TWO

A Century of Blood Group Science

Since their discovery at the beginning of the twentieth century, the ABO blood groups have emerged as the most reliable measure of human individuality and diversity. Their influence spans the entire spectrum of the physiological, psychological, and social orders.

Knowledge of their significance bridges many of the chasms in our understanding of human life—from how we have survived to the way we interact with our environment. The blood groups allow us to follow humanity’s many migrations across this ancient planet.

As we look at the unraveling of the mysteries of the blood groups during the past century, we can see the patchwork of human identity come together, piece by piece, confirming the interrelatedness of biology and destiny. It has been a fascinating and provocative journey.

The Discovery of ABO Blood Groups

The idea that blood circulated throughout the body was first proposed in 1628 by Englishman William Harvey, who published his theories in his famous book On the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals. Harvey was a student of Hieronymus Fabricius, an esteemed scientist and surgeon at the University of Padua in Italy. Fabricius, an ardent anatomist, had observed the one-way valves in veins, but had not figured out exactly what their role was. The popular belief of the day held that blood was circulated by a sort of pulsing action of the arteries.

From knowledge gained on the battlefield, early physicians knew that an extreme loss of blood produced shock and death. By the sixteenth century, physicians were attempting to replace blood lost in surgery or battle with the blood of a healthy donor. However, it was immediately recognized that success or failure was wildly unpredictable; some of these early attempts at transfusion succeeded in spectacular fashion, while others only seemed to hasten the demise of the patient. In their attempts to find a predictable way to exchange blood, physicians even tried using the blood of other animals, such as lambs, dogs and rabbits. Even milk and salt water were used. Unfortunately, most of the time these variations were terrible failures. Until the twentieth century, loss of blood was the most frequent cause of death in childbirth and on the battlefield.

Then, in 1888, at the University of Dorpat (now Tartu) in Estonia, a researcher doing work on his doctoral thesis made a discovery that would provide a vital clue to the mystery. While studying the toxicity of castor oil on laboratory animals, Herman Stillmark was shaken by the extreme suffering the animals endured. He decided to attempt his experiments on cell cultures instead of live animals. When Stillmark mixed an extract of castor seeds with blood, he made a startling observation: the red blood cells were agglutinated—that is, they clumped together, “like in clotting”‘. Stillmark discovered that the agglutination by castor bean seeds occurred in some animal species but not in others and that castor seeds could also agglutinate liver cells, skin cells and white blood cells of some species as well. What Stillmark had discovered was for many years termed a “toxic principle” in the plant, and it was more than a half century before the protein responsible for these toxic effects was effectively isolated and given the name ricin, from the Latin name for castor beans (Ricinus communis). The discovery of agglutination was an important medical breakthrough. For the first time, a direct reaction between other substances and blood had been demonstrated.

Stillmark’s work started a series of theses and papers at the University that investigated other agglutinating toxins. In 1891 it was discovered that the jequirty plant (Abrus precatorius) also possessed agglutinating properties. Croton, a third toxin isolated from the seeds of the “Physic-nut,” Croton tiglium, was also shown to have differences in behavior toward different animal blood cells. Some red blood cells were simply destroyed (rabbit, crow), some strongly agglutinated (ox, pig, sheep, pike, perch, and frog), some moderately agglutinated (cat), and some very slightly agglutinated (human).

These early papers on agglutination by plant toxins had a stimulating effect on the burgeoning science of immunology and correlated with other earlier findings that described other agglutinating proteins from animal origin, such as many snake venoms.

This immediately caught the attention of German bacteriologist Pat1 Erlich, who recognized that he could investigate certain immunologic problems using plant agglutinins rather than relying on bacterial toxins, such as diphtheria. Using abrin and ricin, Ehrlich carried out a number of experiments that established some of the fundamental concepts of immunology. For example, rabbits fed small amounts of jequirty seeds developed a certain degree of immunity against the abrin, and injecting abrin intravenously could increase their immunity. By this experiment Ehrlich was able to demonstrate the specificity of serum proteins (later known as antibodies) found in the serum of animals after the administration of abrin and ricin. For example, anti-abrin could neutralize the activity of abrin, but not that of ricin, and vice versa. The specificity of the basic antibody molecule and the induction of tolerance remain to this day the basic cornerstones of immunology.

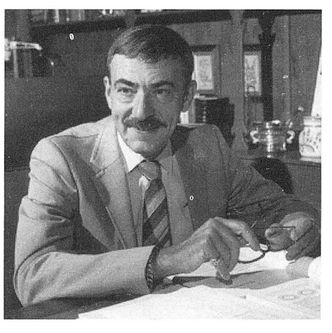

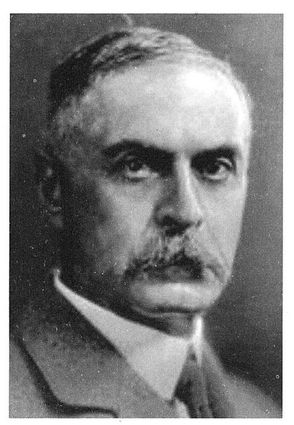

Dr. Karl Landsteiner received the Noble Prize in 1930 for his discovery of ABO blood group antigens and antibodies.

