Administrative preparations to receive foreign armies in Austria were no doubt essential. The first duty of the ministers at Passau, as they saw it, was nonetheless the exercise of diplomacy. These armies would only move if the princes of Europe were brought to decide that they consulted their own best interests by coming to the rescue of the Habsburg Emperor. Treaty obligations, appeals to Christian sentiment, an analysis of the military implications if Kara Mustafa permanently lodged an Ottoman garrison in the heart of Europe: these were the major instruments to be handled by Stratmann and Königsegg in their unaccustomed quarters, as they looked to the world beyond the confines of the Danube.

They relied above all on Sobieski, bound by treaty to wage an aggressive war against the Turks in the campaigning season of 1683, and to help in the defence of Vienna if an emergency occurred.

In Poland the French ambassador had been heavily defeated in the course of the Diet’s proceedings. He still hoped that three or four months would be needed to raise the taxes for a new army, quite apart from the time taken in raising and assembling the troops. In any case he believed that some of the Polish provinces, in meetings of their own ‘diets’, were about to mangle the recommendations of the national Diet.1 Aristocratic assemblies, enjoying very extensive privileges, would always be unwilling to tax themselves or their tenantry for the sake of the state, and in particular (so he reported) the governors of Poznań, Vilna and Ruthenia continued in a mood of the utmost antagonism to their elected King. The ambassador admitted to Louis XIV that royal propaganda was active, and feared that too many of the smaller nobility were likely to listen to it, but he still pinned his faith to the slow workings of a political system in which the powers of King, Diet and Senate were held in check by the semi-independent status of the provinces. Time, the essence of the problem when armies had to be raised in the seventeenth century, appeared to be on his side. Yet on some important points de Vitry proved wrong. The provincial assemblies began to meet in the middle of May, and a fortnight later the overwhelming majority had accepted the proposals of the King and the national Diet. The Habsburg subsidy was also beginning to flow, and the military units to take shape.

But the weeks were passing swiftly by and, as they passed, the likelihood of an advance by the Poles into Podolia or farther east faded away. Here Sobieski ran into difficulties. He had intended to use the Church’s money for the purpose of recruiting Cossacks. He greatly respected their military qualities, and wanted to coax them to attack the Crimean Tartars, those important auxiliaries of the Sultan. Innocent XI decided otherwise, and pressed for direct action against the Turks. He ordered Pallavicini, the nuncio, not to transfer any funds to the King unless the Cossacks were committed by the terms of their agreement to fight in Hungary; nor was he to do so before the Poles themselves actually began hostilities. Sobieski expressed immense annoyance at what seemed to him a fatuous denial of ready money, which in the end he secured by promising to get not less than 3,000 Cossacks into action in Hungary by mid-August.2 In fact they never appeared, to his own bitter disappointment.

An aggressive Polish move in the south-east depended on the ‘old’ army of the standing troops. They were encamped under Field Hetman Sienawski within striking distance of Kamenets – which the Poles dearly wished to recapture. But in Warsaw it was reported, on 16 June, that the King himself proposed to move to Cracow at the end of the month, and had ordered Sienawski to withdraw from his advanced position and make Lvov his headquarters.3 The shift of emphasis westwards occurred simply because the combined activity of Thököly and the Turks forced the Poles to mount guard along the Hungarian frontier. No one could be certain whether Kara Mustafa intended to halt at Györ, or march still farther up the Danube into Austria, or cross the Danube and threaten Moravia, Silesia and Poland. For the Poles, the very slow mobilisation of their ‘new’ forces increased the danger of the position. At the end of June Pallavicini almost felt tempted to hope for news of an immediate enemy attack in order to hasten the growth of the Polish army. Sobieski wrote a circular letter to all commanding officers to hurry them on, but clearly little or nothing had so far been done in many districts, above all in Lithuania. To this extent, de Vitry was right.4

Meanwhile the Habsburg army under Lorraine had retreated from Neuhäusel. The Vienna government feared for the security of Moravia, and for the fate of its inadequate force in northern Hungary. It tried to increase the numbers under Schultz’s command by ordering Prince Lubomirski’s men to join him, and also the 4,000 troopers promised by Sobieski in April.5 There was no sign of the latter even towards the end of June, and urgent instructions reached Leopold’s envoy Zierowski at Warsaw to press hard for another reinforcement. In response, on 4 July the King agreed to move Sienawski and 7,000 men still farther west. They would come as far as Cracow,6 unite with the new companies assembling there, and be prepared to defend the upper reaches of the Váh if this proved necessary. It was considered vital to be ready for action when the truce between Leopold and Thököly expired on 21 July.

On the day after Sobieski’s conference with Zierowski, unknown to them both, a messenger set out at top speed on the long journey from Vienna.7 Count Thurn covered 350 miles in 11 days, and arrived at the royal residence of Wilanów outside Warsaw on 15 July. Austria was being invaded, its capital city was in danger, he reported, and the Emperor appealed to the King of Poland for help. In his turn the Count did not know that, while he spoke, Kara Mustafa was completing the encirclement of Vienna and Leopold was on his way from Linz to Passau.

At first Sobieski replied rather vaguely, promising assistance by the middle of August, if the Turks actually besieged Vienna. Much more detailed debate and discussion followed. Thurn gloomily told the nuncio that the facts were undoubtedly worse than anything contained in his dispatches, while the Poles had to weigh the view that the Sultan’s army was now committed to a risky enterprise in an area mercifully remote from most Polish territory. At length the King announced his decisions: to send Sienawski and his 7,000 men to join Lorraine; to prepare to go himself to Vienna if it was besieged by the Turks; and if it was not, to fight in Podolia or possibly Transylvania. But most important of all, he determined to leave Warsaw at once. He had been meaning to go, he had delayed and dithered, and now it abruptly became clear to him that delay was dangerous. Illness, hunting, the birth of a son, the Queen’s health, and purchases of property, had together taken up much of his time in the spring and early summer—the normal period of tranquillity between a winter of strenuous politics and a season of warfare in the late summer and the autumn. Now the sense of a gigantic emergency, and reasons of state, began increasingly to dominate his thinking again.

