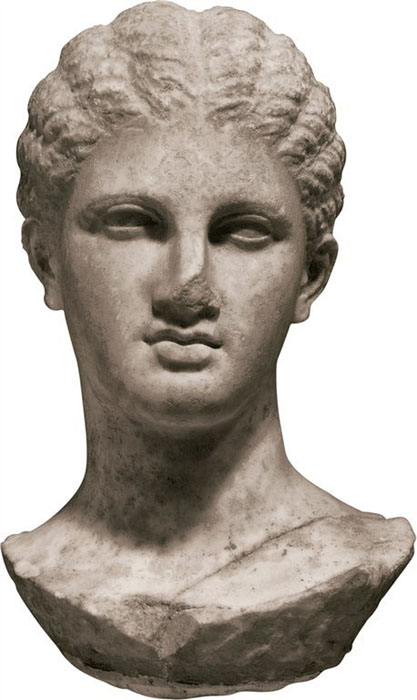

Head of a Young Woman from a Grave Naiskos,

c. 320 BCE. Classical. Fine-grained white marble,

34.3 x 15.6 x 22.2 cm. The Getty Villa, Malibu.

Ancient Greeks and Romans

The early Greek authors described creation as a stupendous hollow globe cut in the centre by the plane of the earth. The upper hemisphere lit by magnificent luminaries; the lower hemisphere filled with perpetual darkness. The top of the higher sphere is heaven, the bright dwelling of the Olympian gods; its bottom is the surface of the earth, the home of living men. The top of the lower sphere is Hades, the abode of the ghosts of the dead; its bottom is Tartarus, the prison of the Titans, rebellious giants vanquished by Zeus. Earth lays half-way from the surface of heaven to the floor of Tartarus. This distance is so great that, according to Hesiod, it would take an anvil nine days to fall from the centre to the nadir or the lowest point. Some of the ancients seem to have surmised the spherical nature of the earth, and to have thought that Hades was simply its dark side, the dead being our antipodes. In the Odyssey, Ulysses reaches Hades by sailing across the ocean stream and passing the eternal night land of the Cimmerians, whereupon he comes to the edge of Acheron, the moat of Pluto’s sombre house. Virgil also says, “One pole of the earth to us always points aloft; but the other is seen by black Styx and the infernal ghosts, where either dead night forever reigns or else Aurora returns thither from us and brings them back the day.”(Virgil, Georgics) But the prevalent notion evidently was that Hades was an immense hollow region not far under the surface of the ground, and that it was to be reached by descent through some cavern, like that of Avernus. This subterranean place is the destination of all human beings, rapacious Orcus, the Roman god of the underworld, spared no-one, good or bad. It is wrapped in obscurity, as the etymology of its name implies an invisible place. “No sun e’er gilds the gloomy horrors there; No cheerful gales refresh the stagnant air.” (Virgil, Georgics II. 242-250)

The dead are hopeless in Hades and the living learn to fear this dismal realm. The shade of the valiant hero dwelling there, the swift-footed Achilles stated, “I would wish, being on earth, to serve for hire another man of poor estate, rather than rule over all the dead.” Souls retain their physical characteristics, the fresh and ghastly appearance of the wounds that have encumbered them. Groups of fellow countrymen, circles of friends, congregate together, preserving their remembrance of earthly fortunes and beloved relatives left behind, and eagerly questioning each newly arriving soul for tidings from above. When the soul of Achilles is told of the glorious deeds of Neoptolemus, “he goes away taking mighty steps through the meadow of asphodel in joyfulness, because he had heard that his son was very illustrious.” The dying Antigone says, “Departing, I strongly cherish the hope that I shall be fondly welcomed by my father, and by my mother, and by my brother.” It is important to notice that, according to the early and popular view, this Hades, the “dark dwelling of the joyless images of deceased mortals,” is the destination of universal humanity. In opposition to its dolorous gloom and repulsive inanity are vividly pictured the glad light of day, the glory and happiness of life. The incomparable son of Peleus said:

Not worth so much to me as my life, are all the treasures which populous Troy possessed, nor all which the stony threshold of Phoebus Apollo contains in rocky Pytho. Oxen, and fat sheep, and trophies, and horses with golden manes, may be acquired by effort; but the breath of man to return again is not to be obtained by plunder nor by purchase, when once it has passed the barrier of his teeth.

It is not probable that all the ornamental details illustrated by the poets with the fate and state of the dead as they are set forth, for instance, by Virgil in the sixth book of the Aneid were ever credited as literal truth. But there is no reason to doubt that the essential features of this mythological scenery were accepted in the vulgar belief. For instance, that the popular mind honestly held that, in some vague sense or other, the ghost, on leaving the body, flitted down to the dull banks of Acheron and offered a shadowy obolus to Charon, the rugged old ferryman, for a passage in his boat, seems attested not only by a thousand averments to that effect in the current literature of the time, but also by the invariable custom of placing an obolus in the dead man’s mouth for that purpose when he was buried.

The Greeks did not view the banishment of souls in Hades as a punishment for sin, or the result of any broken law in the plan of things. It was to them merely the fulfilment of the inevitable fate of creatures who must die, in the order of nature, like successive growths of flowers, and whose souls were too feeble to rank with gods and climb into Olympus. That man should cease from his substantial life on the bright earth and subside into sunless Hades, a vapid form, with nerveless limbs and faint voice, a ghostly vision bemoaning his existence with idle lamentation, or consuming himself with the hazy mockeries of his former pursuits, was melancholy enough; but it was rather his natural destiny, and not an avenging judgment.

