What you see is not what you get

‘It isn’t difficult to identify talent like Usain Bolt. Anybody could see that he had huge potential when he was sixteen. The real challenge is to identify the potential in something currently ordinary that hasn’t flourished yet.’

Stephen Francis, head coach of the MVP Track and Field Club

Many people were amazed when, on a June day in 2005, at the Athens Olympic Stadium, the 22-year-old Jamaican Asafa Powell sprinted his way into the history books, setting a new world record in the 100 metres. The surprise was not so much that Tim Montgomery’s world record of 9.78 seconds had finally fallen, but that it was a virtual unknown who toppled it. Unlike his countryman, Usain Bolt – who already as a thirteen year old was predicted to set new standards in the sprint distances – nobody expected very much at all of Asafa Powell.

Only three years earlier, Asafa was just another Jamaican teenager wandering about Kingston trying to find a place to train. His best time for the hundred metres was 10.8 seconds, which he ran in a semi-final during his high school’s championships. This was not nearly fast enough for somebody to want to invest in his future. So how could an unknown Jamaican develop in just a few years from a mediocre sprinter to the fastest man on the planet?

It would soon transpire that Asafa Powell’s world record was the first symptom of the sprint revolution that was seething just below the surface of global athletics. It broke out in full three years later at the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Here, the Jamaican sprinters annihilated the competition, winning an unheard of eleven medals (six gold, three silver and two bronze). They set three world records and four Olympic records. When Shelly-Ann Fraser, Veronica Campbell-Brown and Sherone Simpson took the gold, silver and bronze in the women’s 100 metres, the demonstration of power was complete. The world was incredulous and its gaze was fixed firmly on one tiny island in the Atlantic.

Unknown world stars

It is old news that the Jamaicans regularly show up among the world’s fastest sprinters. Over the last 50 years, they have regularly received medals in the sprint distances at major championships. And at the fifteen Olympic games held during the period 1948–2004, Jamaica won an average of a little under three medals per games, which is not bad at all for a nation of only 2.4 million people. In this light, the medals in Beijing shine even brighter. They show an almost 400 per cent improvement in performance over four years. But was this just a one-hit wonder?

Twelve months later, at the 2009 World Championships in Berlin, Jamaica proved beyond doubt that it was not. Again, the Jamaicans outperformed the rest of the world’s athletes, and with even greater superiority than in Beijing the previous year. A total of thirteen medals (seven gold, four silver and two bronze) crowned the Jamaicans the undisputed kings (and queens) of sprint. If the world was incredulous after the Beijing Olympics, now they were completely stupified. Even the United States, traditionally the major sprinting nation, was left in the dust by this display of Jamaican reggae power. The sprint revolution was now a reality and if there was one question the championships in Berlin begged, it was this: how had Jamaica developed in just a few years from being merely a decent sprinting nation to the world’s undisputed ruler?

The yam effect

No end of people have tried to explain Jamaica’s turbo-charged magic. One of the more entertaining explanations is referred to as the ‘the yam effect’. After Usain Bolt’s win in the 100 metres at the Beijing Olympics, his father, Wellesley, told reporters that the secret to his son’s success was the potato-like vegetable, the yam. More specifically, the yellow yam, which is said to be the favourite yam in Jamaica and which is apparently Bolt junior’s favourite food.

Others have attempted to attribute the Jamaican’s success to their shared history as slaves more than 175 years ago. This, the theory goes, gave them the aggressiveness, ferocity and strength it takes to run like human cheetahs.

A third explanation, as naive as the yam-effect, is that the Jamaicans have long ring fingers – this, in some way or other, is supposed to help them to run faster.

These increasingly implausible theories simply reflect the world’s astonishment at the seemingly equally implausible results Jamaica’s sprinters have delivered. But it does not end there. Their achievements become even more impressive when one realises that the stories of many Jamaican athletes are similar to that of Asafa Powell.

Take the world champion and Olympic champion in the 100 metres for women, Shelly-Ann Fraser; or the Olympic silver medallist in the 100 metres, Sherone Simpson; or the world champion in the 110 metres hurdles, Brigitte Foster-Hylton. Until a few years ago, they were all athletes who had been written off because they had not made the grade.

Jamaica’s demonstration of power is not about a long string of superb talents finally showing their worth. It is about unknown sprinters suddenly breaking out as world stars. And so I set off to explore the enclaves of Jamaican sprinting. My purpose was to solve the mystery of this tiny nation turning completely overlooked sprinters – considered to be grade C or D at best – into Olympic winners and world champions in just a few years.

We are going to beat the American high school coaches

One September day in 1999, nearly ten years before the Jamaican blitzkrieg in Beijing, two men, Bruce James and Stephen Francis, were sitting in a flat in Kingston reaching a decision that would come to shake the entire athletics world. The two went way back – as a high school athlete, James had been coached at Wolmer’s Boys’ School by Francis, who was only four years his senior. Together they improved James’s time in the 400 metres enough for him to win a track scholarship to Florida State University in the United States. Francis also went to the US, where he took an MBA in finance at the University of Michigan. He planned to use it as a springboard into the corporate world, and when he came back to Jamaica he joined the international firm KPMG. But he missed athletics. His great passion for coaching was tugging at him. He began to think about returning to the world of athletics, and to speculate about the possibility of doing something very special there.

Strange as it may seem, Francis was never an athlete himself – he arrived at his expertise through reading. To begin with he spend a lot of time at the library in Kingston and then, as he began to earn more money, he started buying and importing books on the subject of coaching and improving athletic performance.

After a few months of consideration, Stephen Francis decided to resign from his job in order to coach full time. That is how he came to be sitting there with his old friend Bruce James, planning what we know today as the biggest sprint revolution of the last 50 years. The basis of this revolution was simple – Francis and James wondered why Jamaican athletes always had to go to the United States in order to succeed. Why not train them at home in Jamaica?