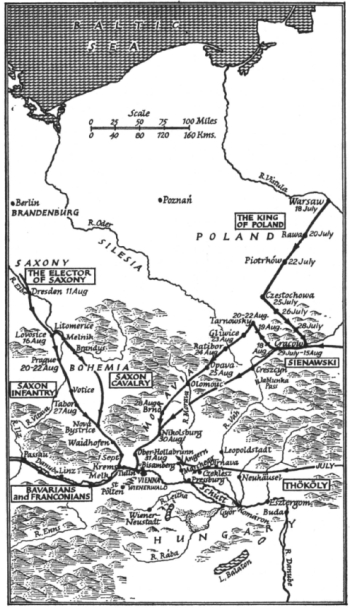

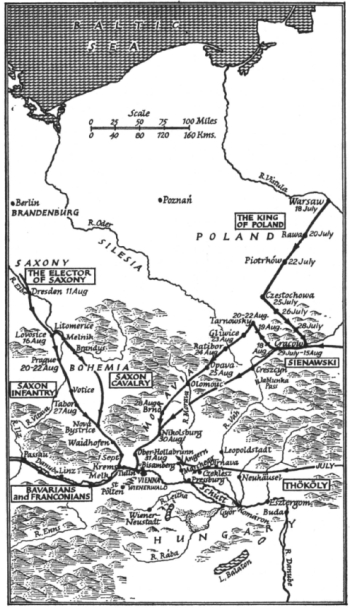

The King left Warsaw on 18 July and reached Cracow on the 29th.8 The whole court with the Queen, Prince Jacob, the Austrian ambassadors, the papal nuncio, and an incalculable number of servants, carriages and carts went forward at an average speed of seventeen or eighteen miles a day. It was not fast going, nor was the road through Piotrków and Czestochowa the most direct to Cracow. But Sobieski had to allow sufficient time for the mobilisation of his army. He had to visit Our Lady of Czestochowa, then and now the greatest shrine in Poland, to beg her good offices for the coming campaign. He had to defer to his assertive wife, who wished to accompany him and to go to Czestochowa and Cracow.

At this point of time, when the fateful venture was just beginning to gather momentum, one circumstance strikes an observer very forcibly. No single sensational report of a threatened catastrophe brought Sobieski to his feet, and made him ride from Warsaw to Vienna in order to honour his signature of a recent treaty. He was already preparing for the season’s campaigning, when Thurn arrived. Already he had been forced by stages to move troops away from the south-east, the theatre of all his earlier exploits against the Turks, to the south-west. At Wilanów on 15 July he first realised that the enemy was across the Rába in force, and concluded that Polish military power would have to be exerted somewhere in the triangle of ground between the points of Györ, Vienna and Cracow; but news of the Ottoman advance to Vienna, the city’s encirclement, and the state of siege involving the emergency clause in his treaty with Leopold, only reached him bit by bit. The distance from Warsaw to the Danube implied an equally disconcerting interval of time. Letters from Lorraine and Leopold to Sobieski were obsolete when they arrived, and his answers irrelevant. Then the gap narrowed. Vienna was ten days away at Warsaw, five at Cracow, and the news from Austria became clearer, fuller and more up to date. The King gradually elaborated in his mind a picture of the battlefield, drawn from the growing deposit of reports and dispatches which came in as he was riding south.

Piecemeal knowledge of the crisis hardly eased the strain which it imposed on the Poles. Their customary practice in the Turkish wars of the 1670’s had been the leisurely commencement in August or September of warfare which lasted until December, and was fought in Ruthenia, Podolia and the Ukraine with the manpower assembled there in the course of years. Men from the rest of Poland were moved south and east at a very slow pace, and the votes of a Diet to raise taxes and troops in one year often took effect in the next (or not at all). In any case an uneasy peace prevailed after 1676, and the Diet of 1677 insisted on a radical reduction of the army. In 1683 the machinery required for warfare on the grand scale was only just beginning to turn again, and no Polish politician would have been surprised if a serious attempt to recover Kamenets were delayed for twelve months. There was, of course, the unhappy possibility of a Turkish attack; but at least Poland had a military frontier in the southeast, with the ‘old’ army permanently stationed there. Yet now, as early as July, they had to visualise the immediate dispatch of an army to a point 200 miles beyond the south-western frontier of Poland. The decision to bring the ‘old’ troops to Cracow in fact signified that the ‘new’ regiments were not ready; and as Sobieski told Innocent XI in August, the authorities were only beginning to levy taxes for their pay.9 The chronic shortage of Polish men and money certainly accounts for his very great preoccupation with foreign subsidies10 and auxiliaries, but probably the worst feature of the crisis of 1683 was that it broke so early in the year. Nothing can have perplexed Sobieski more as he pondered affairs on his journey.

There is no sign that the King repented or was reluctant to push forward to Vienna, and without doubt it was the one course open to him. Not only did the treaty bind him, a treaty which accorded with his own judgment on the strategic question, but the tremendous political struggle in the Polish Diet a few months earlier absolutely committed him to his present course of action. His party in Poland would have collapsed overnight if he had hesitated to support his allies at home and abroad on this issue.

On 19 July after the second day’s advance from Warsaw, Sobieski wrote to the Elector of Brandenburg in his secretary’s roundest Latin. ‘Already the Ottoman fury is raging everywhere, attacking alas! the Christian princes with fire and sword . . .’ Fresh news had come in, because he now referred to Leopold’s flight from the threatened city. He announced the speedy concentration of all Polish troops at Cracow, and summoned the Elector to send an expeditionary force instantly.* The request went off to Frederick William’s ambassador at Warsaw, but within twenty-four hours a special messenger followed with further news: a letter from Lorraine had just arrived.11 This document, now lost, was the first instalment in a correspondence which has become one of the principal memorials of the time. Lorraine, it can be guessed, described how he was garrisoning Vienna with his infantry and placing his force of cavalry on the north bank of the Danube. A little later another letter reached the King. Its weightiest news was the withdrawal of the Habsburg troops under Schultz from the Váh valley.12

Replying to Lorraine on 22 July,13 the King recognises that ‘Vienna is really besieged by the Vezir’. Treaty obligations bound him to come to the rescue. He said that Vienna was more important to him than Cracow, Lvov and Warsaw—which meant, as always, that he preferred to defend these cities at the gates of Vienna. He was determined to overcome difficulties but complained that he had been left inexcusably ill-informed about conditions in Austria and Hungary. He asked for a detailed description of the Danube, its channels and islands; he obviously possessed no map of the Vienna landscape, nor did he even at this point specifically ask for one. He also criticised Lorraine for putting all his infantry into the city, thereby seriously weakening the army outside. He was all the more worried by this because his own infantry appeared dangerously inadequate. He hoped to use 4,000 Cossacks to cover the deficiency, and relied on the appearance of a strong Bavarian contingent of infantrymen. Further, he had not been told enough about the defences of the bridge or bridges which connected Vienna and its garrison with the field-army over the river. He recognised that the next bridge upstream, at Krems, might well prove of high military importance if Vienna were completely invested by the Turks, and Pressburg lost. But how strong, how large, was it? What was the character of the country (‘qui monies, quae planities, quae flumina, qui passus’) west of Vienna and south of the Danube?

To these queries, and a number of others, he expected full prompt answers. Meanwhile he was hurrying to Cracow, having placed detachments to guard the passes which lead from Hungary to south-west Poland and Silesia. He also asked Lorraine whether or not he should send Sienawski forward. By this offer, put in the form of a question, it looks a little as if he was delaying the Field Hetman’s march southward to the battle-field although he had previously agreed to it; but perhaps he hoped to conceal the awkward fact that Sienawski could not have reached even Cracow by the time of writing.

