12

From Scotland with Love

The Parallel Lives of Stanley Hall

Stanley Hall was born in Scotland. He fell in love with Moricz’s story as told by von Däniken in his book and then fell in love with Ecuador. With him the opportunity to solve the mystery was in the best hands, because he got to Ecuador with the purpose of rescuing the mysteries of the Tayos Caves for humanity.

But intrigue and distrust had turned Moricz into a very skeptical person, partly because he was very territorial, and because the person who came to ask an audience and license to find the treasure was a Scotsman who was a noble and an explorer, but who also represented an empire known for its scheming.

We don’t know how Stanley Hall’s destiny came to be as mysterious as Moricz’s or Aguado’s destiny. Hall insisted on continuing the search for the treasure, for the lost page of prehistory, much in the way Moricz always said: “Either this is simple, or impossible.”

Hall began writing letters to Gerardo Peña Matheus, telling him how he wanted to meet Moricz, but there is no doubt that when he arrived in Ecuador in 1976 his objective was to do an expedition to find the gold of the gods.

When he finally met Moricz, they talked for eighteen hours straight. This is when they realized they both believed Immanuel Velikovsky’s theories of archaeological evidence for environmental catastrophes, which showed that Hall had a theory he had to confirm, and that, like the other protagonists of the story, he believed he had a duty to fulfill.

The conditions Moricz set for the English expedition were similar to those he had set for the Mormons:

- the creation of a national board of notaries,

- the presence of international witnesses who would testify to the findings,

- that he was to be granted the leadership of the expedition, and

- that none of the artifacts found could be touched or moved.

Here I also need to quote a memo from the Ministry of Defense dated July 29, 1976: “There is not only one ‘Tayos Cave,’ but several caves along our eastern territory in El Coca, next to the Palora River, in Yaupi, in Coangos, and in Zamora-Chinchipe, all of them east of the third range of the Andes. The day Ecuadorians learn the true history of their country and of America, they will see the great importance the ‘center of the world’ had in the past, and everything this continent gave to the civilizations on Earth.”

Stanley—as his group of Ecuadorian and European friends called him—always believed that the fabulous illusion of the treasure of the Tayos could have been a tangible reality. He moved to Ecuador for it and later formed a family with someone who to this day defends and perpetuates his ideas. Remarkably, he managed to organize the largest speleological expedition of the twentieth century, and perhaps of history, in less than two years. Below is the official report of the 1976 expedition.

THE SCIENTIFIC REPORTS OF THE EXPEDITIONS OF 1976 (ECUADORIAN/BRITISH/SCOTTISH EXPLORATORY REPORTS)

Speleology

The Lost Tayos Cave system has everything for the speleologist: Waterfalls, huge tunnels and chambers: sporting feeder streamways and boulder falls of mountaineering proportions.

The cave system was a pleasure to explore, photograph and survey and ranks equal with the most famous of South American caves.

With the surveyed lengh of 4.9 km Los Tayos is one of the longest systems in South America.

The through trip from the “Cueva Commando” to Los Tayos is one of the most exciting and probably the deepest of its kind in South America, reaching a depth of 186 meters below the entrance of the cited Commando Cave.

The development of the system is classic in that the river which formed the cave has cut down through the sandstone to sink progressively further and further up its stream bed.

The original and oldest stream sink is the Archaelogical entrance which is in line with the main shaft and stream bed. The water now sinks in rubble over one km up the bed.

The “Commando” stream sinks just a few meters above the entrance, and although a completely distinct stream, the two beds come so close to one another that it is difficult to believe that in the past, particularly in times of flood, the Los Tayos and Commando streams did not join.

In this way “Commando Cave” may be considered as a more recent upstream sink for the “Los Tayos” cave system.

We did not have time to confirm the hydrological links proposed on the survey.

The hydrology is complex, with streams splitting, sumping (filling the passage to the reef) and reappearing at frequent intervals. However, there appear to be three main streams entering the cave system. One, the Los Tayos stress, we must assume enters the system in the M6 inlet series.