The general conviction was that Jamaican high school coaches were nowhere near as good as American coaches. When it came to athletics, the Jamaicans were simply babysitters for the Americans – when the best Jamaican athletes left high school, these sublime American coaches would take over and transform them from merely good athletes into extraordinary athletes. There was plenty of evidence that this model worked. As far as everyone was concerned, the way forward was via the US. This had been the case for Olympic medallists like Grace Jackson, Merlene Ottey, Don Quarrie and many others. All had been given a scholarship to an American university and subsequently won medals at the World Championships and the Olympics. These examples seemed to emphasise that the system worked – and if the system isn’t broken, then why fix it?

But Bruce James and Stephen Francis were convinced that there was a better way. Francis had a tremendous record of training young Jamaican athletes to the standard required to get a scholarship to the US, but he felt as though they never really realised their full potential once they got there. He expected to see them at the World Championships and the Olympics, but it never happened. In fact, he had never been particularly impressed by what the American coaches achieved with Jamaican athletes. Given this he began to consider the possibility of creating a new training environment on Jamaica – one that would pump out superstars.

So on that September day in 1999 James and Francis decided to found the MVP (Maximising Velocity and Power) Track and Field Club. James became president and Francis head coach. Together they launched the project with the words: ‘Gentlemen, we shall show the American college coaches that we can do the job ourselves here in Jamaica.’

Barefoot sprinters

The MVP Track and Field Club was a project founded against all odds. People in Jamaica shook their heads at the level of its ambition. Francis and James were called unrealistic dreamers. It was also almost impossible for them to attract the best, most talented sprinters. Not only did training take place on a diesel-scorched grass field; they couldn’t even afford to buy running shoes for their athletes. As a result, many of them trained in bare feet. Added to this was the fact that Francis, the head coach, had never been an elite sprinter himself and had only coached youth athletes. They quite simply had no results to show.

So rather than working with the top athletes in Jamaica, they had to make do with those who were willing to train with them, and the only people willing to stay in Jamaica to train were those who the Americans had turned away. Francis began to look for young sprinters who were good enough in his eyes but who had not been deemed good enough for a scholarship to the United States.

The first athlete at the MVP Track and Field Club was a 25-year-old Jamaican woman. Although she had been to university in the United States, she had never quite had a breakthrough and had now returned home. She was the perfect candidate. Her name was Brigitte Foster-Hylton.

Brigitte Foster-Hylton training on the grass tracks at the MVP Track and Field Club in Kingston

Just a year later, under the guidance of Stephen Francis, her performance had improved so much that she managed to qualify for the 100 metres hurdles at the Sydney Olympics, where she crossed the line in eighth place.

James and Francis were ecstatic. They had taken an athlete who had been written off and trained her to become one of the best in the world. They felt they had made their decisive breakthrough. In actual fact, nobody seemed to take much notice of the story of Brigitte Foster-Hylton. At the same time, the MVP Track and Field Club was seriously low on funds. Francis was forced to sell his car and was in such a poor financial state that he was unable to get a credit card. He couldn’t afford even electricity because he needed all his spare money to make sure that his athletes didn’t starve; many of them couldn’t afford to buy their own food. Despite the inspirational story of Brigitte Foster-Hylton, the MVP was on the verge of collapse.

In late 2000 Stephen Francis heard about the 19-year-old Asafa Powell through a friend. As we saw earlier in the chapter, Powell’s results were far from impressive – his best was 10.8 seconds in the semi-final of the High School Championships. Moreover, he came from a school that nobody in Jamaica knew, and which did not have a well-developed athletics programme. But Stephen Francis recognised his potential. He thought if he could get the lad to train in a structured manner, he could probably get him to go a long way. Within a week of Stephen Francis seeing him run, Asafa Powell was standing on the MVP training track.

Somehow, the MVP Track and Field Club scraped along until 14 June 2005. It was then that the breakthrough came. At the Olympic stadium in Athens, Asafa Powell crossed the line in 9.77 seconds (a new world record), and so became the fastest man on earth. How could almost everyone, the Americans included, have overlooked Powell’s potential? How come only Stephen Francis could see it?

The MVP effect

Asafa’s world record was precisely what the MVP Track and Field Club needed and since that day they have never looked back. At the Beijing Olympics, MVP’s eight athletes brought home nine medals, five of them gold, setting one world record and one Olympic record along the way. They repeated the trick at the World Championships in Berlin – Francis’s eight sprinters, in an out-of-this-world demonstration of power, won eleven medals, six of them gold. One of those gold winners was the MVP’s first athlete, Brigitte Foster-Hylton. This total domination has since become known as the MVP Effect.

Today, the MVP Track and Field Club is the indisputably the world’s most successful athletics club, and is the reason that Jamaica leads the world in the sprint distances. Stephen Francis and Bruce James are the architects of this sprint revolution. Remove the MVP athletes’ performances from the equation and Jamaica performs precisely as it always has done. Only two of the eleven medals the country won at the Beijing Olympics were won by non-MVP runners.

In other words, to understand the secret behind the Jamaican super-sprinters you have to understand how Stephen Francis thinks. The success of the MVP athletes has nothing to do with genes, yams or traits arising from suffering the atrocities of slavery. We must realise that first and foremost it can be traced back to Francis’s ability to spot potential in a sprinter that everyone else overlooks. When it comes to spotting talent, he has totally changed the game, rethinking all the traditional methods and assumptions.

