AD 1972 41. HUMAN VARIATION

THE FALLACY OF RACE

No term in our language is more divisive and misunderstood than the word race, or more redolent of a truly dark period in American history. But while many scientists nowadays argue that “race doesn’t exist,” the continued use of this tricky and ultimately unhelpful concept is constantly reinforced by a well-meaning government, every time a citizen is asked to classify him- or herself by ticking a box on a form.

Of course, the “race doesn’t exist” argument is, on the face of it, a highly counterintuitive one. Anyone walking down a street in a large American city will be instantly aware of just how heterogeneous the human population is. And that heterogeneity does indeed seem to be organized along broadly geographical lines: it is often not too difficult to guess if a some part of an individual’s ancestry lies in Africa, or in Europe, or in eastern Asia. This is because to the—very variable—extent to which such guesses are accurate, the perception of “race” does carry a historical echo.

Homo sapiens is a young species, born around 200,000 years ago. And it was less than 100,000 years ago that this species first left its African continent of origin and rapidly took over the entire world, displacing resident human species such as Homo neanderthalensis in the process. What this very recent origin and exodus clearly mean—and what the burgeoning science of genomics has equally eloquently demonstrated—is that the genetic variation we see among human beings today is very recent and very superficial indeed. There is greater genetic diversity found in three populations of central African chimpanzees than among humans worldwide.

While our newly born species was spreading across the globe, its members were itinerant hunters and gatherers. They moved, in small numbers, across vast tracts of landscape. In such demographic circumstances minor diversifications among local populations are highly likely to occur, whatever the species. And it was at this early stage of human history that people in different parts of the world acquired the minor physical features that tip us off today to geographical origin.

Some of those differentiating features had significant consequences: for example the ability, typical of cow-herding peoples, to tolerate lactose as adults and thus to subsist on dairy products. Others—probably most—were simply random variations, without much if any functional significance. Because evolution is not, as is often assumed, a process of single-minded adaptation and optimization, chance has played a large role in our coming to be as we are.

But even after people had become established in all the habitable zones of the world, the human population continued to grow. And that growth really took off after the origin of settled existence and agriculture (independently in several different places around the world) about ten thousand years ago.

Hunter-gatherers do not live in great density, but farmers need labor to till the fields, and sedentary mothers can cope with more children at once. The new settled way of life changed the entire human demographic dynamic, initiating a population explosion in the course of which, instead of acquiring their own minor local peculiarities, the expanding local populations began reproducing and blending with their neighbors, blurring genetic and physical differentiations.

What we see today, in a world of unparalleled individual and population mobility, is the result of a long and ongoing process of blending and blurring that has ensured the absence of any fixed lines to be drawn, anywhere within the human population. This is why many scientists maintain that races don’t exist, because you cannot define an entity that has no discernible boundaries.

In 1972 the Harvard geneticist Richard Lewontin looked at the genetic variation seen in human populations from around the world and concluded that some 85 percent of that variation existed within local populations, and only some 15 percent between them. In other words, the heterogeneity within local groups—even groups you might in some way view as “racial”—is hugely larger than the genetic differentiation among them. The general pattern of differentiation that Lewontin saw has held up well as vast amounts of genomic information have poured in from all over the world, shedding yet more doubt on the utility—or even the possibility—of recognizing “races.”

The human genome is a fantastically complicated thing, containing 3 billion different bits of information. All these data encode a lot of historical information about each individual, and about the movement of people around the globe from which each of us has ultimately resulted. And analyzing the genomes of people in different countries has produced some very unexpected results. The supposedly homogeneous people of Iceland have turned out to have a suspicious amount of Scottish in their ancestry, for instance; and rarely does anyone submit a DNA sample to the Genographic Project or to the ancestry company 23andMe without getting at least a minor surprise.