The Commando water enters “Snovel pot” and promptly sumps. We propose that this stream also enters the M6 series, near the Cascades. However, it may also account for other inlets in that area of the cave.

The third stream, which we think now (having drawn up the survey) to be completely distinct from the Commando and Los Tayos sinks, enters the “After Dinner series” at an impressive 30 m waterfall which we did not manage to bypass. This proposal is of necessity tentative.

The geological controls on the development of the “Los Tayos” system, are striking. Possibly the most obvious of these, on entering the cave, is the variation in thickness of rock strata from the entrance to the lower parts of the cave. Generally near the surface the limestone is massively bedded, with only thin layers of shale between beds.

The passages trend down, dip along a series of roughly parallel major joints, and pass out into unstable rock. In many of the lower passages there appears to be more shale than limestone and what there is of the latter is very muddy. The beds are thin and the passages show evidence of considerable collapse.

However, the situation is not simple, the dip and strike change considerably throughout the cave systems so that passages at similar levels below the surface are in different strata.

The rock is folded and possibly faulted, one case in mind being along the M6 series which appears to run along a fault with small vertical displacement.

Throughout the cave system collapse is evident in passage size dependent on whether or not collapse is present. The cascade inlet passages change from narrow vadose canyon type to large box section passages within a few meters, as a result of collapse. In the large entrance tunnels of Cueva de los Tayos passages are often of square section due to collapse.

As collapse proceeds the roof enters thicker and thicker beds and large gently dipping flat roofs result.

Because of extensive collapse there are few calcite formations in the cave and little evidence of flow markings from the streams which formed the cave.

Most of the passages are of vadose canyon type, although occasionally phreatic half tubes are present in the roof. Phreatic conditions probably indicated development before the gorge of the Rio Coangos cut down to its present level. However, since that time vadose development (passage enlargement by fast-flowing streams) has been the principal force in passage formation.

A number of features are of particular note within the system. The central Tayos chamber is of massive proportions due to collapse, and the roof goes up through the strata. However, at the upper end of the hall in the higher more massive limestone beds is an impressive phreatic feature, the Dome. This is a round, blind hole in the roof similar to the North American dome pits.

A massive reminder of the cave’s phreatic origin. “Shovel Pot” gives an excellent example of the effects of collapse. The entrance passages are low and epi-phreatic, but a bedding plane leads suddenly to a massive collapse chamber, developed a major joint and quite out of character with the other passages. The Staircase and Amphitheatre cut down steeply through the beds and show the gradation in bed thickness very clearly.

The small active passages leading to the sump are steep and sporting, yet connected closely with huge dry collapse tunnels. These small passages may well be stable despite the presence of the soft shale strata, and they lead to the sump pool, which is perched well above river level due to collapse and the in wash of debris.

There is a little chance of bypassing the sump, but there are passages within the system which with effort would yield further extensions. The two of particular note are a narrow rift and pitch in “Shovel Pot” and an artificial climb in the “After Dinner” series, to bypass the waterfall.

Both require special equipment and are well beyond the regions explored by the Indians, in search of the oilbirds. It is however to the credit of the Aboriginals that they explored well into the cave.

The vine ladder on the 50 m entrance shaft impressed fearlessness upon us and some of their tree trunk traverses were positively frightening.

Here we have only covered the processes of cave development and the physical nature of the system.

These brief notes are only a small part of the fascination of this impressive cave and all of us were equally intrigued by the rich life of the cave.

The biology of the system is part of the whole cave story, the study of which is of undying interest of us all.

Radiocarbon Dating

Radiocarbon has for more than 20 years been the major analytical tool available to archaeologists, providing ages for organic matter recovered from excavation, for example: bone, charcoal, peat and shell.

The accuracy of a single radiocarbon date depends on several factors, including sample size, and under optimum conditions plus or minus 60 years is a reasonable uncertainty.

