THE SHEPHERDESS AND THE CHIMNEY SWEEP

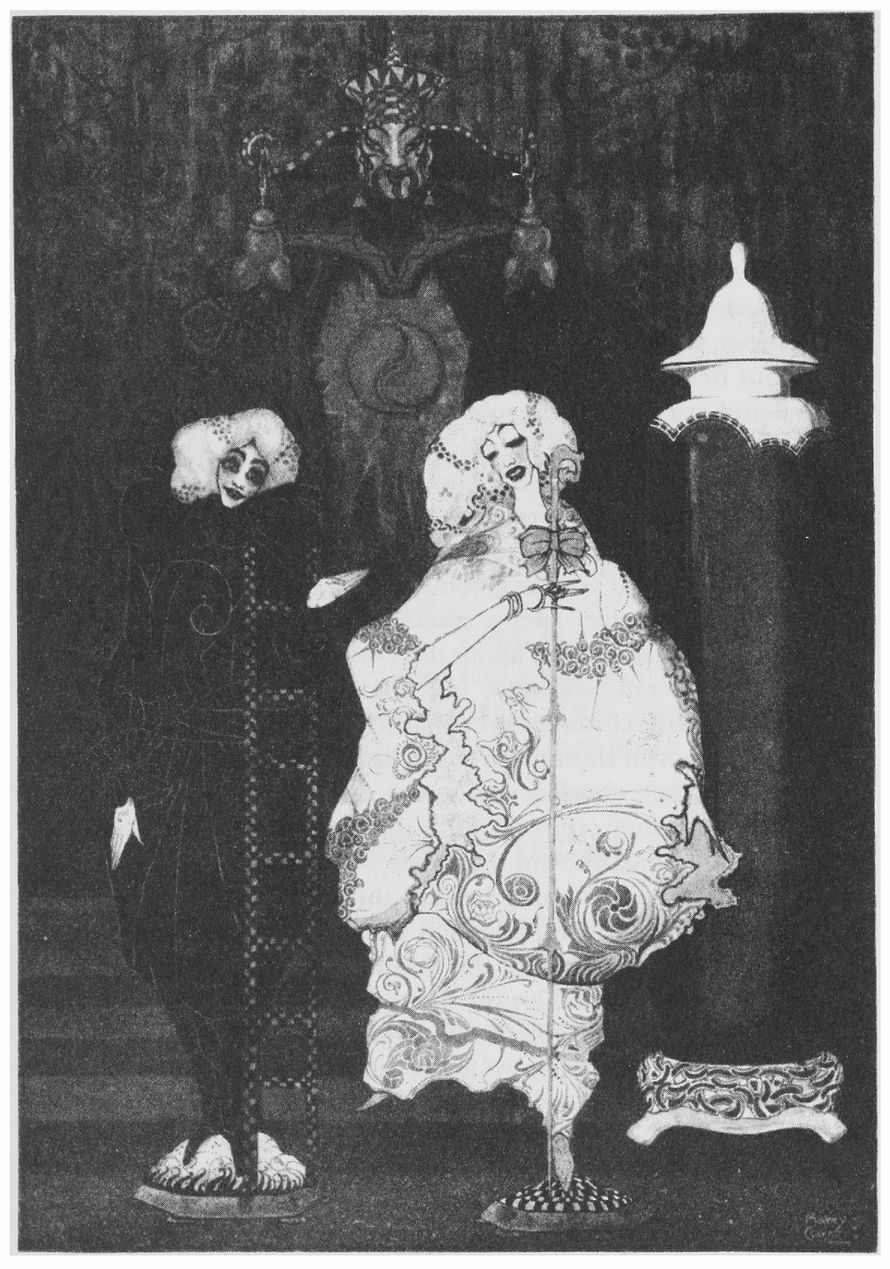

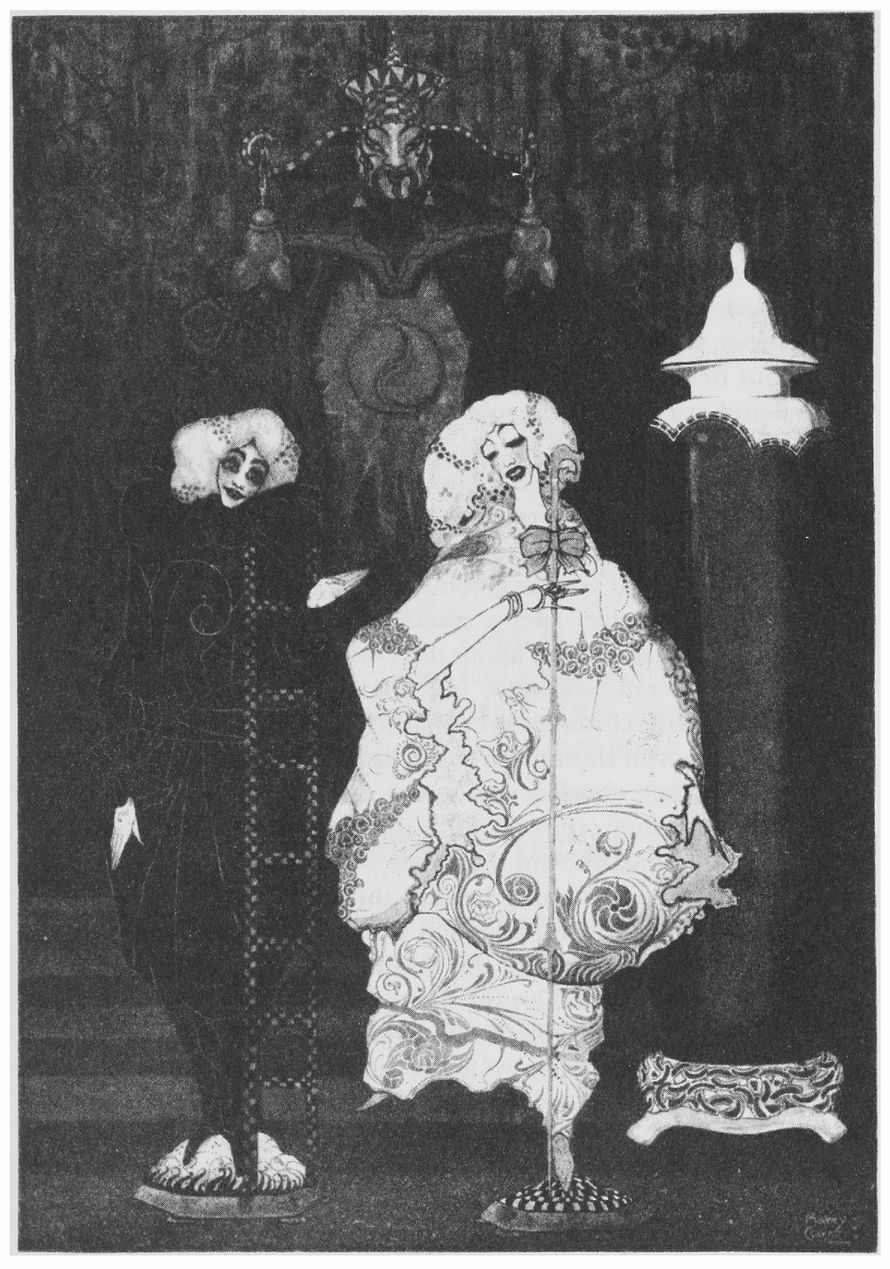

HAVE YOU EVER SEEN a really old wooden cabinet, the kind that’s dark with age and carved with scrolls and leaves? One just like this was standing in the living room. It had been inherited from Great Grandmother and carved with roses and tulips from top to bottom. It had the strangest flourishes, and in between them little stag heads with many antlers stuck out, but in the middle of the cabinet an entire man was carved. He was really funny to look at, and he made a funny face, but you couldn’t call it a laugh. He had goat’s legs, small horns on his forehead, and a long beard. The children in the house called him GeneralBillyGoatlegs-OverandUnderWarSergeantCommander because it was a hard name to say, and not many people have that title. To have carved him must have been hard too, but there he was now! He was always looking at the table under the mirror because there was a lovely little porcelain shepherdess standing there. Her shoes were gilded, and her dress was beautifully held up with a red rose. She had a golden hat and a shepherd’s crook. She was beautiful. Right beside her stood a little chimney sweep, black as coal, but made of porcelain too. He was as clean and attractive as anyone; the fact that he was a chimney sweep was just how he was cast, of course. The porcelain manufacturer could just as easily have cast him as a prince—it wouldn’t have made any difference.