Erhlich’s findings concerning the specificity of most antibody molecules also paved the way for the discovery of the ABO blood groups twelve years later, by establishing the dynamics of what would become known as antigen-antibody reaction. In 1900, Dr. Karl Landsteiner, an Austrian-American physician and scientist, observed that when blood from different individuals was mixed, agglutination of the red cells took place—in some cases, but not in others. From these diverse reactions, it was possible to distinguish three distinct blood groups, O, A, and B. A fourth group, AB, would soon be added. For the first time, transfusions could occur in a safe and predictable manner. Considering the sheer number of human lives saved by Landsteiner’s discovery, it ranks as one of the greatest medical breakthroughs of all time—one for which Landsteiner would receive the Nobel Prize in 1930. With Philip Levine and Alexander Weiner, he would go on to discover the Rh blood system in 1946, thus resolving another puzzling complication of maternal-fetal reactions.

Independently of Landsteiner, Jan Jansky, a Czech doctor of medicine and professor at Charles University in Prague, was simultaneously reaching similar conclusions at the beginning of the century. Jansky, a specialist in the field of neurology and psychiatry, was analyzing the blood of more than 3,000 subjects to learn whether he could detect coagulation differences in the blood of schizophrenics and other psychotics. In the process of his investigation, Jansky noted four distinct blood groupings, and published his work on groups O, A, B, and AB in 1907.

More Than Just Transfusions

While the implications of these discoveries for safe blood transfusions was clear, Landsteiner’s curiosity about blood group reactions took him into wider territories. Blending Stillmark’s research on agglutination and Ehrlich’s research on immunology with his own findings on blood group reactions, he began experimenting with different substances and their impact on red blood cells. In 1908, he showed that small amounts of an agglutinin from the common lentil bean would clump the red blood cells of a rabbit, but even high amounts had no effect on the red blood cells of pigeons. He was also able to demonstrate that plant agglutinins attached to red blood cells could be liberated by raising the temperature to 50°C or by treating the agglutinated cells with pig gut mucus (providentially enough, a rich source of the blood group A antigen). Landsteiner was prepared to publish his findings showing the link between plant substances and blood groups in 1914, but war intervened and his work would not see print until 1933.

Although he appeared to have recognized the reactivity between certain plant toxins and red blood cells, Lansteiner apparently did not seem to search for any relationship that would have made them applicable as blood typing tools. In the four decades following his discovery, little new research was conducted, although a few new sources of agglutinins were discovered, including soy beans, lima beans, and peanuts.

However, in 1945 William Clouser Boyd, Ph.D., working at Boston University’s School of Medicine, discovered that some agglutinins can be blood group specific, being able to clump the blood of one type but not of another. The agglutinin found in lima beans clumped only type A red blood cells, but not those of type O or B. Boyd coined the term lectin to mean any agglutinin capable of clumping cells by linking up their surface sugars. Lectin is derived from the Latin word legere , which means “to pick or choose.” Lectins have very specific tastes when it comes to agglutination, only working on very specific combinations of sugars, much like a lock and its particular key.

As Boyd himself described in a 1970 issue of the Annals of the NY Academy of Science, his discovery of blood group—specific lectins came as he studied a table Landsteiner had used to summarize his animal data.

TABLE I. Titers of different plant agglutinins for the red cells of different species

“One day toward the end of 1945, looking at this table in the second English edition of Landsteiner’s book, I was seized with the idea that if such extracts could show species specificity, they might even show individual specificity; that is, they might possibly affect the red cells of some individuals of a species and not affect others of the same species. Therefore, I asked one of my assistants to go out to the corner grocery store and buy some dried lima beans. Why I said lima beans instead of the more common pea beans or kidney beans I shall never know. But if we had bought practically any other bean we would not have discovered anything new.

“The lima beans were ground and extracted with salt solution. The resulting extract agglutinated erythrocytes of some human individuals, but those of others only weakly, if at all. It was immediately evident that the differences were correlated with blood groups.

“The ease with which this discovery was made misled me, and aside from a rather oblique reference to it in the second edition of my Fundamentals of Immunology, which I was working on at the time, I did not publish this observation until 1949, when I reported on an investigation of 262 varieties of plants belonging to 63 families and 186 genera.

“I proposed that these blood-antigen-specific plant agglutinins (which are also specific precipitins) be called ”lectins“—from the Latin legere, to pick out or choose—intending thus to call attention to their specificity without begging the question as to their nature.”

