8

The Gold of the Gods

In the summer of 1993 I traveled to Las Vegas to interview von Däniken about the truths and lies of The Gold of the Gods, his third best seller. The Imperial Palace Hotel was the setting of a new convention, but not of the usual kind. The members of the International Ancient Astronauts Society, founded by von Däniken with an American, Gene Phillips, filled the poker and roulette tables.

Someone introduced me to Peter Krassa, the secretary of the association, and he sent me to the floor where I could find von Däniken. I was really excited to meet the author of Chariots of the Gods? Memories of the Future—Unsolved Mysteries of the Past, a book and movie that greatly influenced my way of thinking and exploring. Later on I would discover the real father of the ancient astronaut theory was George Hunt Williamson, who was also related to the South American archaeological past.

The door opened, and a rosy-cheeked man who looked too tan and hot greeted me affably. It didn’t take us long to start talking about the Tayos. “It’s true,” he said, “I never entered the cave. I lied. I did it because the way Moricz told the story wasn’t the style people liked back then. Let’s just say I embellished the story. I gave it a new layer of poetic white lies, narrated in the first person.”

This testimony shook me. The rumor was true. But even if my image of von Däniken was shattering before me, I still respected the spirit of the man who revealed the “astronaut gods” and who had influenced my early incursions in the mysteries of the universe. But why did it happen this way?

There is a clear before and after in the story of the Tayos, an inflection point that happened about forty-five years ago, with the meeting between Moricz and von Däniken. At that point the discovery of that subterranean world was not really known—we could even claim it was a local discovery—but with the arrival of the Swiss author, the Tayos Cave became an international sensation.

The Gold of the Gods made von Däniken a star. This brought a wave of tourism to the area, especially explorers from North America, where the book sold millions of copies. Today it is easy to find editions from that decade in used bookstores.

Recently, von Däniken tried (poorly) to clear his ethical faults in a redundant and dismal book whose German title means “fake evidence,” although in English and Spanish it was called History Lies. The title and the content of the book reflect the unclear statements of the author regarding the enigma of the Tayos. But let’s see how this endless saga began.

Von Däniken arrived in Ecuador like a tiger blinded by his own greed, giving in to opportunism and speculations, inspired by what the news said about the discovery of the century. This is how von Däniken met Moricz and his lawyer, Peña Matheus, and they would take him to places that everyone knew were not the Tayos Caves. Moricz’s modus operandi was becoming clear, and the people he saw realized he would not comply with the rules and codes of control regarding the Tayos Caves.

The scientific and archaeological community continued the controversy, which also kept the book in the best-seller lists in the midseventies. Von Däniken touched a sore spot, because anthropologists do not find it easy to accept that a cave in South America has remains of the oldest civilizations known to man.

Von Däniken tells us how his adventure began: “I met Juan Moricz on March 3, 1972. For two days his lawyer, Peña Matheus from Guayaquil, tried to reach him through telegrams and phone calls. I got comfortable in his office and had enough reading material to last me for days. I must confess I was a little nervous, because all the stories said Moricz was a hard man to reach. Finally a telegram reached him, and he called us on the phone. He had heard about my books! ‘I will speak to you,’ he said.

“The night of March 3 a man in his mid-forties [Moricz] stood before me with tan skin, heavy build, and gray hair. He was silent. This is the kind of man you need to talk to. My questions, which were impulsive and urgent, amused him. Little by little he started talking objectively and very concretely about his caves.

“‘But that doesn’t exist!’ I said.

“‘Sure they do,’ interrupted Peña, ‘I have seen them with my own eyes. Moricz took me to visit the caves.’”

But Moricz, in his famous interview with the German newsmagazine Stern would say he never took the writer to the Tayos Caves, nor did he show him the metallic library. Moricz’s lawyer would vouch for him, as he did in the last years of visits and personal interviews (see his statement in appendix C of this book).

In an article I wrote, “When Moricz discovered the tunnel system, he was poor, and would continue to be so until the end of his days. So far he had discovered some sites with iron and silver, and he granted the exploitation permit to metallurgical workshops. This helped him attain a better economic situation that, with a frugal lifestyle, allowed him to dedicate his time exclusively to his explorations. Juan Moricz estimated that only an inspection of the tunnel system, without going into details, would cost about one million Swiss francs back then, for the installation of an electrical station, construction of storage spaces for devices, instruments and supplies, security measures, and even some subterranean work.”

