Earth’s natural satellite might look barren, but it’s bubbling over with misconceptions.

The footprints of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin will still decorate the Moon hundreds of years from now. The lunar surface enjoys no weather; no wind, no rain, no appreciable seasons. Only an unlucky meteorite strike or a determined vandal could disturb the Apollo landing sites. It is a quiet, peaceful world; ‘Magnificent desolation’, as Aldrin described it.

There may not be much going on above ground, but the Moon is alive on the inside. Before the crewed landings of the 1960s and 1970s, most scientists assumed that our nearest neighbour was geologically inactive. Yet when the Apollo astronauts deployed seismometers, they discovered rumbles beneath their feet. These ‘moonquakes’ are usually weak, but some could set a moon base wobbling.

Moonquakes have several causes. Small vibrations occur whenever a meteorite strikes the surface. Thermal moonquakes are caused by the lunar crust heating and expanding under sunlight. Deeper moonquakes are triggered by the Earth's gravity. The near side of the Moon feels Earth’s tug a little more than the far side. These tidal forces can set the rock a-quiver.

Shallow moonquakes – whose origins remain uncertain – are the biggest headache for would-be colonists. The seismometers left by the Apollo astronauts recorded tremors equivalent to 5.5 on the Richter scale. That’s enough to cause damage to unprotected buildings. Moonquakes also tend to last longer than earthquakes. The Moon’s dry, rigid crust just keeps on ringing like a tuning fork. A lunar base would need to take this geology into account. While a cracked building on Earth is something of a nuisance, on the Moon it could be fatal.

The Man in the Moon gazed down upon the Earth long before there was a man on the Earth to stare back. He never turns his cheek. Whenever we look at a full moon, his features are just the same. The Moon always presents the same face, so it is natural to assume that it must be fixed on its axis, unmoving.

Having read a fair chunk of this book by now, you’ve probably guessed that this is not the case. The Moon turns on its axis just like everything else in the Solar System. With a little bit of pondering, we can understand why. If you’re the type of reader who likes to skim, this is the point to slow down and indulge in a thought experiment.

First, let’s see what would happen if the Moon were not spinning on its axis. Imagine looking top-down, with the little circle of the Moon gradually moving around the larger circle of the Earth, but not turning on its own axis. Try it with two coins if that helps. What happens to the gaze of the Queen (or whomever is on your coin) as she loops round the larger Queen of the other coin? It changes. On one side of the ‘orbit’, she is looking in towards the larger coin. On the opposite side, she looks away. So without any spin, the part of the Moon facing the Earth would gradually change.

Clearly, then, the Moon must be rotating while it orbits. Further, it must turn at just the right speed to maintain the same face to the planet. Try it again with the coins. You have to turn your ‘Moon’ coin through 180 degrees for every half orbit to ensure the Queen always gazes inward at her larger self. To make it work, Her Orbiting Majesty must complete one full rotation in the time it takes to make one complete orbit.

That is exactly what happens with the Moon. A lunar day (the time it takes the Moon to rotate once upon its axis) is equal to a lunar orbit (the time it takes the Moon to complete one loop round the Earth). That time is a shade over 29.5 days and corresponds (from Earth) to the period between two new moons. Our calendar system of months is an imperfect reflection of this.

Isn’t that a remarkable coincidence? The Moon just happens to spin at precisely the right speed so that its day and orbital period match. Surely this must be evidence for God or aliens or something? Not at all. The effect is known as ‘tidal locking’. It occurs because the gravitational force of the Earth has gradually exerted a torque onto the smaller Moon, slowing down its spin and bringing it into synchrony. That sentence breezes over a whole load of complexities, but needless to say, it is a perfectly natural phenomenon. Similar set-ups can be found throughout the Solar System. The four largest moons of Jupiter, for example, always show the same face to their planetary governor. Tidal locking has even been observed in other star systems.

In the above discussion, we’ve completely ignored the rotation of the Earth. Our planet also turns on its axis. We didn’t need to take this spin into account when we were messing about with the coins – it would have added a complication that wasn’t relevant to the question. But it’s fun to flip our perspective and imagine looking at the Earth from the Moon. How would the home planet appear to move from that perspective?

The view would be rather odd. If you were to stand on the ‘far’ side of the Moon, you would never see the Earth – just as we cannot see the far side from the homeworld*. Conversely, an astronaut on the ‘near’ side of the Moon would always be able to see the Earth. More than that, our homeworld would forever stick to the same part of the sky. Those ‘Earthrise’ videos from the Apollo missions were only possible because the spacecraft was zipping around the Moon at the time. No astronaut on the lunar surface would ever see the Earth rise or fall to any appreciable degree.