Blood Groups and Their Human Distributions

The first scientific study of blood group distribution was first attempted by Ludwik and Hanka Hirschfeld, a Polish husband-wife team of immunologists, during World War I2. Working among the ethnically diverse Allied forces stationed at Salonika, Greece, the Hirschfelds used the new knowledge of blood groups to study racial and nationality characteristics. They systematically analyzed the blood groups of several different ethnic continents among soldiers in the English and French colonial armies, including Vietnamese, Senegalese, Indian, and various other war prisoners. Each group contained over 500 or more subjects. They found, for example, that the rate of blood group B ranged from a low of 7.2% of the population of English subjects to a high of 41.2% in Indians, and that Western Europeans in general had a lower incidence of blood group B than Balkan Slavs, who had a lower incidence than Russians, Turks, and Jews, who again had a lower occurrence than Vietnamese and Indians. The distribution of blood group AB essentially followed the same pattern, with a low of 3% to 5% in Western Europeans and a high of 8.5% in Indians.

Blood groups A and O were essentially the reverse of groups B and AB. The percentage of group A remained fairly consistent at 40% among Europeans, Balkan Slavs, and Arabs, while being quite low among West Africans, Vietnamese, and Indians. Forty-six percent of the English population tested were group O, which accounted for only 31.3% of the Indians tested.

Modern analysis, largely derived from blood bank records, probably contains the blood groups of more than 20 million individuals from around the world. Yet these large numbers can do no more than confirm the original observations of the Hirschfelds. Interestingly, at the time no scientific publication felt compelled to publish their material, which for a while languished in an obscure anthropology journal.

In the 1920s several anthropologists first attempted racial classification based on blood groups. Based on earlier work, in 1929 Laurance Snyder published a book called Blood Grouping in Relationship to Clinical and Legal Medicine3 in which he proposed a comprehensive classification system based on blood group. This book was especially interesting because it largely focused on the distribution of the ABO groups, the only tool to be had at the time. The Rh and MN groups had yet to be discovered.

Perhaps because of the chaotic aftermath of World War I and the Depression, the subsequent three decades saw little interest or activity in using the blood groups as an anthropological tool.

In 1950, William Boyd, who was proving himself to be a man of diverse interests and abilities, used his prior work with blood groups to combat racist notions that predominated in America. Collaborating with noted science fiction writer Isaac Asimov, Ph.D., he published Races and People4, a seminal work on the subject. Boyd contended that blood groups served as a far more reliable determination of race than other measures, such as skin color and national origin. He cited four reasons for this conclusion, all of which resonated for the times. First, blood group was a hidden characteristic. One couldn’t determine a person’s blood group by merely looking at him. It prevented judgments made on superficial and prejudicial bases. Second, unlike other physical characteristics, blood groups were inherited in precise ways. Third, blood groups remained intact from the moment of fertilization until death. They were permanent. Finally, blood groups served as conclusive evidence of the ways humans mixed with one another throughout history. There was no such thing as “purity” of race. The various blood groups were found all over the world. The only factor that changed was the frequency of their occurrence.

Earlier, Boyd analyzed the ABO blood group system, along with two minor systems, MN and Rh, that had been subsequently identified5. (See chapter 3.) From his analysis he isolated six “genetic races,” following patterns of immigration that would have been impossible to track by using skin color or other obvious characteristics:

TABLE II. Boyd’s Classifications

Early European group: Possessing the highest incidence (over 30%) of the Rh-negative gene, probably no group B, and a relatively high incidence of group O. The gene for blood group N was possibly somewhat higher than in present-day Europeans. This group is represented today by its modern descendants, the Basques.

European (Caucasoid) group: Possessing the next highest incidence of the Rh-negative gene and a relatively high incidence of group A2, with moderate frequencies of other blood group genes. Normal frequencies of the gene for blood group M.

African (Negroid) group: Possessing a tremendously high incidence of a rare type of Rh positive gene, RhO, and a moderate frequency of Rh negative; relatively high incidence of group A2 and the rare intermediate types of group A, and a rather high incidence of group B.

Asiatic (Mongolian) group: Possessing high frequencies of group B, and little if any of the genes for group A2 and Rh-negative.

American Indian group: Possessing little or no group A and probably no B or Rh-negative. Very high rates of group O.

Australoid group: Possessing high incidence of group A1, but not A2 or Rh-negative; high incidence of the group N gene.

Boyd’s classification made more sense than the earlier classification systems because it also fit the geographic distributions of the individual races more accurately.

In the 1950s, as emphasis shifted to genetic characteristics, scientific interest increased in the blood groups and other markers that have known genetic bases. In the 1960s, a brilliant Italian population geneticist named Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza produced a “tree” of human evolution, based largely on genetic evidence collected over the decades, primarily blood group studies. Cavalli-Sforza collected blood group data in the villages and mountain communities around Parma, Italy. Using the well-established network of Catholic parishes, he solicited the support of parish priests in blood-typing parishioners—often in sacristies after Sunday Mass. The branches of Cavalli-Sforza’s tree spread from a common ancestor in Africa to Asia, Australia, and North America. Other branches from Africa spread to the European areas, replacing Neanderthals as the original population source. Cavalli-Sforza’s research added to the evidence that, contrary to popular belief, races were not genetically distinct, but rather a mix with only superficial distinctions. He would later write that Europeans, drawing from both African and Asian ancestry, were the most genetically mixed-up race on earth.