He stood there so nicely with his ladder and with a face as white and red as a girl, and that was actually a mistake because it could have been a little black. He stood quite close to the shepherdess. They had both been positioned where they were, and because of their positions they had gotten engaged. They were well suited for each other: they were young, they were of the same kind of porcelain, and they were both equally fragile.

Close by stood yet another figure who was three times as large. He was an old bobble-head Chinaman. He was also made of porcelain and said that he was the little shepherdess’ grandfather, but although he couldn’t prove it, he insisted that he had power over her, and therefore he had nodded his assent to GeneralBillyGoatlegs-OverandUnderWarSergeantCommander, when the general had proposed to the little shepherdess.

“There’s a husband for you!” said the old Chinaman. “A husband who I think is made of mahogany. He will make you Mrs. GeneralBillyGoatlegs-OverandUnderWarSergeantCommander. He has a whole cabinet full of silver, not to mention what he has hidden away.”

“I don’t want to go into that dark cabinet!” said the little shepherdess. “I’ve heard that he has eleven porcelain wives in there!”

“Then you can be the twelfth!” said the Chinaman. “Tonight, as soon as the old cabinet creaks, there’ll be a wedding, as sure as I’m a Chinaman.” And then he nodded off’ to sleep.

But the little shepherdess cried and looked at her dearest sweetheart, the porcelain chimney sweep.

“I believe I’ll ask you,” she said, “to go with me out into the wide world, for we can’t stay here.”

“I’ll do whatever you want,” said the little chimney sweep. “Let’s go right now. I am sure I can support you by my trade.”

“If only we were safely off the table,” she said. “I won’t be happy until we’re out in the wide world.”

