AD 1976 42. ETERNAL LIFE

THE FROZEN SELF

In the basement of New York City’s American Museum of Natural History is a spotlessly clean room packed with large stainless steel vats. Open one and a freezing cloud of liquid nitrogen rises to greet you. Inside you will find, carefully packaged and identified, tissue samples taken from individuals belonging to a huge array of animal species. Most importantly, they harbor the DNA of each species represented; and since it has become possible to rapidly and inexpensively sequence the long DNA molecule, DNA has become a vital tool in scientists’ quest to figure out exactly where each species stands in the great tree of life to which we all belong.

The Ambrose Monell Collection is an innovative expression of biological cryogenics, a field that seeks to preserve living tissues through maintaining them at extremely low temperatures. Other biological uses of cryogenic technology include the freezing of sperm, ova, and embryos for future reproduction, and various applications in transplant surgery and emergency medicine.

One extraordinary natural experiment in biological cryogenics occurred in 1986 when a Salt Lake City toddler named Michelle Funk fell into a freezing mountain stream, in which she lay submerged for more than an hour. Although she didn’t have a pulse and was not breathing when she was found and rushed to a hospital, doctors using a heart-lung bypass machine were able to warm her body; and once her internal temperature had risen to about 77°F, her heart spontaneously began pumping and she started to breathe again.

Within a couple of years, Michelle was once more a normally developing child. Her physicians surmised that her brain had been cooled so rapidly that it had immediately lost its need for oxygen; and during the entire sixty-six minutes of her immersion her bodily functions had apparently halted completely, obviating brain and other tissue damage.

By the time this incident occurred, the notion of preserving the human body through freezing was already well established in some circles. In 1962 the physicist Robert Ettinger had published a book called The Prospect of Immortality, the founding document of a field that has come to be known as cryonics.

Impressed by rapid advances in medical technology, but worried that by the time he died science would not yet have found a cure for the disease that would carry him away, Ettinger imagined being deep-frozen after his death and revived when a cure for his malady (and freezing) had been found.

