At the most basic level, to intervene is to enter into an ongoing system of relationships, to come between or among persons, groups, or objects for the purpose of helping them (Argyris, 1970). An organizational-development (OD) intervention refers to the range of planned, programmatic, and systematic activities intended to help an organization increase its effectiveness (Cummings & Worley, 2009). The process of organizational inquiry is characterized by methods that are based on varied degrees of action and collaboration advanced during the last (and the current) century, each of which seems to emphasize distinct scientific, collaborative, or action features (Adler et al., 2004; Coghlan, 2010). A set of interventions that aims at producing knowledge that is robust for scholars and actionable for practitioners may be found in the action modalities of action-research and collaborative-research knowledge streams (Coghlan, 2010; Shani et al., 2008).

In this chapter we take the perspective of OD as action research and collaborative management research and explore how a focus on a collaborative intervention is grounded in an insight into what is required and what any particular OD research intervention contributes (Coghlan, 2010). The chapter is structured as follows. First, we ground the issue of selecting an intervention in two foundational processes: action research and collaborative management research as exemplars of OD theory and practice and a general empirical method that is based on the operations of human knowing. Second, we explore several typologies of clustering OD interventions in terms of the two foundational processes. Our aim is to provide both a systematic overview of OD research interventions and a philosophical grounding of what these interventions do and how they might be selected within the theory and practice of OD in order that OD researchers may have a verifiable foundation for understanding and selecting appropriate research interventions.

The collaborative- and action-research orientations are based on a specific world view (ontology), an epistemology that expresses how we seek to know (the theory of knowledge), and methodologies that articulate the approach that is being adopted for inquiry (Coghlan, 2011).

Action research is one of the distinctive features of OD and its tap root was Lewin’s seminal work (Boje et al., 2012; Coghlan, 2012; Coghlan & Shani, 2010; Schein, 1989). Lewin was able to combine the methodology of experimentation with solid theory and a concern for action around important social concerns. Action research in OD is captured by the following definition:

… an emergent inquiry process in which applied behavioral science knowledge is integrated with existing organizational knowledge and applied to solve real organizational problems. It is simultaneously concerned with bringing about change in organizations, in developing self-help competencies in organizational members and in adding to scientific knowledge. Finally it is an evolving process that is undertaken in a spirit of collaboration and co-inquiry (Shani and Pasmore, 1985, p. 439).

From this definition it can be understood that action research is an emergent inquiry process that engages in an unfolding story, where data shift as a consequence of intervention and where it is not possible to predict or to control what takes place. It focuses on real organizational problems or issues, rather than issues created particularly for the purposes of research. It operates in the people-in-systems domain and applied behavioral science knowledge is both engaged in and drawn upon. Its distinctive characteristic is that it addresses the twin tasks of bringing about change in organizations and generating robust, actionable knowledge, in an evolving process that is undertaken in a spirit of collaboration and co-inquiry, whereby research is constructed with people, rather than on or for them.

In the view of Pasmore and his colleagues, collaborative management research may be defined as:

… an effort by two or more parties, at least one of whom is a member of an organization or system under study and at least one of whom is an external researcher, to work together in learning about how the behavior of managers, management methods, or organizational arrangements affect outcomes in the system or systems under study, using methods that are scientifically based and intended to reduce the likelihood of drawing false conclusions from the data collected, with the intent of both proving performance of the system and adding to the broader body of knowledge in the field of management (Pasmore et al., 2008, p. 20).

As such, collaborative management research is research that occurs in a natural setting within a specific business and industry context, involves true collaboration between practitioners and researchers, addresses an emerging specific issue of concern, uses multiple methodologies that are scientific, involves the creation of a learning system via the establishment of learning mechanisms, improves the system performance, and adds to the scientific body of knowledge in the field of management.

A comparative examination between these approaches reveals that both are focused on developing a deeper level of understanding of an important issue for both the system studied and the scientific community, in order to identify, modify, and transform the studied system. Both share the concern for the inquiry process and scientific rigor and both provide added value to management science.

In this section we discuss the construct of “dialogic” OD and how action research and collaborative management research may be exemplars of contemporary OD theory and practice.

Bushe & Marshak (2009) explore the emergence of new forms of OD in the postmodern world. They describe classical OD as “diagnostic OD,” where reality is an objective fact and diagnosis involves collecting and applying data and using objective problem-solving methods to achieve change, leading to an articulated desired future. As an alternative, they propose what they call “dialogic OD,” where organizations are viewed as meaning-making systems, containing multiple realities, which are socially constructed. Diagnostic OD is grounded in classical science and modernist philosophy and thought, and views organizations as living systems. In contrast, dialogic OD is influenced by the new sciences and postmodern thought and philosophy, and views organizations as meaning-making systems. Accordingly, dialogic OD views reality as socially constructed, with multiple realities that are socially negotiated rather than a single objective reality that is diagnosed. Data collection is less about applying objective problem-solving methods and more about raising collective awareness and generating new possibilities that lead to change. Accordingly, the focus of OD is on creating the space for changing the conversation. In sum, dialogic OD emphasizes changing the conversation in organizations by surfacing, legitimating, and learning from multiple perspectives and generating new images and narratives on which people can act.

Action research and collaborative management research, as presented here, may be understood as exemplars of contemporary dialogic OD. As we have described, both are foundational approaches in OD, whereby OD scholars and practitioners work together in learning about how the behavior of managers and employees, management methods, and organizational arrangements affect outcomes in the system under study. They use methods that are scientifically based and attempt to reduce the likelihood of drawing false conclusions from the collected data. The intent is to improve the performance of the system and add to the broader body of knowledge in the field of management (Coghlan, 2011, 2012; Mohrman et al., 2011; Shani et al., 2008). Both action research and collaborative management research meet the criteria of mode-2 knowledge production, which is inter- or transdisciplinary, is carried out in the context of concrete application, and is characterized by heterogeneity. In contrast to mode-1 research, which is characterized by explanatory knowledge generated in a disciplinary context, which in Gibbons et al.’s (1994) words is for many “identical with what is meant by science” (p. 3), mode 2 includes a wider, more temporary and heterogeneous set of practitioners collaborating on a problem defined in a specific and localized context, who are socially accountable and reflexive (MacLean et al., 2002).

