Nights past when they had managed to build shelters were nothing compared to this one, for the women were so tired they could barely move. In blind determination they stumbled about gathering spruce boughs for their beds and large chunks of wood for the campfire. Finally, they huddled together and stared as if hypnotized into the large orange blaze they ignited from the live coals carried from the first campsite. Soon they slipped mindlessly off to sleep. They did not hear the lonesome howl of a distant wolf, and before they knew it the cold air of morning brought them back to their senses.

They had fallen asleep leaning against one another and somehow managed to stay in that position all night. Because they were sitting up on their legs, the women knew getting up would not be easy. They sat still for a long time. Then Sa’ made an effort to rise, but her legs had lost their feeling. She grunted and tried again. Meanwhile, Ch’idzigyaak closed her eyes tightly and pretended to be asleep. She did not want to face the day.

Sa’ gathered a little courage to force herself to move, but the aches in her bones proved to be too much for her this time. Again they had pushed their bodies beyond their limits. Without meaning to, Sa’ let out a painful moan, and she felt a great urge to cry. She hung her head, defeated by all they had been through these past few days, and the cold made her feel even more despair. As much as she wanted to, her body would not move. She was too stiff.

Ch’idzigyaak listened lethargically to her friend’s sniffles. She was amazed that she could sit and listen to Sa’ cry and feel no emotion. Perhaps it was not meant for them to go on. Perhaps the young ones were right—she and Sa’ were fighting the inevitable. It would be easy for them to snuggle deeper into the warmth of their fur clothing and fall asleep. They would not have to prove anything to anyone anymore. Perhaps the sleep that Sa’ feared would not be so bad after all. At least, Ch’idzigyaak thought to herself, it would not be as bad as this.

Yet, for as little will as her older friend had, Sa’ possessed enough determination for both of them. Shrugging off the cold, the pain in her sides, her empty stomach, and the numbness in her legs, she struggled to get up and this time succeeded. As had become her morning habit, she limped around the campsite until feeling slowly began to course through her bloodstream. When the circulation returned, there was more pain. But Sa’ concentrated her attention on gathering more wood to build the fire. Then she boiled a rabbit head to make a tasty broth.

Ch’idzigyaak watched all this from between narrowed lids. She did not want her friend to know that she was awake, for then, Ch’idzigyaak felt, she would be obligated to move, and she did not want to move. Not now and not ever. She would stay exactly as she was, and perhaps death would steal her quickly away from the suffering. But her body was not ready to give in just yet. Instead of slipping blissfully into oblivion, Ch’idzigyaak suddenly felt the urgent need to relieve her bladder. She tried to ignore this, but soon her bladder could wait no more, and with a loud grunt she felt her bladder letting go. In quick panic she jumped up and headed for the willows, startling her friend. When Ch’idzigyaak came out of the willows looking slightly guilty, Sa’ tilted her head in wonder. “Is something wrong?” she asked. Ch’idzigyaak, feeling embarrassed, admitted, “I surprised myself by how fast I moved. I did not think I would be able to move at all!”

Sa’ was thinking of the day ahead. “After we have eaten, we should try to move on, even if we go only a little way today,” she said. “Each step brings us closer to where we are going. Although I do not feel good today, my mind has power over my body, and it wants us to move on instead of staying here to rest—which is what I want to do.” Ch’idzigyaak listened as she ate her portion of the rabbit head and broth. She, too, felt like staying there for a while. In fact, she desperately wanted to stay. But after putting aside her foolish thoughts, she felt ashamed and reluctantly agreed they should move on.

Sa’ felt a slight disappointment when Ch’idzigyaak agreed to resume their journey, wondering if deep within her she had hoped Ch’idzigyaak would refuse to move. But it was too late for second thoughts. So both women tied the ropes around their thin waists and pulled onward. As they walked, they kept their eyes open for signs of animals, for their food was nearly gone, and meat was their prime source of energy. Without it, their struggle would be over soon. Sometimes, the women stopped to discuss the route they had chosen and to ask themselves if it was the correct way. But the river led in only one direction from the slough, so the women walked along the riverbank as they kept a lookout for the narrow creek that would lead them to a place remembered for its plentiful fish long ago.

