Who wants it most

‘Champions aren’t made in gyms. Champions are made from something they have deep inside them. A desire, a dream, a vision.’

Muhammad Ali

Not so long ago, most people had no idea who Shelly-Ann Fraser was going to become. She was a middling high school athlete – nothing to write home about. There was every indication that she was just another Jamaican teenager without much of a future. One person wanted to change this. Stephen Francis observed then eighteen-year-old Shelly-Ann Fraser at a track meet just outside Kingston and was convinced that he had seen the beginnings of true greatness. Her times were not exactly impressive, but even so, he sensed there was something trying to get out, something the other coaches had overlooked when they had assessed her and found her lacking. He decided to offer Shelly-Ann a place in his murderous training sessions. Their collaboration quickly produced results, and a few years later at Jamaica’s Olympic trials in early 2008, Shelly-Ann Fraser, who at that time only ranked number 70 in the world, sensationally beat Jamaica’s unchallenged queen of the sprint, Veronica Campbell-Brown.

‘Where did she come from?’ asked an astonished sprinting world, before concluding that she must be one of those one-hit wonders that pops up from time to time, only to disappear again without trace. But Shelly-Ann Fraser was to prove that she was anything but a one-hit wonder. At the Beijing Olympics she shattered any doubts about her ability to perform consistently by becoming the first Jamaican woman ever to win the 100 metres Olympic gold. She did it again one year on at the World Championships in Berlin, becoming world champion with a time of 10.73 – the fourth fastest time ever.

In other words, the woman with the characteristic short, explosive sprinter’s legs now jogging towards me across the MVP Track and Field Club’s grass track after the morning’s interval training is nothing less than a superstar. Shelly-Ann Fraser is a little woman with a big smile. Her accommodating, rather shy personality is reminiscent of an unconcerned college girl, but behind her childish enthusiasm you can also sense how serious she is. She has a mental toughness that did not come about by chance. Her journey to becoming the fastest woman on earth has been anything but smooth and effortless.

Shelly-Ann grew up in one of Jamaica’s toughest inner-city communities known as Waterhouse, where she lived in a one-room tenement, sleeping four in a bed with her mum and two brothers.

‘Waterhouse is one of the poorest communities in Jamaica. A really violent place, overpopulated, children having children, a lot of crime,’ she explains as we sit and talk in the shade at the training ground.

Several of Shelly-Ann’s friends and family were caught up in the killings; one of her cousins was shot dead only a few streets away from where she lived.

Her mother Maxime, one of a family of fourteen, had been an athlete herself as a young girl but, like so many other girls in Waterhouse, had to stop when she became pregnant as a teenager with Shelly-Ann’s oldest brother Omar. Maxime’s early entry into the adult world with its obligations and responsibilities gave her the determination to ensure that her kids would not end up in Waterhouse’s roundabout of poverty.

‘My mother encouraged me a lot. I really love her because when nobody else was there, she always made sure to provide for us. It was hard for her; sometimes we didn’t have enough to eat. I ran at the school championships bare-footed because we couldn’t afford shoes.’

It didn’t take long for Shelly-Ann to realise that athletics could be her way out of Waterhouse. On a summer evening in Beijing in 2008, all those long, hard hours of work and dedication finally bore fruit. The barefoot kid who just a few years previously had had been living in poverty, surrounded by gangsters and violence, had written a new chapter in the history of athletics.

But her victory was far greater than that. The night she won Olympic gold in Beijing, the routine murders in Waterhouse – 30 in the previous seven months – and the drug wars in the neighbouring streets halted. The dark cloud above one of the world’s toughest criminal neighbourhoods simply disappeared for a few days. As Shelly-Ann Fraser explained to the Daily Mail after her Olympic triumph: ‘I didn’t become just another Waterhouse statistic but someone who could uplift the community, who showed something good could come from anywhere in Jamaica – even the ghetto.’

Her significance as a role model for the people of Waterhouse made a deep impression on her. ‘I have so much fire burning for my country,’ she tells me.

She plans to start a foundation for underprivileged children and wants to build a community centre in Waterhouse. She hopes to inspire the Jamaicans to lay down their weapons. She intends to fight to make it a woman’s as well as a man’s world, and she is currently studying to become a child psychologist.

‘When I go back to Waterhouse, I can see that I had a positive effect,’ she says. ‘It’s more united, I see more kids going to school, taking part in sport. It makes me proud and gives me a lot of motivation.’

The difference that makes the difference

A couple of days after my meeting with Shelly-Ann Fraser, I am sitting with Glen Mills on a bench in the sun outside Queen’s University in Kingston. He has just finished a training session with, among others, the phenomenal Usain Bolt and the new sprinting hope Yohan Blake.

In Jamaica, Glen Mills is known as the architect of Bolt’s success. He is the man who resurrected him after he came last in the 200 metres at the 2005 Helsinki World Championships and was deemed a failure.

