The main thrust of my work is not simple living—not yurt design, not social change, although each of these is important and receives large blocks of my time. But they are not central. My central concern is encouragement—encouraging people to seek, to experiment, to plan, to create, and to dream. If enough people do this we will find a better way.

These are the words of Bill Coperthwaite. This book is about his lifelong commitment to living in a way that can create a world of justice, beauty, and hope.

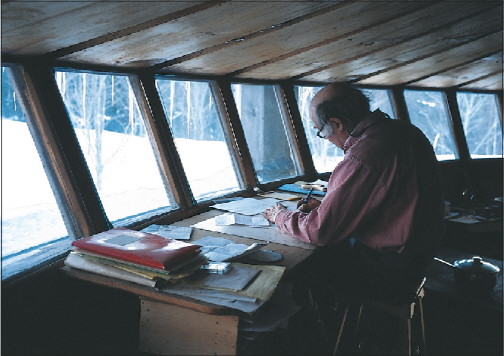

Bill Coperthwaite has spent better than forty years on a homestead in the wilds of Maine. He has also traveled the globe in search of cultural skills, practices, and designs that can be blended and enhanced for contemporary use. He builds as much for joy in the process of building as for the beauty of the result. He is as devoted to working with his hands as he is to the highest ideals of democracy. He lives on the furthest margins of the market economy as an experiment in sustainable living.

Several themes anchor his life practices: education, nonviolence, simple living, democracy, and the fallacy of discipleship. Bill has developed his thinking in detail around each of these, yet they are interrelated and mutually reinforcing, and my attempt to give each area separate attention for the sake of clarity must oversimplify.

Bill’s thoughts and actions have been profoundly shaped by those he describes as “people in particular whom I admired for their intellectual acuity, their work with their hands, and their dedication to a better society”—men such as Morris Mitchell, Richard Gregg, and Scott Nearing. Each of them influenced Bill in specific ways as he set his own course. He has neither followed nor looked to be followed, yet his way of being in the world embraces the linking of past, present, and future, providing a sense of irrefutable hope and abundant optimism.

EDUCATION

Bill’s undergraduate years at Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, Maine, proved uninspiring. Real learning took place elsewhere, out of the classroom and away from campus. He read Gandhi on his own. He established connections with the International Student Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts, jumping a bus to spend weekends discovering a wider world than the one offered through “higher” education. A senior semester abroad at the University of Innsbruck stimulated a yearning for culture and perspective; he became an expatriate who reluctantly returned to Bowdoin to complete a degree in art history.

Through connections in Cambridge, he was invited to apply for graduate study by Morris Mitchell, the director of the Putney Graduate School of Teacher Education. Mitchell, renowned for his “slow moving, bold thinking” presence, had come to Putney with a reputation as a tenacious southern Quaker and visionary organizer of school-based rural cooperatives in Alabama and Georgia. His Quaker faith and experiences as a soldier in World War I had made him a resolute pacifist. As an educator, he embraced experiential education and the application of knowledge for social purposes. In Mitchell, Bill found a mentor who “blended cabinet-making and gardening with his leadership of the school.” The students at Putney Graduate School were apprentices to a special view of education and the role of the teacher. “The life of a teacher,” Mitchell instructed, “is as important a life as any person may live. Viewed broadly, it is a life of leadership in a world of contradictions and crisis. It is a particularly human life, one of total involvement with human beings as they face human questions.”

Mitchell’s students, and the future students they would teach, would need to possess certain kinds of knowledge, but he believed that knowledge alone was not sufficient; they would not be true teachers “unless they become also intelligent in the art of democratic living in a day of peace based on universally shared plenty.” Mitchell was the first person who encouraged Bill to pursue his ideals and to put them into practice in his daily life.

Mitchell also modeled how a teacher may be both educator and learner. Not an authority of specialized knowledge, an expert who has all the answers and imparts some construction of “truth,” the teacher is a designer of the learning process, a choreographer of discovery. Teachers value and respect the unique knowledge that others contribute to the learning experience and foster a mutually shared responsibility among all those involved in producing knowledge and learning. This ethos of education is the precursor to active participation in civic life and the training ground for an expansive practice of democracy. Neither education nor democracy is a passive experience, a spectator activity.