It would hang there like a spinning bauble, waxing and waning as the angle of sunlight changed. It would rotate on its axis, showing different faces. It would wobble about in the sky a little due to libration (see footnote below). But it would not arc through the skies like the Moon does from Earth.

Now let’s return to the far side of the moon, to tick off one other big myth. This largely unseen portion of the surface is often called the ‘dark side’ of the Moon. Thanks to a wildly (and deservedly) popular album by Pink Floyd, we’re stuck with that nickname forever. But it’s a complete misnomer. The far side of the Moon gets just as much sunlight as the portion that we see. It is only ‘dark’ in the archaic use of the word, to mean obscured or unknown. And even that sense is now outdated, since numerous space probes have sent back detailed images of the far side.

The very first probe to image the hidden parts of the Moon was the Soviet Luna 3 on 7 October 1959. It’s a moment in history that has somehow slipped into obscurity. If you asked 100 random people to tell you the name of the first spacecraft to visit the far side of the Moon, how many would know the answer? Almost one, perhaps. But it is a stupendous achievement that should make us proud. Think about it. For millions of years, humans (and creatures that were not yet human) looked up to the white disc of the Moon with awe. It has been worshipped. It has been feared. But it always looked the same. Then, suddenly, within living memory, we saw the whole of the Moon. First robotic cameras, and then human eyeballs gazed down upon the far-side and, almost overnight, our knowledge of lunar geography doubled. Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and William Anders on Apollo 8 were the first creatures that ever lived* to directly glimpse the second hemisphere of the Moon. I think that’s awesome, in both the archaic and modern sense of the word.

* FOOTNOTE Actually, that’s a bit simplistic. You can see only 50 per cent of the Moon’s surface at any one time, but the 50 per cent on show does shift slightly throughout a month. The Moon has an elliptical orbit, which makes it appear to rock or oscillate when viewed from Earth. This effect, known as libration, gave astronomers a tantalizing glimpse round the edges of the Moon long before probes got there. In fact 59 per cent of the Moon’s surface can be seen in this way over the course of a lunar orbit.

* FOOTNOTE Assuming the tortoise of Zond 5 (see here) did not have a window seat, and that no alien has ever visited.

Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin touched down on the lunar surface on 20 July 1969. They were not alone. Another spacecraft was waiting in the Sea of Tranquillity. Just over the horizon, about a day’s walk away, lurked an emissary from a different world ...

The US sent seven robotic missions to the Moon’s surface ahead of Apollo 11. Surveyor 5 touched down just 25km (15½ miles) from the eventual manned landing site. During its brief operational life, the probe sent back 19,000 images and collected valuable data that would allow humans to follow.

Surveyor 5 touched own on the lunar surface in September 1967. It was not alone. Another spacecraft was waiting in the Sea of Tranquillity. Just over the horizon, about a day’s walk away lurked yet another emissary from a different time …

The Ranger 8 spacecraft was a still earlier mission to reach the Moon. It made a deliberate crash landing into the Sea of Tranquillity – making a mockery of that name – on 20 February 1965. The resulting crater and any remains of the craft are about 69km (nearly 43 miles) from the Apollo 11 site, but closer to Surveyor 5. One can imagine a ‘Lunar Heritage Trail’ connecting the three sites for 22nd-century tourists.

All in all, over 30 machines reached the Moon ahead of the Apollo 11 astronauts. Some were designed as landers or impactors, others were sent into lunar orbit, later to crash when their missions were complete. The very first object to reach the Moon – and a surprisingly little-known achievement these days – was the Soviet Luna 2 mission. It was deliberately rammed into the lunar surface on 13 September 1959, followed 30 minutes later by the impact of its carrier rocket. That’s another big stunner when you think about it. Stuff made by humans was sitting on the Moon a whole decade before Apollo 11 got there.

Incidentally, the total mass of all human artefacts on the Moon’s surface at the time of writing is something like 190 tonnes. That sounds like quite a junkyard, but it’s trivial compared with the amount of tech in Earth orbit. The International Space station alone has a mass of around 450 tonnes.

Among the famous quotes that will forever resonate through time – from ‘Et tu, Brute?’ to ‘I have a dream’ – one stands a quarter of a million miles above the others. No act in human history will ever compare with the first steps taken on the Moon. So long as our species exists, the name of Neil Armstrong, and his first words on the lunar surface, will be uttered with reverence. Such a pity that he may have fluffed his lines.

‘That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.’

This is what he was surely supposed to say. There he is, the lone individual chosen to take the most important stride in the whole wide history of sentient life, and what comes out of his mouth?

‘That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.’

