WHILE AMELIA WAS WORKING AT Denison House—before she had received that mysterious call—the flying world was soaring forward.

In the spring of 1927, Charles Lindbergh did the seemingly impossible, flying nonstop across the North Atlantic. His thirty-three-hour flight from New York to Paris made aviation history and turned Lindbergh into a national hero. Everywhere he went, he was greeted with marching bands and ticker-tape parades. He received the Congressional Medal of Honor and was paid the unheard-of sum of $125,000 (almost one and a half million dollars nowadays) to write a book about his adventure. No one was more famous than Lindbergh.

Charles Lindbergh in the cockpit of the Spirit of St. Louis, the plane he flew across the Atlantic. (picture credit 10.1)

And other fliers longed to follow. Yes, Lindbergh had already accomplished a great challenge, but there were still others out there. There was the challenge of flying across the Atlantic to the United States against the wind—a harder, longer trip than Lindbergh’s. There was the challenge of being the first to fly nonstop from New York to California, or nonstop from New York to Cuba. But the biggest remaining prize of all was to become the first woman to fly across the Atlantic.

In the year after Lindbergh’s flight, five women attempted to fly across the Atlantic. Two of them each took along a male pilot because they did not have enough experience to fly alone as Lindbergh had. But this didn’t matter to the public. The simple fact that a woman even dared to try caused great excitement.

Of the five women, two disappeared over the Atlantic, one had to be rescued at sea, and one never got her plane off the ground.

The fifth woman to try was the famous British aviatrix Elsie Mackay, who stunned fliers by taking off in March, when freezing temperatures still extended across the Atlantic. (In 1928, before the invention of deicers, ice was a plane’s worst enemy.) Days later, parts of her plane washed up on Ireland’s coast.

Who would try next?

Amy Phipps Guest decided she would. Wealthy, matronly, fifty-five-year-old Amy had never flown before. Still, she had a desire for adventure as well as a huge bank account. So, sparing no expense, she bought a plane from Commander Richard E. Byrd (who had used the plane on a flight around the North Pole) and sent it to an East Boston airfield so it could be fitted out for her flight. She told no one about her plans, not even her husband and children. The journey, she decided, would take place in May 1928. In her country estate in Roslyn, New York, she dreamed of making a dramatic landing, her plane touching down right in front of London’s Houses of Parliament. Amy named the plane Friendship.

But somehow, Amy’s family caught wind of her secret plans. They begged her not to do it. “You will end up floating in the ocean,” wailed her daughter, Diana.

Amy backed down. But she still wanted an American to be the first woman to fly across the Atlantic. “Find me someone nice who will do us proud,” she instructed her lawyer, David Layman. “I shall pay the bills.” She went on to insist that the chosen woman should be “a lady, college-educated, attractive, and, if possible, a flyer.”

“Is that all?” replied Layman sarcastically. He had no idea how to go about finding such a flier.

On the very day when David Layman was speaking with Amy Guest, the well-known publisher George Putnam was riding the Staten Island ferry. Putnam loved airplanes, and as luck would have it, he fell into conversation with a fellow passenger who just happened to be a pilot. The pilot passed on a fascinating piece of gossip: a wealthy woman had bought Commander Byrd’s plane and was planning a long, dangerous and secret flight. The plane, added the pilot, was being outfitted in Boston.

“I instantly saw the possibilities,” recalled George. “I had stumbled on an adventure-in-the-making which might provide a book.”

George returned to his office to find that his old friend Hilton Railey had dropped by for a visit. Railey was a Boston public relations specialist who also had an interest in airplanes. George couldn’t believe the coincidence. He repeated the gossip he’d heard on the ferry, then asked Railey to use his Boston connections to find out what he could.

Railey agreed. By midnight he had tracked down the plane and the name of the wealthy woman’s lawyer: David Layman.

George Putnam telephoned Layman the very next morning. “I pretty much dropped from the clouds and introduced myself,” said George. Layman, who was still struggling to find a female flier, eagerly accepted George’s offer to help.

Now George turned again to Railey. Did Railey have any Boston contacts who might be able to help?

Railey did—a retired admiral named Reginald R. Belknap, who was very involved in the Boston air world.

Railey asked Belknap if he knew of a possible candidate.

“Why, yes,” replied the admiral. “I know a young social worker who flies. . . . Call Denison House and ask for Amelia Earhart.”

A day later, Railey telephoned Amelia. “Would you be interested in doing something for aviation which might be dangerous?” he asked.

Intrigued, Amelia agreed to meet Railey at his office for an interview.

“How would you like to be the first woman to fly the Atlantic?” he asked her minutes after she’d walked in.

“Very much,” replied Amelia.

Ten days later, she was invited to another interview with Railey in New York City. This time, George Putnam, as well as David Layman and Amy Guest’s brother John Phipps, were there. (Having decided to leave all the details to her lawyer, Amy Guest wasn’t present at the interview.) The men “rained questions upon me,” remembered Amelia. “Was I willing to fly the Atlantic? What was my education? Was I strong? What flying experience did I have?”

The men were taken by her answers, as well as “her infectious laugh, her poise, warmth and impressive dignity.” Additionally, they couldn’t help noticing that Amelia looked enough like Charles Lindbergh to be his sister. “An added bonus, publicity-wise,” remarked George.

Still, George was curious. “Why do you want to fly the Atlantic?” he asked her.

Amelia looked at him a moment, then smiled. “Why does a man ride a horse?” she replied.

“Because he wants to, I guess,” answered George.

Amelia shrugged. “Well, then.”

George laughed, and Amelia joined in.

Two days later she received a note from Mrs. Guest. “You may make this flight if you wish,” wrote the older woman.

Recalled Amelia, “I couldn’t say no.”

This photograph of Amelia and George Putnam was taken in May 1928. He was, recalled one friend, “already mad about her.” (picture credit 10.2)

Amelia was made captain of the flight. This meant she would help make decisions, as well as keep the plane’s log. But she would not take the plane’s controls. This would be Bill Stultz’s job. A skilled aviator, navigator and radio operator, Stultz had been hired as pilot months earlier. Lou “Slim” Gordon, a mechanic with years of engine experience, would also be on the flight.

Preparations for the trip were top-secret. “If it was known that a woman was trying to fly across the Atlantic, the airfield would be overrun with crowds,” explained George.

Besides, they worried about competitors. “We didn’t want to instigate a race,” wrote Amelia. For this reason, she was asked to stay away from the airfield. “I did not dare show myself around the airport,” she said. “Not once was I with the men on their test flights. In fact, I saw the Friendship only once before our first attempted take-off.”

It was mid-May 1928 when she saw the plane for the first time—a Fokker with gold wings and an orange body (colors easy to spot if it went down in the sea). The Fokker had three 225-horsepower engines, two fuel tanks that could carry almost 900 gallons of gasoline, and pontoons in place of wheels so it could take off and land on water. Amelia thought the plane was beautiful. “Its golden wings,” she wrote, “were strong and exquisitely fashioned.”

While the plane was being readied, Amelia went on working at Denison House.

Even though she was sworn to secrecy, she didn’t want to head off on such a dangerous journey without leaving some final word for her family. She decided to write farewell letters, “just in case.”

To her father she wrote: “Hooray for the last grand adventure. I wish I had won, but it was worthwhile, anyway.”

To her mother, she said: “My life has really been very happy, and I didn’t mind contemplating its end in the midst of it.”

And to Muriel, she wrote: “My only regret will be leaving you and Mother stranded.”

