WHILE AMELIA DREAMED OF AN AROUND-THE-WORLD FLIGHT IN A BIGGER PLANE, an unusual opportunity presented itself.

“We want you at Purdue University,” the school’s president, Edward C. Elliott, told her in the spring of 1935.

“What would I do?” asked Amelia. Without any teaching qualifications, she wondered how she could contribute.

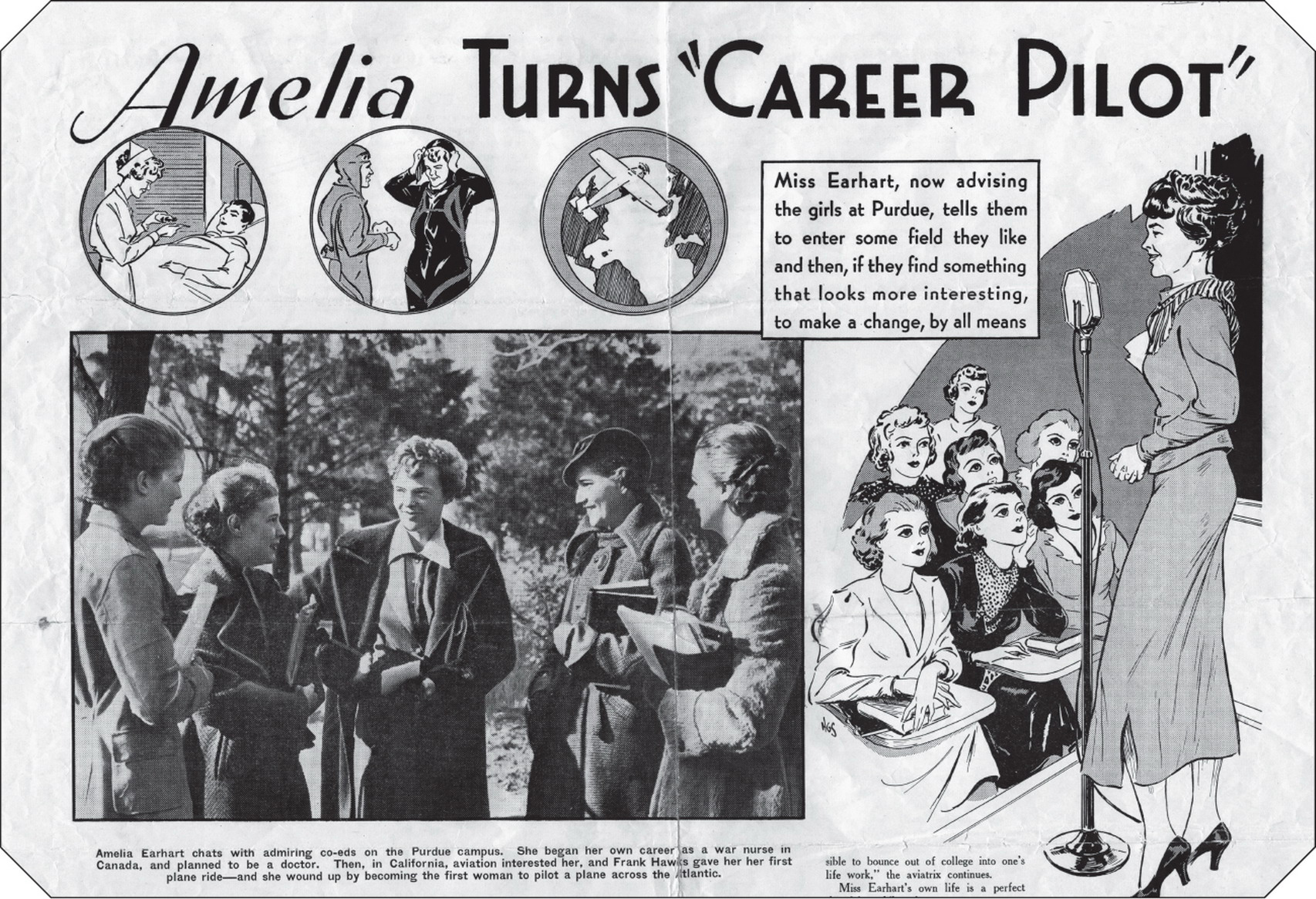

But Elliott knew. He wanted the flier to inspire Purdue’s female students to take up careers in such male-dominated fields as agriculture and engineering.

The idea appealed to Amelia. Women, she believed, should be encouraged to take chances. They should look beyond the comfort and security of marriage and instead “dare to live.” She once told an audience, “There are a great many boys who would be better off making pies, and a great many girls who would be better off as mechanics.” Now she eagerly agreed to spend part of the 1935–1936 school year on Purdue’s campus.

Amelia chose to live in the women’s residence hall, where she delighted her dorm mates with her independent behavior. She put her elbows on the table during meals and once showed up for dinner in flying clothes rather than the required skirt. This behavior caused ripples. When the students tried following Amelia’s example, the housemother scolded, “As soon as you fly the Atlantic, you may!”