For ‘man’. Not for ‘a man’. Neil Armstrong’s first words on the moon were a tautology. He’s there both for man and mankind, which is to say the same thing (at least if you accept ‘man’ as a synonym for ‘humanity’, an increasingly rare use of the word). Of course, Armstrong was doing one of the most important things that any human has ever done*, so we can let him off the tongue slip. Indeed, some have claimed that the garbled quote was all down to a glitch in the audio. This was 1969, after all. Getting a live audio stream from the Moon was at the bleeding edge of technology. Armstrong himself claimed not to remember whether he said ‘man’ or ‘a man’.

That ‘small step’ is also a little suspect. The lunar module was designed for a bumpy touch-down, with some serious shock absorbers built into the landing legs. The landing was more gentle than expected and the crumple zones did not compress. This left the ladder further from the surface than expected. Armstrong’s small step was actually a pretty long drop.

As a final blemish to the story, Armstrong’s famous quote might have accompanied the first steps, but it was not the first message from the lunar surface. That honour fell to Buzz Aldrin, whose voice was the earliest to be heard upon touchdown of the lunar module. His immortal words, the first to be spoken on any alien world, were simply ‘contact light’.

While we’re on the subject of duff quotes, there’s another famous one-liner from the Apollo program that most people get wrong. The calamitous Apollo 13 flight of April 1970 gave us the phrase ‘Houston, we have a problem’. It was brought to prominence by the 1995 Ron Howard film Apollo 13, starring Tom Hanks as commander Jim Lovell. The quote has been widely used and parodied ever since. We say it whenever we realize that our car is out of fuel, or when a toddler fills her nappy in a public place.

The real Jim Lovell, speaking over radio to capsule command, said something ever so slightly different: ‘Houston, we’ve had a problem’. The script writers changed it to the present tense for dramatic effect, and it went on to be voted the 50th best quote in American cinema by the American Film Institute. Actually, it goes back even further. A 1974 TV movie about the mission was similarly titled Houston, We’ve Got a Problem, and the phrase has cropped up sporadically ever since. But it was really the 1995 movie that cemented the misquote into popular culture. Apollo 13’s other big quote ‘Failure is not an option’, is often attributed to flight director Gene Kranz, but it too was made up for the film.

* FOOTNOTE Along with his more famous ‘first’, Neil Armstrong was also the first US civilian in space (though he had earlier seen military service) aboard Gemini 8 in 1966. During that mission, he also performed the first ever docking in space, and survived the first in-orbit emergency in US spaceflight when the craft began to roll. Buzz Aldrin, meanwhile, holds the record as the oldest person to reach the South Pole (of Earth), aged 86. The octogenarian had to be evacuated early due to illness. In a bizarre twist, the New Zealand doctor who treated him was called David Bowie, namesake of the ‘Space Oddity’ singer.

Neil Armstrong got the biggy, but many of the other Apollo astronauts can stake a claim to a lunar first. Let’s get the most important ones out of the way first …

First pee: Buzz Aldrin reckons to have beaten his colleague in attending to nature. The second man on the Moon was the first to urinate, a feat he achieved while climbing down the lunar module’s ladder. (It trickled into a pouch inside his spacesuit, in case you’re imagining him marking his territory.)

First poop: Posterity is silent on the first lunar poop. It must have happened. The later missions to the Moon spent three days on the surface. Even an astronaut can’t hold it in that long. Toilet predicaments are known (see here), but the faecal first is unrecorded. The Apollo astronauts certainly carried ‘defecation collection devices’ with them to the lunar surface. These plastic bags – 96 of them, if Internet sources are to be believed – were left behind, complete with astronautical deposits.

First puke: It’s not unusual for astronauts to become reacquainted with their lunch. The weightless conditions of space play havoc with the body’s balance systems, leading to an extreme version of motion sickness. The effect is much reduced on the Moon’s surface, which enjoys one-sixth familiar gravity. NASA medical records show that none of the 12 moonwalkers vomited. It might not be the most glamorous way to get yourself into the record books, but the title of First Lunar Vomiter is still up for grabs.

First food and drink: Buzz Aldrin (again) was the first to dine on the lunar surface. Following the successful landing of the Eagle, Aldrin signalled back to Earth that anyone listening in the control room should take a moment to reflect on the historic moment. He then produced a flask of wine and piece of bread to partake in Holy Communion. As he later reflected: ‘I poured the wine into the chalice our church had given me. In the one-sixth gravity of the Moon the wine curled slowly and gracefully up the side of the cup. It was interesting to think that the very first liquid ever poured on the Moon, and the first food eaten there, were communion elements.’ The first official meal, eaten by both Aldrin and Armstrong, was an astral buffet of bacon cubes, cookies, peaches and coffee.

