Call not that riches which may be lost; virtue is our true wealth and the true reward of the possessor. It cannot be lost, and will not abandon us unless life itself first leaves us.

—LEONARDO DA VINCI

I remember the joy I felt as a child, finding in the toe of my Christmas stocking a wonderful orange, almost too precious to eat. Or when someone brought a new record home, everyone eagerly listened to it. Now fruit and recordings are commonplace.

I want to live in such a way that small gifts are meaningful.

In a society that has too much material wealth, it becomes increasingly difficult to find a gift to give that is both simple and needed. Here in the wilderness, where everything has to be carried in by pack or by canoe, small things take on greater significance.

It is unfortunate that the word “wealth” has been coopted, so that in common usage wealth refers to money or to those things that money can buy—material possessions. To be successful is to be wealthy. Yet many people also feel that to be successful is to be fulfilled.

Is it possible to have too much material wealth?

And is it possible to have a life with too much leisure—as harmful as one with too much toil?

THE EXAMPLE OF THE RICH

Imagine a society of a thousand people each having a yearly income of $1,000 and living in poverty. Then imagine that one person in that community has an income ten times the average. If this money were divided evenly, it would mean only $10 more per year for each person. This 1 percent increase would help somewhat, but not a great deal. Although a fairer sharing of the world’s wealth is urgently necessary, merely redistributing monetary wealth is minuscule in importance compared with the need for intelligent, cooperative action aimed at improving the quality of life.

If wealth and fame do in the mind abide,

then naught but dust is all your yellow gold.

—FROM A CHINESE POEM

The wealth of the rich would not mean much if it were spread out evenly, but the example of luxurious living spread about is a time bomb.

The great evil of the rich is the example they set. Yet the power of the rich is very fragile, for their privilege cannot withstand the gaze of an enlightened populace. What good is their accumulated “wealth” if we refused to work for them? If we refused to accept their values and their way of life?

The trap we are in is that we want to emulate the rich. Their factories produce for us, and we are their buyers, the consumers. If we refused to buy junk, they would have to produce quality. A factory is a liability if its products won’t sell. They will produce whatever we demand. We have the control—though we don’t know it yet—whenever we decide to take responsibility: that is, when we become mature in our economic thinking and in the use of our purchasing power. The monetary power of the wealthy is a social disease that can be cured, but the remedy needs our help.

We now have a class of people living according to a consumption pattern that exceeds that of the monarchs of previous centuries and that is rapidly devouring the world’s finite resources. It might not matter, physically, if a few thousand people acted in such adolescent fashion, but when millions do, the effect will ultimately be catastrophic, with the added danger that more millions, seeing the example of the rich, will strive for this luxury as well.

That is our greatest danger now, and the crisis is approaching epidemic proportions. From this vantage point, the “voluntary simplicity” of Richard Gregg becomes more important than ever before. Is it possible that we, the people of the industrial nations, the leaders in the race to destroy the earth, could set the pace for a move in a positive direction? Can we meet the challenge?

It is well that thou givest bread to the hungry, but better were it that none hungered and that thou haddest none to give.

—AUGUSTINE

Whatever we do is watched closely by the poor of the world. Will we use our economic advantage for the good of humankind or will we continue to rob and to exploit?

We must search for ways to live that are within the grasp of all people. In this light, redefining wealth and riches becomes a primary challenge.

SUCCESS

If I stock up possessions at the expense of my neighbors, I commit robbery, for until there is enough for all, surplus is theft from those who don’t have enough. And if I say, “I am involvéd in mankinde,” and I express respect and care for the social body around me, my definitions of success are in conflict, because monetary success is opposed to the well-being of my social body.

We need to make clear our definition of “wealth.” The word has different meanings for different people, and we often use it to connote widely varying concepts.

It has been helpful to me to break the idea of wealth into three categories:

Destructive, violent, or false wealth

Destructive, violent, or false wealth

Neutral wealth

Neutral wealth

Creative, productive, or nonviolent wealth

Creative, productive, or nonviolent wealth

Destructive or violent wealth includes those possessions that enrich one at the expense of others. This includes monetary wealth and material possessions that are in such limited supply that by owning them we deprive others. This is exploitative wealth, usually acquired through competition, theft, warfare, or inheritance, and protected by the law with its threat of violence. Wealth of this kind is usually dependent on finite resources. Although masquerading under the title of “riches,” this kind of wealth is in reality poverty, in relation to our social body. An exploitative rich person restricts the flow of what is valuable instead of being a creator of wealth.