But Amelia’s influence with the female students went far deeper than table manners. After dinner the girls often followed her into the housemother’s den, where they nibbled cookies and talked late into the night. Sitting cross-legged on the floor, Amelia led the discussions. “[They] centered around Miss Earhart’s belief that women . . . really did have choices about what we could do with our lives,” recalled one student. “ ‘Study whatever you want,’ she counseled us girls. ‘Don’t let the world push you around.’ ”

Amelia was such a popular teacher that the school’s enrollment of female students increased by fifty percent. Everyone, it seemed, wanted to take one of her classes.

EveryWeek magazine ran this article on Amelia’s new job at Purdue. (picture credit 14.1)

That same fall, Amelia told a reporter that she couldn’t break any more flying records because her Vega was too old. “I’m looking for a tree on which new and better airplanes grow, and I’m looking for a shiny new one to shake down.”

George knew just the tree to shake—Purdue University. Sitting down with President Elliott, he suggested the idea of a “Flying Laboratory,” in which Amelia could study the effects of air travel. It would be, persisted George, “an aeronautical first.”

This idea bubbled in President Elliott’s mind until a dinner party at his home a few weeks later. There Amelia talked about her dreams for women and aviation, and how she would like her next flight to be “a thorough check of modern equipment. I expect to keep a log of what happened to personnel and machine under various conditions. Records such as these . . . can do much to safeguard subsequent flights,” she said.

One of the other dinner guests, David Ross, was so impressed by Amelia’s words that he offered to donate $50,000 toward buying her a plane. Over the next few months, further donations totaling an additional $30,000 in money and equipment came from J. K. Lilly (of the Eli Lilly drug company), Vincent Bendix (a car and airplane inventor and an industrialist) and the manufacturing companies Western Electric, Goodrich and Goodyear.

The next spring, Elliott announced the creation of the Amelia Earhart Fund for Aeronautical Research for the purpose of “develop[ing] scientific and engineering data of vital importance to the aviation industry.” The fund’s first purchase would be an $80,000 (one million dollars nowadays) twin-engine customized Lockheed Electra, so that Amelia Earhart could pursue the long-distance flights she dreamed of. The plane’s title would be in her name, and decisions about how the plane would be used would be hers alone.

Amelia took possession of her new plane on her thirty-ninth birthday, July 24, 1936. The Electra was breathtaking. “I could write poetry about that ship,” she gushed after she flew it for the first time.

Science or a Racket?

Amelia’s announcement of her “Flying Laboratory” and her proposed around-the-world flight was met with sharp criticism. In his widely circulated newspaper column, aviation writer Alford Williams—a highly respected flier and a leader in aircraft development—scoffed at the aviator and her motives. He wrote:

Like every other human enterprise, aviation suffers from a great number of ingeniously contrived rackets. Daring courageous individuals with nothing to lose and all to gain have used and are using aviation merely as a means toward quick fortune and fame. The worst racket of all is that of individually sponsored trans-oceanic flying . . . [where] the personal profit angle in dollars and cents, and the struggle for personal fame, have been camouflaged and presented under a banner of “scientific progress.”

. . . Amelia Earhart’s “Flying Laboratory” is the latest and most distressing racket that has been given to a trusting and enthusiastic public. There’s nothing in that “Flying Laboratory” beyond duplicates of the controls and apparatus found on board every major airline transport, and no one ever sat at the controls of her “Flying Laboratory” who knew about the technical side of aviation. . . . Nothing is said about the thousands of dollars she and her manager-husband expect to [earn]. Nothing at all was hinted of the fat lecture contracts, the magazine and book rights for stories of the flight. . . . No, the whole affair was labeled “purely scientific” for public consumption. . . . It’s high time that the Bureau of Air Commerce puts an end to aviations biggest racket—“Purely Scientific” ballyhoo.

Now Amelia began giving serious thought to her new adventure—circling the globe at the earth’s middle. That was the longest way to do it—27,000 miles. More important, it was the most novel way to do it.

Amelia knew that the winds of aviation were changing. The public was tiring of record-breaking flights. Almost every major record had been broken, and all the major flight routes (across oceans and countries) had been spanned. In fact, by 1936 commercial airlines had made it possible for anyone to fly as a passenger across the Pacific.

What was so special about long-distance stunt flying now? Not much. According to historian Susan Ware, “The only thing left was to find new routes or to do old ones faster or with a twist or gimmick.”

Flying around the world, however, was hardly unique. Between 1924 and 1933, six different expeditions had circled the globe, including one solo flight made by the famous pilot Wiley Post. Amelia’s only novelty was taking the long equatorial route around the world. That and being a woman. (It should be noted that although Amelia initially planned to circle the globe all by herself, she soon saw problems with this plan and decided to take along a navigator who could help find the way across long stretches of jungle and ocean.)

When George asked why she wanted to attempt such a trip, she replied, “It is my frosting on the cake.”

“Life is full of other challenges,” he insisted.

Amelia smiled. “Please don’t be concerned,” she said. “It just seems that I must try this flight. I’ve weighed it all carefully. With it behind me life will be fuller and richer. I can be content. Afterward it will be fun to grow old.”

George knew his independent wife’s mind was made up. He vowed “to do everything in my power to help.”

Flying the Friendly Skies

Pilots like Amelia Earhart and Charles Lindbergh weren’t the only ones taking to the air in the 1920s and 1930s. Regular Americans were, too. But they weren’t handling the controls themselves. They were flying as passengers.