Incidentally, Alan Bean did not consume any beans on the Moon, but he was the first to eat spaghetti. As he explained in a provenance note to an auction house: ‘I wanted to be the first human to eat spaghetti on the Moon as it was, and is, my favorite food. So I asked our food team to pack two first meals on the Moon for me. I ate one after Pete [Conrad] and I landed, and returned this same one back to Earth.’ The returned pouch was put on sale at auction for a minimum guide price of $50,000.

First golf shot: Alan Shepard already had some unique bragging rights. He was, after all, the first American, and the second human, to enter space during the 1961 Freedom 7 mission. A decade later, and he was back among the heavens in Apollo 14. While on the lunar surface, he became the only person (so far) to play golf anywhere other than Earth. Shepard used an adapted six iron to strike two golf balls into the distance. Nobody knows how far they arced in the low gravity of the Moon – probably further than any drive on Earth.

First song: Somewhat predictably, Frank Sinatra’s version of ‘Fly Me to the Moon’ was the first song to be played on the lunar surface, as chosen by DJ Buzz on Apollo 11. The same song had earlier accompanied Apollo 10 as they circled the Moon. Any musicians looking for long-term fame and a planet-sized royalty cheque should get to work writing ‘Hello From the Asteroid’ or ‘First Earthling on Mars’. The first astronauts to play musical instruments in space were Walter Schirra and Tom Stafford aboard the Gemini 6 mission in December 1965. The pair gave an impromptu rendition of ‘Jingle Bells’ to a bemused Mission Control, using a harmonica and bells they had smuggled aboard.

First scientist: Harrison Schmitt, on board Apollo 17, was the first and only Apollo astronaut from a scientific profession. As a geologist, he was well placed to identify unusual rocks for study and is indeed credited with finding some of the most important specimens. Schmitt was also the last man to step onto the Moon, on 11 December 1972. (His colleague Eugene Cernan was the last to step off the Moon.)

First wheels: Images of the later Apollo astronauts cruising around on lunar rovers are well known, but the US was not the first to spin up the satellite dust. The Soviet-launched robot Lunokhod 1 touched down on the Moon in November 1970, eight months before the first US vehicle. In 10 months of operation, it travelled around 10.5km (6½ miles). The first humans to drive on the Moon were David Scott and James Irwin in August 1971. They travelled 28km (17⅓ miles) around the Apollo 15 landing site in the first of three human-carrying lunar rovers.

First animal: No animals have ever landed on the Moon – unless some tiny insect managed to stow away undetected. This is not to say that humans are the only organism to visit our natural satellite. Countless species of bacteria accompanied the Apollo crews. Many would have been left behind in those 96 bags of bodily waste. Nobody knows how these first lunar colonies fared on their new home. When humans one day return to the Moon, these unglamorous relics will be high on the list of scientific targets.

First burial: Although nobody has ever died on the Moon, it does harbour human remains. Dr Eugene Shoemaker was a noted astronomer, famed for his work on lunar geology and co-discovering the Jupiter-striking comet Shoemaker–Levy 9. After his death in a car crash, colleagues successfully petitioned to have his ashes sent to the Moon. A sample of his remains was placed aboard NASA’s Lunar Prospector spacecraft. After a successful mission, the probe was deliberately crashed into the Moon’s surface on 31 July 1999. Shoemaker is the only human to be buried (or partially buried) on a world other than Earth.

Lunar rock is precious stuff. The six Apollo missions to land on the Moon collectively brought back about one-third of a tonne. The majority is locked away from public view in a special US government facility. The rest – tiny samples, really – were dispersed around the world in 1970 as gifts to various nations. These samples are literally as rare as Moon dust, and attractive targets for thieves. A staggering two-thirds of the gifted lunar samples are missing, presumed stolen.

The Apollo missions are, to date, the only human sojourns to the Moon’s surface. But lunar samples have found their way into Earth laboratories by two other routes. The first is a trio of Soviet landers called Luna 16, 20 and 24. These sophisticated but little-known craft visited the Moon between 1970 and 1976. Each was able to land robotically, drill into the rock, extract samples, stow material in an ascent stage, then fly home to a parachute landing. It was a remarkable achievement, and would be tough even with today’s technology. Even so, the three missions retrieved only about 300g (10½oz) of lunar material between them – about one-thousandth of the quantity returned by Apollo.

The third route for lunar rocks to reach Earth involves no human intervention whatsoever. Humans didn't land on the lunar surface until 1969, but the lunar surface has always been visiting us in the form of meteorites. Whenever a large rock or comet strikes the Moon – and there are abundant craters to show that this is not exactly rare – it smashes up a cone of debris. Gravity here is only one-sixth as strong as on the surface of the Earth. Much of the ejected material has enough velocity to escape the Moon and some rains down on Earth. The smaller chunks burn up in the atmosphere, but occasionally a lunar meteorite makes it through to the ground*.

