LOWELL NAEVE

Raised in Sioux City, Iowa, Lowell Naeve (1917–2014) left home a year or so after high school, traveling to Los Angeles, Mexico City, and finally New York, and picking up odd jobs along the way to pay for art classes. In New York he met his future wife Virginia Paccassi, also an aspiring artist, and ran into trouble with his draft board. A free spirit prompted by personal conscience rather than any particular faith or ideology, he was deeply opposed to military conscription, and so spent most of 1941–46 behind bars: first in New York’s West Street Detention Center, then in Danbury Federal Penitentiary, then back again in both prisons. A Field of Broken Stones (1950), his illustrated memoir of these years, was smuggled out of the latter institution in a hollow picture frame.

In the short excerpt reprinted below, Naeve describes a typical day in West Street—where one fellow prisoner was the gangster Louis “Lepke” Buchalter—around June 1941. The small act of resistance to authority it describes was the first of many. (It was probably Naeve—and not the “fire-breathing Catholic C.O.” Robert Lowell, as has usually been reported—who responded to Lepke’s question “I’m in for killing. What are you in for?” with a line now legendary in the antiwar community: “Oh, I’m in for refusing to kill.”)

After his release, Naeve worked as a woodcut artist, art teacher, and filmmaker, and owned a dog kennel; he published a collection of drawings, Phantasies of a Prisoner, in 1958. In 1965 he emigrated to Canada with his family, encouraging Vietnam-era “draft dodgers” to follow him rather than suffer in prison as he had. He died in Creston, British Columbia, at the age of ninety-seven.

FROM

A Field of Broken Stones

THE day in West Street began, it seemed to me, when I came up from work in the officers’ mess. It would be about ten in the morning. I’d see Hymie Weiss, one of Lepke’s partners in Murder, Inc., enter the elevator with an escort of four guards. There was a desperateness about the way they would get the elevator all ready, take him out of his cage, put him on the elevator, and take him to the roof for exercise.

Weiss would be up on the roof for an hour, then they’d bring him back. After they had locked him up, they’d get the elevator ready again, escort the big boss Lepke out, take him to the roof for an hour. And so it went every day. . . .

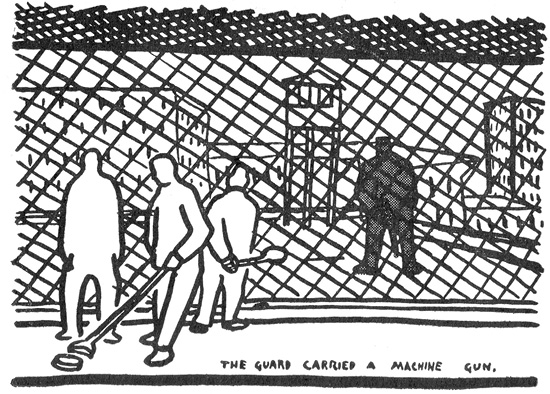

The rest of us were given an hour and a half of exercise together. The “roof” of West Street was very small, about seventy-five by twenty-five feet. It was caged up on the sides and top with heavy steel mesh. Inside of the cage we took our exercise. Beside the exercise enclosure was an open part of the roof. On this stood a short guard-tower with steps leading up to it. Between the tower and the cage was a wooden boardwalk. When not in the tower, the guard sometimes stood on the boardwalk. He carried a machine-gun.

Inside the cage there were two ping-pong tables, a shuffleboard court, etc., but there was little room to do anything. Most of the men just sat, lifted their faces to the sun, and talked; some paced up and down, worried about their coming trials.

After exercise period I had to go to work in the officers’ mess again.

. . . While working in the officers’ mess, waiting on the warden, the captain, and the guards, I became disgusted with myself for submitting to being ordered around. I did not like the idea of being forced to do things I didn’t want to do. But I said nothing, I only did like everyone else, kept still, grumbled to myself.

On the fourth day, to bolster my sinking morale, I decided to practice a little “equality.” I picked up a piece of Officer Pie, took a glass of Officer Milk, and just outside the officers’ mess, in full view, began to drink the milk and eat the pie.

The night captain, a large surly-tongued individual about to receive his pension, was standing nearby. He watched me raise the pie to my mouth. He looked at the pie, looked a little more—Christ, what a big piece! He was about to yell. He couldn’t accuse me of stealing. I turned slowly to look at him, then returned to eating the pie. He paused, half turned, hesitated again, then strode down the passageway.

After supper, when work was over in the officers’ mess, I would go up to my cell block and talk with some of the other prisoners, or draw on some typing paper I had managed to obtain.

After the guards took the ten o’clock count and turned out the lights, I would frequently stay up, talk to the other prisoners. It being June, the jail was usually so hot we couldn’t get to sleep till after midnight.

The conversations in our cell block centered around a fellow named Bard—he was a shakedown artist, broad-shouldered—a short Charles Atlas. In the cell block were two or three others who had made a living off of “this dame” and “that dame.”

“I was in Atlantic City,” one would say, “and I met this rich broad. . . . I’m telling you, man, this woman was a bitch, really a bitch.” And then he’d tell his story. . . . After he had finished, another would tell about a “broad” in St. Louis. He would, so he’d say, do this and that to her—“What a lay!” . . . Bard hardly ever spoke, but it all centered around him. The lesser shakedown artists looked up to him; it was rumored he was married to a burlesque queen. The others thought he knew all the tricks. All hung around, hoping he would let them in on some new secret.

There was talk till the place cooled off a little, then we went to our bunks.

At night, the bars were most impressive. By day West Street Jail was, more than anything else, a pressing din, a place of perpetual noise. The sounds of the place were dominated by the loudspeakers above us. They all blatted out the same tunes. Occasionally a microphone announcement from the “front desk” broke into the barrage of music.

Within the din could be heard the swishing of mops, the sliding of mop buckets, the sound of steel gates slamming shut, the sound of keys turning locks. We could hear guards barking out orders, their many keys going clink clink clink as they walked along.

But above it all—grind-ing-ly blar-ing-ly—the loudspeakers droned on. They dominated the place, smothered to a hum all other sounds.