CHAPTER THREE

SITUATIONAL LEADERSHIP AND EXECUTIVE COACHING

Executive coaching requires exceptional leadership and questioning skills to be effective. At no point is leadership more important than in assisting clients in defining their performance issues and identifying the underlying causes.

In this chapter, we will show how Situational Leadership® provides the needed structure to guide executive coaches in working with their clients. We will add an Executive Coaching Guide© to further elaborate on the process. A model for gap and cause analysis will then be added, followed by sample questions that can be used to assist executive coaches as they guide their clients as they work together to improve organizational performance.

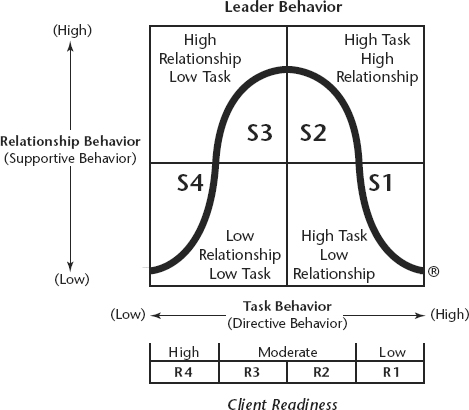

Situational Leadership gives executive coaches the guidance they need as they work with their clients. The underlying principle in Situational Leadership is that executive coaches should adjust their leadership styles to their client’s readiness level (ability and willingness) to perform a given task. Leadership is the amount of task behavior (direction) and relationship behavior (support) given by a leader. (See Figure 3.1.)

FIGURE 3.1. SITUATIONAL LEADERSHIP

Source: Copyright © 1985 by Center for Leadership Studies. All rights reserved.

To be effective, executive coaches must adjust the way in which they lead their clients based on their level of readiness for each task that they are expected to perform. Executive coaching is a unique application of the principles of Situational Leadership that guides executive coaches as they work with their clients.

The lowest readiness level (R1) for an individual or group is described as not willing and not able to do a given task. The appropriate leadership style (S1) is that of providing high amounts of task behavior (direction) and low amounts of relationship behavior (support). The next readiness level (R2) is described as willing but not able. The appropriate leadership style (S2) is that of high amounts of both task and relationship behavior.

The next readiness level (R3) is described as able but unwilling in that the individual lacks confidence or commitment. The appropriate leadership style (S3) is that of high amounts of relationship behavior and low amounts of task behavior. The highest readiness level for a group or individual to do a given task is willing and able (R4). The appropriate leadership style is that of low amounts of both relationship and task behavior.

The Situational Leadership model provides a framework from which to diagnose different situations and prescribes which leadership style will have the highest probability of success in a particular situation. Use of the model will make executive coaches more effective in that it illustrates the connection between their choice of leadership styles and the readiness of their clients. As such, Situational Leadership is a powerful tool for executive coaches to use in working with their clients.

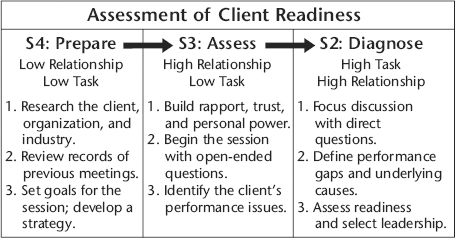

The Executive Coaching Guide is a performance aid that describes a process that is used in formal interviewing, counseling, and coaching situations. The guide is divided into two phases that focus on assessing the client’s readiness and then choosing an appropriate leadership style. The first phase uses Situational Leadership Styles 4, 3, and 2 to prepare, open the lines of communication, and diagnose the client’s readiness level for the tasks necessary to be successful.

When the executive coach is not working with the client, the client perceives a Style 4. The client continues to perceive low amounts of direction and support as the executive coach prepares for the coaching session by reviewing relevant materials, such as records from their previous meeting and setting goals for the session.