My role in the “Tayos Expeditions” was to assist the archaeologists and to collect samples for C 14 analysis in the Nuclear Geochemistry research laboratory at the University of Glasgow.

A supplementary project was to collect speleothem samples from the caves. Stalactites and stalagmites can be dated by the Uranium-Thorium method, and oxygen isotope analysis can give information on paleotemperatures.

Speleothmem analysis is hopefully to be carried out by Dr. A. E. Fallick, Mcmaster University, Hamilton, Canada.

The excavations at the Tayos cave site did not provide any datable materials, however a “peat” sample taken from a depth of a 2 m may possibly yield an estimate of the rate of accumulation of guano.

Two sites of archaeological interest were located at the Mission of Santiago, approximately one mile east of the Teniente Ortiz base. The first site was at the site of the mission, and pottery and charcoal samples were collected. It is hoped that the pottery will be reconstructed to its original form. An intuitive estimate of the age of the site was from 500 to 1000 years before the present (B.P).

The second site appeared to be considerably clearer than the first, perhaps about 3000 years B.P, the estimate being based on the decoration on the pottery, which was similar to the recovered samples at the coastal sites.

Charcoal samples were collected from the controlled stratigraphic section, and hopefully the dates will establish a chronology of the area.

One interesting feature of the archaeometry will be direct comparison between age estimates obtained by C-14 analysis and thermoluminescence methods used by Dr. Nejdahl and the National Museum of Antiquities from Scotland, Edinburgh.

JOHN CAMPBELL

Studies on the Oilbirds (Los Pajaros Tayos)–Steatornis caripensis

Reports from the local Indians stated that they normally harvest young oilbirds from the Tayos caves’s system during the month of April.

In 1976—500 birds were reported taken from the caves. From work elsewhere on the species on average a little over 2 young are reared per pair.

This indicates that approximately 1,100 adults have reared 500 young taken this year. As many nesting ledges are too high for the Indians to exploit, there are probably in the region of 1500 to 2000 adult oilbirds breeding in the caves.

The very large deposits of seeds in the caves which have been regurgitated by the oilbirds after digesting off the pericarp (the nutritious part of the fruit) confirms that there is a large breeding population.

During the period the expedition was at the Tayos caves (6 July to August 3) the breeding season of the oilbirds was apparently coming to abrupt and with a number of young oilbirds failing to fledge and falling from their nests in a half-starving state weighing only one third of the expected weight, judging from the other stages of development.

Only a small percentage of the breeding population remained in the cave. 156 adults were counted leaving the cave for their nightly foraging on 14 of July, with approximately 10 to 15 remaining in the caves to tender and younger age.

This number dropped in a single family of young and their parents still present on 24 july, my last visit inside the cave. A final count of adults leaving on this evening of August 2 produced only 13 birds. While it is possible that the low numbers were partly due to disturbance at the cave the fact that the Yaupi caves were empty of oilbirds when first visited by members of the expedition on 24 of July suggests that it may be normal for the oilbirds of the area to desert their breeding caves at the end of the breeding season. This may be due to the large number of alternate caves in the area. In this behavior they differ from the species in Trinidad and Venezuela where breeding adults inhabit their nest sites throughout the year.

Large samples, from different points in the cave, of the seeds regurgitated by the oilbirds showed that the following proportions of fruit were normally being taken from the trees of the surrounding forests:

48% Palm fruits, Palmaceae

45% Mountain incense, Dacryodes species, Burseraceae.

7% Laurels, Lauraceae, and another unidentified discotyledon.

Three samples totaling 432 seeds, regurgitated during the period of the expedition, showed rather different proportions:

92% Palm fruits

8% Dacryodes

Less than 0.5% Laurels

Nearly all the Palm fruits taken were a species of Euterpe with seeds no bigger than 10 × 10 mm, and not extremely small compared to the bigger palms eaten much as Jessemia with a seed size of 38 × 23 mm. This is an indication of a very low fruit supply during the period of investigation probably causing the oilbirds to move elsewhere.