After this debacle, Bolt contacted Mills. The rest is history. Since then, Usain Bolt has toppled one world record after another, and has always attributed his extraordinary performance to Glen Mills.

Since my conversation with Shelly-Ann I have been obsessed with what it is that actually makes the difference in the Olympic finals of the hundred metres. The sprinters know that they will only be a few hundredths of a second apart at the tape. A single blunder is enough to make the difference between coming in first or eighth. All will have been training like crazy to be fast enough. Motivation and concentration burn in the eyes of the sprinters as they place their feet on the blocks and prepare themselves for the crack of the starting pistol. In less than ten seconds it will all be over. But which factor, more than any other, determines who will be the winner?

I decided to put that question to Glen Mills. I expected a rather long, complex answer, perhaps something to do with a special sprinting technique, a superb start, a specific body type or something else along those lines. But he just looked me in the eye and said: ‘Who wants it most.’

Do you have grit?

Motivation is the emotional foundation of all excellence, no matter who you are or what it is you are striving to achieve. As we know, it takes 10,000 hours, or about a decade of practice, to become highly successful in most endeavours, from managing a company to becoming a world-class sprinter. It takes powerful commitment, and the secret to success is often to want something badly enough. Jack Welch, the former CEO of General Electric, once said: ‘Any company trying to compete … must figure out a way to engage the mind of every employee.’

When the Los Angeles Lakers suffered a crushing defeat last year at the Miami Heat in the American NBA league, the team’s star player, Kobe Bryant, stayed behind for an hour and a half at the stadium to train at the things he had been dissatisfied with in his game. When asked why he didn’t go home like all the other members of his team, his response to the NBA journalist Adrian Wojnarowski was to quote the Greek hero Achilles in the film Troy: ‘I want what all men want, I just want it more.’

That’s the way it is. If you want something badly enough you don’t have to worry about self-discipline and perseverance, they come to you naturally.

Countless researchers have endeavoured to solve the motivation mystery and find the recipe to ths irresistible drive, about which Glen Mills speaks and which Shelly-Ann Fraser and Kobe Bryant personify.

One of the most interesting studies of motivation was done by Angela Duckworth, Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania. As a college student, Duckworth developed a particular interest in neurobiology and became a teacher at a school for low-income children. Here she began to wonder why many of the children had reading skills that were four grade levels below average. They neither appeared less intelligent nor had lower IQs than other children. This mystery inspired Duckworth to return to university for a PhD. She contacted Martin Seligman, the father of the modern positive psychology movement, and together they began ground-breaking work to identify high achievers in a whole series of different fields, interviewing them and then describing the characteristics that seemed to typify them. These top performers were generally very different from each other, but did all seem to hold one characteristic in common: a determination to accomplish an ambitious, long-term goal despite the inevitable obstacles. Duckworth and Seligman noticed that people who accomplished great things usually combined a passion for a single mission with an unwavering dedication to achieving that mission, whatever the obstacles and however long it might take. Duckworth and Seligman decided to name this quality ‘grit’.

This is the same quality identified by the legendary psychologist Lewis Terman in the 1930s, when he followed a group of gifted boys from childhood to middle age. ‘Persistence in the accomplishment of ends’ was, according to Terman, what primarily differentiated them from less successful boys. More or less the same conclusion was drawn by Joseph Renzulli, director of the National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented, where they conducted one of the most widely cited studies of talent ever performed. Renzulli emphasised perseverance, endurance and hard work – which he referred to collectively as ‘task commitment’ – as a crucial element of what we typically call giftedness.

The persistence and motivation Duckworth and Seligman, Terman and Renzulli are talking about is a trait common to all the greatest performers in history, even among those who appear to have a gift that allows them to excel with very little effort. One such person is Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. His diaries contain a frequently cited passage in which he describes how an entire symphony appeared in his head, in its entirety. But as Jonathan Plucker, an educational psychologist at the University of Indiana noted: ‘No-one ever quotes the next paragraph, where he talks about how he refined the work for months.’

Angela Duckworth and Martin Seligman have shown in numerous contexts that grit is perhaps the best indicator of how well a student will manage in real-life academic settings. But the importance of grit goes far beyond academic settings – it seems to be crucial even in the military, for example. Duckworth and Seligman demonstrated that grit was the best indicator when it came to predicting who would complete the first, extremely exhausting, summer training session (known as Beast Barracks) at the United States Military Academy at West Point. In 2008 they distributed a grit questionnaire to all of the 1,223 cadets entering the training programme. It transpired that those who scored the most points in the grit questionnaire were also the ones who survived the demanding first few weeks at the academy. Traditional indicators such as high school class rank, SAT scores, athletic experience and faculty appraisal scores paled into insignificance in comparison to grit. As Duckworth put it: ‘Sticking with West Point doesn’t have as much to do with how smart you are as your character and motivation does.’