Table 21.1 The general empirical method in OD.

| General empirical method | Questions |

| Be attentive to experience | What is the experience of the system? What is going on? What opportunities/problems are presenting? |

| Be intelligent in understanding | What insights into the experience do we have concerning: 1. the gap between actual and desired organizational state? 2. the congruence among relevant organizational characteristics? Whose insights are different (CEO, Exec Team, other members)? |

| Be reasonable in judging | Is it so? Does it fit the evidence? |

Human knowing comprises an invariant series of distinct operations: experiencing, understanding, and judging (Dewey, 1933; Lonergan, 1992; Meynell, 1998). In the context of OD, an organization and its members experience how the organization is functioning with respect to its engagement with its environment and its internal functioning. They seek insight into what that experience may mean and, through engagement with the OD researcher, explore multiple insights or understandings so as to form judgments as to which fit the evidence and thus take action to improve or transform the organization.

From the cognitional operations of experience, understanding, and judgment, a general empirical method that is simply the enactment of operations of human knowing may be derived (Coghlan, 2010). This method is grounded in:

Engaging this method requires the disposition to perform the operations of attentiveness, intelligence, and reasonableness, to which, when we seek to take action, is added responsibility (Table 21.1).

A word about method, particularly as the term tends to have connotations of being applied in a mechanistic and disembodied manner. We might distinguish between a method and a recipe; the latter delivers another instance of the same product. A method is not a set of rules to be followed meticulously. The key to method is the relationship between questioning and answering; it is a framework for collaborative creativity that deals with different kinds of question, each with its own focus. So questions for understanding specific data (What is happening here?) have a different focus from questions for reflection (Does this fit?) or from questions of responsibility (What ought I do?).

Porras & Robertson (1987) view the decision regarding which intervention to use as a stage process: first the selection of a feasible intervention set and then the selection of a particular intervention. The first stage, a broad set of potentially appropriate interventions, can be delineated by consideration of the general problem areas of organizational variables targeted for change. They classify the criteria into two general approaches: (1) the gap between actual and desired organizational states; and (2) the congruence among relevant organizational characteristics. In the second stage, change agents select the particular intervention(s) to be used. The criteria to be used in the second stage are clustered into three groups: readiness of the target system, leverage points, and the skills of the change agent.

To summarize this section, selecting an appropriate research intervention involves two processes. First, there is the collaborative process between OD researchers and organizational practitioners in the mode of “dialogic OD” (Bushe & Marshak, 2009) and action research and collaborative management research (Coghlan, 2011; Shani et al., 2008). Second, there is the method they use in assessing the experiences that lead to OD intervention and theory generation. The general empirical method provides an epistemological foundation for engaging with Porras & Robertson’s (1987) selection process. When OD researchers and practitioners attend to organizational experiences, converse together in an attempt to understand, and construct shared meanings (however provisional) from which appropriate OD research interventions may be selected and implemented, they are enacting in the general empirical method.

In the earlier days of OD, the suite of interventions available to OD researchers and practitioners was referred to as the “technologies of OD” (Burke, 1982; Burke & Hornstein, 1972). Contemporary scholarly OD books and textbooks no longer use this term. Rather they refer to “OD interventions” or “clustering OD interventions” (e.g. Coghlan & Shani, 2010; Cummings, 2008). Many different ways of clustering the wide range of interventions have been developed in the field over the past 60 years. As a consequence, many different ways of clustering intervention have been advanced in the OD literature.

There is little consensus as to how OD interventions may be clustered. Friedlander & Brown (1974) clustered OD interventions into sociotechnical approaches and human-process approaches, a framework that evolved to include human-resource and strategic approaches (Cummings, 2008; Cummings & Worley, 2009). A parallel framework emphasizes the focus on the primary target of the intervention: individuals, dyad/triads, teams and groups, intergroup relations, and the total organization (French & Bell, 1999). This framework may be incorporated into Cumming’s framework, as some individual interventions may be classified as human processes, others as human-resource interventions. Coghlan and Rashford (Coghlan & Rashford, 2006; Rashford & Coghlan, 1994) incorporated interlevel dynamics into levels of analysis as the focus for intervention. Ackerman (1986) identified three clusters of interventions based on the intervention process: developmental—the improvement of skills, methods, or conditions that for some reason are missing or needed; transitional—an OD program that is introduced to help the system construct a clear vision of what the organization aims to become; and transformational—radical change that requires a belief in and awareness of what is possible and necessary without a clear vision of what the final outcome will look like.

Fourteen “families” of OD interventions based on activities were advanced by French & Bell (1999): diagnostic activities, team-building activities, intergroup activities, survey-feedback activities, education and training activities, technostructural or structural activities, process-consultation activities, grid-organizational development activities, third-party peacemaking activities, coaching and counseling activities, life- and career-planning activities, planning and goal-setting activities, strategic planning activities, and organizational transformation activities. Blake & Mouton (1964) clustered OD interventions based on the underlying causal mechanisms: discrepancy intervention, theory intervention, procedural intervention, relationship intervention, experimentation intervention, dilemma intervention, perspective intervention, organization-structure intervention, and culture intervention. A set of four clusters of interventions that was based on action levers was advanced and labeled as: structural action levers, human-resources action leavers, technological action levers, and total-quality-management (TQM) action levers (Macy & Izumi, 1993). Mitki et al. (2000) identified three hybrid clusters based on the focus and the issue of the intervention (i.e. limited, focused, and holistic). Buono & Kerber (2008) differentiated between directed change, planned change, and guided changing interventions. Directed change is where there are tightly defined goals and leadership directs and commands. Planned change is where there is a clear goal and vision of the future and leadership devises a roadmap to reach it and influences how it is reached. Guided changing is where the direction is loosely defined and leadership points the way and keeps watch over the process. Beer & Nohria (2000) identified two clusters based on the intended outcomes: interventions that focus on economic results (the “E”) and those that focus on developing capabilities (the “O”).