It was the United States Post Office that gave passenger airlines the boost they needed. The post office began using airplanes to deliver the mail in 1920. By 1925, these planes were delivering 14 million packages and letters a year. And in that time, the post office had maintained regular flight schedules, created airports across the country, and established air routes. That was when the government decided to transfer airmail service to private companies. The government believed that private companies could transport the mail more efficiently. In return, private companies would pay the government for use of those established air routes.

Private companies eagerly bid for the air routes. And the winners became transportation giants. There was Pan American Airways, which was awarded the New York-to-Boston route; American Airlines, which received the St. Louis-to-Chicago route; and Transcontinental and Western Air (TWA), which won the Salt Lake City-to-Los Angeles route. These companies now began pouring money into passenger travel technology, and by 1928, Boeing had introduced a plane that could carry seventeen passengers.

An early passenger plane, circa 1928. (picture credit 14.2)

But air travel at this time was primitive. Airplanes could not fly over mountains. They could not fly safely at night, and they had to land frequently to refuel. As for the flights themselves, they were uncomfortable, loud and bumpy. Since planes were nothing more than fabric-covered wooden frames, passengers had to stuff cotton in their ears to shut out the noise of the engines. And without a proper air circulation system, cabins reeked of motor oil, gasoline and the disinfectant used to clean up after airsick passengers. The only way to escape the smell was to open a window, which turned a plane’s cabin into a wind tunnel. Despite all these inconveniences, however, plane travel grew from around 6,000 passengers in 1926 to 173,000 passengers in 1929.

Around 1930, airline companies began hiring “air stewardesses” in hopes of making their passengers more comfortable. These women (forerunners of our modern-day flight attendants) not only offered passengers water, a sandwich and gum to help relieve ear pain (cabins were not pressurized back then), but they also carried luggage, took tickets and tidied up the cabin after a flight. More important, they were all registered nurses, capable of providing medical care in emergencies. Remarked one passenger, “They make things so much more homey.”

Still, air travel in the 1930s was limited to the wealthy and people who had an important reason to fly. After all, flying was four times as expensive as taking the train, and the only reason most people chose it was speed.

All that changed in 1936, when the DC-3 was introduced. It could fly coast-to-coast faster than any passenger plane before, and it offered comfort. The plane was fitted with upholstered chairs that swiveled toward or away from the windows. The cabin was soundproofed (no more wind and engine noises) and ventilated (no more bad smells).

The interior of the DC-3, 1936. (picture credit 14.3)

The introduction of the DC-3 is credited with increasing the number of airline passengers from around 474,000 in 1932 to 1,176,858 in 1939. And even though it would be several years before more people traveled by air than by train, Americans were growing comfortable with the idea of flight. As one TWA ad liked to remind the public, “Now we can all soar like Amelia.”

