On the day the choirmaster first came to St Pölten, 100 miles distant to the east Kara Mustafa was in Ungarisch-Altenburg; and his Master of Ceremonies speaks of the dust rising thickly as the troops marched, so that one man could not recognise another.1

Three days later the Grand Vezir reconnoitred the ground between Schwechat and Vienna. He made his way first to the Neugebäude, a palace built by the Habsburg emperors on the spot where Sultan Suleiman the Lawgiver was believed to have camped during the siege of 1529. For this reason, and because it faintly imitated the Turkish style of architecture, and overlooked superb gardens with clipped alleys, with aviaries orchards and a menagerie, Turkish travellers in the past had greatly admired the palace.2 Kara Mustafa may have wished to show his respect for that mighty predecessor whose venture against Vienna he hoped to surpass, but he also quite certainly regarded the building as a prize worth protection. There could be no question of sacking or despoiling it; and a strong guard was put there. He enjoyed his siesta, he rode forward to look at the city ahead, and then returned to Schwechat. But he was not a wise commander and it was already clear that he was unable to control his forces. The same day, and only a few miles off to the right, Fischamend on the shore of the Danube was raided and, according to the Master of Ceremonies, large stocks of timber were utterly destroyed: but a siege of the kind which Kara Mustafa had in mind required timber for the galleries and trenches of the miners.

On the next day, Wednesday 14 July, he moved forward to the slopes which look down towards the city from the south; the valley of the Wien was immediately in front and farther back were all the other features of military significance—the Canal, the Danube, the hills of the Wiener Wald behind the city, and the contours around the suburbs.* Here he called his council. Obviously, his lieutenants and engineers had been making their plans, and the time had come to settle finally and formally the dispositions for an assault on Vienna. They were based on a conviction (which appeared to justify the whole general strategy of an attack), that the fortifications could be breached in the sector adjoining Leopold’s palace, the Hofburg.3 Here the Wien curved away from the walls. From the higher ground on its left bank there was a fairly gentle gradient down to the glacis and counterscarp; the drainage appeared good; and from this point the approaches could conveniently be dug. Kara Mustafa had been told all this before. Now he was able to see for himself the force of the proposal. Even while he stood viewing the scene, the enemy tried frantically to destroy the buildings and garden-walls of the suburb, where they came closest to the bastions opposite the Hofburg; but the chances of exploiting so favourable a site remained very high. Moreover, the arguments against any other course of action were strong. If he made his approaches opposite the eastern wall of Vienna, they would have to begin close to the waters of the Wien, which would be likely to seep into them; if it rained hard, mining in this area would prove impossible. Farther round, the terrain favoured diggers and miners, and the rising ground at the back provided a good site for artillery. Engineers and gunners here had a chance of combining and concentrating their power to the best advantage.

Without hesitation the Grand Vezir instructed the main force of his army to camp on the other side of the Wien, between the villages of Gumpendorf and Hernals. Many detachments were sent further, to settle along a broad band of ground (as far as the village of Döbling), in this way circling round the city west and north. Other troops would be stationed in the suburb of Rossau,4 adjoining the canal and relatively close to the city defences.* The pasha of Timisoara commanded his contingents here, together with Janissaries, with units from Anatolia and a whole miscellany of remote Ottoman provinces.5 A smaller if still formidable, division stayed on the right wing, east and south-east of Vienna, at St Marx and elsewhere.† The Viennese observed with dreadful anxiety their opponents’ swarm of tents, now being placed in a grand if irregular crescent which gave an appalling, exaggerated idea of the total force of effective fighting men encamped around them.6

Kara Mustafa sent in a summons to surrender, framed in accordance with the customary Ottoman demand on such an occasion.7 A Turkish officer rode up to the counterscarp with a document, handed it to a Croat soldier and awaited a reply. ‘Accept Islam, and live in peace under the Sultan! Or deliver up the fortress, and live in peace under the Sultan as Christians; and if any man prefer, let him depart peaceably, taking his goods with him! But if you resist, then death or spoliation or slavery shall be the fate of you all!’ Such, embroidered in rhetorical language, was the message. But Starhemberg curtly dismissed the messenger and continued to wall up the gates. Kara Mustafa, says the Master of Ceremonies, bade the guns speak.

The defenders were now compelled to reckon with a whole set of possibilities: an immediate general attack, feint assaults at certain points combined with real attacks on others; or a gradual and systematic destruction of the defence-works. But the enemy’s preparations soon gave away clues which became progressively easier to interpret.

On that first day the Turkish command, bringing up quantities of men and a tremendous train of baggage, horses, camels, guns and equipment of every kind, seemed occupied in building a new city of their own. Only a few roving detachments ventured close to old Vienna, to be smartly repulsed. The focus of Turkish activity lay south of the Burg. Well to the rear, the Grand Vezir’s tents were placed, and accommodation was prepared for treasury, chancery and offices of justice. The stores accumulated. Large forces were close at hand, and grouped into three divisions; to each was assigned a frontage for their approach to the city, in an area which lay on both sides of the road leading from the village of St Ulrich to the Burg-gate. This road sloped gently down, and then crossed the glacis to the counterscarp. At intervals there were walls and buildings still standing, also walled pleasure-gardens, and among them a building named the Rotenhof next a garden which belonged to Count Trautson. Here Kara Mustafa put his own forward base, within gunshot—about 450 paces—of the walls of the city. The Turks were delighted by the shelter to be found in so advanced a position. One of them believed that there was no precedent, in the long and glorious history of the Ottoman empire, for a siege in which the soldiers of Allah could actually ride under cover in this way as far as the points of entry into the trenches.8

In this advanced position, Kara Mustafa naturally assigned himself the place of honour in the centre; he was to be assisted by the Aga and Prefect of the Janissaries with the troops under their command, and by the beylerbeyi of Rumelia with his. On the right he put the pashas of Diyarbakir and Anatolia with Asiatic contingents, and some more Janissaries. He gave the command of the left to the pashas of Jenö and Sivas, led by the Vezir Ahmed. On the same day, Wednesday the 14th, he himself crossed over the Wien to his ceremonial tent in the main camp; and during the night the troops of the centre, right and left, began digging their approaches towards the fortifications of the city. The centre faced the projecting angle of the counterscarp opposite the Burg-ravelin; the right wing of the Turkish position around St Ulrich faced the Burg-bastion; their left faced the Löbel-bastion. Early next morning batteries started firing from the height immediately behind them.