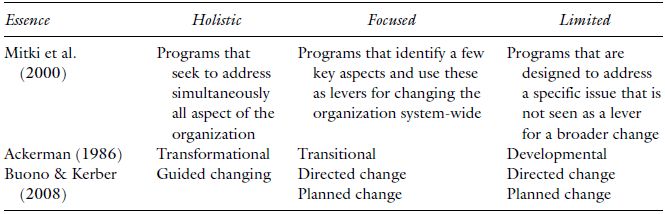

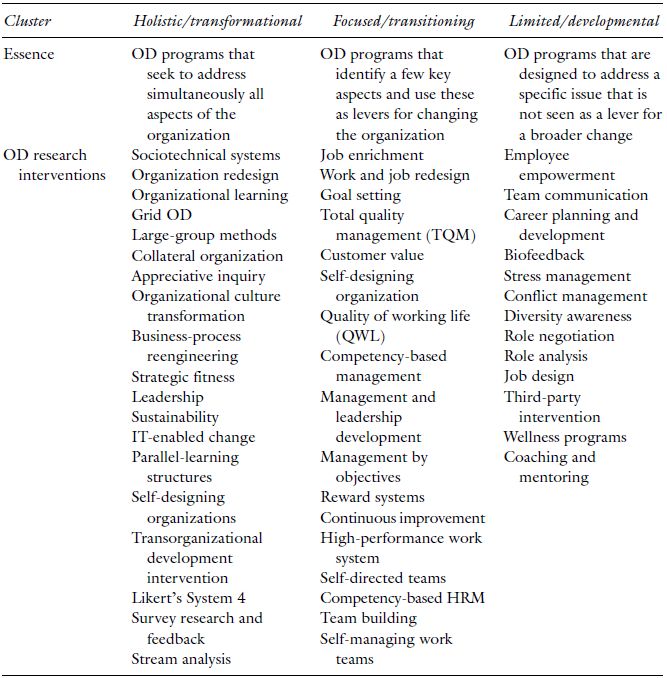

Table 21.2 Alternative clustering of OD interventions.

We are adopting Mitki et al.’s (2000) classification as our foundational framework, into which we integrate Ackerman’s (1986) and Buono & Kerber’s (2008) frameworks (Table 21.2). Underpinning this approach is the assumption that selecting an OD technology is context- and issue-based, and is the fruit of the action-research and collaborative-management-research processes.

As Table 21.2 demonstrates, a holistic-change program is one that seeks to address simultaneously all aspect of the organization and so accords with both Ackerman’s (1986) notion of “transformational” and Buono & Kerber’s (2008) “guided changing” approach. Focused-change programs are those which identify a few key aspects of the organization, use these as levers for changing the organization system-wide, accord with being transitional, and follow a directed- or planned-change approach. Limited programs are designed to address a specific issue that is not seen as a lever for a broader change. They accord with being developmental and follow a directed- or planned-change approach.

Holistic programs are intentionally aimed at simultaneously addressing all (or most) aspects of the organization and entirely transforming it. These OD programs follow a system-wide perspective and tend to incorporate many elements within and outside the organization boundaries in the process. Due to the complexity of the system-wide interventions, internal and external practitioners tend to partner with one another in facilitating the process.

Examples of OD interventions in this category include: Grid OD, or change by design as it was later called (Blake & Mouton, 1969; Blake et al., 1989), System 4 (Likert, 1967), strategic fitness profiling (Beer, 2011; Fredberg et al., 2011), sociotechnical systems (STSs) (Felton & Taylor, 1994; Eijnhaten et al., 2008; Pasmore, 1988), large-group methods, such as search conference, future search, world cafe, and democratic dialogue (Bunker & Alban, 2005; Emery & Purser, 1996; Gustavsen, 1992; Holman et al., 2007; Lifvergren et al., 2011; Polanyi, 2001; Weber & Manning, 1998), collateral organization (Zand, 1974), parallel-learning structures (Bushe & Shani, 1990, 1991), appreciative inquiry (Bushe & Kassam, 2005; Reed, 2007), organizational-culture transformation (Cameron, 2008; Heracleous, 2007; Schein, 2010), organizational learning (Argyris, 1995; Lundberg, 1989; Mohrman & Mohrman, 1997; Sackmann et al., 2009; Shani & Docherty, 2004), sustainability development (Armenakis et al., 1999; Shani et al., 2010; Worley & Parker, 2011; Zandee, 2011), stream-analysis intervention (Porras, 1987), IT-enabled change (Barrett et al., 2006; Hussain & Hafeez, 2007; McDonagh & Coghlan, 2006), mergers and acquisitions (Auster & Sirower, 2002; Chreim, 2007; Kovoor-Misra, & Smith, 2007; Marmenout, 2010; Meyer, 2006; Seo, 2005; Zhou & Canella, 2008), transformation (Bartunek & Louis, 1988), transorganizational development intervention or interorganizational collaboration and networks (Coughlan & Coghlan, 2011; Cummings, 1984; Mohrman et al., 2003; Vangen & Huxham, 2003), and design-science approach (Bate, 2007).

There are many holistic interventions, a number of which would not be traditionally classified as OD—business-process reengineering being a clear example. As OD has developed, it has learned to work with non-OD interventions, and so in this section we include references that bring an OD perspective to these interventions. For example, Taylor (1998) presents an integrative OD change program that pulls together STSs, business-process reengineering, and SAP into one coherent system-wide intervention. Stebbins et al. (1998) describe a business-process reengineering blueprint that integrated a hybrid of change initiatives.

