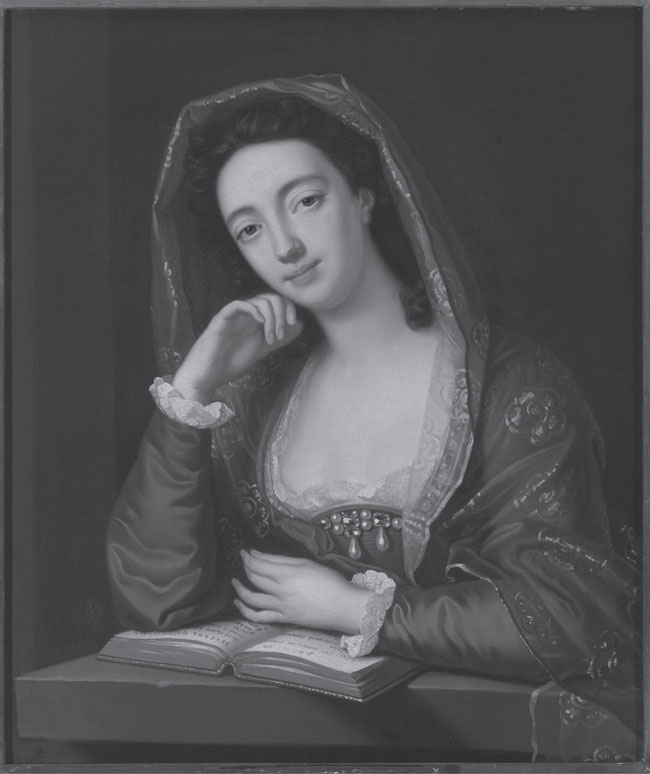

FIGURE 2.1 Portrait of Margaret (Peg) Woffington, by an unknown artist.

Courtesy of the Garrick Club, London

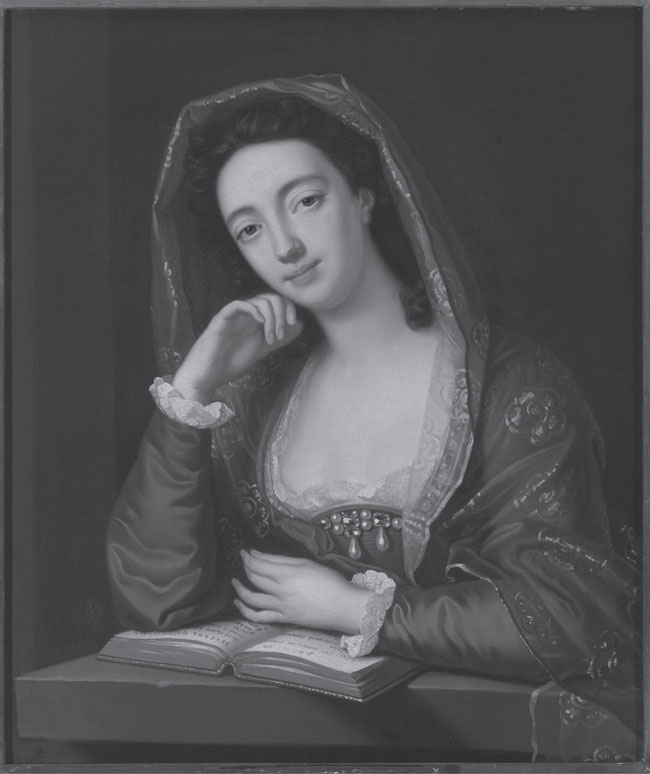

FIGURE 2.1 Portrait of Margaret (Peg) Woffington, by an unknown artist.

Courtesy of the Garrick Club, London

She first steals your heart and then laughs at you as secure of your applause

(Anonymous)

Margaret Woffington, known all her life as Peg, was born in Dublin in 1718. At the age of eight, her mother placed her under the tutelage of Signora Violante, an Italian acting teacher and would-be impresario, who was also an expert tightrope walker.1 Peg made her stage debut as a member of a cast of children, called the Lilliputians, in Violante’s comic version of John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, the biggest musical hit of the eighteenth century.2 She played Macheath, the first of her many male roles. A charming child actress, Peg sang ballads and danced jigs on the Dublin stage. She played her first dramatic role in 1737, as Ophelia in Hamlet, replacing an actress who had fallen ill. Three years later she moved to London’s Covent Garden Theatre, where she performed a variety of mostly comic roles for a salary of £5 a week.3