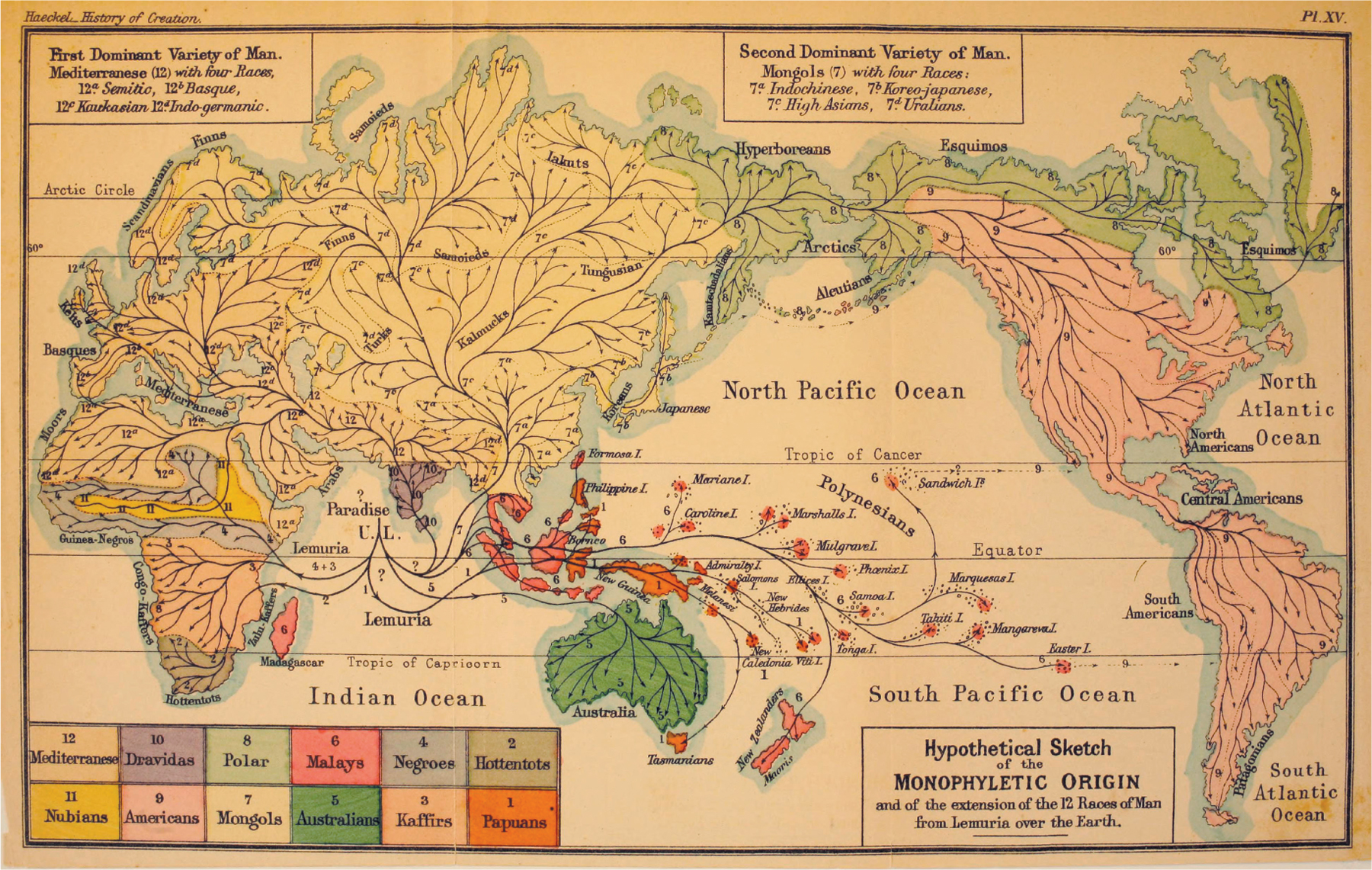

A map of the four major geographic groups of Homo sapiens. Africans are represented by yellow, Australians by red, and Europeans by green. Asians, in blue, exhibit some similarities with Europeans on one side (a light yellowish green tinge in the middle of Siberia) and with Australians on the other side. The extensive gradients due to admixture between Africans and Europeans in both North America and North Africa, and between Europeans and Asians in Central Asia, are clearly visible.

So what we are genetically, and what family tradition tells us we are, are often quite different. Maybe that’s not too surprising, because genes are biologically measurable entities, while identities are matters of human belief. And it is this reality that underlies the most important thing of all about the notion of race: that (to the extent to which it is useful at all) it should never be confused with cultural identity. Because from whatever background he or she comes, each new human is born into this world with the potential to absorb any language, or any set of cultural beliefs, that humanity has yet devised.

On the other hand, by the time they are six years old—maybe earlier—participants in different human cultures have already absorbed preconceptions and values that may mean they are living in perceptually different worlds from their peers raised elsewhere. And on a rapidly globalizing planet this is, of course, a major source of potential—and actual—conflict. Whatever our geographical origins, it is our cultures that most fundamentally determine our identities. Today we are, above all, who we think we are.