India—with its tremendous richness of art, philosophy, and ancient sciences; its vitality in religious practices; its recent strides in modernization; its people intelligent and friendly along with those who beg, push to overcharge, or are just curious about foreign visitors; its ever-present dust, dung, and cows; its dense air and water pollution—continues to be a perplexing entity to me.

Through the burning August heat of 1988, my family and I stayed in Jaipur, a northern city with light-pink-colored brick palaces, houses, and town walls. It was originally planned and constructed by an astronomer, King Jai Singh, in the early eighteenth century. We then moved to, and settled in, another northern city, Varanasi, the most sacred city of Hinduism, which stands on the midstretch of the Ganges. Previously, in 1977 I had moved from Japan to San Francisco. It was there I met Linda Hess, a Zen student and scholar in Hindi poetry; we fell in love and got married in 1980. When we started to live in India in 1988, our daughter, Karuna, was six years old and our son, Ko, two.

On one bank of the curving Ganges River, down the steps under temple towers and faded plaster buildings, dozens of bathing terraces sit side by side. From dawn to dusk the shore is crowded with Hindus who dip themselves in the muddy holy water: sadhus wrapped in persimmon-colored cloths, holding a three-pronged stick in a cloth bag; women in saris; prosperous-looking men in white draped pants; workers in waist towels; and naked babies. A statue of a flying monkey, freshly painted with vermilion, stands in a shrine on a circular platform under a tree on the shore, attracting people who hang garlands of marigolds around its neck. Offering incense and ghee lamps, the devotees sprinkle flowers and water on the erotic stone symbols arrayed on the platform.

What had initially brought us to India was Linda’s research on Ramlila, large-scale performances of the Hindi version of the ancient epic the Ramayana. The task I had given to myself for our ten-month residence in India included studies of the Hindu concept of samsara, the continuous cycle of life, death, and rebirth, which is often explained as suffering. I had been trying to get a sense of how this common belief in reincarnation affected people’s lives there. Hoping to bring forth a glimpse of “life beyond” in my artwork, I had been doing sketches of the shorelines and waves of the Ganges, which is believed to swallow the karma of millions and wash it away.

Unfortunately, in my observations I hadn’t gotten any grip on samsara or life beyond or even just life. I reckoned the theme was too big. But, then again, what else had I done in my life other than being totally confused? I was rather enjoying this state of having “nowhere to go.”

A few blocks away from the shore runs one of the city’s longer streets, winding and bumpy, packed with peddlers behind their carts, and run-down sheds at its sides. Some people lie flat, sleeping on the pavement. Among the few new-model automobiles, swarms of scooter tricycle rickshaws roll along honking madly, and spreading toxic smoke. They dodge bikes, buffaloes, trucks, and pedestrians by a hair. Driving is certainly intuitive and unpredictable here. People fight for an inch by cutting in, making funny turns, and often driving on the wrong side of the street.

While I had been in California, the future world appeared to me as a clean and well-organized freeway where vehicles, operated by radar, would dart about at equal speeds without a chance of getting into accidents. At that moment, however, the streets in Varanasi seemed a closer image of the future, where people would inherit the outcome of the technology and consumption gaps of our generation, competing with one another in full anxiety and frustration.

As my heart went back and forth between “life beyond” and life in the world in this and the next generations, Linda and I tried to boil water to purify it, give our children private lessons, and send the errand runner to the post office, while at the same time searching for moments to work and dream of going out by ourselves.

As I contemplated doing artwork in Varanasi, my hope was to bring forth what might only be conceived of in India, and to use Indian tools and materials. Working in this way would require me to give up much of my usual way of seeing, as well as the techniques and styles of painting that had become familiar to me while living in Japan and the United States.