At the beginning of the meeting, the executive coach moves to a Style 3, increasing support by building rapport, by opening up the lines of communication, and by reinforcing positive performance or potential. In this step the executive coach works to assess how the client sees the overall situation by asking open-ended questions.

The executive coach then moves to Style 2 to focus the discussion with direct questions to gain further insight into the client’s current problem areas. For each task that is critical for the client’s success, the executive coach must assist the client in defining performance gaps and identifying underlying causes. The executive coach must also assess the client’s readiness (ability and willingness) level for dealing with each performance issue so that the coach can choose the best style with which to intervene.

The assessment phase is described in Figure 3.2.

FIGURE 3.2. ASSESSMENT PHASE

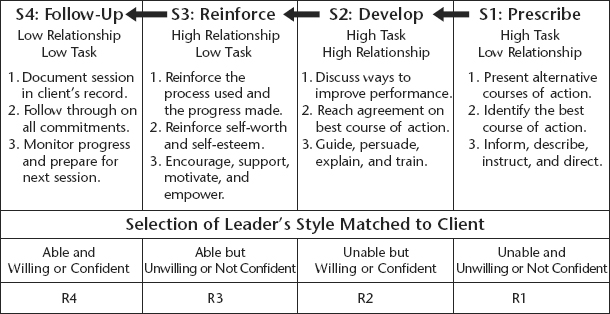

After assessing the client’s readiness for each issue, the executive coach selects the appropriate leadership style based on the client’s readiness level for each performance issue from the diagram in Figure 3.3. As is the case with the Situational Leadership Model, the performance issue must be clearly defined before a readiness level can be determined.

FIGURE 3.3. HIGH PROBABILITY INTERVENTION

Clients can be at several different task-relevant readiness levels for the different issues. Once the readiness level is decided, the corresponding high probability leadership style is chosen to begin the intervention. After the initial intervention, if the client responds appropriately, the executive coach then moves to the next style to further develop the client. The selection of the high probability intervention style is shown in the diagram that follows.

If the client is unable and unwilling or insecure (R1), initially use a Style 1 (Prescribe) to inform, describe, instruct, and direct. If the client is unable but willing or confident (R2), initially use a Style 2 (Develop) to explain, persuade, guide, and train. If the client is able but unwilling or insecure, initially use a Style 3 (Reinforce) to encourage support, motivate, and empower. After making the initial intervention, move through the remaining styles to Style 4 (Follow-Up) to monitor progress and prepare for the next session.

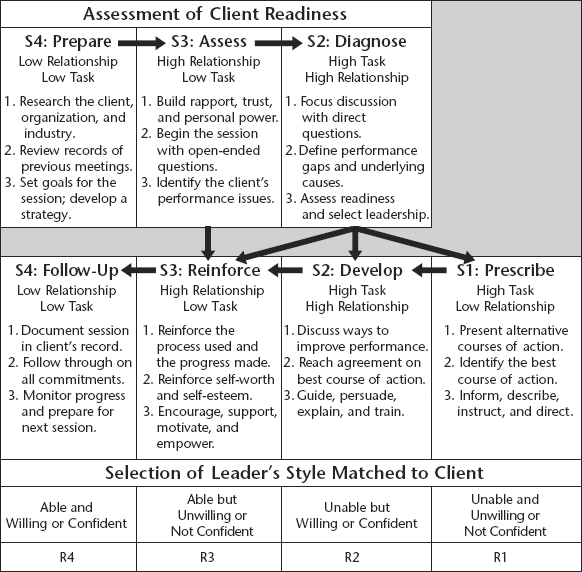

The Executive Coaching Guide in Figure 3.4 is a performance aid derived from the Situational Leadership Model and describes the process used to develop people. The executive coaching process follows a pattern that typically includes varying the amount of direction and support given clients as the executive coach prepares, assesses, diagnoses, prescribes, develops, reinforces, and follows up.

FIGURE 3.4. EXECUTIVE COACHING GUIDE

Copyright © 2004 by Roger D. Chevalier, Ph.D. All rights reserved.