The Friendship in flight. (picture credit 10.3)

While Amelia made preparations in case she died, George Putnam was making plans in case she lived. Arriving in Boston to personally take charge of the publicity, he sold Amelia’s story rights to the New York Times and worked out a deal with Paramount Pictures for exclusive newsreel coverage of her takeoff and landing. More important, he hired Jake Coolidge, a renowned photographer, to take “a great bunch of shots” of her. George knew her photograph would be in demand if she succeeded.

“Lady Lindy”—one of the publicity shots taken by Jake Coolidge just before the transatlantic flight. Coolidge deliberately photographed Amelia in outfits similar to those worn by Lindbergh—leather jacket, white-edged helmet, riding breeches and goggles. He even used the same poses as those found in Lindbergh’s most famous photographs. In the end, Amelia’s resemblance to Lindbergh was uncanny. (picture credit 10.4)

In his spare time, George got to know Amelia better. He took her to restaurants and the theater. In return, she took him for rides in her sports car, which he dubbed the yellow peril because of her haphazard driving. He took to calling her A.E. She nicknamed him Simpkin, after the cat in Beatrix Potter’s story The Tailor of Gloucester. Together they discovered a mutual passion for speed, adventure and Chinese food.

“George was a fascinating man to Amelia,” recalled Muriel. “He had been to the Arctic, was personal friends with some of the century’s greatest explorers and adventurers, was handsome and intelligent.”

Amelia fascinated George, too. He admired her poise, her dedication to hard work, her enthusiasm for airplanes. “He set about romancing her,” recalled a friend, “with charm, wit and gifts.”

One of those gifts was a leather-bound diary trimmed in gold and inscribed:

A.E.

From

G.P.

5/15/28

She would use this gift to record her thoughts and feelings during the flight.

Amelia obviously had romantic feelings for George, too. But she resisted his charms at first, because George was married. His wife, Dorothy Putnam, knew all about her husband’s friendship with the pretty young pilot, and she fretted about it. “The minute he laid eyes on Amelia Earhart,” Dorothy said later, “he had eyes for no one else.”

By late May, everything—the plane, the crew, the publicity—was in place. It was time to fly. But two attempts to take off from Boston failed because of bad weather. When the Friendship finally did take to the air (on June 3, 1928), it headed up the coast and into a thick fog. Since instruments for flying blind had not yet been invented, the crew looked for a hole in the fog and landed in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The next day, with the skies clear again, they flew to Trepassey, Newfoundland. This was the jumping-off point for their trip across the Atlantic.

But days of strong gales and thick fog made takeoff impossible. The fliers spent the next week playing cards and growing more and more dispirited. Then George cabled with more bad news.

Their delay had opened up an opportunity for other female pilots. Hours earlier, Mabel Boll had announced her intention to start a transatlantic flight within the next few days. And in Germany, the aviatrix Thea Rasche also announced her plans to cross the Atlantic. Wrote Amelia in the plane’s log, “our competitors are gaining on us.”

She had to chance it. Bad weather or not, she decided, they would go.

The next day, June 12, the determined crew climbed into the Friendship. For the next four hours they battled to take off. But the “receding tide made the sea so heavy that the spray . . . drowned the outboard motors,” wrote Amelia. “We are all too disappointed to talk.”

The crew tried again the next morning, but still the weather made their efforts useless. “The days grow worse,” Amelia wrote. “I think each time we have reached the low, but find we haven’t.”

To make matters worse, Bill was drinking heavily. Amelia lectured him about it, but he refused to listen. “There is a madness to Bill,” she wrote, “which is not in keeping with a pilot who has to fly.”

