AD 2003 50. FAKE JOURNALISM

STEPHEN GLASS, JAYSON BLAIR, AND THEIR LEGACY

Jayson Blair was an American success story. Only the second African American to have edited the University of Maryland’s prestigious student newspaper Diamondback, by the tender age of twenty-four he had risen from lowly intern to staff writer on the national desk at the New York Times. A hugely prolific journalist, he authored hundreds of articles during his nearly four years writing for the Times, covering subjects as diverse as the problems faced by wounded veterans, the Washington sniper murders, and scares about anthrax. Although not universally liked by his colleagues, and distrusted by a few, the ambitious and garrulous Blair seemed set for a rapid rise through the ranks at the nation’s premier newspaper.

Then the blow fell. In April 2003 the San Antonio Express-News notified the Times that a story Blair had allegedly filed from Los Fresnos, Texas, had largely been lifted from its pages. That set in motion an inquiry that ultimately revealed a pattern of erratic behavior and inaccurate reporting going back right to his Diamondback days. Even then, writing about the university’s football team, Blair had embroidered stories with colorful quotes nobody had ever said, and as a manager of the paper he was a disaster, missing production deadlines and causing many of his coeditors to quit. When he himself prematurely stepped down as editor in chief, his successor actually issued an apology for the “speculative” reporting that had been published on Blair’s watch.

With a record like this, it seems remarkable in retrospect that Blair was able to get a job as a journalist anywhere, let alone at the nation’s leading newspaper. But editors were impressed by his ambition and productivity, and by the Times’s own account they accordingly ignored reservations expressed by his reporter colleagues. Still, direct accusations from a sister journal could not be ignored, and within a month of the initial allegation the Times publicly admitted that Blair had indeed consistently “misled readers and Times colleagues with dispatches that purported to be from Maryland, Texas, and other states, when often he was far away, in New York. He fabricated comments. He concocted scenes. He lifted material from other newspapers and wire services. He selected details from photographs to create the impression he had been somewhere, or seen someone, when he had not.” Blair was abruptly out, and disappeared briefly from view.

Blair himself was only one reporter of almost four hundred at the Times, and the stories he wrote tended to be of the human interest variety, rather than dealing with significant matters directly affecting public opinion. And the Times acted swiftly once the people at the top became aware of the problem. But journalism depends vitally on trust, and the episode severely eroded public trust in the Times—and the Times’s trust in itself.

