CHAPTER FIVE

DEMYSTIFYING THE COACHING MYSTIQUE

Any good leader wants to get better. To improve, leaders have attended seminars, read books, shadowed colleagues, received formal (and informal) feedback, and taken on new assignments. In recent years, coaching has been the rage. So much so that it has almost become all things to all people. Coaches have ranged from being trained professionals to executives between jobs. As coaching broadens both in content (what is being coached) and process (who is doing the coaching), it becomes more difficult to help executives improve through coaching. In the complex landscape of coaching, executives have a more difficult time answering the questions: What can I expect from my coaching experience? Who do I turn to as my coach?

We want to answer both questions by starting with a simple typology of what they can expect from coaching and then discuss five coach archetypes that executives can select for coaching.

What Can I Expect from My Coaching Experience?

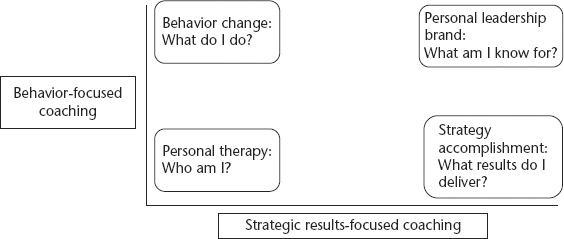

We suggest that there are two general coaching foci: behavior change and strategy realization (see Figure 5.1).1 Behavior change means that the executive being coached has behavioral predispositions that get in the way of being an effective executive. Strategy realization means that the executive being coached needs help to clarify and focus the business strategy to help the business achieve financial, customer, or organizational goals. These two dimensions lead to four outcomes of coaching.

FIGURE 5.1. COACHING OUTCOMES

Behavior-Focused Coaching

Changing behavior is not easy. We know from research that about 50 percent of an individual’s values, attitudes, and behaviors come from DNA and heritage; the other 50 percent are learned over time.2 This split means that while we each have predispositions, we can also learn new behaviors. We also know that about 90 percent of how we behave comes from habits (either from our heritage or learned over time) and that these habits are very difficult to change.3 When working to help leaders change behaviors, it is helpful for them to recognize their predispositions, but understand that they are not bound by them. When specific behaviors are identified, examined, and modified, coaches help executives change. The past sets conditions on our behavior, but our behavior is not preconditioned.

Strategic Results–Focused Coaching

Strategic results coaching focuses more on helping the executive gain clarity about the results he or she hopes to accomplish and how to make them happen. It is less psychological and more organizational. Strategy coaching starts with clarity about desired goals, then reviews how the coachee can spend time with key people and accomplish tasks to reach those goals.

Personal Leader Brand Coaching

Every leader has an identity, a reputation, or what we call a leader brand.4 The leader brand is a combination of both behavior and results. Behavioral coaching helps a leader recognize and develop his or her style and results coaching helps the leader focus on and deliver desired results. The combination of the two results is a personal leader brand. A personal leader brand is an individual’s identity, reputation, or distinctiveness as a leader; it identifies strengths and predispositions and includes provisions to mitigate the effects of weaknesses. This personal identity becomes a reputation that others respond to and reinforce. Mature executives realize that over time people will tend to forget some of the things leaders do (initiatives completed, speeches given, goals set and accomplished), but they will remember the combination of these acts and the personal style that leaders demonstrate.

Therapy-Focused Coaching

Often, coaching scratches the surface of deeper psychological and emotional issues. Professionally trained therapists will, at times, moonlight (or even masquerade) as coaches to avoid the apparent executive stigma against seeking out professional psychotherapy. At times, coaches open emotional wounds that require more intense therapeutic work. Historical relationships with parents, emotional trauma, and early childhood experiences may cause leaders to act in ways they don’t fully understand. In these cases, coaches who either are, or refer to, trained therapists can help redefine cognitive patterns.

Executives who enter into coaching should be clear about what they hope to gain from the coaching experience. Are they interested in behavior change? Strategic results? A personal leader brand? Psychological discovery and healing? Each outcome requires different levels and types of executive commitment. And each can be facilitated by selecting the right coach.

To Whom Can I Turn for My Coaching?

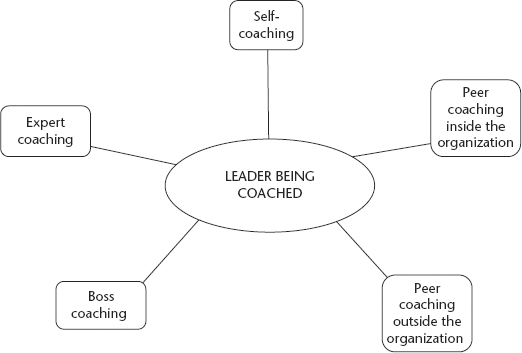

We have identified five coaching archetypes. Each coach archetype represents an individual or type of individual where a leader can turn for coaching (see Figure 5.2):

FIGURE 5.2. COACHING ARCHETYPES

1. Self-coaching. By being self-aware, leaders can change their behaviors and improve their performance.

2. Peer coaching inside the organization. Leaders can find allies or friends inside their organization who can advise and guide them.