Traditional education, in Bill’s view, puts children “behind a desk and make[s] them stay quiet and inactive for long periods of time from very early years, insisting that they learn material that is unrelated, for the most part, to their lives in any way they can see.” To remedy this, he believes schools need to provide for “excitement and physical challenge through work and through living close to the natural forces of wind and sea.”

Bill’s educational ideal celebrates nonviolence and sets students free from dreary inactivity. What is often lacking in educational programs dedicated to nonviolence “is the need for excitement, physical challenge, danger, and the feeling of camaraderie or esprit de corps that these bring when experienced as a part of a group.” In the past, Bill explains, “war has provided this, as has the imminence of natural disaster in the form of storms, floods, etc., and to some degree sports such as football, boxing, or mountain climbing. Those who are searching for a nonviolent life tend to move toward the elimination of all these (with the exception of sports that do not involve bodily contact) and put little in their place.” If it is to capture the imagination and attention of youth, education has to be “more challenging, exciting, and meaningful,” expressing elation in the activities of everyday life and a learning process relevant to that life.

This is the philosophy behind the school that Bill envisioned creating in Maine. In a letter published in the magazine Manas in 1963, he outlined his guiding educational principles in this way:

The school will adhere to Gandhi’s admonition that the more money involved, the less development there will be.

The school will adhere to Gandhi’s admonition that the more money involved, the less development there will be.

Education is the right of every child in the world, so schooling should be free to all who want to learn and are willing to work for the opportunity.

Education is the right of every child in the world, so schooling should be free to all who want to learn and are willing to work for the opportunity.

The instructors at the school will work with their hands and back as well as with their heart and brain to build the school and work for social change through the betterment of education, serving without financial gain.

The instructors at the school will work with their hands and back as well as with their heart and brain to build the school and work for social change through the betterment of education, serving without financial gain.

Education will be more challenging, enjoyable, and exciting while providing more opportunity for contemplation and solitude.

Education will be more challenging, enjoyable, and exciting while providing more opportunity for contemplation and solitude.

Aesthetics are central to the curriculum, since beauty is a birthright and the lack of beauty is a sign of great danger.

Aesthetics are central to the curriculum, since beauty is a birthright and the lack of beauty is a sign of great danger.

Feeling useful and needed is essential to sound emotional growth.

Feeling useful and needed is essential to sound emotional growth.

There is joy in hard physical labor.

There is joy in hard physical labor.

A close personal relationship with the natural world is of primary importance in the development of the individual.

A close personal relationship with the natural world is of primary importance in the development of the individual.

Every person has creative potential that should be nourished and helped to flower.

Every person has creative potential that should be nourished and helped to flower.

Students should be invited to learn and not compelled, as learning at its best stems from the request of the student and not the demand of an authority.

Students should be invited to learn and not compelled, as learning at its best stems from the request of the student and not the demand of an authority.

The development of skill with hands is of primary importance to full emotional and intellectual growth.

The development of skill with hands is of primary importance to full emotional and intellectual growth.

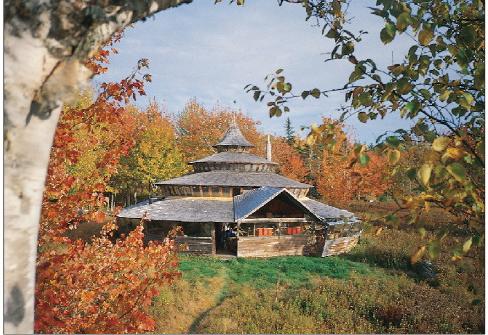

At one time Bill dreamed of creating this school on his own homestead on the coast of Maine. In some ways he has, although what now exists as the Yurt Foundation lacks conventional academic structures and organization. And there is no incoming or graduating class.