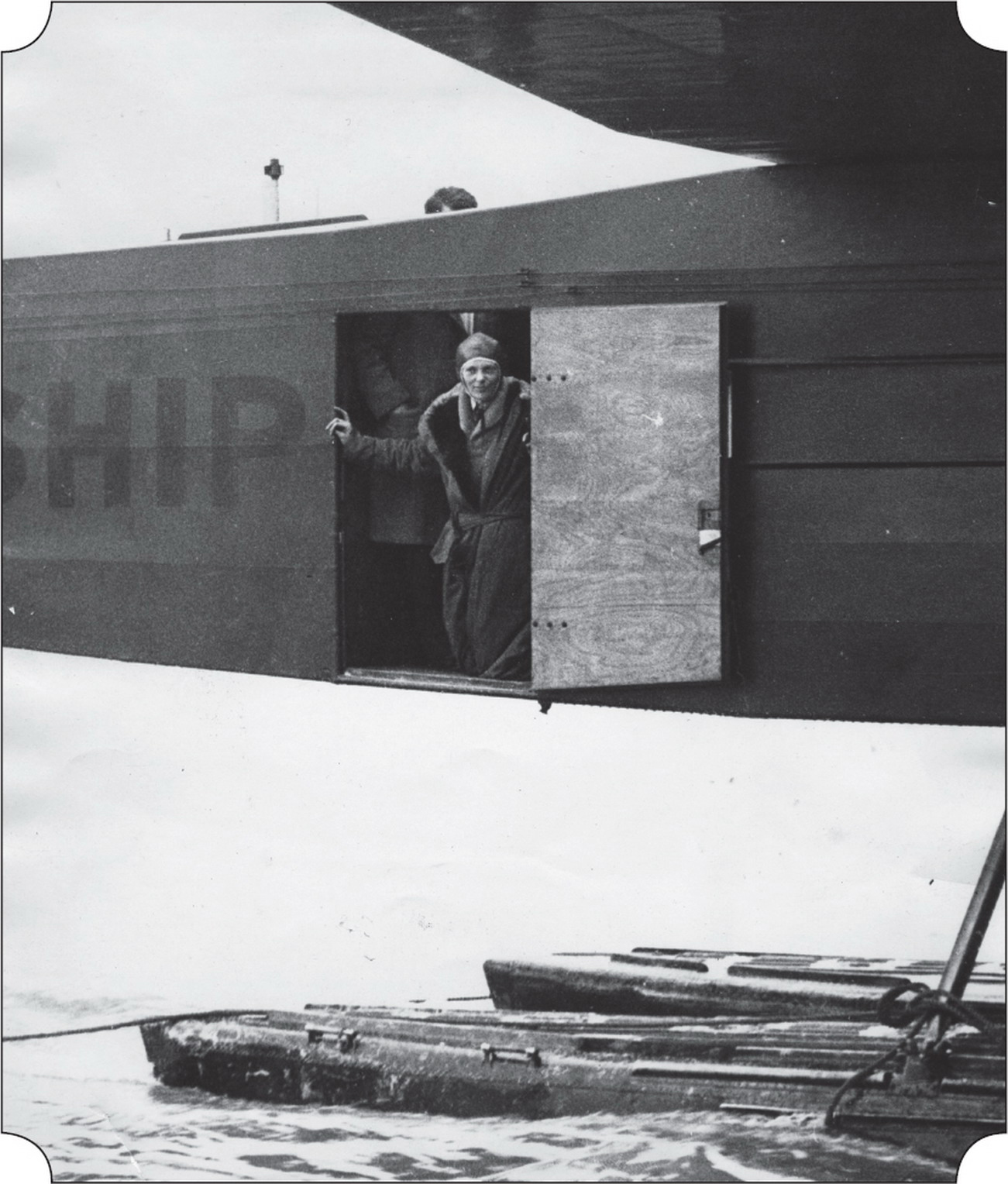

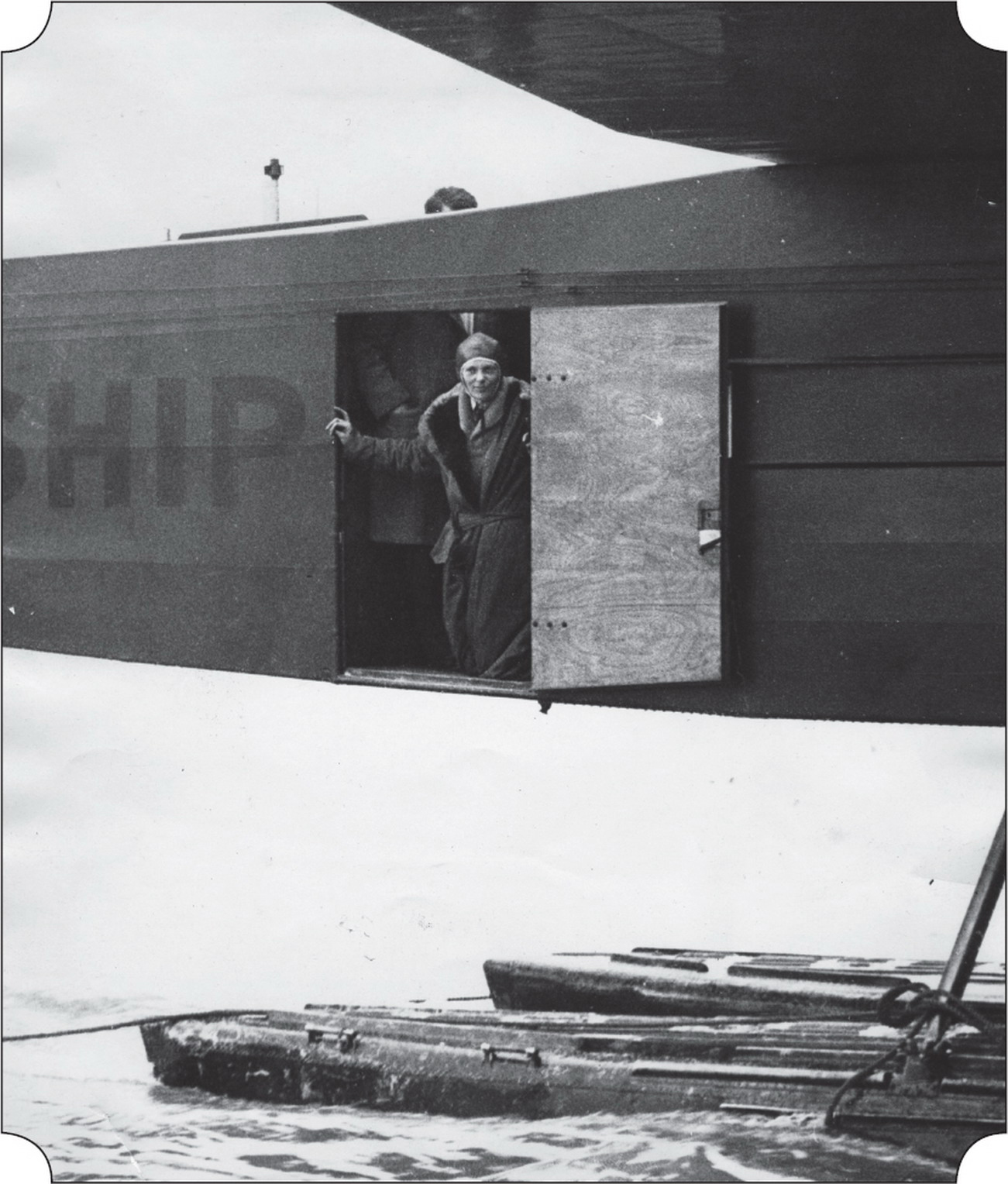

As captain of the flight, Amelia remained in the plane’s bare cabin. It was so cold, she ended up wearing a fur-lined suit over her flying clothes. (picture credit 10.5)

Finally, on June 17—after twelve days of waiting—the weather calmed a bit. “We are going today, and we are going to make it,” Amelia declared. The problem was, Bill had been out drinking the night before and was in no shape to fly. Amelia spent hours pouring black coffee into her pilot in hopes of sobering him up. “She knew the start had to be made then or probably never,” recalled Slim Gordon, “so finally, she simply got hold of her pilot and all but dragged him to the plane.”

Slim cast off the mooring lines; then the plane taxied slowly across the choppy waves. But once again, it failed to take off. In the blustery winds, the aircraft was too heavy. So Amelia made a desperate decision. She ordered them to dump gasoline—all but 700 gallons. This meant that the fliers would have barely enough fuel to get across the Atlantic Ocean. Instead of landing in London as originally planned, they would now have to head for Ireland and hope they didn’t get lost along the way. They simply didn’t have enough gasoline to make any mistakes.

Finally—rocking and bouncing, its outboard motors sputtering from salt water spray—the Friendship staggered across the waves. In the plane’s cabin Amelia crouched, stopwatch in hand. She was “checking the take-off time, and with my eyes glued on the air speed indicator as it slowly climbed. If it passed fifty miles an hour, chances were the Friendship could pull out and fly.

“Thirty—forty—the Friendship was trying again. A long pause, then the pointer went to fifty—fifty-five—sixty. We were off at last!”

They climbed to 3,000 feet and ran into fog. They climbed higher and met a snowstorm. Then Bill headed down, and they broke into clear skies and sunshine with a blue sea below them.

But not for long. The fliers soon found themselves in dense fog. “Not again on the flight did we see the ocean,” wrote Amelia.

Unable to determine their course by sight, they hoped to rely on their radio. But somewhere over the Atlantic, the radio broke again. The Friendship could not get word from ships at sea to check their position. As the hours of flying continued, the tension aboard the plane increased. Their fuel was rapidly dwindling. If they were off course, they would be in serious trouble.

With only one hour’s fuel left, Bill dropped down through the clouds. Below them they saw a ship. Bill circled it, hoping its captain would paint the latitude and longitude on its deck (a common practice in those early aviation days). But the captain didn’t. So Amelia wrote their request on a page torn from her logbook. She tied the note to an orange, then dropped it through the hatch in the cabin floor. It missed the ship and sank into the sea. So “we tried another shot,” said Amelia. “No luck.”

With their fuel now dangerously low, the fliers considered giving up and landing in the sea near the ship, where they would be picked up. Then Bill stubbornly declared, “That’s out!” And he swung the plane back on course and kept straight on.

Minutes later, out of the mists grew a blue shadow. It was land.

Amelia cheered.

Slim yelled and tossed the sandwich he was eating out the window.

And Bill “permitted himself a smile” before bringing the Friendship down just as its motor sputtered out of gas. After a flight of twenty hours and forty minutes, they arrived at Burry Port (near Swansea), Wales, having passed just south of Ireland.