Of course, it then has to be found and identified to be of any use. The Earth’s surface is littered with rocks, but meteorites do stand out to the trained eye. The fiery passage through the atmosphere leaves them with a distinctive surface called a fusion crust. The best place to spot a meteorite is Antarctica, where dark rocks contrast against the white landscape. Once collected, they can be distinguished from more common types of meteorite (which usually have origins in the asteroid belt) by chemical and spectroscopic tests.

Over 325 lunar meteorites are known, although many may be fragments of the same rock. They have an equal chance of originating from any given part of the Moon. There must be rocks in the collection from the far side of the Moon – our only source of such material. Sadly, there’s no way of knowing which these are.

The entire collection of lunar meteorites weighs about 177kg (390lb). If the Moon really were made of cheddar, that’d be enough for some 2,300 portions of mac and cheese. Even so, it’s still a long way short of the third of a tonne brought back by Apollo. If we really want to understand the Moon, we need to return and get digging.

* FOOTNOTE Meteorites from Mars are also known. One specimen, found in the Allan Hills of Antarctica, caused a furore in 1996 when scientists announced signs of microscopic fossils thought to be Martian in origin. Sadly, further studies cast doubts over the findings. Few scientists now support the notion that this Martian meteorite contains signs of ancient life. No meteorite has ever been identified from Venus. Although it gets closer to Earth than Mars, Venus is more massive and therefore has a higher gravity well for ejecta to overcome. It also has a thick atmosphere that destroys many impacting rocks, and slows down any rubble that is ejected.

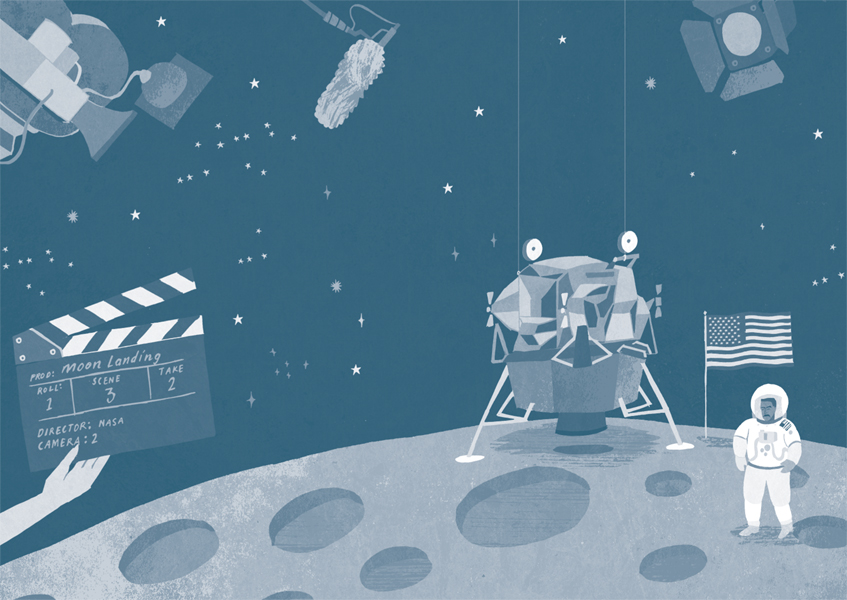

Humans have landed on the Moon six times. This is among the greatest achievements in history. It would be difficult to argue otherwise. Unless, of course, you don’t believe the Moon landings ever happened. Many do not. Conspiracists claim that humans have never been to the lunar surface and that the whole adventure was faked in a film studio*.

It’s easy to see where this lunacy comes from. Neil and Buzz hopped about on the Moon just eight years after the first human spaceflight. They got there with a computer millions of times feebler than a smartphone. More than this, the whole, dangerous venture was successfully repeated on five occasions without loss of life or serious injury. Surely it was all too good to be true?

Those who cry foul have put forward a suite of anomalies that ‘prove’ the Moon landings were an elaborate hoax. Their claims are intriguing, but easy to pick apart.

The American flags planted on the Moon appear to flutter, as if blown by the wind. But there is no wind on the Moon. It must be a fake!

Watch a video of any moonwalker planting a flag, and this statement begins to look interesting. The flag does indeed flutter, as though caught in a breeze. What’s going on? There’s a perfectly rational explanation. It flutters not because of wind, but due to an absence of air. The Moon flags contain wire to hold them perpendicular to the pole. After all, it’s a crummy flag that languishes in a perpetual droop. Poles and wires are very good at amplifying vibrations – consider the dubious practice of dowsing on Earth. Without any air to slow things down, that flag is going to wobble around while in the astronaut’s hands. It will continue to jitter after he has let go, again because there is no air resistance. That’s what we see in the footage. It’s not the wind. Besides, if the whole thing had been made in a film studio, why would there be a breeze blowing across the set? Did someone goof up and leave a door open … on six separate occasions?