The days dragged on as the women slowly pulled their sleds across the deep snow. On the sixth day, Sa’, who had grown accustomed to staring dully only at the path ahead, happened to glance up. Across the river she saw the opening to the creek. “We are there,” she said in a soft, breathless voice. Ch’idzigyaak looked at her friend, then at the creek. “Except we are on the wrong side,” she said. Sa’ had to smile at her friend, who always seemed to find the negative side of a situation. Too tired to offer a lighter point of view, Sa’ sighed to herself as she motioned to her friend to follow.

This time the two women did not worry about hidden cracks beneath the ice. They were too tired. Mindless of the danger, they crossed the frozen river and kept right on going up the tributary. The women walked until late that night. The moon slowly emerged over the trees until it hovered above them, lighting their way along the narrow creek. Although they had walked more hours than they had on earlier days, the women continued on. They felt sure the old campsite was near and they wanted to reach their destination that night.

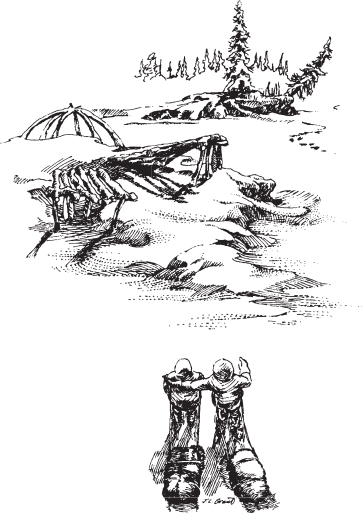

Just about the time Ch’idzigyaak was ready to beg her friend to stop, she saw the campsite. “Look over there!” she cried. “There are the fishracks we hung so long ago!” Sa’ stopped and suddenly felt weak. It was with great effort that she stood on her shaking legs, for a feeling of somehow coming home suddenly overwhelmed her.

Ch’idzigyaak moved closer to her friend and gently placed an arm around her. They looked at each other and felt a surge of powerful emotion that left them speechless. They had traveled all this way by themselves. Good memories came back to them about the place where they had shared much happiness with friends and family. Now, because of an ugly twist of fate, they were here alone, betrayed by those same people. Because they were thrown together in hardship, the two women developed a sense of knowing what the other was thinking, and Sa’ was usually the more sensitive one.

“It is better not to think of why we are here,” she said. “We must set up our camp here tonight. Tomorrow we will talk.” Clearing the bitter emotion from her throat, Ch’idzigyaak heartily agreed. So, with slow, dragging movements, the two women climbed up the low bank of the creek and walked to the campsite, where they found an old tent frame that they used for shelter that night.

Though their clothing shielded them from the awful cold, the caribou skins did a better job. Coals from the fire pulsated amidst the ash all through the night and kept the shelter warm. Finally, the morning cold seeped through, and the women began to stir. Sa’ was the first to move. This time her body did not protest so much as she moved about the shelter, placing the wood they had gathered the night before on the tiny embers still burning in the fireplace. After a few moments of softly blowing the dried sticks, a flame began a gentle dance as it spread onto the bundle of dry willows. Soon the shelter was warm and glowing.

That day, the women worked steadily, unmindful of their aching joints. They knew they would have to hurry to make final preparations for the worst of the winter, for even colder weather lay ahead. So they spent the day piling snow high around the shelter to insulate it and gathering all the loose wood they could find. Then without resting, they set a long line of rabbit snares, for the area was rich in willow, and there were many signs of rabbit life. Nighttime had arrived when the women made their way back to the camp. Sa’ boiled the remains of the rabbit’s innards and the women feasted on the last of their food. After that, they leaned against their bedding and stared into the campfire.

The two women had not known each other well before being abandoned. They had been two neighbors who thrived on each other’s bad habit of complaining and on sharing conversations about things that did not matter. Now, their old age and their cruel fate were all they had in common. So it was that night, at the end of their painful journey together, they did not know how to converse in companionship, and instead, each woman dwelled on her own thoughts.