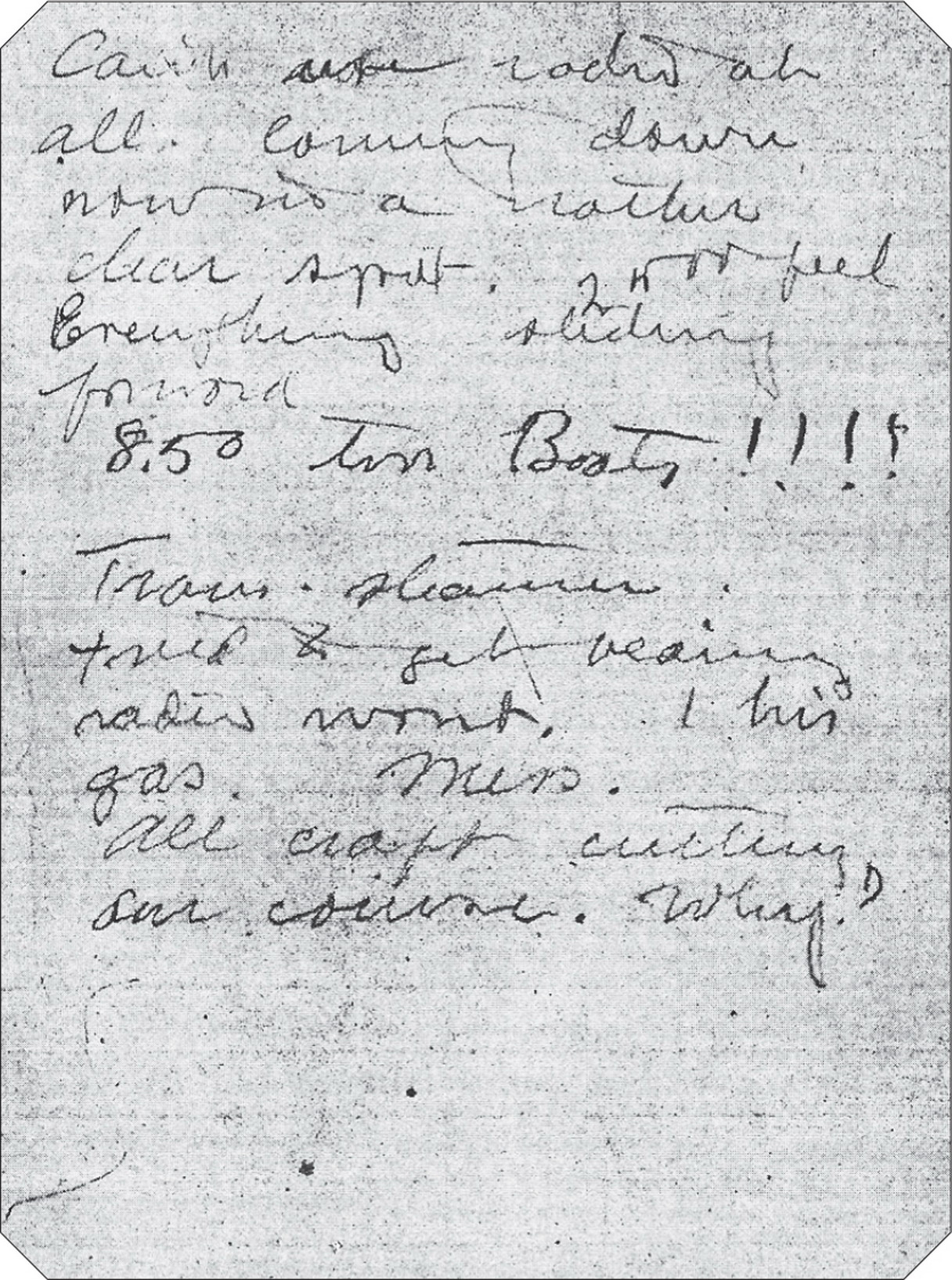

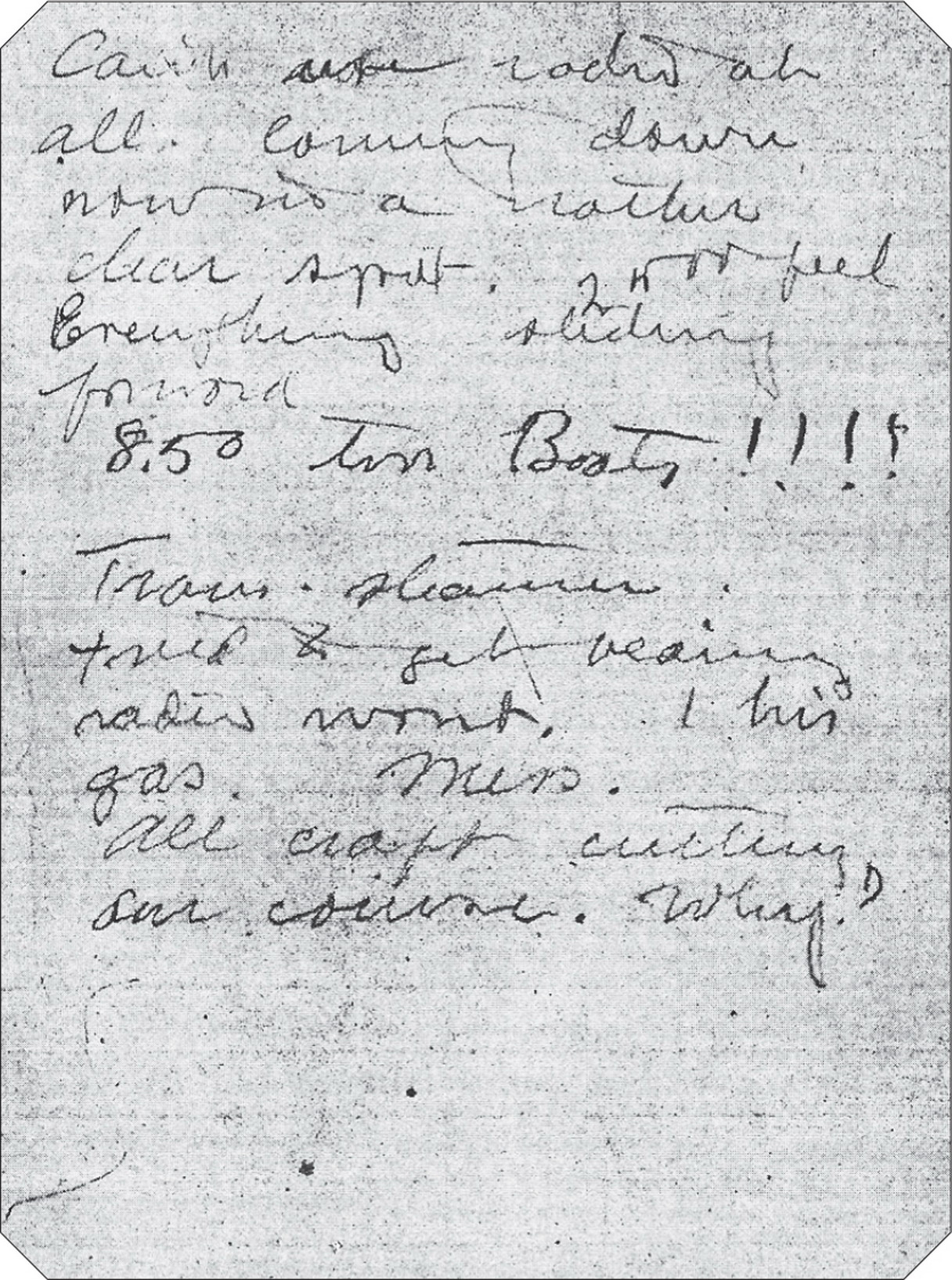

A page from Amelia’s logbook shows her often scrawled handwriting.

This entry reads:

Can’t see land at

all. Coming down

now into a rather

clear spot. 2400 feet

Everything sliding

forward

8.50 ton Boats!!!!

Trans-steamer

tried to get bearing

radio wont. 1 hr

gas. Mins.

All craft cutting

our course. Why?

They tied up to a buoy near some railroad docks. “We were still some distance from shore,” recalled Amelia. “The only people in sight were three men on the . . . beach. To them we waved, and Slim yelled lustily [for a boat].”