3. Peer coaching outside the organization. Leaders may join social networks of like-minded professionals outside their organization to help them.

4. Boss coaching. A leader’s direct supervisor may coach behavior and results change.

5. Expert coaching. A leader may turn to an expert coach who has credentials and experience to inform behavior and improve results.

We find this typology enormously helpful when we advise leaders on how to become better by selecting the coach type that works best for them. Each coaching archetype has strengths and weaknesses and may be more or less able to accomplish one of the four outcomes of coaching. These coaching types are not mutually exclusive, but can work in tandem to achieve desired outcomes.

1. Self-Coaching

In some ways, we know ourselves better than anyone else and can employ the most effective form of incentive—internal motivation. Self-coaching occurs when we self-monitor and recognize how our intentions are not aligned with our actions. At some level, self-coaching is the most ideal and efficient. If and when leaders recognize their predispositions and act on them, they are more likely to make change stick. Dave knows, for example, that he is predisposed to being an introvert. So when he teaches or gives talks, he knows he has to overcome this tendency and engage the group in conversation. Jessica knows she mentally sets expectations for herself and others. She’s learned through reflection that if she doesn’t recognize and communicate those expectations, others have an impossible time meeting them.

Leaders who self-coach need to be very aware of their personal predispositions and how they come across to others. We advise leaders to be mindful and “have their heads on a swivel” to see how others are responding to them. Self-coaching takes time. Leaders need to carve out space to reflect on what worked and what did not work. Ego should not be invested in what they have done or who they are, and they need to be willing to publicly acknowledge that they are changing. Leaders should solicit and listen to feedback without being defensive and employ self-discipline to change.

One leader we worked with had received some feedback that he had a tendency to let his frustrations out often and it was affecting the morale of his employees. He decided he wanted to work on the issue and examined the triggers that set him off, went public with his employees and talked about those triggers, and asked for their help as he worked to keep his frustrations in check. He now reports a much happier workplace environment and less personal stress.

Self-coaching may be more attuned to delivering results than changing behaviors. Results are more visible and public while behaviors are more private and personal. Self-coaching leaders may be able to dig into why results did or did not occur more easily than figuring out how their behaviors help or hinder a result.

However, self-monitoring is as dangerous as doctors who self-medicate. We often judge ourselves by our intentions and others judge us by our actions. An executive we coached wanted to make sure that the team made the best possible decisions. He often intervened in team decision making—advocating his recommended decision. His intent was to improve decisions, but his team members saw this as intrusive and autocratic. They withdrew and became passive observers. He was not mindful regarding how his intentions were seen by others. Marshall Goldsmith has found that 80 percent of the people rate themselves in the top 20 percent of performance because they are judging their intentions not outcomes.

2. Peer Coaching Inside the Organization

In almost every training program, one of the introductory comments is to turn off all cell phones. We have found remarkable success at the end of a training program when we ask participants to take out their cell phones and to e-mail or text a friend something that they have learned and something that they will do. Most participants send notes to peers inside the organization whom they trust. These peers become coaches, either formally or informally, as they help leaders make change happen.

Leaders who use peer coaching often have a friend at work who cares for them. As a friend, this peer observes the behaviors of the leader and knows his or her intentions. In informal and casual settings, the peer coach can help the leader change behaviors and better deliver results. Leaders who take the personal risk of asking their work allies how they are doing will quickly learn if a friend can also be a coach. Friends who do not give honest feedback—even when asked—may stay friends, but they are not peer coaches. Smart leaders seek out insightful peers who are willing to be coaches. One leader intentionally sought out allies on her team and throughout the organization who would privately let her know how she was doing. These allies were peer coaches and an invaluable source of insight on her leadership style.

Peer coaches need not always be in the same line of business within an organization. We’ve seen much success when leaders from different business units of the same firm get together on a regular basis to discuss areas they’re working to improve, and issues they’re grappling with. The same types of issues arise around the organization, and hearing a different perspective on possible solutions and proven practices can be instructive.

Relying only on peers has limitations as peers may not see the whole picture, nor may they have a deep understanding of the leader’s motives and expectations. Friends as peers may also not be as objective as they could be—not wanting to cross the line between friendship and coaching.