The astronauts’ shadows fall in multiple directions, even though the Sun is the only light source. Meanwhile, astronauts standing in the shadows are lit up too brightly, as if studio lights were involved.

You can see these effects in any number of Apollo photographs. The shadows cast by astronauts, equipment and rocks often point in conflicting directions. Buzz Aldrin is photographed climbing down a ladder in the shadow of the lunar module*, and yet it’s easy to make out the detail on his moonsuit. How can we explain these mysterious umbra? The Moon’s surface is a pock-marked place, riddled with divots and hillocks. Slopes can play illusions with shadows, making them seem shorter or longer. It is quite natural for one shadow to fall at a different angle from its neighbour. These effects are easily re-created at home with a few pieces of cardboard, some pins and a spotlight.

It’s true that the Sun was the only light source, but its power to illuminate was magnified by reflections. On Earth, it’s possible to read by the light of the full Moon. If you swap positions, the light of the full Earth casts even greater illumination onto the Moon’s surface. Further, the mirrored material on the lunar module, and even the astronauts’ bright white spacesuits can also light up nearby objects by reflection. Computer modelling has since demonstrated that these reflections can indeed account for the anomalies identified by conspiracy theorists.

Where are all the stars?

None of the photographs from the surface of the Moon show any stars. With such clear, black skies, how can that be? Their absence proves that the landings were faked, say conspiracy theorists. NASA would have found it impossible to convincingly re-create the ever-shifting firmament on a film set, so they left it out.

All of the Apollo landings took place in daylight. The Sun never left the sky for any of the 12 moonwalkers. With this constant glare, and the reflective light from the ground, it is unsurprising that the stars were difficult to make out. Further, the mission cameras were set up to record the moonwalkers on the brightly illuminated surface. That needs a fast shutter speed. To capture the relatively meek light from the stars, a much longer exposure time would be required (try photographing the stars with your own camera on Earth). This would have ruined the shots of the astronauts.

The crews would have been fried by the radiation of deep space.

Radiation risk is one of the most popular objections to deep space exploration. The Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field cut out much of the energy from solar flares, cosmic rays and other forms of radiation. Travel too far outside these protective envelopes, and you’ll soon get fried.

Space radiation is a genuine concern. Missions to Mars will have to include shielding, or else risk the health of the crew. The greatest radiation threat to the relatively short Apollo missions came in a region of space known as the Van Allen belts, a bloated doughnut of energetic particles trapped by the Earth’s magnetic field. Nobody was entirely certain how exposure to this region might affect the crews. The best guess was that a quick whizz through the belts would not cause any lasting damage. And so it proved. The Apollo astronauts travelled through the Van Allen belts in a matter of hours, receiving a radiation dose similar to a hospital X-ray. None suffered any ill effects. Conspiracy theorists are right to point out the hazardous nature of the belts, but only to those who would linger for a few days.

No visible crater can be seen beneath any of the lunar modules – surely the retrorockets would have dug out quite a pit. And also, how come we don’t see any flames from the engine when the astronauts take off again?

The lunar module landed on solid rock, coated with a thin layer of dust. Its engine was not powerful enough to erode the rock – remember, the Moon’s surface has only one-sixth the gravity of the Earth’s, so rockets here do not need to be so muscular. Hence, no crater was made during landing or take-off.

Footage of that take-off from a remote-controlled camera on the Moon’s surface looks very odd. The spacecraft appears to spring into the air, as though pulled upwards by a wire. No flames are seen. Unsurprisingly, this has attracted the attentions of conspiracy theorists. The answer is simple. The engine uses an unfamiliar fuel mixture – hydrazine and dinitrogen tetroxide – best suited for the low-gravity environment of the Moon. This burns without visible flame. The astronauts are flying under rocket power, but we can’t see the exhaust.

Many other supposed anomalies and discrepancies have been raised by doubters over the years. All are explained with a little rational thought. The biggest objection to claims of hoaxed landings, for my money, is that to fake the missions would have been far harder than just to do them. Imagine how many personnel were involved in the planning and execution of the six landings. Surely a few of them would have spoken out by now. How come no organization like WikiLeaks has ever got hold of official documentation (and there must have been loads of the stuff to project manage on this scale) to show it was all faked? And crucially, why did the Soviet Union remain quiet on the issue? Its tracking stations and spy networks would surely have got a whiff of any hoax.