The men looked them over, then went back to work. “The Friendship simply wasn’t interesting,” said Amelia. Desperately, she waved a towel out the plane’s front window.

“One friendly soul pulled off his coat and waved back,” she remembered.

A whole hour passed before a boat finally came out, and three hours before the citizens of Burry Port realized that history had just landed in their little village. Word spread, and thousands of people turned out to greet the first woman to fly across the Atlantic. Amelia tried to tell them that the credit belonged to Bill and Slim. But the public only had eyes for her.

From the doorway of the Friendship, Amelia tries to get the attention of the people onshore. (picture credit 10.7)

Overnight, Amelia became a celebrity. The morning after the flight, President Calvin Coolidge sent her a congratulatory telegram; carmaker Henry Ford put a limousine at her disposal. In London (where she traveled the day after the landing), she met Winston Churchill—then chancellor of the British exchequer—and dined with members of royalty.

In late June she sailed for home, arriving in New York City on July 6 to a frenzied welcome. There were parades, receptions, medals awarded in New York, Boston and Chicago. There were interviews and photographs, magazine covers and product endorsements, newsreels and lectures and even a book deal. In August, George Putnam published Amelia’s account of the flight, titled 20 Hrs., 40 min.: Our Flight in the Friendship. Consisting mainly of excerpts from her logbook, it was written during her three-week stay at the Putnams’ Rye, New York, estate. Curiously, she dedicated it to Dorothy Putnam.