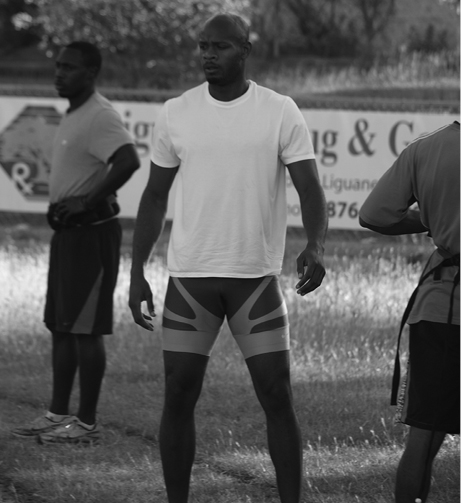

Asafa Powell at the MVP Track and Field Club’s training ground

Stay clear of ‘can’t miss’ athletes

It is 5.30 in the morning and I am standing in front of the MVP Track and Field’s training ground in Kingston. The smooth contours of some runners moving silently through the dark are just visible behind the fence. I can see about 40 athletes on the grass, once my eyes have accustomed themselves to the dark.

The silence is suddenly broken by a big black BMW which drives at speed towards the fence and stops just behind me. A large, round man dressed in a loose T-shirt gets out. With slow, short steps he moves his wide body towards the hole in the fence that is the official entrance to the training ground. This is Stephen Francis. ‘Welcome to MVP,’ he says, offering his large hand.

Like everything else on the training ground, Stephen Francis does not resemble what he actually is; his BMW is the only obvious sign of his success. He simply arrives here every morning at 5.30, sets up his folding chair on the grass and proceeds to oversee the training of the world’s best sprinters in his deep, booming voice.

Stephen Francis

Stephen Francis, head coach of the MVP Track and Field Club

is a man of few, though meaningful, words. He answers when you ask a question, otherwise he says nothing. At home in Jamaica he divides opinion. Some call him a genius; others call him greedy and arrogant. But nobody can deny the list of super-athletes he has created, which makes him the world’s most successful sprint coach. And one of the most thought-provoking things about Francis is the fact that he has never sprinted himself, but trained as a statistician. He sees this as an advantage. In his words: ‘I think that I have an extra perspective as a coach because I have not been active myself. Many athletics coaches are themselves former athletes. I have taken the steps to understand what they know, but I don’t believe that they have taken the steps to understand what I know.’

And we should keep in mind not only the incredible results of the MVP Track and Field Club but also the story of previous mediocrity which so many of its athletes share. Nobody was a star before they came here. Many of them had not even won a medal in the Jamaican High School Championships. Olympic medallists like Shelly-Ann Fraser, Sherone Simpson, Shericka Williams and, by no means least, the former world record holder in the 100 metres, Asafa Powell. All of them were unknown athletes with no real hope of a successful career, until they came under Stephen Francis’s wing.

Sherone Simpson and Shelly-Ann Fraser after training at MVP

‘I love to work with people who are hungry for a second chance. I love to prove that people made a mistake. That other stuff bores me,’ he tells me, before blowing loudly on his whistle, at which his athletes jog in small groups towards where he sits planted on his folding chair. The sun has just come out and Francis has donned his sunglasses. Moments later the athletes are crowding around him. I quickly spot three Olympic gold winners amid the throng.

‘I stay clear of those I call “can’t miss” athletes as a matter of principle. Instead I look for those with the greatest development potential,’ Francis finishes.

Talent that whispers

In his excellent book The Rare Find, the business journalist George Anders distinguishes between two types of talent: that which shouts and that which whispers. Usain Bolt is a perfect example of talent that shouts – what Stephen Francis calls a ‘can’t miss’ athlete.

At the age of fifteen Bolt was the youngest junior champion ever. He performed outstandingly, and obviously possessed tremendous potential.

‘Athletes like Usain Bolt [100m and 200m World Record Holder] and Veronica Campbell-Brown [Olympic 200 metres champion] were also the very best when they were juniors. The fact that they run very fast isn’t news. You would have to be half blind not to recognise their class,’ Francis explains to me.

Asafa Powell, on the other hand, is a perfect example of talent that whispers, and the same applies to Shelly-Ann Fraser, Brigitte Foster-Hylton, Sherone Simpson and Shericka Williams. All of them possessed tremendous potential but went unnoticed because this was not obviously apparent in their performance at the time.

Talent that whispers is found in all walks of life, and is far more common than we might believe. Take, for example, the two FC Barcelona star players, Andres Iniesta and Xavi, who helped win the World Cup for Spain and brought the Champions League Trophy and the Spanish championships home to Barcelona. When they were on the youth team aged twelve and fourteen they won nothing, and as eighteen and nineteen year olds they had lost more matches than they had won.

And the best basketball player of all time, Michael Jordan, was not deemed good enough to play on his high school team at the age of sixteen.

The former world 800 metres champion and world record holder Wilson Kipketer was nowhere near the best athlete at the boarding school he attended in Kenya.

And perhaps the best example of all is the Brazilian football legend Ronaldo Luíz Nazario de Lima. In 1996 he walked onto the stage to receive his FIFA World Player of the Year award at the a gala dinner in Zürich. Bathed in the flashlights of the world media, the nineteen-year-old Brazilian received the Golden Ball as the youngest player ever to do so, following an outstanding season at FC Barcelona. His performance led football experts to compare him with legends like Diego Maradona and his fellow Brazilian Pelé.

However, nobody could have imagined Ronaldo’s success in their wildest dreams if they had seen his circumstances just four years earlier. He had been drifting clubless around Brazil looking for a contract. Flamengo turned the fifteen-year-old Ronaldo away at the door because they were not sufficiently interested to be willing to pay for his bus fare to and from training (about a dollar for a return ticket). The reason they gave was that he was too small and slight. He was subsequently rejected by several other Brazilian clubs for the same reason, until he was finally accepted at Cruzeiro in the city of Belo Horizonte, some 500 km from Rio de Janeiro.

