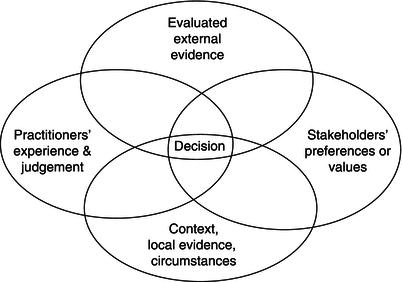

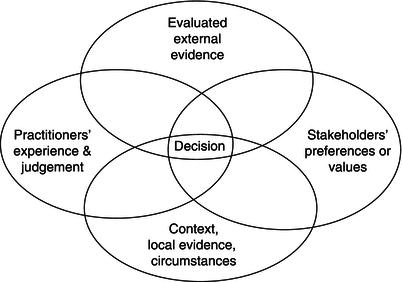

Figure 3.1 The elements of evidence-based practice (adapted from Briner et al., 2009).

Briner, R. B., Denyer, D., & Rousseau, D. M. (2009). Evidence-based management: Concept cleanup time? Academy of Management Perspectives, 23, 19–32.

Organizations can be led and managed in many different ways and there is no shortage of perspectives, models, and frameworks for thinking about how such tasks can be accomplished. This chapter focuses on one such perspective: evidence-based management (EBMgt). At its core is the idea that when managers and organizations make decisions, evidence of various types should be collected, critically appraised, and taken into account. Put this way, EBMgt does not appear to be either new or radical. However, as we shall go on to discuss, recent attempts to elaborate and flesh out this idea show that while some of its core principles are unremarkable, actually doing EBMgt presents major challenges, threats, and opportunities. Far from being business as usual, using evidence seriously and systematically appears to represent a significant departure from what organizations typically do.

This chapter starts with an account of the origins of the idea of evidence-based practice in other fields and how it has been adapted in the development of EBMgt. It then looks at the sometimes controversial notion of leadership and what we know about what managers and leaders do. We then consider the extent to which leaders, managers, and organizations are evidence-based in their approach to managing organizations and what can be done to further develop this approach. Finally, we discuss some of the challenges that managing in an evidence-based way present to leaders and to more traditional ways of thinking about what leadership entails.

Practitioners of all kinds, including managers, routinely use different forms of evidence in their work. So why do we need the idea of evidence-based practice if it’s already happening? The underlying problem or question evidence-based practice sets out to tackle is not whether practitioners use evidence at all but rather whether practitioners make the most effective use of all the forms of evidence that may be available to them.

Although there are important arguments and judgments to be made about what constitutes valid or relevant evidence in any particular setting, very few would question the principle of using evidence. At the same time, concerns are sometimes expressed about “analysis paralysis,” when action is delayed or not taken at all because of the time and effort required to gather and analyze evidence. However, in many areas of practice, including management and leadership, the opposite problem seems more apparent: that decisions and actions do not produce the desired outcomes because of insufficient regard for the evidence. While clear data are in short supply, something like evidence-based practice is already happening a bit, but it is not happening enough. Why does this problem occur?

There are many reasons why practitioners working in any domain might not make optimal use of evidence. For example, evidence may be difficult to interpret, hard or impossible to access, taken at face value and not critically evaluated, or contradictory. The perceived costs of collecting and using evidence may be judged to outweigh the perceived benefits. Clients and customers who use a practitioner’s services may not require or be too concerned about evidence for that practitioner’s work. At the same time, practitioners may be biased towards some forms of evidence. In particular, while personal experience is an extremely important source of evidence, it is also often overvalued or overemphasized at the cost of other evidence, which may present a different picture.

This form of bias is just one of many cognitive limitations which make it difficult for individuals to make the most effective use of evidence when making decisions or choosing a course of action. Other barriers can also be observed at group, professional, and organizational levels. Thus, even where evidence is available—and it often isn’t—using it effectively is far from easy.

Given the importance placed on health and the treatment of disease, it is perhaps not surprising that medicine was the first area of practice to adopt, develop, and explicitly use the evidence-based-practice idea—though it is surprising to those who assume that medical practice already was strongly evidence-based. A turning point in medicine was the publication of an editorial in the British Medical Journal claiming that “only about 15% of medical interventions are supported by solid scientific evidence” (Smith, 1991, p. 798). This had many effects but led ultimately to important changes in the way medical practitioners are trained and go about their work.

So what is evidence-based medicine? It has been defined by Sackett et al. (1997) as “integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research” in making decisions about patient care (p. 2). One of the most crucial features of evidence-based approaches to practice, and one often somehow forgotten, is that they involve the integration of professional experience with other sources of evidence. In other words, as we shall go on to discuss, evidence can come in many forms and from many sources, all are potentially important, and they need to be considered together in an integrative way.