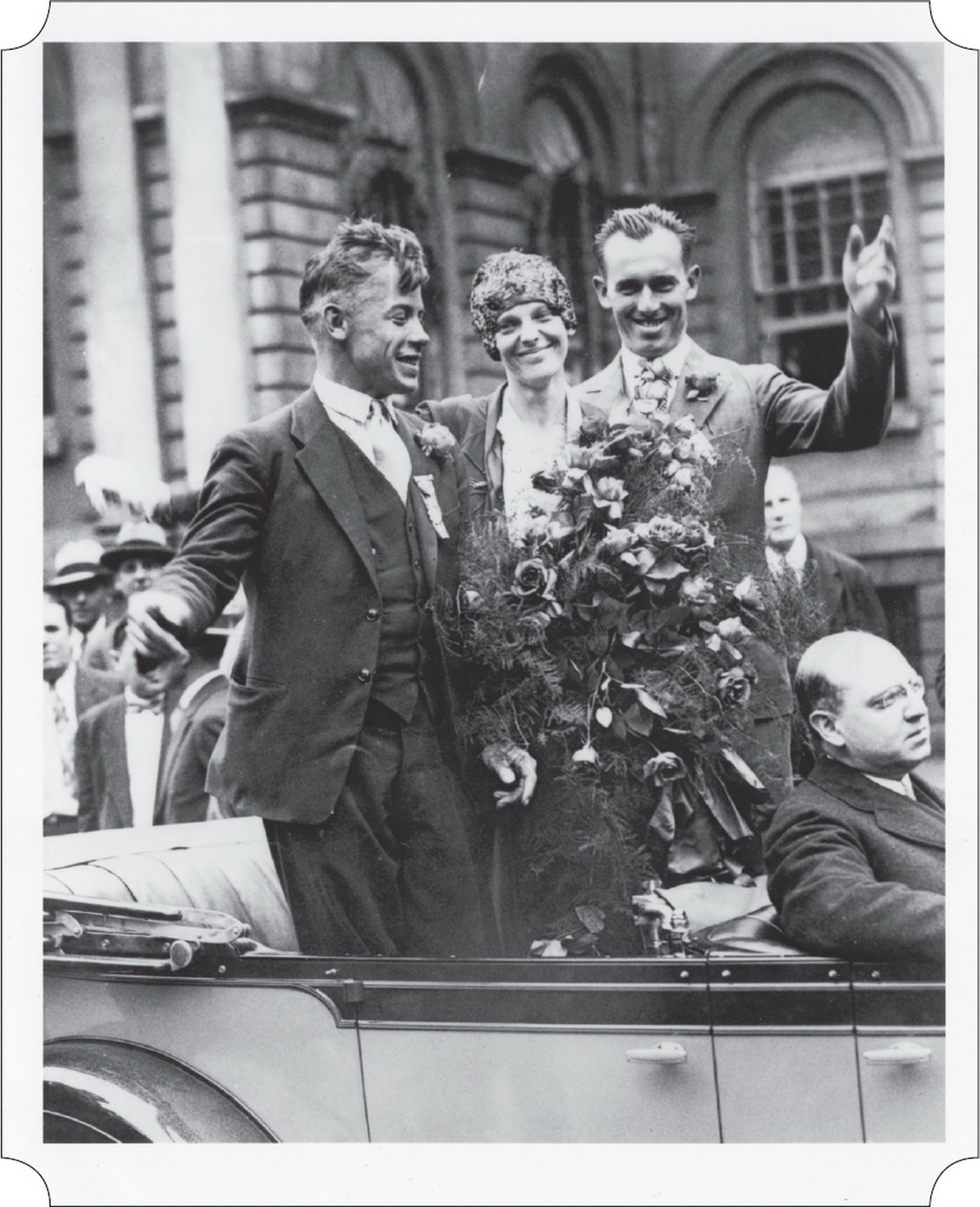

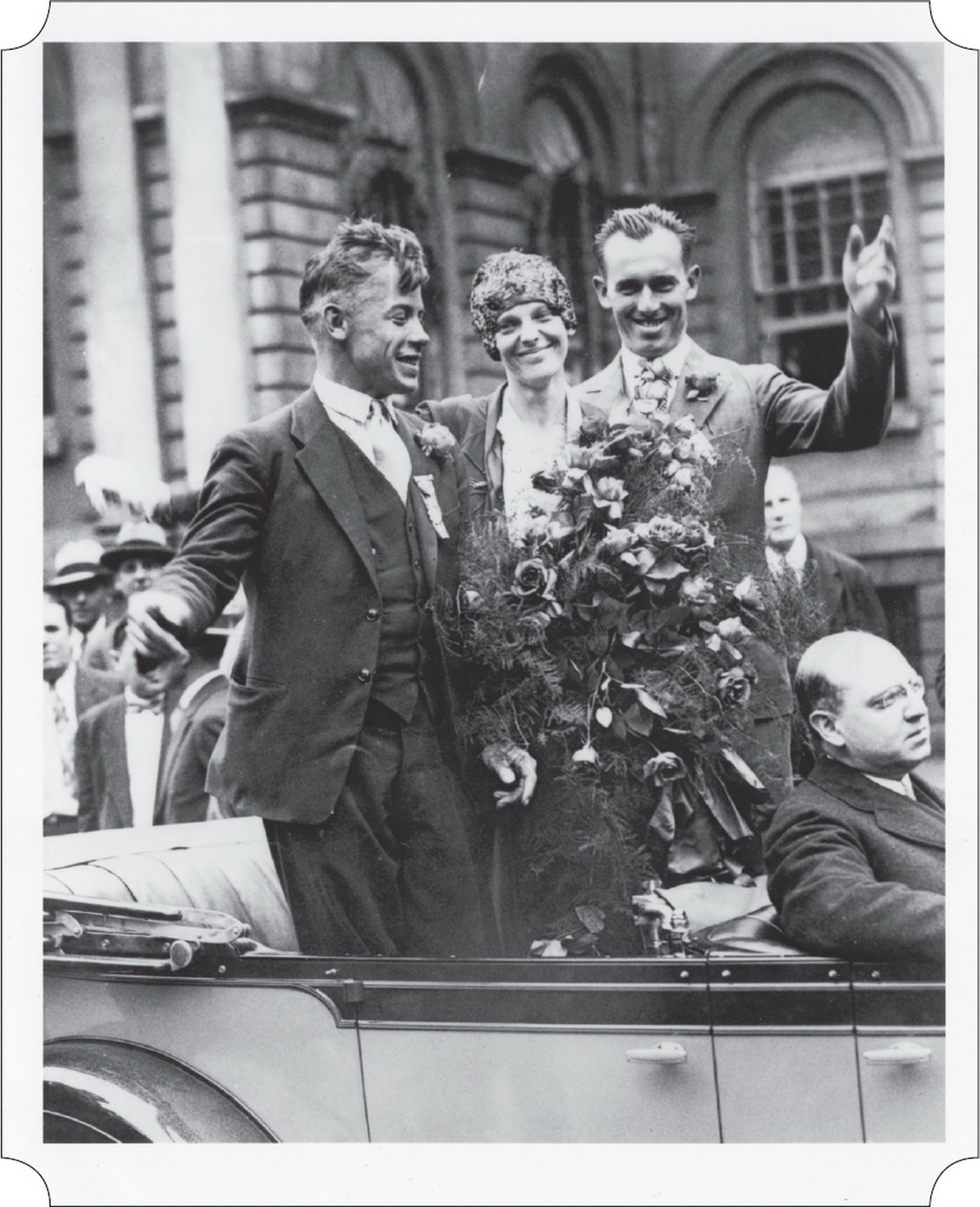

From left to right, Bill Stultz, Amelia and Slim Gordon smile and wave during New York City’s homecoming parade. (picture credit 10.8)

How did Amelia feel about all the hoopla?

“She enjoyed the attention . . . the publicity,” said Muriel. She was also “acutely aware of the fact that her fame would have been short-lived if not for George.” In those days, fliers often made the front pages of the newspapers. But the public’s interest never lasted long—usually only until the next aviator seized the headlines. George Putnam knew that once Amelia’s name dropped out of the newspapers, she would be just another female pilot. So he exploited every opportunity to gain publicity for her. Through his vast connections, she met politicians and celebrities; she christened ships, cut ribbons, opened new buildings, gave speeches and interviews. And wherever she went, whatever she did, a newspaper photographer was always there to record the moment. George made sure of that.