The power of role models

So it seems clear that motivation is essential for top performance, but where does it come from? If we can understand that then it will surely be easier to develop and sustain it in ourselves and others. Two American psychologists attempted to trigger a motivation explosion and the results of their study certainly give us a lot to think about.

In 2008 Geoffrey Cohen from the University of Colorado and his colleague Gregory Walton selected a group of first-year students at Yale, who were asked to read an article. The article was written by a former student by the name of Nathan Jackson, and told how he had arrived at college without a clue as to what kind of career he wanted to pursue. During his studies, however, he developed a great liking for maths and after leaving college he made a brilliant career for himself in mathematics as a recognised expert.

In Nathan Jackson’s story the students found a maths role model. However, Cohen and Walton had manipulated one aspect of the experiment.

At the bottom of the article they had inserted a small fact box with information about Jackson’s home town, educational background and date of birth. In half the articles they had changed Jackson’s date of birth to that of the student reading the document. The other half were given the article with Jackson’s correct date of birth. Cohen and Walton asked the students to solve a challenging – in actual fact unsolvable – maths problem after they had read the article. The idea was to test the students’ attitude and approach to the subject. How long and hard were they willing to work to solve an insoluble mathematical problem before they gave up?

All the students worked individually on the assignment and had no idea that they were being assessed. It turned out that the students who had read the article in which their date of birth matched that of Nathan Jackson showed a distinctly more positive and committed attitude to maths. They were persistent and worked 65 per cent longer on the unsolvable problem than their fellow students.

In other words: just because they shared the same date of birth as a maths expert they had read about, they were motivated to work harder. They didn’t know Nathan Jackson and had never met him, but all the same he became a subconscious role model who kindled their appetite for maths.

As Cohen and Walton concluded: ‘There is much to suggest that our motivation is kindled much less than we believe by our interests, passions or individual skills, but to a great extent by the social role models with whom we identify ourselves. People who connect with a role model become quite simply more motivated, even if they don’t know the person concerned.’

In the light of this discovery, one might maintain that the earlier in life you meet a suitable role model, the greater the chance of you becoming motivated enough to train for the number of hours required to lead to elite performance.

With this in mind it will probably not surprise you that role models for the young athletes were in evidence in all of the six Gold Mines I visited.

They did it. Why can’t you?

Every Jamaican has a picture etched in their minds of their countrywoman Deon Hemmings standing atop the rostrum at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics having won the women’s 400 metres hurdles and set a new Olympic record. She was the first Jamaican woman ever to win an Olympic gold medal. During the victory ceremony, she stood with her hand on her heart as the Jamaican flag was raised above the Olympic Stadium in Atlanta and the Jamaican national anthem was played. At the moment it hit her what she had achieved, tears begin to roll down her cheeks.

The main reason for the familiarity of this scene in Jamaica is that the video of the victory ceremony was subsequently shown in every cinema in the country, where it is traditional for everybody to stand while the national anthem is played. In other words, you couldn’t go to the cinema in Jamaica for eight years without seeing Deon Hemmings standing on the rostrum.

Back in 1996, Melanie Walker, Sherone Simpson and Shelly-Ann Fraser were little girls aged eleven, twelve and thirteen. They all went to the cinema with their parents and friends. On the big screen they repeatedly saw a perfect role model standing at the top of the Olympic rostrum in tears.

Just over ten years later, these three little girls, having grown up to become big stars, swept the competition off the track at the finals of the Beijing Olympics, to complete the 100 metres as numbers one, two and three.

I am not trying to saythat all you have to do is to throw weeping sports stars on the screen during prime time and then lean back and wait for Olympic gold medallists to spring up ten years later. But try to imagine what it does to children and young people when they are shown what they can become if they work hard enough – and what it means for their country if they do. Role models send a clear message: ‘We did it. Why can’t you?’

Deon Hemmings had exactly the same effect on young sprinters in Jamaica that Nathan Jackson had on the students at Yale. Role models are sparks that can light the fire of motivation.

In my experience, top performers are able to pinpoint extremely precisely the moment that they found inspiration and thought to themselves: ‘That’s what I want to be.’

As twice world champion hurdler Colin Jackson said in the BBC series The Making of Me: ‘I can still remember my parents sitting in front of the television screaming, shouting at Don Quarrie [the Jamaican sprinter], cheering him on to win the Olympic gold in the 200 metres in 1976. I looked at them and thought: “I want to be just like him”.’

Something similar happened to Ethiopian running legend Haile Gebrselassie. As a seven year old, he saw his countryman Miruts Yifter take the gold in both the 5,000 and the 10,000 metres at the 1980 Moscow Olympics. When he explained how that felt to me his words were almost identical to Colin Jackson’s: ‘I sat there thinking: “I want to be like him!”’