He used this fact to make a pointed dig at Arthur de Gobineau, a 19th-century French author whose work had influenced German racism. De Goubineau “would die of rage and shame at this suggestion,” he wrote gleefully, “since he believed that Europeans ... were the most genetically pure race, most intellectually gifted and the least weakened by racial mixing.”

Frank Livingstone, one of the premier blood group paleoserologists, even rejected the concept of race altogether6,7. Livingstone theorized that although biological variability existed between the populations of organisms comprising a species, this variability did not conform to the discrete packages we call races. Rather, these distinctions were “clines”—gradients of physiological change in a group of related organisms, usually along a line of environmental transition.

In tracking the course of humanity using blood groups, the early paleoserologists were able to draw significant conclusions about how the human race survived. A. E. Mourant, a physician and anthropologist who published two key works, Blood Groups and Disease8 and Blood Relations: Blood Groups and Anthropology9, collected much of the available material on the subject. There is good evidence for considerable effects of selection on blood group distribution. Infection undoubtedly accounted for the majority of natural selection in prehistoric populations. This can be explained by the phenomenon of horror autotoxicus —that is, the body’s inherent aversion to producing antibodies to self antigens.

Mourant was the first to hypothesize that the relatively high distribution of group A in areas with historically high incidence of plague (Turkey, Greece, Italy) would point to selective disadvantage for group O, proven immunochemically by blood group studies on various Yersinia species. Antigenic similarity exists between the blood groups and a great variety of bacterial, rickettsial, and helminthic species, including typhoid, streptococci (group A), staphylococci (group O), Shigella , and Proteus. Strong proof for the theory that blood group was a critical influence on the survival of early humanity is the fact that virtually every infectious disease known to influence population demographics (malaria, cholera, typhus, smallpox, influenza, and tuberculosis) has had a “preferred” blood group that is especially susceptible and an opposing blood group that is resistant. Many experts have made strong arguments that the pressure applied by infectious diseases along blood group lines has been one of the factors, if not the primary factor, influencing natural selection and blood group distributions.

Blood Groups and Personality: The Science and the Pseudoscience

While physical anthropologists were tracing the evolution of the human race using blood groups, others were exploring the influence of blood groups from another perspective. The twentieth century had also seen the flowering of a new kind of science—one that sought to explain the mysteries of the mind in addition to the mysteries of the body. Inevitably, blood groups emerged as a subject of investigation. In the 1920s, Takeji Furukawa, a Japanese psychology professor, studied relations between blood group and character10. Furukawa proposed a theory on the relation between blood groups and temperament. He majored in experimental education in college, and upon his employment at a women’s high school he worked in its administration office. He came to believe that the temperamental differences of applicants were responsible for the inability to predict school performance from the results of their entrance examinations. He was from a family of many doctors, and was familiar with blood groups, the newest physiological discovery of the day. Furukawa published some of his work in the German Journal of Applied Psychology in 1931 and so influenced several European psychologists to begin to examine the concept in greater detail. German psychologist Karl H. Gobber took Furukawa’s work to deeper levels. In Switzerland, Dr. K. Fritz Schaer used the students of the Swiss Military Academy as test subjects in researching blood groups and personality. However, considering the fascist tidal wave that was washing over Germany and was soon to engulf Europe and the world in its brutal grip, Furukawa’s work became essentially lost in the maelstrom for a couple of decades.

Two major figures in psychology, Raymond Cattell11,12 and Hans Eysenck13, would later study blood groups peripherally in the course of their work on personality. Both were interested in studying personality as an organic, biochemical function rather than as a product of socialization and upbringing.

Cattell made several significant contributions to the development of research tools and techniques that tracked the individual differences in cognitive abilities, personality, and motivation. He developed the 16 Personality Factor (16PF) personality assessment device, designed to evaluate the personality patterns of a “normal” adult, which is still in wide use today.

In 1964 and again in 1980, Cattell studied blood groups using his 16PF system. A sample of 323 Caucasian Australians was characterized with respect to 17 genetic systems (including 7 blood groups) and 21 psychological variables. His results showed that:

1. Blood group AB individuals were significantly more self-sufficient and group-independent than types O, A or B.

2. Blood group A individuals were more prone to severe anxiety than blood group O individuals.

Using Cattell’s 16PF tool, another researcher studied the relationship between ABO blood group and personality factors in 547 south Mississippi schoolchildren. It was found that the mean scores for each personality factored differed by ABO blood type. Blood group O students were found to be more tense than blood group A or blood group B students. On the other hand, blood group AB students were the most tense of all14.