One important difference between the general idea that practitioners should use evidence and the more specific idea of evidence-based practice is that the latter involves using evidence in a more systematic and explicit way. As further described by Sackett et al. (1997) evidence-based medicine is:

a process of life-long, self-directed learning in which caring for our own patients creates the need for clinically important information about diagnosis, prognosis, therapy and other clinical and health care issues in which we:

In other words, evidence-based approaches to practice do much more than simply suggest that individual practitioners should use more evidence. Rather, they attempt to specify processes and techniques than can be followed to use evidence in a more structured manner. In the case of medicine, this has involved, for example, changes in medical education, training, continuing professional development, and the ways in which evidence from medical research is reviewed, summarized, and made available to medical practitioners.

Since the creation of evidence-based medicine, researchers and practitioners working in many other areas, including education, social work, policy-making, architecture, and public health (Aarons, Hurlburt & Horwitz, 2011; Corrigan et al., 2001; De Groot, 2005; Field, 2002; Kitson et al., 1998; Lewis & Caldwell, 2005), have started to make overt links between this idea and their own disciplines. What all of these approaches have in common is the view that practice is not sufficiently informed by evidence in its many, varied forms.

The expression “evidence-based” is now well established in these and other disciplines and practices. Exactly what it means and how it can be achieved is much discussed and varies across fields. It was perhaps inevitable that these ideas would eventually also be applied to management.

As already suggested, the general idea of using evidence to make decisions is hardly new and already exists in a whole host of management ideas such as Quality, Just in Time and Management by Objectives. However, the specific idea of EBMgt is relatively new and draws on definitions and approaches to evidence-based practice developed in medicine and elsewhere.

The earliest discussions of how to apply evidence-based practice ideas to management are found in health-care management (e.g. Axelson, 1998). The early adoption of EBMgt in this sector presumably came about because managers in health organizations became aware of the evidence-based ideas that had already begun to be adopted by medical practitioners, and also perhaps because clinicians themselves were involved in management. However, it was several publications in 2006 that heralded the start of a wider discussion of EBMgt. Rousseau (2006), in her Academy of Management presidential address, asked the question, “Is there such a thing as evidence-based management?” and identified various ways in which management practice could be better informed by the research evidence produced by academics. In their book, Hard Facts, Dangerous Half-Truths and Total Nonsense: Profiting from Evidence-based Management, Pfeffer & Sutton (2006) set out some of the practical steps managers can take to become more evidence-based.

While these publications were aimed at different audiences and focused on different aspects of EBMgt, both made use of the basic principles underlying evidence-based medicine and demonstrated how they could be adapted to the practice of management.

Though some practitioners and academics have shown interest in the idea, it is important to note that EBMgt has not been enthusiastically received in all quarters. A number of academics have suggested that it has many limitations and may threaten management research (e.g. Learmonth & Harding, 2006; Morrell, 2008) while others have asked what evidence exists for EBMgt (Reay et al., 2009). To some extent, as discussed in Section 3.3.2, this is a reflection of the fact that EBMgt is a new and emerging idea and has not yet been sufficiently clearly defined.

It has been argued that many of the well-reasoned objections to EBMgt actually arise from a misunderstanding of EBMgt. Or rather, they are the consequence of unclear and underspecified definitions of EBMgt. In order to clarify what EBMgt is, and what it is not, Briner et al. (2009, p. 19) defined it as follows:

Evidence-based management is about making decisions through the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of four sources of information: practitioner expertise and judgment, evidence from the local context, a critical evaluation of the best available research evidence, and the perspectives of those people who might be affected by the decision.

“Conscientious” here means that practitioners and managers make planned, thoughtful, and sustained efforts to gather evidence from each of these four sources. This is important because otherwise the evidence which is easiest to get will be used whether or not it is reliable or relevant to the problem at hand. “Explicit” refers to being open and clear about what evidence has been found and communicating and recording it in a comprehensible way. This is to help ensure that all the evidence found is included, that those involved have a shared understanding of this evidence, and that any gaps can easily be identified. Of course, not all information or evidence is necessarily valid, relevant, or reliable and so it requires careful “critical evaluation” to determine, given the problem or question in hand, the quality and relevance of the evidence gathered.

A further challenge is to integrate these sources of knowledge and ensure that any decision that is made has taken account of evidence from each. Figure 3.1 gives a simple representation of how the decision takes place at the intersection of the four sources of evidence. The quantity, the quality, and the relevance of the evidence from each of these sources are unlikely to be equal. For example, the practitioner or management team facing a particular problem may have little evidence from experience on which to draw, some internal evidence, a lot of information about stakeholders’ preferences, and almost no external evidence. The nature and amount of evidence will also vary from problem to problem. EBMgt approaches emphasize the importance of trying to gather and consider evidence from all these sources when making decisions.