Woffington quickly became a sensation in the “breeches” part of Sir Harry Wildair, the elegant, good-humored, womanizing hero of George Farquhar’s Restoration comedy, The Constant Couple. She had first played the role in Dublin, but it was in London, at Covent Garden and later at Drury Lane, that she acquired fame in the part. Soon, an announcement that Woffington was to play Sir Harry guaranteed a full house. As a well-bred rake, she tripped lightly across the stage, humming a tune, followed by two obsequious footmen. The audience saw no trace of a woman, but only a nonchalant, well-spoken young man of faultless figure and polished manners.4 While no woman could represent the character of a man with such ease and elegance, she performed Sir Harry better than any other actor, male or female.5

Critics praised Peg in other cross-dressing roles, including those written by Shakespeare: as Portia in The Merchant of Venice; Viola in Twelfth Night; and Rosalind in As You Like It.6 She could always fill the house; her very appearance on the stage would occasion a burst of applause. Despite the masculine associations, all accounts of her depict an enchanting woman and actress. Peg was slightly taller than average, with a graceful figure, luminous eyes, a beautiful complexion, a slightly aquiline nose, and soft, full lips.7 An admirer wrote that she “was so happily made, and there was such symmetry and proportion in her frame, that she would have borne the most critical examination of the nicest sculptor.”8 The word “witchcraft” was frequently used to explain the hold Woffington had on audiences. She played aristocratic ladies as well as chambermaids, all with great success. There was a quality about her that playgoers found enchanting; a critic wrote, “She first steals your heart and then laughs at you as secure of your applause.”9 In 1740, a newspaper critic paid tribute to Peg’s androgyny in verse:

When first in petticoats you trod the stage,

Our sex with love you fired, your own with rage:

In breeches next, so well you played the cheat –

The pretty fellow and the rake complete Each sex was then with different passions moved: The men grew envious and the women loved!10

Seeing a woman play men’s roles put some theatre-goers off. One woman wrote after she saw Peg play Sir Harry:

I never saw anything done with more life and spirit; but . . . we see when things are out of nature, though they may have many beauties, in the whole they will not please, and a beard and a deep voice are as proper to make a man agreeable, as a soft voice and smooth face to a woman.11

Others complained she had an unpleasant grating voice, and that she paid too much attention to the audience’s reaction, speaking her lines “as a stranger to what was said last.”12

Woffington was well-liked off, as well as on, the stage.13 One contemporary wrote: “There was a je ne sais quoi about this lady that rendered her extremely agreeable; she was sensible, witty, and full of vivacity; her countenance was beautiful and expressive, and her form was elegant.”14 Perhaps her most endearing quality was her dislike of hypocrisy. Her unwillingness to affect a modesty she didn’t have gave her something of a reputation for loose morals, not unusual for an actress in those days.15 Peg frankly admitted that she preferred the company of men to that of women, who, she said, talked of nothing but silks and scandal. One evening when she was performing the male role of Sir Harry, she ran off the stage exultantly crying to her colleagues backstage: “Upon my honor, I believe half the audience believes me to be a man,” at which her fellow actress Kitty Clive replied archly, “Do not be uneasy, the other half know you to be a woman.”16

It is hardly surprising that David Garrick found Peg irresistible, both as an actress and as a woman. He was introduced to her before he had decided to become a professional actor, and he regularly attended her performances at Covent Garden.17 When Peg joined the Drury Lane company in September 1741 and Garrick did the same the following spring, they became acting partners, Peg taking the role of Cordelia to Garrick’s Lear in King Lear.18 A year or so before Garrick met Woffington, he himself had performed the role of Sir Harry Wildair in the country theatre at Ipswich, which he later did three more times, once on a benefit night for Woffington.19 But no male performer, not even Garrick, matched Peg’s success in the part.20

The manager of the Smock Alley Theatre in Dublin invited Garrick and Woffington to play there in the summer of 1742. On June 8, the Dublin Mercury, celebrating both the expected arrival of the actor who had become the sensation of London and the return of their homegrown star, announced that “the famous Mr. Garrick and Miss Woffington are hourly expected from England to entertain the nobility and gentry during the summer season, when especially the part of Sir Harry Wildair will be performed by Miss Woffington.” Four days later, crowds lined up on the quay to welcome them when their ship arrived in the Irish capital.21

Ireland in the eighteenth century was an oppressed colony of England. Although its population was predominantly Roman Catholic, absentee English or Anglo-Irish Protestants owned most of the land. The English Parliament legislated on Irish affairs; and, while Ireland had its own Parliament, it could make no laws without the approval of the English King and Council.22 Executive power was exercised by a Lord Lieutenant, who was usually an English nobleman appointed by the King.

