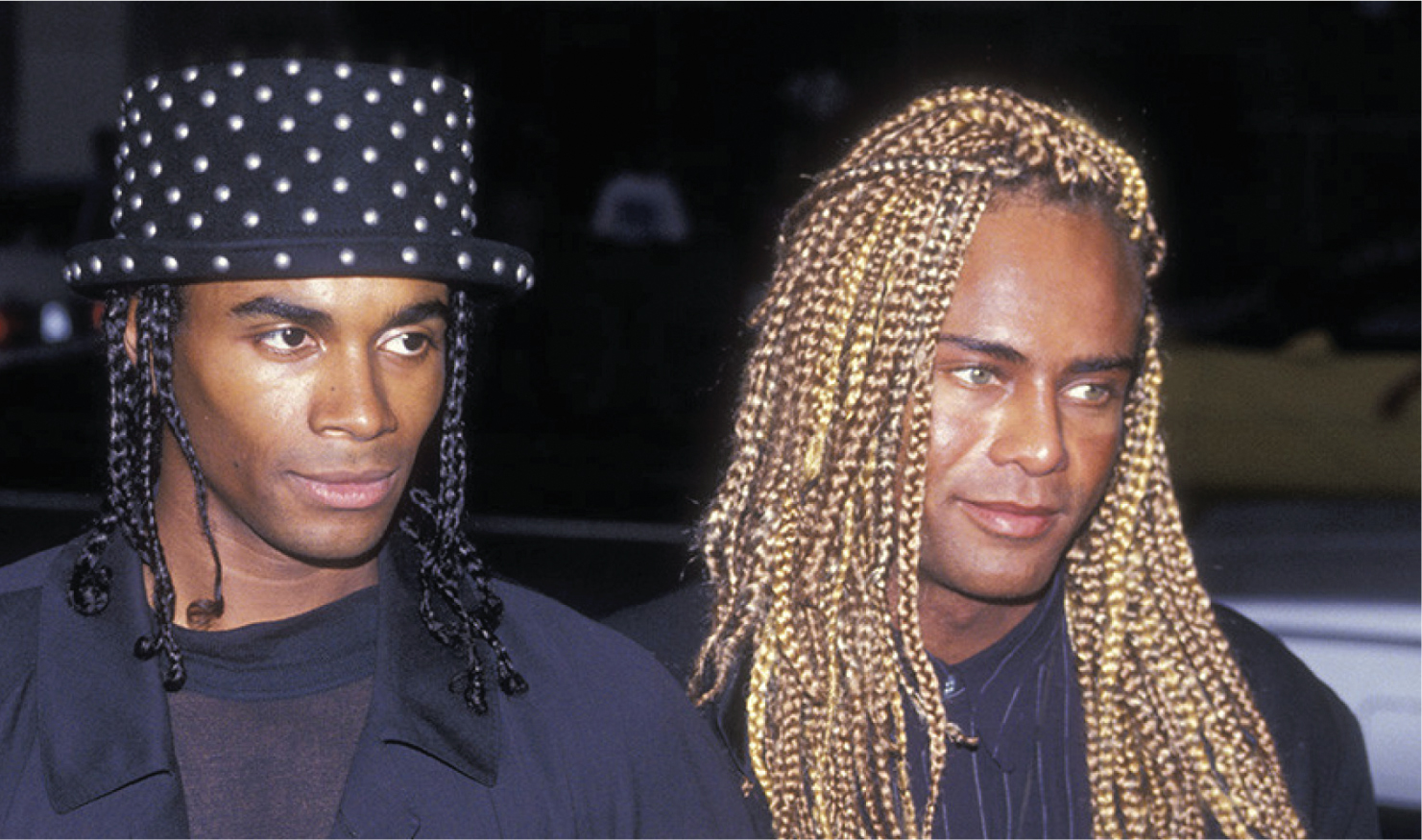

In 1990, the pop group Milli Vanilli was stripped of its Grammy award after it was revealed that frontmen Fab Morvan (left) and Rob Pilatus (right) had not sung on their hit album. On the eve of a 1998 comeback tour, Pilatus was found dead in a Frankfurt hotel room of a suspected alcohol and prescription drug overdose.