In fact, more or less the same script seems to have been played out in the lives of some of the most successful individuals, and not just in sport but in areas ranging from investing and politics to publishing, music and advertising. Many of today’s biggest stars in those fields were hardly noticed at first. One of the most outstanding examples is J.K. Rowling, author of the Harry Potter series, which has sold more than 450 million copies worldwide. She was rejected time after time by publishers until Bloomsbury eventually took a chance on her – and you can bet they’re glad that they did! Paul Cézanne, Elvis Presley, Michael Jordan, Ray Charles and Charles Darwin were all thought to have little potential in their chosen fields. In other words: the world has many ‘Asafa Powells’ in it.

How to spot a superstar

In retrospect we laugh at the football coaches who refused to pay Ronaldo’s bus ticket and the college coaches who repeatedly rejected Asafa Powell. How could anyone reject point-blank a player who four years later would be voted the world’s best? How can you overlook the potential of one of the fastest people on earth? What a blooper. But were they foolish or incompetent, or is trying to predict future accomplishments just mission impossible?

Probably the coaches were right about Ronaldo and Asafa – in terms of their skills at the time. They were not yet performing at even close to the level which would one day make them famous. After all, there was a time when Asafa Powell was just an ordinary guy.

And that’s just the point: how do you spot the potential in something that looks ordinary? Fundamentally, it is a prediction problem. What does potential which has not yet found expression look like? And what do we look for when potential does not manifest itself in current top performance?

Figuring out how to catch those early stirrings of promise is quite rightly an obsession for any ambitious organisation, whether it’s an advertising agency, a baseball team or a music academy. They all want to win the war for talent, and nobody wants to walk past the next superstar. But how do you spot a superstar who is not yet a superstar? What does talent that whispers look like?

What you see is not always what you get

The answer to those questions is worth a lot of money. All over the world, in every field from academia to music, millions of dollars and thousands of hours are being spent on identifying high-potential performers early on. The harsh truth, however, is that the vast majority of these talent-ID programmes use ineffective methods. In many cases they are no better than drawing lots. As Capital One’s CEO, Richard Fairbank, put it several years ago, ‘At most companies, people spend 2 per cent of their time recruiting and 75 per cent managing their recruiting mistakes.’

Take the NFL (the National Football League in America), for example, the crème de la crème of talent identification science.

The NFL Scouting Combine is held in April every year. It is a sort of mini-camp where NFL coaches and managers meet to assess the nation’s greatest talent. In simple terms, the idea is to invite North America’s 300 best college players to Indianapolis where they are then tested in every aspect of the game – how high they can jump, how much weight they can lift, how fast they can run and so on. All these tests are designed to produce an accurate picture of the players’ true potential, and every bit of available data is analysed. The whole thing is transmitted live on American TV. Millions of dollars are at stake, meaning that managers and coaches demand extremely reliable information – they need it in order to have the best chance of correctly predicting the stars of the future. This is what the NFL Scouting Combine is all about.

But there’s a problem: every year, the NFL coaches and scouts manage to get it absolutely wrong. In fact, out of the 40 top-rated combine performers over the past four years, only half are still in the league.

A good example of how ineffective the techniques used by the NFL can be is the famous Wonderlic Cognitive Ability Test, which is used by the NFL Scouting Combine to test potential quarterbacks. To be a quarterback in the NFL you have two possess well-developed cognitive skills and be a quick, confident decision-maker. You have to be able to remember thousands of game situations, and you have to spend hundreds of hours studying attack openings and strategies. It seems to make good sense to apply an intelligence test to candidates, but it turns out that among the seven players noted for the worst performances in the Wonderlic test in the history of the NFL Scouting Combine, we find two of the best quarterbacks ever – Terry Bradshaw and Dan Marino. In other words, the test appears to be useless as an indicator of potential as a quarterback, to put it mildly.

So it seems to be exceptionally difficult to spot superstars, and we can find frustrated talent assessors in practically any field. It is not just in the sporting world that money is routinely wagered on draft picks that end up being hugely disappointing. Many corporations spend millions attracting new hotshot executives, only to end up writing even larger severance cheques a few years later in order to get rid of their failures. And think about the entertainment industry – sales bins are bursting with merchandise, CDs and movies which were supposed to have attracted millions of fans but which never made their mark.

The art of identifying the extraordinary – talent that will consistently drive exceptional productivity and give lasting results – is an extremely tough discipline. In desperation at the many poor guesses made during the last decade, we have made talent identification more sophisticated and complex than ever before. We have huge job databases at our disposal. Specialist software allows us to sort and prioritise skills in an instant, and as if that were not enough, we can also choose between numerous psychological tests which are supposed to tell us about candidates’ reaction patterns, personalities and chances of success. But despite the availability of all these technical aids, there is little indication that we have improved in any way when it comes to identifying potential. It seems to remain an unsolvable mystery.

Back in Kingston, Jamaica, Stephen Francis is laughing into his beard. His track record bears witness to an uncanny skill to see potential that nobody else can. It is interesting to consider whether Stephen Francis would be better at spotting a software engineer than many software companies. Whether he would be better at spotting the potential of teachers than most schools. Whatever the field, everyone basically wants to achieve the same thing: to find the superstars before anybody else does.

Step back from the details of Stephen Francis’ methods, and it’s possible to discern a few big ideas that can apply almost anywhere. Here are the four principles to spot talent that whispers.

1. It’s not about the performance – it’s about the story behind the performance

When we try to spot up-and-coming superstars, it is not that the methods we typically use are poor at assessing the things they are meant to assess. The problem is that measuring people’s performance is the wrong way to approach the task, and it’s especially likely to overlook talent that whispers. If you want to assess whether a person has what it takes to be among the world’s elite in their field, it is no good looking at what we can see here and now: current performance. To spot real potential you must be able to look beyond that and identify the complex, multi-faceted qualities that help someone learn and keep on learning, to break barriers and to work beyond inevitable plateaus.