The assessment phase is critical to the coaching process in that the executive coach must prepare, assess, and diagnose prior to making the actual intervention. In effect, the executive coach must “earn the right” to intervene. All too often executive coaches intervene without taking the time to truly assess the client’s readiness. While the initial intervention style is chosen based on the client’s readiness for a given task, the goal is to develop the client by using successive leadership styles as the executive coach moves from prescribe to develop, to reinforce, and then to follow-up.

Performance Gap and Cause Analysis

The key to the executive coaching process is in asking the right questions in the right order to assist clients in identifying their overall situation, specific performance gaps, and the underlying causes. The executive coaching process is an application of leadership in which the consultant becomes a trusted resource for the client.

The starting point in assisting clients in analyzing performance shortfalls is called gap analysis. The executive coach must lead the client in identifying an individual’s or group’s present level of performance (where they are) and their desired level of performance (where they’d like to be). The difference between where they are and where they want to be is the performance gap. Another useful step is to identify a reasonable goal, something that can be accomplished in a short time that moves the organization in the direction toward where it wants to be. This should be defined clearly with measures of quality, quantity, time, and cost delineated for the goal.

Once the performance gap has been defined, the next step is to identify the causes. The Behavior Engineering Model (BEM), developed by Thomas Gilbert and presented in his landmark book, Human Competence: Engineering Worthy Performance,1 provided a way to systematically and systemically identify barriers to individual and organizational performance. This model has been recently updated to better assist executive coaches in assisting their clients in identifying causes for performance gaps.2

The updated model (Figure 3.5) focuses attention on the distinction between environmental and individual factors that have an impact on performance. Environmental factors are the starting point for analysis because they pose the greatest barriers to exemplary performance. When the environmental supports are strong, individuals are better able to do what is expected of them.

FIGURE 3.5. UPDATED BEHAVIOR ENGINEERING MODEL

The support given by the work environment is divided into three factors that influence performance: information, resources, and incentives. Information includes communicating clear expectations, providing the necessary guides to do the work, and giving timely, behaviorally specific feedback. Resources include ensuring that the proper materials, tools, time, and processes are present to accomplish the task. Incentives ensure that the appropriate financial and nonfinancial incentives are present to encourage performance. These apply to the worker, the work, and the workplace.

What the individuals bring to the job include their motives, capacity, knowledge, and skills. Individual motives should be aligned with the work environment so that employees have a desire to work and excel. Capacity refers to whether the worker is able to learn and do what is necessary to be successful on the job. The final factor refers to whether the individual has the necessary knowledge and skills to do a specific task needed to accomplish a project or goal.

The model gives the structure needed to assess each of the six factors: information, resources, incentives, motives, capacity, and knowledge and skills that affect individual and group performance on the job. These factors should be reviewed in this order since the environmental factors are easier to improve and have a greater impact on individual and group performance. It would also be difficult to assess whether the individual had the right motives, capacity, and knowledge and skills to do the job if the environmental factors of information, resources, and incentives are not sufficiently present.

The executive coach can lead the client with questions to identify the causes of performance shortfalls. Thomas Gilbert published a collection of questions used to assess the state of the six cells in his Behavior Engineering Model. He called these questions The PROBE Model, a contraction of “PROfiling Behavior.”3 The PROBE model consisted of forty-two questions to be used to assess the accomplishment of any job in any work situation.

Following Gilbert’s lead, updated PROBE questions were developed to support the Updated Behavior Engineering Model. In addition to the direct questions that reflect the original PROBE questions, open-ended questions have been added to start the discussion with the client. It is important to start the discussion with an open-ended question so as to keep the client from getting defensive from a series of direct questions.

Updated PROBE Questions

A. Information

Open-ended, exploratory question: How are performance expectations communicated to employees?

Direct, follow-up questions:

Have clear performance expectations been communicated to employees?

Do employees understand the various aspects of their roles and the priorities for doing them?

Are there clear and relevant performance aids to guide the employees?

Are employees given sufficient, timely, behaviorally specific feedback regarding their performance?

