A common notion of laziness is that it is counterproductive. I would say, however, there are cases in which the lazier we are, the more productive we become.

At times it’s good to slow down and be lazy, especially when there is so much strain on our body and mind to the point that our health is threatened. In fact, it is imperative to slow down when our body sends us critical stress signals.

In Japan there is a saying: “Living long is part of the art.” The healthier we are and the longer we live, the more chance we have to create and serve others.

Is it not uncommon for us to be so focused on goals that we cannot be free from anxiety until we reach the point of completion? The steps toward the goal remain partial as long as the goal remains unattained, so a drive toward fulfillment of the goal dominates our life.

In Brush Mind, an earlier book of mine, I suggested: “It’s a tough job to be lazy, but somebody has to do it. Industrious people build industry. Lazy people build civilization.”

I take this as a reminder to myself that I, along with the rest of the world, need to slow down. If we enjoy working so much that we forget to stop, then our health may be harmed. Those who are lazy on a regular basis don’t need such a reminder, but workaholics should try it for a change.

East Asian calligraphy is the main art that I practice and teach. The ideographic calligraphy has been a common art form for the Chinese, Vietnamese, Koreans, and Japanese. Some Chinese calligraphers are particularly known for their meditative brushstrokes similar to the slow movements of the traditional Chinese martial art, taiji (t’ai chi). You might find it useful to follow this aspect of art practice.

When you try to move the brush slowly for the first time, you might find it difficult to keep control of the brush movement. You might also experience a conflict within. Part of you may want to slow down. On the other hand, you may feel the urge to go back to your usual mode of doing things quickly in order to finish drawing and get it out of the way.

With time and practice, however, you would probably get accustomed to the relaxed pace, becoming aware of each subtle variable of the brush movement and its relationship to your body and mind. You might even come to love it and enjoy drawing each stroke. Each line, like the moment in which it was drawn, carries a timelessness and completeness of its own.

No line you draw has to be perfect. On the contrary, you may keep drawing clumsy lines. Of course you improve your lines little by little, but it’s rather unrealistic to expect to become a master right away. Yet, even if the line might be imperfect or not look so great, the act of drawing a line is complete. Regardless of the appearance of the product, we become free of struggling for accomplishment or creating something perfect.

If life is goal-oriented, as soon as one goal is achieved other goals appear; we become anxious for achieving goals most of the time. If, however, we enjoy each step of the way, each step in turn becomes the goal. We can enhance relaxation and the density of our life enormously.

Meditation is an excellent way to help us to enjoy being slow and doing less. The practice of a meditative art, such as yoga, the tea ceremony, and martial arts, can bring forth similar effects.

Laziness does not mean doing nothing but doing less. It can also mean being effective. (As I like to say, “I am too lazy to be ineffective.”)