The Gold Mines are bursting with inspiring role models and cultural icons, who kindle motivation in entire generations. Spend some time in Jamaica, Ethiopia or Brazil and you will find that beneath the surface tiny seeds of motivation are constantly being planted. The High School Championships in Jamaica – the Champs for short – are a perfect example of this happening, and they made a deep impression on me.

The DNA of the sprinting powerhouse

Kingston, the National Stadium. More than 30,000 spectators are crammed in to the stands – it’s a seething witches’ cauldron of emotion. Weeks and months of pent-up expectation are finally being released. This is what the athletes from St Jago High School and the 120 other Jamaican schools have spent months training for. Down on the track the young runners are getting ready for the sprint of their lives. This is the stage onto which the 3,000 young Jamaican athletes march when they compete once a year for the title of king or queen in the High School Championships, which were held for the first time in 1910.

Which of these fifteen-year-old Jamaican girls and boys might, in a few years, take on the mantle of Jamaican sprinting success and beat yet more world records?

Next to the Olympics and the World Championships there is no event which obsesses the nation like this four-day competition. What sounds like an annual school sports day to the rest of the world is for Jamaicans the climax of the sporting year. It is so important that from the way Jamaicans talk you could be forgiven for thinking that it’s matter of life or death. Tension builds for weeks leading up to the competition. The Champs completely monopolise the front pages of the newspapers and the top stories on the TV news.

During the competition, everybody in Kingston – from hotel porters and bus drivers to the fruit salesmen and the homeless – discusses athletics. Everybody has an opinion about who will be the next Usain Bolt or Shelly-Ann Fraser. Bars and restaurants install huge TV screens so that those who are not able to get into the stadium can watch live broadcasts. Viewing figures approach 1.2 million in a country with a population of 2.8 million.

Inside the stadium, every school demonstrates its support for its athletes with drumming, giant banners and loud cheering. Emotions run high and frequently end in violent clashes on the streets after dark, after the last race has been run.

All the celebrated Jamaican sprinters turn out at the stadium every year for the event where everything started for them. It is here that the stars are born. Bolt, Fraser and the others all talk about the Champs as the experience that defined them as runners on their way to the top. It is in this extremely competitive environment that the foundations of their mental strength were laid.

‘It’s the biggest thing there is. It’s like the World Cup or the Olympics. It’s extremely competitive, especially the relay race. The atmosphere of the stadium changes completely when the relay starts. If you are not strong enough mentally you crack up,’ Usain Bolt said of his experiences in the Champs.

Or as five-times Olympic medallist Veronica Campbell-Brown put it: ‘If you can perform in front of a Champs crowd you can perform anywhere. When a Jamaican athlete enters a stadium to face a crowd of 80,000 people it’s just another day at the office.’

The Champs is the heart of Jamaica’s sprinting culture and the intensity there makes an American track meet resemble any old training session. In the United States, friends, family and a couple of coaches will be in attendance. At the Champs there are 30,000 spectators. As Glen Mills told me: ‘If you have what it takes to win the Champs and receive an ovation on the rostrum, you will do anything to get back up there again. It’s a feeling you will chase forever.’

The Champs is an event that lights a fire in the bellies of future super-sprinters. It’s an explosive cocktail of inspiring role models; ruthless competition that forces the best out of you; massive pressure that tests your psyche; and an adrenaline kick that you will want to chase for ever. If Martin Seligman and Angela Duckworth had been sitting in with me in the stands of the National Stadium in Kingston, they would see that the Champs are the perfect environment in which to develop grit. They demand rock-solid persistence and encourage people to raise the bar and perform at a higher level than they would have thought possible.

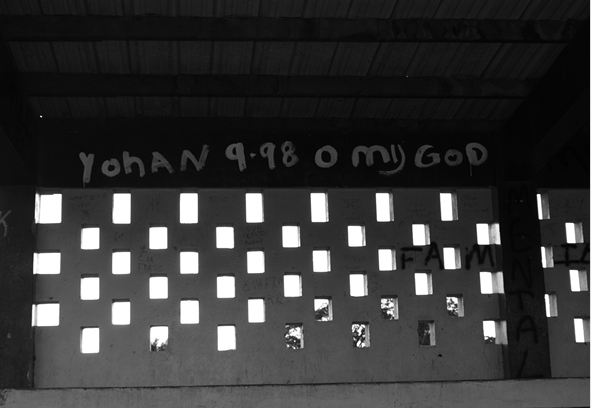

This happened for Yohan Blake, the current 100 metre world champion and holder of the second fastest time ever in the 200 metres. Blake attended St Jago High School – one of the schools which consistently performs well at the Champs. Apart from Yohan Blake, the school has hatched world stars such as Melanie Walker (Olympic gold medallist in the 400 metre hurdles) and Kerron Stewart (Olympic silver medallist in the 100 metres sprint). During my visit to Jamaica, head coach Danny Hawthorne showed me round St Jago High School. He pointed out the wall of the stands in the school’s athletic grounds. Somebody had written across it in white paint: ‘9.98 secs. Oh My God.’