Leopold’s envoy Kuniz and his band of interpreters, after their long journey from Istanbul, found themselves assigned a pitch only a few hundred yards from St Ulrich. They would soon be scheming to get into touch with the garrison, not much farther off. Serban Cantacuzene, Prince of Wallachia, took up his quarters in the neighbourhood of Schönbrunn. Our poor friend Marsigli, who had been captured by Tartars and sold by them to Vezir Ahmed, was now a cook-boy and drudge at Hernals.

The defenders continued to palisade the counterscarp. Now that Starhemberg understood the enemy’s tactic he had his own artillery moved into position, with the strongest concentration of pieces near the Hofburg. Other matters absorbed the councillors assembled in the town hall. The number of strangers in the city still frightened them, the scare of the Schotten fire suggested that traitors were at large: they wanted a complete census of the population household by household. The storage of the ammunition had not yet been settled. Next, they tried to decide how to use their manpower, and allocated 800 men to the burgher companies under arms, 120 to the watch, 180 to duties on the Dominican-bastion,9 and another 180 to assist their Junior Treasurer George Altschaffer in his multifarious duties. His office was indeed the chief executive agent of the city councillors. As the siege continued, both they and Starhemberg used it unsparingly for a miscellany of civilian and semi-military chores.10

During the day a fragment of brick or stone, dislodged by an enemy shot on the Löbel-bastion, hit Starhemberg on the head but he soon returned to work.

After dark the garrison tried its first sortie. The men were frightened, some turned back without leaving the shelter of the counterscarp although the others pushed forward. Casualties were few and the experiment was not discouraging, with a certain amount of damage done to the enemy works. It was therefore repeated more confidently twenty-four hours later. Nevertheless, by the morning of the 16th the Turks had already advanced so fast that they were only 200 paces from the salient angles of the counterscarp. Fortunately the preparations to resist them were also nearly complete. The Burg-gate, adjoining one side of the bastion, was being dismantled and the timber removed. A gallows was put up, as a warning to lawbreakers at a time of siege. The re-storage of powder continued. A new mill to make it was started in the moat itself. On the whole the defenders began to settle down, although depressed by the speed and scale of Turkish activity.

They had good reasons for their fears. Kara Mustafa began to carry out his next great move, a total encirclement of the city.11 He went himself to survey the whole position, first from a point somewhere on the lower slopes of the Wiener Wald, and then from a suburb nearer the walls. He gave fresh orders to Hussein of Damascus, and to the Princes of Wallachia and Moldavia. In consequence, a strong force crossed the shallow waters of the Canal into Leopoldstadt and the islands. They drove back Lorraine’s rearguard under Schultz, which retreated towards the last of the Danube bridges. The Turks fired the buildings in Leopoldstadt and took up new positions in order to face Vienna from this side. Shortly afterwards they built bridges of their own, above and below the city’s fortifications, to connect Leopoldstadt with the right bank of the river; they constructed various batteries and breastworks opposite the north wall held by Starhemberg’s men.* As a result, when the defenders had dismantled the bridge which in normal times linked the city and the suburb, Vienna was completely cut off and surrounded. Supplies coming downstream were barred by the Turkish bridge crossing the Canal to Rossau. A bombardment at close quarters from the north was inescapable. If they wished, the Turks could try an assault from this side while pressing towards the Hofburg from the south at the same time. It had also to be considered that if Thököly ever came up along the farther bank of the Danube, he would find it easier to reinforce the Turks for any action against the city; while the Turks could then assist him against Lorraine’s troops. A minor consolation for Starhemberg was that the ground rises fairly sharply from the bank of the Canal towards the centre of the town (as the Romans had noted centuries earlier, when they settled here), which made any attack from the north more difficult. Indeed, Kara Mustafa had already committed his main force to the approach from St Ulrich to the Burg; and throughout the siege the Turks never in fact tried to feint, or to mask their plans. The Grand Vezir was a bold and thoroughly unimaginative commander. As time passed Starhemberg must have realised this weakness in his opponent.

Kara Mustafa, on the Saturday, was able to visit Leopoldstadt. He siesta’d amid the ruined splendours of a Habsburg residence, the Favorita, and returned over the new bridge to Rossau. With the total encirclement of Vienna, the Turks were jubilant. They already spoke of a ‘final victory’ as something in the hollow of their hands. They felt the rhythm of their own triumphant advance; the batteries fired, the working-parties pushed forward the trenches and galleries, the guards took turn and turn about; while the musicians of the Grand Vezir, of the Aga of the Janissaries, and of all the pashas, began to play at every sunset and dawn.

Indeed the rhythm of a routine was quickly imposed on assailants and defenders alike, to be repeated daily for a week, until 22 July. It was felt in all the sectors into which the siege divided: behind the Turkish approaches, in the approaches themselves, along the counterscarp and moat and walls held by the garrison, behind the walls and in the streets of the city, and finally in Leopoldstadt. It affected somewhat less the Turkish detachment and the cavalry regiments of Lorraine which faced one another, at a considerable distance from Vienna, across the main stream of the Danube. Each of the sectors deserve attention, in order to grasp the complexity as well as the general pattern of these grim proceedings.