* FOOTNOTE Stanley Kubrick, who directed 2001: A Space Odyssey a year before the first Moon landing, is often implicated in the conspiracy. The mercurial director supposedly advised on the film set.

* FOOTNOTE It’s often claimed that there are no photographs of Neil Armstrong on the Moon, only of Buzz Aldrin. That’s not a conspiracy. It’s simply because Neil was the one with the camera, and selfies weren’t the trend of the time. It’s also not quite true. There are, of course, flickery video images of Neil stepping onto the Moon. Plus, a famous shot of Buzz in which you can see photographer Neil reflected in the visor.

Claims that humans never ventured to the Moon are at least understandable. The achievement is so magnificent, so daring, so exceptional that it would be strange if everybody did accept it at face value and there are plenty of other Moon conspiracy theories out there that are even more on the lunatic fringe.

Lost or hidden civilizations: Since time immemorial, humans have imagined that the Moon might be populated with other beings. A Greek manuscript from the 2nd century CE known as A True History describes a war between the King of the Moon and King of the Sun, complete with descriptions of the lunar realm. A 10th-century Japanese fable, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, concerns a visit from a Moon princess. As we saw elsewhere, The Man in the Moone (1638) by Church of England bishop Francis Godwin tells the story of a man pulled to the satellite by geese, where he finds a Christian civilization. There are many other examples, from many periods and cultures.

It is only in the past two hundred years, with the development of modern science, that the idea of Moon people has gone away. Well, not entirely. UFO enthusiasts and other creative thinkers still maintain that the Moon could be inhabited. These native Lunalings dwell deep in the craters and caves of our satellite, or are hidden from observation on the far side. Another bizarre theory holds that the Moon is actually hollow, and conceals a titanic alien space station. We can do another thought experiment here. Sit back and ponder the single most unlikely thing you’d expect to find on the Moon. Then Google it. Chances are that someone has already worked your idea up into a fully fledged conspiracy theory.

The first big case of inhabited Moon chicanery dates back to 1835. A New York newspaper called The Sun published a series of articles that describe observations of the Moon with a stupendously powerful telescope. A world of oceans, forests and habitations is seen through the instrument. Its lenses are so colossal that it can even make out creatures on the lunar surface. These include tiny bison and zebra, a blue-grey goat with a single horn, a spherical amphibian that rolls along a beach, and a tribe of bipedal beavers who have mastered fire. The Moon was also home to two intelligent species. One resembled a giant bat. The other was ‘scarcely less lovely than the general representations of angels by the more imaginative schools of painters’.

The dubious essays came, supposedly, from a colleague of John Herschel, one of the leading astronomers of the day (and discoverer of Uranus). The real perpetrators eventually admitted the fiction, later dubbed the Great Moon Hoax. They did, however, capture the popular imagination, and paved the way for any number of later deceits and delusions concerning life on the Moon.

Apollo 20: One of the more recent hoodwinks is known as the Apollo 20 hoax. In 2007, videos appeared on YouTube purporting to show footage from a secret mission to the Moon known as Apollo 20. According to the films and later interviews, Apollo 20 was a joint mission between the Soviets and Americans, launched in August 1976 from California (previous Moon missions had all flown from Florida). The spacecraft landed on the Moon as planned, and discovered the remains of an ancient civilization. The crew brought back artefacts, which included a hibernating humanoid.

It’s an intriguing tale, well told. It uses just the right amount of established fact and archive footage to weave a convincing tale. Alas, it is easily debunked. Many of the images are clearly from earlier Apollo flights. In addition, the first videos appeared on 1 April – April Fool’s Day – which doesn’t do any favours for the credibility. And, fatally, how could NASA have launched a Saturn V – the most powerful, noisy rocket ever successfully fielded – without any Californians seeing it?

YouTube and other video sites are riddled with such nonsense. A random dip finds gems such as ‘Japan offers proof of civilization on the Moon’, ‘Unknown “machines” discovered on Moon’ and ‘This is why we dropped nuke on the Moon! An incredible cover operation!’. Watch them at your peril.

Alien observation: ‘Does 40-year-old NASA film show UFO “observing” Apollo 15 Moon landing?’, reads a 2015 headline on Britain’s Daily Express website. ‘No. It is a hilltop’ is the immediate response any rational person would give after seeing the film. This is just one of countless images purporting to show an alien presence on the Moon during the Apollo landings. Conspiracy theorists hold that the Apollo astronauts and NASA staff were well aware of their extraterrestrial audience, but hid the fact from the public. The alien presence is the real reason we’ve not been back to the Moon since 1972. Trespassers will be vaporized.