Focused programs are ones that identify a few key aspects, such as time, quality, and customer value, and then use them, by design, as levers for changing the organization system-wide. The OD focused programs tend to integrate specific content-knowledge expertise (such as quality or quality-improvement experts) in the intervention process, seem to be facilitated by a combined team of internal and external practitioners, and require a combined technical and system-wide knowledge. The nature of the focused OD programs is such that in order for the intervention to serve as a trigger for a system-wide change at a later stage, it is critical to invest in building trusting relationships and legitimacy, and demonstrate the intervention’s added value as the change effort develops. This is because the effectiveness of the inquiry and intervention is likely to be based on a collaborative relationship between researchers and managers, in which the status and expertise of the manager and the research expertise of the researcher need to be complementary and in harmony. This does not happen without effort.

Examples of OD interventions in this category are: job restructuring (Tichy & Nisberg, 1976), management by objectives (French & Hollmann, 1975), self-designing organizations (Cummings & Mohrman, 1987), reward systems (Lawler, 1987), continuous improvement (Lillkrank et al., 1998), high-performance work systems and self-directed teams (Macy et al., 2007), competency-based human-resource management (Boyatzis, 1996), executive leadership development (Bass & Avioli, 1990; Torbert, 1989), TQM (Coyle-Shapiro, 1999, 2002), and quality working life (QWL) (Cummings & Mohrman, 1987; Levin & Gottlieb, 1993; Pasmore, 1988).

OD interventions in this category play a critical role in many organizations which for a variety of factors are not ready to face a system-wide change effort. As such, they are often crucial in the development of readiness for a system-wide change effort (holistic program). The key aspect(s) that the intervention focuses on carries a major symbolic value as it triggers the process of reframing the issues, challenges, and organizational learning. The OD activities, phases, and mechanisms that are established during the focused-program process often serve to guide and/or launch the holistic program.

Limited OD programs are not aimed at affecting broader aspects of the organization. By design they address a specific problem that is not seen as a lever for broader change, but may help build a foundation for broader change at a later date. The basic logic for limited OD programs is the need to address and solve a specific issue, such as individual career progression, conflict resolution, job boredom, employee wellness, or a communication problem. The intervention has a clear purpose and time frame, delineated activities, phases, a beginning, and an end.

Examples of OD interventions in this category include: career development (Hall & Morgan, 1977), stress management (Ivancevich et al., 1990), confrontation meeting (Beckhard, 1967), role negotiation, (Harrison, 1972), conflict management (Walton, 1987), employee fitness and wellness (Gebhardt & Crump, 1990), work–life balance (Caproni, 2004; Reiter, 2007), employees and jobs (Hornung, & Rousseau, 2007; Grunberg et al., 2008; Jimmieson et al., 2008; Miller & Robinson, 2004; Shperling & Shiron, 2005), team building (Bushe & Coetzer, 2007; Edmondson, 2004; Wageman et al., 2005), and mentoring and coaching (Chandler & Kram, 2007; Kram, 1985).

In approaching OD research interventions, we apply the general empirical method (Table 21.3). While it may appear somewhat simple, it is not so. Attending to experience, articulating the meaning of that experience, and coming to judgment in an organization is a complex process, as different experiences exist and there are different perspectives on what these experiences might mean and what might be done. OD researchers engage the parties in the conversation in an attempt to construct and articulate the organization’s current state and desired future state. These conversations are initiated by the person who invites the OD researchers into the organization and progress through the organization as the CEO and researchers co-design and co-implement the research.

For illustration purposes, an STS intervention as a holistic OD program includes specific activities and phases that by design address all three areas of the general empirical method. The intervention provides an opportunity for organizational members to focus on their everyday work experience and share the experience with others in a purposefully created study group, with the intent of creating shared meaning or understanding current work-related dynamics, processes, and outcomes. This new understanding leads to the identification of central issues that need to be addressed and the exploration of alternative possible OD interventions that might help address the emerging issue. Thus, a judgment call is made about the specific intervention to pursue. Study teams will be created to focus on the understanding of the social, technical, and environmental subsystems of the organization. Scientific methods will be used to collect and interpret data. Based on the shared interpretation of the data, new understanding is achieved and specific ideas for change are generated. The ideas are shared with top management and, based on the identification of relevant criteria, decisions are made on specific change implementations. As such, STS follows the general empirical method described above.

Table 21.3 An overview of OD interventions.

Collaborative efforts to understand collective experiences and to create action on the basis of that understanding may find expression within some of the action modalities that make up the broad field of action research and collaborative management research (Coghlan, 2010). For example, if an organization has a practice of using action learning as a key mechanism for problem solving and management development, this practice may be leveraged for OD research. This is because action learning is built around: (1) addressing problems (by which is meant an issue that has no single solution and has advocates who understand the problem differently); (2) a diverse group of peers who explore the problem together in (3) a reflective manner based on experience, with a commitment to both (4) action and (5) learning, with (6) the help of a learning coach (Marquardt et al., 2009). Accordingly, an organization with such a practice is already attuned to the practices of collaborative inquiry and action learning and may readily be realigned to a collaborative-research approach, with the OD researcher acting as the learning coach (Coughlan & Coghlan, 2011). Similarly, a clinical inquiry/research approach facilitates shared inquiry into organizational dysfunctions, so as to generate insight into how they occur and action strategies to deal with them (Coghlan, 2009; Schein, 2008). These examples are illustrative of how specific orientations within the broad field of collaborative research may be engaged in the selection and implementation of OD research interventions.