The wall Yohan Blake painted with this goal

‘That was written by Yohan Blake when he was eighteen years old and training with me for Champs,’ Danny Hawthorne told me with a smile. ‘His great aim was to run under ten seconds and one year later he did it. He wrote it on the wall so that everybody could see it.’

‘If people want to understand what drives these girls and boys they must come to the Champs.’

Pure love of the game is not enough

Attempts to find out exactly what drives great performances have always revolved around looking at two factors: intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation. The question is, do top performers feel driven by their activity itself and the process of taking part in it, or are they driven by the rewards they can gain from it, such as prestige and money?

Most studies have concluded that the grit and persistence which characterise top performers stem from intrinsic factors. Pure passion and love are what have driven the world’s best to break records. How would anyone otherwise be able to push through the years of long, difficult hours of training necessary to become world class?

We love that explanation, just as we love the sappy, romantic ending of a sentimental movie. My conclusion from studying the six Gold Mines, however, is that intrinsic factors are far from adequate when it comes to explaining the hunger that drives top performers.

Just look at 43-year-old Esther Kiplagat, one of Kenya’s best female marathon runners. Throughout her childhood she trained extremely hard, running more than 100 kilometres a week. But after she retired in her late thirties she as good as stopped running. Today she doesn’t go jogging on the paths around Iten or spend time in the gym to stay in shape. She is now an overweight woman in her mid-forties, and her story is far from unique in Kenya. If Esther Kiplagat really loved running, why hasn’t she gone for a single jog since she retired?

Extrinsic factors play a far greater role than we are generally willing to admit. No matter how much we like to hear it, pure love of the sport is simply is not enough to carry you through to achieve world-class performance. The world’s best long-distance runners, tennis players, golfers, sprinters and footballers hunger for much more than the self-contained fascinations of their sport.

Think back to three-times world steeplechase champion Moses Kiptanui. He had a far greater passion for football than for athletics, but because he could earn more money and help his family by running, he started training like crazy. As Toby Tanser writes in More Fire: ‘The lure of prize money is powerful: a teacher in rural Kenya can make a salary of 4,000 shillings a year (approximately 580 dollars). The second finisher at a recent marathon in Huntsville, Alabama, won 750 US dollars in a time slower than the women’s marathon group in Iten clocks on their training routes.’

Today, even after so many triumphs, Moses Kiptanui watches football on television, not athletics. Money really does talk. The same applies to many of the Brazilian footballers. My research in the Brazilian football Gold Mine killed off once and for all the illusion of Brazilian boys dashing about on the beach at Copacabana with big smiles all over their faces. The truth is that the game is deadly serious. The appetite to do what it takes has been generated by the quest for social prestige, the promise of a bulging bank account and the feeling that they have an obligation to help their families out of poverty. It’s pure cash flow motivation. Thiago Mendez, director of the successful football academy Sendas Pão de Açúcar, told me: ‘If you give him 100 euros you can get a young Brazilian footballer to do anything you want.’

This is not the same as saying that Moses Kiptanui and the Brazilian footballers don’t love what they do. Inner passion does have a role to play, no doubt about it. I just do not believe that if we simply examine our hearts, the right path will reveal itself. This is one of the biggest misconceptions about motivation.

The traditional idea that an intrinsic source of passion fuels perseverance means that first you have to find out what you really burn for within. Apparently, once you have done that, self-discipline and persistence should emerge as a by-product. But while it is certainly true that extremely persistent people are usually passionate about what they do, this does not necessarily mean that the passion came first. As Angela Duckworth has emphasised in her studies of grit, perseverance can itself foster passion. It’s often the case that the most fascinating depths and nuances of the subject do not open themselves to us until we have really absorbed ourselves in our work and dedicated ourselves to the extent that we, as Duckworth says, ‘understand it and are enlivened by it’. In other words: first you must decide to persevere, and then passion will grow. Or as Moses Kiptanui puts it: ‘You learn to love what you do.’

For instance, in a study of 24 pianists, all of whom had been finalists in at least one significant international competition, psychologist Benjamin Bloom concluded that they had all been forced to pick up their instrument and practise early in their careers. None of them had spontaneously walked over to a piano and started playing. This does not mean that they had no passion. You will never become one of the world’s elite in your field without that, but their passion only fully emerged after they had been playing it for some time. They were deeply dependent on extrinsic factors to grow that passion.

My research in the Gold Mines showed that the passion it takes to become world class is not something that comes tumbling out of the sky. You have to work for it.