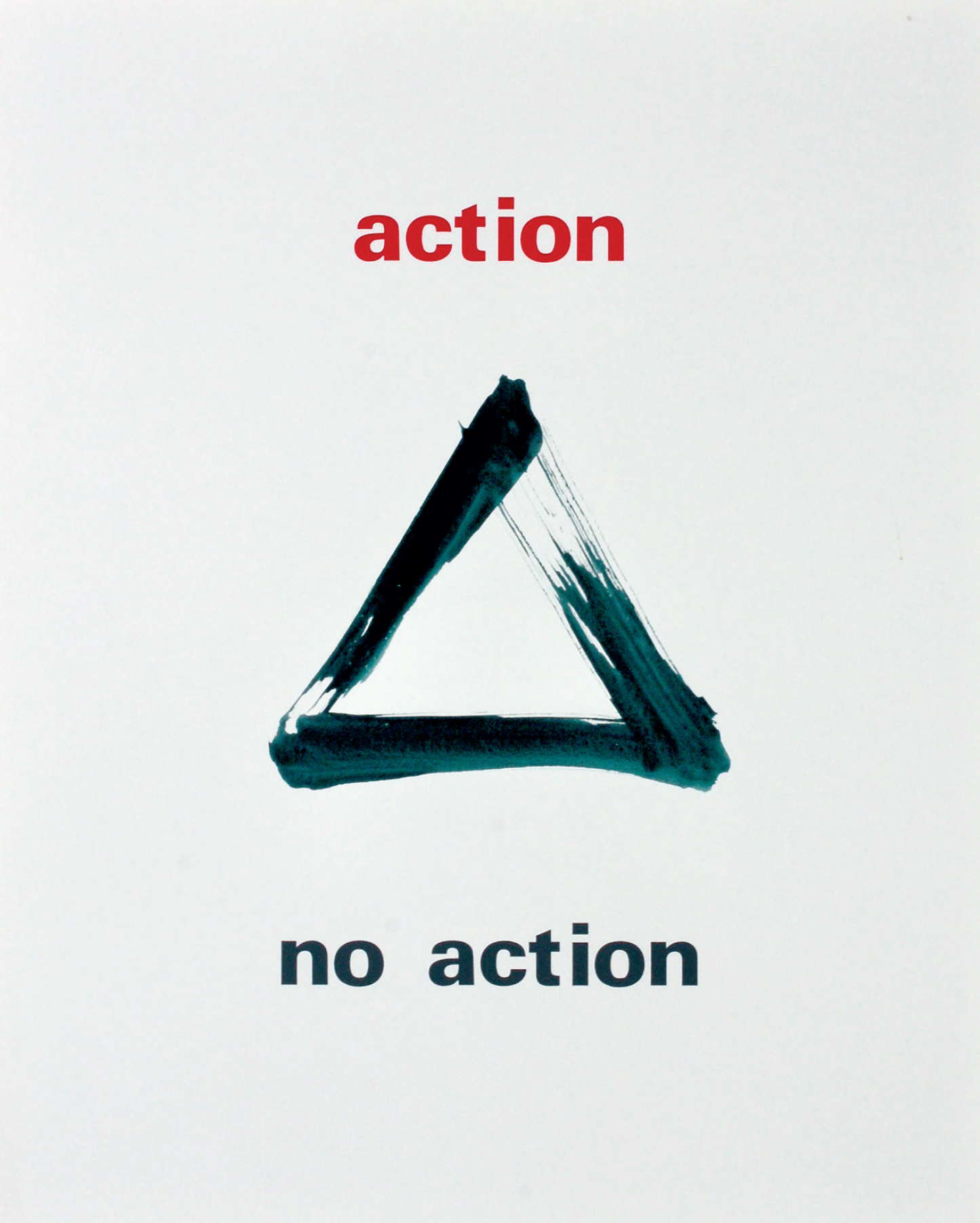

When you have a big project or when there is a crisis, you may want to take action immediately. But it may be wise to choose to do nothing for a while and contemplate the best way to deal with the situation. In this case, practicing no-action can be the best action. No-action contains boundless potential for action.

action/no action

The study of aikido in my youth with its founder, Morihei Ueshiba, has been my foundation for meditation in action. As I mentioned before, he would sit square on the wooden floor of the small dojo and let some of us push him as hard as we could. Instead of being pushed down he would relax, smile, and absorb all the incoming forces.

In this act, he showed us the power of physical and mental relaxation. In recent days, over fifty years after my lessons, I have come to suspect that he was demonstrating the most profound secret of martial art: the power of being immovable.

Some of the movements in aikido are spectacular—throwing the opponent in the air with no touching, or throwing down multiple opponents in one sweeping motion. We students were exposed to such miraculous maneuvers day by day. I had easily overlooked the significance of the master just sitting still on the floor.

Ueshiba taught me the value of both motion and stillness. Motion is all the actions we take in our lives. Stillness means total groundedness. It is not only the lack of motion but the foundation of it. Motion and stillness—busyness and laziness—are equally important. And because most of us are busy all the time and ignore laziness, it is beneficial sometimes to focus on cultivating laziness.

Once, someone invited me to participate in a peace conference. After meeting her some time before the conference and making the necessary arrangements, I asked her, “Are you having fun?” She said, “No. I have so many things to do. I have no time to enjoy myself.” I just looked at her with no remark.

Later she thought about our conversation and realized that it was not good that she was not enjoying the process of preparing one of the largest undertakings in her life. So, she and her husband took one week off and spent a restful vacation on a small island in Greece. I was impressed at the serene and graceful manner with which she conducted the conference.

When my colleagues and I were fully engaged in the work for Plutonium Free Future, I would say, “The most important thing about our work is how well each one of us is, and how much we enjoy our work. If we get sick, we cannot do the work. If we don’t enjoy the work, we should do something else.” This may sound self-centered, but in fact it is a way of becoming selfless, centered around laziness.

The power of doing nothing is amazing. You might think reading, watching television, or following a meditation schedule is doing nothing. But really doing nothing may be beyond any of these.

Suppose you are in a cottage in the mountains and do nothing except for drinking water, eating, doing exercises, and taking notes. You might be afraid of being bored. Yes, you would be bored all right. But remember: Boredom is the greatest companion of laziness. All creative thoughts and actions derive from a state of unstained boredom.

Some of you may be too lazy to find and go to a cottage in the mountains. If this is the case, try practicing ultimate laziness at an airport or in a train. It is guaranteed to succeed, providing you don’t miss your plane or leave your suitcase behind at the train station.