It is clear that Moricz was disappointed with the failed expeditions and the truncated contacts with institutions, which were often his own fault because he couldn’t make up his mind about the topic. Von Däniken’s statements confirm that the Hungarian did not lose hope about finding funding to help him clear up a discovery that had been keeping him up at night since 1965. But the real challenge was discovering if Moricz was telling the truth when he said he had never shown the entrance to von Däniken, and if the latter lied to his audience.

In The Gold of the Gods von Däniken wrote:

For all those who write to me and ask me to plan an expedition to the caves, and to give more details about the subterranean installations, I must specify: I was not a member of Moricz’s Expedition of 1969, and I never went to the main entrance of any of the subterranean installations. Moricz only took me to a secondary entrance, and I spent a total of about 6 hours inside the tunnels.

As with all my previous books, The Gold of the Gods is not a scientific book. It is true the facts written there could be real, and they are. But I did decide to add a little suspense and humor to the bluntness of the facts, and I don’t think the author should be punished for being creative; this is what writing is all about. Journalists may like it or not, but they do the same!

If we intended to criticize every case, there wouldn’t be enough Stern magazines for it. Thanks to my editorial contacts I know the attacks against von Däniken are good for the business. And just to show you I am not as close-minded as my critics, I will tell you I don’t mind, and I understand it a little. Even if sometimes it hurts me.

Moricz spoke the truth when he told journalists that I had not participated in the expedition of ’69. What these partial falsehoods fail to mention is that I never said such a thing. But they shouldn’t have said either that I never visited these places in the photos, because I did visit a lateral entrance in 1972 with Moricz. The photos we took that time were never published because Moricz refused to do so; he even threatened us, because he was afraid if we published them, thousands of frenzied treasure hunters would start showing up. I promised not to publish them, haven’t done it so far, and don’t intend to do it, no matter what you say. I am a man of my word. . . . In 1972 we came to an agreement on what could be published in The Gold of the Gods about this system of caves. It was clear I wouldn’t disclose the geographic location of the entrances.

Years later, Moricz would confess to Stanley Hall: “von Däniken was not important to me at all. The truth is I feel sorry for him. He destroyed the greatest story of all time, something that surely broke him from the inside after his initial lie.”

Von Däniken and his publisher were asking for $1 million from the earnings of the book, which had sold about ten million copies around the world, to be paid for a few pages, a small part of the book that Moricz invented, because he wanted to verify the content, the truth, something he didn’t move a finger for. They had already offered him funding for an expedition.

“I answered Moricz’s demands,” said von Däniken, “and he confirmed to the newspapers the existence of the subterranean world and a metallic library. In the De Bunte magazine from Ecuador, in autumn 1976 (after Hall’s expedition), there was a debate and all the participants were disappointed in me, because no treasure had been found in the Tayos Caves.”

When The Gold of the Gods was published in 1974, the scandal began again. The book reviewers deformed the story, as did the filmmaker Ut Uterman, who would never finish his documentary on the Tayos in the seventies. Wilhelm Robertoff and Edwin Park were also involved in trying to tell the story. Von Däniken’s book and all the publicity around the world created the perception that Ecuador is a place of suspense.

Plate 1. Map created by Alex Chionetti to show the expedition routes of 1968, 1969, and 1976

Plate 2. Map created by Alex Chionetti to show the locations of his expeditions.