Imagine an iceberg.

Icebergs float on the ocean with only about 10 per cent of their mass visible above the surface; the remaining 90 per cent is concealed beneath the waves. Think of the upper 10 per cent of the iceberg as current performance. The 90 per cent beneath the water is the currently unseen potential. It is there that the answers lie – in the mindset, the motivations and the values that form the basis of the current performance you are witnessing. That means that you will also find the seeds of development potential there. None of this can be measured with a stopwatch or a tape measure. It’s far more subtle and complex, and requires that you do not allow yourself to be distracted by current performance. It is precisely this skill which Stephen Francis possesses in such abundance, and which has been the basis of the sprint revolution at the MVP Track and Field Club.

According to Stephen Francis, one of the great misconceptions about talent identification arises from our conviction that current high performance automatically equals a great potential and that current average performance equals low potential. Current performance can certainly be a good indicator of potential but this is not always the case.

One way to understand the difference between performance and potential is to look at them in isolation, using a classic nine-box matrix like the one below. The X (horizontal) axis assesses current performance – the results the person delivers here and now – and the Y (vertical) axis assesses potential – a prediction of future talent, possible achievements and capabilities. By combining their places on the X and Y axes we can locate an individual in a particular box on the grid.

Let us return for a moment to the phenomenal Usain Bolt, who is one of those athletes who was spectacular even in childhood. He’s been winning competitions his entire live, and still does. In our matrix, athletes like him are characterised as high performance/high potential. Asafa Powell, on the other hand, demonstrated nothing extraordinary in his early performances, even when he first started training at MVP. He would be placed in the average performance/high potential box. Spotting the potential of someone like Asafa is much more difficult – you have to look beyond your initial snap judgement of the person.

This is precisely why Stephen Francis’s methods concentrate on people’s potential to rise beyond what they have done to date and not only on their current performance. What is important to him is not performance in itself, but what caused it and the story that lies behind it. Because of this, one of the key areas Francis looks at when trying to assess talent is training history. This is based on the idea that if you know an athlete’s past, you’ll have a greater chance of evaluating the possibilities for future. As Francis explains: ‘Imagine that you see a guy running the hundred metres in 10.2 seconds as a nineteen year old. Then you see another nineteen year old running the distance in 10.6. Everything seems to be screaming at you that you should choose the one who runs 10.2. But if you’re good, you will know that the guy who ran the distance in 10.6 may have even greater potential. Imagine, for instance, that the 10.2 guy is came from a very professional and qualified training environment, while the 10.6 guy basically trained on his own. I look very closely at athletes’ training histories. The better an athlete is without having a good training history, the greater the potential that exists.’

The exact same principle applies in fields other than sport. Lots of factors can influence the performance level of a business team as well as for an individual. Luck is one of them. Although sustained high performance may arise from skilful management or other valuable, rare and intimitable qualities, it can also be product of luck. Among other factors affecting results are unique circumstances, conjunctures, available resources and so on. If you deeply understand what role these factors have played in achieving a given result, you’ll have a much more solid knowledge on which to base your judgements about the real potential of a team or individual. If you really take the time to understand the story driving the numbers in front of you, you’ll suddenly start seeing the patterns that will allow you to find undervalued talent both inside and outside an organisation. This is what characterises every outstanding leader, whether they are a coach, entrepreneur or teacher.

This approach is how Stephen Francis found Asafa Powell, who at the age of seventeen ran the 100m in 10.8 seconds. He’d been to a poor high school with a bad coach and hadn’t trained much at all. The training he had done consisted of him going over to G.C. Foster College in Kingston, looking at the way they trained, then going home and doing the same thing.

‘This told me that Asafa probably had considerable underexploited potential,’ Francis explains.

Talent apartheid

We can find one of the worst examples of staring blindly at performance and overlooking the story behind in football. An interesting pattern will appear before your eyes if you spend an evening studying the 300 players who were selected for the 2010 FIFA World Cup. 32.4 per cent of the players were born in January, February or March. 25.2 per cent of the players were born in April, May or June. Only 21.5 per cent were born in July, August or September and 21 per cent in October, November or December. In other words, the World Cup is a big party for boys born early in the year. In disciplines like ice hockey and tennis, this pattern also flourishes. The figures speak for themselves, but what lies at the roots of this strange trend?

The explanation is simple. To understand the reasons for the pattern we have to go back in time to the point where these players were identified as talented, to the moment the coach said: ‘I believe in you. You have talent, and for that reason you will have a special chance to realise it.’

This moment usually occurs for young footballers between the ages of eleven and fifteen. By this point they have been divided into year groups; they play together with children who were born in the same year. Now, try for a moment to think back to the class you were in at school when you were fourteen years old, or perhaps a sports team you played on. What were you like? Were you big and strong, or were you small and slight? Were you an early or late developer compared to others the same age?

My guess is that in retrospect you will remember prominent cognitive, physical and emotional differences between the oldest and the youngest fourteen year old. A rule of thumb is that there can be as much as three years’ developmental difference between children born in the space of one year, if you look at them during adolescence. In other words, an early-developing eleven year old might be at the same level of physical maturity as an average fourteen year old, but so might a late-developing seventeen year old.

Imagine what this difference means to current performance in a physical sport like football. Who do you think will be most dominant on the pitch? And who do you think most coaches will notice? The answer is obvious. The phenomenon has been dubbed ‘relative age’ and is the reason that players born in January, February and March are consistently over-represented in the world’s football teams. People assume they are spotting talent, while in actual fact what they spot is physical superiority due to early development. In other words: what you see is not always what you get. Any parent, coach or teacher should be aware that just one single judgement that focuses solely on current performance without an understanding of the underlying reasons for that performance can have dramatic consequences for someone’s future path and potential.