Figure 3.1 The elements of evidence-based practice (adapted from Briner et al., 2009).

Briner, R. B., Denyer, D., & Rousseau, D. M. (2009). Evidence-based management: Concept cleanup time? Academy of Management Perspectives, 23, 19–32.

But what types of evidence would be sought from each of these four areas? Table 3.1 shows a hypothetical example of the sorts of evidence a leader or management team might seek if they believed that their organization was insufficiently innovative and wanted to find ways of increasing levels of innovation. From the definition of EBMgt presented here, the presenting problem of low innovation and the proposed solution of intervening to increase innovation would be considered through a “conscientious, explicit, and judicious use” (Briner et al., 2009, p.19) of the four types of evidence suggested here. Evidence about practitioner expertise and judgments would be gathered by managers asking themselves questions about their own background in order to make their own experience and assumptions around innovation more explicit. The local context in this example is the organization, so the management team would identify existing data or collect new evidence around the perceived innovation problem and proposed solution. External evidence could include case studies or data from similar organizations who had similar problems and tried similar solutions. It would also come from published academic research on what is known and not known about how to assess innovation, what low innovation and its consequences might be, how levels of innovation can be increased, and what some of the positive and negative effects of these interventions might be. The perspectives and knowledge of stakeholders, in this case mostly employers and line managers, but also perhaps customers, are important for many reasons. For example, they may have insights into and other evidence concerning the perceived problem and proposed solutions not available from any other source.

The description and example of what doing EBMgt might entail presented in Section 3.3.2 is hypothetical. There is to our knowledge no research on how organizations do EBMgt, nor is there any research on the extent to which management and leadership takes an EBMgt approach. As mentioned earlier, all organizations use evidence. But that is not necessarily the same as doing EBMgt, even to a small degree. It seems likely that the extent to which something like EBMgt is practiced might depend on a number of organizational features, such as sector, size, the country in which it is based or in which it originated, culture, and so on.

In the absence of research on what EBMgt looks like in practice, it is still possible to suggest how an EBMgt-oriented organization might appear. Briner & Rousseau (2011) have done something similar, but for a specific group of professionals—industrial and organizational psychologists—rather than an organization. Based on the definition of EBMgt and what we already know about evidence-based practice in other fields, they drew up a checklist of features we might expect to see in any profession that practices in an evidence-based way. They suggested that in any evidence-based profession one would expect to find, for example, that its members access and make use of relevant academic research and that initial training and continuing professional development are based on evidence-based principles.

Table 3.1 Examples of the types of evidence gathered from each of the four sources to inform a decision about how to increase (a perceived low level of) innovation.

| Practitioner expertise and judgment | Evidence from the local context |

|

|

| The best available external research evidence | Perspectives of those who may be affected by the intervention |

|

|

Here, we suggest that a similar checklist can be drawn up to identify those characteristics we might expect to see in any organization that is trying to manage using an EBMgt approach. It can be argued that the EBMgt-oriented organization characteristics listed in Table 3.2 are not found frequently in organizations. For example, evaluation is relatively rare, errors are usually seen as reflecting weaknesses, decision-making is highly political and covert, and management fads are eagerly consumed. The behavior of leaders and senior managers may, as we go on to discuss in the next section, play a highly significant role in either facilitating or inhibiting EBMgt.

Table 3.2 Examples of characteristics found in EBMgt-oriented organizations.

| The organization takes steps to gather internal and external evidence in a systematic way and make sure it is accessible to managers and leaders (e.g. effective management information systems, data analysts, links to academic research). Organizational interventions and practices are evaluated. The reporting of failures and mistakes is encouraged. Errors are tolerated and used as learning opportunities. Decisions are made in a transparent way based on data and opinions (though the distinction is clear). Experimentation based on thorough initial analysis is encouraged. There is a healthy skepticism about management fads and fashions. Critical thinking is rewarded. Managers are rewarded for using an EBMgt approach. |

While there has been much written about leadership, the dimensions and definitions of the construct remain largely unclear (Riggio, 2008). The lack of clarity about what constitutes leadership, as in so many constructs within the realm of organizational behavior and psychology, is a consequence of the complexity and multiple layers which it entails. “Leadership” can encompass development, practice, attribution, or measurement of behavior. Attempts to reconcile leadership into a single coherent construct are of little benefit and the idea of leadership is probably best viewed as a composite of all of these elements. For the purpose of this chapter, we will be viewing leadership as practice; that is, the behaviors associated with leading people within organizational settings.