Build a yurt with Bill and you witness his educational ideas in action. The yurt is his philosophy made visible—security, nonviolence, simplicity, experimentation, activism, cultural blending, reverence for place, and beauty. He will not build a yurt for you (that would be tantamount to commodification of an educational experience), but he will work with you to build a yurt. As the structure takes shape, Bill emerges from the central hole in the roof and instructs those who are trimming and nailing shingles for the roof. There is a constant banter of cajoling, prodding, encouraging, and modeling. He could do it himself more quickly and with greater precision. But the yurt isn’t what is most important; rather, it is the learning that takes place in those who create a new shelter. The completed yurt is a delight of functionality and beauty.

The yurt also represents a key element in Bill’s educational philosophy: that the highest forms of knowledge combine wisdom from many different cultures—all the more essential now that knowledge, skills, crafts, and arts are being threatened as local cultures are destroyed. “Cultural blending,” he states, “ has been an operating force in human affairs since one tribe first met with another. . . . If it should be true that folk wisdom is our basic wealth, the chief insurance of a culture, then we are nearly bankrupt. This knowledge is disappearing at an accelerating rate. . . .We need to be collecting as many examples as possible of the old knowledge and skill, before they are forgotten and lost forever.”

W. Coperthwaite

At Bill’s homestead, cultural blending is embedded in his life practice. He explains:

My house has its origins in the steppes of Asia. My felt boots came by way of Finland from Asian shepherds. My cucumbers came from Egypt, my lilacs from Persia, my boat from Norway, and my canoe is American Indian. My crooked knife for paddle making is Bering Coast Eskimo, my axe is nineteenth-century Maine design, and my pick-up is twentieth-century Detroit. We are a cultural blend.

NONVIOLENCE

In the summer of 1955, when he traveled to Mexico as part of his graduate study, the disparate ideas that Bill Coperthwaite had encountered as a student crystallized into a specific vision of education and a way of living. “Things came together,” Bill recalled, “when my appendix ruptured.” A long hospital stay and recovery in Mexico allowed him to step back from his searching to reflect on all he had learned and encountered. Bill recalls:

There was absolutely no way, that I could see, that society could avert catastrophe. Everywhere there was pollution of air, water, minds; everywhere there was crime, poverty, political corruption, war, land and food poisoning. . . . I viewed the mass of humanity as easily duped, with people willing to sell themselves for material gain, while remaining provincial and violent. Democracy had become a system in which the many were manipulated by the few. Yet slowly it became clear to me that the basic human stock was sound and that the “democracy” I saw was not democracy but a distortion of it. As I became aware of our untapped potential as human beings, I began to grow in optimism and belief in our latent ability to solve problems. . . . Only a minute percentage of our abilities has been developed. . . . [I was not] concerned with what economic, political, or social system is best. I [was] concerned with education—the development of human beings, their growth.

During the Korean War, Bill claimed conscientious objector status. For his alternative service, he was assigned to work with the American Friends Service Committee, which brought him back to Mexico. During this time Bill discovered the writings of Richard Bartlett Gregg (1885– 1974). Gregg, a key figure in American pacifism, articulated a life practice of nonviolence connected to an expansive definition of democracy. “It was he who brought me closer to natural living, to Gandhi’s work, to nonviolence, to simplicity. When I was hard put to find support for my beliefs, he encouraged me.”

Bill found in Gregg’s work reinforcement for his own application of philosophy to personal practice. As Gregg wrote in The Power of Non-Violence, and in the pamphlet that accompanied the book, Training for Peace (1937), “Non-violent resistance is not an evasion of duty to the state or the community. On the contrary, it is an attempt to see that duty in its largest and the most permanent and responsible aspect.”

Richard Gregg had trained as a lawyer in the early years of the twentieth century and graduated from Harvard Law School. He spent a number of years teaching and practicing corporate law before focusing his attention on industrial relations. In 1921, Gregg represented the Federation of Railway Shop Employees during a nationwide strike, an experience that shook his faith in the ideals of American democracy and led to his reconsideration of labor and class relations. During the strike he also encountered the writings of Mahatma Gandhi. As Gregg later described the moment, “At the height of the nationwide American railway strike of 1921, when feelings were most intense and bitter, I happened by pure chance to pick up in a Chicago bookshop a collection of Mahatma Gandhi’s writings. His attitudes and methods were in such profound and dynamic contrast to what I was in the midst of then, that I felt impelled to go and live alongside of him and learn more.”