Train, sleep, eat … and do it again

Another mistake when it comes to motivation is the way that we frequently measure and judge it purely on the basis of how much effort a person puts in and how hard they work. We assume that if someone is really busy that they must be super-motivated. Hard work is certainly a good indicator of motivation, but it is not the whole story by any means. Having real drive is about much more than that. It also depends a great deal on what we do when we are not working; how we structure our lives around that long, hard slog. This occurred to me for the first time when I was in Iten, where I met one of the world’s best 1,500 metres runners, Augustine Choge, who broke the long-standing 4×1,500 metres relay world record with a Kenyan team in September 2009.

I watch him train, forcing his body to endure a succession of merciless interval runs. Afterwards we get into his big white Land Rover – the only outward sign of his success – and his drives me to his home. I’m a little nonplussed when we turn in to a grass field in front of two dilapidated shacks.

‘Is this where you live?’ I ask him.

He nods. By Western standards it looks more like a shed than a place anybody would want to live – and certainly not the world’s fastest 1,500 metres runner. The rusty hinges squeak as he opens the crooked wooden door and shows me in to his living room. There isn’t much in the way of furniture – an old massage couch and a sofa full of holes. An antiquated television set is chattering away on a table. The walls are papered with old newspapers. Behind the tiny living room is an even tinier double room with a bunk bed. This is where Augustine sleeps. But not alone, it transpires; he shares his accommodation with David Rudisha, the 800 metres world record holder.

I find it hard to believe what I see as I sit in the living room while Augustine boils water on his little gas cooker to make the Kenyan tea he drinks after every training session. This man has made good money from his sport. He could easily buy himself a fashionable flat in Nairobi. Nevertheless, he isolates himself in this little chicken shack in Iten all year round – apart from the few months when he is competing in Europe. These are, as he tells me, the optimum conditions for doing what it takes: sleep, train, eat, sleep, train, eat, again and again.

Such modest conditions are familiar to practically all Kenya’s top runners, who pursue a simple lifestyle during their preparations for major competitions. I hear on several occasions during my time in Iten how world-class athletes – who have already earned millions from their sport – leave their families for months at a time to isolate themselves under austere conditions prior to major events.

A world devoid of distractions

This is in stark contrast to the average Western lifestyle, where everything feels rushed. We celebrate fast reactions rather than considered reflection. We have to-do lists, smart phones, pop-up reminders on our computers and we are constantly sending and receiving emails and text messages. Starved of time we take pride in multitasking. Work never ends. This means that many people survive on far too little sleep – on average, children worldwide get one hour less sleep than they did 30 years ago. We lack focus and purpose, and feel constantly on the brink of burning out. As world-renowned performance psychologist Dr Jim Loehr explains, we find ourselves in a constant imbalance between expenditure of energy and renewal of that energy. This can have dramatic performance consequences – anything from a loss of passion, to increased likelihood of injury, to full-scale nervous breakdown. In their book The Power of Full Engagement, Jim Loehr and Tony Schwartz describe how energy, not time, is the fundamental currency of high performance. The number of hours is fixed, but the quantity and quality of energy available to us is not. The more responsibility we take for the energy we bring to a task, the more powerful and productive we become.

Let us return for a moment to Anders Ericsson’s ground-breaking studies of the violinists at the music academy in Berlin.

Apart from the fact that the best of them had practised much more than the next best, Ericsson discovered another crucial difference which distinguished the best violinists. They slept more. Not just at night; they also took a siesta after lunch. ‘The argument they gave,’ says Ericsson, ‘was that the real constraint on how much you could practise was not the number of hours in the day, but the number of hours in the day you could sustain full concentration. If you couldn’t sustain your concentration, you were wasting your time.’ The many hours they spent training were so mentally taxing that they needed to spend a lot of time revitalising themselves.

This brings us back to the point: motivation is not just a question of working harder at an ever-increasing rate. It is also about proper balance; deliberately investing time in energy renewal. You must not only train like a champ, you must sleep like one.

As triple steeplechase world champion Moses Kiptanui told me: ‘Recovery is as important as training. But not recovery in the sense most people understand it. If your brain is working while you are recovering, it means that you’re actually not recovering at all. Quality recovery is training.’

And Colm O’Connell was keen to stress: ‘Many people talk about training, but I speak to my athletes just as much about recovery.’

During my stay in Iten I frequently spoke to European runners and I kept hearing how they improved their standard every time they visited. Not because they trained harder or differently, but because they adopted the Kenyan lifestyle. Train, sleep and eat – nothing else! From the age of thirteen, Kenyans and Ethiopians live and train in a way that Westerners do only when they are on an intensive training camp. As the former half-marathon world champion Lornah Kiplagat says: ‘During the periods when I train hardest, I spend sixteen hours a day in bed. It is difficult to adopt this kind of lifestyle in the West, where there are far more distractions and stress factors. Mobile phones, television, and the internet are only a few of the things that can disrupt your focus. The ability to recover is underestimated as one of the explanations of the East Africans’ success. Our lifestyle facilitates quality recovery to a much higher degree.’