3. Peer Coaching Outside the Organization

Social networking has changed how strangers connect to each other. A fascinating movement exists today where older adults who want to stay in their own homes join a village network organization that connects them to others in similar circumstances. About a hundred of these “villages” exist in the United States and are growing rapidly; in these villages, independent people pay a fee to join, and then serve each other. Former strangers connect with each other:5

- Ferni, 25, an options trader, provides computer coaching to Susan, 73, a retired family nurse.

- Bud, 89, a retired executive, helps Bob, 66, a retired attorney, develop a preschool volunteer program.

- Susan, 32, helps Carole, 68, a retired college administrator, organize her files in her new apartment.

If social networking can help retired individuals learn and grow, it can also help leaders.

We have identified four types of networks where people come together to improve. In each of these networks, leaders can connect with those outside their organization to gain insight and become better:

1. Relationship networks: who we go to when we want to have fun. The Gallup organization has argued that we need to have a best friend at work. We would argue that it is equally if not more important for leaders to have a best friend (outside the family) NOT at work and who does not really tie the relationship to the work setting.

2. Knowledge networks: who we go to when we need information. Leaders can be encouraged to join professional associations, to create cohort groups of peers, and to attend conferences to meet and associate with peers who have ideas to solve problems.

3. Trust networks: who we go to with personal or confidential information. Leaders may find trusted advisors in neighborhoods, religious associations, social groups, longtime friends, or extended family to whom they turn for personal questions and insights.

4. Purpose networks: who we go to when we need to accomplish a task. Leaders may get insights from consultants, advisors, former faculty, or other experts about projects they need to accomplish.

Depending on the network, these peers outside of work offer insights on both behavior and strategic change. There are a lot of tools to help build your network online, but remember that they alone are not your network. Whether online or in person, all networks must be nurtured.

Peers outside the organization may offer candid insights, because they are not in a position to harm the friendship, but they may also lack the emotional sensitivity required for sustained change. The research on relationships suggests we need close friends (called tight ties) who emotionally support us and more casual friends (called loose ties) who give us innovative and fresh approaches to problems. Leaders who invest in relationship, knowledge, trust, and purpose networks develop the loose ties that help them succeed.

4. Boss Coaching

In one organization, the senior executive squashed the coaching budget, because she felt that the leader’s immediate boss was the most important coach and she did not want anything to detract from that relationship. In many ways, she is right. Leaders who coach and communicate rather than command and control have enormous opportunities for impact. In other ways, she is wrong. When we coach individuals, they need to be able to explore a range of issues—some of which may include their relationship with their boss, their future with the company, and other personal issues that will not likely be discussed in boss coaching.

Bosses who coach need to develop not only a mindset but a set of skills to coach. Instead of demanding results, they learn to ask thoughtful questions and listen to understand. We have encouraged bosses who coach to master the questions shown in Table 5.1

TABLE 5.1: COACHING QUESTIONS FOR BOSSES

| Principles of Coaching | Coaching Questions Bosses Should Be Asking |

| Build relationship of trust | How can I be helpful? What would you like from this conversation? Help me understand . . . |

| Describe current performance | What are the results you are after? How well do you think you have done? Why? What led you to this current result? What do you do that helps or hinders reaching your goal? |

| Articulate desired results | What would you like to accomplish? How do you feel about the outcome you are after? How will you know when you have succeeded? |

| Build action plan for change | What are the alternative actions you can take to reach your goal? What are pros and cons of each? What are the first steps you need to take? What can I do to help you be successful? How will you learn from things that don’t go well? To whom will you be accountable for progress? |

Bosses who can ask questions more than give answers, who seek to understand before giving direction, and who work to build trust before taking action can become excellent coaches.

However, bosses as coaches also have limitations. The Lominger group found that of the sixty-seven key skills for business leaders, “coaching” is toward the bottom.6

Many bosses rose to their positions of influence not by coaching but by doing. The derailment that many of them face is that although they are competent, they are not able to multiply that competence in others. Leaders wanting to improve can and should rely on their boss not only for performance reviews, but also for career counseling where the boss can point the leader in a positive direction.

5. Expert Coaching

Expert coaching may take a variety of forms. The expert may be inside the company as a trained coach who can work with someone generally not in the same department or function. The expert may be a licensed psychologist who may help a leader explore some of the more emotional issues underlying his or her behavior. Most often, the coaching expert has training in personal and organization change, has experience with multiple executives in multiple companies, and can tailor and bring to bear their previous experiences to the leader being coached. Coaching certifications, like all certifications, ensure that the coach has basic knowledge, not that the coach can be successful. For example, an attorney, architect, or psychologist who is licensed has certified that they know the basics of their profession, but the license does not mean that they can practice well.