Ch’idzigyaak’s mind went immediately to her daughter and grandson. She wondered if they were all right. A surge of hurt streaked through her as she thought about her daughter again. It was still hard for Ch’idzigyaak to believe that her own flesh and blood would refuse to come to her aid. As the self-pity overwhelmed her, Ch’idzigyaak fought the tears that threatened to spill from her eyes, and her lips formed a thin, rigid line. She would not cry! This was the time to be strong and to forget! But with that thought a huge single tear dripped down. She looked at Sa’ and saw that she also was lost deep in thought. Ch’idzigyaak was perplexed by her friend. Except for a few moments of weakness, the woman next to her seemed strong and sure of herself, almost as if she were challenged by all of this. Curiosity replaced her pain and Sa’ was startled when Ch’idzigyaak spoke.

“Once when I was a little girl, they left my grandmother behind. She could no longer walk and could hardly see. We were so hungry that people were staggering around, and my mother whispered that she was afraid that people would think of eating people. I had not heard of anything like this before, but my family told stories of some who had grown desperate enough to do such things. My heart filled with fear as I clung to my mother’s hand. If someone looked into my eyes, I would turn my head quickly, fearing he might take notice of me and consider eating me. That is how much fear I had. I was hungry, too, but somehow it didn’t matter. Perhaps it was because I was so young and had my family all around me. When they talked about leaving my grandmother behind, I was horrified. I remember my father and brothers arguing with the rest of the men, but when my father came back to the shelter, I looked at his face and knew what would happen. Then I looked at my grandmother. She was blind and too deaf to hear what was going on.” Ch’idzigyaak took a deep breath before continuing with her story.

“When they bundled her up and put her blankets all around her, I think Grandmother sensed what was happening because as we began to leave the camp I could hear her crying.” The older woman shuddered at the memory.

“Later, when I grew up, I learned that my brother and father went back to end my grandmother’s life, for they did not want her to suffer. And they burned her body in case anyone thought of filling their bellies with her flesh. Somehow, we survived that winter, though my only real memory of that time was that it was not a happy one. I remember other times of empty stomachs, but none as bad as that one winter.”

Sa’ smiled sadly, understanding her friend’s painful memories. She, too, remembered. “When I was young, I was like a boy,” she began. “I was always with my brothers. I learned many things from them. Sometimes, my mother would try to make me sit still and sew, or learn that which I would have to know when I became a woman. But my father and brothers always rescued me. They liked me the way I was.” She smiled at her memories.

“Our family was different from most. My father and mother let us do almost anything. We did chores like everyone else, but after they were done, we could explore. I never played with other children, only with my brothers. I am afraid I did not know what growing up was about because I was having so much fun. When my mother asked me if I had become a woman yet, I did not understand. I thought she meant in age, not in that way. And summer after summer, she would ask me the same question, and each time she looked more worried. I did not pay much attention to her. But as I grew as tall as my mother and just a little shorter than my brothers, people looked at me in a strange way. Girls younger than me already were with child and man. Yet I was still free like a child.” Sa’ laughed heartily as she now knew why she received all those strange looks from people then.

“I began to hear them laugh at me behind my back and I became confused. In a way, I did not care what people thought about me, so I continued to hunt, fish, explore, and do what I pleased. My mother tried to make me stay home and work, but I rebelled. My brothers had taken women, and I told my mother she had plenty of help, and with that I would escape. When my mother turned to my father to discipline me, I would show up with a huge bundle of ducks, fish, or some other food, and my father would say, ‘Leave her alone.’ Then I grew older, beyond that age when women should have man and child, and everyone was talking about me. I could not understand why, for although I was not with a man and having children, I was still doing my share of the work by providing food. There were times when I brought more food than the men. This did not seem to please them. About this time in my life, we experienced our worst winter. It was cold like this.” Sa’ motioned with her hand.

“Even babies died, and grown men began to panic, for as hard as they tried they could not find enough animals to eat. There was an old woman in our group whom I rarely noticed. The chief decided we had to move on in our search for food. There was a rumor that far away we would find caribou. This excited everyone.