It’s actually pretty simple. Increase the demands you are making on yourself and it becomes necessary to recover your energy more effectively. Fail to do so and performance levels will fall dramatically. However, the problem is that in many environments, particularly businesses, the need for recovery is often seen as weakness, rather than an important prerequisite for sustained performance. Jim Loehr points out that: ‘We give almost no attention to renewing or expanding our energy individually or organisationally.’

Anybody who wants to make a major impact on their performance must, like the East African runners, understand that motivation is not just about doing more and pushing harder. It’s also about building routines for how to manage our energy more efficiently and intelligently. Otherwise we simply become flat-liners.

Man’s search for meaning

Any discussion of motivation is simultaneously completely universal and enormously personal. Universal, because ambition and passion are a must if you want to improve your performance, regardless of who you are and where you come from. Personal, because what creates and maintains ambition and passion for one person may not be what does for another. Because of this it is dangerous to start talking of the right or wrong motivation.

In 1946 the Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist Viktor Frankl published his book Man’s Search for Meaning, which has been hailed as one of the ten most influential books ever written. Frankl spent three years in concentration camps during World War II, including Theresienstadt, Auschwitz and Dachau. It was during this period that he formulated many of his key ideas. His book gives a first-hand account of his experiences during the Holocaust, and describes the psychotherapeutic method he pioneered, Logotherapy, which is founded on the belief that striving to find meaning in life is the most powerful motivation for human beings. Frankl’s mother, father, brother and pregnant wife perished in the concentration camps. He lost everything that could be taken from a person, apart from one thing: ‘the last of the human freedoms, to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way’. Frankl describes how some of the prisoners at Auschwitz were able to find meaning in their lives, for example by helping each other through the day. Small meaningful moments gave them the strength and the will to endure.

Frankl himself found meaning by helping his fellow prisoners hold on to their psychological health. As he writes: ‘We had to learn for ourselves, and furthermore we had to teach the despairing men, that it did not matter what we expected from life, but rather what life expected from us. We needed to stop asking about the meaning of life but instead to think of ourselves as those who were being questioned by life, daily and hourly.’

Frankl’s ideas have since been taken up and built on by scientists the world over. Many of them have attempted, for example, to test the importance of meaning in the business world, and the results are crystal clear: people are willing to perform the most menial of tasks, even for low pay, as long as they consider the work to be meaningful or are recognised for their contribution.

In his study ‘Man’s search for meaning: the case of Legos’, Duke University Professor Dan Ariely set out to understand how ‘perceived meaning’ affects a person’s motivation and willingness to work. Ariely asked two groups of people to build Lego models. The Lego models built by one group of participants were left on the table in front of them so that they could enjoy the results of their work and the supervisor would give them a new box of Lego bricks to build more toys. Hence, as the session progressed, the completed Lego toys would accumulate on the desk. The work they did had enduring results which gave the task meaning.

By contrast, each model made by the other group was removed from the table as soon as it was completed. The supervisor would then take the models apart and put the bricks back into the box. The models made by this group were not allowed to accumulate; members of the group were constantly reusing the same bricks. Their work had no enduring results and so in a sense their task was meaningless.

There was no other difference between the conditions of the two groups.

Surprisingly, the average number of models a person was willing to build significantly differed between the two groups. Although the physical requirements of the task were identical for the two groups, the subjects whose models were preserved built 30 per cent more Lego toys than those in the setup in which the meaning of their work had been taken away.

As Ariely concluded: ‘These experiments clearly demonstrate what many of us have known intuitively for some time. Doing meaningful work is rewarding in itself, and we are willing to do more work for less pay when we feel our work has some sort of purpose, no matter how small.’

How can you possibly beat Shelly-Ann Fraser?

This constant search for significance in what we do is crucial to all of us, whether we are top athletes, managers, musicians or parents. As the American author Malcolm Gladwell writes: ‘Hard work without meaning is a prison.’

The problem in the business world is that often the end-purpose of a company has been broken down into so many disparate tasks that workers feel very little connection with that end result, and as a consequence feel very little motivation. Dan Ariely advises managers to find ways in which they can add more meaning to even the simplest and most routine job functions: ‘It’s a question of educating employees about the goals of their work, and the way individual tasks fit into the bigger picture, as one way of overcoming perceived lack of meaning in work.’

It’s important for a company to fire an enthusiasm for what it does externally as well as internally. A vital aspect of any CEO’s job is communicating a company’s raison d’être in such a way as to ensure that people relevant to the business feel engaged and enthused. Communicating that a company has a deeper purpose than simply making as much money as possible is vital.