The initiative stemmed from Kara Mustafa. His headquarters were those splendid tents erected in the centre of the main Turkish encampment, and here he lived in ostentatious luxury. He gave formal audiences, to the envoys of the Magyar lords Batthyány and Draskovich on 15 July,* or to the Aga who came direct from the Sultan on the 19th. Here also he honoured men with the robes which signified promotion in the Ottoman empire. Close by were the other centres of administration, judicial and financial. But of greater immediate significance was Kara Mustafa’s forward base, in the Trautson garden. It was set up in the shelter of the garden wall, a timber structure strengthened with sandbags. A little farther forward a hole was knocked through the wall, giving the Grand Vezir direct access to the trenches. As the days passed it seems as if more and more of his personal equipment was brought from the camp to the garden. From here he made his periodical tours of inspection in the Turkish trenches.

Christian surveyors who later examined the site gave unreserved praise to the layout and construction of these siege-works.12 They found that, with all its appearance of bewildering elaboration, the system of approaches and parallels was admirably suited to the ground. Approaches led more or less directly across the glacis towards the three salient angles of the counterscarp in front of the Burg-bastion, the Burg-ravelin and the Löbel-bastion.† The Turks naturally describe the force aiming at the Burgbastion as their right flank; and here the approach began from the so-called Rakovitsch garden and was duplicated on each side, half-way along its course, by other trenches which proceeded in the same general direction. Parallels were thrown out to the left and right; on the extreme right, they were connected once more by another approach. This was one wing of the main Turkish front. Its parallels were linked with the system of approaches, even more elaborate, in the centre of the whole position. Here three main avenues, one of them coming direct from Kara Mustafa’s entrance by the Trautson garden, converged towards that part of the counterscarp opposite the Burg-ravelin. They were linked by a similar dense series of parallels, which extended towards the approaches on the left wing. One of the latter likewise began its course by branching off from Kara Mustafa’s main access to the central network; then, having gained sufficient ground to the left, it turned direct to the Löbel-bastion. Two more approaches followed the same course; one was the route which connected the parallels at their farthest extension on the left.

In the construction of this astonishing warren the Turks complained of the stoniness of the soil, but the corps of labourers worked (or were forced to work) extraordinarily well. They dug deep, and were therefore protected by high entrenchments as well as by the timber roofing inserted at many points. Much larger spaces were hollowed out at intervals in order to accommodate large bodies of troops. Batteries were installed and, when the system was complete, more guns and timber and ammunition were brought right forward to the edge of the counterscarp. Sorties of the garrison were not only hampered by the soft earth thrown up in digging the trenches, but by the soldiers in the parallels, who protected the labourers as they pushed forward the various approaches.

An important but less effective part of the offensive was the artillery. It had started firing from the slopes behind the Trautson garden. Batteries were then mounted farther down and to the right, very near to where the approaches to the Burg-bastion began; then, below the Trautson gardens by the Rotenhof, as well as away to the left; then, closer and closer to the city. A cannonade was kept up intermittently throughout the siege, though it was apt to be silenced by rain. Its main defects, judged by the best standards of the period, were the lightness of the calibre and the poor quality of ammunition. There can be no reasonable doubt that Turkish artillery of the seventeenth century could not damage the stronger fortresses of Christian Europe with sufficient severity or speed. It has been suggested that the Ottoman officers did not bring their heaviest pieces with them, because the Sultan had originally agreed to have Györ besieged, or possibly Komárom, but not Vienna. More probably they never dreamt of transporting guns of the largest size across the Balkans, while they lacked the resources or expertise to have them manufactured at Buda, the obvious advanced base for all supplies. (From Buda, they actually received much of their very unsatisfactory gunpowder.) Turkish authorities distinguish between weapons of middle and heavy calibre, throwing balls from ten to forty okka13 in weight, and those of light to medium throwing balls between three and nine okka. Others were still lighter. At Vienna Kara Mustafa apparently had none of the heaviest type, reckoned essential for the effective battering of properly built defence-works from a reasonable distance; he had to use seventeen of the medium weights, and ninety-five lighter cannon. There were also no mortars available. In fact his artillery could slaughter men, but do no more than dint the fortifications. In spite of this the Ottoman commanders were convinced that the trench and the mine were the fundamental siege-weapons; gunfire was an auxiliary. For them, this had been the lesson taught by their ultimate success in taking Candia in Crete, in 1669.

The transformation of the glacis by a network of tunnels and trenches, the Turkish battle-front, had its counterpart in the defences of their opponents.14 If it was earlier hoped to obstruct the Turks by burning down the suburbs and clearing the glacis, and this had failed because nothing seemed to halt their progress forward from St Ulrich, it became the more essential to convert the great moat into the most formidable barrier that men could contrive. First of all the Habsburg engineers turned their attention to the counterscarp again, reinforcing it with iron spikes, and with timber baulks set crosswise. At the salients, entrenchments were thrown up behind the area created by the angle, converting these vulnerable points into stockades of peculiar strength. The covered way along the counterscarp was sealed off into sections by building walls across it at intervals so that the attacker would be forced to take them one by one, after prolonged resistance in each. Behind this line of defence, and at a lower level, Starhemberg began to complicate the hazards on the floor of the moat. George Rimpler was his chief technical adviser here. More entrenchments were made, to connect the ravelins with the flanks of the bastions; half-way along such entrenchments block-houses were set up, projecting slightly forward, to enable their fire to command the ground in front of the ravelins. These defences were the so-called ‘caponnières’ of contemporary writings on this abstruse but practical subject. The engineers also paid particular attention to the Burg-ravelin itself, which faced the centre of the Turkish advance. Inside its walls more trenches were dug, and ramparts thrown up; the covered way connecting the ravelin with the main city-wall was strongly palisaded. One flaw in the original design of this ravelin worried the experts, but at this late stage it could hardly be remedied: a plinth projecting from the base of its outside wall, intended to prevent falling stone or earth from filling up the ditch, was too high and blocked a clear view of what might be going on at the foot of the wall. It proved a godsend to the miners of the enemy later on.