Two days later, on 24 July, the King spent the night at Kruszyna, a property of the Denhoff family, where the palace and gardens were admired by a French contemporary as outstanding of their kind in Poland.14 Here he wrote to his chancellor at Warsaw to inform him of the most recent news. A Polish officer had arrived with letters from Lubomirski and Lorraine describing the position at the bridgehead opposite Vienna.15 The Turks were in Leopoldstadt, he learnt, and the men of the garrison were cut off from the field army. Too few defence-works protected the Habsburg encampment and a sense of gloom filled Lorraine’s headquarters. The future depended, wrote Lubomirski (well knowing whom he addressed), on the King’s speed and strength even though the Germans also promised help. The day after he had given this account to his chancellor, Sobieski replied to Lorraine from Czestochowa. He would advance at once, without waiting for the full concentration of either the Polish or the Lithuanian forces. He had sent forward a vanguard; and Sienawski followed. He begged Lorraine to fortify his camp properly and promised to do everything in his own power to further the common cause. After signing this vigorous but somewhat vague exposition of his plans, he resumed the journey to Cracow.

By now Polish statesmen could hardly complain that they were not being given detailed information. The worse the state of affairs at Vienna, the more Lorraine wished to impress on them his profound sense of alarm. During the next few weeks he answered Sobieski’s queries and described what he had done to meet or anticipate his criticism. The bridge near Krems was strongly held, a new bridge to Tulln would soon be taken in hand. He reported the victory at Pressburg, praising to the sky the exploits of the Polish soldiers who fought there, and the march of the Saxons and Franconians from Germany. He forwarded copies of the letters received from Starhemberg and Caplirs in the city. He also sent a map of the theatre of war and this, on Sobieski’s instructions, was thoroughly scrutinised by the French engineer Dupont, who had hurried from the distant front near Kamenets to southern Poland.16 Lorraine, in fact, was doing his utmost to clarify the mind of the authorities in Cracow.

Two connected problems of great difficulty preoccupied the King. One was the mustering of his forces, the other the choice of a route to Vienna. At the end of June and the beginning of July, when the situation grew threatening in western Hungary, he naturally wanted to seal off the passes by which Thököly or Tartar raiders or even the Turks could enter Silesia and Poland, while he reckoned to leave responsibility for the defence of Moravia to Lorraine. This was probably still his view in the conferences held at Wilanów on 15 July. With definite news of the siege of Vienna it became more puzzling to know how to act. Troops moving from the area round Warsaw, or from the western Polish provinces, towards Vienna by the shortest route would pass through Czestochowa to Tarnowskie through Silesia and so southwards. The rational plan for the King would have been to advance straight to Silesia, while the ‘old’ army came up on his left, first to cover Cracow, and then taking the road via Cieszyn (Teschen) to join him. It was rational, but impossible. With only the ghost of an army ready in the west by the end of July, the King had to go himself to Cracow in order to meet the forces riding towards the same point from Podolia and Galicia. They, and they alone, could provide the solid core of an army fit to advance against the Turks and to claim pride of place among the other forces marching to relieve Vienna. The question of prestige profoundly affected the King’s dispositions: he could not afford to demean himself to the great dignitaries of Poland and Lithuania inside his own dominions, or to the Electors of the Empire who did not bear the title of King, or to the Habsburgs. Already his wife had seen fit to inform the court at Passau that her husband must be given the supreme command in the coming campaign.17 Great personal ambition, and a severe consideration of political and military interests, were linked firmly together. Whatever happened to Vienna, it was first necessary to bring together a sufficiently large army before moving out of Poland.

The King waited at Cracow from 29 July until 10 August.18 Pallavicini reports that troops came in almost daily. Field Hetman Sienawski arrived on 2 August, Crown Hetman Jablonowski on the 8th, the soldiers of both halted outside the city, and the King inspected them. Obviously very great efforts were made and a foreign eyewitness admitted the fact, testifying that ‘everything which occurred in this period of preparation for the war was a real miracle, considering the state of this country where fulfilment rather lags behind intentions’. Against such praise must be set Sobieski’s frank confession to Lorraine (on the 8th) that he would be leaving many troops behind, including the whole Lithuanian army and several thousand Cossacks. Nor did he allow any detailed specification of his force to be delivered to the Habsburg officials who would be responsible for quartering and provisioning the Polish army in Silesia and Moravia. The best calculation they could make put its size at 16,000 men, and this was somewhat higher than another estimate, of 13,000 or 14,000, given by Sobieski’s secretary in a letter to Rome as late as 18 August.19 But a Polish artillery officer states that Hetman Jablonowski’s force was small when it left Cracow, and increased in the course of the march; while there is other evidence that large numbers only came up considerably later. A Moravian record mentions Polish contingents passing through a particular place on the road to Vienna every day between 1 and 26 September—some of them, therefore, after the defeat of the Turks outside the city.20

On 22 July the King had offered to send Sienawski forward independently of the main army, and on the strength of this Lorraine wrote directly to the Hetman requesting him to advance with all possible speed. The King next informed Lorraine that a vanguard was already on its way to him, which would be followed by those under the Field Hetman’s command. But on the 10th he wrote that both contingents would wait near Olomouc for his own arrival—unless an emergency compelled Lorraine to ask them to move forward immediately. This delay occurred partly because the ‘old’ army did not get to Cracow until 2 August; partly (there is a suspiciously long interval between the 2nd and 10th) because the King was anxious not to lose touch with the Hetman by letting him move too far ahead. Polish military strength had not only to be sufficient; it was necessary for the King’s control to be as complete as possible. The more difficult it was to raise new troops, the more important it became to keep a firm hold on the older troops and their commanders.

The problem of the itinerary to be followed concerned not only Sobieski and the Poles but the population and administrators of Silesia, Moravia and Austria. The passage of a sizeable army through these lands was bound to add to the troubles of a country-side already heavily taxed for the war. Some areas and towns, if they were lucky, might hope to escape actual contact with the advancing soldiers. On the other hand, the commissariats of this period had found it a matter of common experience that the supplies and communications of any one region could not bear the strain of excessive numbers passing through, and they preferred to spread them out widely, in order to gather forage and food from as many places as possible. Considerations of this kind at first disposed the King, partly advised by the Habsburg government at Breslau, to plan a threefold line of advance to the Danube. Sobieski reserved for himself a line of march through Opava (Troppau) to Brno, while the left wing went via Cieszyn (Teschen), and Crown Hetman Jablonowski was to take a wide sweep through Tarnowskie to the right, possibly as far west as Bohemia.21 In the end Sobieski also went to Tarnowskie—the ‘general rendezvous’—but the Crown Hetman and the main body of troops accompanied him through Moravia to Vienna. The route via Cieszyn was still assigned to Sienawski.