Let us return for a moment to the nine-box matrix. Many footballers born early in the year, who as a result are more likely to develop early, can be categorised in the top left-hand corner: high performance/low potential. They are good right now, but this often doesn’t indicate great potential, instead being due to temporary physiological advantage. I call this phenomenon ‘high performance blindness’. Most of the people entrusted with the task of spotting and developing talent are part of a totally colour-blind talent sect. They are only able to see a current, black-and-white snapshot of a player. Are they good, or not?

There is absolutely nothing wrong with a process of selection and rejection. That is in the nature of talent development. The problem is that when we are looking at children and young people, selection discriminates against more than 50 per cent of the talent mass. This is modern talent apartheid. Players born during the first few months of the year are often given opportunities that they have neither worked hard for nor deserve. They don’t just get the best coaches and the best coaching; they also get more training, and self-confidence derived from the feeling that people believe in them. All this can give their motivation a powerful shove, making them more likely to put in the hours of training necessary to become really good.

No organisation and no country can afford to waste more than half the talent they have access to by staring blindly at what immediately meets the eye – an individual’s current performance – and totally overlooking the story behind it in the process.

Performance blindness in business

This extreme waste of potential caused by poor talent identification is by no means only a sporting phenomenon. Many business executives and companies also suffer from high performance blindness. This often manifests itself in them becoming too obsessed with figures and results. Someone who has led a thriving business in an industry where the majority of companies are doing well, for instance, might appear to be a more attractive candidate for a high-level role than a similarly skilled or even better qualified candidate who has led a struggling firm in an industry in which most companies are failing.

In reality it is much more revealing to look at what people have accomplished in the context in which they accomplished it than than to look simply at results. This is why the best talent scouts in the world meticulously study the circumstances in which performances are created. In their splendid book, The Talent Masters, Ram Charan and Bill Conaty described how General Electric’s charismatic chief executive, Jack Welch, would make a point of giving the highest-percentage bonus in the company to a manager who failed to hit their targets. This clearly makes the point that excellence is dependent ultimately on the circumstances in which it occurs – the chosen manager might have coped with a terrible business environment better than anyone else in the industry.

It’s important, so let me say it again: don’t judge potential using numbers alone. Dig below the surface to learn how the numbers were achieved or what stood in the way that might have prevented them from being better. As Charan and Conaty emphasise, a person could miss a target because the boss insisted that they retain a weak team member, or because the price of a critical resource suddenly spiked. Of course, all this is not to say that digging beneath the results is only important when somebody missed their targets. It’s just as crucial when someone met the targets.

Was a manager successful more because of favourable market conditions rather than because they were a competent decision-maker? Did they sacrifice team members or long-term goals along the way to achieving their goals? Or was their success truly down to the fact that they excelled in all their responsibilities?

In order to know the right questions to ask, and in order to be able to answer them, you must have the courage and will to get up close to your people. There is no shortcut. Spotting talent that whispers is not something you can do from behind your desk in private. This is first and foremost because the process of spotting potential is defined far more by questions involving why, when and how than by questions about what.

As Stephen Francis puts it: ‘I want to know their stories. I want to know what these people are all about and how they became who they are.’

2. Understand the difference between a fatal flaw and an opportunity

Consider this equation by Timothy Gallway, author of The Inner Game of Tennis:

Performance = potential – interference (P = p – i)

So performance is how well you actually do, potential is what you are truly capable of and interference refers to the factors that block the release of the potential. These come in all shapes and forms, including lack of knowledge, personal bias, a current bad leader, low confidence, lack of experience and so on.

In an ideal world, in which there were no interference, your performance would be exactly equal to your potential. What you see would be what you got. Such realities are rare, and high performance blindness means that executives, teachers and coaches often overlook unreleased potential. The key to getting better at spotting talent lies in eliminating or managing the interference.

Let’s nip back to the Jamaican Gold Mine and the MVP Track and Field Club, where Stephen Francis explains how he spotted Shelly-Ann Fraser, the world and Olympic champion in the 100 metres:

‘It was obvious to anyone that Usain Bolt had tremendous potential when he was sixteen. It was far more difficult to identify the potential possessed by Shelly-Ann Fraser, who was nineteen at that time. She took 11.7 seconds to run the 100 metres. She always ran well early in her races, but she fell apart technically and lost speed as the race went on. I thought, “Okay, if I can improve her technique and get her to train properly she will improve drastically.” We succeeded in getting her right down to 10.73. Her example shows what it is I’m looking for. I’m looking for a weakness which I believe I can address and which can be decisive.’

Stephen Francis loves weaknesses – he sees them as opportunities for finding the rare talent that everyone else has overlooked. He is rigorous in identifying the interference factors that will accelerate or unblock a person’s growth. After identifying them he asks himself two simple questions: can I eliminate the interference factor, and do I have the time to do it?

Everything he learns about newcomers is matched against his deeply held knowledge of what strengths are crucial for being a top sprinter – and what deficits don’t matter. This approach requires that you refrain from seeing people as fully developed, pre-packaged products. It also requires that he as a coach understands the difference between a fatal flaw that will keep the person from advancing and a solvable issue that offers a real opportunity for development.

This principle is useful in any field. Let’s try applying it in a business context, for example: looking at your team to find a member who, if a small problem with their work was addressed, would suddenly become much more valuable. Perhaps someone is really excellent in all the skills required to be promoted, indeed is better than many people already in that position, but is let down by a poor grasp of IT or finances. With a little training all that potential could suddenly be unlocked. Remember that if someone comes with problems, they also come with potential.

Great discoveries happen only if assessors are willing to suspend their idea of something perfect. Real potential does not necessarily look perfect, and it takes some open-mindedness, imagination and curiosity to identify talent that whispers.