The clustering of the OD research interventions presented above is anchored in the general empirical method of human knowing and collaborative research. The perspective taken in this chapter, as we have seen, differs from the traditional and previously articulated typologies of OD intervention clustering. Instead of clustering the OD interventions based on human versus technostructure approaches (Friedlander & Brown, 1974) or a developmental-process focus (Ackerman, 1986), target focus (French & Bell, 1999), change-orientation focus (Buono & Kerber, 2008), or outcome focus (Beer & Nohria, 2000), we adopted the hybrid of issue, change orientation, and target perspective proposed by Mitki et al. (2000). Coupling the hybrid-based clustering with the action-research and collaborative-research orientation presents unique opportunities and a set of challenges that can benefit from future research.

Considerable research in the field of OD has identified many barriers as major problems in OD work. For example, Beer & Eisenstat (2000) identified “six silent killers”: unclear strategy and values and conflicting priorities; an ineffective senior-management team; a top-down or laissez-faire leader; poor coordination and communication across functions, businesses, or geographic entities; inadequate leadership development and leadership resources below the top; and poor vertical communication. The challenge from an OD perspective is how to begin an open dialogue that will lead to an appropriate choice of OD intervention. The “dialogical OD” view of reality is socially constructed, where there are multiple views of reality in an organization. This suggests the need to collaborate systematically on the creation of a common meaning on the basis of which joint action may be taken. Action research and the collaborative-management-research orientation provide the mechanisms for such a process.

Organizational development through action research and collaborative management research is viewed as an effort by two or more parties, at least one of which is a member of the organization or system under study and at least one of which is an external researcher, who work together in learning about an issue of shared importance, using methods that are scientifically based and intended to reduce the likelihood of drawing false conclusions from the data collected (Pasmore et al., 2008). Thus, adopting the action-research and collaborative-management-research orientation is likely to enhance the process of creating a shared meaning for the issue at hand. Furthermore, the more accurate the data collected, the more individuals are involved in the creation of a shared meaning for the data, and the more the collective is involved in the exploration of possible OD interventions, the greater the likelihood that the chosen OD intervention will be the most appropriate for the system.

The OD literature, as we have seen, encompasses a wide variety of OD interventions, clustered in different ways, each based on its own rationale. The clustering logic advanced in this chapter is based on a hybrid of identified issue, general change orientation, and target or level, in order to address both an organization’s capability development and its economic performance. The underlying premises of OD work advanced in this chapter and the striving for the enhancement of human knowing suggest that the proposed clustering of OD interventions should be treated as a broad platform for dialogue and not as a rigid template for action.

The emerging dialogical orientation in OD work provides an opportunity to develop a shared understanding of the need for change, an opportunity to identify and choose the most appropriate way to frame the change, an opportunity to choose the most appropriate OD intervention, and an opportunity to design for a sustainable change (Pasmore, 2011). From a research perspective, the opportunities to generate robust scientific knowledge are promising, as many layers of intriguing questions can be investigated. For example, we need to investigate the appropriateness and relevance of the different ways of clustering OD interventions. We need to know more about the possible causal relationship between the dialogical process, the generation of shared meaning, and the success of a chosen intervention. We also need to know more about the specific role that situational factors play in impacting the dialogical process and in determining OD-intervention success.

Facilitating the dialogical process and collaborative research in OD work suggests that the OD researchers or scholarly practitioners are embedded in the art and science of action-research and collaborative-management-research philosophies, approaches, and methodologies. At the center of action research, collaborative management research and the dialogical process is a set of activities that triggers the development of a community of inquiry as a way of engaging in developing new understanding (Coghlan & Shani, 2008). Such a community does not stand alone; rather, it is part of a web of internal and external networks, as the OD researcher is a member of several OD research networks and the managers are members of their own networks. The quality of the community of inquiry is likely to impact the effectiveness of the production of new knowledge that is both relevant to practice and of added scientific value.

The need to produce collaborative research that is rigorous, reflective, and relevant is critical (Woodman et al., 2008). Coupling the notions of community of inquiry, collaborative research, dialogical OD, and OD interventions provides an opportunity to explore a wide variety of research questions. For example, if rigor is viewed as upholding the standards of scientific proof in assessing the impact of a specific organizational issue on performance, we need to learn more about how can we develop this insight while using a dialogical process that is embedded in scientifically generated data, data analysis, and data interpretation. If reflection is viewed as the process of jointly and collectively creating new insights and theories by referring to the related work of others, we need to learn more about the situational factors that might impact the quality of reflection and about the design choices of the dialogical process that might facilitate the creation of the most appropriate context for that reflection. Finally, if we view relevance as addressing an important organizational issue, we need to learn more about how to create a psychological safety net such that organizational members from different levels in the organizational hierarchy can have an honest dialogue about issues, about the role that the OD practitioner can play in facilitating such dialogue, and about the learning mechanisms that can be designed to enhance the quality of the dialogue.

In this chapter we have taken the perspective of OD as action research and collaborative management research and explored how a focus on a collaborative intervention is grounded in an insight into what is required and what any particular OD technology contributes. In our view, selecting an intervention is grounded in two foundational processes: action research and collaborative management research, as exemplars of OD theory and practice and a general empirical method that is based on the operations of human knowing. It is from this foundation that engagment with intervention clusters is based. While we selected one particular clustering that, for us, provides the richest exploitation of the literature, it is our view that the essential element of cluster selection emerges from the collaborative engagement between OD researchers and practitioners. Our aim has been to provide both a systematic overview of OD research interventions and a philosophical grounding for what these interventions do and how they might be selected within the theory and practice of OD in order for OD researchers to have a verifiable foundation for understanding and selecting an appropriate research intervention.

Ackerman, L. (1986). Development, transition, or transformation: the question of change in organizations. OD Practitioner, December, 1–8.

Adler, N., Shani, A.B. (Rami), & Styhre A. (2004). Collaborative Research in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Argyris, C. (1970). Intervention Theory and Method. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Argyris, C. (1995). Action science and organizational learning. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 10(6), 20–26.

