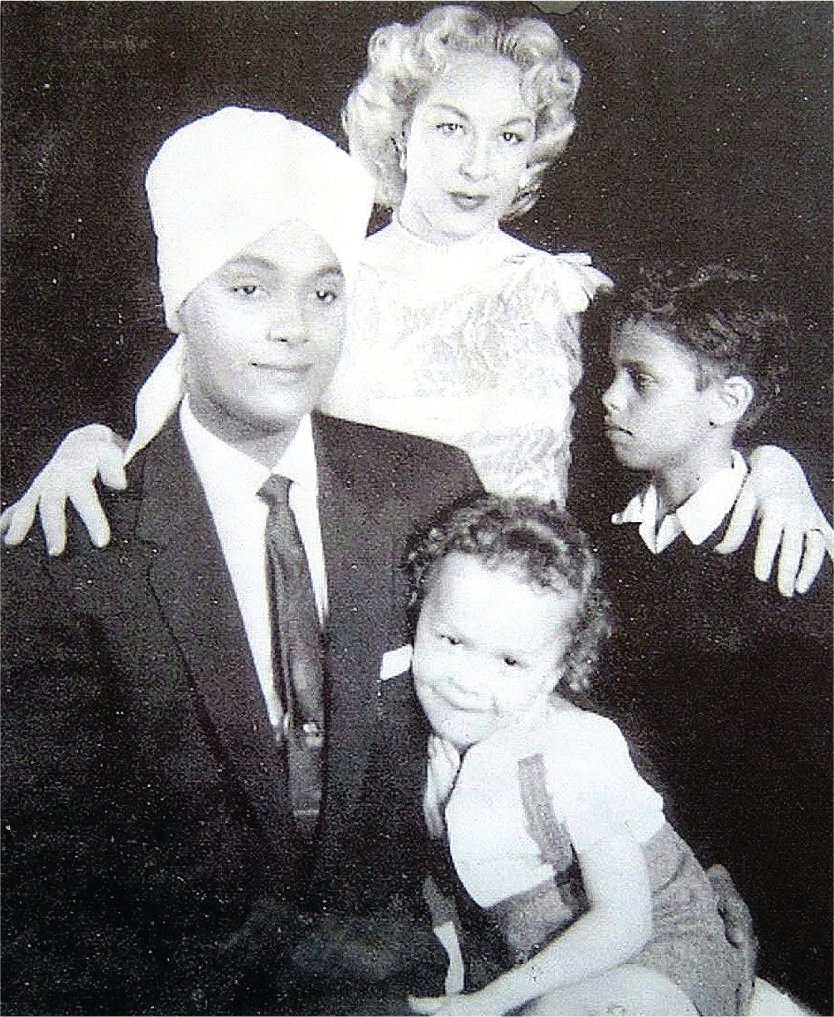

By this time Juan was working as staff organist for the Bakersfield radio station KPMC, while moonlighting for NBC in Hollywood and releasing his first recording in 1942 as an individual artist, a shellac disc called Right as the Rain. In 1944 he married his sister’s onetime roommate, the Euro-American Disney animator Beryl DeBeeson, who worked in the effects department of the Walt Disney Studio. Since interracial marriage was still illegal in California at the time, the ceremony was performed in Tijuana, Mexico.

It seems to have been his new wife’s idea that John/Juan should change his identity yet again. But this time, far from merely Hispanicizing his own name, he assumed an entirely different ethnic persona, and Korla Pandit was born. His name may have been inspired by that of Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, a well-known politician of the time who was the sister of India’s first prime minister and who had recently completed a highly publicized lecture tour in the United States. Korla Pandit’s biography gradually took shape as that of a piano prodigy born in New Delhi, India, to a French opera singer and a Brahmin father. As a child he had been sent to England to be educated, and then he had continued across the Atlantic to the University of Chicago, where he had trained as a classical musician and become acquainted with the pipe organ.

The identity makeover worked miraculously well. In 1948–49 Korla played Eastern-inflected organ music for an adventure-detective radio show called Chandu the Magician, and later that year he was offered a fifteen-minute daily television show of his own on KTLA, in which he did not speak but instead played the Hammond organ and a grand piano—often both at the same time—as he soulfully gazed into the camera.

Whether or not his silence was due to the difficulty of reproducing an Indian accent, the formula worked magnificently. Five days a week, the turbaned prodigy is said to have mesmerized a huge audience of mostly white housewives with that sensual gaze and spectacular keyboard playing. In all, some nine hundred episodes went out—a feat rarely matched in the years since. It is sad that very few of those live performances were recorded.

During the early 1950s Korla occasionally recorded with the Sons of the Pioneers, Roy Rogers’s original band, and began to release albums with Vita Records. This house was known as a “black artist” label, but Korla maintained his Indian identity and ultimately established his own label, India Records, moving later on to Fantasy Records.

By 1951 Korla had also begun working with Louis B. Snader, an entrepreneur who pioneered “telescriptions,” video recordings that were leased to TV stations nationwide as fill material, and that gave huge exposure to the artists who made them. In 1954 Snader signed him up for a series of fifty-two half-hour TV shows, but the terms of the contract were so onerous that Korla pulled out after having played the minimum number of performances. He was replaced by an unknown piano player who took over Korla’s set, piano, and decorations. The new pianist had only one name: Liberace. And at least part of the Liberace persona that emerged had already been preformed by Korla.

As time progressed, Korla’s style of music went out of fashion, although he experienced a brief revival in the 1990s with the reappearance of the tiki bar phenomenon. His last performance came in 1997, at the LunaPark club in Los Angeles, when his health was already in decline.

John Roland Redd’s whole life was spent as a performer. But maybe his most amazing performance of all took place behind the scenes: he maintained a close relationship with his family even as he became Juan Rolando and later Korla Pandit. This was unusual because, for fear of being outed, in the 1950s most light-skinned black performers who successfully “passed” did so at the cost of cutting ties to their family and their background.

Korla never abandoned his family, and, as the San Francisco Chronicle reporter Jessica Zack once mused, “living a lie on a daily basis must have been very difficult.” As she pointed out, “This wasn’t an act that occurred on stage for an hour or two, this was 24/7, all through his life. Korla put on this persona and couldn’t take it off.” Inevitably, all through this long saga plenty of insiders knew the true story. But out of respect for the extraordinary person that Korla was, nobody talked.

Of course, the exotic identity was only a small part of the tale. The main reason why the silent, hypnotic, and entirely invented Korla Pandit succeeded in being one of the most broadcast musical stars of all time was the most straightforward one of all. Like Psalmanazar (see chapter 11, Fraudulent Ethnicity) he was supremely good at what he did.