So captivating was homespun raw silk, matte and slightly brown, that after seeing it for the first time there I could imagine no other material on which to paint. There were a few large bottles of India ink in town. My fantasy to use old-style paints for miniature painting fell apart when I learned that there was nothing of that sort available in Varanasi, India’s capital of art. I did not have enough technical knowledge and patience, for example, to make yellow paint from the urine of a cow made sick by feeding on mango leaves, so I ended up with imported watercolors. I wish I could have said that a brush made of a bundle of peacock feathers was used on all my paintings, but in fact it was used on only one of them. I mostly depended upon European-style sable brushes purchased in Varanasi, but a white whisk, made of a wild cow’s tail for religious rites, did serve me as a brush. I additionally used a toothbrush, as well as a Tibetan coin, as painting tools.

What is most striking to me in Indian perspectives, or rather states of mind, is the way Indians look at time. Whereas futurists in other countries tend to discuss matters that will happen in ten or a hundred years, people in India seem to think in terms of samsara—many lives before and after this lifetime—a sense of which I sought to explore in the process of creating my series of paintings.

Before living in India, I would usually paint by swiftly sweeping a large brush, which was dipped in pitch-black ink, just once across one or more pieces of white paper. In this way, a lot of bristle movements would appear on the picture, allowing such “accidental” effects as splashes and drips. In India, however, I felt that expression of movement might get in the way in my Samsara series, where I intended to capture a sense of timelessness. When we view things on the scale of hundreds or thousands of years, there must be very little motion. So I decided to divide each picture into two parts—black and white—by a simple boundary line, either straight or curved.