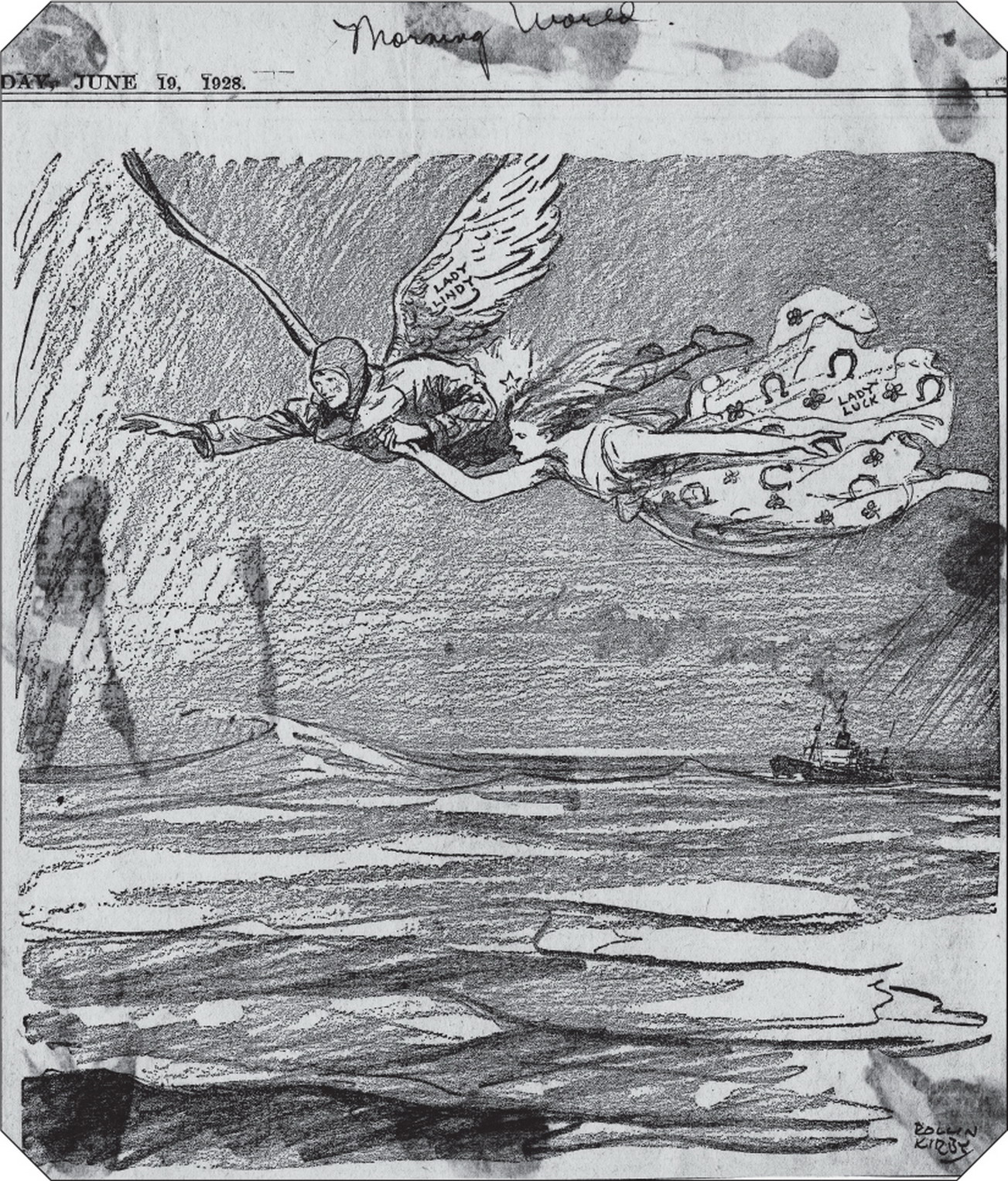

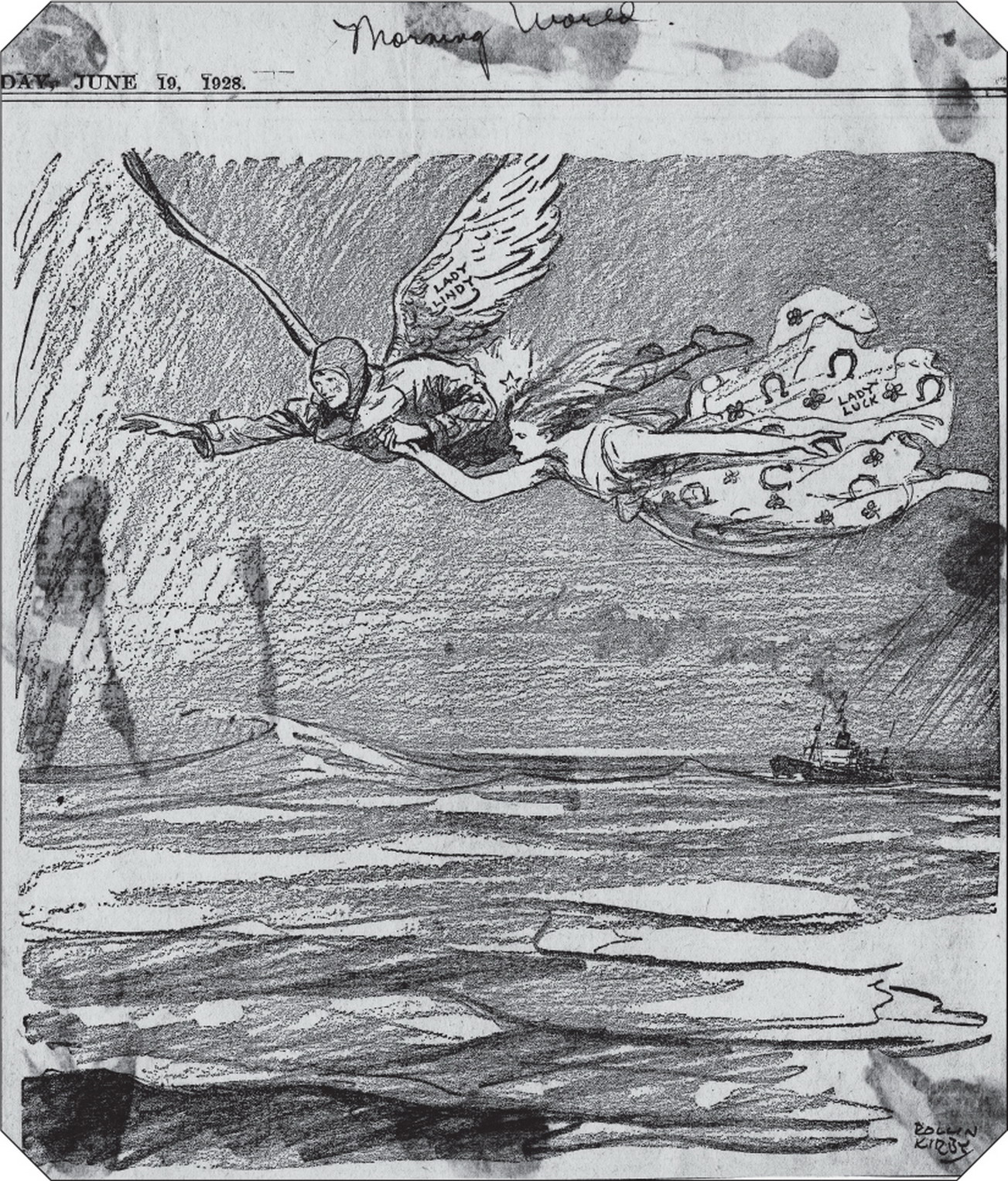

This cartoon, showing Amelia as “Lady Lindy” crossing the Atlantic with “Lady Luck,” appeared in newspapers across the country on June 19,1928. (picture credit 10.9)

Amelia typed away at her book, creating manuscript pages like this one. (picture credit 10.10)

Amelia saw the career George had mapped out for her—famous flier, lecturer, author—and she wanted it. Wrote one historian, “She was completely committed to the commercial property ‘Amelia Earhart,’ and was absolutely driven to make it a recognized name brand.” She knew that if she wanted to fly, she would have to earn money. So she took all of George’s advice to heart. “I was conscious of [his] brilliant mind and keen insight,” she explained. “I recognized his tremendous power of accomplishments and respected his judgment.”

Earhart Enterprises

Between 1928 and 1937, Amelia was constantly in the limelight. This was essential, since flying was very expensive. In order to fly, she needed to raise money; in order to raise money, she needed to maintain her celebrity.

Amelia put it this way: “I make a record [flight] and then I lecture on it. That’s where the money comes from. Until it’s time to make another record.”

George put it another way: “It is sheer, thumping hard work to be a hero.”