The administrative reasons for spreading out the Polish forces, which would also have given the Hetman an independent command, were less urgent than the King’s need to lead his own troops. And he argued, as the authorities in Passau were arguing to Lorraine, that it was military madness to try to lift the siege of Vienna without employing the maximum force available. It turned out that the King’s calculations, and theirs, were correct by the barest possible margin.

During the long halt at Cracow, other pieces of news were recorded by observers. Sobieski sent an envoy to negotiate with Thököly,22 and his critics condemn this as obvious double-dealing; but the intention must have been to dissuade the Magyars from trying to raid into Poland during the King’s absence. Of greater popular interest was the celebration of St Laurence’s day (10 August) in the Cathedral. Amid a gathering of King, Queen, princes, bishops, generals, palatines, soldiers and people, the nuncio published the Pope’s indulgence for all men going out to battle in this Holy War. After hearing a powerful sermon on the same theme, the King moved down from his throne to the altar steps for the benediction, and was blessed by the nuncio. Pallavicini, writing afterwards to Innocent, recalled the singing, his sense of the King’s intense devotion, and the weeping of the Queen. The apostolic brief was translated, and thousands of copies were printed and published.23 The general enthusiasm ran high, enhanced by reports of Polish feats of arms under Lorraine and Lubomirski. It was time to go, and right to go, on the day of Our Lady’s Assumption the 15 August.

Sienawski had now hastened after his men, the forces under Jablonowski were on their way to Tarnowskie. The King and Queen with their household, and household troops, followed them up the Vistula valley and then turned north again. It took no less than five days to cover this stretch of country.24 Tarnowskie is thirty miles from Czestochowa, and the King of Poland had therefore spent twenty-five days in getting from one to the other. It must have seemed an eternity to the Austrian ambassador who accompanied him. But the King had at last collected his forces. A part of the ‘old’ troops first received their marching orders in Podolia, others on the Moldavian frontier: they rode 250 miles to reach Cracow. Many of the ‘new’ men came an equal distance from northern and central regions of the country. Only the Lithuanians and the Cossacks defaulted completely. Nor could there be any doubt of the King’s energy, and of his determination to play the most conspicuous part possible in a crisis which involved all his future prospects in Poland, and stirred up his military ambition and his Christian fervour. As it happened, for the last time in John Sobieski’s lifetime his physique was equal to a grand occasion. He was fifty-one years old in 1683, though already ailing too often, and far too fat.

On 19 August when the King was still some distance from Tarnowskie, General Caraffa arrived from Lorraine’s headquarters.25 He brought news of the greatest importance.

So far, information from Vienna emphasised that the relieving army must not dawdle, but sounded hopeful enough to suggest that there was still time to get such an army together. If there was not time, there was equally no point in exposing too weak a force too far from Poland itself. And the contemporary science of war tended to affirm that fortified cities with large garrisons did not fall quickly. And conditions in Poland slowed down the King’s advance. This sequence of facts and calculations acted together like a drag on the Polish military effort between mid-June and mid-August. The King had left Warsaw later than he originally intended. He left Cracow later than he said he would. He moved slowly even after leaving Cracow, and seemed increasingly preoccupied by political and military arguments for keeping all his forces together. This meant holding back the vanguard, and reducing the speed of his lighter troops. Lorraine’s plea, that Sienawski should go forward at once, met with a more and more guarded response. Hetman Jablonowski waited for the King. The King waited for the Queen, who appeared to dictate his speed by the pace of her own carriage. This could not go on indefinitely, and Caraffa came to clinch the view that it could not. He carried a letter from Lorraine of 15 August with copies of the first messages brought out of Vienna by Koltschitzky: the commandant Starhemberg was ill, Rimpler the chief engineer was dead, the garrison greatly weakened, the Turks were attaching their mines to one of the ravelins—‘I therefore beg your Majesty to come quickly, and in person with the foremost troops of your army, to assist us . . .” A similar appeal was addressed on two successive days to Hetman Jablonowski.26

Accompanied by Caraffa the King continued on his way to Tarnowskie. It was the rendezvous, and the first halt beyond the boundaries of old Poland. Final preparations were made, and a great review was held on the 22nd. One witness says that the Poles preferred to conceal from Caraffa their inadequate artillery and infantry by sending them on ahead.27 Another, the enterprising reporter who sent an account to the Breslau newsheet, Neu-Ankommender Kriegs-Curirer, described the splendour of the scene with 50,000 men, 6,000 wagons and twenty-eight cannon on the field.28 The first figure is incredible, the third sounds plausible. The King wrote once more to Lorraine and anticipated Caraffa’s criticisms of the army, which they had inspected together, by giving his own view: it was not large enough, but the daily arrival of old and new troops, and their extraordinary spirit, now encouraged him to go forward. After one more day’s march at the usual speed he himself proposed to advance with a picked body of fast troops.29

The King took an affectionate farewell of the Queen. She returned to Cracow to preside over the government of Poland, and this separation gave the King greater freedom of movement. It gave her that amazing series of letters, passionate and rhetorical, which he wrote in the course of his journey into Austria and Hungary.

The next few days were strenuous enough for the moving forces of men, and the districts through which they passed. The King spent the nights of the 22nd and 23rd in monastic houses. Crossing the Oder at Ratibor he was well entertained there by the Obersdorf family at the Emperor’s expense.30 His reception in Silesia satisfied the King, and provisioning for his army seems to have been adequate. The Habsburg administration gave the lightweight Polish coinage a limited legal currency, but naturally made every effort to keep the troops outside the towns; the quartermasters and commissaries were continually busy.31 The Estates of nobility paid deferential attention to the King and the Polish grandees. At the same time the wheels of diplomacy went on turning. The King wrote to the Queen on the 23rd and 25th, to the Pope on the 23rd, to Lorraine on the 24th. News came in from Danzig, Paris, Lorraine’s camp, and Cracow. With some 3,000 men the King definitely went ahead of the main army after the 24th, and on the next day hurried through Opava without loss of time. He went up into the hills along a steep and stony road. On the evening of the 25th, he was handed official messages of welcome from Leopold and his court. But King John describes these as ‘impertinent’ to his Marysienka; while at Olomouc the next night he was displeased equally by his lodgings and the character of the citizens. He slept under canvas for the first time on the 27th, and by the next evening reached a small town not far from Brno.