Psychologist Hans Eysenck, who was born in Berlin, studied in France and at London University, and was professor of psychology at London University from 1955 to 1983, similarly pioneered the idea that genetic factors play a large part in determining the psychological differences between people. Eysenck’s major contribution to psychology was his theory of personality, sometimes called the PEN System (Psychoticism, Extroversion, and Neuroticism). According to Eysenck, these variables were the result of physiological and chemical preferences; for example, introverts have higher levels of activity in the corticoreticular loop of the brain, and thus are chronically more cortically aroused, than extroverts.

Eysenck looked at differences between nationalities in their occurrences of particular personality characteristics as a reflection of the rates of certain ABO blood groups in their populations. He used earlier studies that showed significant differences in the frequency of the ABO blood groups among European introverts and extroverts, and between highly emotional and relaxed people. These results showed that emotionality was significantly more common in blood group B individuals than in blood group A individuals, and that introversion was more common in blood group AB than the other blood groups.

In one study, Eysenck looked at two population samples, one British, the other Japanese. Since previous studies had shown that Japanese samples were more naturally introverted and more neurotic than British samples, he predicted that the Japanese, as compared to the British, would have a higher proportion of blood group AB and a lower ratio of blood group A to blood group B. This was confirmed by looking at the established blood group frequencies for the two countries.

Taken as a whole, these investigations into blood groups and personality caused barely a ripple in the growing field of psychology. Popular interest in the subject did not occur until 1971, when Masahiko Nomi, a Japanese journalist, wrote a series of popular books on the subject of personality and blood type. Nomi’s work is typically uncontrolled and largely anecdotal; one never gets a clear idea of exactly how he arrived at his conclusions. Because of this he has been heavily assailed by the Japanese psychological community, although his books are phenomenally popular15.

Although the effects of blood groups on such a complicated aspect of expression as personality continue to remain unclear and contradictory, they may be just the tip of a much bigger iceberg—the relationship that occurs between ABO blood group and stress at the genetic level. Here observations achieved some credibility in recent years, when a moderate number of studies linked ABO blood groups to a diverse series of mental disorders, including associations between blood group O and bipolar disorder16-19 and blood group A and obsessive-compulsive disorder20-21. Other studies implied that the genetics of ABO blood groups might influence the amount and kind of neurochemicals and hormones secreted in conditions of stress. For example, blood group O individuals are known to respond to stress by secreting large amounts of catecholamines, such as adrenaline. In addition, there is evidence that they tend to eliminate adrenaline less efficiently under stress than their A, B, and AB counterparts. Because of high circulating levels of adrenaline, it would not be surprising to find that the incidence of “type A behavior” is actually higher in blood group O, a fact that has been shown for young men recovering from acute heart attacks22.

Blood group A and B individuals were shown to manufacture higher levels of the adrenal stress hormone cortisol when under stress, and blood group A individuals were least effective at removing excess cortisol over time when compared with the other blood groups. High levels of cortisol have been linked with obsessive-like thought patterns, a higher incidence of heart disease, metabolic inefficiency, and lower immune function23,24. In addition, the blood of group A individuals has been shown to become more viscous when under stress when compared to the other ABO blood groups25. Perhaps this is the result in part of a known association between group A and a tendency toward higher levels of various clotting factors 26.

First Links Between Blood Groups and Biological Function

As early as 1921, a study in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology27 examined blood group frequencies in patients suffering from various types of carcinoma and concluded individuals of group AB were more prone to cancer in general, a finding echoed by two later studies, done in the 1930s28-29. This was the beginning of a growing body of raw data showing blood group—specific propensities for disease, but these studies were fraught with difficulty, largely due to confounding factors such as ethnic or geographic factors. In addition, many times a negative result was reached that was later shown to be the result of faulty statistical analysis. For example, stimulated by the first cancer study, a larger study done at the Mayo Clinic in the 1920s analyzed the blood groups of 2,446 patients and concluded that there was no association between blood group and cancer as previously reported, and in fact no association between blood group and disease at all30. Among the diseases examined and included in the negative results were several, such as pernicious anemia and stomach ulcers, for which there is no longer any doubt about a strong link with blood group. Had the Mayo investigators used more reliable statistical tools, the blood group associations would have been discovered. Unfortunately, the Mayo Clinic report sidetracked interest in the study of blood groups and disease for a considerable period of time.

The first strong link between ABO blood groups and a non-blood-related disease was reported in 1936 by Luigi Ugelli, an Italian physiologist. Ugelli found the incidence of bleeding ulcers highest in men who were blood group O, an association that has now been confirmed with extensive studies31.