Lastly Starhemberg looked at the two bastions; he had to anticipate that these would in due course be exposed to powerful Turkish attacks.* His advisers were fairly satisfied with the Burg-bastion, except that it was ill-equipped with casemates for the purpose of counter-mining, and they contented themselves with throwing up inner works in the usual form of entrenchments and traverses. The Burg-gate was blocked. Then, along the foot of the curtain-wall running towards the Löbel-bastion, a secondary line of defence was constructed; at the point where it approached the Löbel itself an additional piece of work was hastily put in hand. This was an improvised extension of that bastion, designed to give more elbow-room to the defenders there, and to shorten the length of the curtain-wall, making this easier to protect. Even with these alterations there was still wretchedly little space on the Löbel-bastion for men or guns; and the lofty bulwark capping it, the ‘Katze’, remained very exposed to Turkish fire.

The defence was able to concentrate on this stretch between the Burg and the Löbel, because the enemy never made any serious attempt to test the garrison elsewhere. In a single ‘watch’ on 9 August (the only date for which there is a detailed list), out of a total of 2,193 officers and men at the twenty-two guard-posts round the city, over 1,000 held the line between Burg and Löbel.15 Old maps show that elsewhere the counterscarp was reinforced by new works thrown out towards the glacis, but they seem never to have been used or needed. On the other hand, detachments of the garrison tried on 18 July to bring into the town some of the wood stacked outside the New-gate, but were not successful. The Turks, taking cover in the ruined buildings of Rossau immediately opposite, shot down the men who sallied out from the counterscarp.

While the ring of fortifications buzzed with activity, inside Vienna the civilian world struggled to survive under conditions of siege.16 If the schools had closed, the churches soon opened again. Stocks of food were still ample, and prices steady. The flurry of excitement which had first called out the burgher-guards and companies recruited from the artisans, died down when the siege began to follow an orthodox course. The garrison of Lorraine’s infantry was large enough to hold the defences; neither the fighting, nor the spread of illness among the troops, had yet taken such toll that Starhemberg was compelled to use untrained auxiliaries, except at a few points of little importance. The civil administration was gradually being pulled into shape by the commander himself, by Caplirs and burgomaster Liebenberg. A number of useful measures were agreed, and to some extent carried out. Fire-brigades, when incendiary bombs began to fall in quantity, began to do their work admirably; they arrived promptly when a stable caught alight near the Löbel on 19 July and though a quantity of straw blazed away little damage was done. Persistent official pressure now forced all householders to provide themselves with buckets, barrels or skins, kept filled with water; and they had to dismantle roofs made of shingles, in order to lessen the risks of fire. But there were fires, and more companies of fire-fighters were formed to deal with them. Other instructions dealt with the scouring of the streets, the removal of refuse and of dead animals; while paving-stones were dug up, partly for the reason that Turkish shot did least damage if it fell on soft earth, partly because more stone was needed on the fortifications. At the same time timber was taken from damaged buildings. Long lengths made extra palisades and baulks for the works. Smaller pieces increased the supply of firewood, or were dipped in tar for flares to illumine the moat and counterscarp at night, so that the enemy could not creep forward under cover of darkness. In addition the municipal authority organised the inspection of all properties, for a variety of reasons. It wanted to draw up a schedule of the total supply of straw in the town, because the wounded soldiers and civilians needed straw. It wanted all the fodder available, for the horses which were essential for the transport of supplies from one area to another. It wanted a census, to identify idlers and suspects. It again wanted full information about cellars for storage, and empty premises for the accommodation of the sick. Individual members of the inner council of the burghers were charged with these assignments, while the tight little municipal bureaucracy of inspectors and tax-collectors found themselves busy on novel and unfamiliar work.

Some problems were almost insuperable. The administration could not easily get rid of garbage, or even find sufficient burial-grounds for the dead. The Turks cut the conduits of fresh water leading into the city. In spite of orders and plans the growing number of sick and wounded caused terrible hardships, and the apothecaries and the nursing nuns and the City Hospital itself were unable to deal with the casualties of the siege. One strong man did his best to come to the rescue: Kollonics. This churchman had solved the financial problem by putting pressure on the clergy, as we have seen. In the sphere of hospital and medical organisation, he likewise swept aside clerical immunities which in any way hampered the arrangements which he sponsored for the treatment of the sick. He allotted accommodation in different religious houses to the sick or wounded of various units of the garrison, and to the civil population. He called in the help of all the physicians whom he could find in Vienna to assist the regimental doctors. He did in fact improve the medical services, in his own way strengthening the will to resist in the more critical weeks ahead.

The completeness of the siege gradually increased. On two consecutive nights, early on, detachments of the garrison sallied out from the walls. The first, a troop of 80 men, was severely handled by the left wing of the opposing army. The second, of 500, was the last of its kind for many weeks. The main purpose of such raids had been to smash the approaches to the counterscarp, but it was found that these were too well protected by Turkish infantry in the parallels. Cattle raids were of course a different matter; they occurred on a number of occasions, sometimes with official consent. In addition, on 23 July Starhemberg warned the municipality that women were going out of the town to barter their bread with the Turks in exchange for vegetables: too many persons, he said, were climbing across the fortifications. He viewed this with great suspicion, because security was in fact more important than the food supply. Not only by the enemy, therefore, but by a grimmer consideration of their own interests, the Viennese were barred in. The troops on duty had instructions to fire at all trespassers on sight. Even so, private forays by a few who knew the ground must have continued, men scrambling at night along ruined boundary walls to caches of supplies still buried and hidden in the burnt-out suburbs. These would be the routes followed by Starhemberg’s messengers sent out to Leopold and Lorraine later on.

Life was intensely uncomfortable everywhere in Vienna, especially in the quarter bordering the Canal at the commencement of the siege. The enemy guns fired furiously from Leopoldstadt; houses and churches facing them were badly damaged. It was decided to wall up the windows in the neighbourhood of the Rotenturn, the city gate, and Starhemberg placed a heavier armament on the adjoining bastion, which replied very effectively to the Turks. He and his colleagues believed that any embarrasments in this quarter were annoying but not dangerous, so long as Kara Mustafa refrained from a serious attack across the Canal, under the protection of his batteries in Leopoldstadt.