Before addressing the roles that evidence may play in leadership, it is worth pausing to consider the differences between leadership and management as discrete constructs. To date there have been several attempts to analyze how these concepts are related (e.g. Hales, 1986, 1999; Holmberg & Tyrstrup, 2010; Mintzberg, 1973; Tenglblad, 2006). In both common discourse and academic work, the terms “manager” and “leader” are often used interchangeably. The reason for this may be that there are many behavioral similarities between what leaders and managers actually do. Any differences that do exist are often minimal and are not always clearly observable in certain professions or at a given level within an organization.

While a detailed review of the meanings of leadership and management is beyond the scope of this chapter (though see for example Alvesson & Sveningsson, 2003; Bryman, 1992, 1993; Mintzberg, 1973; Pfeffer, 1977), what follows is an outline of how these constructs can be differentiated and how such differences are relevant to understanding the possible links between leadership and EBMgt.

As already noted, there has long been disagreement about the boundaries between leadership and management, and in turn the extent to which they overlap (Rost, 1991; Yukl, 1999). Management is generally associated with the pragmatism of ensuring that an organization functions, whereas, by contrast, leadership is more concerned with coping with and leading change, setting strategy, and the aspirational aspects of organizational development (Kotter, 1990). On another level, management is often characterized as an active process, while leadership is based on interaction (Mello, 2003) between leader and follower (Popper, 2011). The argument is sometimes made that while leaders can manage it is not always the case that managers can lead. However, even with this distinction, it can become difficult to identify the point at which one construct differs sufficiently from the other to be something separate. Such distinctions may have important implications for thinking about leadership and evidence-based practice and how to promote the use of evidence in organizations.

From a theoretical perspective, when we try to separate leadership from management there is one noticeable divide. Leadership has long been characterized by the promotion of charismatic (Conger & Kanungo, 1987, 1998; House, 1977), transformational (Bass, 1985; Burns, 1978), and visionary (Sashkin, 1988) approaches. All of these share the view that a leader instills moral purpose into an organization with the expectation of increased citizenship and the adoption of a shared vision. These theories encourage the leader to be disruptive of the status quo and to innovate not only in process, but in the direction in which they lead. This is in contrast to traditional managerial perspectives, which tend to champion organizational stability (Alvesson & Sveningsson, 2003) and the maintenance of structure over attempts to shape creativity, inspiration, and motivation (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1995).

It may be that managers rely on transactional models of leadership in the course of their everyday activities. These models are characterized by the exchange of valued rewards for the display of organizationally desired behaviors (Burns, 1978; Waldman et al., 1987). It seems reasonable to assume that decisions based within a transactional framework are more likely to be data- and outcome-driven. In contrast, transformational models of leadership encourage a reliance on an ability to articulate a vision, to inspire followers, and to intellectually stimulate subordinates (Lowe et al., 1996).

In separating management from leadership, the latter has been reserved for “the more dynamic, inspirational aspects of what people in authority may do” (Alvesson & Sveningsson, 2003, p. 1436). Leadership is different to management insomuch as it involves a commitment to the promotion of a specific vision and associated values. Leaders are expected to possess a degree of foresight not always present in those who manage on a daily basis. While both roles are important, a common view is that leaders do not concern themselves with the task-driven and more operational aspects of organizational life. As indicated earlier, while this may imply that leaders are able to manage, it does not always imply that all management is a discreet form of leadership.

For the purposes of this chapter, we do not use “manager” and “leader” as interchangeable labels and instead choose to focus on the role and function of the leader in organizational life as someone in a senior position of power, tasked not solely with the running of the organization but also with ensuring that it possesses and enacts a vision and a sense of purpose. In doing so, we hope to extend the reach of evidence-based practice into the realm of leadership in order to better construct the potential benefits that can be drawn from such an approach.

The fact is that we know relatively little about leader behavior in general and even less about how leaders make use of available evidence, let alone the extent to which this may differ from the way managers make use of it. However, we do know that these groups have different sources of evidence to draw on: something which may influence how evidence is subsequently used. While we cannot be sure about the extent to which the field of management is following that of medicine and beginning to adopt an evidence-based perspective, the sources of information leaders can use are only slowly growing.

It is believed by some that leaders possess a high degree of intuition and affective reasoning in how they lead (Barker, 2001). These beliefs have been perpetuated by trait-based theories of leadership, which view the ability or propensity to lead as something innate and therefore somewhat confined to a limited number of organizational members. The belief that leaders are themselves a special breed places a social pressure on them within the organization to maintain the perception (of both their superiors and subordinates alike) that their decision-making processes and behaviors are the result of intuition, “gut feeling,” or simply knowing what to do and when to do it. Indeed, it may be a desire to mystify the role of the leader that limits their willingness to consider an evidence-based approach in the course of their activities. Any leader who adopted a “conscientious, explicit, and judicious use” (Briner et al., 2009, p. 19) of evidence may lose some of their mystique, be seen as relying more on evidence than their personal experience, and allowing evidence rather than strong leadership to guide action.