Musical frauds have been many and varied, though most have been of only parochial consequence. In the early nineteenth century, the Anglo-Polish musician Isaac Nathan published a series of traditional synagogue melodies that he improbably claimed to have been the same music that had been played in Solomon’s Temple in ancient Jerusalem. So convincingly did he argue this fraudulent attribution that the poet Lord Byron actually wrote English words to accompany Nathan’s music. Nathan himself went on to fight a duel over Byron’s mistress Lady Caroline Lamb, and ultimately emigrated to Australia, where he wrote and produced the first indigenous opera, performed in Sydney in 1847.

The most publicized musical fraud of recent years, if not necessarily the most noteworthy, was perpetrated by the German hip-hop funk duo Milli Vanilli, who turned out not to have actually sung any of the vocals on their hit debut album, allegedly at the insistence of their manager. When this relatively harmless deception came to light, the album’s Grammy was withdrawn, and the affair ended in tragedy when one of the musicians died of a drug overdose on the eve of a planned comeback tour.

On the classical front, a large number of recordings allegedly by an obscure and long-retired English pianist called Joyce Hatto famously appeared, to much critical acclaim, between 2003 and her death in 2008 at age seventy-seven. Eventually, these turned out to be digitally altered versions of recordings by other artists; and although Hatto’s husband insisted that she herself had not been knowingly complicit in the fraud, doubts persist.

As musicians themselves have become hugely commercially valuable properties, so have the instruments they play. In 2012 an Austrian court sentenced the well-known instrument dealer Dietmar Machold, formerly nicknamed “Mr. Stradivarius,” to six years in prison. Not only had Machold sold several inferior violins at vastly inflated prices as the products of the genius eighteenth-century Italian luthier Antonio Stradivari, but he had secured numerous large bank loans on instruments that belonged to clients, or that turned out not to be the work of the master.

Since Stradivari instruments have sold for close to $10 million (and up to $45 million has been asked for them at auction) it is hardly surprising that Machold is only the most recent of many Stradivarius forgers: while some 650 documented Stradivarius instruments of all kinds survive (violins, violas, cellos, and the occasional harp), there are many thousands of instruments out there that bear the Stradivari name.

But unquestionably the most genial deception in the history of music—or indeed, of practically anything else—was perpetrated in the early twentieth century by the Austrian virtuoso violinist Fritz Kreisler. Kreisler was a youthful prodigy who fizzled out on his first visit to the United States and almost became a painter instead. But music eventually won out, and in 1899 he made a triumphant reappearance on the American classical music scene. Audiences loved him, and, unusually, so did both the critics and his musical colleagues.

Still, the young violinist yearned not only to play but to compose as well. The problem was that, at the time, it was considered inappropriate for young performers to play their own pieces. Accordingly, after 1913 he began to “discover,” and then perform, lost masterpieces by famous composers such as Mendelssohn, Paganini, Vivaldi, and Couperin. These he had allegedly obtained by combing the ancient monastery libraries of Europe to unearth a continuous stream of forgotten and dusty old musical manuscripts by earlier masters.

Kreisler’s apparent luck in this quest was truly phenomenal, but for years nobody saw fit to question the authenticity of any of these discoveries. Partly this was because the music itself was so well written, and so much in character with the other output of those who had ostensibly written it. And partly it was because in the hands of Kreisler the music sounded wonderful. For although Kreisler had actually written all of those pieces himself, he was truly both a composer and a performer of distinction. The public was enthralled by the combined result, and Kreisler went on to be the most highly paid violinist of his day, commanding up to $3,000 for a single appearance.

A string of serendipitous discoveries of this kind was bound eventually to raise suspicion. In 1935, the New York Times music critic Olin Downes duly contrived to locate one of Kreisler’s original manuscripts, and it became obvious that the jig was up. Kreisler readily confessed, and a predictable scandal ensued. But it was a pretty good-natured scandal. Shock there might have been, but no horror. Nobody really wanted to see Kreisler brought down, both because he was so engaging personally and because his music was simply so good.

So good, indeed, that many of his pieces—both his forgeries, which usually appear in hyphenated form (e.g., “Dittersdorf-Kreisler, Scherzo”) and works that appeared under his own name—survive today in the repertoires of prominent contemporary violinists. Listen to them.

So great were Kreisler’s fame and the affection in which he was held that he easily weathered the controversy that erupted when in 1935 he admitted that the pieces he had performed as rediscovered works by earlier composers were, in fact, his own. As Kreisler remarked, “The name changes, the value remains.”