BARBARA L. SNOW

THE SEARCH FOR A LOST PAGE OF PREHISTORY

The question is: why would Hall and others continue to search the caves? Why go through all the trouble? Despite all the nonsense and hypocrisy surrounding this topic, it was clear to me that the purpose of the expeditions of 1969 and of 1976 was to find and take over the treasure, or at least to have the opportunity to see and photograph it. In this regard, both expeditions were complete fiascos, as Aguado confessed in a filmed interview in 1997.

In 1998 Hall was going to do a second part of his expedition, but this time taking Jaramillo to the place; he would have English funding once again. He also told me he had earned the right to the location of the metallic library, since he had spent seven years talking and building a friendship with Jaramillo. “I think I know the exact place where it is located. The future will tell if my calculations were right or not. I think people can’t critique my work if they haven’t studied my writing first,” Hall said.

I had studied him, I had even translated his web page and his description of the system he created called the Grailscope. I was very excited when I saw this name, because I thought it was an advanced detection device, but it was a system that synthesized logic with intuition using a database. He defined it as an interdisciplinary study of data from the Tayos Cave in relation to different disciplines such as geology, mythology, legends, religions, mysticism, philosophy, astronomy, and engineering.

I noticed Hall was a very polite person, and he didn’t dare contradict Jaramillo. I assume something similar happened with Moricz, although he was more inaccessible and elusive when the moment of truth arrived, which is why Moricz’s lawyer never dared ask him for material evidence of his discovery.

Hall also made some sense of the chaotic story of Jaramillo and told me what the original treasure would have included—or includes: “A library with thousands of metallic books, displayed on shelves that weigh approximately 44 pounds each. Each page would have ideograms, geometric designs and inscriptions on one side. There would be a second library with smaller, harder plates, but these are translucent, with carved parallel lines. Another hall would have statues of animals and zoomorphic figures in different positions. Metal bars with different shapes, next to a group of games and alluvial gold. An instrument to make buttons and simple jewelry. A sealed door, covered in semiprecious stones. In another one, a sarcophagus made of some translucent material [similar to quartz, but more transparent] that had the skeleton of a man covered in a thin layer of gold.”

When I asked why the existence of the library of golden plates was so important, he answered: “Not only do I believe with all my heart it exists, but beyond being a unique treasure, I believe it is a chapter of the history of South America, and a lost page of the book of prehistory.”

Until Hall’s death in September 2008, we had countless talks, and I interviewed him many times for international journals.

HALL’S CATASTROPHE THEORIES

In regard to the advanced constructions in the caves, Hall thought most of them were natural formations, and that some may have been improved by the Shuar. The official report of the 1976 expedition said:

The Tayos Caves are millennia-old mineral natural formations that have not been modified by men. They are a group of interconnected caverns or galleries that have different heights and widths, and a planimetric disposition that can be seen in the maps created by the technicians of the expedition.

In this report, and in several phone conversations, Hall insisted for several years that the formations were more natural than artificial. In a video interview from 2007—after my expeditions and testimonies—he held a more open position, where he was willing to consider the possibility that some artificial works could exist there.

In spite of his skepticism coupled with the open verdict of the geologists of the 1976 expedition, Hall had always been interested in the planetary catastrophe linked to Atlantis and the Andes. He liked the term Antis for the ancient population of the Andes; in other words, the Andean civilization that could have been destroyed by natural catastrophes. “The Andes today are very young in the geological chronology of the Earth,” he told me in 2005.

Hall thought the mythical story of the creation of mankind would include many keys to prehistory. One of his influences was Immanuel Velikovsky, the author of the classic book Worlds in Collision, who was one of the first people to talk about archaeological evidence of vast catastrophes. I was acquainted with Velikovsky’s daughter, who lived in Princeton, so I offered Hall an introduction, but I was surprised to see he wasn’t interested, even though at the time he was visiting the university for other reasons.

