38. MISGUIDED ARCHAEOLOGY AD 1964

A LION IN WINTER

He was the world’s most famous paleoanthropologist, a weather-beaten fossil prospector famous for having discovered the world’s earliest artifacts and human fossils in his native Africa. Fifteen years his junior, she was a lively, ambitious archaeologist from western North America, a continent that almost all authorities still agree was uncontaminated by human beings until at most thirty thousand years before the present.

Excited by what she had found in the Calico Mountains region of California’s Mojave Desert, Ruth DeEtte “Dee” Simpson flew to England in 1959 to meet Louis Leakey, then visiting at London’s Natural History Museum. Clutched in her hand were some pieces of broken stone that she believed were tools that had been flaked by early Americans as much as 100,000 years ago. They looked unremarkable. But then, the very early artifacts that Leakey had found at Olduvai Gorge in what was then Tanganyika hadn’t looked like much, either.

Born in Kenya in 1903 to missionary parents, Louis Leakey had always plowed his own scientific furrow. He studied anthropology at Cambridge and soon began looking for ancient human fossils in his native East Africa, where he was convinced humankind had initially evolved. This conclusion ran directly counter to the prevailing scientific belief that Eurasia was the home continent of the hominid family; indeed, right around the time Leakey graduated, the anatomist Raymond Dart was running into firm establishment opposition to his announcement of the earliest “ape-man” fossil from his adopted country of South Africa.

A messy divorce soon put paid to Leakey’s prospects for advancement at Cambridge, and he became an independent Kenya-based operator for the remainder of his career. After exploring western Kenya for ancient ape fossils, Leakey and his new wife, Mary, had begun working seriously at Olduvai Gorge. There they found an abundance of early stone tools. These included large teardrop-shaped “handaxes,” like those long known from Europe; and in earlier deposits they found both simple stone flakes and the fist-size cobbles from which they had been knocked with a stone hammer.

Mary’s meticulous work convinced archaeologists that the unprepossessing flaked cobbles were indeed the earliest deliberately made stone tools. Since the existence of a tool implies a maker, the search was also on for the ancient hominids who had manufactured them. It took years, but in 1959 the Leakeys’ perseverance paid off with the discovery of the famous “Nutcracker Man” skull at Olduvai. Soon thereafter, Louis announced that his team had also found the more lightly built hominid fossils that he triumphantly named Homo habilis (“handy man”): the very earliest species of our own human genus, dated to about 1.8 million years ago.

These discoveries made the Leakeys instant scientific celebrities, and vindicated Louis’s longstanding faith in Africa as the cradle of humankind. They also evidently enhanced his conviction that what was important was to discover the “earliest” of everything. But his newfound fame also allowed Louis to promote his longtime interest in the study of living primates, which he saw as indispensable models for understanding the behavior of early humans. Notably, he was instrumental in making it possible—in a blaze of publicity—for three young women, Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Biruté Galdikas, to begin their studies of chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans, respectively.

Leakey’s weakness for attractive young ladies was hardly a secret, and when Dee Simpson appeared on the scene in 1959, the two instantly bonded over those stones from Calico. What’s more, back in 1929 Leakey had declared, in a Cambridge lecture, that people had settled in the New World at least 15,000 years ago. This was far earlier than was then believed, and he was not taken seriously; but now, thirty years later, he saw the chance to vindicate his pronouncement.

Much to the disgust of Mary, who was by now the preeminent authority on primitive stone tools and who harbored huge doubts about the geology of the site, Louis raised money for an archaeological prospection of the Calico Mountains. The National Geographic Society, which provided those funds to its superstar du jour, did so against the advice of Vance Haynes, its distinguished archaeological consultant.