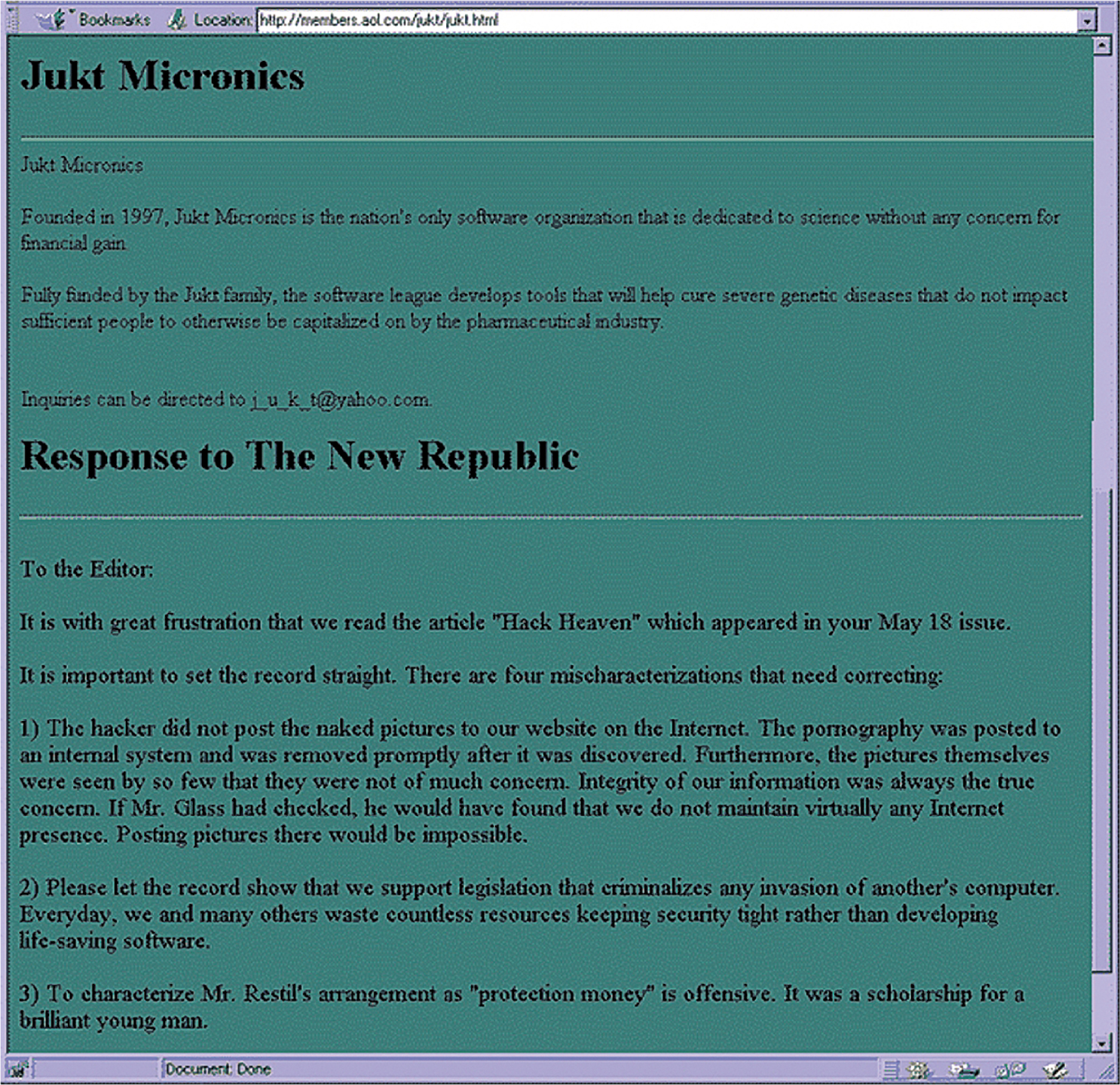

Of course, shady journalism was nothing new (see chapter 18, Aerial Feats), but public trust in journalists had actually been on particularly shaky ground since the revelation in 1998 that Stephen Glass, an associate editor at the New Republic, had fabricated around two-thirds of the articles he had written for the respected magazine. And it was rocked again when, right after the Blair scandal had broken, a team of journalists at USA Today “found strong evidence” that Jack Kelley, one of the newspaper’s star reporters—and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2002—had “fabricated substantial portions of at least eight major stories, lifted nearly two dozen quotes or other material from competing publications, lied in speeches he gave for the newspaper and conspired to mislead those investigating his work.” This revelation was particularly devastating because, unlike Blair’s, Kelley’s earlier career had produced no telltale signs for his superiors to ignore. Having developed a sterling reputation, Kelley was able to get away for years with writing about places he did not know, making up quotes by people he had never interviewed, lifting quotes from the work of others, and inventing “informants.”

Little wonder, then, that public trust in the journalistic profession—one of the primary guarantors of social and political freedom in our society—has sunk to historic lows in the first part of the twentieth century. In 2015 the polling organization Gallup found that trust in the news media was at one of its lowest points since surveyors had begun asking about respondents’ opinions on this subject more than forty years earlier.

And yet, at the same time it seems that the public not only cannot get enough of fake news but is eager to believe it (see chapter 25, Public Credulity). The Weekly World News flourished for a long time, and the National Enquirer is still a staple at supermarket checkouts; both stand as proof of the seductive nature of “infotainment.” Nonetheless, the 2016 U.S. presidential election saw an unprecedented proliferation of entirely fictitious “news” reports. These originated mostly on dubious websites, but many of them eventually made it into more mainstream print media as well.

In one small town in the remote and impoverished Republic of Macedonia, a virtual industry of teenage news faking developed, using dozens of bogus websites whose sole aim was to make their untruthful and sensationalist stories go viral. In a society where the average wage is $4,800 per year, one youthful news faker is said to have earned $60,000 from penny-per-click sites targeting American voters during the presidential campaign.

Indeed, the problem of fake news on the Internet has become so acute that in late 2016 both Facebook (through which much of it is disseminated) and Google announced measures to suppress the sites on which it originates. What’s more, at around the same time, Indiana University’s Network Science Institute announced the availability of a beta version of Hoaxy, a platform that is specifically designed to track the spread of phony news across social media.

This proliferation occurs in some remarkable ways. Take, for example, the apparently widely believed “Pizzagate” story, which had Hillary Clinton and her campaign chairman John Podesta running a pedophilia ring out of a Washington pizzeria. Eventually a (real) gunman showed up at the restaurant and began firing at random. And although he subsequently admitted to the New York Times that “the intel on this wasn’t 100 percent,” that did not prevent a search on Hoaxy for this classic false-news episode from turning up a further twenty fake stories on it!

Ultimately, though, the more important problem lies not on the supply side, but on the demand one. The despised established media are, in fact, pretty vigilant about policing the material they place before us, and every time a member of the public rejects them in favor of believing and propagating phony and often entirely misleading “news” stories on social media or anywhere else, our corporate grip on reality slips a little more.

This slippage is even more alarming when it is led from the top. In an age when the U.S. President with “the biggest inauguration crowd ever” denounces the mainstream media as peddlers of fake news, and excoriates the press indiscriminately as the enemy of the people, it seems that all bets in the domain of public information are off.

On October 30, 2016, a white supremacist Twitter feed claimed there was an international pedophilia ring linked to members of the Democratic Party. Spreading like wildfire on social media, alternative news websites, and talk radio shows, this initial claim quickly morphed into a full-blown conspiracy theory that involved coded messages, satanic rituals, and a Washington D.C. pizza parlor harboring child sex slaves. Five weeks later, a man fired three shots into the restaurant.