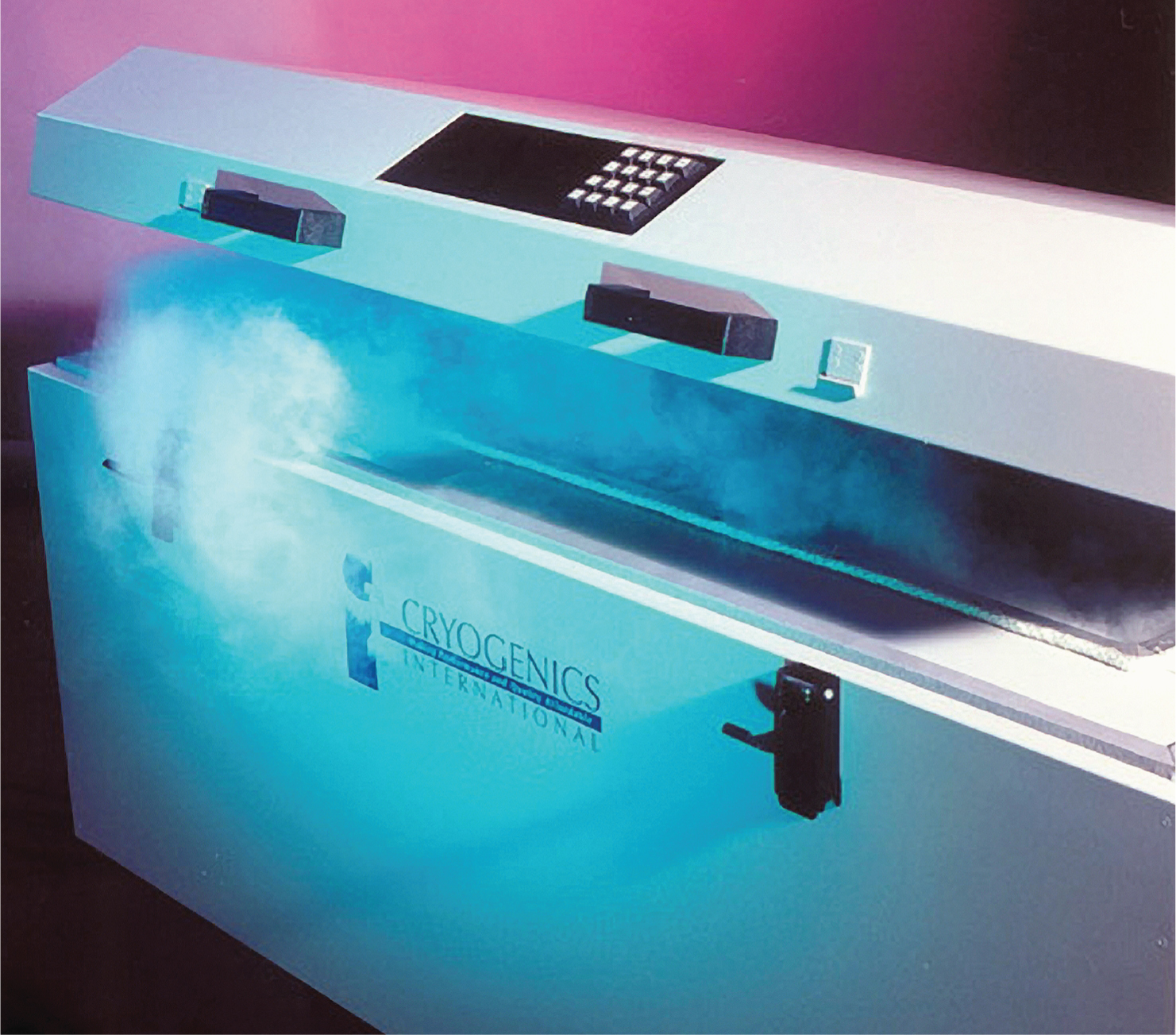

“Dewar” tanks are used to store cryopreserved bodies using liquid nitrogen. At room temperature, nitrogen is a transparent, odorless gas that makes up about 78 percent of Earth’s atmosphere. At −320° F it becomes a clear colorless liquid that is used by biologists to preserve blood, reproductive cells (eggs and sperm), and tissues, and by the cryonics industry to preserve clinically dead human bodies for possible future revival.

The fallacy was obvious: freezing tissues (as opposed to cooling them) causes irreversible changes, and restoring a frozen body—especially a dead one—to normal function is something nobody has the slightest idea how to do yet. No matter; Ettinger established a company to carry out his vision. And such is some people’s faith in the march of technology that in 1967 he deep-froze his first client, a University of California psychologist named James Bedford, in a vat of liquid nitrogen (from which he was moved to more state-of-the-art accommodations in 1991).

One of the issues here, of course, is that you cannot be frozen until you are legally dead. And death is, well, final. But the cryonics experts get around this by defining death as a process, rather than as an event: a process that is complete only when all the information encoded in the brain has been lost.

What is more, it turned out on further thought that, since personhood and all that goes along with it is the emergent product of each individual’s brain, all you really need to confer immortality to the person is to preserve the brain itself, usually conveniently housed within a head. And heads, of course, take up a lot less room in cryogenic “dewar” tanks than whole bodies do.

As to the technology itself, normal freezing tends to damage tissues through ice crystal formation in the water lying between the cells. Cryonics technicians who acoustically monitored heads as they were cooled apparently detected sounds that they attributed to microfracturing of the tissues; and although the investigators concluded that this microfracturing does not happen at the favored temperature of–140°C, this temperature is considerably above that of liquid nitrogen, the cheapest extreme coolant, making the necessary equipment—and the procedure—much more complicated and expensive.

But “cryopreservation” doesn’t stop there. “Cryoprotectant” chemicals can also be used to prevent mechanical cell damage, although returning tissues to proper function after they have been stabilized in this way is another story. The latest wrinkle is “vitrification,” whereby infusion of the tissues with special cryoprotectants (aka “antifreeze”), combined with slow cooling, converts the organ or body involved to a stable “glass-like” state. A rabbit brain was recently vitrified in this way, and its tissues reportedly looked entirely normal when thawed and examined microscopically. How well it would have worked if restored to its original owner is, of course, something else entirely.

Plan on spending a large chunk of change if you are considering any of this. Three commercial outfits offer the service in the United States, and one in Russia; charges vary. The all-in luxury model will set you back over $200,000, with annual maintenance charges extra; some clients have elected to finance these fees through life insurance (with the cryonics folks as beneficiaries, of course). A bare-bones procedure, if you’ll excuse the expression, is $35,000, on top of which you’ll have to pay for your own expensive transportation to the preservation site. If you elect to have just your brain preserved, a leading facility is currently quoting around $80,000.