After a hiatus during World War II, interest again developed in looking at the link between blood groups and disease. In 1953, when researchers demonstrated an association between group A and higher incidences of stomach carcinoma32, there was a resurgence of clinical interest in blood group disease studies, which skyrocketed during the late 1950s and 1960s. The use of newer, more powerful analytic tools to study large populations for the first time provided the mathematical basis for accurate research. In a paper published in 196033, researchers demonstrated a “strikingly high” increase of group O among ulcer sufferers compared to controls, with a correspondingly lower incidence of the other blood groups, a finding corroborated by numerous other researchers34. In addition to these links with diseases of the digestive tract, researchers also began to find associations between blood groups and physiological functions. Blood group O was shown to have higher levels of stomach hydrochloric acid34-36, pepsinogen37, and gastrin—all important digestive factors necessary for proper protein digestion and the intestinal enzyme alkaline phosphatase38, an important digestive enzyme necessary for fat absorption. Blood group A was shown to have higher levels of blood clotting factors and a greater incidence of heart disease and elevated cholesterol39.

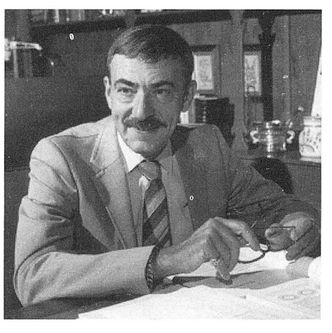

James D‘Adamo, N.D.

My father, James D‘Adamo, N.D., was the first to advance the theory that the ABO blood groups could be employed as a method of optimizing diet. During the 1960s he noticed that although many patients did well on strict vegetarian and low-fat diets, a certain number did not appear to improve, and several did poorly or even worsened. A sensitive man with keen powers of deduction and insight, he reasoned that there should be some sort of “key” that he could use to determine differences in the dietary needs of his patients. He rationalized that since blood was the great source of nourishment to the body, perhaps some aspect of the blood could help to identify these differences.

Through the years and with countless patients, a pattern emerged. Patients who were blood group A seemed to do poorly on high-protein diets consisting of large amounts of meat, but did well on vegetable proteins such as soy and tofu. When group A patients ate large amounts of dairy, it tended to produce copious amounts of mucous discharge in their sinuses and respiratory passages. When they increased their level of physical activity and exercise, group As tended to feel less well than when they did lighter forms of exercise, such as Hatha yoga.

On the other hand, group O patients tended to thrive on high-protein diets, and they often stated that high-intensity activities, such as jogging and aerobics, energized them and improved their moods. In 1980, my father condensed his observations and dietary recommendations into a book titled One Man’s Food, inspired by the saying “One man’s food may be another man’s poison.”

At the time of the publication of my father’s book, I was in my third year of naturopathic studies at Seattle’s John Bastyr College. In 1982, for a Clinical Rounds requirement in my senior year, I scanned the medical literature to see if there was a correlation between ABO blood group and a predilection for certain diseases, and whether any of this supported my father’s diet theory. As I knew that his book was based on his own subjective impressions of the blood types, and not on any objective methods of evaluation, I wasn’t sure what I would find.

After an extensive literature search at the University of Washington’s Health Sciences Library, I collected a large amount of seemingly unrelated information about certain rare diseases that were associated with blood type, and several common diseases that apparently were not. I also found a large number of digestive diseases and functions linked to blood type—information I had not learned in medical school. These were the first revelations that suggested a scientific basis for my father’s empirical observations.

As I continued my investigation, I found other key correlations and I published my data in 1982 in a paper titled “Diet, Disease and the ABO Blood Groups: A Review of the Literature.”

I spent the next twenty years continuing my research, in particular advancing the study of blood group—specific lectins and their effects on digestion and immunity. In the clinical setting of my practice, I used this increasingly viable science to successfully treat thousands of patients. In late 1996, I published Eat Right 4 Your Type: The Individualized Diet Solution to Straying Healthy, Living Longer and Achieving Your Ideal Weight (Putnam).

By that point, there were more than a thousand published studies on the associations of blood groups and disease. It was difficult to argue with the general pattern that emerged from the large body of statistical data on malignancy, coagulation, and infection. Discoveries in membrane chemistry, tumor immunology, and infectious disease (especially relating to bacterial receptors) added a scientific rationale and bolstered the credibility of earlier statistical studies. Some of the more recent findings on parasitic/bacterial/viral receptors, the hematological abnormalities seen when high frequency blood group antigens are missing, and the association with immunologically important proteins were most convincing in demonstrating a blood group association.

Yet, even as the body of research continued to expand, linking blood group individuality to diet and disease, the mainstream medical community largely remained unaware of the breakthroughs. In most medical schools, the study of ABO blood groups was still limited to its role as a complicating factor in transfusions—a limitation Landsteiner, Boyd, and others transcended almost a century ago.