This survey has moved gradually north from the Grand Vezir’s base, across the Turkish works and the Christian defences adjoining the Burg, then to the northern part of the town and to the Turks in Leopoldstadt. East and west, beyond the glacis, other sections of the besieging army were stationed, but inactive most of the time. Still further off, and north again from Leopoldstadt a series of broken bridges blocked the usual crossing of the Danube: here one more Ottoman force stood on guard, facing their enemy. Across the water the Habsburg cavalry would be stationed, but powerless to help the Habsburg infantry locked inside the city.

This garrison was now composed of the regiments (with ten companies each) of Alt-Starhemberg, Mansfeld, Souches and Scherffenberg; half or more of the companies of Kaiserstein’s, Neuburg’s, Heister’s and Württemberg’s; three companies each of Thim’s, and of Dupigny’s dragoons. To these must be added the City Guard. The nominal total of the seventy-two companies amounted to 16,600 men, but their actual strength was approximately 11,000.17 Useful, but of slight military importance, were the civilians who could be mobilised. The most plausible estimate of the size of the ancient burgher-companies from the eight city ‘wards’, each led by a captain, lieutenant and ensign, allows them a combined total of 1,815 excluding their officers. But in this supreme emergency, when all ordinary business came temporarily to a standstill, public-spirited individuals took the lead in organising groups of volunteers and employers recruited their work-people. One prominent company was formed by Ambrosius Frank, a well-known inn-keeper, a member of the outer council of burghers. The butchers and brewers joined forces and raised a company, the shoemakers and bakers each raised one. Other artisans were grouped together, first in one large unit, and then later into two. Such were the six so-called ‘free’ companies of the city, estimated—at one count—to number 1,293 men. The university authorities, meanwhile, were mustering the students, together with the printers and booksellers, perhaps 700 in all. The big import-export merchants raised 250; they paid their men, and tended to attract recruits from other companies. Craftsmen, office-holders, and servants connected with the court—the ‘Hofbefreiten’—were also organised; and with some hesitation their total manpower can be recorded as 960. Finally, a very useful small group of eighty huntsmen and sharpshooters was ready to serve. The municipality could therefore put about 3,000 at Starhemberg’s disposal, the university and the merchants and the court about 2,000. The organisation of these 5,000 was always rudimentary, nor is it clear how many of them were available in the very early stages of the siege. But the civilians helped with guard-duties, and they did much of the repair-work.

In status the first citizen was the burgomaster, John Andrew Liebenberg.18 He is a puzzling character and, unfortunately for patriotic Viennese chroniclers, not an ingratiating one. Although he had played a very honourable part during the plague-year of 1679, he subsequently found it difficult to clear his financial accounts with the Treasury. He filled all the important city offices in turn, before becoming burgomaster, but did not seem to enjoy sufficient private revenues of his own to free him from a suspicion that he was somewhat mean and unscrupulous in money matters; yet there can be no doubt that he died in considerable poverty, from which his family suffered later. His house, facing on to the square of Am Hof, close to the administrative office of the city treasury and the municipal armoury, was a business centre of the highest importance during the crisis. The town hall stood a little farther north in the Wipplinger Strasse, the ordinary meeting-place of the city councillors. A large proportion of the members of the inner council were even older than Liebenberg and, like him, died of illness and strain before the Turks were finally driven off. They all, or nearly all, were assigned duties of considerable responsibility. They supervised the distribution of bread or wine. They were captains of the burgher companies.

On 10 July, shortly before the Turks reached Vienna, while so much still needed doing if they were to be resisted at all, it was decided to amalgamate the inner council with the municipal tribunal, the Stadtgericht. The members of the court, headed by wealthy Simon Schuster who lived on the main street leading down to the Rotenturm and the bridge over the Canal, were brought in to share the duties and responsibilities of the senior councillors. But the outstanding citizen during the crisis was Daniel Fotky, the rich and energetic senior treasurer who was often sent by the townsmen to settle difficult matters with Starhemberg or Caplirs. He handled every kind of business, and in the intensely anxious weeks of August seems to have deputised for Liebenberg, whose strength failed rapidly. When the burgomaster died on 9 September Fotky took over all his duties. A worthy colleague of these men was Hocke, the syndic. Not a Viennese by birth, he had come to study law at the University there in his youth. He now proved a tireless and conscientious official, and later wrote what was certainly the best contemporary history of the siege. Posterity is indebted to him on both counts.

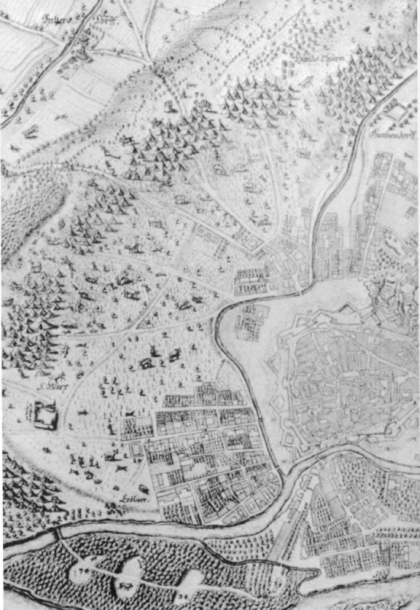

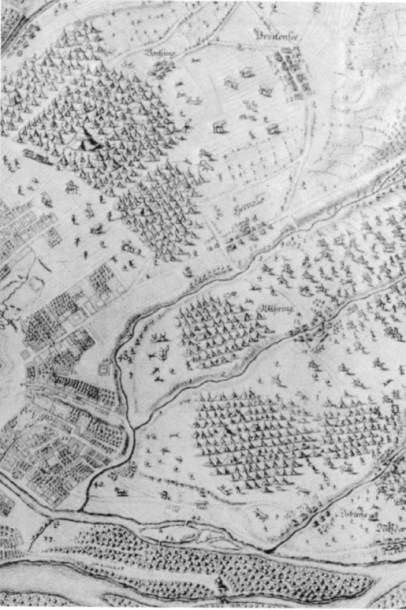

* See illustrations IX and XI.