Dublin, with a population of about 100,000, was the sixth largest city in Europe, after London, Paris, Constantinople, Moscow, and Rome.23 Almost all visitors to the city remarked on the extreme disparity of wealth and poverty. Cheap labor and the low price of food enabled the elite to live in luxury on the rents of their large estates. They displayed a passion for show, giving elaborate dinner parties where enormous amounts of food and wine were consumed. Even people with moderate incomes kept a carriage with four horses, a coachman, a footman, and at least one postilion riding with the coachman.24 By contrast, the poor lived in indescribable filth and squalor. A visitor reported finding “ten to sixteen persons, of all ages and sexes, in a room not 15 feet square, stretched on a wad of filthy straw, swarming with vermin, and without any covering, save the wretched rags that constituted their wearing apparel.”25

The upper classes did not just eat and drink; they also supported the arts, including the theatre.26 Dublin’s principal stage, the Smock Alley Theatre, was on a narrow, squalid street close by the River Liffey but a short walk from the grandeur of the Castle, the seat of Ireland’s government. Smock Alley produced first-rate performances of Shakespeare, as well as Restoration and contemporary drama. All that summer, Garrick and Woffington performed before full houses. They rehearsed all morning and put on a different play nearly every evening.27 Three hours before curtain time, members of the nobility sent their footmen to hold their seats for them. That summer Peg gave several performances as Sir Harry; and Garrick played Hamlet (for the first time) to her Ophelia, Lear to her Cordelia, and Richard III to her Lady Anne.28 The Dublin Journal inquired publicly how so tenderhearted a man as Garrick could be so convincing as the murderous Richard III. It was an unusually hot summer, and some sort of epidemic broke out, which Dubliners called “Garrick fever,” associating it with the great crowds that turned out to see him perform.29

By the time Garrick and Woffington returned to London in August they had become lovers. The fact that nobody was present when he seduced her (or possibly vice versa) did not deter a memoirist from describing the seduction in detail. Whether or not the account is strictly based on fact, it is probably a fair portrayal of his attraction to her, and her flirtatious charms:

Our Heroine had a curious Collection of Pictures in her Bed-chamber, which Roscius wanted to see. She wondered a little at the Joke, but laughed it away. He insisted on her shewing them to him, but she refused. The Actor rumpled her Handkerchief, but the Actress reinstated his. He jumped to catch a Kiss, but missed his Aim. Yet, as drowning Men will catch at any Twigs to save themselves, so Men likely to fall, as was our Actor’s Case, will lay hold of any Thing that is in their Way. He caught her by the Neck, and almost smothered her with Kisses. His Kisses, like the genial Sun that Thaws the congealed Ice, melted her into good Nature. Her dying Eyes, her tender sighs, her heaving Breast, her panting Waist, her lovely Charms, her clasping Arms, convinced him she was mortal; which by her wondrous Beauty, he had before almost doubted. He again enforced his Request; he took her by the Hand, and led her into her Room. They stumbled over a bed. She fell prostrate on it. He fell on her. She struggled, he trembled.30

However much in love, Woffington kept her independent spirit. One evening Garrick, standing in the theatre wings one evening, greeted her as she came off the stage after acknowledging the applause of the audience. He took her hand and said: “You are the queen of all hearts, my dear.” “Yes,” she replied, “queen of all hearts—and legal mistress of none.”31

When Garrick and Woffington returned from their summer season in Dublin, their own future and the future of the Drury Lane Theatre looked bright. Less than a year after his debut on the London stage, Garrick was already well known to playgoers as the apostle of a new, natural style of acting that drove out the bombast of the previous age; while the winsome Woffington could always fill the house, either as Sir Harry Wildair, as a Shakespearean heroine, or as a soubrette in a contemporary comedy or farce. They headed a brilliant company that also included Macklin and Kitty Clive, a favorite with audiences for her singing voice, vivacity, and sheer good humor. During the 1742–43 season at Drury Lane, one of the most brilliant in the history of the London stage, Garrick and Woffington played opposite each other in several Shakespearean and other works; in March there was a benefit performance32 for Peg, in which Garrick took over Peg’s part of Sir Harry in The Constant Couple, while she played the female lead. The primarily male audience, which had anticipated having a view of Woffington’s shapely legs, was not happy with the casting.33