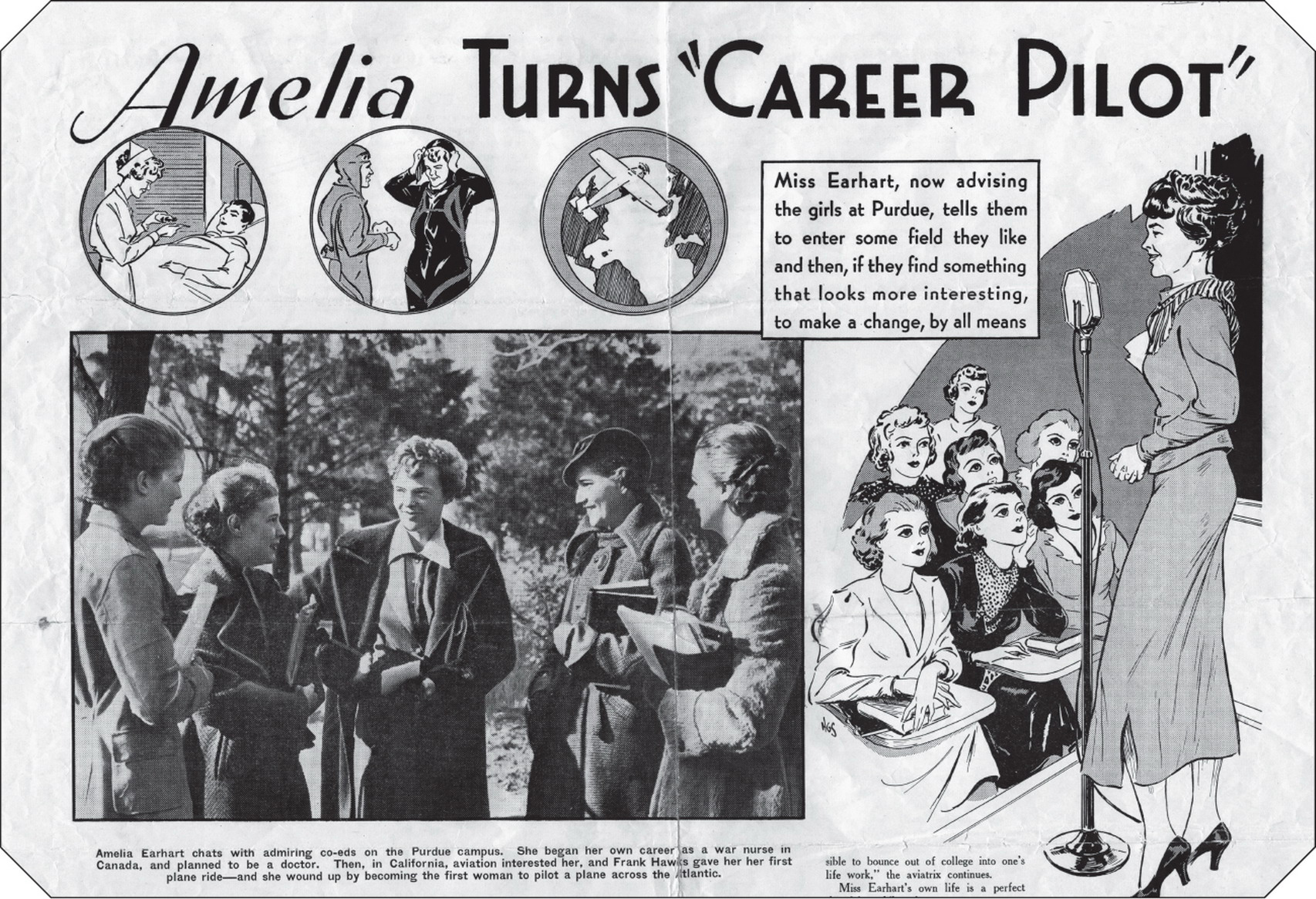

This publicity photo shows George and Amelia studying a globe, as well as charts, in preparation for the world flight. (picture credit 14.4)

A flight around the world required lots of preparation. A course had to be marked out. Maps had to be drawn. Weather reports had to be studied. And what type of equipment would Amelia need to take along? The Putnams’ living room, recalled one friend, “was just completely covered . . . with things they were testing—compasses, parachutes, three different kinds of rubber rafts.”

Starting in early 1936 (months before Amelia took possession of the Electra), George flung himself into the enormous task of obtaining permission for her to fly over or land in every country along her route. Additionally, he had to arrange for supplies of gasoline and oil at more than thirty points. Then he had to decide at which of these stops the plane would need to be overhauled. After all, the plane couldn’t fly 27,000 miles without lots of maintenance. Once he decided where the plane would be worked on, he had to send the necessary engine parts and mechanics to those places.

“I felt like a master magician and jigsaw puzzle juggler,” said George.

The Putnams invested their entire life’s savings in the around-the-world flight. “I more or less mortgaged my future,” Amelia admitted.

George agreed. “It is a gamble,” he said. If his wife failed, they would be broke. But “if she succeeds, our financial futures are set.”