Neutral wealth comprises those possessions that neither help nor hinder other people. Under this heading I would place private learning (enjoyment of study for its own sake), things made for one’s own use, playing music for personal enjoyment, or collecting materials that are not in limited supply such as rocks, sea shells, or folk songs.

Creative or productive wealth includes all those possessions with which you enrich others. This includes knowledge that is shared, talents or skills that are used for the benefit of others, and those unique and wonderful realms of wealth wherein the more you give of them the larger grows your store. Chief among these are love and friendship, along with kindness and care, enthusiasm, health, and joy. Shared music is doubly enriching.

Creative wealth is nonviolent, based on sharing. To acquire this form of wealth no one need live on the back of another.

Each of us must ask, “What does the word success

mean for me?” We will need to do this repeatedly

if we are to live a life that does not exploit others.

To the extent that our daily life aids society as a whole

to succeed, we raise the base of our own individual

success or well-being. We need to move beyond today’s tawdry, shortsighted, destructive “success,”

which is cultural suicide.

GIVING

Perhaps it helps to approach such an emotionally loaded topic as wealth obliquely, to examine ways in which wealth affects us personally, in our daily lives.

What are your treasures? What are your jewels? What are the sources of your creative wealth? Contemplation of these questions is important to individuals and to society. Searching for your treasures and bringing them into the parlor of your mind can give great pleasure while helping to rid the world of a violent, destructive concept of wealth. With understanding, violent wealth can be made to disappear as a valid concept.

One facet of being rich is to be able to give gifts. No matter how much we manage to store up material possessions, if we are unable to give, we are poor.

What are the gifts that do not require a hoarding of possessions, that do not require the exploitation of others? The answer is things that cost little but are pleasing to both giver and receiver: a poem or a piece of music that we feel will bring pleasure; a shared meal, or a recipe; knowledge of a lovely spring, or a way to make shoes that are simple, beautiful, and comfortable; a gift of time, for helping plant an apple tree, dig a foundation, or care for a child.

The finest gifts depend on thoughtfulness, sensitivity, knowledge, and caring—not on the material wealth of the giver. Is there a finer gift than receiving a lovely person as a neighbor or friend?

FASHION

A more generous way of defining wealth requires rethinking many aspects of our lives: our dress, our homes, our way of living. Rather than rare paintings and china, why not fill our homes with the presence of joy, evidence of the search for wisdom, and signs of caring? Are not friendships and love the finest decorations a home can have?

It is the ancient feeling of the human heart—that knowledge is better than riches; and it is deeply and sacredly true.

—SIDNEY SMITH

Why accumulate when there is so much joy in giving?

—SHAKER EXPRESSION

Basket Case

The market in Tehuacan was bustling. As I edged through the early crowd, I was taken by a lovely basket passing on a woman’s back. It was heavily loaded, and she was small and old. Her hands held the tumpline at her temples to steady the load and to ease the strain.

I had been studying the crafts of Mexico for several years and was immediately taken by the beauty of this basket, which was more finely woven than any I had seen. Made of palm fibers, it was strong in a leathery way, with a subtle pattern worked into the weave that made you look twice to be sure it was really there.

Of course I followed the woman. She had arrived late at the market and was hurrying to get to her spot and begin selling her olives. When she was settled on her petate, kneeling with the basket of olives before her, I approached and tried to engage her in conversation. What followed was the strangest, most perplexing time I have ever had with a Mexican vendor. Usually they are affable, look you in the eye, and are extremely well at ease. On the contrary, this ancient one was shy, would not look directly at me, and spoke in monosyllables. Although frustrating, the situation was a challenge, and I was thoroughly enjoying myself.

Several times that morning, I returned to continue the “conversation.” This basket was just too beautifully made to give up on. I had to locate the source. The ladies on the neighboring mats were also thoroughly enjoying the show. They laughed and joshed this woman, who was old enough to be my mother’s grandmother, about her new boyfriend, making her more (if possible) uncooperative than ever.

“Did you make your basket?”

“No.”

“Will you sell it to me?”

“No.”

“Why not? I’ll pay you a good price.”

She ignored me. Then she offered, “If I sell it to you, I’ll have nothing to put my olives in.”

“I’ll buy you another basket and pay you for yours as well, so you can buy a nice new one when you get home.”

“No!”

I offered to buy all of her olives (though I hate olives).