Let us take Lego as an example. The company basically just makes plastic bricks, but there is far more to it than that. When children play with Lego bricks they train the right (creative) and left (logical) sides of their brain simultaneously. In other words, they are involved in systematic creativity. Thus Lego could argue that they are helping to train and inspire tomorrow’s problem-solvers. Think about it: which company do you think people would prefer to go the extra mile for? One that makes plastic bricks or the one that trains tomorrow’s problem-solvers? The answer is easy.

Giving a clear message about the meaning of a company also helps to attract the best possible workforce. Talent flocks to organisations that project a strong sense of purpose. The opposite is also true – capable people flee from places where their jobs feel purposeless or where their objectives do not feel genuine. If an organisation’s underlying meaning is powerful enough you can be sure that people will grab the opportunity to contribute, even if their job involves challenging or monotonous tasks. The power of meaning to motivate us applies in our private lives as well. Just see what happens when people have children: they suddenly have a lifelong source of meaning for which they will fight and do anything.

It is the same for elite athletes. They must be capable of finding and sustaining a powerful sense of meaning in what they do if they are to be among the best. The key to lasting high performance in any field is to find a compelling mission, one for which you are willing to suffer a lot of lactic acid.

This brings us back to Shelly-Ann Fraser. There is no doubt that she has found meaning in what she does. And how can you beat a opponent who knows that her victories save lives in the neighbourhood where she grew up? For Shelly-Ann Fraser a race is not just a question of putting one foot in front of the other and running 100 metres as fast as possible. It involves much more than that.

The same applies to many of the Brazilian footballers. In 2009 a group of students from Nyköping in Sweden went to Brazil to study what drives the nation’s footballers. They quizzed players between the ages of thirteen and nineteen at some of the biggest clubs across the country, asking why they played football. They asked the same question of players the same age in Sweden.

Almost without exception, the Brazilians replied that they played to earn money to help their families. In comparison, Swedish boys didn’t mention their families. They just wanted to be famous.

It is not difficult to guess which of these motivating forces is the stronger. For Brazilians it’s not just about football. It’s about creating a better life for your nearest and dearest.

In Bekoji, too, people have an overwhelming sense of purpose. As Sentayehu Eshetu, a self-made coach explained to me: ‘If you want to understand the secret of Bekoji, you must understand that kids here have nothing. They are willing to do anything to succeed.’

The West is spoiled by choice. You want to be a filmmaker? Take a class. Got no money? Apply for a grant. In Bekoji there are no reality television shows or line-up auditions. Rural East Africans have to be thinking constantly about how they will survive; how they will carve out a life for themselves. Standing still does not pay. The surest way to succeed is to keep putting one foot in front of the other, and Ethiopians excel at this.

Hunger in paradise

When I deliver lectures on high performance to companies and organisations in the West, I often ask the audience the question: ‘How can you create hunger in paradise?’

Most of us live very comfortable lives where we really don’t need to put ourselves on the line to ensure our quality of life. This is not an environment that creates top performances.

When everything is going to plan and running smoothly, it is only natural to feel the flow; to feel motivated. But when the going gets tough it is important to have a hoard of good reasons to get out there and do it anyway. Are you hungry enough to maintain your momentum at times when you least feel like making the effort? This is the paradox of motivation. The greatest payback often comes when you least want to carry on, and it is almost certainly easier to convince yourself that it is worth continuing if you are running for the sake of your family than if you are only running for yourself.

A good example, which we have already mentioned in this book, is the British Lawn Tennis Association, which receives millions of pounds to develop world stars, but which consistently fails to do so. If the British LTA really wanted to produce great players, my advice would be to pull down the state-of-the art modern facilities they own and instead build public tennis courts in Brixton, one of the poorer London boroughs. If they dished out free tennis rackets and offered free qualified coaching to all interested children and young people, in ten years I promise they would get the top tennis players they have been hankering after for so long.

How to create hunger in paradise will be the billion-dollar question in years to come and I don’t have the answer myself. But I do know that even the most spectacular training centre cannot beat a meaningful, burning desire to succeed.

In the end there is only one thing that counts: who wants it most?

What you should never forget about

MOTIVATION

1. Nothing beats a really burning desire. It’s without doubt the single most important predictor for world-class performance.

2. Why is the most powerful psychological question to boost motivation. Much more important than what. Any individual or organisation must ask themselves why they do what they do, and what would happen if they didn’t.

3. Don’t wait for the thunderbolt of passion to hit you. It’s not going to happen on its own. Instead, start to act – engage and invest yourself in what you do and the passion will start to flow. Often it’s perseverance that fosters passion, not the other way around.

4. Motivation is not just about doing more and pushing harder. It’s also about building routines for how to manage our energy more efficiently and intelligently. It’s a commitment to a lifestyle where you not only train as a champion, but also recover as a champion.

5. The form motivation that brings a person or an organisation to one goal will not necessarily bring them to their next. Often motivation has to be reignited, visions must be renewed and meaning deepened in order to to maintain momentum.