By 2000, using the tools of the Internet, I had compiled a Blood Type Outcome Registry, consisting of nearly 4,000 reports from individuals of every blood type, based on the level of improvements they experienced in diseases and chronic conditions after using the blood type diet plans (see part 3). Many of these results were fortified by “hard” data, including blood tests and physician reports. The level of overall satisfaction reported was quite astounding: Regardless of blood group, a consistent 90% to 93% rate of overall satisfaction with the results of the diet was reported, with improvements in digestion, overall sense of energy and well-being, and weight loss being the most common results reported. The significance of these findings goes beyond a simple degree of satisfaction or a beneficial health improvement. It scientifically challenges the validity of any “one size fits all” diet philosophy. Nine out of 10 blood group O individuals report beneficial results from a high-protein diet, while 9 out of 10 blood group A individuals report a similar rate of success with a predominantly low-protein diet.

One person’s food is indeed someone else’s poison.

The development of the nonprofit Institute for Human Individuality (IfHI) now promises to take the research even further. In alliance with the Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine, IfHI will do the large-scale clinical studies needed to evaluate the efficacy of the Blood Type Diet with regard to a variety of common chronic diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and several cancers.

Future History

As a new century dawns, it appears that widespread acceptance of blood group science will ultimately rely on the explosive discoveries being forged in DNA research and biotechnology. In essence, medical science may finally be catching up with the non-transfusion significance of the ABO blood groups. This is especially to be seen in the field of molecular oncology, the study of cancer on a molecular level. Here the ABO blood groups are assuming a greater role with the release of each scientific journal. For example, the finding that many tissues first signal their conversion into cancer cells by losing the ability to synthesize ABO antigens40,41 has furthered our understanding of the early, premalignant changes that cells undergo before they become deadly and begin to spread (metastasize).

Nanorobotics: The Future of Blood Groups?

Today we are witnessing even more remarkable possibilities for blood groups to play a role in every aspect of human health and healing. An exciting new technology called nanotechnology, which employs knowledge of the blood groups as one of its key determining factors, is about to make an enormous impact on how medicine will be practiced in the near future. Nanotechnology is the process of creating microscopic machines that will enter our bodies to perform specific tasks. They will intervene with disease and heal heretofore unreachable mechanisms deep within us—even the narrowest veins and tiniest cells will be open to this new medical miracle. Nano (meaning “incredibly small”) technology will be created by controlling the manufacture of individual atoms.

These manipulated biomolecules will become known as nanobots—robots of microscopic proportions. Researchers are currently working on the means to tailor devices and materials on the scale of billionths of a meter. They will eventually acquire the ability to engineer living structures, biological machines no larger than molecules such as DNA. In a time reminiscent of the film Fantastic Voyage, many medical futurists foresee tiny robotic biomolecules that will be placed into the body, perhaps engineered to destroy specific cancer cells or repair damaged DNA material. These nanobots will be programmed to identify specific ABO antigens as measures of identity, so they can instantly spot the mutations that cause disease.

The scattershot days of contemporary medical intervention may soon be considered as antique as the Model T Ford. Physicians may soon be able to design tiny tools to safely and effectively repair the damaged nanoscopic machinery of a diseased body, just as a mechanic works on a car’s engine today using tools that are on the same scale as the engine. It sounds like science fiction—and until recently it was—but it’s reaching the verge of possibility because teams of doctors and scientists are combining advances from biology and chemistry with the synthesis and fabrication of tools from chemical engineering and the microchip industry.

Robert A. Freitas is considered the father of nanomedicine, and he’s quite interested in using blood groups as determinants of individuality in the new field. As Freitas writes in his book Nanomedicine : “A nanorobot, searching for a particular set of approximately 30 blood group antigens, would require about three thousandths (3/1000) of a second to make the self/non-self determination for a particular red cell membrane it encountered. A nanorobot seeking to determine the complete blood group type of the membrane, and must in the worst case search all 254 known blood antigen types, would require at most 2 seconds to make these determinations”42. Perhaps in the near future, a biological microrobot may reassemble damaged genetic material, or destroy killer microbial invaders, reading blood group antigens to accomplish its task.

The very genetic factor that enabled the survival of our ancestors hundreds of thousands of years ago may soon be the source of technological miracles.

REFERENCES

1. Kocourek J. The Lectins: Properties, Function and Applications in Biology and Medicine. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1986.

2. Hirschfeld L, Hirschfeld H. Lancet II. 1919;:675-679.

3. Snyder L. Blood Grouping In Relationship to Clinical and Legal lVledicine. 1929.

4. Asimov I, Boyd WC. Races and People. New York: Abelard-Schuman; 1955.

5. Ibid.

6. Livingstone FB. On the non-existence of human race. Current Anthropology. 1962;3:279-281.

7. Livingstone FB. An analysis of the ABO blood group clines in Europe. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1969;31:1-9.

8. Mourant AE. Blood Groups and Disease. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press; 1979.

9. Mourant AE. Blood Relations: Blood groups and Anthropology . Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press; 1983.