Gregg left the United States for India in 1924 and would not return for four years, spending seven months at Gandhi’s ashram. He studied Gandhi’s philosophy and its application in all aspects of life. Gregg was the first American to popularize nonviolent resistance in the United States. While Gregg’s influence is largely overlooked today, his writings were enormously influential in translating nonviolent resistance into modern Western concepts and terminology. The Power of Non-Violence was a handbook for resisters in the civil rights and peace movements of the 1950s and ’60s and directly shaped the thinking of leaders in these movements. Martin Luther King, Jr., wrote to Gregg in 1959, “I don’t know when I have read anything that has given the idea of non-violence a more realistic and depthful interpretation. I assure you that it will be a lasting influence in my life.” The imprint of Gandhi’s influence on Bill Coperthwaite can also be found along the path that runs through Gregg.

By the early 1950s, Gregg had relocated to Jamaica, Vermont, and become a close friend of economist and social activist Scott Nearing, who along with his wife, Helen, would become one of the leaders in a nationwide “back-to-the-land” movement. Gregg and Scott Nearing shared many interests and causes, and friendship was a natural outcome of their radical ideas and politics. With Nearing’s help, Gregg built a small stone cabin high on the slope in the sugarbush behind the Nearings’ homestead.

This was before the publication of Scott and Helen Nearing’s book, Living the Good Life (1954), and Bill Coperthwaite would not encounter Nearing or his writings for years to come.

“I am concerned,” Bill wrote, “as to how we can apply the Gandhian concept of nonviolence to life in this society. At the same time I am troubled that we tend to hear only Gandhi’s words on nonviolence and fail to read the next line or page, which says that it is only one part in a complex of things, that there can be no nonviolent society without bread labor, decentralization, voluntary poverty, and the development of the whole person.” In Bill’s reading of Gandhi, this framework of nonviolent democracy also compels each of us as an American citizen to accept global responsibilities. “In this country we have a tremendous responsibility to the rest of the world,” Bill counsels, “for whether we like it or not, and whether loved or hated, as the case may be, the world at large is following our lead toward greater industrialization, urbanization, and mobility, with the increasing impersonalization of life that these bring. We are obliged to find a way of life worth following, a way that encourages the best in man to unfold.”

Gregg’s The Power of Non-Violence resonated so strongly with Bill that he wrote to the author, initiating a correspondence that led to a lifelong friendship. He even hitchhiked from Mexico to New York and Gregg drove from Vermont to pick him up. Bill reflects, “We first met [when] I was twenty-five and he was nearly seventy. In his writing I had found a kindred spirit and so sought him out to thank him. It turned out [to be] a joyous event. Age difference seemed of no consequence. It was exciting to find that this gentle, white-haired man, with such wide knowledge of the world, had long before discovered many of the things that I was finding true in my world—the joy of bread labor; the importance of hands in education; simple living; the wonders of the technology of early peoples; and the relationship of these to nonviolence.”

Richard Gregg (left) and Scott Nearing at Jamaica, Vermont, in the early 1950s. (Photo by Rebecca Lepkoff, courtesy of The Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods.)

After finishing his alternative service and teaching for two years at North Country School, Bill headed south again in 1959, to Venezuela this time, to work on a rural development study for the Venezuelan government. When he returned to the States in 1960, he bought land in Maine, near the town of Machias, along the furthermost northeast reaches of the coast. He spent two years teaching at the Meeting School in Rindge, New Hampshire. He traveled to northern Scandinavia to study village culture and crafts, spending two years living among the Lapp people and learning their culture.

In 1966, Bill drove from Maine to Alaska to visit Eskimo villages and study their handcrafts and tools. During that trip he conceived the idea for a museum of Eskimo culture that would travel from village to village so that youth would be exposed to the arts and traditions they were rapidly losing. He submitted this project to the doctoral program of the Harvard Graduate School of Education and completed his dissertation about his Alaskan work.

SIMPLE LIVING

For Bill Coperthwaite, the practice of simple living has economic, social, and political implications. In this dimension, Bill was to find co-conspirators in Scott and Helen Nearing, who had commenced a more than fifty-year experiment in self-reliant homesteading and simple living.

