35. DIALECTICAL BIOLOGY AD 1938

LYSENKOISM AND ITS CONSEQUENCES

Evolutionary thinking began to emerge at the beginning of the nineteenth century, with the realization that the fossil record contains compelling evidence that life has changed over time. The very first scientist to articulate this recognition in a coherent way was Jean Baptiste Lamarck, in France. To account for the evolutionary changes he saw in the fossils he studied, in his 1809 Philosophie Zoologique Lamarck adopted the then-uncontroversial idea that individuals could pass along to their offspring characteristics that had been acquired over their lifetimes. For example, the theory went that giraffes had acquired their dominant feature gradually, as each generation stretched their necks out farther, striving to feed ever higher in the trees.

Although Lamarck was broadly right about evolutionary change, he was dead wrong about the mechanism that underlay it. Still, progress in the modern science of inheritance had to await a rebirth in 1900, when three groups of investigators independently “rediscovered” the rules of genetics that had been first articulated in an obscure journal by the Czech monk Gregor Mendel thirty-four years earlier.

Mendel’s main message had been that parental characteristics do not “blend” in the offspring. Instead, they are consistently transmitted in “particulate” form from one generation to the next. The grand discovery of the early twentieth century was that intergenerational changes came in the form of “mutations” that occurred randomly—as we now know, because of spontaneous changes that occur in the DNA. This view of heredity was eventually co-opted into the “new evolutionary synthesis,” which in the mid-twentieth century came to underpin our modern views of how evolution occurs.

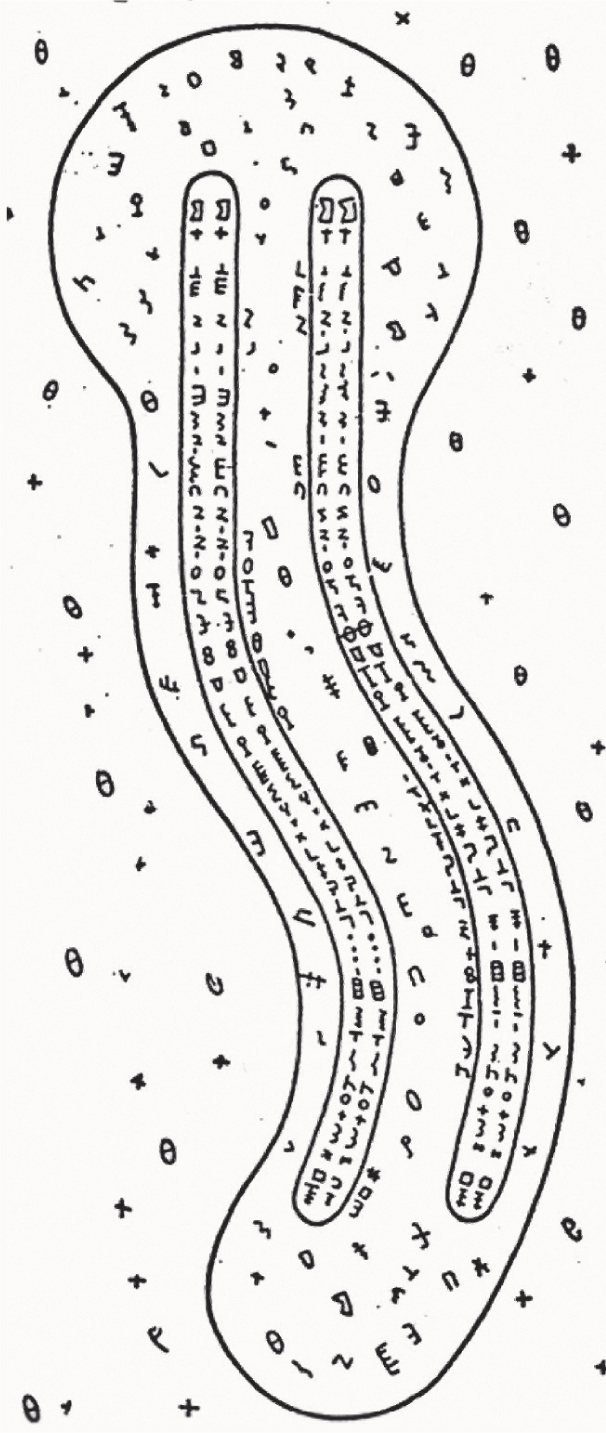

In 1927, Russian biologist and pioneer of modern genetics Nikolai Koltsov proposed that inherited traits are transmitted via a “giant hereditary molecule… made up of two mirror strands,” as pictured here. This prescient observation was confirmed more than twenty-five years later when James Watson and Francis Crick published their model of a double-stranded DNA helix. In 1939 Lysenko and his supporters condemned Koltsov for spreading “racial theories of fascists.” Koltsov died the next year, allegedly poisoned by the NKVD.

Meanwhile, though, an extremely unhappy episode in early genetics unfolded between 1905 and 1910, in the laboratory of the geneticist Paul Kammerer at the University of Vienna. Kammerer induced the common midwife toad, which usually bred on land, to breed in water. He then reported that, after a mere two generations, his male toads had developed black “nuptial pads” on their hind limbs, the better to grip their slippery mates. This innovation, he suggested, supported the Lamarckian view of change as the accumulation of novelties acquired during the lifetimes of individuals.