10. Sato T, Watanabe Y. The Furukawa theory of blood-type and temperament: the origins of a temperament theory during the 1920s [in Japanese]. The Japanese Journal of Personality. 1995;3:51-65.

11. Cattell R.B. The relation of blood types to primary and secondary personality traits. The Nankind Quarterly. 1980; (21):35-51.

12. Cattell RB, Young HB, Houndelby JD. Blood groups and personality traits. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1964;16:397-402.

13. Eysenk HJ. National differences in personality as related to ABO blood group polymorphism. Psychological Reports. 1977;41:1257-1258.

14. Swan D, et al. The relationship between ABO blood type and factor of personality among south Mississippi ‘Anglo-Saxon’ school children. The Mazzkind Quarterly. 1980;20: 205-258.

15. Takuma T, Matsui Y. Ketsueki gata sureroetaipu ni tsuite [About blood type stereotype]. Jinbuzzgakuho. (Tokyo Metropolitan University) 1985;144:15-30.

16. Rihmer Z, Arato M. ABO blood groups in manic-depressive patients. J Affect Disord. 1981;3:1-7.

17. Mendlewicz J, et al. Minireview: molecular genetics in affective illness [review] Life Sci. 1993;52:231-242.

18. Mendlewicz J. [Contribution of biology to nosology of depressive states. Neurochemical, endocrine and genetic factors]. Acta Psychiatr Belg. 1978;78:724-735.

19. Oruc L, Ceric I, Furac I. [Genetics of manic depressive disorder]. Med Arh. 1996;50:45-47.

20. Rinieris PM, Stefanis CN, Rabavilas AD, Vaidakis NM. Obsessive-compulsive neurosis, anancastic symptomatology and ABO blood types. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1978;57:377-381.

21. Rinieris P, Stefanis C, Rabavilas A. Obsessional personality traits and ABO blood types. Neuropsychobiology. 1980;6: 128-31.

22. Neumann JK, Chi DS, Arbogast BW, Kostrzewa RM, Harvill LM. Relationship between blood groups and behavior patterns in men who have had myocardial infarction. South Med J. 1991;84:214-218.

23. Locong AH, Roberge AG. Cortisol and catecholamines response to venisection by humans with different blood groups. Clin Biochem. 1985;18:67-69.

24. Neumann JK, Arbogast BW, Chi DS, Arbogast LY. Effects of stress and blood type on cortisol and VLDL toxicity preventing activity. Psychosom Med. 1992;54:612-619.

25. Dintenfass L, Zador I. Effect of stress and anxiety on thrombus formation and blood viscosity factors. Bibl Haematol. 1975;(41):133-139.

26. Meade TW, Cooper JA, Stirling Y, Howarth DJ, Ruddock V, Miller GJ. Factor VIII, ABO blood group and the incidence of ischaemic heart disease. Br J Haematol. 1994; 88:601-607.

27. Alexander W. Br J Exp Path. 1921;2:66.

28. Mithra PN. Ind J Med. Res. 1933;20:995-1004.

29. Pautienis PN. Medicina Kaunas. 1937;8:1—12.

30. Buchanan Higley. Br J Exp Path. 1921;2:227.

31. Ugelli I. Polyclinico (sez prat). 1936;(43):1591.

32. Bentall A, Roberts F. Br J Med. 1953:799—801.

33. Shahid A, Zuberi SJ, Siddiqui AA, Waqar MA. Genetic markers and duodenal ulcer: JPMA J Pak Med Assoc. 1997;47:135—137.

34. Purohit GL, Shukla KC. Correlation of blood groups with gastric acidity in normals. Indian J. Med Sci. 1960;(14): 522—524.

35. Sievers M. Hereditary aspects of gastric secretory function I. Amer. J. Med. 1959;27:246—255.

36. Sievers M. Hereditary aspects of gastric secretory function II. Amer. J. Med. 1959;27:256—265.

37. Pals G, Defize J, Pronk JC, et al. Relations between serum pepsinogen levels, pepsinogen phenotypes, ABO blood groups, age and sex in blood donors. Ann Hum Biol. 1985; 12:403—411.

38. Domar U, Hirano K, Stigbrand T. Serum levels of human alkaline phosphatase isozymes in relation to blood groups. Clin Chim Acta. 1991;203:305—313.

39. Meade TW, Cooper JA, Stirling Y, Howarth DJ, Ruddock V, Miller GJ. Factor VIII, ABO blood group and the incidence of ischaemic heart disease. Br J Haematol. 1994; 88:601—607.

40. Greenwell P. Blood group antigens: molecules seeking a function? Glycoconj J. 1997;14:159—173.

41. Dabelsteen E. Cell surface carbohydrates as prognostic markers in human carcinomas. J Pathol. 1996;179:358—369.

42. Freitas R. Basic capabilities. In: Nanomedicine. Vol. 1. 1st ed. Georgetown, TX: Landes Bioscience; 1999.