3. Don’t make your gate too narrow

One of the other major reasons that talent is overlooked is that our mental checklist of criteria is often very stereotyped and narrow-minded. In almost any field you care to look at, the majority of ‘prime’ candidates tend to come from narrow channels and traditional backgrounds.

If you wanted to find a programmer you would probably think of searching a technical university, if you were looking for an executive you might think the best place to find them was a business college and if you wanted a teacher, then you’d likely interview people with the appropriate teaching certificates. These channels are well established and have operated with reasonable success for decades and decades. However, hunting just in those narrow and familiar zones won’t find all the talent. When we narrow down our search excessively we risk overlooking a lot of impressive candidates.

As Stephen Francis says, ‘There is no such thing as one kind of winning sprinter. World-class sprinters come in all sizes, and if I begin to narrow my mental model of what a winner looks like there is a big risk that I will overlook potential world record holders. The reward for keeping the gate as wide open as possible is the opportunity to sign a superstar that no-one else recognised.’

The world of sport is almost overflowing with examples of world-class athletes who did not fit the narrow, stereotypical models of what a winner looks like. Take the Swedish high jumper Stefan Holm, for example, who shook the world by winning the Olympic gold in Athens in 2004. What makes Holm particularly interesting is his height. He stands at 6ft (1.81m) which, although by no means short, is almost dwarf-like in the high jump. He regularly concedes six inches in height to his rivals, as well as being several inches shorter than the women’s world number one, Blanka Vlasic of Croatia. Despite this, Holm boasts a personal best of 2.40 metres, and shares the unofficial world record of being able to clear the greatest height – 0.59cm – above his own height. If Stefan Holm had been judged by the usual height standards applied to high jumpers he would have been rejected almost before he started. And if someone had told Stefan Holm that he absolutely lacked the physical characteristics required to become one of the best in the world, he would probably not have been able to mobilise the self-belief necessary to even have a chance of winning. The point is that there is not one truth, one method, one technique, one type of winner. There are many, many ways to achieve the same goal.

Another good example of this is the Brazilian, Garrincha, who Pelé talks of as being the greatest Brazilian player ever, and the best dribbler in the history of football. Not only did Garrincha develop relatively late, he was born with crippled legs, with the left a full six centimetres shorter than the right. After being rejected by several teams because of his abnormal physique, he was finally taken on by the Brazilian club Botafogo. A player like Garrincha possesses none of the physical characteristics most people would believe a world-class footballer needs. Under a system like the ones that were used in the former Eastern Bloc and China – allocated players to the sport which best matched their physical profile – Garrincha, one of the best players the world has ever seen, would have been rejected on the spot, no doubt about it.

The cases of Holm and Garrincha show how important it is to keep an open mind and not to write people off on the basis of mechanistic tests and checklists, a practice that is becoming more and more rife in talent development the world over. Be sure that you don’t fall prey to it – and that includes writing yourself off.

The exact same problem exists in the world of education. History is filled with story after story of famous people whose traditional education failed to help them identify their talent before they went on to brilliant careers. It turns out that about 35 per cent of all entrepreneurs in the US are dyslexic: Henry Ford, Richard C. Strauss, Charles Schwab, Walt Disney, John T. Chambers and Nelson Rockefeller, just to mention some of the most successful. And Virgin boss Richard Branson once recalled, ‘They thought I was a hopeless case at school because I’m dyslexic, although no-one had heard of it in those days. I was always bottom of the class.’

Here we have people who performed poorly and were labelled ‘losers’ in the established system, but who proved to possess enormous potential.

The Beatles show us two more classic cases of untapped talent. Paul McCartney went through his entire education without anyone noticing he had any musical talent whatsoever, as did George Harrison.

As Sir Ken Robinson, a leading thinker on education, creativity and innovation, put it: ‘There was this one teacher in Liverpool in the ’50s who had half the Beatles in his class and he missed it. I don’t mean to say that you have to have failed at school before you can be a success, but an awful lot of people who did well after school didn’t do well in school. And the point about this is that talent is often buried deep; it’s not lying around on the surface. But our education systems at the moment are still very focused on a certain type of ability, and the result is that many very brilliant people are marginalised by the whole process.’

There are plenty of examples in any field of people who were originally tagged as ‘unsuitable’ because they didn’t conform to some standard size, quality or look, but who nonetheless ended up performing extremely well later on. In his book The Rare Find, Georg Anders describes how in 2006, Facebook tried to break free of this pattern by launching a programming puzzle on its site, which later became known as the Puzzle Master. The puzzle was supposed to function as a test to find potential IT engineers and was so complicated that most people had great difficulty solving it.

Behind this idea was the assumption that there had to be masses of excellent IT engineers out there who had not found their way to Silicon Valley, and who had maybe got stuck in ordinary jobs elsewhere. The puzzle was an innovation designed to draw people like that out of the woodwork. Anyone could try their hand at it and send their solution to Facebook’s head office in Palo Alto. The most successful ‘applicants’ would subsequently be called for interview.

It proved to be an extremely effective recruitment tool. By early 2011, Facebook had hired 118 people through Puzzle Master – almost 20 per cent of all its IT engineers. Many of them were college dropouts. Generally speaking, the puzzle seems to have offered a way to identify talent in people who had not trodden the traditional path, the kind of people who would almost certainly have failed miserably in a traditional company application procedure.

Facebook’s Puzzle Master demonstrates the same principal as Stephen Francis and the MVP Track and Field Club: it proves that the world is full of overlooked talent. It is really worth challenging one’s own stereotypes as to what talent looks like and spending time and energy looking in places where the competition does not look.