“No!”

“But why?”

“If I sell you my olives I will have nothing to do all day.” (The neighbors were howling with delight.)

Finally we agreed upon a plan. She would sit all day and sell her olives. I would return at 5 P.M. and buy her remaining olives and her basket. By this time I learned that she as well as the lovely basket came from the village of Chilac—a bit lower down in the hot country than Tehuacan—where this special palm grew for weaving the baskets.

By the day’s end Doña Anna was relaxed and smiling. We had become friends.

Beware of activities that require new clothes.

—HENRY DAVID THOREAU

Simplicity in design and furnishings is a beautiful backdrop for human warmth.

On the other hand, fashion is a device to separate fools from their money, a snare to enrich merchants and producers. Do we need so much decoration in our lives? Can the world afford the expense?

Rather than be a follower of expensive fashions, why not be a leader in simple fashion? Be clothed in purpose, clarity, and kindness, and dress in a way that makes the best use of the world’s supply of materials. Thoreau admonished us to “know your own bone.” I would like to extend that to “wear your own clothes.” If they are of your own make and design, so much the better, but whether or not you make them yourself, wear the clothes you like best, those that have a special meaning. If all of us would do this, we would feel freer, we would walk more easily.

How much richer the visual atmosphere would be if we abolished the fashion of luxury and replaced it with the comfort and rich variety of modern expressions of folk clothing and furnishings.

Among our finest treasures are jewels of the mind—the potential to discover the myriad facets and depths of truth, whether in philosophy, husbandry, or design.

These are true treasures, with rewards that are

ever growing, enriching both individuals and society,

encouraging each being to develop

to fullest potential.

COVETING OR SHARING?

Hoarding is generally viewed as a sickness, a result of insecurity, and an expression of insensitivity to the needs of our fellows. How many of us are willing to face the fact that as a nation we are taking for our own use what rightfully belongs to others? As Americans we are generally proud of defending “liberty and justice for all.” But unless we see this “all” as including all the other people of the world, that becomes a narrow partisan slogan upholding an oppressive privileged class not very different from that which many of our ancestors sought to escape in earlier times in other countries.

A poor woman, having covered her children with all the rags and bits of cloth and carpet she could find, was accustomed to lay down over all an old door which had come off its hinges. “Ah, mother,” said the eldest daughter, “How I pity the poor children who haven’t got a door to cover them.”

—RALPH WALDO EMERSON

If we would each resolve to own no more than we ourselves can use and care for—be it land, clothes, tools, or toys—wealth would be more equitably distributed. If we need to hire someone else to care for our things, we own too much.

Some would argue that asking people to go without our accustomed luxuries would be a limitation on our freedom. But imagine eating only those foods that need few dishes to prepare and serve, instead of dining in a way that requires much more work for ourselves and others. The luxurious meal is not freedom at all, but the reverse. A simple meal can be most beautiful.

Simplicity is not just a personal, subjective approach to living, merely another fashion. Simplicity has long been recognized as a necessity by those aspiring to reach a higher plane of existence.

Violence is rooted in insecurity and want, and simplicity in living addresses both of these ills. By becoming involved in the shaping of things around us, we grow in self-confidence and knowledge with a resulting growth in security. By needing less ourselves, we make more of the world’s store available to those in want. Covetousness is reduced when we have simple things that others can easily obtain for themselves.

The simpler something is to make, the more easily it can be replaced and the less we are dependent on special skills, materials, or markets. So simplicity is not just a matter of doing more with less, or spending less, or using less of the world’s resources; it is a matter of freedom.

Until there are enough of the basics of life to go all the way around, it seems to me that we have an obligation to use our time, knowledge, and resources in ways that promote human growth. Giving a family a loaf of bread feeds them now, one time. Teaching them to raise wheat on land of their own feeds them permanently and makes them more self-respecting and self-sufficient. One gift beggars, the other builds a basis for a strong society.

WEALTH WITHOUT POVERTY

The condemning factor in the traditional definition of wealth was that there could be no riches without poverty. Like the two sides of a coin, one was necessary to have the other. The rich needed the poor for contrast, as a foundation for status, and to do their work. This is an explosive definition of wealth, containing within it violence and warfare.

It is crucial that we begin defining as wealth only those possessions and activities that do not make another poorer, that diminish no one. To build a society in which all are free to develop to their fullest, we must learn to enjoy the satisfactions of shared accomplishment, wherein we gain pleasure from what we achieve, rather than I.