When the American Museum of Natural History’s G. Kingsley Noble showed in 1926 that the appearance of nuptial pads had been simulated by the injection of India ink, Kammerer shot himself. Whether he was the faker or, as he claimed, the unwitting victim of a hoax, still remains unclear.

But while Kammerer’s fate is the stuff of tragedy, it pales in comparison with what occurred in Russia between 1925 and 1965. Russia was an early center of innovation in the nascent science of genetics; indeed, as early as 1934, one Russian scientist, Nikolai Koltsov, had already speculated that traits were inherited via a “giant hereditary molecule” that was “made up of two mirror strands that would replicate… using each strand as a template.” He thereby anticipated by almost two decades the genomics revolution that was inaugurated in the early 1950s by the Watson-Crick discovery of the structure of DNA.

Science thrives on pluralist views, and in Russian genetics there was lively debate during the 1920s and 1930s between those who supported Mendelian ideas and those who clung to Lamarckism. Sadly, into this arena strode Trofim Lysenko, a plant breeder of humble origins who (falsely) claimed credit for developing a “cold treatment” whereby the time between the planting and harvesting of wheat could be reduced. This technique had been of particular value to politicians who were otherwise engaged in dramatically reducing the efficiency of the Soviet agricultural machine through collectivization, and it gave Lysenko huge political credibility. And, disastrously, Lysenko was a fervent advocate of something like Lamarckian heredity.

Trofim Lysenko (left) speaking at the Kremlin in 1935, with Josef Stalin (far right) who was the first to stand and shout, “Bravo, Comrade Lysenko. Bravo.” Center from left to right are Soviet Politburo members Stanislav Kosior, Anastas Mikoyan, and Andrey Andreyev. Forced collectivization under Kosior was the principal cause of the Ukrainian famine of 1932 to 1933. He was executed by Stalin’s order in the Great Purge of 1939. At the time, Kosior was first secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine. He was succeeded by Stalin’s successor Nikita Khrushchev, who eventually became the Soviet leader and was overthrown in 1964 partly due to his continued support of Lysenko.

By 1938 the wily and charismatic Lysenko had risen to the presidency of the powerful Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences; soon he also replaced the distinguished Nikolai Vavilov as director of the USSR Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Genetics. Lysenko’s rise to power was sponsored by Josef Stalin, who was obsessed with Lamarckianism. It was said that toward the end of his life Stalin’s only physical exercise came from trying to alter plants in greenhouses he had erected adjacent to his country dachas. When he failed to grow lemon trees in the Crimea, with its killing frosts, he unsuccessfully tried propagating oaks and other deciduous trees in the arid and salty steppes near the Caspian Sea, in the hopeless belief that they would adapt.

Lysenko never developed a scientifically coherent view of inheritance himself, but he nevertheless supervised the systematic suppression of mainstream (non-Lamarckian) genetic research in Russia. Numerous geneticists and evolutionists were incarcerated, or executed, or simply disappeared, while their work vanished from official records and textbooks. Koltsov was a particular target and mysteriously died in 1940, poisoned, it was rumored, by the secret police. Vavilov, renowned for his dedication to ending famine, and founder of the world’s most significant seed bank, starved to death in prison in 1943.

Backed by Stalin, and later by Nikita Khrushchev, Lysenko continued to wreak havoc on Soviet science until Khrushchev fell in 1964, following which he continued to live peacefully at his Gorki Leninskiye experimental farm until his natural death in 1976. But the most damning contemporary indictment of his career had already been published three decades earlier, penned by the distinguished American geneticist Hermann J. Muller. In an article baldly titled “The Destruction of Science in the USSR,” Muller wrote that “to a scientist, Lysenko’s writings are the merest drivel.”

And indeed, Lysenko could never have survived in a pluralist scientific environment in which ideas competed on merit. His success was entirely due to the backing of politicians who neither knew nor cared what made science tick, but who encouraged him to do irreparable damage to Russian science. This is something we would do well to remember in our own day, when science risks becoming something of a political football, and scientists themselves often find it easier to go to their congressman or senator for federal support than to risk the judgment of their peers in the national competition for funding.

Meanwhile, perhaps ironically, recent discoveries have brought to light natural mechanisms that might explain results of the general kind that Kammerer reported (though not, of course, the India ink). Water fleas, for example, may develop spiky (and hard-to-swallow) heads in the presence of a predator. Resulting from chemical signals emitted by the predator, this spiky feature may be passed to offspring because it is caused by alterations to the DNA that are stimulated by contact with the enemy.

Alterations of this kind are known as epigenetic, and they have nothing to do with the mechanism envisaged by Lamarck. Nor do they shed any doubt on the established principles of heredity. Yet, as Loren Graham points out in his 2016 book Lysenko’s Ghost, they have recently been seized on by scientifically illiterate Russian nationalists as evidence that the great Russian scientist Trofim Lysenko had been arbitrarily silenced by the power of Western propaganda. Once again, it appears, Russian science is under threat from politicians with agendas of their own. Today, Russia. Tomorrow, where else?