Plate 3. Tayos hut in the fog of the Morona-Santiago province

Plate 4. Light streams into the opening of the Chumbitayo Cave

Plate 5. The author examining polished blocks inside the Chumbitayo Cave

Plate 6. Gold on the ceiling of the cave

Plate 7. Fog near the Llanganates mountain range

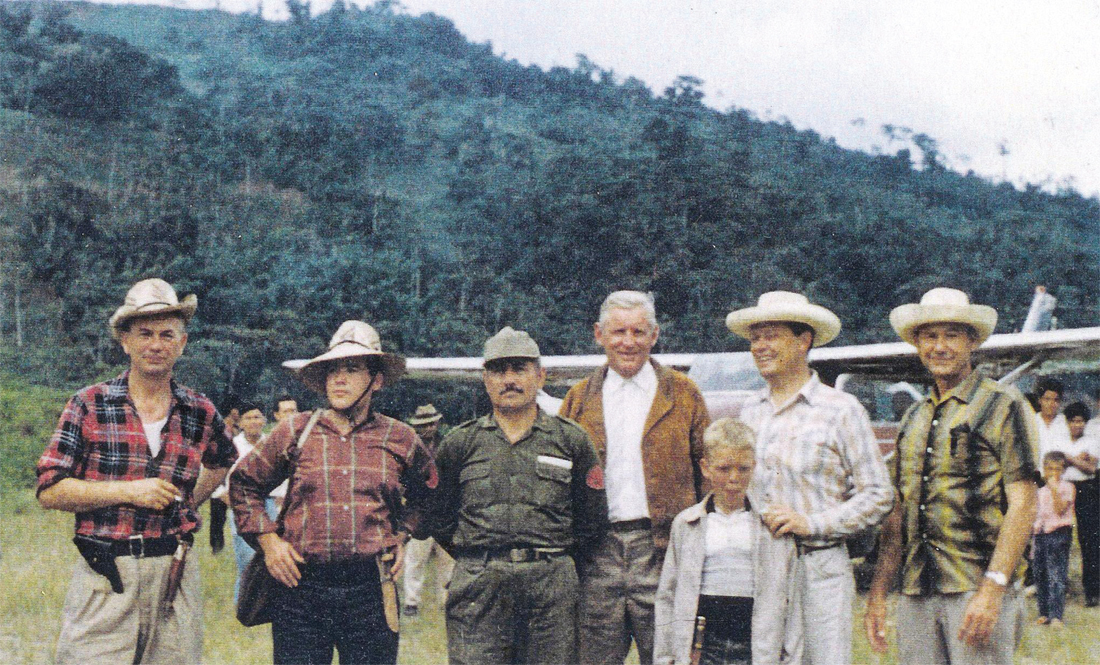

Plate 8. Juan Moricz and Julio Goyén Aguado during the Mormon expedition with Avril Jesperson on the far right

Plate 9. Neil Armstrong gets ready to descend farther into the caves

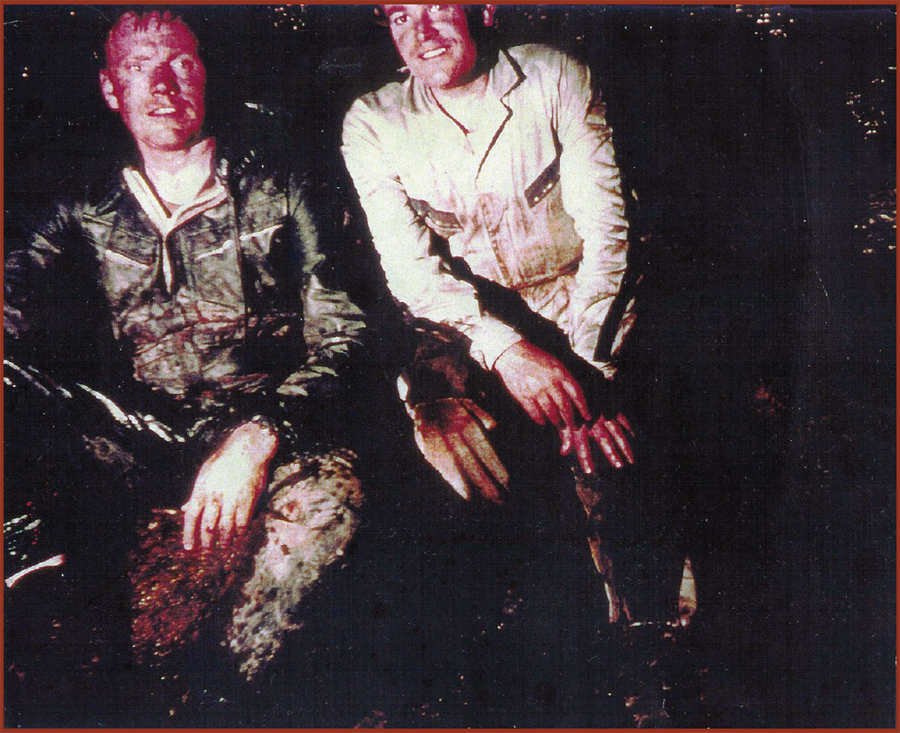

Plate 10. Neil Armstrong (left) with Julio Goyén Aguado (right) during the 1976 expedition