Stanley Hall was very similar to Velikovsky, but when the latter was mentioned, Hall never wanted to admit that he considered the father of planetary catastrophism to be wrong in Worlds in Collision. Even so, he followed that wave of mythic history and the relations between the solar system and humanity.

In the last years of his intellectual life, Hall catalogued and analyzed the history of interplanetary cataclysms, which happened when the planets were closer to Earth. These changes in orbits and planetary collisions with comets and asteroids, which caused cataclysms on our planet, were transformed by astrologer/priests into gods, goddesses, and angels, which would later be immortalized in words and stone. This is why many rulers are known as sons or daughters of the Sun, including rulers from the Egyptian and Incan civilizations.

For Hall, cosmology is mythology in action, and vice versa. As an engineer, he found similarities between the physical or geological world and the universe of legends, mainly creationism.

The Sun would erupt from other suns, or from a Great Star, leaving a trail of cosmic dust on the skies, which ancient civilizations would call Apsu Nun. Then the Sun ejected a great sphere of gas that would become proto-Gaia, which today is our Earth. The proto-Earth—or Gaia—gave birth to Ur-Atum, a creation myth that the Egyptians would develop over thousands of years. Hall believed Ur-Atum, proto-Uranus, was born from Gaia, the Earth goddess.

This might also explain how, for example, the mythical Titans, Cyclops, and Giants are large gas moons. The moons of Uranus— known as the Emperor of the Skies who was dethroned or defeated by the moons of Titan (pre-Saturn)—are captured in an orbit around proto-Saturn. The mythical Golden Age of Saturn came to an end when proto-Saturn was vanquished by his own descendant, Jupiter, whose serpentine tail would give rise to the myths of Typhon, Tiamat, and Ahriman. When Saturn created Jupiter, he also produced Neptune, Mercury, Mars, the moon, and comets.

Stories from the Arcadians, pre-Selenites, or Pirgios from the Mediterranean mention a period when the Earth had no moon, and when the messenger of the gods, Mercury (Hermes-Thoth), put the Earth in danger. Neptune, Saturn, and Uranus were cast farther out into the solar system as the netherworlds or Taieous, which Hall believed sounded a lot like the word “tayo.”

All the great mythologies of the world tell the same story with different names for the same planets. Today, the days of the week have the names of the seven solar globes, which is evidence of the evolution of those catastrophic impacts that happened before the solar system became stable.

A SUBSTITUTE GORDIAN KNOT

When Moricz died, Hall was left like a disoriented orphan who would not give up until he again found a line of history that he could hold on to in order to continue his restless search. This line would be as frustrating as the previous ones. Its name was Petronio Jaramillo Abarca.

Hall worked on this friendship because he wanted to be convinced that Jaramillo was telling the truth, and this truth could be in a different cave from the one Moricz had been showing to people since 1968. It was like cutting through a Gordian knot only to have to tie it up again.

The hardest question for the Scotsman—which had consumed all of the protagonists, including me—was if Moricz had deceived us all, even himself, by stating the real location (and paradigm) of the “Tayos Cave” was in one of the many caves nearby.

Those who believe in the “conspiracy” of the Tayos still believe that Hall was a member of international Freemasonry, and there is a rumor that his special guest for the expedition of 1976, Neil Armstrong, was also a Freemason. Hall and his official biographers always denied that the ex-astronaut was a declared or recognized Mason, but there is evidence that Armstrong was affiliated with the Mormon church.

The rumors usually cross over, settling on the contradiction of the presence of an American astronaut hero in a speleological expedition to search for a treasure that could be real or fantasy. This question has caused rivers of ink to flow and has created controversies all around. Armstrong refused several times to give me an interview that could have cleared up this recurring enigma forever. He always asked about my background and educational information. His official biographer couldn’t help me either. The weirdest part, and the biggest coincidence, was that the topic of the man on the moon was connected to the topic of the metaphysical conditions of Moricz.