Given how little we know about how leaders use evidence, the extent to which this chapter can be prescriptive is rather limited. Not surprisingly, the literature that examines the relationship between evidence and leadership (Lowe et al., 1996; Schaubroeck et al., 2007) tends to focus on the evidence for leadership practices rather than addressing the role of leaders in the adoption and promotion of evidence by organizations. However, there are three ways in which leaders can in principle encourage an adoption of evidence-based practice: (1) being an advocate for evidence; (2) being a collector and provider of evidence; and (3) providing the time and resources required for the effective use of evidence.

First, leaders can become advocates for evidence. One of the ways in which this can be achieved is by communicating in a more transparent manner about how they arrive at decisions. Any reluctance to engage in such behaviors might, as mentioned earlier, be driven by the perception that leadership should be driven largely by intuition. The use of evidence in leadership decisions could be seen as somehow trivializing the process away from leadership and towards data analysis. By advocating the use and benefits of evidence, the activities of leadership might also become more accessible to the masses (Tengblad, 2006). Yet this can also benefit followers and organizations alike, as subordinates begin to see the value placed on evidence, the manner in which evidence is used, and the possibility that they too can become evidence-based leaders in their own right. This might contribute to removing the mystique that often surrounds leadership and arguably could prepare organizations for more effective leader succession and distribution of leadership roles.

Advocacy can also be facilitated by the adoption of an interactionist style, which encourages a constant and informed interchange of professional information among colleagues without the restrictions of hierarchy and formal authority. This might take the form of an in-house repository of not only leadership decisions made and their rationales but also the evidence used to inform them. Since a central pillar of an evidence-based approach is the dissemination of evidence, it is of paramount importance that evidence not be retained or used for strategic advantage within the organization. Fostering a sense of collaboration around evidence is important, especially since it appears that the evidence-based leader facilitates work environments where there is a high tolerance for questioning processes and challenging the existing order of things (Harris, 1995).

Second, leaders can become both collectors and providers of evidence. Leaders who support the use of evidence should become aware of the evidence which they themselves generate. The successes and failures of any leadership approach, style, or intervention should be noted, since these are in themselves types of evidence. Having a willingness to engage in data collection and analysis for the purposes of self-development and improvement is to be encouraged. Another role of the evidence-based leader is their appreciation of knowledge management within an organization (Bukowitz & Williams, 1999). Their willingness to ensure that the organization generates wealth from its intellectual and knowledge-based assets may be key to nurturing evidence-based practice. This is demonstrated by the systematic, continuous, and purposeful approach to being aware of what organizational members do, what they need to know, and what they would need to know in order to improve in their respective roles.

Third, the evidence-based leader can promote the use of evidence by demonstrating a willingness to facilitate an organizational structure which provides individuals and work groups with the time and resources required (Harris et al., 2001) to analyze data, scrutinize evidence, and identify areas of action and development. Drawing on examples from education, Lewis & Caldwell (2005) note that “the challenge for leaders is to collect and report data and to be able to internalize it at the right time for the right reasons for the right students” (p. 182). While this may seem an obvious, if not excessively simple, practice, it is paramount to ensuring not only that evidence is gathered but that opportunities are provided to use it in a systematic manner, which includes its being subjected to critical appraisal for its validity and usefulness.

The roles which leaders can play in encouraging an evidence-based approach are simple in concept but more complex in execution. However, engaging in those behaviors that can “create and nurture an emphasis on strategic planning, action research, monitoring, evaluation and review” (Lewis & Caldwell, 2005, p. 184) is important. Those leaders who engage in such behaviors not only generate more positive evaluations of their overall leadership behaviors but also benefit from increased rates of adoption and implementation of evidence among organizational members (Aarons, 2006).

A common question among those introduced to the concept of EBMgt is the relative ease or difficulty of adopting a more evidence-based approach. The assumption is often made that such a transition requires a complex set of skills and learned behaviors and an extensive knowledge base. However, many of the ways in which leaders can become more evidence-based are relatively simple (Lewis & Caldwell, 2005). Having these practices articulated clearly and with examples from other organizations and occupational spheres is important in encouraging both adoption and implementation among those committed to evidence-based practice.

Several frameworks for the adoption of evidence-based practice currently exist, albeit outside of the specific disciplines of management and organizational psychology. Aarons et al. (2011) outline a detailed implementation process for the adoption of an evidence-based framework within public-service sectors. As one might expect, the foundation for this transition rests largely on the willingness of any particular organizational culture to embed evidence at the core of its practice. There is also a suggestion that the presence of a positive organizational culture (that is, one which encourages the open discussion and transparency of organizational processes) is associated with the sustained use of evidence in practice (Glisson & James, 2002). It appears that the organization whose leaders display a willingness to make psychological and tangible space for training on the use and benefits of evidence-based practice shows a greater degree of success in adoption and implementation (Aarons et al., 2011).