The news coming in from the south was bad. Lorraine was getting desperate about the situation in Vienna; correspondence with the garrison increased his fears. On the 21st he forwarded Starhemberg’s letter of the 19th to the King and—the direct evidence has been lost—he must once again have appealed to Sienawski, who had advanced through Silesia and Moravia on Sobieski’s left. There is no sure proof of the date when the King first read Starhemberg’s letter but on the 25th he was highly alarmed by what he had learnt of Lorraine’s new request to Sienawski, a request backed by Lubomirski. He did not want Lorraine to try to relieve the city before he arrived, nor did he want Lubomirski or his Field Hetman Sienawski to risk the terrible penalties of defeat by employing too small a force of men. Above all he did not want his personal prestige compromised. As he said: ‘Precipitate action might cause disaster (which God forfend), or give to others the glory of forcing the enemy to retreat before I arrive, and therefore I am hurrying forward, having strictly commanded the Hetman to wait for me.32 With this crucial problem on his mind, it is hardly surprising that the ceremonial harangues and the salvoes of municipal artillery at Olomouc did not appeal to him.

On the 27th he received a letter written by Lorraine two days earlier. Addressed to Sienawski, it contained a positive proposal for a meeting between the Austrian commander and the Hetman at Wolkersdorf (a long way down towards the Danube) on that very day, the 27th. In accordance with the King’s previous instructions, this meeting could not and did not take place. Lorraine drew back to Korneuburg where there was enough to preoccupy him: guarding the area from which Thököly’s men and the Turks had recently been driven, destroying the Vienna bridges which the Turks were trying to mend, and finishing the new bridge at Tulln.33 The King moved on, hurrying but not to be hustled. He informed Lorraine on the 28th that he must wait for the troops behind him, while ordering Jablonowski to bring forward his cavalry and leave the infantry to follow. He received in audience one of the Liechtenstein family, proprietor of much of the neighbouring land. At Brno he dined with old Kolowrat, Lieutenant of Moravia. He admired the city, the citadel of the Spielberg above it, and the country-side round about which looked rich with the harvest—‘better land than the Ukraine’, he wrote. He camped late that evening, signing his letters long after dusk. There was much to occupy his thoughts. A copy of Starhemberg’s most recent appeal had arrived. So had Lubomirski in person, to give him first-hand impressions of the scene of war, and of the Habsburg leaders. But there was nothing from Poland. Had the Queen reached Cracow? Where were those Cossacks and Lithuanians, after all the money spent on them? Or, looking south once more, why was the bridge at Tulln not ready yet? Should he lead his troops to Tulln, or Krems, or elsewhere? He now (on the 29th) asked for a conference with Lorraine as soon as possible.34 Next day his troops began to cross the River Thaya, the Austrian frontier. Hilly country lay to the left where his men were trying to establish contact with Sienawski’s detachments. Next day again they started at dawn, in clear cloudless weather, following a route south and westwards. Soon after noon Sienawski appeared on the road, and Lorraine shortly afterwards. The Duke, once a candidate for the Polish throne, and the King of Poland had met at last. They rode on to Ober-Hollabrun together where they found Waldeck, commander of the Franconian troops already camped on the other bank of the Danube, and various high-ranking officers. There were introductions, inspections, toasts and preliminary consultations. All the witnesses differ as to the details; all were aware that this was a significant occasion, and not only in the history of an Austrian village.

In 1683, so far, most men had discussed the great crisis of the day from a distance. Vienna was remote, beleaguered, and they pondered its probable fate in courts and townships between Madrid and Podolia. They continued to do so, but the meeting at Hollabrun signified that the Habsburg government was at length fusing together widely dispersed forces into a combined armament capable of relieving the city. When Sobieski and Lorraine and Waldeck met, it was as if the curtains had been pulled back, though only by an inch or two and for a moment, to disclose the possibility of an astonishing and decisive feat of arms. The Danube, the hills of the Wiener Wald, and the numbers of the enemy, had always appeared formidable obstacles to success. On closer inspection they still looked formidable, and yet it seemed possible to overcome and even to profit from them.

* The Elector’s obligation to send help to Poland was a relic, confirmed by treaty, of the old feudal dependency of East Prussia on the Kingdom of Poland which ended in 1657.

One other powerful force, from Saxony, had also been brought into the arena by this date.

Leopold’s ministers, when the Sultan’s army entered Hungary, sent Lamberg once more to John George in Dresden and to Frederick William in Berlin. They continued to think in terms of the defence of the Empire, but hoped that a satisfactory agreement with the greater German princes would free more Habsburg troops to deal with the Ottoman advance. A fresh negotiation began in Dresden, but was soon overshadowed by the Elector’s dispute with his Estates. They refused to pay for his increasingly numerous standing army, while he insisted on larger grants of supply. Then the dreadful news from Vienna reached them, to be followed hot-foot by Lorraine’s special envoy the Duke of Sachsen-Lauenburg, appealing for immediate aid.35

John George’s military ardour was at once fired by the prospect of a catastrophe which his initiative might help to avert. He had in any case to face the threatening implications of a permanent Ottoman encampment within striking distance of the routes northwards from Moravia and Austria. But he also argued like his neighbours in Franconia:36 it happened that at the moment he was maintaining numerous troops ready for action; that his own subjects objected strongly to the cost; and that the Turkish assault on Austria made their employment in the Empire unlikely because the Empire would have to acquiesce in a peace dictated by France. If, and the if was important, the Habsburg lands paid the costs, an expedition to Vienna looked like the reasonable temporary solution of a serious problem.37 The crisis of 1683 in fact forced the Dresden government to use a tactic which was popular enough in the early history of German standing armies. In the next few years Saxon and Brandenburg and Hanoverian regiments, dispensable at home, would be hired out to fight for the Habsburgs in Hungary or for Venice in the Morea. These arrangements were often the result of the most exact and bitter bargaining; but John George proved on this occasion a somewhat careless politician.

He had taken his decision by 22 July without insisting on precise agreements about supply, or the command of his forces in the field. Sachsen-Lauenburg assured him that the Habsburg government was certain to satisfy him on the first point; the Elector vaguely felt that the second could cause little trouble because he himself was setting out at the head of his army. Lamberg wrote from Berlin to lay that he intended to come back immediately to Dresden, in order to complete detailed arrangements for the line of march through Bohemia, and the provisioning of the Saxon regiments. The Elector still had qualms that Frederick William of Brandenburg would secure more favourable terms from Leopold, and he therefore instructed his envoy Schutt to negotiate with the Habsburg statesmen at Passau. Schutt was to ask for the army’s pay and supply on the march and during the campaign, for winter quarters, and also for a solution of current frontier disputes affecting forestlands claimed by both Bohemia and Saxon mining enterprises; if possible, Saxony wanted territorial concessions. It sounded grasping enough, but all these requests were robbed of their menace by John George’s prior decision to go to Vienna.