Does the performance management system assist the supervisor in describing expectations for both activities and results for the employee?

B. Resources

Open-ended, exploratory question: What do your employees need in order to perform successfully?

Direct, follow-up questions:

Do employees have the materials needed to do their jobs?

Do employees have the equipment to do their jobs?

Do employees have the time they need to do their jobs?

Are the processes and procedures defined in such a way as to enhance employee performance?

Is the work environment safe, clean, organized, and conducive to excellent performance?

C. Incentives

Open-ended, exploratory question: How are employees rewarded for successful performance?

Direct, follow-up questions:

1. Are there sufficient financial incentives present to encourage excellent performance?

2. Are there sufficient nonfinancial incentives present to encourage excellent performance?

3. Do measurement and reporting systems track appropriate activities and results?

4. Are jobs enriched to allow for fulfillment of higher-level needs?

5. Are there opportunities for career development?

D. Motives

Open-ended, exploratory question: How do your employees respond to the performance incentives you have in place?

Direct, follow-up questions:

1. Are the motives of the employees aligned with the incentives in the environment?

2. Do employees desire to do the job to the best of their abilities?

3. Are employees recruited and selected to match the realities of the work environment?

4. Do employees view the work environment as positive?

5. Are there any rewards that reinforce poor performance or negative consequences for good performance?

E. Capacity

Open-ended, exploratory question: How are employees selected for their jobs?

Direct, follow-up questions:

1. Do the employees have the necessary strength to do the job?

2. Do the employees have the necessary dexterity to do the job?

3. Do employees have the ability to learn what is expected for them to do to be successful on the job?

4. Are employees free from any emotional limitations that impede performance?

5. Are employees recruited, selected, and matched to the realities of the work situation?

F. Knowledge and skills

Open-ended, exploratory question: How do employees learn what they need to be successful on the job?

Direct, follow-up questions:

1. Do the employees have the necessary knowledge to be successful at their jobs?

2. Do the employees have the needed skills to be successful at their jobs?

3. Do the employees have the needed experience to be successful at their jobs?

4. Do employees have a systematic training program to enhance their knowledge and skills?

5. Do employees understand how their roles affect organizational performance?

Situational Leadership is a powerful tool for guiding executive coaches in interacting with their clients. The Executive Coaching Guide was derived from the Situational Leadership Model and adds more structure to the leadership process. As the key interaction between executive coaches and their clients is to identify performance shortfalls and their causes, the Updated Behavior Engineering Model provides the basis for identifying causes by using the Updated PROBE Questions. This group of performance aid provides the needed structure for the executive coaching process.

Paul Hersey is chairman of the Center for Leadership Studies, Inc., providers of leadership, coaching, sales, and customer service training. He is one of the creators of Situational Leadership®, the performance tool of over ten million managers worldwide and has personally presented Situational Leadership in 117 countries, influencing the leadership skills of four million managers in over a thousand organizations worldwide. He is the coauthor of the most successful organizational behavior textbook of all time, Management of Organizational Behavior, now in its seventh edition, with over one million copies in print. Contact: www.situational.com; ron.campbell@situational.com.

Roger Chevalier, CPT is the author of the 2008 ISPI Award of Excellence recipient, A Manager’s Guide to Improving Workplace Performance, published by the American Management Association (AMACOM Books, 2007). He is an independent consultant who specializes in imbedding training into comprehensive performance improvement solutions. He has personally trained more than 30,000 managers, supervisors, and sales people in performance improvement, leadership, coaching, change management, and sales programs in hundreds of workshops. Contact: www.aboutiwp.com.

Notes

1. T. F. Gilbert, Human Competence: Engineering Worthy Performance (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978).

2. R. D. Chevalier, “Updating the Behavior Engineering Model,” Performance Improvement 42 no. 5 (2003): 8–14.

3. P. J. Dean (Ed.), Performance Engineering at Work, 2nd ed. (Silver Spring, MD: International Society for Performance Improvement, 1999).