The idea is fanciful, perhaps even a bit creepy, but it does have a kind of sci-fi logic. If interstellar civilizations exist, they may wish to keep a covert eye on our baby steps. A Moon landing would be an obvious observation point in our assessment. It marks the stage in our development when we became a multi-world species – an accomplishment that might have implications down the line for any stellar neighbours. The idea is commonly found in science fiction – most notably the ‘first contact’ rules in the Star Trek universe.

There is (obviously) no credible evidence to suggest that aliens watched any of the Moon landings. Plenty of non-credible evidence can be found online, though. An abundance of photographs show alien spacecraft on or above the Moon. The proof is there so long as you squint hard enough, or suspend your incredulity to the point of asphyxiation. It may be more exciting to attribute a light in the sky to aliens, but it’s much more likely to be a smudge or lens flare.

Some websites and ‘newspapers’ go still further and claim to have revealing eyewitness testimony from Neil Armstrong and other moonwalkers. Such interviews are always presented as transcripts. Where are the audio or video files of an astronaut vouching for aliens?

Lost cosmonauts: So triumphant were the Apollo Moon landings, it’s easy to forget that the Soviets had an advanced lunar programme that might easily have beaten the Americans to the prize. They had developed their own lunar spacecraft and a monster rocket known as the N1 which, unfortunately, malfunctioned on all four of its uncrewed test launches.

The Soviets were desperate to beat the Americans to the Moon, and it’s not wholly inconceivable that they might have risked a crew on this unreliable technology. You may recall the claims that other cosmonauts beat Yuri Gagarin into space, only to be hushed up following a disaster. Similar stories have been spun about the conquest of the Moon. In one version, a crew of two cosmonauts successfully flew out to the Moon in 1968 a few weeks before the Americans achieved the same with Apollo 8. Unfortunately, they failed to hit the correct return trajectory. Their craft shot beyond the satellite to head off into deep space. It was never heard from again, nor acknowledged by the Soviet Union. Andrei Mikoyan is sometimes named as one of the two cosmonauts to suffer this fate. Again, there’s no convincing evidence.

A variation has a crew of would-be moonwalkers seated atop an N1 rocket that launched on 3 July 1969. It is a matter of historical record that this rocket launch took place, though it was reported as uncrewed. Suppose that the Soviets took a gamble. They knew that the launch of Apollo 11 was imminent (it took place a fortnight later). Maybe, just maybe, they could pip the Americans to the post and get away with a crewed flight to the Moon.

There is no evidence for this, simply speculation. The N1 rocket exploded seconds into its flight. Spectacularly so. The resulting fireball is reckoned one of the largest non-nuclear explosions created by humans. Had any crew been on board, though, they may well have survived. The rocket included a launch escape tower, which propelled the capsule away from the blast zone. No cosmonaut has ever come forward with their tale of a miracle escape.

Stories like these are impossible to disprove without access to confidential files. Yet with only flimsy, circumstantial evidence, they must remain in the realm of urban myth until proven otherwise.

The astronauts aboard Apollo 13 are rightfully given credit for travelling further than any other humans. Their spacecraft, though crippled by an explosion, swung around the back of the Moon at a maximum distance from Earth of 400,171km (248,655 miles). No living human has been so far from home as Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert and Fred Haise. Yet if we stretch definitions a little – and, hey, it’s the end of the chapter, so why not? – there is one human who has travelled much, much further.

Clyde Tombaugh (1906–97) is most famous for discovering Pluto in 1930. At the time, it was considered the ninth planet, though it has since been relegated to a dwarf planet. He is also credited with discovering 15 asteroids and hundreds of stars, galaxies and clusters. This glittering career is reflected throughout the Solar System. A large crater on Mars bears the name Tombaugh, as does a range of cliffs in Antarctica. The famous heart-shaped planes on Pluto are known as Tombaugh Regio. And Tombaugh has one further accolade, yet to come: his will be the first human remains to leave the Solar System.

A sample of the astronomer’s ashes are on board NASA’s New Horizons probe, launched toward the outer Solar System in 2006. This tincture of Tombaugh flew past Pluto in 2015 and is now deep into the Kuiper Belt. He’s well on the way to being the first interstellar human, albeit in powder form.

The container holding Tombaugh’s ashes bears the following inscription:

‘Interred herein are remains of American Clyde W. Tombaugh, discoverer of Pluto and the Solar System’s ‘third zone’. Adelle and Muron’s boy, Patricia’s husband, Annette and Alden’s father, astronomer, teacher, punster, and friend: Clyde W. Tombaugh (1906–1997).’

One imagines, millions of years from now, the probe’s interception by an alien civilization. Their scientists shouldn’t have too much trouble working out where the probe came from or the kind of mission it had fulfilled. But imagine the heated debate about the word ‘punster’.