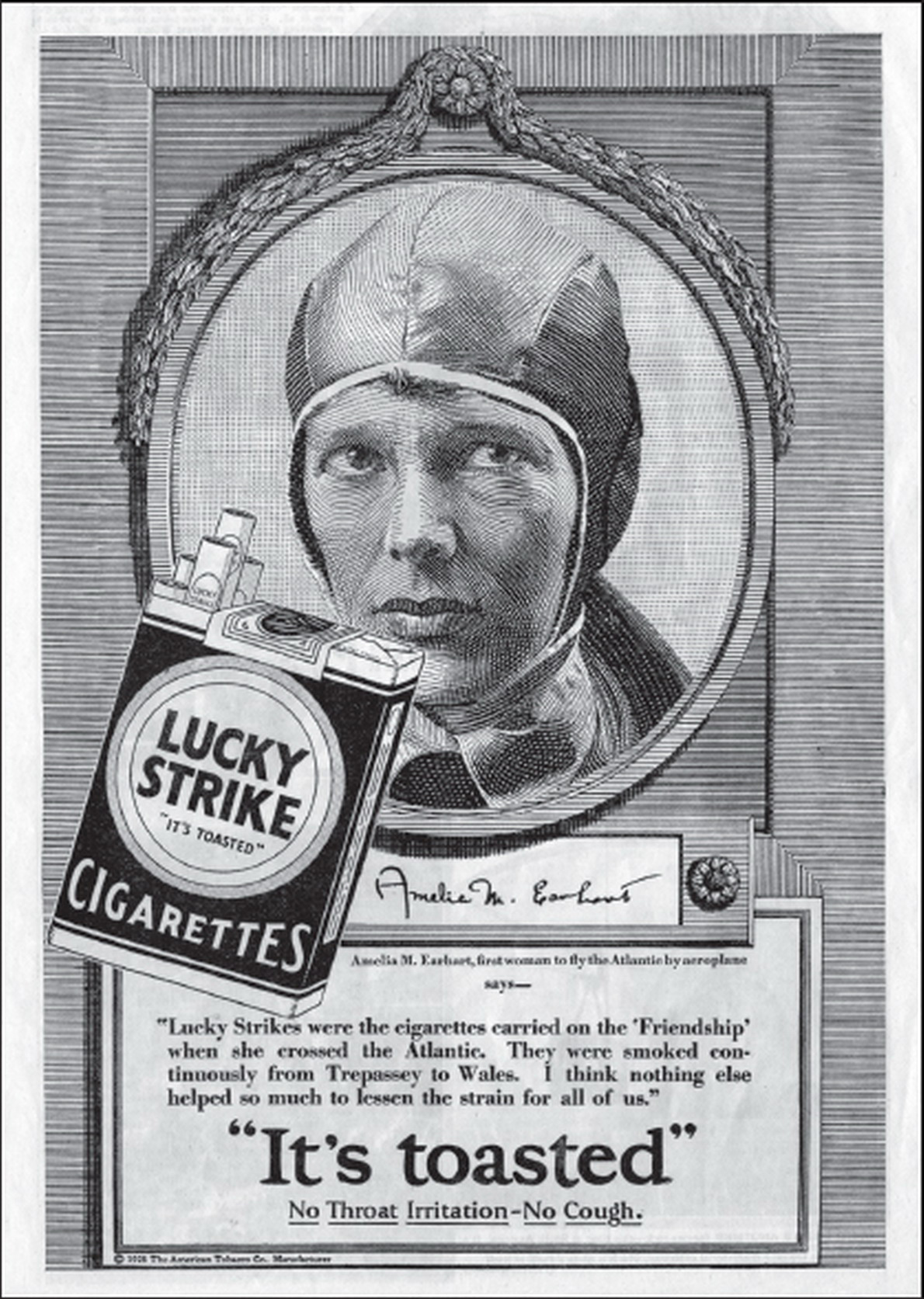

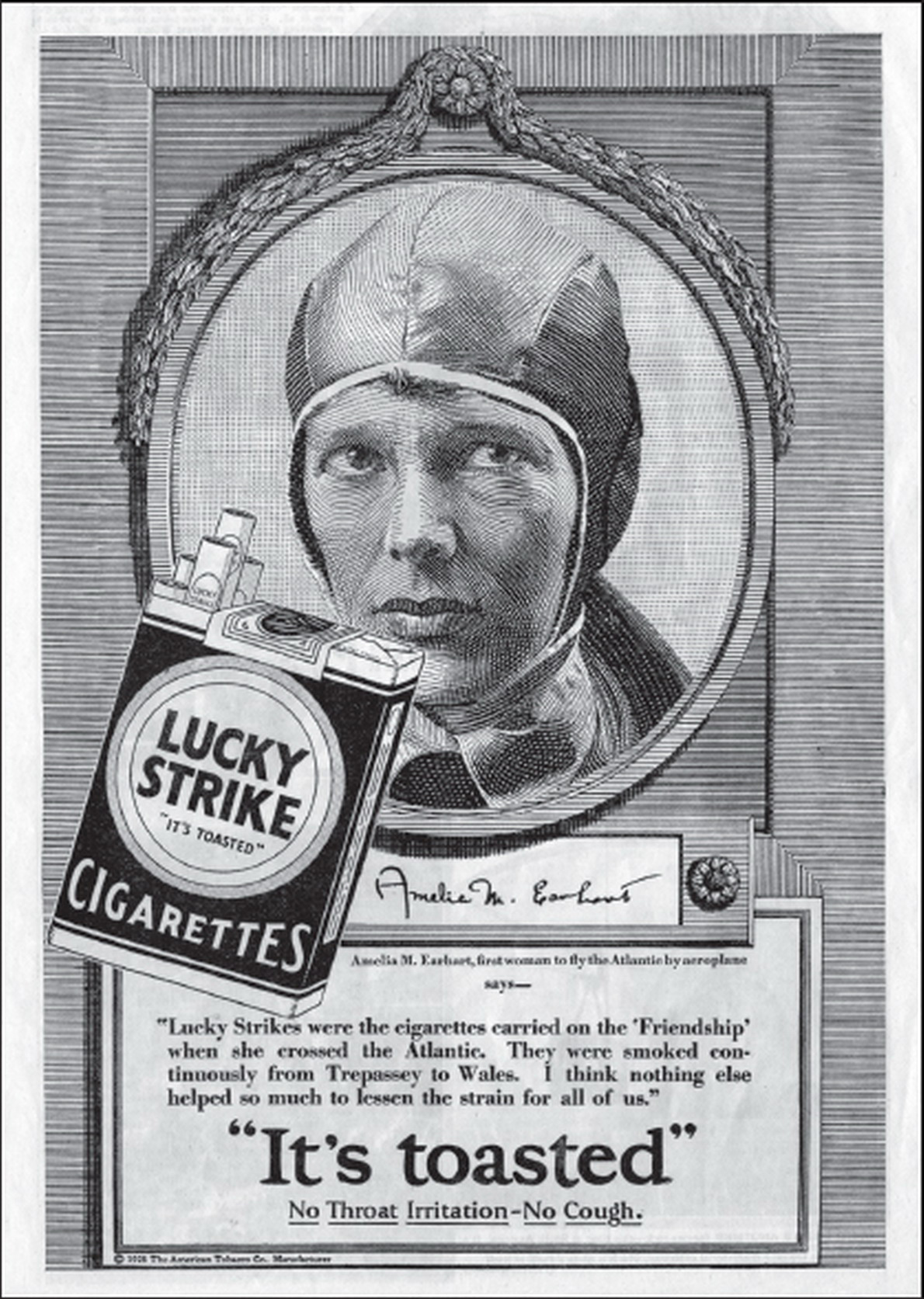

And so Amelia endorsed products such as Kodak film, Stanavo engine oil, Franklin and Hudson automobiles and Lucky Strike cigarettes (even though she didn’t smoke).

She had her photograph taken doing exciting things like parachuting, deep-sea diving and dining with movie stars.

This endorsement for cigarettes earned Amelia $1,500.

A deep-sea diving stunt in Long Island Sound resulted in a contract for a series of magazine articles. (picture credit 10.12)

She even went into business for herself, establishing the Amelia Earhart Clothing Company in 1933. Amelia herself designed the clothes, which sold exclusively in Amelia Earhart Shops in such upscale department stores as Macy’s and Marshall Fields. “I have tried to put the freedom that is in flying into my clothes,” she said in an interview. “Good lines and good materials for women who lead active lives.” Sadly, the fashion industry was too competitive, and Amelia’s business lasted only a year.

An advertisement for clothing “designed by Amelia Earhart.” (picture credit 10.13)

The best way to maintain celebrity and make money was by lecturing. Back in the days before television, the lecture circuit—even more so than radio and newsreels—was the most important way for popular figures to reach the public. Here was a chance for people in Terre Haute, Indiana, and Tacoma, Washington, to actually see and hear their heroes. For one night, at least, they could personally connect with the most famous and influential people of their time.

Amelia became a popular speaker on the lecture circuit. In 1933 alone, she delivered thirty-three talks in twenty-five days. In 1934 she appeared onstage 135 times, before audiences estimated at a total of eighty thousand. Between September 30 and November 3, 1935, she crisscrossed her way from Youngstown, Ohio, to Michigan, on to Minnesota, through Nebraska, into Iowa, to Chicago, then down to central Illinois, into Indiana, back up to Michigan, back to Chicago, off to Missouri and Kansas, and back to Indiana, finally finishing in Wilmette, Illinois. “Life on the lecture tour is a real grind of one-night stands and one hotel after another,” Amelia wrote to her mother. Still, she was earning between $250 and $300 for each lecture (about $3,500 nowadays), a tidy sum back then. Lecturing quickly became her major source of income. “The Earhart name had become a moneymaker,” said one friend.

A flyer promoting one of Amelia’s lectures. (picture credit 10.14)

As for George, he not only adored Amelia but also enjoyed her fame. It stroked his ego to know he had almost single-handedly made her one of the most famous women in the world. “It was fun,” he said. He taught her how to talk into a microphone, avoid lowering her voice at the end of a sentence and smile with her lips closed so people wouldn’t see the gap between her two front teeth.

When George—who was never far from her side—suggested she looked better without a hat, Amelia stopped wearing one. The hatless tousled curls became part of her image.

When George proposed she fly herself from speaking engagement to speaking engagement because “it was so much more thrilling to the public,” Amelia did.

And when George advised her to make a donation to Commander Byrd’s Antarctic expedition because it would add to her “charitable image,” Amelia promptly wrote a check for $1,500. George made sure that news of her “selfless generosity” was published on the front page of the New York Times.

As one of their friends said, “It was [George] who provided the design for those adventures of hers, and pulled them off. I wonder if the slim, frail girl-in-slacks would have startled the world without the explosive, pragmatic apostle of the impossible to goad her on. . . . Both realized they had a good thing going and I suspect Amelia needed George more than he needed her.”

After finishing her book, however, Amelia was also eager for something else. “All I wished to do in the world,” she said, “was to be a vagabond—in the air.”

Amelia’s Little Plane

While in England after the transatlantic crossing, Amelia had test-flown a small sports plane known as the Avro Avian. She loved it. The Avian was fast and easy to handle, and so light that she could move it simply by picking up its tail and pulling. Its wings could even be folded up for easy storage. Anticipating some income from the success of the Atlantic flight, she bought the little plane and had it shipped to the United States. When it arrived in Boston weeks later, George laughed. “It’s a bit of a pocket plane,” he joked.