Another model for the adoption and implementation of evidence-based practice (Kitson et al., 1998) comes from the educational sector and suggests that the relationship between three core elements—the nature of the evidence being used, the context or environment in which the evidence will be used, and the method in which the process is facilitated—is paramount. This model again highlights the importance of creating an organization committed to development, progress, and improvement (Britton, 2002). At the centre of this relationship is the leader, who takes on the role of a facilitator and becomes responsible not only for championing the benefits of adopting evidence but also for helping to develop the technical competence required to complete the transition. Because of this, the leader must themselves first develop the competencies required to initiate the shift towards an evidence-based approach within the organization. If the leader is unclear on the rationale for adoption and the mechanisms needed to do so, they may have limited success in convincing other organizational members to follow them.

Much like the creation of a learning organization, a final model places emphasis on the leader in developing an organizational culture which is evidence-based. Pragmatically, this should take the form of providing training on what data to collect, how to collect them, and how they can be used to develop the organization. In addition to specific organizational cultures facilitating the adoption and promotion of an evidence-based perspective, it has been suggested that evidence-based practice can in turn affect the culture of the organization into which it is adopted (Potworowski & Green, 2012). Given that an organizational culture is heavily influenced by the values and actions of its leaders, they are in a position to facilitate the adoption of evidence-based practice, possibly more so than other organizational members.

Adopting an evidence-based approach to leadership is not without its challenges. As noted earlier, such an approach means that decisions take into account practitioner expertise, evidence from the local context, a critical evaluation of the best available research evidence, and the perspectives of those people who might be affected by the decision. The costs of adopting an evidence-based approach are borne principally by three groups: the leader, the organization that they lead, and the members or followers who make up that organization.

As already stated, in the case of the leader, the costs of evidence mean that they must accept a greater degree of transparency in how they lead and the sources which influence their decision-making. In this case, the cost might be the perception of the leader as being controlled by data rather than intuition or innate leadership abilities.

For the organization, the most notable cost of adopting an evidence-based approach is in the investment of time and other resources into switching from existing decision-making processes. Organizational members become wed to preexisting processes, and reversing that entrenchment can require a great degree of effort on the part of the organization. In addition to convincing members to adopt new, sometimes counterintuitive behaviors as part of their work role, there exists a need to ensure that the organization possesses the resources and skills required not only to seek out evidence but also to ensure that it becomes used in appropriate ways.

Finally, organizational members, while often being the main target of efforts to encourage an evidence-based approach, can often be overlooked as sources of evidence themselves. Since these people represent the organizational population that will be most affected by any behavioral shifts, they should be seen as valuable sources of information with respect to their organizational experiences and should be included in the compilation of evidence.

While there are costs present in becoming evidence-based, there are also benefits for followers and the organization alike. As indicated elsewhere, direct evidence for EBMgt is somewhat sparse, though there are many logical reasons for supposing that it is likely to have a number of benefits for organizations. While organizational change directed towards the adoption of an evidence-based approach can create resistance, research from medicine (Kitson et al., 1998) suggests that there are two principle barriers to the adoption and implementation of evidence-based practice that should be noted when assessing its costs: (1) individuals within organizations often lack the necessary analytic skills to adequately interpret and make use of available evidence; and (2) they lack the ability to implement and maintain initiatives once they have been launched. Both of these barriers highlight the fact that rather than simply following the best evidence, a full evidence-based approach requires a commitment to the entire process—the collection of evidence, critical appraisal of its value, its application to practice, and finally the evaluation of outcomes—in order to ensure that evidence-based practice itself generates further data to contribute to the existing body of evidence.

Finally, leaders can themselves be barriers towards the adoption of an evidence-based approach. It may be that leaders are uncomfortable with the degree of transparency required or with having others scrutinize their decisions. Also, leaders are often responsible for following agendas set by others (shareholders, CEOs, etc.) and it should therefore be recognized that “doing what works” may not always be how leadership performance is evaluated.

It is not enough to say that we need to know more about the role of EBMgt in leadership. We need to understand not only how people lead but also the extent to which they use evidence in the course of their decision-making processes. More importantly, we need also to shift our understanding and expectations of what constitutes evidence within the field and how it is, or is not, being used in the course of organizational leadership. It may be that the biggest barrier to the adoption of an evidence-based approach to leadership behaviors is a willingness to view leadership as a set of motivated behaviors accessible by all, rather than as something confined to a chosen few.