* These villages and suburbs are named or numbered in illustration IX. Beyond Gumpendorf the ceremonial tents of the three headquarters in the Ottoman encampment are conspicuous, and the suburb of St Ulrich lies in front of them. The houses of Rossau surround no. 26

†See illustrations VII and IX.

* The Leopoldstadt suburb is visible in illustration IX, between the Canal and one of the main channels of the Danube.

* An important point connected with the submission of Batthyány and Draskovich was that they undertook to send large stocks of provisions from their lands to the besieging army at Vienna.

* see illustration VI.

In the third week of July, Kara Mustafa still had every reason to be satisfied. The army of his opponents was sealed off from Vienna along the length of the Danube from Krems to Pressburg, and their reinforcements were clearly very far away. His own forces encircled the city, of which the main line of defence had now been reached; and surely his men would soon move across the counterscarp into the ditch beneath the curtain-wall. The garrison, no doubt, was full of fight. It might continue to struggle against overwhelming odds for a week or two longer, but with every day that passed it would get less effective. Everything, so far, justified his own actions during the previous six months; nothing suggested that he was open to a serious attack from any quarter. The siege could proceed systematically, without running unnecessary risks a thousand miles from Istanbul. His men, Kara Mustafa recognised, had not shown themselves able to rush the counterscarp. Attacks made under cover of darkness, and the impact of Turkish mortar-fire and grenades, were insufficient to help them forward. The Grand Vezir therefore sanctioned the next stage of an assault, the laying of mines to force entry from his approaches into the counterscarp. These approaches, and the whole complex of lateral communications, came nearest to the defences at three salient points, in front of the two bastions, and also in front of the ravelin which stood between them. Here, after much hard digging, the Turks prepared to mine; an officer was sent forward by Kara Mustafa to inspect, and to report back to him. For some unexplained reason, the miners in the centre lagged behind their colleagues to left and right, and did not complete their preparations so quickly. On 22 July the Turkish artillery bombardment suddenly became tremendous. Kuniz heard what was afoot, and tried to send a warning into the town. The Austrian command, even without this intelligence (which only arrived two days later) guessed enough to know what was coming. Starhemberg ordered every householder to arrange for the inspection of his cellars, and to report immediately if sounds were heard underground; and he considered the possibility that traitors in Vienna might tunnel out towards the Turkish lines. Most of Friday 23 July things were quiet, unusually quiet;19 then, between six and seven o’clock, two mines, opposite the two bastions, were exploded by the Turks who immediately stormed the palisading which protected the counterscarp. But these mines were ineffective, and after violent fighting the position hardly altered.

Next day the bombardment paused towards the evening, when rain fell. During the lull the defence brought up new, and removed faulty, guns on the bastions; but at the same moment some citizens were shuddering over the rumour that enemy soldiers were creeping up a sewer. Others boldly re-opened their shops, closed during the day. Others again went to church; and in St Stephen’s the congregation and preacher were startled by a ball which burst into the building and struck the organ.

On Sunday the Turks at last exploded their mine opposite the ravelin. It knocked down part of the palisading, and ‘volunteers’ poured into the attack while the garrison rallied to drive them out. It was a serious moment, and a number of high-ranking officers were wounded before the enemy moved back to the shelter of their trenches. In fact this assault set a pattern for a whole series of explosions, attacks and counter-attacks in the course of the following week. The other novel element, introduced on 26 July, was the countermining of the defenders, an art which they only mastered gradually. A few bold improvisers had offered their services to Starhemberg, especially Captain Hafner of the City-Guard, but they needed practice and experience before becoming efficient. The garrison relied more on their artillery, and on the bombs or grenades which they threw from the counterscarp into the Turkish works and the Turkish squads of labourers. On 27 July, at last, some attackers jumped into the covered way opposite the Burg, but were promptly thrown down into the moat and slaughtered by Christian troops at this lower level. On every one of three days following, the battle was furious. Inch by inch the Turks broke down the defences of the counterscarp. The effect of their bombs was to destroy the palisading, and after an expensive counterattack had managed to drive back the troops which stormed in after the explosions, it was necessary on each occasion to repair the breach with more timber and fresh digging; but a stage had now been reached when these outer works could no longer be strengthened, and they could only be patched with great difficulty. It seems premature, but Starhemberg was already at this time making arrangements to fight inside the walls. He listed assembly-points for the burghers and other untrained forces, he silenced all bells and chimes except for the striking of the hour from the church towers, he decreed that the great bell of St Stephen’s should only sound to summon the citizens if the worst of all emergencies should befall and the Turks entered the city.

Occasionally there was good news. The Danube rose a little, which made an attack across the Canal less likely. A large band of students from the University and men from the corps of butchers once sallied from the defences into the open country and brought back cattle; fresh meat had been getting scarce and dear. Unfortunately dysentery spread fast among the troops and civil population. It was the Turks’ strongest ally. The town council set aside the Passauerhof, the property of the Bishop of Passau, as a hospital for these patients. The military authority, anxiously totting up the losses caused by mining and storming, now saw them multiplied by this new factor, and began to look around for reserves. The companies of ‘Hofbefreiten’ were deployed for the first time, and posted to the ravelin by the Stuben-gate. It was not a post of great significance, but they freed better soldiers for use elsewhere. This was the period of Vienna’s greatest isolation. Starhemberg, from 24 July to 4 August, was in touch neither with Kuniz nor Lorraine. It hardly mattered, provided that the Turks continued to stand in front of, and not in or under the counterscarp. The defenders of the city also pinned their hopes to earlier reports that a relieving army would arrive in Austria in the fairly near future, and they still enjoyed plentiful supplies of bread and cash. The troops had been paid punctually, and large quantities of corn were ground. But if disease continued to spread and stocks dwindled and the enemy advanced, which all appeared probable, then the morale of even the commanding officer was vulnerable. The inveterate pessimism of Caplirs would prove as infectious as a bout of plague.