This was the position on the last day of July, and the Elector left Dresden on 11th August.38 The bustle in and about the city was tremendous. On 4th, 5th and 6th, some 7,000 infantry and 3,250 horse and dragoons were mustered on a great meadow by the banks of the Elbe, to be ceremonially reviewed by John George on 7 August. A first-class artillery officer and expert on fortifications, Caspar Klengel, selected artillery from the Dresden arsenal: 16 guns, 2 petards, 87 carts, 351 horses and 187 men were inspected on the 10th. The Elector’s own household and staff, when the expedition set out, amounted to 344 persons. Meanwhile members of the Saxon Diet produced a final catalogue of their doubts, debts, and grievances, in a not so humble petition. Commissaries of the Saxon and Bohemian governments met in conference, they settled how fast the army should march and how often it should rest. The Saxons undertook to cross the Bohemian frontier on 13 August and the Austrians agreed in rather airy and imprecise terms to find the supplies which would be required in Bohemia.

The Saxon soldiers now began to move southwards. It was at once apparent that communications and commissariat were entirely inadequate in their own country. They must have put to one another the question, were conditions likely to improve across the border in Bohemia?

A bare recital of dates in the month of August, and of places passed, seems to record the steady progress of the expeditionary force.39 It went over the heights to Teplice, and reached Lovosice by 16 August. Here it divided into two main bodies. Most of the cavalry moved up the Elbe valley, crossed to the right bank of the tributary Ultava (the Moldau) and then rode over the plains east of Prague, arriving in the uplands of southern Bohemia by the last day of the month. Meanwhile, the infantry and the Elector himself reached Prague on the 20th, followed the obvious southerly route to Tabor, turned south-east, and joined the cavalry in the neighbourhood of Nová Bystrice. They were now half-way between Prague and Vienna.

This record is deceptive. Only feverish negotiation, and hard riding by the negotiators, kept the army moving forward. On the day John George entered Bohemia, and on the next day when he rode to Teplice, a whole sequence of envoys reached his headquarters: the tireless Lamberg still shuttling between Brandenburg, Saxony and Passau; the Bohemian commissioners, who now announced that they were not empowered to provide supplies gratis to the Saxon troops; and a messenger from Schutt, to state that his discussions at Passau had not led to an agreement. Indeed the Habsburg ministers turned down every one of John George’s demands: for winter quarters, supplies, the supreme command in the field, and territorial concessions of any kind. They simply continued to ask blandly for his help and of course, from their standpoint, they correctly assumed that the Elector would find it difficult to draw back. The Saxon counsellors conferred angrily at Teplice. The diary of one of the most influential, Bose, says that the case was argued for an immediate return to Dresden.40 Lamberg intervened, pleaded, and finally secured a fresh statement of Saxon grievances with which he hurried off to Passau. The Elector said that he was determined not to advance beyond Prague until he received a satisfactory answer. The paper in Lamberg’s hand repeated his original demands, but the envoy himself now saw that only one point was crucial: if the Habsburg ministers wanted the Saxon army, they must at least co-operate in finding the necessary food and forage; nor could the Saxons be expected to pay for these. The other demands could be evaded, as before, by sensible diplomatic inaction. The army moved on. The Elector delayed a few hours longer to enjoy the hunting and to admire the scenery.

What happened in Teplice happened in Prague. Schutt’s message had been followed at a slower pace by a polite letter from Leopold, echoing the negative response of his councillors. The reply to the Saxon ultimatum carried by Lamberg had not yet come in. Once again the Elector sent off a messenger, Friessen, who was to state that the Elector proposed to advance no farther than two days’ march beyond Prague unless he got a satisfactory answer. Prague, so the diarists report, was an enjoyable city, the entertainment given in the Duke of Sachsen-Lauenburg’s palace was excellent; the Elector went sightseeing but, once again, he finally moved forward on 22 August without waiting for Leopold’s reply.

He was still trying hard to find more money at home. He required his administration in Dresden to raise a loan of 200,000 thaler; they said, dryly, that it was out of the question. He required the Estates of Upper Lusatia to find him 30,000 thaler.41 In both cases he wanted actual currency, his great need of the moment, not credit. Household economies at the Dresden court were also discussed; but there is no evidence that any of the suggestions provided extra money. The Saxon army simply continued to take from the rural population what it needed to keep moving. Payment was no doubt the exception rather than the rule, and no doubt the requisitioning of enough supplies for 10,000 men looked a hopeless business on the mountainous threshold of Bohemia round Teplice. But a week later in the central plain, just after the harvest, it was easier. For this reason, the threat to withdraw became less and less pointed; and John George knew that while the Elector of Brandenburg still held back, the Elector of Bavaria and the King of Poland were hurrying forward to take part in what might prove a glorious and exciting crusade. He and his officers were now near enough the Danube to smell battle.

Farther to the east, the cavalry continued to advance. The men and baggage of the infantry and artillery, with the Elector’s staff, passed through Votice and got to Tabor on 27 August. At both towns, soothing assurances came in from the court at Passau. Leopold accepted the Saxon demand for the free consignment of supplies during the march through Habsburg territory to the theatre of war. He also offered supplies for the coming campaign, provided that these could ultimately be charged to the account of the Saxon government. He left John George in full command of his troops, though reserving his own ultimate authority and the possible claims of the King of Poland. In general terms he accepted the principle that the Saxons could claim winter quarters in Habsburg territory, if these should be judged necessary; but said not a word about an adjustment of the northern frontier in the Elector’s favour. Bose, in his entry for 25 August, noted that ‘the whole court expressed itself satisfied’, and it seems as if the Habsburg assurances were just generous enough at a moment of crisis to silence John George’s more exacting councillors. At Votice, also, another diarist recorded items of news beneath the notice of serious politicians: the 26th was a heavy thunderous day, four musketeers were court-martialled for plundering, and one was executed.42

Not long afterwards the two parts of the Saxon army began to knit together again. From Nová Bystrice Bose and Flemming were sent to the Emperor, now at Linz. The Saxons started crossing into Austria on the day that John Sobieski and Lorraine entered Ober-Hollabrun fifty miles east of them. They marched steadily forward, through Waidhofen which belonged to Lamberg’s family, and through Horn which belonged to Count Hoya. The troops camped in the open, and the Elector quartered comfortably in the residences of these great landlords; from the windows of the palace at Horn it was possible to survey the whole encampment of the Saxon army on 2 September. On the 3rd the men rested, and then made their way to the Danube. They reached Krems on 6 September. The last few days had passed without incident, although there was considerable nervousness about the alleged marauding of the Poles, with whom the Saxons were coming into contact for the first time. For one night most of John George’s regiments quartered on an island in the stream of the Danube. The Bavarians and Franconians were already over on the right bank of the river. The Poles were coming up on the left, farther downstream. The Saxons, in fact, now merged into the large and rapidly expanding army of relief, one of its best organised contingents.