And he consoled her and showed her where to place her little foot in the carved corners and the gilded foliage of the table leg. He used his ladder too, and they made it down to the floor. But when they looked over at the old cabinet, what a commotion they saw! All the carved stags stuck their heads further out, raised their antlers, and twisted their heads. GeneralBillyGoatlegs-OverandUnderWarSergeantCommander leaped into the air and shouted to the old Chinaman, “They’re running away! They’re running away!”

That scared them, and they jumped quickly up into the drawer of the window niche.

Three or four incomplete decks of cards were in there, as well as a little toy theater that was put together as well as possible. There was a play going on, and all the queens—diamonds, hearts, clubs, and spades—sat in the front row and fanned themselves with their tulips. Behind them stood all the jacks and used their heads both at the top and the bottom, the way cards do. The play was about two star crossed lovers, and the shepherdess cried about that, because it was like her own story.

“I can’t stand it!” she said, “I have to get out of this drawer!” But when they reached the floor and looked up at the table, they saw that the old Chinaman had woken up and was rocking his entire body back and forth because his body was one big clump, of course.

“Here comes the old Chinaman!” screamed the little shepherdess, and she fell right down on her porcelain knees; that’s how miserable she was.

“I’ve got an idea,” said the chimney sweep. “Let’s crawl into that big potpourri jar in the corner. We can lie there on the roses and lavender and throw salt in his eyes when he comes.”

