43. HOMEOPATHY AD 1988

THE MEMORY OF WATER

Homeopathic medicine has a long pedigree. Some trace it all the way back to the fifth-century BC physician Hippocrates, who is said to have prescribed small doses of mandrake root to cure psychoses resembling those caused by larger doses of the stuff. Others look to the sixteenth-century physician and alchemist Paracelsus, who believed that “what makes a man ill also cures him.” But in its modern form homeopathy emerged around the turn of the nineteenth century, when it was promoted by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann as an alternative to the (admittedly rather barbaric) mainstream medical practices of his time. It has since become a multibillion-dollar business.

Practitioners who followed Paracelsus and his “like cures like” formula (give extract of onion for curing colds’ running noses, for example) rapidly discovered that many of the supposedly healing animal, vegetal, and mineral substances they prescribed their patients were actually toxic in large doses. It therefore became customary to dilute such substances with water.

Hahnemann’s contribution was to systematize that dilution process, and to test its application in the treatment of numerous different conditions—with results that have since been widely disputed. The dilution was typically accomplished by violently shaking the solution and by knocking its container against a hard surface—a part of the process that came to be regarded as of particular importance.

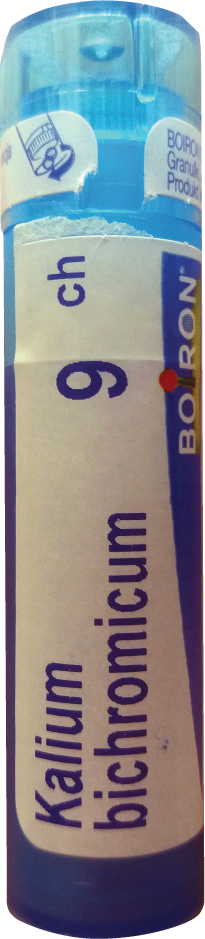

Kalium bichromicum (bichromate of potash) is a homeopathic remedy recommended for treatment of maladies of the mucous membranes. It is usually prescribed at 30C, which means the compound has been diluted to the equivalent of one molecule in all the oceans of the world combined. The FTC has recently mandated that marketing claims made for over-the-counter homeopathic drugs must meet the same standards as those for other medicines.

Today, following Hahnemann’s precedent, the accepted unit of dilution is known as C (one unit in a hundred), and the dilution is typically done repeatedly. One drop in one hundred, diluted six times, gives you the equivalent of one drop in a couple of Olympic-size swimming pools; twelve repeats corresponds to one drop in the entire Atlantic Ocean. Any higher than 12C, and the probability is negligible that even one molecule of the supposedly curative substance will remain in a sample of any reasonable size. Yet 30C—far less than one drop in all the oceans of the world—is not unusual in modern homeopathic preparations.

No wonder, then, that modern scientists are skeptical of homeopathic medicine. For if the chances are that there is not even one molecule of the supposedly curative substance present in it, how can the medicine possibly work?

One obvious possibility is the placebo effect, whereby patients’ belief that they are being treated with something effective actually has a beneficial effect on their condition. When tested in clinical trials against bona fide medicines that looked identical, placebos—sugar pills are the favorite—have been shown to have some effect.

What’s more, the more powerful the belief, the more powerful is the apparent effect—which is why large colored pills are more efficacious than small white ones. Exactly how the placebo effect works is not fully understood, though one plausible suggestion is that a psychogenic reduction of stress hormones leads to a general improvement in patients’ health.

But with none of the supposedly curative agent present, there was no known way in which any homeopathic medicine could by itself have any effect, aside from whatever might have been derived purely from patients’ belief in it. So imagine scientists’ surprise in 1988, when a team led by the French biologist Jacques Benveniste published a paper in the prestigious journal Nature that claimed to have demonstrated the efficacy of a homeopathic preparation.

In that article Benveniste and colleagues claimed that the human white blood cells known as basophils changed their properties when exposed to vigorously shaken dilutes of antibodies that, by their own calculation, could have contained none of the original molecules. The diluting fluid itself apparently somehow retained a “memory” of the product that was no longer present.

Because of the controversial nature of this conclusion, Nature sent a team to Benveniste’s lab to investigate. The investigators included the magician and professional skeptic James Randi, and they came away unimpressed by the lab’s sample control. They concluded that the Benveniste group’s findings had been affected by “unintentional bias,” and labeled its results a “delusion.”

Undeterred, in 1997 Benveniste further boggled the minds of his fellow biologists by claiming that the effects of water memory—caused by an “electromagnetic imprint” in the fluid—could be transmitted over phone lines (the Internet was later added). This upset a lot of physicists (though one radical Nobelist rallied to his support), even as biologists in other labs were unable to reproduce his results.

In 1999 the pharmacologist Madeleine Ennis and several colleagues reported experiments showing that super-dilute histamines did inhibit basophil activity, and the fuss started afresh. Randi promptly offered a prize of $1 million to anyone who could replicate Ennis’s findings, and the gauntlet was picked up by the BBC TV program Horizon, which gathered an all-star team of scientists to replicate the Ennis experiments under the auspices of the august Royal Society.

With Randi in attendance, two separate laboratories followed an elaborate double-blind procedure in which the effects on basophils of extreme histamine dilutions were compared with those of samples of pure water. Only after the end of the trial did any of the participants know which samples were dilutes and which were controls. To cut a long story short, in the end Randi kept his million dollars. No replicable effects could be demonstrated, and variations among the samples in their effect on the basophils were no greater than would be expected by pure chance.

Even after all this, for some observers the case for water memory was not definitively closed. As recently as 2010 Ennis wrote—in a homeopathy journal—that to clarify the (inevitable) slight variations to be expected in smaller-scale experiments, an expensive and rigorously designed “multi-centre trial” was still required. Water memory has no known physical basis, but apparently it is a hard idea for some folks to let go of. And given the complexities of human belief mechanisms, there is little doubt that, as Ennis herself put it, this will be a “never-ending story.”

But maybe it shouldn’t be. In 2015 the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia published a comprehensive report in which more than 1,800 studies on homeopathy were scrutinized. Of these, it found that a paltry 225 were rigorous enough to be worth a closer look. And when it examined those better studies in detail, it discovered “no good quality evidence to support the claim that homeopathy is effective in treating health conditions.” Even more emphatically, the report’s authors recommend that “homeopathy should not be used to treat health conditions that are chronic, serious, or could become serious” (emphasis ours). Apparently, water does forget.