Against this outstanding diplomatic success, the Emperor Leopold’s advisers had to set the total failure of their approaches to Frederick William of Brandenburg. Certainly, the Habsburg interest had its champions in Berlin. The Elector was too good a politician to let Rébenac, the tireless French envoy, have everything his own way, and Lamberg’s many visits served to remind Louis XIV that Frederick William never lost sight of the working alternative to his general policy (in these years) of partnership with France. If Fuchs and Meinders, industrious officials, were for the time being content to favour French interests and to accept modest French gifts of cash when offered,43 Prince John George of Anhalt-Dessau was a very different proposition. Wealthy, aristocratic, with a princess of the house of Orange for his wife and normally resident in Berlin, he could afford to play the part of the Elector’s life-long friend, unruffled by the Elector’s famous tantrums; and throughout 1683 he acted as an enthusiastic supporter of the Habsburgs. Derfflinger, Austrian by birth, perhaps the Elector’s favourite military commander, and the Electoral Prince Frederick, both stood by him. They all felt that Brandenburg ought to share in the common duty of states of the Empire, the defence of Emperor and Empire against aggressors. They urged, plausibly enough, that a Turkish thrust from Hungary towards Moravia and Silesia might come dangerously close to Brandenburg territory. They reminded the Elector of his claim by inheritance on some of the Silesian duchies. Yet they failed to assist Leopold at a time when their argument sounded strongest.

June and July 1683 were shocking months in the annals of the Hohenzollern court. It was learnt that Louis XIV had refused to ratify a draft agreement, by the terms of which French troops would have held the Brunswick princes in check while Brandenburg (with Denmark) invaded Swedish territory in north Germany.44 The Elector’s sister and daughter-in-law both died; the Elector himself was troubled by the stone and the gout, and fell seriously ill. The doctors despaired of him, but he gradually recovered. His mood of irritation with the King of France was such that Rébenac found, temporarily, that the critics of France at court were in the ascendant. In June the Elector welcomed, with considerable courtesy, another short visit by Lamberg. Anhalt was optimistic about the prospect of an alliance with the Habsburg court.45

On 7 July, shortly before he hurried away from Vienna, Leopold wrote to Lamberg at Dresden: the enemy was at the gates, and he must go at once to Berlin and ask for help. In consequence, from the moment of the envoy’s arrival on 16 July, the Elector’s household in Berlin and Potsdam became a centre of intense discussion and intrigue. Frederick William was at first too ill to see Lamberg, who asked for the dispatch of 6,000 men to Vienna and offered 200,000 thaler for them. Fuchs replied politely that neither figure was satisfactory. The Elector would require at least 300,000 thaler for 6,000 men, and in any case he was convinced that an expeditionary force of 12,000 was needed in so grand an emergency.46 In his own mind, of course, the minister had to try and calculate whether a more or less substantial part of the army which had been intended for the campaign against Sweden, with the help of a French subsidy, could be transferred to Habsburg territory and maintained by Habsburg funds. He reminded Lamberg that the Elector expected the Emperor to come to terms with Louis XIV, but closed the discussion with two promising items of news. Anhalt was to go at once to Leopold’s court. Derfflinger was to take charge of the military preparations.

On the 23rd, Anhalt left Berlin. Whatever the exact tenor of his instructions, he told Lamberg, he was determined to negotiate in the Emperor’s favour. With an envoy so curiously insubordinate, the possibility of a misunderstanding was a very real one. To make matters worse Rébenac, writing an 28 July, was able to assure Louis XIV that ‘the Prince will find his instructions quite different from what he thought they would be when he left.’47 Indeed, the Elector’s standpoint fluctuated. He lamented the weakness of the Christian states in the face of a violent Turkish attack; but he was swayed by the fact that later news from Vienna was less catastrophic than the first reports. Rébenac, in a long private interview, emphasised with eloquence and skill all the arguments against sending the Brandenburg troops too far afield; it soon became clear, for example, that the Brunswick troops would remain in north Germany. The Elector began again to recollect that French subsidies were punctually paid, to appreciate that his major interests were focused in this northern area between the Vistula and Rhine. Unless he squeezed very substantial concessions from the court at Passau, the case against helping the Emperor was not as weighty as the case for keeping him weak. Almost from hour to hour the Elector tacked and tacked, without in the end altering the general course of his diplomacy. On 22 July he agreed to send a mere 1,200 men to aid Sobieski in accordance with old treaty obligations.48 He sent a message to tell Anhalt that some 15,000 were assembling at Crossen on the Silesian border, but repeated to his envoy that a pacification in Germany must precede any military pact with Leopold. If old Derfflinger still felt hopeful of sharing the glories of a campaign against the Turks, Rébenac, steadily writing his dispatches to Louis XIV from Berlin, was confident that the Elector would stand firm in the French interest. Frederick William, he believed, had recovered his balance. The French envoy, not the Austrian soldier of fortune, was right.

Anhalt duly arrived at Passau with an impressive staff of servants and followers, and presented his proposals on Saturday, 7 August: peace must be made with France, the Elector offers 6,000 troops, he asks for their supply during the campaign, and lists a variety of financial demands which amount to a total of 500,000 thaler to be paid by Leopold.49 An agreement could be worked out in three days, he concluded, a courier to Berlin needed five days more and at once the Elector’s regiments would commence their march to the Danube. Königsegg, Stratmann and Zinzendorf, conferring together on the Sunday, did not share this rosy view of the immediate future. They found the Brandenburg demands unreasonable, requiring sums of money utterly beyond Leopold’s capacity to pay. They disliked the suggestion that ‘assignments’ of the revenues of various principalities in the Empire should be made over to Brandenburg by the Emperor’s fiat. They refused to admit the Elector’s claim to the Silesian duchy of Jägerndorf, which he was now apparently willing to trade in return for a huge monetary compensation—200,000 thaler, equal to the whole amount recently granted to Poland. Above all, in the Elector’s proposals there was no hint that Brandenburg intended to join the Habsburg system of alliances in the Empire in order to resist France, even supposing that his troops took part in the war against the Sultan. And if those troops were forthcoming, they would surely arrive too late to help in the relief of Vienna: instead, they would arrive in time to demand winter-quarters on Habsburg territory. Having listed all these objections, Leopold’s ministers solemnly decided to continue the discussions with Anhalt. It is possible that they realised the envoy’s own determination to come to terms, and overestimated his influence at Berlin. They had in mind one further point. If Vienna fell to the Turks in September, an outright rejection of Frederick William’s offer in August would have turned out unnecessary folly.

