“Pain is in the brain” – not where you feel the pain – so it’s not always easy to know where pain messages are coming from. Sometimes it’s pretty obvious – if, say, you stub your toe or bump your head. But often the pain you feel in one place originates somewhere else. Your experience of pain combines messages received and managed by your nervous system – involving conscious and unconscious processes – with your responses to the pain, such as changes in your posture, behaviour or function. To better understand pain we need to take a closer look at the nervous system.

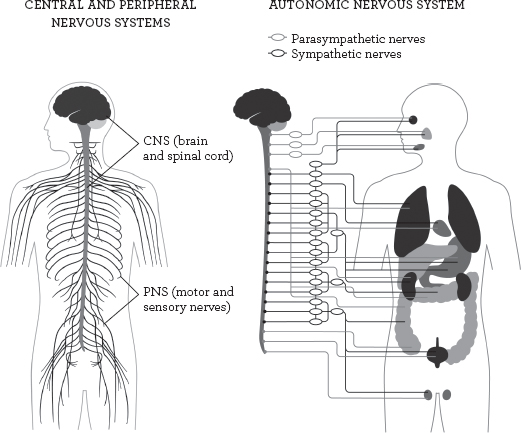

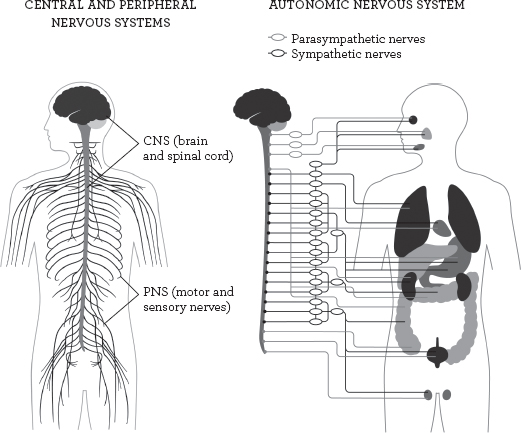

The brain and the spinal cord form the central nervous system (CNS) and this receives messages from the peripheral nervous system (PNS), made up of nerves that feel (sensory) and those that activate (motor). Those aspects of the body over which we have little or no conscious control are governed by the autonomic nervous system (ANS), and this is itself divided into the sympathetic and the parasympathetic branches, which respectively stimulate or moderate functions such as the rate at which you breathe or your heart beats.

Within these systems and sub-systems are a host of “reflex pathways” that help manage the astonishingly intricate functioning of the body. It is along these pathways that messages such as pain are referred from one area to another. For example, viscero-somatic pathways carry pain that originates in an organ to a more mechanical part of the body, such as angina pain felt in the arm. Pain travelling in the opposite direction (along a somatico-visceral pathway) includes that felt in the heart, but caused by irritated nerve structures in the chest muscles. Messages can also be transmitted from one movable part of the body to another. A simple example is the defensive reflex that tells your arm to move your hand when you touch something hot.

Pain felt in a part of the body may even have an emotional, rather than a physical, cause. An example of this psychosomatic pain is the stomach ache you might feel before an exam.

In some cases, a single event can give rise to more than one pain message travelling along more than one pathway. For example, if you were to fall and twist your back, the vertebra that you twisted would be painful afterwards, but you might also suffer pain in one of your legs. This referred leg pain might be caused by the vertebra pressing onto a nerve; or you might have irritated some nerve structures in the joints connecting the vertebrae to each other; or you might have altered your posture to compensate for the initial pain in your back, thereby triggering pain in your leg; and of course memories of past experiences might colour the meaning you give to this back pain, and how you behave as a result.

A remarkable aspect of all this confusion is that when researchers compare the progress of different back injuries of this sort, they find that, with or without treatment or medication, most of them are better within four weeks. The body usually heals itself. When it cannot, treatment is needed.

“Understanding pain physiology changes the way people think about pain, reduces its threat value and improves their management of it.”

David Butler and Lorimer Moseley, Explain Pain1