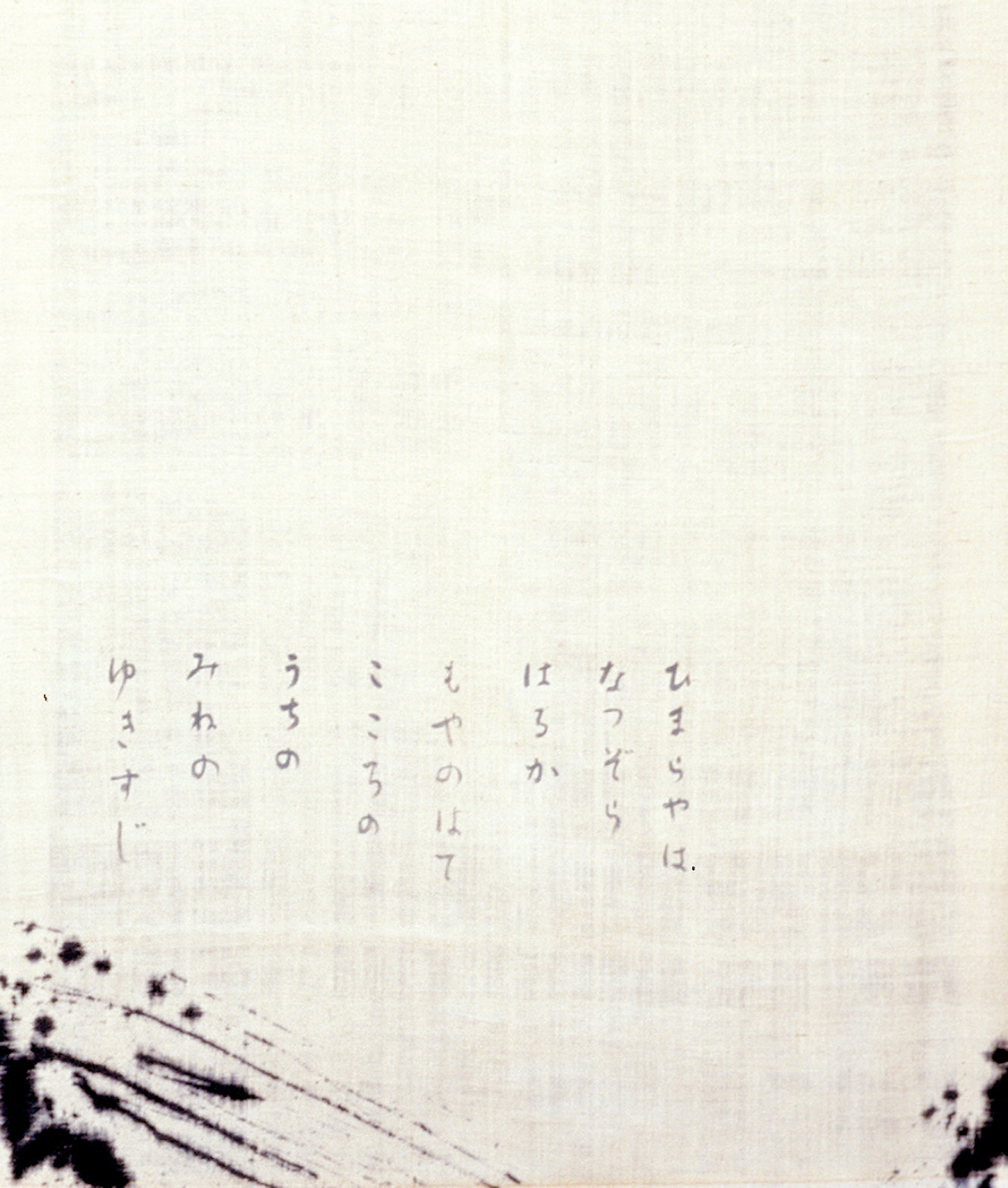

Samsara 10

In September and October 1988, I frequently visited the Ganges and made sketches of the water. Once at dawn, when I was sitting on the terrace of Tulsi Ghat watching people worship and bathe in the sacred river, a poem came to me. (This might give you the impression that I was always an early riser when, in fact, I went there before sunrise only that one time with one of our housemates, Manon Lafleur from Canada, who made sketches at the bathing shore almost every day at dawn.) The poem, which is in the waka form, may be translated from the Japanese as:

Day just breaking

Ganges riverbank

floating,

swirling

marigolds

In October and November about thirty waka poems fell on me. One late afternoon I hired a small boat and took my son, Ko, who had just turned three years old, from the highly populated west bank of Varanasi across the low winter water to the other shore where not a single soul abode—just washed-away bones scattered on the water’s edges.

Surrounded by vultures

dot by dot

shadows emerge

sand dunes

on shore

The vultures in the sky encircled us, and yet were completely still. It felt as if they were waiting for the death of somebody. It could have been the death of myself or my boy. Perhaps even the human race. It was a strange sensation, giving me a glimpse into time spans stretching beyond the realm of imagination.

In December I completed studies for seventeen paintings. Each of the actual paintings was to consist of a black and a white space as well as a poem inscribed in color. At this point I had a rough idea of how the space would be divided, with the poem placed in each of the thirty-two-by-thirty-seven-inch pictures. Making preparatory designs and studies was quite new for me, a one-stroke monochromist. I also used color for the first time in thirty years. My youthful practices of oil painting, copying ancient Chinese calligraphic masterpieces, and writing poems in Japanese all came together.

In January 1989 I started creating the final pieces. I wanted the black to be solid—a place where all things would merge and segments of time would dissolve. This would represent the darkness where no logic or dualistic thinking could reach.

While filling a large section of silk with a number of rough brushstrokes, I developed a fascination for the interaction of the black ink and the extremely sensitive Bengali textile. It then occurred to me that I should leave the brush marks as they were, instead of painting over the black portion entirely flat. Long, thin lines running in various directions would represent stars in the night sky; a number of dots stamped with small brushes would suggest millions of stupas; and overlapping spirals would be portions of continuous cycles of rebirths. Each block of darkness on the paintings came out differently, often with white openings seen through the black lines. Some blocks of darkness were almost white with slight suggestions of shadows created by a few brushstrokes.

Although I started out with studies that tried to represent ultimate darkness, during the process of creating the final pieces I found myself thrown into the realm of incomplete, contradictory, ambivalent shadows. These shadows, each having a unique texture, certainly did not represent the timelessness that I first intended to express. But this process of my working led me to suspect there are many versions of timelessness, and that we all have our own unique interpretations of nonduality: the oneness of all things.