Experts with face validity need to be selected for the individuals being coached. Leaders being coached need to have personal and professional chemistry with the expert, and need to be willing to share personal issues that may be difficult to share with those inside the company. Leaders need to be willing to face reality and commit to making changes.

Expert coaches may help leaders make both behavior and results changes. They may explore candid and, at times, brutal information about the leader’s behavior and performance. They may make suggestions about how to improve and challenge the status quo. They may also help the leader create a personal leadership brand by combining behavior and results into a leadership identity. One senior leader we coached said that he enjoyed our sessions because, “When you come into my office, I am your primary agenda. Everyone else who sees me has an agenda of what they want to get from me, either explicitly or implicitly. Your agenda is giving to me.” Experts give leaders coaching help when their insights turn into actions.

However, expert coaches also have limitations. They do not live inside the organization and see the day-to-day operations. They may be used as sounding boards without real accountability for action. As expert coaches, we have found it most useful to meet with the leader’s HR head before and after the coaching session. The HR head can alert us to current political issues in the organization and on the leader’s mind before the coaching session. After the session, while maintaining confidentiality, the leader’s HR head may ensure that the follow-up is institutionalized and sustained.

Increasingly, coaching is a valued part of leaders wanting to improve. But, when it is nebulous—both in terms of content (what we accomplish) and process (who is the coach)—it is superficial window dressing, not sustainable leadership. We encourage leaders who desire the assistance of a coach to be clear about what they want from the coaching experience and who they want to help them as coaches.

Dave Ulrich is a professor at the Ross School of Business, University of Michigan, and a partner at the RBL Group, a consulting firm focused on helping organizations and leaders deliver value. He studies how organizations build capabilities of leadership, speed, learning, accountability, and talent through leveraging human resources. He has helped generate award-winning databases that assess alignment between strategies, organization capabilities, HR practices, HR competencies, and customer and investor results.

Jessica K. Johnson is a principal consultant at The RBL Group. Prior to joining RBL, Jessica worked with Cisco where she created Cisco’s first global results-based strategy for their external events. Prior to that she worked at the McLean, Virginia–based consulting firm BearingPoint. While there she managed the operations for BearingPoint’s Global Delivery Centers in India and China. She started her consulting career working on a variety of federal client projects.

Notes

1. See Dave Ulrich, “Coaching for Results,” Business Strategy Series 9, no. 3 (2008): 104–114.

2. A review of this work was presented at 21st Annual SIOP (Society of Industrial and Organizational Psychology), Dallas, Texas April 2006, in a paper by Richard Arvey, Maria Rotundo, Wendy Johnson, Zhen Zhang, Matt McGue entitled “Genetic and Environmental Components of Leadership Role Occupancy.” The nature/nurture debate is also dealt with in the following:

Thomas J. Bouchard Jr., David T. Lykken, Matthew Mcgue, Nancy L. Segal, and Auke Tellegen, “Sources of Human Psychological Differences: the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart,” Science Magazine (October 12, 1990).

Judith Rich Harris, The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out The Way They Do (New York: The Free Press, 1998).

Judith Rich Harris, “Where Is the Child’s Environment? A Group Socialization Theory of Development,” Psychological Review 102, no. 3 (July 1995): 458–489.

M. Mcgue, T. J. Bouchard, Jr., W. G. Iacono, and D. T. Lykken, “Behavioral Genetics of Cognitive Ability: A Life-Span Perspective,” in Nature, Nurture, and Psychology, ed. R. Plomin & G. E. Mcclearn (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1993), 59–76.

3. The work on changing habits comes from Joseph Grenny at VitalSmarts who found that 73 percent of executives know they need to change, but don’t. M. J. Ryan in This Year I Will . . .: How to Finally Change a Habit . . . found that 8 percent kept New Year’s resolutions and 90 percent of our lives are daily routines, most of which do not change.

4. The work on personal brand has been discussed by Tom Peters, The Brand You 50: Or Fifty Ways to Transform Yourself from an “Employee” into a Brand That Shouts Distinction, Commitment, and Passion! (New York: Knopf, 1999).

Turning this personal brand into a leadership brand can be found in Dave Ulrich and Norm Smallwood, Leadership Brand; Developing Customer Focused Leaders to Drive Performance and Build Lasting Value (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Press, 2007).

5. An overview of the social network village for retired individuals can be found in: Martha Thomas, “The Real Social Network,” AARP (American Associate of Retired Persons), The Magazine (April 2011).

6. Michael M. Lombardo and Robert W. Eichinger, FYI: For Your Improvement, A Guide for Development and Coaching, 4th ed. (Minneapolis: Lominger, 2004).