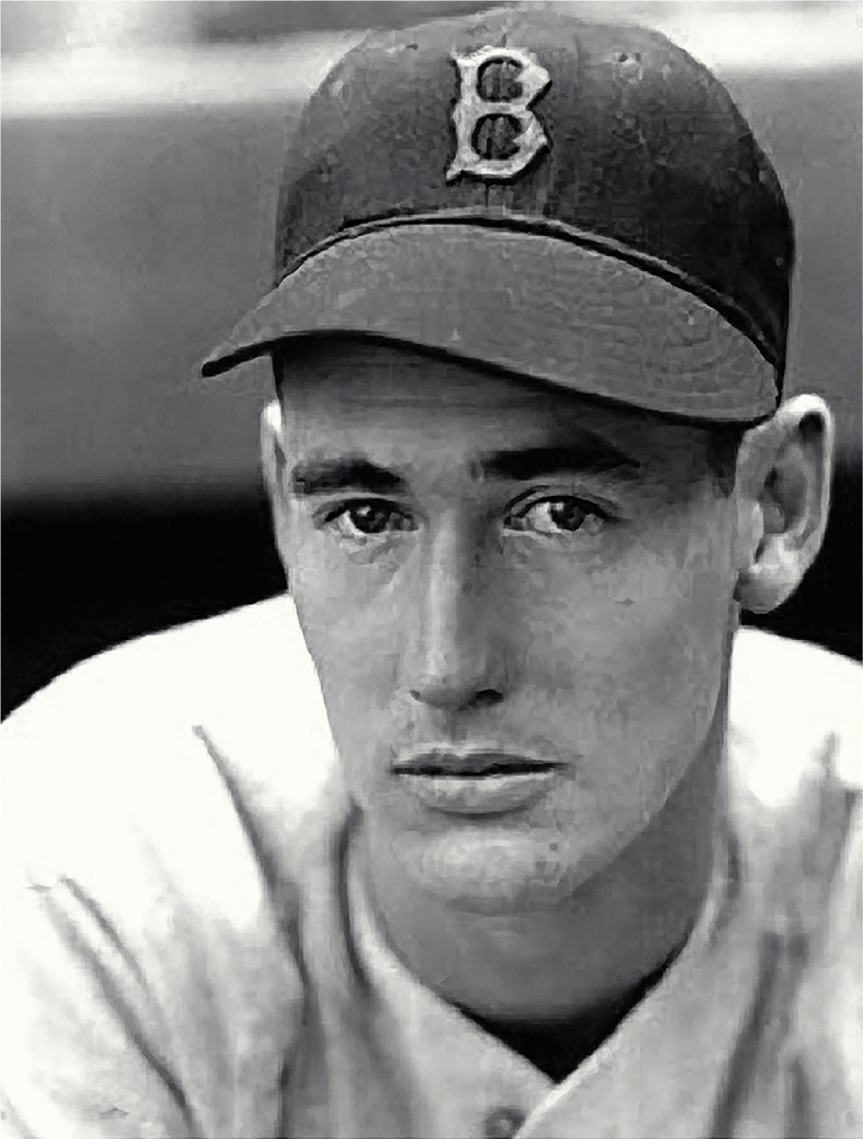

When in 2002 baseball Hall-of-Famer Ted Williams died, his head was cryopreserved. In the years that followed his frozen head became the subject of acrimonious legal disputes between his son John Henry and other members of the family, including claims that it allegedly had been mistreated by the company preserving the head.

To date, nearly three hundred people have been cryopreserved in the United States. The most famous of these is the baseball player Ted Williams (contrary to rumor, Walt Disney was not frozen). Timothy Leary almost signed up but begged off, saying that the cryonics people “have no sense of humor.” Nonetheless, some 1,500 other hopefuls have apparently already ponied up for the service, and are waiting in the wings.

Exactly how and under what circumstances the thawing of human bodies would be done remains conjectural, and for the moment the chances it could ever be done successfully look pretty dim at best. And whether the world you or your shade wake up in will be one you could in any way relate to is, of course, just as uncertain. Guaranteed, though, you’d have a tougher time than Woody Allen in Sleeper.

Finally, the mainstream Cryogenic Society of America, obviously embarrassed by its similarity in name to something it considers entirely disreputable, makes a point of saying this about cryonics on its website: “We do NOT endorse this belief, and indeed find it untenable.” Better to spend your money on something you know will make you happy while you know you can enjoy it.