Simplify your needs to the point where you can easily satisfy them yourself, so that those who live for the spirit do not add to the burdens of other men, taking away from them perhaps the very desire to develop the spiritual life also. What will it benefit if, in developing your spiritual life, you add to the burden of others and if in rising you oblige someone to descend correspondingly in the opposite direction. You will simply have increased a state of inequality and injustice.

—PIERRE CERESOLE

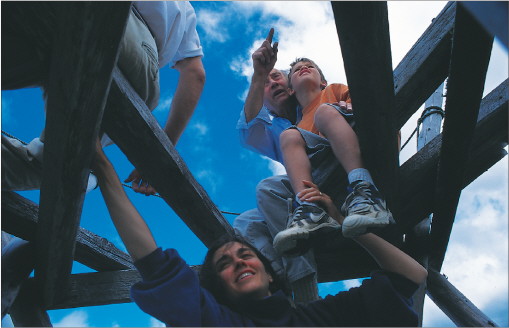

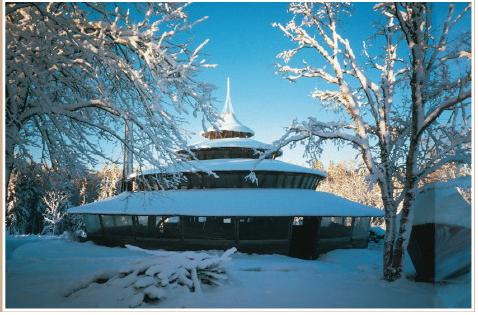

The Cost of a Home

The home you invest your time, energy, and money in should be one you prefer aesthetically—one you feel happy in. Only if the beauty of a curvilinear design excites you would I recommend building a yurt. The really big savings in these designs do not result from the elimination of rafters and corners, but from doing the design and construction work yourselves and from selecting materials that will be attractive when left exposed and finished simply with wax or oil. A paint-free exterior saves money and labor as well as future costs, including all the scraping to which you chain yourself as soon as you slap on that first dramatic coat of paint.

W. Coperthwaite

The approach of using low-maintenance materials can, of course, be applied to many other types of house besides a yurt, which reinforces my advice that the choice of a radically different form of structure to live in should be made from an aesthetic position—the feeling of pleasure you gain, living in the space—rather than just counting dollars saved during construction.

The design for a Family Yurt was developed to meet the needs of those who wanted a larger building than the Concentric Yurt. This design consists of a concentric yurt raised one story with another ring built around it, 53 feet in diameter, with a combined area of 2,700 square feet. My goal was to design this structure so that it could be built in stages to allow a family to start out with a very limited outlay of money, time, and energy, then expand the building as their resources grew. I aimed at an initial budget of $3,000. This figure would permit many people to bypass a mortgage, avoiding the usurious rates of the money lenders as well as their veto power over the design and time frame, with accompanying coercion to build a more expensive building than needed. As the stages of the larger design became more clearly defined, it evolved that the 16-foot-diameter central chamber could be begun with only $1,500 (in 1989) in cash. This central “hat box” of a room can be lived in until resources become available.

The second stage involves building a concentric yurt on top of and around the original room. The third stage is the construction of a large, sheltering roof spanning the outer ring. By putting layers of crushed stone underneath as a base, this area can serve as a porch, a garage, or a work and play area, and then, as additional rooms are needed, the outer ring can be enclosed with walls and floors.

There are many pressures on us to have our houses completed by the time we move in. The economic costs of this, as well as the resulting stresses in personal and family life, are tremendous. Why not take several years—or a lifetime—to create your home? Many of our most beautiful old houses were constructed over decades of building, and in the case of most farmsteads, over generations. Maybe we can learn an important lesson in this regard from the wisdom of our ancestors: an Asian proverb observes that a man is dead the day his house is finished.

As we become more sensitive to that social body of which we’re a part, we can plainly see that our neighbors’ lack is our own impoverishment.

Louisa May Alcott grew up in a household with few material goods to spare; her mother took in washing to make ends meet. Yet looking back to her childhood she remarked, “I thought we were rich, as we were always giving to the poor.” What a wonderful atmosphere for a child to grow in!

A wise, mature, and happy populace is our greatest natural resource. Each of the world’s children that dies prematurely—from illness, malnutrition, violence, or neglect—is a precious treasure lost from the world’s store. Even the most shortsighted and callous of us must realize that we need all the wisdom and talent we can muster if we are to solve the problems facing the world, and that it is stupid and dangerous to have malnourished, unhappy, stunted people as neighbors.