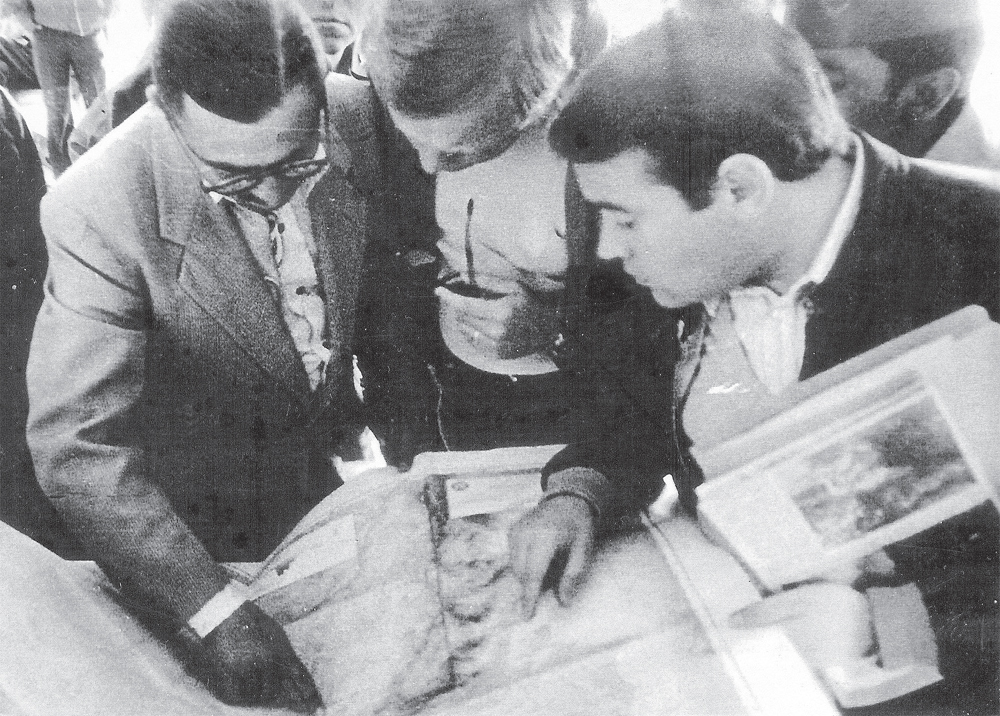

The president of Ecuador (left), Neil Armstrong (center), and Julio Goyén Aguado (right), checking a map of the region

Neil Armstrong poses with a stalagmite in the cave

During the 1969 expedition—which coincided with the first moon landing—two events mysteriously intertwined in space-time. And who would have thought the first man to leave his footprints on our satellite would be—just seven years later—part of the first international expedition of the Tayos?

Another unexplainable thing was what Moricz’s guide, Luis Nivelo, remembered. They were camping one night in front of the cave, under a huge full moon on July 17, 1969, when a strange shadow passed in front of the moon, to which Moricz reacted and predicted that one of the participants of the Apollo 11 mission would be a part of the upcoming Tayos expeditions.

Hall moved on, maybe hiding his apparent failure and recurring nostalgia in other projects that would justify so many years of expectations and illusions. As resigned as the Peña Matheus brothers, Hall continued thinking of the metallic library of the Tayos as the cornerstone of his life, always searching for a legend almost like the Holy Grail. He perpetuated it to exasperation and even boredom for himself and all those around him.

My research of the Marcahuasi Ruins led me to be interested in the Tayos, and my interest in the Tayos led me to Stanley Hall. This is how I became a part of that lineage of idealists and believers who would try to find an answer to the mystery of the Tayos. It didn’t take me long to go back to what I had left on hold in the early eighties, and then in the nineties, and organize a flash expedition that coincided with the twenty-year anniversary of the 1976 expedition. So in 1996 I went back to what I had first attempted in 1981–82: finding the Tayos Cave in Coangos.