Armenakis, A.A., Harris, S.G., & Feild, H.S. (1999). Making change permanent: a model for institutionalizing change interventions. In R.W. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 12. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 97–128.

Auster, E.R. & Sirower, M.L. (2002). The dynamics of mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 38(2), 216–244.

Barrett, M., Grant, D., & Wailes, N. (2006). ICT and organizational change. Special Issue Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 42(1).

Bartunek, J.M. & Louis, M.R. (1988). The interplay of organization development and organizational transformation. In R.W. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 2. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 97–134.

Bass, B.M. & Avolio, B.J. (1990). The implications of transactional and transformational leadership for individual, team, and organizational development. In R.W. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 4. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 231–272.

Bate, P. (2007). Bringing the design sciences to organization development and change and change management. Special Issue, Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 43(1).

Beckhard, R. (1967). The confrontation meeting. Harvard Business Review, 45(2), 149–155.

Beer, M. (2011). Developing an effective organization: intervention, method, empirical evidence and theory. In A.B. (Rami) Shani, R.W. Woodman, & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 19. Bingley, UK: Emerald. pp. 1–54.

Beer, M. & Eisenstat, R. (2000). The silent killers of strategy implementation and learning. Sloan Management Review, Summer, 82–89.

Beer M. & Nohria, N. (2000). Cracking the code of change. Harvard Business Review, 78(3), 133–141.

Blake R.R. & Mouton, J.S. (1964). The Managerial Grid. Houston: Gulf.

Blake, R.R. & Mouton, J.S. (1969). Building a Dynamic Corporation through Grid Organization Development. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Blake, R.R., Mouton, J.S., & McCanse, A. (1989). Change by Design. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Boje, D., Burnes, B., & Hassard, J. (2012). The Routledge Companion to Change. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Boyatzis, R.E. (1996). Consequences and rejuvenation of competency-based human resource and organization development. In R.W. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 9. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 101–122.

Bunker, B.B. & Alban, B. (2005). Large group interventions. Special Issue, Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 41(1).

Buono, A.F. & Kerber, K.W. (2008). The challenge of organizational change: enhancing organizational change capacity. Revue Sciences de Gestion, 65, 99–118.

Burke, W.W. (1982). Organization Development: Principles and Practices. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

Burke, W.W. & Hornstein, H. (1972). The Social Technology of Organization Development. Fairfax, VA: NTL Resources.

Bushe, G.R. & Kassam, A.F. (2005). When is Appreciative Inquiry Transformational? A Meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 41(2), 161–181.

Bushe, G.R. & Coetzer, G.H. (2007). Group development and team effectiveness: using cognitive representations to measure group development and predict tasks performance and group viability. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 43(2), 184–212.

Bushe, G.R. & Marshak, R. (2009). Revisioning organization development: diagnostic and dialogic premises and patterns of practice. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 45(3), 248–268.

Bushe, G. & Shani, A.B. (Rami) (1990). Parallel learning structure interventions in bureaucratic organizations. In R.W Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 4. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 167–194.

Cameron, K. (2008). A process for changing organization culture. In T.G. Cummings, editor. Handbook of Organization Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. pp. 429–446.

Caproni, P.J. (2004). Work/life balance: you can’t get there from here. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 40(2), 208–218.

Chandler, D.E. & Kram, K.E. (2007). Reconceptualizing mentoring at work: a developmental network perspective. In H.P. Gunz & M.A. Peiperl, editors. Handbook of Career Studies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chreim, S. (2007). Social and temporary influence on interpretations of organizational identity and acquisition integration. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 43(4), 449–480.

Coghlan, D. (2009). Toward a philosophy of clinical inquiry/research. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 45(1), 106–121.

Coghlan, D. (2010). Seeking common ground in the diversity and diffusion of action research and collaborative management research action modalities: toward a general empirical method. In W.A. Pasmore, A.B. (Rami) Shani, & R. Woodman, editors. Research in Organization Change and Development, vol. 18. Brinkley, UK: Emerald. pp. 149–181.

Coghlan, D. (2011). Action research: exploring perspectives on a philosophy of practical knowing. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 53–87.

Coghlan, D. (2012). Organization development and action research: then and now. In D. Boje, B. Burnes, & J. Hassard, editors. The Routledge Companion to Change. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 357–367.

Coghlan, D. & Rashford, N.S. (2006). Organization Change and Strategy: An Interlevel Dynamics Approach. New York: Routledge.

Coghlan, D. & Shani, A.B. (Rami). (2008). Collaborative Management Research through Communities of Inquiry. In A.B. (Rami) Shani, S.A. Mohrman, W.A. Pasmore, B. Stymne, & N. Adler. Handbook of Collaborative Management Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. pp. 601–614.

Coghlan, D. & Shani, A.B. (Rami), editors. (2010). Fundamentals of Organization Development, four volumes. London: Sage.

Coughlan, P. & Coghlan, D. (2011). Collaborative Strategic Improvement through Network Action Learning. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Coyle-Shapiro, J.A.-M. (1999). TQM and organizational change: a longitudinal study of the impact of a TQM intervention on work attitudes. In R.W. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 12. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 129–170.

Coyle-Shapiro, J.A.-M. (2002). Changing employee attitudes: the independent effects of TQM and profit sharing on continuous improvement orientation. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 38(1), 57–77.

Cummings, T.G. (1984). Transorganization development. In B. Staw & L. Cummings, editors. Research in Organization Behavior, vol. 5. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 367–422.

Cummings, T.G. (2008). Handbook of Organization Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cummings, T.G. & Mohrman, S.A. (1987). Self designing organizations: towards implementing quality-of-work-life innovations. In R.W. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 1. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 275–310.

Cummings, T.G. & Worley, C.G. (2009). Organization Development and Change, 9th edition. Cincinnati, OH: South-Western.