Before leaving Depression-era New York City to move to Vermont, Nearing had spent decades developing a clearly defined personal philosophy and expressing it through active political dissent and protest. He wrote pamphlets and made speeches, engaged in civil disobedience, and ran for public office. He endured arrests, legal persecution (he was indicted under the Espionage Act in 1918), and firings (from two universities). Nearing was the embodiment of an extreme and pure form of noncooperation, living according to deeply held moral beliefs and exemplifying the position that how one lives is fundamentally a political act.

Nearing’s politics of simple living are rooted in his early life as an economics professor at the University of Pennsylvania—from which he was fired in 1915 for denouncing child labor and advocating the redistribution of income—and elaborated in his subsequent efforts to be financially and materially self-sufficient as a homesteader. At the heart of Nearing’s pursuits is the principle of non-exploitation and a commitment to social justice. Outrage over the exploitation of children that Nearing expressed in his 1911 book, The Solution of the Child Labor Problem, finds a corresponding expression, decades later, in a carefully developed practice of simple living that assiduously avoided exploitation of humans, animals, and the land. The Nearings created a way to live out their ethical and political logic through pacifism, vegetarianism, and environmentalism. As Scott and Helen wrote in Living the Good Life (1954), “We desire to liberate ourselves from the cruder forms of exploitation; the plunder of the planet, the slavery of man and beast, the slaughter of men in war, and animals for food.” The Nearings’ half-century of homesteading represents not an “exit strategy” from the complexities and contradictions of American culture, but a means of actively provoking genuine social change.

Bill Coperthwaite did not meet Scott Nearing until 1963. He avoided visiting the man about whom he had heard so much from Morris Mitchell and Richard Gregg, and whose books he had devoured, because he knew that the Nearings were inundated with visitors and seekers. It wasn’t until Bill had published his letter in Manas magazine describing an alternative design for a school that he received a letter from Scott inviting him to the Nearing homestead in Harborside, Maine. They became good friends.

Bill Coperthwaite was drawn to Nearing’s complex understanding of simple living, stressing the vital connections in everyday life between public and private, individual and community, personal and political. Bill also admired this teacher who, like Morris Mitchell, worked with head as well as hands, connecting theory and practice, nature and culture, human and nonhuman, labor and leisure, intellect and spirit, knowledge and ethics.

“Each time we learn to live more simply,” Bill explains, “we aid the world in two ways: (1) We use less of the world’s resources for our own life; (2) We help set an example for others who are now striving to copy the affluent life of their neighbors. The greater the striving for affluence, the more wretched will be the poor, and the greater will be the chasm between the haves and the have-nots. Violence will be inevitable. . . . Not only do we need to simplify in order to be able to share more of the things the world needs, but we need to distribute power, authority, and freedom as well. The more decentralized we become, the more opportunity will there be for individual decision-making.”

DEMOCRACY

Bill Coperthwaite defines democracy as active participation and active experimentation. He finds hope for the flowering of democracy in the possibility that each individual can regain agency in his or her own life. But agency and experimentation for what? The promise of democracy can be betrayed by savage inequalities that mock the highest ideals. In a false democracy, individuals become only spectators to their own experience and to the wider intellectual, civic, and social life around them. “The work of creating a new society” can only be accomplished, according to Bill, through citizen action; not “by specialists, but by the people themselves to fit their needs.” Only with “the encouragement to all people to take part” in exercising their “rights and obligations in designing the work of the future—discovering that their efforts are truly desired and needed—only then can a true democracy exist.”

Bill’s life represents a determined refutation of a culture of retreat. The widespread retreat from participation and direct experience tends to limit political action to a narrow definition of procedural democracy, the so-called electoral-representative process. This retreat makes protest, direct action, and mass involvement increasingly unlikely and ineffective.