However, that powerful instinct in man which desires to see villainy punished and goodness rewarded perpetuates, among so cultivated a people as the Greeks, to develop a doctrine of future compensation for the contrasted deserts of souls. The earliest trace of the idea of retribution which we find carried forward into the invisible world is the punishment of the Titans, those monsters who tried climbing mountains, storming the heavenly abodes, and seizing Thunderer’s bolts from his hand. In addition, mythological characters such as Sisyphus, Tantalus, and Tityus are all punished by Zeus for their impiety and therefore condemned to a severe expiation in Tartarus. Finally, we discern a general prevalence of the belief that punishment is distributed, not by vindictive caprice, but on the grounds of universal morality. All souls wait in Hades to be judged according to their merits by Rhadamanthus, Minos, or Aeacus. The distribution of poetic justice in Hades at last became, with many authors so melodramatic as to furnish a fair subject for burlesque. A good example of this is outlined in the Emperor Julian’s Symposium. The gods prepare for the Roman emperors a banquet, in the air, below the moon. The good emperors are admitted to the table with honours; but the bad ones are hurled headlong down into Tartarus, amidst the derisive shouts of the spectators.

As the notion that the wrath of the gods would pursue their enemies in the future state gave rise to a belief in the punishments of Tartarus, so the notion that the distinguishing kindness of the gods would follow their favourites gave rise to the myth of Elysium. The Elysian Fields were earliest portrayed lying on the western margin of the earth, stretching from the verge of Oceanus, where the sun set at eve. They were covered with perpetual greenery, perfumed with the fragrance of flowers, and eternally refreshed by cool breezes. They were represented merely as the select abode of a small number of living humans, who were either the mortal relatives or the special favourites to the gods, and who were transported there to pass an immortality which was described, with great inconsistency, sometimes as purely happy, sometimes as joyless and wearisome. To all except a few chosen ones this region was utterly inaccessible. Homer says, “But for you, O Menelaus, it is not decreed by the gods to die; but the immortals will send you to the Elysian plain, because you are the son-in-law of Zeus.” If the inheritance of this clime had been proclaimed as the reward of heroic merit, and if it had been believed achievable by virtue, it would have been held up as a prize to be attained. The whole account, as it was at first, bears the imprint of imaginative fiction as legibly upon its front as the story of the dragon-watched garden of Hesperus’s daughters, whose trees bore golden apples, or the story of the enchanted isle in the Arabian tales.

The early location of Elysium and the conditions of admission to it were gradually changed; and at length it reappeared, in the underworld, as the abode of the just. On one side of the primitive Hades, Tartarus was designed to admit the condemned into its penal tortures, and on the other side Elysium was lowered down to reward the justified by receiving them into its peaceful and perennial happiness; while, between the two, Erebus remained as an intermediate state of negation and gloom for those in limbo. The vivid descriptions of this subterranean heaven, frequently found there, were rarely accepted as solid verities. They were scarcely ever used, to our knowledge, as motives in life, incitement in difficulties, and consolation in sorrow. They were mostly set forth in poems and other fictitious works. They were often denied and ridiculed in speeches and writings received with public applause. Still, they unquestionably exerted some influence on the common modes of thought and feeling, contributed to the shadowy in the popular imagination and heart, helped men to conceive of a blessed life hereafter and to long for it, and took away something of the artificial horror with which, under the power of rooted superstition, their departing ghosts hailed the shadowy limits of futurity.

From the examination of Greek mythology it can be inferred that the dead, a dull populace of ghosts, pass through the neutral melancholy of Hades without discrimination. And finally we discern in the world of the dead a sad middle region, with a Paradise on the right and a hell on the left, the whole presided over by three incorruptible judges, who appoint the newcomers their places in accordance to their moral worth.

The question now arises: What did the Greeks think in relation to the ascent of human souls into heaven among the gods? Did they except none from the remediless doom of Hades? Was there no path for the wisest and best souls to climb starry Olympus? To dispose of this inquiry fairly, four distinct considerations must be examined. First, Ulysses sees in the infernal regions the image of Hercules shooting the shadows of the Stymphalian birds, while his soul is said to be rejoicing with fair legged Hebe at the banquets of the immortal gods in the skies. To explain this, we must remember that Herakles was the son of Alcmene, a mortal woman, and of Zeus, the king of the gods. Accordingly, in the flames on Mount Oeta, the surviving ghost which he derived from his mother descends to Hades, but the purified soul inherited from his father has the proper nature and rank of a deity, and is received into the Olympian synod. Of course no blessed life in heaven for the generality of men is here implied. Hercules, being a son and favourite of Zeus, has a corresponding destiny exceptional from that of other men.

Secondly, another double representation, somewhat similar, but having an entirely different interpretation, occurs in the case of Orion, the handsome Hyrian hunter whom Artemis loved. At one time he is described, like the spectre of the North American Indian, chasing over the Stygian plain the disembodied animals he had in his lifetime killed on the mountains:

Swift through the gloom a giant hunter flies: A ponderous brazen mace, with direful sway, Aloft he whirls to crush the savage prey; Grim beasts in trains, that by his truncheon fell, Now, phantom forms, shoot o’er the lawn of hell.