8

Pets’ Day

Like most people who keep diaries, Judy wrote in hers each evening. But as soon as she woke on the morning that had been chosen for Pets’ Day, she opened it.

SEPTEMBER 11th: Today it if Pets’ Day at school! Jenius will tryumph! * Watch this space! *

At breakfast time she could not contain herself. Till now she had said nothing to her parents – as she had sworn on July 23rd – of the progress of the Jenius, but she just knew she would not be able to resist describing the success that was to come before another hour had passed.

‘What d’you think is happening today?’ she said.

‘You’re going to be late for school,’ said her mother, ‘if you don’t hurry up. And clean your shoes before you go. And take your anorak – it looks like rain.’

‘I’m taking Jenius to school,’ said Judy.

‘Very nice, dear,’ said her mother. ‘Now, do you want an apple or a banana in your lunch box?’

‘Apple,’ said Judy. ‘Dad, did you hear what I said?’

‘I did,’ said her father from behind his morning paper. ‘Will he have to start in the Infants or is he clever enough to go straight into your class?’

‘Oh Dad!’ cried Judy. ‘Honestly, I really have trained him,’ and she rattled off a list of the things that Jenius could do.

‘Judy,’ said her father. ‘You don’t really expect us to believe all this, do you?’

‘Yes,’ said Judy. ‘It’s true.’

Her father folded his newspaper.

‘Now look here,’ he said. ‘Playing pretend games with your precious pet is one thing. But you mustn’t confuse fantasy with truth.’

There was hardly room to move in Judy’s classroom that morning.

Everywhere there were hutches and cages and baskets and boxes containing pets. Only the Jenius was free, sitting perfectly still in front of Judy.

Judy’s teacher saw what seemed to her a rather odd-looking whitish guinea pig, with a crest of reddish hair sticking up along its back, and said: ‘Is this the genius we’ve heard such a lot about?’

‘Yes,’ said Judy proudly. ‘Shall I show you what he can do?’

‘All right,’ said her teacher. ‘Put him on that big table in the middle of the room where everyone can see him.’

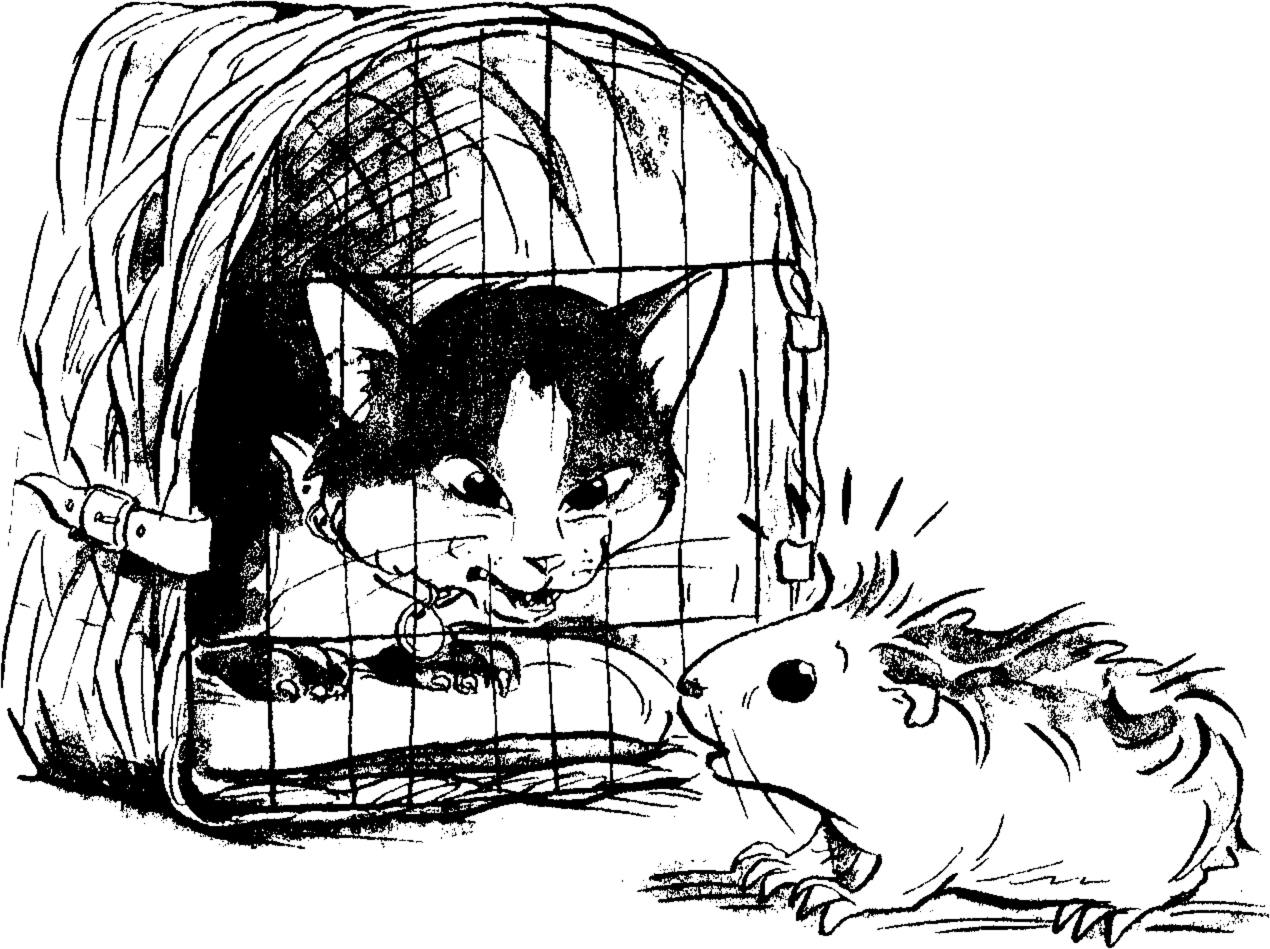

Ranged around the edges of the big table were several pet-containers: a couple of hamster-cages, a glass jar that held stick insects and a square basket that had one open side barred with metal rods.

Fate decreed that Judy should put the Jenius down quite near to this basket and facing it, and though no one else could see what was in it, he could. He looked through the bars and saw a face, a merciless face, with glowing yellow eyes and a wide mouth filled with sharp white teeth.

In fact the occupant of the basket was only a half-grown kitten, but the sight of it turned Jenius’s legs to jelly and scrambled his brains. He was so frightened that he promptly Died For His Country, and there he lay, quite still and barely breathing. He could hear Judy’s voice saying, ‘Come!’ and then, more loudly, ‘Jenius! Come!!’ Then he heard a rising tide of noise which was the whole class first sniggering, then giggling, and finally laughing their heads off at clever Judy and her clever guinea pig, about which she had boasted so loud and long. But he could not move a muscle.

‘The great animal trainer!’ someone said, and they laughed even more.

‘Perhaps that will teach you a lesson, Judy,’ said the teacher at last. ‘He doesn’t seem to be quite the genius you told us he was. You mustn’t confuse fantasy with truth.’