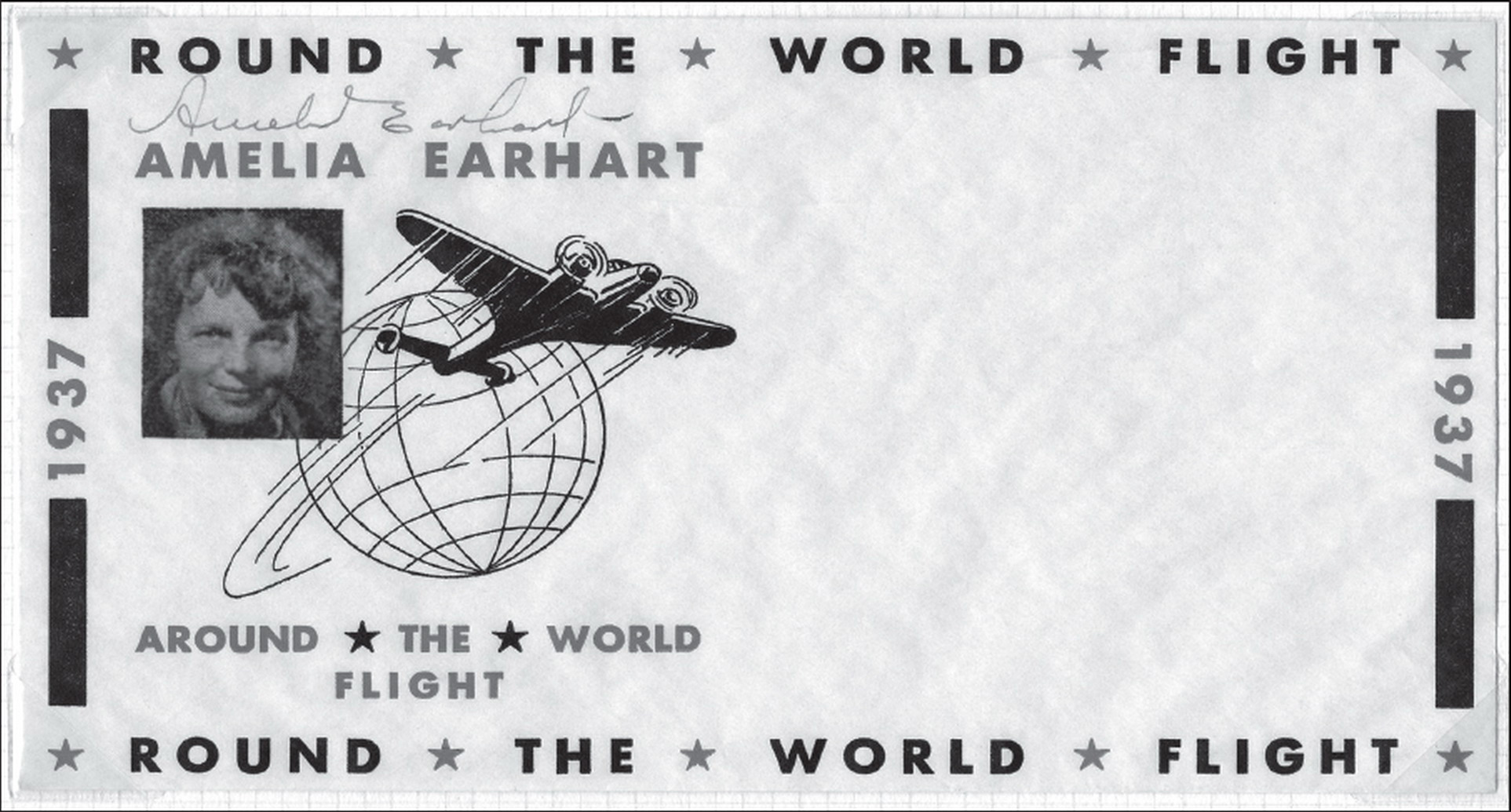

Already, George had cut a deal with the New York Herald-Tribune for a syndicated column to be written by Amelia during the trip. He had lined up a lucrative lecture tour to start as soon as she returned. He’d even negotiated a book contract with Harcourt Brace. But his most interesting moneymaking scheme involved stamp covers.

In partnership with Gimbel’s department store, George had 5,000 stamp covers (envelopes with commemorative markings) printed. These stamp covers were then offered to collectors for $5 apiece. They sold like hotcakes. Why? Because Amelia not only signed each cover, but she also promised to take them along on the flight.

A stamp cover Amelia signed (and left behind) before her flight around the world. (picture credit 14.5)

Signing these stamp covers became a sort of game: ten autographs before her morning orange juice, fifteen before her bacon and eggs, twenty-five before bed. She was willing to do anything for this flight, and the sale of the stamp covers would defray a significant portion of the cost. (The Putnams stood to make $25,000 from the covers, about $250,000 nowadays.)

Perhaps this explains why Amelia chose to keep the 5,000 stamp covers in the Electra’s nose cargo hold, even as she obsessed about carrying unnecessary weight. To lighten the plane, she would remove clothes, parachutes and even her Morse code key. But she never abandoned the stamp covers. When she disappeared, they went with her.

Meanwhile, Amelia wrestled with the biggest logistical problem of her flight—the Pacific Ocean. She could not fly over its entire expanse nonstop. Somehow she needed to refuel. How? She had an idea, but it required some help from her friends the Roosevelts. In November 1936 she wrote:

Dear Mr. President,

Some time ago I told you and Mrs. Roosevelt a little about my confidential plans for a world flight. . . . The chief problem is the jump westward from Honolulu. The distance thence . . . is 3900 miles. . . . With that in view, I am discussing with the Navy a possible refueling in the air over Midway Island. . . . Knowing your own enthusiasm for voyaging, and your affectionate interest in Navy matters, I am asking you to help me secure Navy cooperation—that is, if you think well of the project. If any information is wanted as to purpose, plans, equipment etc., Mr. Putnam can meet anyone you designate, any time, anywhere.

After reading the letter, President Roosevelt agreed to “do what we can.”

Amelia, however, changed her mind. Rather than refueling in the air, she switched to the possibility of landing on Howland Island, a tiny island within flying range of both New Guinea and Hawaii. The problem was, Howland Island didn’t have an airstrip.

Could the United States government build her one? Amelia asked President Roosevelt. PLEASE FORGIVE TROUBLESOME FEMALE FLYER FOR WHOM THIS HOWLAND ISLAND PROJECT IS KEY TO WORLD FLIGHT ATTEMPT, ran one of her telegrams to the White House.

Roosevelt came to her rescue. He authorized funds for the construction of an airstrip on Howland Island, then made sure it was built swiftly and secretly. After all, commented one Earhart biographer, “the American taxpayer—in the throes of the Great Depression—might not have understood the necessity of building an entire airport for one-time use by a private individual.”

Pranks!

As the starting date for the world flight neared, tensions grew. Believing that his wife needed a good laugh, George decided to play a prank. One evening, while he and Amelia were dining with navigator Harry Manning, as well as mechanic Bo McKneely, George slipped away from the table and made a secret telephone call to the chief of police.

Later, as Amelia drove the others to the airport, she was pulled over for speeding.

She argued with the policeman. There weren’t any speed-limit signs posted, she complained, and she needed to get to the airport. She had a plane to work on.

But the policeman refused to listen to her arguments. He dragged her—along with the others—to night court, where the judge gave Amelia a stern lecture on driving too fast. Then he turned to George. “Are you responsible for this woman?”

Straight-faced, George replied, “No, Your Honor. I’m just a relative and I disown her.”

People in the courtroom laughed, and Amelia realized George had played a joke on her.

The judge (who George thought was in on the prank but who really wasn’t) fined Amelia one dollar. As she swept off to the cashier to pay, the judge beckoned George to the bench. Was that lady really Amelia Earhart? he asked.

George assured him that she was.

“I thought you were trying to kid me all the time,” replied the judge. He ordered the fine returned to Amelia.

George laughed and laughed.