Dewey, J. (1933). How We Think. Lexington, MA: Heath.

Edmondson, A. (2004). Learning from mistakes is easier said than done: group and organizational influences on the detection and correction of human error. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 40(1), 66–90.

Emery, M. & Purser, R. (1996). The Search Conference. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Fredberg, T., Norrgren, F., & Shani, A.B. (Rami). (2011). Developing and sustaining change capability via learning mechanisms: a longitudinal perspective on transformation. In A.B. (Rami) Shani, R.W. Woodman, & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 19. Bingley, UK: Emerald. pp. 117–161.

French, W.L. & Hollmann, R.W. (1975). Management by objectives: the team approach. California Management Review, 17(3), 13–22.

Friedlander, F. & Brown, L.D. (1974). Organization development. Annual Review of Psychology, 25, 313–341.

Gebhardt, D.L. & Crump, C.E. (1990). Employee fitness and wellness programs in the workplace. American Psychologist, 45(2), 262–272.

Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., & Trow, M. (1994). The New Production of Knowledge. London: Sage.

Grunberg, L., Moore, S., Greenberg, E.S., & Sikora, P. (2008). The changing workplace and its effects: a longitudinal examination of employee responses at a large company. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 44(2), 215–236.

Gustavsen, B. (1992). Dialogue and Development. Assen, NL: Van Gorcum.

Hall, D.T. & Morgan, M.A. (1977). Career development and planning. In W. Clay Hamner & F.L. Schmidt, editors. Contemporary Problems in Personnel, review edition. Chicago: St Clair Press. pp. 205–226.

Harrison, R. (1972). Role negotiation. In W.W. Burke & H. Hornstein, editors. The Social Technology of Organization Development. Fairfax, VA: NTL. pp. 84–96.

Heracleous, L. (2007). An ethnographic study of culture in the context of organizational change. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 37(4), 426–446.

Holman, P., Devane, T., & Cady, S. (2007). The Change Handbook, 2nd edition. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Hornung, S. & Rousseau, D.M. (2007). Active on the job—proactive in change: how autonomy at work contributes to employee support for organizational change. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 43(4), 401–426.

Hussain, Z. & Hafeez, K. (2007). Changing attitudes and behavior of stakeholders during an information-led organization change. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 44(4), 490–513.

Ivancevich, J., Matteson, M., Freedman, S., & Phillips, J. (1990). Worksite stress management interventions. American Psychologist, 45(2), 252–259.

Jimmieson, N.L., Peach, M., & White, K.M. (2008). Utilizing the theory of planned behavior to inform change management: an investigation of employee intentions to support organizational change. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 44(2), 237–262.

Kram, K.E. (1985). Mentoring at Work: Developmental Relationships in Organizational Life. Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman.

Kovoor-Misra, S. & Smith, M. (2007). In the aftermath of an acquisition: triggers and effects on perceived organizational identity. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 44(4), 422–444.

Lawler, E.E. (1987). The design of effective reward systems. In J.W. Lorsch, editor. Handbook of Organizational Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. pp. 255–271.

Levin, I.M. & Gottlieb, J.Z. (1993). Quality management: practice risks and value-added roles for organization development practitioners. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 29(3), 296–310.

Lifvergren, S., Docherty, P., & Shani, A.B. (Rami). (2011). Towards a sustainable healthcare system: transformation through participation. In S.A. Mohrman & A.B. (Rami) Shani, editors. Organizing for Sustainability, vol .1. Brinkley, UK: Emerald. pp. 99–125.

Likert, R. (1967). The Human Organization. New York: McGraw-Hill

Lillrank, P., Shani, A.B., Kolodny, H., Stymne, B., Figuera, J.R., & Liu, M. (1998). Learning from the success of continuous improvement change programs: an international comparative study. In R.W. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 11. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 47–72.

Lonergan, B.J. (1992). Insight: an essay in human understanding. F. Crowe & R. Doran, editors. The Collected Works of Bernard Lonergan, vol. 3. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Original publication 1957.

Lundberg, C.C. (1989). On organizational learning: implications and opportunities for expanding organizational development. In R.W. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 3. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 61–82.

MacLean, D., MacIntosh, R., & Grant S. (2002). Model 2 Management Research. British Journal of Management, 13(2), 189–207.

Macy, B.A. & Izumi, H. (1993). Organizational change, design, and work innovation: a meta-analysis of 131 North American field studies—1961–1991. In R.W. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 7. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 235–313.

Macy, B.A., Farias, G.F., Rosa, J.F., & Moore, C. (2007). Built to change: high-performance work systems and self-directed work teams—a longitudinal quasi-experimental field study. In R.W. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 16. Oxford: Elsevier. pp. 337–416.

Marmenout, K. (2010). Employee sense making mergers: how deal characteristics shape employee attitudes. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 46(3), 329–359.

Marquardt, M., Leonard, S., Freedman, A.M., & Hill, C. (2009). Action Learning for Developing Leaders and Organizations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

McDonagh, J. & Coghlan, D. (2006). Information technology and the lure of integrated change: a neglected role for organization development? Public Administration Quarterly, 30, 22–55.

Meyer, C.B. (2006). Destructive dynamics of middle management intervention in postmerger processes. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 42(4), 397–419.

Meynell, H. (1998). Redirecting Philosophy: Reflections on the Nature of Knowledge from Plato to Lonergan. Toronto: Toronto University Press.

Miller, M.V. & Robinson, C. (2004). Managing the disappointment of job termination: outplacement as a cooling device. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 40(1), 49–65.

Mitki, Y., Shani, A.B. (Rami), & Stjernberg, T. (2000). A typology of change programs. In R.T. Golembiewski, editor. Handbook of Organizational Consultation, 2nd edition. New York: Marcel Dekker. pp. 777–785.