“That won’t work,” she said. “Besides I know that the old Chinaman and the potpourri jar were engaged at one time, and there’s always a little goodwill left over when you’ve been in such a relationship. No, we have no choice but to go out into the wide world.”

“Do you really have the courage to go out into the wide world with me?” asked the chimney sweep. “Have you thought about how big it is, and that we can never come back here again?”

“Yes I have,” she said.

And the chimney sweep looked steadily at her, and then he said, “My way goes through the chimney. Do you really have the courage to crawl with me through the stove and through the flue and pipes? We’ll come into the chimney, and I know my way around there! We’ll climb so high that they won’t be able to reach us, and at the very top there’s a hole out to the wide world.”

And he led her over to the door of the wood-burning stove.

“It looks awfully dark in there,” she said, but she went with him, both through the flue and the pipes, where it was pitch black night.

“Now we’re in the chimney,” he said “And look! Look up there—the most beautiful star is shining!”

“Do you really have the courage to go out into the wide world with me?” asked the chimney sweep.

And it was a real star in the sky that shone right down to them, as if it wanted to show them the way. And they crawled and they crept—such a dreadful distance. Up, high up. But he hoisted and helped her and made it easier. He held her and showed her the best places to set her little porcelain feet, and they reached the top of the chimney and sat down on the edge because they were very tired and no wonder.

The sky with all its stars was above them and all the town roofs below. They looked all around, way out into the world. The poor shepherdess had not thought it would be like this. She put her little head on her chimney sweep’s shoulder and cried and cried until the gold washed off her belt.

“It’s just too much!” she said. “I can’t stand it! The world is much too big! I wish I were back on the little table under the mirror. I’ll never be happy until I’m back there again. Now I’ve followed you out into the wide world—you can certainly follow me home again, if you care about me at all!”

And the chimney sweep spoke reasonably to her, talked about old Chinamen and about the GeneralBillyGoatlegs-OverandUnderWarSergeantCommander, but she sobbed so terribly and kissed her little chimney sweep so he couldn’t do other than yield to her, even though he thought it was a mistake.

So then they crawled with great difficulty back down the chimney, and they crept through the damper and the pipe. It wasn’t at all pleasant. And then they were standing in the dark stove. They stood listening behind the door to hear what was happening in the living room. It was completely quiet. They peeked out—Oh! There in the middle of the floor lay the old Chinaman. He had fallen off the table when he had tried to chase them. He was broken into three pieces. His whole back had fallen off in one clump, while his head had rolled into a comer. GeneralBillyGoatlegs-OverandUnderWarSergeantCommander was standing where he always did, thinking things over.

“This is terrible!” said the little shepherdess. “Old grandfather is broken to pieces, and it’s our fault! I’ll never survive this!” and she wrung her tiny little hands.

“He can be mended,” said the chimney sweep. “He can certainly be mended. Don’t get so excited! After they glue his back and give him a good rivet in his neck, he’ll be as good as new and as unpleasant to us as ever.”

“Do you think so?” she said, and then they crept up on the table again where they had stood before.

“So that’s as far as we got,” said the chimney sweep. “We could have saved ourselves all that trouble!”

“If only old grandfather were mended!” said the shepherdess. “Will it be very expensive?”

And he was mended. The family had his back glued, and he got a good rivet in his neck. He was as good as new, but he couldn’t nod any longer.

“You have gotten stuck-up since you were smashed,” said GeneralBillyGoatlegs-OverandUnderWarSergeantCommander. “But I don’t think that is anything to be so proud of. Shall I have her or not?”

And the chimney sweep and the little shepherdess looked so pleadingly at the old Chinaman. They were so afraid he was going to nod, but he couldn’t, and it was unpleasant for him to tell a stranger that he always had a rivet in his neck. So the porcelain couple remained together. They blessed grandfather’s rivet and loved each other until they broke apart.