But Amelia soon got her revenge. Although George regularly took airplanes, he still suffered from airsickness. “Flying makes me queasy,” he once confessed to reporters. A week after his prank, George boarded a plane for New York. About an hour into the flight, the attendant brought him a brightly wrapped package from Amelia. Eagerly, George tore off the paper to find . . . a raw pork chop.

Amelia had decided to fly from east to west: from Oakland, California, to Hawaii to Howland Island to Australia to Arabia to Africa to Brazil, and then to Miami and home. She figured the trip would take about six weeks.

She had also carefully chosen a navigator. He was Harry Manning, an experienced sailor and licensed pilot, who took a three-month leave of absence from his duties as a sea captain to make the trip.

From Oakland, California, to Howland Island, a third man would also fly with them—Fred Noonan. Noonan, a licensed pilot who had worked as a navigator for Pan American Airways, was put aboard when it was discovered that Manning would need help with celestial navigation (determining location based on the stars and other celestial bodies).

“It appears,” said Amelia in early 1937, “that I am ready.”

Technical advisor Paul Mantz disagreed. He had spent hours training Amelia to fly her new plane. She was a quick study, but Mantz still worried. She was about to make the most dangerous flight of her life in a powerful, complicated airplane loaded with special equipment—various weight, altitude and engine monitors. None of Amelia’s previous planes had been equipped with any of these instruments. “You need more practice,” Mantz advised her.

She needed more practice with her radio equipment, too. Joseph Gurr, who had been hired to install the plane’s communication system, was eager for Amelia to learn how to use her radio and direction-finding equipment. He wanted to show her how to tune the receivers and how to operate the transmitters; to teach her correct radio procedures and help her understand what her radio system could and could not do. But every time Gurr begged her to come for a lesson, she put him off. She was too busy, she said. Her schedule was full. Finally—just weeks before her departure—she turned up at the airport hangar. Relieved, Gurr assumed he had all day to teach her everything about her radio. But after only an hour, Amelia left for an appointment. Gurr was stunned. “We never covered actual operations such as taking a bearing with the direction finder, [or] even contacting another radio station,” he recalled. This very brief lesson was Amelia’s only formal instruction in the use of her communication system. And it would be her gravest mistake. Wrote one aviation expert, “The solution to Amelia’s future communication problems was right at her fingertips—if only she had understood how her radio worked.”