As stated earlier, leaders do not choose to ignore evidence; instead, evidence is usually difficult to obtain and understand, and where present, it can have a limited degree of perceived utility. The challenge ahead requires those who can distil research into evidence to invest the time and resources into doing so. In turn, those who use this evidence must actively engage with it and use their experiences to inform future evidence-based activity. Within leadership research, we must encourage the use of systematic reviews. Given the volume and scope of leadership research being produced within the field of organizational psychology, an important first step towards the adoption of evidence would be the production of evidence in a usable format. In order to achieve this, the discipline must begin the process of gathering, evaluating, and disseminating the findings of leadership research for consumption outside of the academic population. Of course, this is much easier said than done. The resources required to conduct well-structured, systematic reviews are difficult to acquire. A greater commitment must also come from those who would ultimately make use of such systematic reviews; namely, organizational leaders.

On a subject-specific note, the study of leadership would benefit greatly from the introduction and development of a framework for the collection and evaluation of different kinds of evidence. Given that theory and empirical work in the field of leadership produce different types of evidence, such a framework should incorporate that evidence that informs both the practice of leadership and its development. In addition to such a framework, practitioners and academics alike need to be given training on what data to collect, how they should be collected, and how they should be used in the course of leadership practice. The ultimate outcome of this would be to generate current and comprehensive systematic reviews in the area of leadership, but there are several steps which must first occur. As noted earlier, systematic reviews, while helpful, are time- and labor-intensive and can often pass the problem of interpretation down the line. In creating systematic reviews, the field must also ensure that these reviews are accessible and become familiar supplements to existing formal leadership instruction and training.

Following from this, leaders and organizations require a repository that can disseminate evidence to be used by practitioners and leaders alike. Other areas which have adopted an evidence-based approach (most notably medicine) have made use of such a repository, and with support it can rapidly become an iterative source in which a given population can find evidence to be incorporated into the practice of leadership. Finally, and most obviously, usable evidence on leadership lies at the intersection of academic and practitioner work. The need to have a degree of symbiosis between these parties is critical to the creation of a coherent evidence-based resource to draw upon.

As stated earlier, organizations can be led in many different ways, and what has been offered here is just one discreet perspective. EBMgt is not intended to override, subvert, or replace existing leadership styles or approaches. Instead, it offers an objective perspective from which leaders and followers can consider the role of evidence in the course of their decisions. The choice to use evidence is not in itself a solution. Adoption of evidence does not ensure good or even better leadership behaviors or organizational performance. What it does promote is a greater degree of transparency, openness to creating learning organizations, and, hopefully, processes which are defensible, open to refinement, and benefit the organization as a whole.

If anything is to be drawn from this chapter’s outline of EBMgt and leadership, it is that evidence, where available, should be incorporated into leadership behaviors and into the factors which influence decision-making in organizations. As highlighted in the practice of evidence-based medicine, evidence does not replace experience, but instead should be integrated into existing professional experience in order to create a more robust product.

The extent to which the adoption of evidence-based approaches is important to leadership is not yet clear. Simply put, we do not have sufficient evidence. However, whatever potential benefits exist are largely dependent on the leader who creates the conceptual space and tangible resources required for evidence to have a meaningful and valued place within the organization.

Aarons, G.A., Hurlburt, M., & Horwitz, S.M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38, 4–23.

Aarons, G.A. (2006). Transformational and transactional leadership: association with attitudes toward evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services, 57, 1162–1169.

Alvesson, M. & Sveningsson, S. (2003). Managers doing leadership: the extra-ordinarization of the mundane. Human Relations, 56, 1435–1459.

Axelson, R. (1998). Towards an evidence-based healthcare management. International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 13, 307–317.

Barker, R. (2001). The nature of leadership. Human Relations, 54, 469–94.

Bartlett, C.A. & Ghoshal, S. (1995) Changing the role of top management: beyond systems to people. Harvard Business Review, 73, 132–142.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and Performance beyond Expectations. New York: Free Press.

Briner, R.B., Denyer, D., & Rousseau, D.M. (2009). Evidence-based management: concept cleanup time? Academy of Management Perspectives, 23, 19–32.

Briner, R.B. & Rousseau, D.M. (2011). Evidence-based I-O psychology: not there yet. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 4, 3–22.

Britton, B. (2002). Learning for Change: Principles and Practices of Learning Organizations. Sundbyberg: Swedish Mission Council.

Bryman, A. (1992). Charisma and Leadership in Organizations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Bryman, A. (1993). Charismatic leadership in business organizations: some neglected issues. The Leadership Quarterly, 4, 289–304.

Bukowitz, W.R. & Williams, R.L. (1999). The Knowledge Management Fieldbook. Upper Saddle River, NJ; Financial Times/Prentice Hall.