MARCAHUASI: PLATEAU OF THE GODS

In the hour-long conversations we had before I headed to Coangos,Hall said he believed that, even if his superexpedition had been as methodical as possible, they could have studied the von Däniken Arch area more. He also told me I shouldn’t forget to take a good geologist with me to the expedition. I tried to invite Robert Schoch, who dated the Sphinx, and whom I had tried to take with me to the Marcahuasi Ruins, but the timing wasn’t right. For Moricz, the expedition of 1976 “tended to take over the clues of the Supreme Knowledge, maybe to destroy all evidence or hide it forever.” Perhaps this accounts for why it has been so difficult to pin down the exact location of the cave.

In spite of the first failed expedition to the Coangos region, Hall would alter the course of this structure to explore the area around the Pastaza River, which coincided with his new ideas. According to Hall, thanks to his Grailscope, he had found the location of Jaramillo’s stories, something that I would personally—and unfortunately—discover after two consecutive expeditions to the place.

The tenacity and drive to find the truth had already taken hold of me. They had been inside me for twenty-five years, when my expeditions to the Marcahuasi Ruins had driven me to look for archaeological and anthropological evidence to connect with the Tayos.

Marcahuasi is a plateau in the heights of the central Peruvian range, almost 13,404 feet above sea level. The plateau was rediscovered in the fifties by Daniel Ruzo, an explorer who is more interested in the esoteric than in archaeology. This plateau has some geological anomalies that would turn out to be sculptures from an unknown protohistoric race. Ruzo calls this rock building civilization the Masma and connects them anthropologically with the Masmudas in northern Africa, the Atlanteans, and the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel.

Marcahuasi, like many other places with mysterious ruins, and many constructions in Cusco and the surrounding areas, shows evidence of a rock polishing or softening technique. These rocks have been altered to create megalithic sculptures, as well as walls, halls, and surface and subterranean tombs.

Marcahuasi and the Tayos both have the peculiarity that they revolve around a legend of a lost ancestral library, probably dated before the Flood, and both are subterranean.

In 1993 I went down to the Infiernillo (little hell) tunnel, a peculiar part of the plateau with a large crack or fissure that is 82 feet deep. I visited a place that had accumulated sediment for thousands of years and that contained the royal tomb where maidens were sacrificed in honor of the local deity, the god Wallallo. This same character is represented on the surface, looking to heaven, and he seems to have a helmet that makes him look very similar to the controversial face on Mars.

During my explorations in the Marcahuasi Ruins and the Tayos Caves, I felt the tragic presence of something unknown, something cursed, even diabolical, that had been brewing for centuries, hanging over the shoulders of the protagonists or pseudoauthors of a dual myth that keeps slipping through our fingers, devouring its participants and coming back to life every so many years, always casting a different light at the end of the multiple tunnels—real or imaginary—that confirmed them.

My friends, who had been essential for my search, had died before, during, and after my expeditions. I almost got myself, and my brave colleagues, killed. All this happened after almost thirty years of chasing the same golden ghost. But in spite of it all, there was something—and there still is—that transcends all explanations and that gives us a different notion of existence and of the box we put around our limitless reality.

The main protagonists of the tragedy were gone, leaving us orphans, debating between truth and lies. I didn’t have a final answer to my question about whether Moricz had lied to Aguado, or if Aguado had lied to us, the idealists, the disciples of an enigma that helps create a new and hopeful view of the world. I didn’t know if they had lied to themselves, or if they fervently believed in those experiences that bordered on the metaphysical that they had in 1968, or if this experience had been the product of a plan to get revenge on the Mormons, who wanted to take the supposed treasure for themselves.

This might have even been a plan they repeated in a similar way when Moricz recommended Aguado as the guide to take Hall and Armstrong to the depths of a cave he wouldn’t have recognized himself, but that had some clues that could guide them to the chamber or sublevel that had the treasure.