In January 1743, Garrick and Woffington took up lodgings in the same house as Macklin’s on Bow Street, close by the theatre. There were rumors that they had a ménage à trois, but this is highly unlikely, given Garrick’s passion for Woffington and his jealous nature, and Macklin’s domesticity with his wife and eight-year-old daughter.34 Both Garrick and Macklin wanted to propagate the new realistic acting style, and the three of them hoped to use the house as a school for young actors. But little came of this arrangement, and several years were to pass before the two men were to become teachers and mentors, Garrick as manager at Drury Lane and Macklin for a short time as proprietor of his own school of acting. Guests at the Bow Street house included the actors Samuel Foote and Colley Cibber, the literary giant Samuel Johnson, and the poet, playwright, and major novelist Henry Fielding. Garrick, Woffington, and Macklin agreed that they would alternately defray the monthly expenses. Garrick had a reputation for parsimony, and it was a standing joke that dinners for their visitors were sparser during the months when it came time for him to pay.35

The lovers’ relationship was turbulent, but for a time it survived her flings with others. He entreated her not to see a certain admirer. One evening, he asked her how long since she had seen the man. “Not for an age,” she said. He retorted that he knew she had seen him that morning. Going up to him and pouting like a child, she purred, “I count time by your absence; I have not seen you since this morning, and is it not an age since then?”36 The smitten Garrick wrote a poem to his beloved. It is not recorded how Peg reacted to the following stanza:

By age your beauty shall decay,

Your mind improve with years;

As when the blossoms fade away,

The ripening fruit appears.37

A nobleman who was having an affair with Woffington liked to visit her from time to time. Garrick, whom she had apparently persuaded to overcome his jealousy and countenance the arrangement, was in bed with her one night when the lord came by unannounced and knocked loudly on the door. Garrick jumped up hastily gathered up his clothes, hurried upstairs to Macklin’s apartment, and asked him if he could have the use of a bed for the night. Then he discovered to his dismay that he had left his wig (in those days, an essential component of a gentleman’s clothing) in Peg’s bedroom. Despite Macklin’s calming reassurances, Garrick spent an anxious night. Meanwhile the nobleman discovered the wig and berated Peg for infidelity. Thinking quickly, she replied that it was her wig; she was scheduled to play a breeches part and was practicing it before going to bed. His lordship begged for forgiveness on his knees “and the night was passed in harmony and good humour.”38

Although there were unfounded rumors that Garrick and Woffington had secretly married, the truth was that she would have liked to marry him but he was reluctant. Peg later told a friend that Garrick had gone so far as to try a wedding ring on her finger.39 But their affair lasted not much longer than a year. When she pressed him about marriage, he refused. “Then, sir,” she said, “from this hour I separate myself from you, except in the course of professional business, or in the presence of a third person.”40 She kept her word, returning to him all the presents he had given her; and he did the same, except for a pair of diamond shoe buckles. When she asked for them back, he said he hoped she would permit him to keep the buckles as memorials of the many happy hours they had spent together. She relented, and he kept them for the rest of his life.41

Garrick had some regrets about the end of the relationship and for a while wanted to be reconciled to her.42 But in a letter he wrote to a friend two years after the breakup, he insisted, with a touch of bravado, that he was no longer under her spell:

Woffington, I am told, shews my letters about; pray have you heard any thing of that kind? What she does now, so little affects me, that, excepting her shewing my letters of nonsense and love to make me ridiculous, she can do nothing to give me a moment’s uneasiness – the scene is changed – I’m alter’d quite.43

On the rebound, he made a pass at Susannah Cibber, an elegant Drury Lane actress and the finest singer in London—Handel altered one of the songs in The Messiah to bring it within the range of her voice.44 Cibber had left an abusive husband for a permanent, but unwed, relationship with a wealthy gentleman.45 She turned Garrick down gently but firmly with the words: “I desire you always to be my lover upon the stage, and my friend off of it.”46 Rejected, he turned to his main passion, acting.

Notes

1 Molloy, The Life and Adventures of Peg Woffington, i, 8–10; Maxwell, Dublin Under the Georges, 222.

2 Shaughnessy, eds. Lives of Shakespearean Actors: Woffington, iii, 208–10.

3 Brooks, Actresses, Gender, and the Eighteenth-Century Stage: Playing Women (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 18.