4. Put passion above skills

One of the most striking things about the MVP Track and Field Club in Kingston is the Spartan training facilities. You don’t expect to see the world’s best sprinters running and training on a grass field, but nonetheless, this is the situation at the MVP’s training ground. The club provides the absolute basic necessities but no more. Nor does Stephen Francis have any plans to upgrade the facilities – in fact they are part of the way he tests new sprinters. Not by asking newcomers what they think of them directly; he watches their reactions. Are they interested in comfortable, impressive facilities, or are they simply driven by a deep-seated ambition to be one of the best in the world? As he puts it, ‘The most important thing a man has to tell you is what he’s not telling you.’

To Stephen Francis, the passion and hunger to be better today than you were yesterday is one of the most important indicators of the ability to succeed. He is not picking the fastest or strongest sprinters. He wants people with cunning and resilience, people who are able to bounce back from adversity. Once some basic level of competency is present, the key question stops being: what can you do today? Instead, it becomes: what can you learn today that will change your performance tomorrow? And what are you willing to do for it?

Stephen Francis says: ‘I am not at all keen to use the word “talent”, because in many people’s minds this rarely involves hunger and hard work. Take, for instance, Brigitte Foster-Hylton [100 metres hurdles world champion]. When she came here as a 25 year old she ran the distance in 13.3. After the first year she ran it in 12.7. This convinced me that she could go all the way. She is in every way a role model when it comes to seriousness, single-mindedness and the attitude she brings with her to every training session.’

These are exactly the qualities that Angela Lee Duckworth, Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, has noticed in her studies of successful teachers, sales people and students. People who accomplish great things, she found, usually combine a passion for a single mission with an unswerving dedication to achieve it, regardless of obstacles and the length of time it might take. Duckworth calls this quality ‘grit’ and has even developed a test to measure it, which she calls the Grit Scale. It is a deceptively simple test, in that it requires you to rate yourself in regard to twelve statements, from ‘I finish whatever I begin’ to ‘I often set a goal but later choose to pursue a different one’. It takes only three minutes to complete, and it relies entirely on self-assessment, yet when Duckworth took it out into the field, she found it was a remarkably good predictor of success.

Grit is invisible on most resumes. It’s hard to spot in a brief interview. Yet in profession after profession, it turns out to be the factor which decides who will exceed expectations and who will end up as a great disappointment.

A good story of how grit can manifest concerns Bob Gibbons, a former accountant, systems analyst, furniture executive and insurance salesman from North Carolina, who made his name as one of the most highly regarded college basketball recruiting analysts in the US during the early 1980s. In 1981 Gibbons was introduced to an eighteen-year-old boy from North Carolina. Although he had been ditched by the Laney High School basketball team, Gibbons felt there was something special about him. ‘I saw a 6′3″ player with explosive athletic ability,’ Gibbons has since said. What impressed him most, however, was not the boy’s performance on the basketball court; it was his attitude. After a high school tournament in North Carolina in 1981, he approached Gibbons after the match and introduced himself.

‘Hello, Mr Gibbons. What did you think about my game today, and what can I do to improve?’ he said.

The lad’s name was Michael Jordan.

That season, Gibbons rated Jordan at 98 on a scale of 1–100, thus labelling him, in his opinion, the best high school player in the country. Most of the other scouts preferred players whose potential manifested itself in more black-and-white ways – those with very high scoring averages, for example. But Gibbons was convinced that the character traits he had seen in the young Michael Jordan were far more important than a high scoring average. History has certainly vindicated that view.

What characterises the world’s best talent spotters is this ability to look into people’s psyches and figure out how deeply they want to achieve something, and why. They have the courage to focus on a candidate’s underlying character traits and motivations, rather than getting hung up on classic measures of ability. Not that performance, experience and the statistics that measure them are not important – but they are far from the whole show. When we get to know a person intimately, and understand their mindset, their hungers and their history, we can develop insights that will enable us to make an informed judgement about their true potential.

A final word about high potential scouting

It takes courage to look beneath the surface in this way. Had Stephen Francis not had the courage, Asafa Powell would probably never have surfaced. It means having the knowledge and foresight to select a tiny, pale strawberry which is not yet ripe rather than a juicy red one which will soon start to rot.

As Stephen Francis explains: ‘If you want results right away, which is what most coaches aim for, or if you’re under pressure, you will only see an athlete’s performance. It doesn’t occur to you to delve behind that performance and find explanations for it. That is why people overlook the athletes with the greatest potential – because of lack of courage.’

We are often so afraid of making a mistake that we just play safe, to ensure that we at least do not make fools of ourselves. In this way, talent spotting becomes an attempt to avoid failure rather than an ambitious quest to find truly exceptional raw material.

Following the four scouting principles presented in this chapter will not guarantee that you make the right choice every time, but it will enable you to paint a much clearer picture of a person’s potential. Even the very best talent spotters don’t always get it right. In fact, they’re struggling to get it right more than 50 per cent of the time. That’s the way it will always be when you’re trying to see something that doesn’t actually exist yet. The whole thing is educated guesswork. What you’re really trying to do is create an arbitrage. If you’re right 25 per cent of the time versus rivals who are right 20 per cent of the time, you’ve created a 5 per cent arbitrage opportunity, and perhaps that 5 per cent will let you sprint ahead of the rest of the world, creating your very own MVP effect.

What you should never forget about

TALENT IDENTIFICATION

1. The world is full of overlooked talent. Driving it to the surface requires that you rethink how and where you look. If you look in the same way and in the same places as everybody else, you’ll get what everybody else gets.

2. Current performance can certainly be a strong indicator for potential, but that’s far from always the case. Great potential does not necessarily manifest itself in current top performance.

3. Having a crystal clear understanding of the core competencies that drive success in a particular role will give you the freedom to look for and correctly identify relevant talent in many different places.

4. We typically hire for skills and fire for attitude. Start doing as Stephen Francis. Hire for attitude!

5. Shut up and start to listen! Talent identification is not about talking. It’s about listening. Listen for the story, the theme and the reasons driving performance. Listen for what people say without saying it out loud. Listen for what you can’t read in a resume.