Morhman, S.A., Lawler, E.E., & Associates. (2011). Useful Research: Advancing Theory and Practice. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Mohrman, S.A. & Mohrman, A.M. Jr. (1997). Fundamental organizational change as organizational learning: creating time-based organizations. In R.W. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 10. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 197–228.

Mohrman, S.A., Tenkasi, R., & Mohrman, A.M. (2003). Social networks and planned organizational change: the impact of strong network ties on effective change implementation and use. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 39(3), 301–323.

Pasmore, W.A. (1988). Designing Effective Organizations: The Sociotechnical System Perspective. New York: Wiley.

Pasmore, W.A. (2011). Tipping the balance: overcoming persistent problems in organizational change. In A.B. (Rami) Shani, R. Woodman, & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organization Change and Development, vol. 19. Brinkley, UK: Emerald. pp. 259–292.

Pasmore, W.A., Stymne, B., Shani, A.B. (Rami), Mohrman, S.A., & Adler, N. (2008). The promise of collaborative management research. In A.B. (Rami) Shani, S.A. Mohrman, W.A. Pasmore, B. Stymne, & N. Adler. Handbook of Collaborative Management Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. pp. 7–31.

Polanyi, M. (2001). Toward common ground and action on repetitive strain injuries: an assessment of a future search conference. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 37(4), 465–487.

Porras, J.I. (1987). Stream Analysis. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Porras, J.I. & Robertson, P.J. (1987). Organization development theory: a typology and evaluation. In R. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organization Change and Development, vol. 1. Greenwich, CT: JAI. pp. 1–58.

Rashford, N.S. & Coghlan, D. (1994). The Dynamics of Organizational Levels. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Reed, J. (2007). Appreciative Inquiry: Research for Change. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Reiter, N. (2007). Work Life Balance: What do YOU Mean? Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 43(2), 273–294.

Sackmann, S.A., Eggenhofer-Rehart, P.M., & Friesl, M. (2009). Sustainable change: long term efforts towards developing a learning organization. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 45(4), 521–549.

Schein, E.H. (1989). Organization development: science, technology or philosophy? MIT Sloan School of Management Working Paper, 3065-89-BPS. Reproduced in D Coghlan &A.B. (Rami) Shani, editors. (2010). Fundamentals of Organization Development, vol. 1. pp. 91–100. London: Sage.

Schein, E.H. (2008). Clinical inquiry/research. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury, editors. Handbook of Action Research, 2nd edition. London: Sage. pp. 226–279.

Schein, E.H. (2010). Organizational Culture and Leadership, 4th edition. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Seo, M.-G. (2005). Understanding the human side of mergers and acquisitions: an integrative framework. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 41(4), 422–443.

Shani, A.B. (Rami), Mohrman, S.A., Pasmore, W., Stymne, B., & Adler, N. (2008). Handbook of Collaborative Management Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Shani, A.B. (Rami) & Pasmore W.A. (1985). Organization inquiry: towards a new model of the action research process. In D.D. Warrick, editor. Contemporary Organization Development: Current Thinking and Applications. Scott Foresman and Company: Glenview, IL. pp. 438–448. Reproduced in D. Coghlan & A.B. (Rami) Shani, editors. (2010). Fundamentals of Organization Development, vol. 1. London: Sage. pp. 249–260.

Shani, A.B. & Stjernberg, T. (1995). The integration of change in organizations: alternative learning and transformation mechanisms. In R.W. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 8. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 77–122.

Shani, A.B. (Rami), Woodman, R., & Pasmore, W.A., editors. (2011). Research in Organization Change and Development, vol. 19. Brinkley, UK: Emerald.

Shperling, Z. & Shiron, A. (2005). A field experiment assessing the impact of the focused diagnosis intervention on job autonomy. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 41(2), 222–240.

Stebbins, M.W., Shani, A.B. (Rami), Moon, W., & Bowles, D. (1998). Business process reengineering at Blue Shield of California: the integration of multiple change initiatives. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 11(3), 216–232.

Steel, R.P. & Jennings, K.R. (1992). Quality improvement technologies for the 90s: new directions for research and theory. In W.A. Pasmore & R.W. Woodman, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 6. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 1–36.

Taylor, J. (1998). Participative design: linking BPR and SAP with STS approach. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 11(3), 233–245.

Tichy, N.M. & Nisberg, J.N. (1976). When does job restructuring work? Organizational Dynamics, 5(1), 63–80.

Torbert, W.R. (1989). Leading organizational transformation. In R.W. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 3. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 83–116.

van Eijnatten, F., Shani, A.B. (Rami), & Leary, M. (2008). Sociotechnical systems: designing and managing sustainable organizations. In T. Cummings, editor. Handbook of Organization Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. pp. 277–309.

Vangen, S. & Huxham, C. (2003). Nurturing collaborative relations: building trust in interorganizational collaboration. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 39(1), 5031.

Vansina, L.S. & Tallieu, T. (1996). Business process reengineering or sociotechnical system design in new cloth? In R.W. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 9. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 81–100.

Wageman, R., Hackman, J.R., & Kehman, E. (2005). Team diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 41(1), 373–398.

Walton, R.E. (1987). Managing Conflict: Interpersonal Dialogue and Third Party Roles, 2nd edition. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Weber, P.S. & Manning, M.R. (1998). A comparative framework for large group organizational change interventions. In R.W. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore, editors. Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol. 11. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 225–252.

Worley, C.G. & Parker, S.B. (2011). Building multi-stakeholder sustainability networks: the Cuyahoga Valley initiative. In S.A. Mohrman & A.B. (Rami) Shani, editors. Organizing for Sustainability, vol. 1. Bingley, UK: Emerald. pp. 187–214.

Zand, D.E. (1974). Collateral organization: a new change strategy? Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 10(1), 63–69.

Zhou, J., Shin, S.I., & Canella, A.A. (2008). Employee self-perceived creativity after mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 44(4), 397–421.