4 Molloy, The Life and Adventures of Peg Woffington, i, 82–83.

5 David Thomas, ed., Restoration and Georgian England 1660–1788 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 383 (part of a series, Theatre in Europe: A Documentary History); Shaughnessy, eds., Lives of Shakespearean Actors: Woffington, iii. 225.

6 Brooks, Actresses, Gender, and the Eighteenth-Century Stage, 64.

7 Molloy, The Life and Adventures of Peg Woffington, i, 80–81.

8 Anon., The Life of James Quin, 40.

9 Cecil Price, Theatre in the Age of Garrick (Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield, 1973), 39–40.

10 Shaughnessy, eds., Lives of Shakespearean Actors: Woffington, iii, x-xi.

11 Elizabeth Robinson Montagu, Correspondence of Elizabeth Montagu from 1720 to 1761 (New York: E.P. Dutton & Company, 1906), 92–93.

12 Wilkinson, Memoirs, 22; Shaughnessy, Lives of Shakespearean Actors: Woffington, iii, 114.

13 Davies, “Memoirs of the life of David Garrick,” in Lives of Shakespearean Actors: Woffington, iii, 215

14 Shaughnessy,eds., Lives of Shakespearean Actors: Woffington, 226.

15 Ibid., Lives of Shakespearean Actors: Woffington, 114.

16 Wilkinson, Memoirs, 30. Another contemporary writer attributed the response to the actor James Quin. Shaughnessy, Lives of Shakespearean Actors: Woffington, iii, 38.

17 Molloy, The Life and Adventures of Peg Woffington, i, 114.

18 Shaughnessy, eds. Lives of Shakespearean Actors: Woffington, iii, xiii.

19 Private Correspondence of Garrick (V&A), vi, xii; Stone and Kahrl, David Garrick, 658.

20 Wilkinson, Memoirs, 39–30.

21 Molloy, The Life and Adventures of Peg Woffington, i, 150–53; Dunbar, Peg Woffington and Her World, 86.

22 Constantia Maxwell, Dublin Under the Georges 1714–1830 (London: Faber and Faber Limited, 1936), 30.

23 Esther K. Sheldon, Thomas Sheridan of Smock-Alley (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1967), 32.

24 Maxwell, Dublin Under the Georges, 100–03.

25 Ibid., 140.

26 Ibid., 100.

27 Dunbar, Peg Woffington and Her World, 87.

28 Molloy, The Life and Adventures of Peg Woffington, i, 154–57.

29 Sheldon, Thomas Sheridan of Smock-Alley, 29; Maxwell, Dublin Under the Georges, 231–32.

30 Shaughnessy, eds. Lives of Shakespearean Actors: Woffington, iii, 51.

31 Dunbar, Peg Woffington and Her World, 88.

32 It was a practice to give each actor a benefit night every year; the actor would get the receipts of the house, less its expenses, and the other actors would give up their salaries for that night. See Chapter 8.

33 McIntyre, Garrick, 66.

34 Shaughnessy, eds., Lives of Shakespearean Actors: Woffington, iii, 221–22.

35 Molloy, The Life and Adventures of Peg Woffington, i, 174–75.

36 Ibid., i, 119–20.

37 George Pierce Baker, ed., Some Unpublished Correspondence of David Garrick (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin and Company, 1907), 132.

38 Cooke, Memoirs of Charles Macklin, Comedian, 116–18.

39 Private Correspondence of Garrick (V&A), xxii; Molloy, The Life and Adventures of Peg Woffington, i, 185–86.

40 Molloy, The Life and Adventures of Peg Woffington, i, 186–90.

41 Cooke, Memoirs of Charles Macklin, Comedian, 120–22.

42 George Anne Bellamy, Apology for the Life of George Anne Bellamy (London: J. Bell, 4th ed. 1781), i, 47.

43 David Garrick to Somerset Draper, Oct. 23, 1745, Little and Kahrl, eds., The Letters of David Garrick, i, 65.

44 Dunbar, Peg Woffington and Her World, 85.

45 Little and Kahrl, eds., The Letters of David Garrick, i, 322.

46 Mrs. Susannah Cibber to David Garrick, Nov. 9, 1745, Boaden, Private Correspondence of David Garrick, i, 38–39.