On 31 July the Christian forces listened to their own bands making excellent music, so they said, with drum and pipe. In the Turkish camp the Sultan’s special envoy Ali Aga took his leave of the Grand Vezir before returning to Belgrade, and the Turkish musicians were also commanded to strike up.20 The accounts of the besiegers and the besieged serve to show that the enemy’s music roused scorn on both sides, while each continued to fight desperately in front of the Vienna Burg. Every foot of this small area was disputed, in the first week of August as in the last week of July. The Turks, having brought their foremost trenches as far as the palisades guarding the counterscarp, now threw up the earth to such a height that they gradually raised themselves sufficiently to command a partial view of the defence works, while at the same time they also tunnelled underneath their own entrenchments. They tried to set fire to the timbers which barred them, and the garrison countered by taking water from the ditch in the moat to put out the fires. Arrows and grenades flew about, as well as bombs and balls and stones. The Christians sometimes fixed scythes to long poles, to strike at the enemy through the palisades. On 2 August for the first time Starhemberg’s men sprung a mine effectively, to the heartfelt satisfaction of the commander who congratulated the officer in charge, Captain Hafner. Arms and legs mingled with the smoke and falling rubbish opposite the Löbel-bastion. Artillery fire normally dominated the forenoon, while in the afternoon and during the earlier part of the evening the mines were exploded, to be followed by one or more assaults immediately afterwards and in the course of the night. At night, too, repair work was carried out by both sides. The Turks began to get into the defences on the counterscarp opposite the Burg-ravelin, because here their tunnelling and their mines had practically obliterated the angles and entrenchments which alone made effective resistance possible. Misdirected countermines at a critical time had even helped them. By the night of 3 August they were at last fairly in control at this point; and a new phase of the siege began when they started shooting down the ditches in the moat on both sides of the ravelin opposite them. The most desperate attacks failed to drive them back, and Habsburg losses were very heavy. One of the most serious was the death in action of Rimpler the engineer. The defenders, retreating from the lost section of the counterscarp, tried to bring back the timbering of the palisades with them, or to burn it; while the Turks dug and mined in such a way that earth fell from the counterscarp into the moat and partially filled it up. Their intention, naturally, was to raise a barrier protecting them from the marksmen posted in the ‘caponnières’ recently constructed to left and right of the ravelin, and so to ease their progress towards the ravelin itself. This obstacle required an assault at various levels, with miners attaching themselves to its base while storm troops mounted as near as they could get to the top of the outside walls.

This descent into the moat, and then the move forward as far as the ravelin, cost the Turks nine more days of furious fighting. While they piled up their earthworks, Starhemberg’s men managed to come along with barrows and trundled earth away. Then the Turks would sally out from their cover in great force, and the garrison came out likewise to repulse them. The Turks dug galleries and boarded them over; in the night of 8 August Daun and Souches with 300 men set fire to some of these galleries. On the 9th, the Turks destroyed a wall connecting one corner of the ravelin with the Burg-bastion. On the 10th they sprung a new mine at the forward point of the ravelin, but it misfired and they had to begin again. The losses on both sides were very severe and, as officers fell, promotion was rapid. In Vienna a new graveyard was opened in the old cemetery of the Augustinians. While one popular officer, Kottoliski, died on the Löbel side of the ravelin, his brother was wounded on the other side in the course of the same night’s fighting.21 The Turks continued to work forward into the counterscarp opposite the bastions, and from the counterscarp into the moat. The cannon from the bastions played on the batteries which the Turks themselves gradually moved forward; bombs sometimes exploded on guns opposite, and fired them off. Yet the brunt of the fighting was in the central position, at the forward tip of the ravelin. The garrison had at length to withdraw its heavier pieces from this area to the main city wall and to the bastions; but at the same time, along the stoutly protected causeway which led forward from the wall to the rear of the ravelin, detachments of troops periodically advanced to mount guard—one detachment relieving another at fixed intervals—in that crucial, most exposed of all positions. As long as possible, also, they held on to points in this section of the counterscarp, and to the caponnières in the moat. Slowly they were forced out. The Turks edged in, were pushed back, and edged forward again. The interminable rota of watches in the ravelin still continued.

The monotony, as always in crises of this kind, matched the suspense. It was difficult to distinguish one mine, one sortie, from others. But in the early afternoon of 12 August, since nothing of note had occurred earlier in the day, something serious was expected. The officer commanding in the ravelin was warned by his men that they could not locate the spot where the Turks were obviously preparing their next mine on the grandest scale. As a spectator observed, even the attackers seemed to pause and wait anxiously. Then, abruptly, the mine was sprung. It was said to have shaken half the town. When the smoke cleared, the same spectator was horrified to see that the combined result of previous Turkish works and the new upheaval was to raise a sort of causeway to the level of the defenders’ first entrenchment on the ravelin, wide enough for fifty attackers abreast. Soon eight Turkish standards were fixed there. The fighting was intense; the garrison recovered some of the ground lost, but at the end of the day Starhemberg had to recognise that his opponents now held a small part of their immediate objective, the ravelin, and could not be driven off. The 12th of August, like the 3rd, was an epoch in the siege of Vienna.