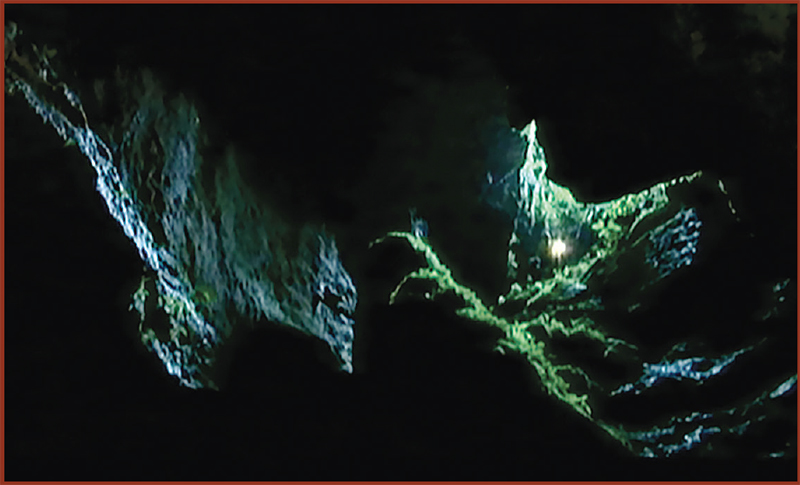

Plate 11. A picture inside the caves taken during the 1976 expedition

Plate 12. The Moricz Arch (formerly called von Däniken’s Arch), the gateway or portal dividing the two parts of the main Coangos cave

Plate 13. Cluster of sawed slabs of rock (Coangos Cave)

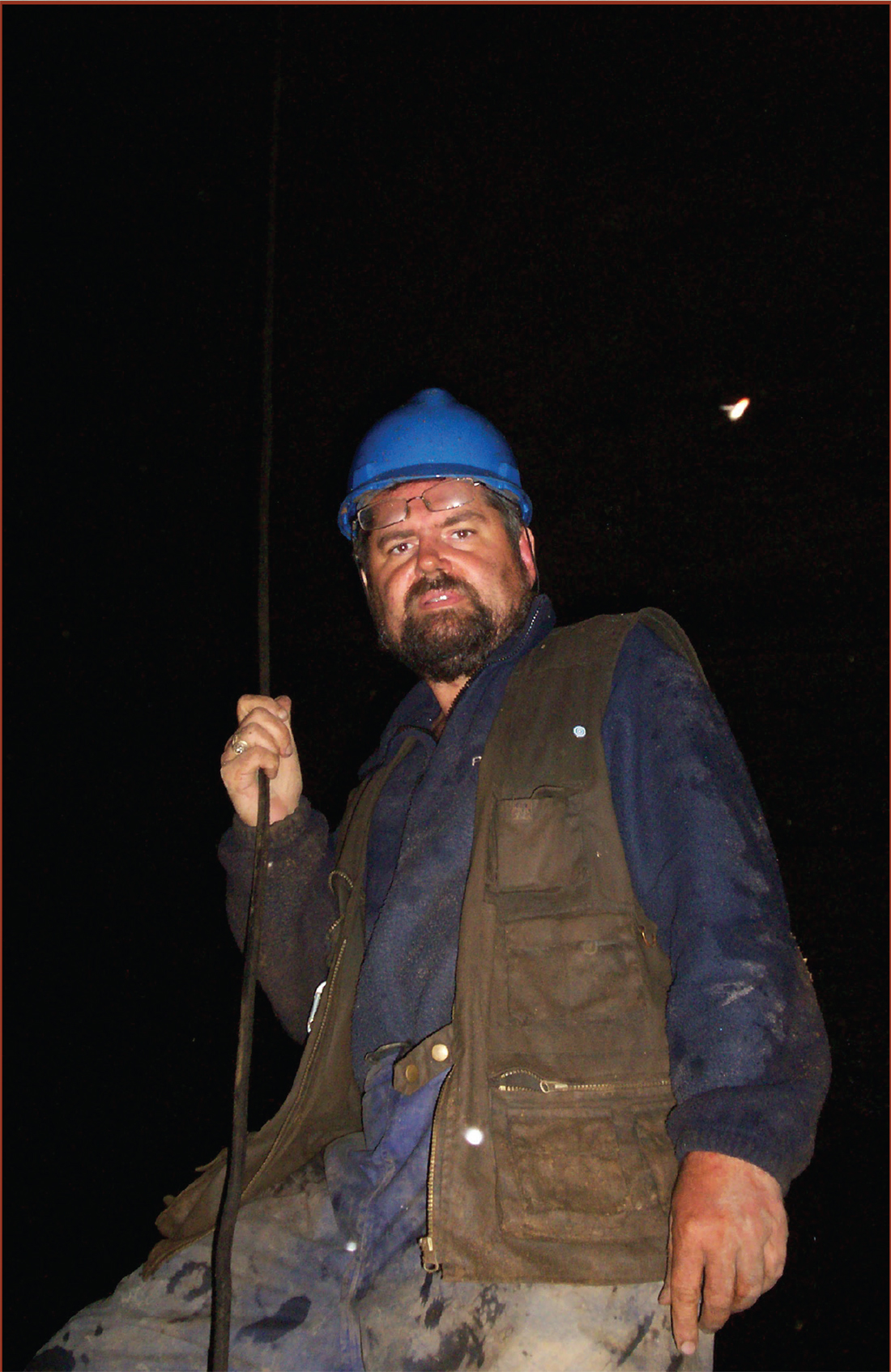

Plate 14. Descending and exploring the caves on the Sharupis’ land. Tayos caves system of the Pastaza River