Bill sees democratic action as that in which private behavior is recognized to have civic consequences. Here is a way of life that continuously asks the question, “How can I live according to what I believe?” Wendell Berry has described this kind of politics as “more complex and permanent, public in effect but private in its implementation.” According to Berry:

To make public protests against an evil, and yet live dependent on and in support of a way of life that is the source of the evil, is an obvious contradiction and a dangerous one. If one disagrees with the nomadism and violence of our society, then one is under an obligation to take up some permanent dwelling place and cultivate the possibility of peace and harmlessness in it. If one deplores the destructiveness and wastefulness of the economy, then one is under an obligation to live as far out on the margin of the economy as one is able: to be as economically independent of exploitative industries, to learn to need less, to waste less, to make things last, to give up meaningless luxuries, to understand and resist the language of salesmen and public relations experts, to see through attractive packages, to refuse to purchase fashion or glamour or prestige. If one feels endangered by meaninglessness, then one is under an obligation to refuse meaningless pleasures and to resist meaningless work, and to give up the moral comfort and the excuses of the mentality of specialization.

In his book about the lives of homesteaders Harlan and Anna Hubbard, Berry tells a story of the politics of personal responsibility exemplified by Bill Coperthwaite, as well. In the mid-1970s, across the Ohio River from the Hubbards’ homestead on the Kentucky side, Public Service Indiana began constructing a nuclear power plant. Berry joined with others who were concerned about the environmental impact of the plant. They organized protests, demonstrated, wrote letters, and engaged in a nonviolent sit-in at the site. Construction of the plant was never completed.

The Hubbards, to Berry’s initial disappointment, never took part in the protests, never signed a letter, never spoke out. Yet in rethinking his understanding of their political impact, Berry realized that “by the life they led, Harlan and Anna had opposed the power plant longer than any of us. . . . They were opposed to it because they were opposite to it, because their way of life joined them to everything in the world that was opposite to it.” As Berry asks, “What could be more radically or effectively opposite to a power plant, than to live abundantly with no need for electricity?” Berry’s realization is illuminating as we consider the life of Bill Coperthwaite.

Bill lives close to the land in a forested coastal area of eastern Maine, heating with wood, eschewing grid electricity and plumbing and motors, and experimenting with nonviolent crafts and cultural practices. His democracy of one is not lived for himself alone. Bill has undertaken his way of life as an experiment that can have resonance for others, offering possibilities for a truer democracy in the future.

THE FALLACY OF DISCIPLESHIP

Defining democratic life as a process of direct individual experience grants extraordinary significance to the importance of experimentation. There is no blueprint, no formula, and no set answers. Such a process of dynamic experimentation needs to be rooted in a specific place to be viable. In Bill Coperthwaite’s life, that place is a coastal forest with a cleared meadow that sweeps down a slope marked at one end by a three-story yurt and bounded at the other by the water’s edge in a tidal cove. His homestead is a compound of multiple buildings and trails, a rope swing, a tree house, and several canoes. Paramount to Bill’s life is his long-term commitment and formal obligation to this place.

Also paramount is a lifelong commitment to independence in thought and action. He once wrote to a friend, “If we become mere followers of the great, we will get a collapsed society and a sterile ecosystem. We cannot afford to invest in followers. If a good society is to emerge on this planet, it will be through the efforts of creative, caring people. Let’s invest all we have in finding and encouraging them. . . .We need not more disciples but more apprentices.”

Discipleship lends itself to emulation or worship, preventing us from seeing through the lives of others into the possibilities for ourselves. The lesson of Bill Coperthwaite’s life is a lesson of experimentation and apprenticeship, of independence of thinking and respect for those who have come before us, of commitment to future generations. “Can we think of this treasure as the fuel for the fire of truth? May we now be reaching the kindling point for the treasure? With creative ability of the minds of people now living, coupled with the wisdom developed over the centuries, we may create a self-sustaining flame of human happiness and growth.”

This book, a richly textured exploration of Bill Coperthwaite’s work and thought, encourages us to take the lessons of his life to heart. Each of us has the potential to craft our own lives with our own hands—actively, joyfully, and nonviolently, drawing upon the wisdom of our ancestors, striving for justice in the present, and fulfilling our obligations to those who will inherit our legacy.

John Saltmarsh is the author of Scott Nearing: The Making of a Homesteader (Chelsea Green, 1998)