While the world hungers for knowledge of

how to build, raise food, and effectively organize

society, we turn our mature minds out to graze:

to retirement. In many fields the years from sixty on

are the richest in skill, perspective, concern,

and wisdom.

We are shocked by a businessman who wastes capital

or a farmer who lets topsoil wash away; why are we

less concerned with the waste of our human capital, our most valuable resource?

NOT LOSING BUT WINNING

We are accustomed to thinking in game terms, of winning and losing. We need to develop a philosophy of life in which there are no losers, a world where everyone can win.

Wealth can help us to do what we want, or help us to develop more fully. But often what is more valuable than financial power is an ability to recognize what is relatively most important. For instance, to me, a shower is an important adjunct to creative thinking, on par with a library. Likewise, finding just the right axe or hoe can be so essential to some people that they spend a good deal of effort in finding the one that suits them. This can be as satisfying as seeking out the latest style of car, yet costs the world much less.

“Success” is an increase in well-being, and “wealth” is the acquiring of creative, productive ability. In the past, success has generally been relative and competitive—measured by the failure of others. It now behooves us to think in terms of cooperative success, wherein we feel happy as the group about us succeeds. After all, what does it gain us to be “successful” in a failing society or, as J. Goldsmith has said, “To win in a poker game on the Titanic”?

I reckon—when I count at all—

First—Poets—

Then the Sun Then Summer—

Then the Heaven of God

And then—the list is done—

But Looking back—the First so seems

To Comprehend the Whole—

The Others look a needless Show—

So I write—Poets—All

—EMILY DICKINSON

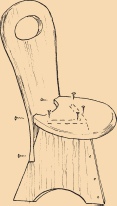

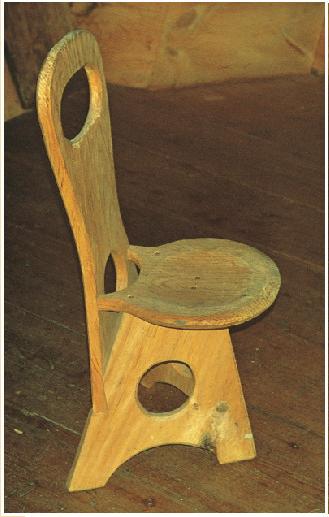

A Democratic Chair

Is there such a thing as democratic furniture? If so, what would a democratic chair look like?

W. Coperthwaite

Most of the fine chairs we see today, if handmade, take nearly as much skill as boat building and, if made with power tools, require much investment in equipment and acquiring the skills needed. I would like to see what those who are reading this might come up with for ideas for a handmade chair that is light, comfortable, strong, beautiful, simple to make from easily found materials. (All we seek is perfection.)

Utopian? Or impossible, to create an egalitarian chair? Not at all. As a society we have simply not yet focused on this problem. When we do, there will be some elegant chairs as a result (or boats . . . or houses . . . or wheelbarrows . . . (not necessarily in combination—although, come to think of it, there have been some very comfortable wheelbarrows, some very fine houseboats, and several wheelbarrow boats. . . .)

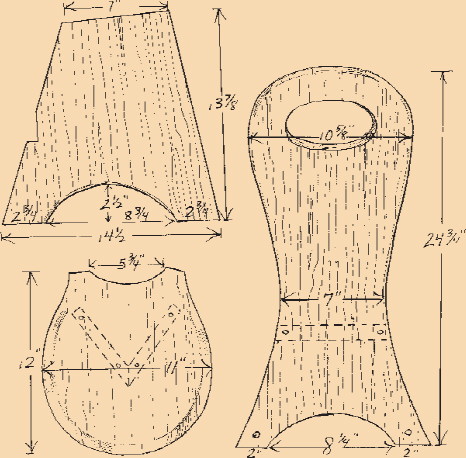

My suggestion for the most democratic chair follows. This is not provided to represent an ideal but in hopes of stimulating even better designs from you, the readers.

To Make the Democratic Chair:

1. Saw and whittle out the four pieces shown in diagram, using white pine 7/8-inch thick.

2. Bevel the front edges of the two base pieces to meet at the angle shown, then nail together.

3. Fit seat in place, and screw to the base with four screws.

4. Place the back piece in the notches in the base, and screw to the base and the seat.