“The old woman had to be carried. The chief did not want this burden, so he told everyone that we would leave her behind. No one argued, except me. My mother tried to stifle me, but I was young and unthinking. She told me that this was to be done for the sake of the whole group. She seemed like a cold, unfeeling stranger as she tried to talk me out of my protest, but I angrily brushed her off. I was shocked and furious. I felt that The People were being lazy and were not thinking clearly. It was my job to talk some sense into them. And being who I was, I spoke up for the woman whom I hardly knew existed until then. I asked the men if they thought they were no better than the wolves who would shun their old and weak.

“The chief was a cruel man. I had avoided him until the day I stood before him and shouted angry words at his face. I could see that he was twice as angry as I was, but I could not stop myself. Even though I knew that the chief disliked me, I argued on, not listening to him as he tried to answer my accusations. His action was wrong, and I meant to make it right. As I continued to talk, I was unaware of the shock that awakened the group from its malnourished lethargy. A fearful look fell upon the chief’s face and he put his large hand over my mouth. ‘All right, strange young girl,’ he said in a loud voice that I knew was meant to humiliate me. I could feel my chin go up farther so that he could see that I remained proud and unafraid. ‘You will stay with the old one,’ he said. I could hear my mother gasp, and my own heart sank. Yet I would not yield as I stared unblinkingly into his eyes.

”My family was deeply hurt, but pride and shame kept them from protesting. They did not want a daughter who would take such a stand against the strong leaders of the group. I did not think the leaders were strong. The chief acted as if I did not exist after that, and I was ignored by everyone else except my family, who begged me to apologize to the leader. But I would not give in. My pride grew with each moment the others pretended I was not there, and I continued to plead for the old woman’s life.” Sa’ broke into laughter at her impetuous youth.

“What happened after that?” Ch’idzigyaak wanted to know.

Sa’ paused as she deeply inhaled the pain from those long-ago memories. Continuing in a subdued voice, she said, “After they left, I was not so brave. There were no animals to be found for miles around. But I was determined to show what could be done by my good intentions. So the old woman—I never did know her name, for I was too busy trying to keep us alive—and I ate mice, owls, and anything else that moved. I killed it, and we ate it. The woman died that winter. Then I was alone. Not even my pride and usual carefree ways could help me. I talked to myself all the time. Who else was there? They would think I was crazy if The People returned to find me talking to the air. At least you and I have each other,” Sa’ told her friend, who nodded in wholehearted agreement.

“Then I realized the importance of being with a large group. The body needs food, but the mind needs people. When the sun finally came hot and long on the land, I explored the country. One day as I was walking along, talking to myself as usual, someone said, ‘Who are you talking to?’ For a moment I thought I was hearing things. I stopped in my tracks and turned slowly to find a big, strong-looking man with his arms crossed, smiling at me in a bold manner. Many feelings ran through me at that moment. I was surprised, embarrassed, and angry all at once. ‘You scared me!’ I said, trying to cover up my real feelings. Because my cheeks were burning, I knew I did not fool him, for his grin grew deeper. He asked me what I was doing out there alone, and I told him my story. I felt at that moment that I could trust him. He told me that the same thing happened to him. Only he was banished because he was foolish enough to fight over a woman who was meant for another man. We were together a long time before we became a man and woman together. I never saw my family again, and it was years later that we joined the band.

“Then he tried to fight with a bear and died. Foolish man,” she added with grudging admiration, as a deep sadness weighed down her face.

It was the first time Ch’idzigyaak saw her friend so sad, and she broke the silence by saying, “You were luckier than I, for when it became apparent that I was not interested in taking a man, I was forced to live with a man much older than me. I hardly knew him. It was years before we had our child. He was older than I am now when he died.”

Sa’ laughed. “The People would have chosen a man for me too, had I been with them much longer.” After a momentary silence, she continued. “Now here we are, truly old. I hear our bones creaking, and we are left behind to fend for ourselves.” The women fell into silence as they struggled with their emotions. They lay on their warm beds as the cold earth trembled outside. They thought about the experiences they had shared. As they fell into an exhausted sleep, each woman felt more at home because of her new knowledge of the other and because each had survived hard times before.