Plate 15. The cascade (this image is from the Sharupis’ land in the Paztaza River region)

Plate 16. Alex escaping from flooding in the Sharupi Cave

Plate 17. Three officers from the Group of Intervention and Rescue who were part of my team

Plate 18. The cargo and generator prepared to cross the jungle by mule

Plate 19. The Coangos Valley from Limón Indanza in Morona-Santiago province

Plate 20. Bridge over Coangos

Plate 21. Alex makes his way through the narrow ducts and tunnels of the Coangos Cave

Plate 22. Alex inspecting the eroded walls

Plate 23. Interior of the Coangos Cave

Plate 24. The ground floor of the cave, covered in Tayos eggs

Plate 25. Phosphorescent scenes inside the caves

Plate 26. Stone steps cut with laser precision

Plate 27. The cornerstone

Plate 28. The author before returning to the surface

Edwin Park explains the sensationalist version in a letter. Below is his testimony. The story von Däniken told was so fantastic no one would believe it.

Moricz made a sworn declaration that is not based on true facts, it abused the Ecuadorian government and Dr. Peña; he made a huge drama telling the story of the lateral entrance we visited together. The scandal came with my book! It included the photographs Moricz gave me, and in it I described what we found in the tunnels.

Do you find this behavior to be new? I don’t. Moricz was repeating his ambiguous conduct.

The document that von Däniken mentions does correspond to the protocol deed submitted by the explorer in 1969, which stated:

We, the undersigned, members of the expedition to the caves discovered and claimed in Ecuador by Mr. Juan Moricz, formally agree not to give any declarations to journalists, radio, television or any other similar media, nor to publish any photographs. . . . Only the discoverer Mr. Juan Moricz, in exercise of his rights, will be able to release from the obligations and limitations established in the present document any of the undersigned when he deems it appropriate.

But thanks to Erich von Däniken’s best seller The Gold of the Gods, the Ecuadorian mysteries came to life. Tunnels, gold, statues and statuettes, collections lost and found all came together to create an almost legendary image of a land of magic, wild loneliness, genius, and cruelty. Von Däniken wondered if the writing on the plates was writing from the dawn of humanity.

An article in The Telegraph spoke of plates with sound systems and incomprehensible drawings. At some point von Däniken thought of Enoch and also of the connection between this book and the Mormons. Zecharia Sitchin connected them with the Eter-Efi and Enki.

Von Däniken studied similar religions since 1959, when he began his planetary search for the astronaut gods. “Being in front of Moricz and his Tayos I learned to be amazed again, I had seen these crazy descriptions of Moricz in other cultures and geographies. I was amazed then,” said the Swiss author, “and am amazed again when I remember those experiences. There are pretty old artifacts in some places of our planet.”

Moricz, who never finished writing a book, said, “Maybe future expeditions will let us see this, maybe someone will write a revolutionary book about all this. The foundation of all religions may have come from South America. This book must come out at the same time in many countries.” Von Däniken told him this was practically impossible.

“He also talked to me of a secondary entrance,” von Däniken continued, “but I had to swear not to divulge its location. There was a river. Moricz got out of the car and looked around him. ‘It’s up there,’ he said pointing to some rocks with vegetation. There was an entrance to a cavern, a black hole, and we sat down. Moricz had a square lamp. Peña Matheus took a picture of us there, the famous picture on the book cover. We crawled on all fours through the cave, where we could hear water running. I left my camera outside, with the priest and a child looking after it. We went into the cave, and I remember I saw some stone figures and some metallic plates I illuminated with my lantern. When we got to Guayaquil, I asked for the pictures from 1969 to use them in my new book.”

Moricz and Peña Matheus forgot to mention that those photographs he gave to von Däniken were not his, but were taken by two members of that expedition, by Hernán Fernández Borrero and the photographer for the second expedition, who managed to take better pictures.

Although von Däniken made up his own expedition using the pictures he took of the artifacts in the Crespi museum, von Däniken’s book was important because it showed the Father Crespi Museum to the public for the first time and brought Moricz’s story back to life.