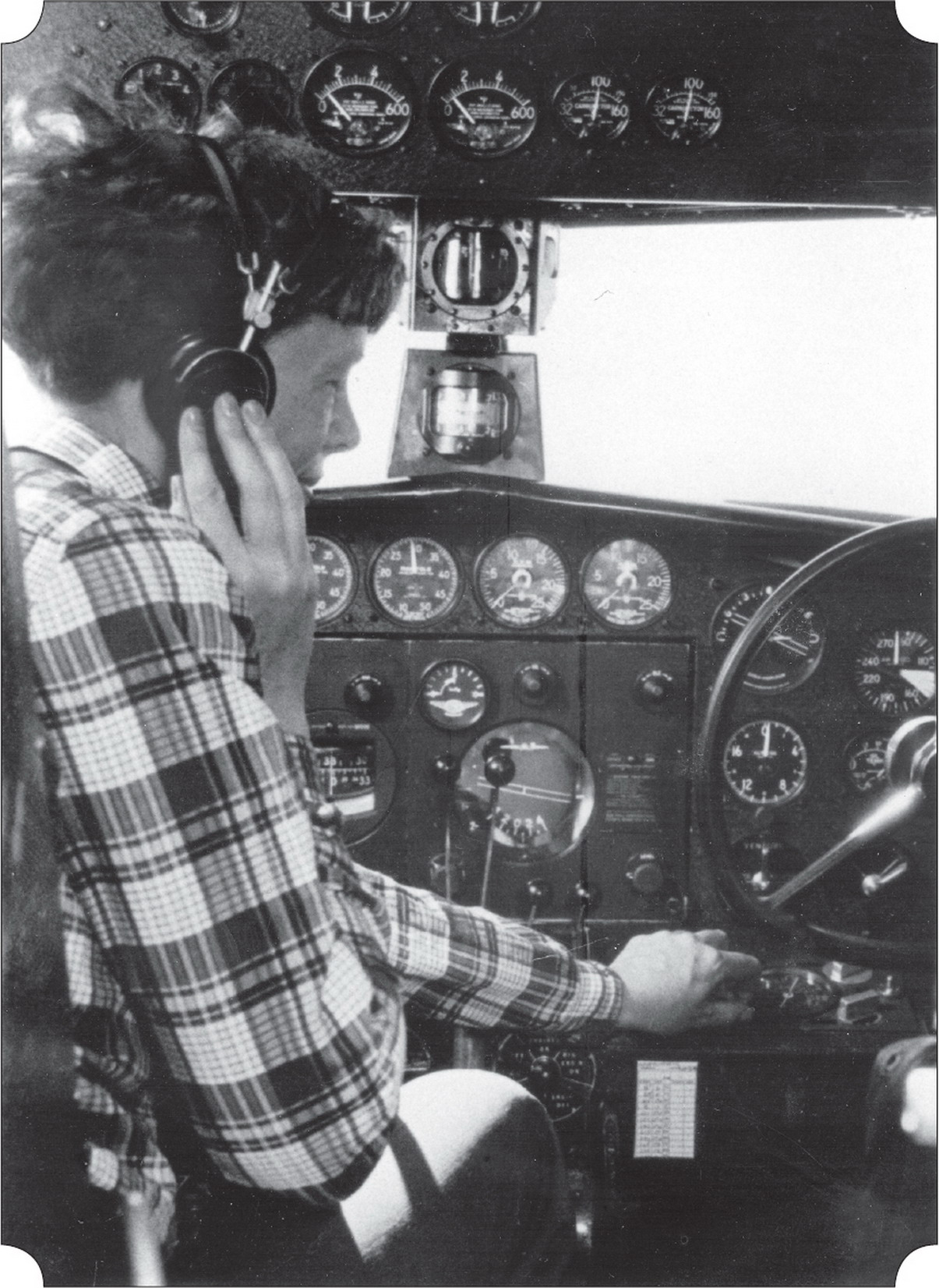

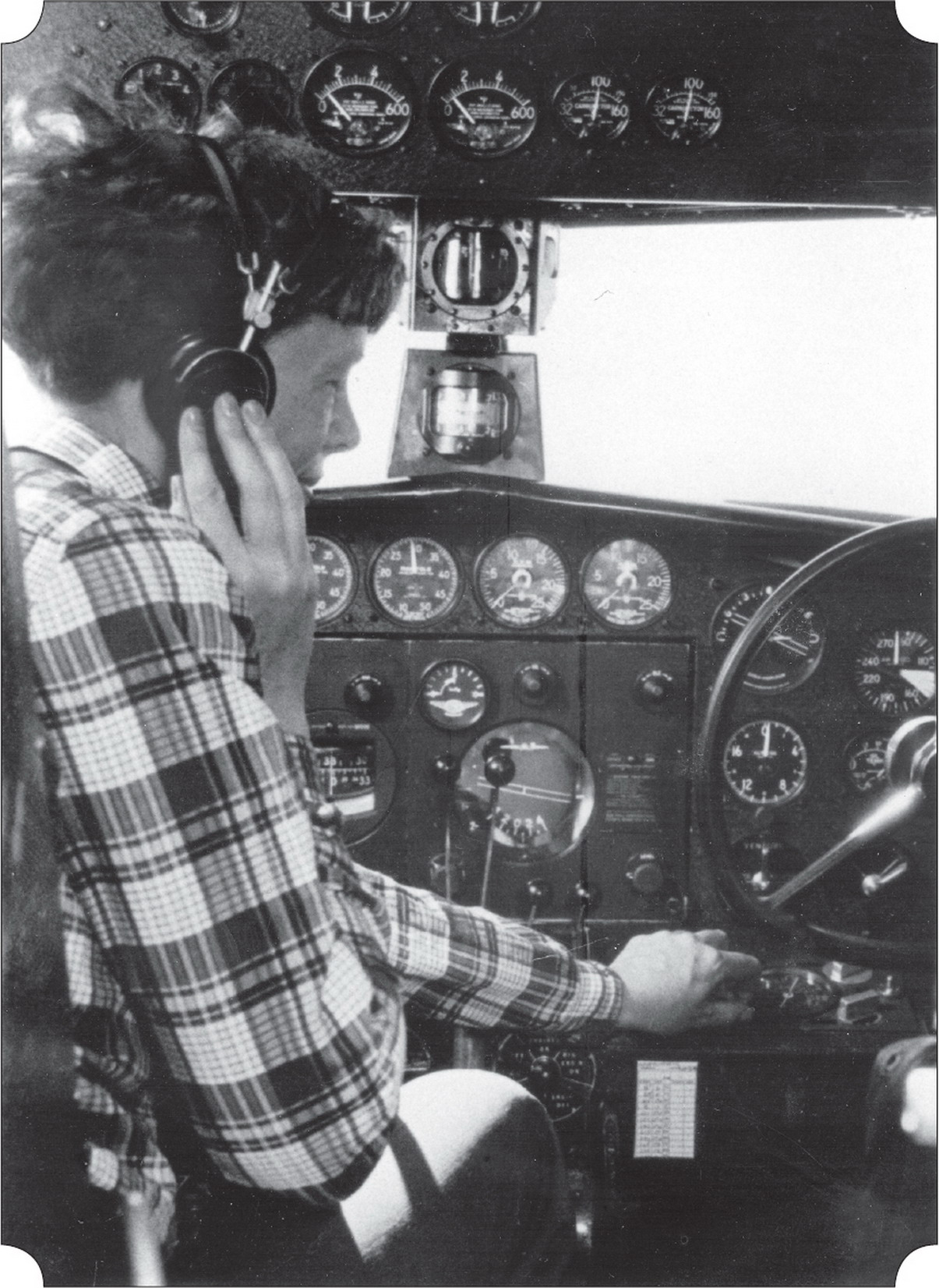

Amelia in the cockpit of the Electra. It measured 4′6″ long by 4′6″ wide by 4′8″ high—a very cramped space for long flights. (picture credit 14.6)

Despite all these concerns, on the afternoon of March 17, 1937, Amelia—along with Harry Manning, Fred Noonan and Paul Mantz—climbed into the Electra. Once the hatch was down, Mantz took over the throttles in the left-hand seat while Amelia handled the flight controls in the copilot’s seat. Even though she had flown the Electra more than two dozen times, Mantz wanted to go over the flying process one last time. Wrote Amelia, “[We] carefully worked out the piloting technique of that start. It was a team-play takeoff.”