Days shortened as the sun sank deeper under the horizon. It grew so cold there were times when the women jumped as the trees around them cracked loudly from the cold pressure. Even the willows snapped. But as the women settled down they also became depressed. They feared the savage wolves that howled in the distance. Other imagined fears tormented them as well, for there was plenty of time to think as the dark days drifted slowly by. In what daylight they had, the two women forced themselves to move. They spent all their waking hours collecting firewood from underneath the deep snow. Though food was scarce, warmth was their main concern, and at night they would sit and talk, trying to keep each other from the loneliness and fears that threatened to overcome them. The People rarely spent precious time in idle conversation. When they did speak, it was to communicate rather than to socialize. But these women made an exception during the long evenings. They talked. And a sense of mutual respect developed as each learned of the other’s past hardships.

Many days went by before the women caught more rabbits. It had been some time since they had eaten a full meal. They managed to preserve their energy by boiling spruce boughs to serve as a minty tea, but it made the stomach sour. Knowing it was dangerous to eat anything solid after such a diet, the two women first boiled the rabbit meat to make a nourishing broth, which they drank slowly. After a day of drinking the broth, the women cautiously ate one ham off a rabbit. As the days passed, they allowed themselves more portions, and soon their energy was restored.

With wood piled high around the shelter like a barricade, the women found that they had more time to forage for food. The hunting skills they learned in their youth reemerged, and each day the women would walk farther from the shelter to set their rabbit snares and to keep an eye out for any other animals small enough to kill. One of the rules they had been taught was that if you set snares for animals you must check them regularly. Neglecting your snareline brought bad luck. So, despite the cold and their own physical discomforts, the two women checked their snares each day and usually found a rabbit to reward them.

At nightfall, when their daily chores were completed, the women wove the rabbit fur into blankets and clothing, such as mittens and face coverings. Sometimes, to break the monotony, one would present a woven rabbit-fur hat or mittens to the other. This always brought wide smiles.

As the days slowly passed, the weather lost its cold edge, and the women savored moments of glee—they had survived the winter! They regained what energy they had lost and now they kept busy collecting more firewood, checking the rabbit snares and scouting the vast area for other animals. Though the women had lost the habit of complaining, they grew tired of the daily fare of rabbit meat and found themselves dreaming of other game to eat, such as willow grouse, tree squirrels, and beaver meat.

One morning, as Ch’idzigyaak awoke, she felt something was not quite right. Her heart pumped rapidly as she slowly got up, fearing the worst, and peeked out of the shelter. At first, all seemed still. Then suddenly she spotted a flock of willow grouse pecking at some tree debris that had fallen not far away. With trembling hands, she quietly got a long, thin strand of babiche out of her sewing bag and slowly crept out of the tent. Selecting a long stick from the nearby woodpile, she fashioned a noose at the end and began to crawl toward the flock.

Nervously, the birds started to cluck as they became aware of the woman’s presence. Knowing that the birds were about to take fight, Ch’idzigyaak stopped for a few minutes to give them time to calm down. They were not too far from her now, and she hoped that Sa’ would not awake and make a noise that would scare away the birds. With knees aching and hands slightly trembling, Ch’idzigyaak slowly pushed the stick forward. Some grouse excitedly flew away to another patch of willows nearby, but she steadfastly ignored them as she continued to lift the stick slowly as the remaining birds walked about faster. Ch’idzigyaak concentrated on the grouse closest to her. It made small movements toward the noose, its head nodding back to front. As the birds started noisily to run and fly off, Ch’idzigyaak shoved the noose forward until the bird’s head slipped right into it. Then she jerked the stick upward as the bird squawked and twisted until it hung motionless. Standing up with the dead grouse in her hand, Ch’idzigyaak turned toward the tent to find her friend’s face wreathed in smiles. Ch’idzigyaak smiled back.

Looking into the air, Ch’idzigyaak took note of a warmth in the air. “The weather gets better,” Sa’ said softly and the older woman’s eyes widened in surprise. “I should have noticed. Had it been cold, I would have frozen in my position of a sneaky fox.” The women found great laughter in this as they went back into the shelter to prepare the meat of a different season to come. After that morning, the weather fluctuated between bitter cold and then warm and snowy days. That the women did not catch another bird failed to dampen their spirits, for the days gradually grew longer, warmer, and brighter.