Burns, J.M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper & Row.

Conger, J.A. & Kanungo, R.N. (1987). Toward a behavioral theory of charismatic leadership in organizational settings. Academy of Management Review, 12, 637–647.

Conger, J.A. & Kanungo, R.N. (1998). Charismatic Leadership in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Corrigan, P.W., Steiner, L., McCracken, S.G., Blaser, B. & Barr, M. (2001). Strategies for disseminating evidence-based practices to staff who treat people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 52, 1598–1606.

De Groot, H.A. (2005). Evidence-based leadership: nursing’s new mandate. Nurse Leader, 3, 37–41.

Field, K. (2002). Evidence-based subject leadership. Journal of In-service Education, 28, 459–474.

Glisson, C. & James, L.R. (2002). The cross-level effects of culture and climate in human service teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 767–794.

Hales, C.P. (1986). What do managers do? A critical review of the evidence. Journal of Management Studies, 23, 88–115.

Hales, C.P. (1999). Why do managers do what they do? Reconciling evidence and theory in accounts of managerial work. British Journal of Management, 10, 335–350.

Harris, A., Busher, H., & Wise, C. (2001). Effective training for subject leaders. Journal of In-service Education, 27, 83–94.

Harris, A. (1995). Effective Subject Departments. Bath, UK: University of Bath.

Holmberg, I. & Tyrstrup, M. (2010). Well then—What now? An everyday approach to managerial leadership. Leadership, 6, 353–372.

House, R. (1977). A theory of charismatic leadership. In J.G. Hunt & L.L. Larson, editors. Leadership: The Cutting Edge. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Kitson, A., Harvey, G., & McCormack, B. (1998). Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Quality in Health Care, 7, 149–158.

Kotter, J.P. (1990). A Force for Change: How Leadership Differs from Management. New York: Free Press.

Learmonth, M. & Harding, N. (2006). Evidence-based management: the very idea. Public Administration, 84, 245–266.

Lewis, J. & Caldwell, B.J. (2005). Evidence-based leadership. The Educational Forum, 69, 182–191.

Lowe, K.B., Kroeck, K.G., & Sivasubramaniam, N. (1996). Effectiveness correlates of transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analytic review of the MLQ literature. Leadership Quarterly, 7, 385–425.

Mello, J.A. (2003). Profiles in leadership: enhancing learning through model and theory building. Journal of Management Education, 27, 344–361.

Mintzberg, H. (1973). The Nature of Managerial Work. New York: Harper and Row.

Morrell, K. (2008). The narrative of “evidence based” management: a polemic. Journal of Management Studies, 45, 613–635.

Pfeffer, J. & Sutton, R.I. (2006). Hard facts, dangerous half-truths, and total nonsense: profiting from evidence-based management. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Pfeffer, J. (1977). The ambiguity of leadership. Academy of Management Review, 2, 104–112.

Popper, M. (2011). Toward a theory of followership. Review of General Psychology, 15, 29–36.

Potworowski, G. & Green, L.A. (2012). Culture and evidence-based management. In D.M. Rousseau, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Evidence-based Management. New York: Oxford University Press.

Reay, T., Berta, W., & Kohn, M.K. (2009). What’s the evidence on evidence-based management? Academy of Management Perspectives, 23, 5–18.

Riggio, R.E. (2008). Leadership development: the current state and future expectations. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 60, 383–392.

Rost, J. (1991). Leadership for the Twenty-first Century. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Rousseau, D.M. (2006). Is there such a thing as evidence-based management? Academy of Management Review, 31, 256–269.

Sackett, D.L., Richardson, W.S., Rosenberg, W., & Haynes, R.B. (1997). Evidence-based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. London: Churchill Livingstone.

Sashkin, M. (1988). The visionary leader. In J.A. Conger & R.N. Kanungo, editor. Charismatic Leadership: The Elusive Factor in Organizational Effectiveness. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schaubroeck, J., Lam, S.S.K., & Cha, S.E. (2007). Embracing transformational leadership: team values and the impact of leader behavior on team performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1020–1030.

Smith, R. (1991). Where is the wisdom…? The poverty of medical evidence. British Medical Journal, 303, 798–799.

Tengblad, S. (2006). Is there a “New Managerial Work”? A comparison with Henry Mintzberg’s classic study 30 years later. Journal of Management Studies, 43, 1437–1461.

Waldman, D.A., Bass, B.M., & Einstein, W.O. (1987). Leadership and outcomes of performance appraisal processes. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 60, 177–186.

Yukl, G. (1999). An evaluation of conceptual weaknesses in transformational and charismatic leadership theories. The Leadership Quarterly, 10, 285–305.