As for Mantz (who planned to travel with Amelia only as far as Hawaii), he had plenty of last-minute advice. “Never jockey the throttle,” he told her. “Use the rudder and don’t raise the tail too quick.”

Minutes later, the Electra roared down the field and rose slowly into the sky. “An excellent takeoff on a muddy runway,” an official from the Bureau of Air Commerce later reported to the White House. He didn’t know that the takeoff was really Mantz’s.

Sixteen hours later, the Electra landed in Hawaii. “Smooth flying,” Amelia recorded in her log book, “but the next leg will not be so easy.”

The long Pacific hop to tiny Howland Island was next. This was, by far, the hardest part of the trip. Still, Amelia felt confident. Even though the coast guard cutter Itasca would be standing by at Howland Island to offer help, she didn’t expect to need any. She figured that at the start of the trip, “when everyone was fresh,” and with three fliers aboard (herself, Manning and Noonan), they wouldn’t have any problems finding that tiny dot of land.

Amelia was eager to put this part of the journey behind her, but for some reason she delayed her departure for a day. This delay, the press was told, was due to bad weather. But navy reports later stated that the forecast was for “favorable flying conditions over the entire route.” The real reason, according to Paul Mantz, was that Amelia was exhausted. She needed to rest before setting out on this most difficult leg of her trip.

At daybreak on March 20, Amelia took the throttle herself and prepared to take off. But as the Electra rolled down the runway, the unexpected happened. The plane’s right wing appeared to drop. Amelia corrected by reducing power on the opposite engine, but the plane swung out of control. With a loud crack, the landing gear collapsed, and the Electra “slid on its belly amid a shower of sparks” before coming to a stop.

Quickly, Amelia shut down the engines, preventing a fire. Then she sat for a few stunned moments in the cockpit before crawling out the cabin door behind Manning and Noonan. “Something must have gone wrong,” she said in a dazed voice.

It was a disastrous accident. The Electra’s right wing, both engine housings, the main landing gear, the underside of the fuselage and both propellers were badly damaged. In Oakland, where George awaited word of his wife’s takeoff, the phone rang. It was a reporter for one of the press associations. “Have you heard?” asked the reporter. “They crashed . . . the ship’s in flames.”

Recalled George, “I could not listen further.” Handing the phone to a friend, “I moved out into the cold morning, trying to walk steadily. In a few minutes [people] came racing after me. ‘No fire . . . no fire at all. . . . False report! No one hurt!’ ”

Immediately, George “shakily scribbled” a cable to his wife: SO LONG AS YOU AND THE BOYS OK THE REST DOESN’T MATTER AFTER ALL IT’S JUST ONE OF THOSE THINGS WHETHER YOU WANT TO CALL IT A DAY OR KEEP GOING LATER IS EQUALLY JAKE WITH ME.

An hour later, Amelia telephoned him. “Her voice weary with sadness,” recalled George, “she said she wanted to try again.”

Amelia and George returned home to California, where they decided to postpone the flight until May. The postponement cost them a crew member—Harry Manning. The reason released to the press was that Manning had to be back at his job. But Manning later said he quit because he had lost faith in Amelia’s skill as a pilot and was fed up with her “bullheadedness.” Whatever the reason, Manning’s absence left Fred Noonan as sole navigator.

More important, Amelia was forced to change her course. Now she would have to fly west to east, because the later starting date meant that the weather patterns—storms and winds—would be different.

“Now everything must be worked out again,” remarked George. “New maps and charts; new stores and gasoline and spare parts; new permissions and official documents and headaches for the husband.”

On May 21, 1937, Amelia took off for Miami from Oakland on the first leg of her second world flight attempt. With her were George, Fred Noonan and Bo McKneely, a flight mechanic. As the three flew eastward across the country, they paid close attention to the plane’s performance. “We planned to shake out any bugs in Florida,” explained Amelia.

They spent a week in Miami while McKneely and other mechanics went over the plane. They tinkered with the fuel pumps and the landing gear. They also changed a radio antenna in hopes of increasing the distance it could transmit messages. George and Amelia, meanwhile, did a little sunbathing and went fishing on a friend’s yacht.

On June 1, in the dark of early morning, Amelia, Fred and George drove to the airport. They loaded a small amount of luggage into the Electra, along with two thermoses of tomato juice. Then George and Amelia slipped into the hangar for a private goodbye. “There in the dim chill we perched briefly on cold concrete steps, her hands in mine,” he recalled. “There is very little one says at such times.”

When the mechanic called that all was ready, Amelia walked out to the airplane. “She seemed to me very small and slim and feminine,” said George. Then Amelia and Fred climbed into the plane, and she started the ship’s two engines. Amelia “exuded confidence and smiles,” recalled one of the bystanders.

George “did not.” Perhaps he was recalling his wife’s words from the night before. “When I go,” she had said, “I’d like best to go in my plane. Quickly.”

George paced nervously back and forth on the tarmac until the silver plane disappeared into the sky. Ever after, he would remember his wife’s eyes, “clear with the good light of the adventure that lay before her.”