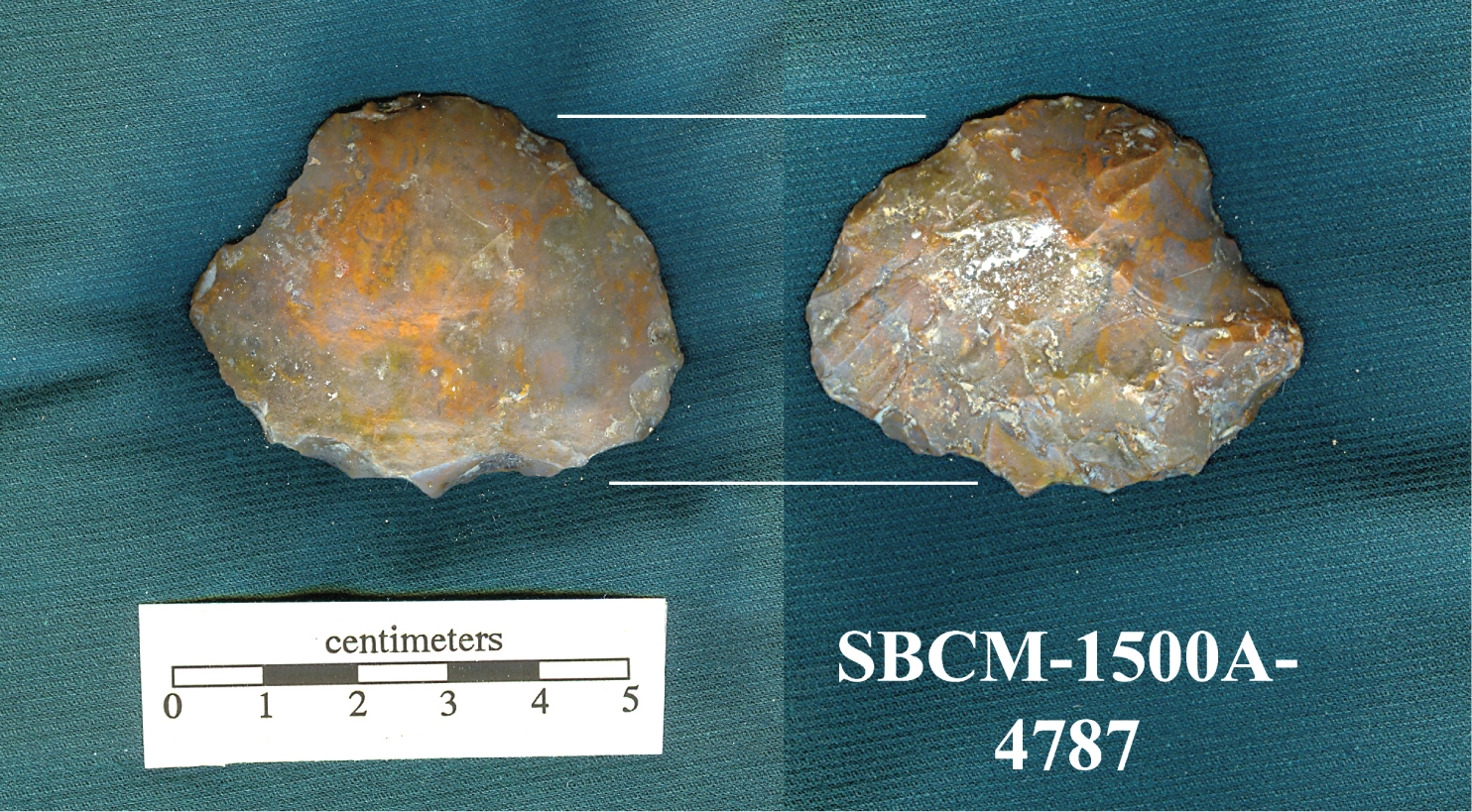

Little wonder, then, that excavations started, in 1964, in an atmosphere of general skepticism. Nevertheless, in 1968 Leakey and Simpson published a paper in the prestigious journal Science claiming that numerous stone flakes they had excavated at a new Calico Mountains site had been deliberately made by people, and were at least 50,000 years old (privately, Leakey guessed a lot more).

Almost nobody believed them then, and almost nobody believes them now. The most authoritative analysis of the Calico Hills “artifacts,” published by Vance Haynes in 1973, concluded that these alleged tools are actually ordinary stones that were fractured by being bashed together in a riverbed. In which case, the time at which they were deposited at the site—which still remains uncertain—is irrelevant to the early peopling of the Americas.

His long involvement in the Calico Mountains fiasco cost the ailing and aging Leakey much of his professional credibility, as well as his relationship with his wife, who had already begun to lead an increasingly separate life. As Mary tartly summarized the matter, Calico was “catastrophic” to Louis’s career, and “was largely responsible for our parting of the ways.” Dee Simpson, on the other hand, parlayed the Calico dig into a curatorship at the San Bernardino County Museum, where she remained until she retired in 1982, a decade after Louis’s death at the age of sixty-nine.

Louis Leakey was a powerfully instinctual man whose instincts had finally let him down, just as a lifetime of rugged tropical fieldwork had begun to take a serious toll on his body. Indeed, Mary strongly implied in her memoirs that his judgment was impaired by the physical pain of which he was rarely free after 1966. And that makes it even sadder to reflect that, had Louis stuck to his original intuition, he might be hailed today as mightily prescient. For at a time when most authorities reckoned the Americas had been colonized only around 2,000 years ago, Louis’s estimate of 15,000 years was remarkably close to the 13,000 years to which the Clovis, the earliest widespread and well-documented human culture in the Americas, is nowadays dated. Though there are now yet earlier contenders…