I. The Ottoman Frontier: above, Esztergom; below Neuhäusel

Edward Browne, the English traveller who made these pen-and-ink sketches in 1669, wrote a few years later of the frontier between Christendom and Islam in Hungary:

A man seems to take leave of our world when he hath passed a day’s journey from Rab (Györ) or Comorra (Komárom): and, before he comes to Buda seems to enter upon a new stage of the world, quite different from that of western countries: for he then bids adieu to hair on the head, bands, cuffs, hats, gloves, beds, beer: and enters upon habits, manners and a course of life which, with no great variety but under some conformity extend unto China and the utmost parts of Asia

II. The Habsburg Frontier: above, Komárom, a fortress on the Danube; below, Petronell, a nobleman’s mansion east of Vienna

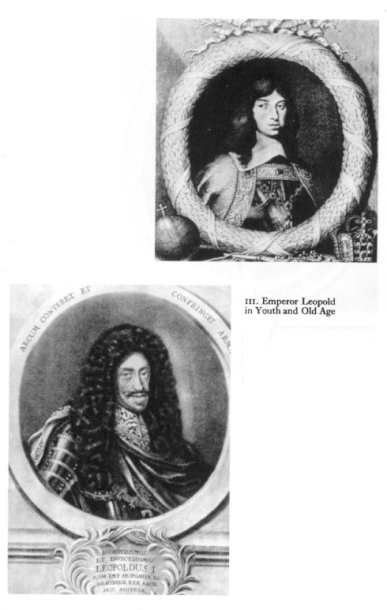

III. Emperor Leopold in Youth and Old Age.

IV. Charles V, Duke of Lorraine

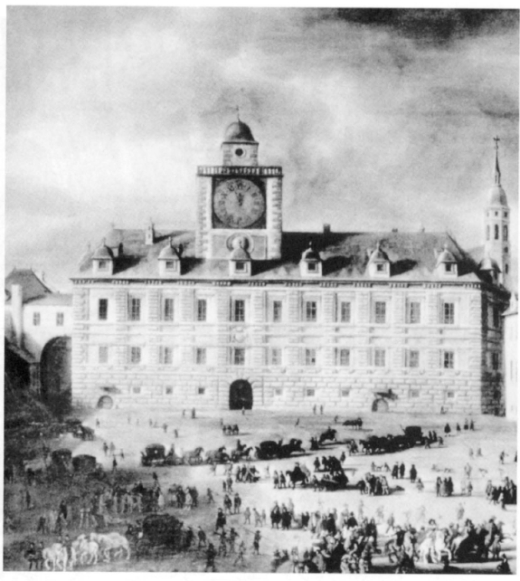

V. The Burgplatz

VI. The Hofburg and the Turkish Siege-Works

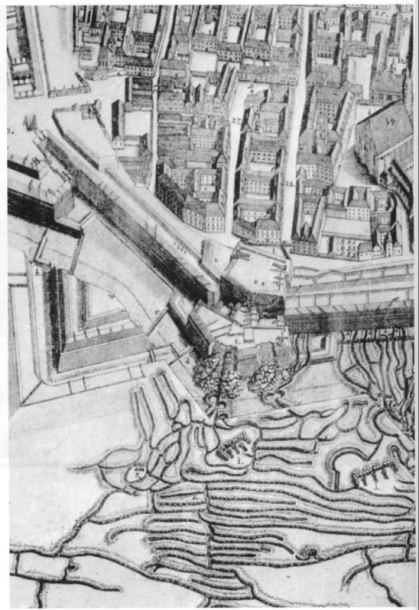

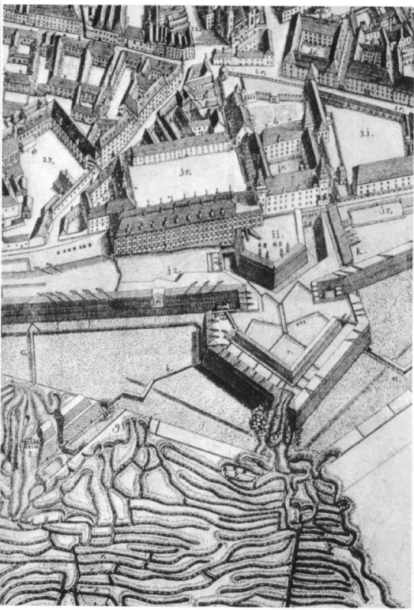

VII. Above, Vienna in 1649; below, a plan of the City in 1683

In the older print (much of it based on a drawing made in 1609) a mediaeval wall still defends the city along the Canal. The plan of 1683 shows the new bastions on this side, and the destruction of the bridge over the Canal by the garrison.

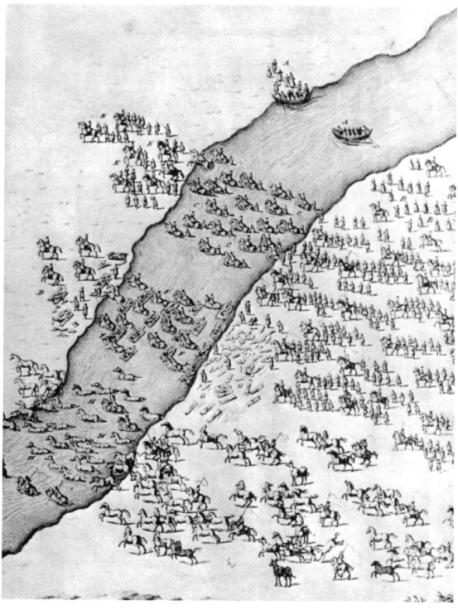

VIII. The Tartars Crossing a River

A, B: women captives; C, E: other prisoners, tied to the tails of the horses; D, F: Tartars getting equipment across on bundles of reeds; G: extra reeds; H: spare horses

IX. The Siege of Vienna

X. Koltschitzki in Disguise

XI. The Danube and the Wienerwald: above, the ascent to the Wienerwald from St. Andrä; below, upstream from Vienna

XII. Passau

XIII. Ernest Rüdiger von Starhemberg

The contemporary idea of a triumphant commander

XIV. John III Sobieski, King of Poland

Another contemporary version of the hero in action