The second week of August in Passau, therefore, was partially taken up with conversations between Königsegg, Stratmann, and Anhalt. The debate can be reconstructed. One document, with comments added by Anhalt, shows Frederick William’s demand for a settlement with France watered down to the plan of a personal interview between Leopold and the Elector, to take place in the following October at Regensburg to discuss such a settlement. The Brandenburg troops must join the Habsburg army before the end of the first week in September. The question of Jägerndorf, or of any financial equivalent for it, was to be left over until the close of the Turkish war. Anhalt then gave even more away. Certain it ‘puncta foederis Caesareo-Brandenburgici’ were drawn up.50 In this extraordinary draft, the final article visualised a common effort to undo the ‘reunions’ of imperial territory to France, after the Turks had been repulsed with the aid of 12,000 Brandenburg soldiers. Not surprisingly, in Königsegg’s lodging on Friday 13 August, the Austrian ministers reported to the Dutch and Swedish and Hanoverian representatives that they had been hard at work on a treaty with Frederick William.51 On paper, at least, they had scored a real diplomatic triumph; and a courier set out for Berlin. Further progress in that quarter could hardly be expected within the next ten days.

The ministers turned, perhaps wearily, to deal with another problem.

Their immediate and essential duty was to take all possible steps to rescue Vienna, but their fundamental responsibility remained the defence of Habsburg interests as a whole. And these interests still required, in their judgment, a stubborn championship of Leopold’s position in Germany. When Louis XIV’s ambassador, Verjus, made a new offer to the Estates of the Empire at Regensburg on 26 July, the statesmen at Passau had to consider their reply.

The French proposal, accompanied by the sharpest invective against the Austrian and Spanish Habsburgs and their allies—who had neglected to defend Europe against the Sultan in order to intrigue shamefully against Louis—was that both the King of France and the Empire should publicly recognise the status quo in the Rhineland for a period of thirty years, leaving undecided the legal problem of ultimate sovereignty in the territories which the French had occupied since 1679. The King would not ask for the compensation to which he was entitled; and the offer stood open until 31 August.52 In other words, Louis and Louvois had determined not to intervene in the Empire for one more month; and during that month Turkish pressure, and the pressure of the German states friendly to France, and indeed of all those interests which genuinely believed that a settlement with France was the pre-condition of any effective action against the Ottoman power, were to squeeze from Leopold a significant gesture of surrender. In Regensburg the French knew that all the Rhineland Electors—Cologne, Mainz, Trier and the Palatine—were their allies, while the Brandenburg representative, Gottfried Jena,53 never wavered from the Francophile line of policy unreservedly followed by Frederick William in the Diet. In fact, they could rely on the College of Electors. Were Leopold’s ministers, expelled from Vienna, strong enough to resist Kara Mustafa, Louis XIV, and at least five of the Electors?

Stratmann and Königsegg were tough and intelligent statesmen. Their immediate aim was to collect forces for the relief of the city within two months. They had no use for concessions which did not strengthen the Emperor at once; resistance to France had been their great watchword in politics for years, their permanent assignment; and they were by now sceptical of these French time-limits which, so often renewed, had lost something of their original menace.54 But they had to meet strong resistance from their friends. At Regensburg, Bavarian and Saxon diplomacy was less sympathetic to Leopold than in Vienna or Passau; and at Passau itself, a number of people close to the Emperor certainly wanted the French offer taken up without further delay. For them, it seemed obvious that there was no time to lose. On the other flank, the Dutch and Spanish envoys were justifiably alarmed, because if the French offer was indeed accepted, Louis XIV could not in future employ his armies in Germany, and would be likely to throw his whole weight against the Spanish Netherlands. As a result, these two diplomats weighed into the grand debate with all their skill.55 They wanted the absolute rejection of the French proposal for a truce unless Louis explicitly agreed that it included lands in dispute outside the Empire—by which they meant Luxembourg* and the rest of the Spanish Netherlands. The Austrians, for their part, did not at first wish to rule out the chance of coming to terms with Louis if the worst should befall, and Vienna fell. The Dutchman, Brunincx, realised that they would then pay little or no attention to the interest of their allies in the north. This conflict made it difficult, in the first few weeks at Passau, to formulate a common policy; and the debate continued in the course of many discussions. Early in August the Habsburg tactics were tentative, almost negative. Windischgrätz, the Imperial commissary at Regensburg, the ‘mad Roland’ who aroused the passionate dislike of Verjus and Gottfried Jena,56 was instructed to brush aside the time-limit for the moment, and to inform the Diet of Leopold’s intention to go himself to Regensburg in October in order to confer personally with the Electors and Princes on all matters of common interest. This was the project which had been raised in the parallel negotiations with Anhalt. Then more hopeful news reached the government from Vienna, and Waldeck also arrived at Passau, after arranging for the Franconian troops to follow him down the Danube.57 It is clear that he gave powerful assistance to all those who meant to give nothing away to the French because they were confident that the Turks could also be repulsed. Another plea from the four Rhineland Electors, dated 21 August, was set aside in a firm reply from Leopold on the 23rd. His ministers had at length decided on their policy. They were not prepared to respond to the French offer before the time-limit expired on 31 August; and they were not prepared to say that it was acceptable provided that territories outside western Germany were included in the truce. This was much less negative than it may sound on a casual reading. Leopold had given nothing away to Louis XIV, and very little to the Spaniards and the Dutch, at a time when the pressure on him to do so was greatest.

On 24 August Waldeck wrote to William of Orange.58 He was happy enough to report his own part in the strenuous discussions of the past week. The Emperor, he says, declared in conference that he would rather lose some of his lands than make a truce with Louis; but Waldeck believed that Louis was unlikely to ‘insult’ Leopold for the moment. His personal views on the Danubian theatre of war were simple and outspoken: the Habsburg government should never have left Vienna; the city would continue to hold out until it was relieved.

Anhalt’s draft-treaty, when it reached Berlin, caused immense annoyance—and Rébenac was delighted. Frederick William replied at once, rebuked Anhalt for exceeding his instructions and recalled him. The Austrian ministers, by now in Linz, sadly concluded that they must write off their hopes of employing Derfflinger and 6,000 or 12,000 Brandenburg soldiers in the coming struggle for Vienna. They did however decide to pursue negotiations with Anhalt, who had himself determined to remain by the Danube and, if possible, take some share in the campaign ahead. He told the Austrians that he knew the Elector’s temper: the last dispatch from Berlin was no doubt the product of insomnia and irritability; if the more militant clauses of the draft could be toned down, he hoped to convince the Elector of its value. On 1 September Stratmann and Königsegg still judged it worthwhile spending their valuable time discussing Habsburg relations with the Hohenzollern court. In retrospect their labour seems an unnecessary use of ink and energy. They had done what they could to mobilise the states of Europe; the troops had already marched out of Germany and Poland, already reached the Danube close to Vienna and the Ottoman besiegers. The months of diplomatic preparation in distant courts were over. Lorraine, Kara Mustafa and Sobieski, acting for the moment as soldiers rather than politicians, would have to shape the immediate future.

* Although Louis gave up his blockade of Luxembourg in April, 1682 (see pp. 52–3), it was obvious that he still hoped to win this great citadel by one method or another. Earlier in 1683 he made an ‘offer’ for it to the Spaniards, but here again his time-limit had run out by July.